Abstract

This paper aims at reviewing autistic children’s lived educational experience to inform ongoing legal and conceptual debates about their right to education. The results showed that autistic children display a great diversity of educational needs and preferences, which should be met with personalized solutions respectful of their individual and collective identity. Mainstream inclusion, while sometimes positive, also appeared at times to hinder the delivery of a quality and inclusive education, if nothing else due to sensory issues and overwhelming anxiety. This underlines the necessity to adopt a more neurodiverse interpretation of the notions of quality and inclusive education, in order to preserve and develop diverse and proper educational offers for each and every autistic child.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The particular importance that education carries for autistic children is commonly underlined by the literature (Cera, 2015). However, and despite an extensive legal protection, autistic children continue to suffer from poor educational experience and outcomes (Bottroff et al., 2019; Roberts & Simpson, 2016). This paper contends that, in addition to various problems at the implementation level, this situation stems from conceptual issues in the legal interpretation of their right to education. While some literature has started to acknowledge and address these issues (Ashby, 2010; Barua et al., 2019; Freeman, 2020), this has so far been done without much consideration for autistic children’s inputs. This paper therefore intends to review available inputs from autistic children to inform the discussion on the conceptual and legal issues related to their right to education.

Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by differences in sensory processing, cognitive functioning, communication, and social interactions (American Psychological Association, 2013; Runswick-Cole et al., 2016; World Health Organization, 2019). While acknowledging that there is no consensus on the preferred terminology (Lorcan et al., 2016), this paper uses the term “autism” as encompassing all shades of the autism spectrum and adopts an identity-first language. This paper also subscribes to the neurodiversity theory, which considers autism as a different, non-pathological, neurological functioning (Jaarsma & Welin, 2012). Such difference in neurological functioning is also compared by some authors to those of gender or race (Huijg, 2020; Singer, 2017). Autism can therefore be conceived both as a disability and a type of minority, in opposition to a neurotypical majority (Chown, 2020; Milton, 2017). As such, the neurodiversity theory allows to challenge neurocentric assumptions and to provide neurodiverse interpretations (Bertilsdotter-Rosqvist et al., 2020), which appears especially needed regarding the conceptualization of autistic children’s right to education.

Within the international and European context, autistic children’s right to education is provided for by several treaties, and in particular the First Protocol to the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental FreedomsFootnote 1 (Council of Europe, 1952); the Convention on the Rights of the ChildFootnote 2 ([CRC] UN, 1989); and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with DisabilitiesFootnote 3 ([CRPD] UN, 2006). Taken together, these dispositions provide autistic children with a right to availability and access to quality and inclusive education (Reyes, 2019). These four components are briefly detailed below.

Availability and access require states to render education—at the very least a free and compulsory primary education—available and accessible to all children. Rendering education available involves providing for infrastructures, teaching materials, and teachers (de Beco, 2014; Tomasevski, 2006), for example, through free public schools or through subsidized private schools. Accessibility then entails guaranteeing access to this national educational offer without discrimination, including based on children’s disability (Courtis & Tobin, 2019; Lile, 2021).

Quality education—which is close to the concept of free and appropriate public education (FAPE) used in American law (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act [IDEA], 2004)—requires that the education provided be effective and appropriate. According to international law, it should then foster the aims of education, as prescribed in the CRC (Article 29 §1) or the CRPD (Article 24 §1). While there exist many categories of the aims of education, two of them appear to be of specific relevance for autistic children: the individual aims and the identity aims. Briefly described, the individual aims focus on the development of the child’s personality, self-esteem, and skills (Lile, 2021), while the identity aims provide for the protection of the identity, culture, and values of the child—as well as those of their parents and their country (CRC Committee, 2001, §4; Lile, 2021).

Inclusive education is mainly provided for by Article 24 of the CRPD, which requires that the right to education of disabled persons be realized “without discrimination and on the basis of equal opportunity [through] an inclusive education system at all levels” (§1). To allow this realization, the article provides for two legal mechanisms, namely support measures—which are systemic, non-individualized, and of progressive realization—and reasonable accommodations—which are individualized and of immediate application (Cera, 2015). Inclusive education is close to the concept of the least restrictive environment (LRE) found in American law (IDEA Act, 2004). However, it has so far been legally interpreted by the CRPD Committee—in charge of monitoring the implementation of the CRPD—as full mainstream inclusion only (CRPD Committee, 2016a, §40).

The international right to education of autistic children has been largely transposed in the national laws of European countries, either as part of their general disability legislation (e.g., the British Special Educational Needs and Disability Act [2001]) and/or autism-specific policies (e.g., the French 4th Autism Plan [Gouvernement de la République française, 2018]). Depending on each national system, the education of autistic children can take different forms and the choice regarding which school to attend or which education to receive can be restricted (e.g., due to availability, restrictions on home-schooling, or compulsory geographical allocation). To give some illustrations, autistic children can be educated: either mostly in mainstream schools and classrooms (e.g., in Italy); or mostly in special schools, which can be autism-specific or not (e.g., in Switzerland or Flemish Belgium); or in either special or mainstream schools, sometimes with mixed options such as satellite classrooms or resources provisions attached to a mainstream school (e.g., in Finland, Denmark or the UK).

Despite this formal recognition and protection of their right to education, the educational outcomes and experience of autistic children remains poor, even when compared to other disabled populations (Bottroff et al., 2019; Roberts & Simpson, 2016). In addition to difficulties at the implementation level (Barua et al., 2019; Jordan, 2008; Marshall & Goodall, 2015), this paper contends that conceptual issues regarding autistic children’s right to education are also at play. The central problem is that the right to education has so far been interpreted through a neurocentric approach, which then reduces its relevance for neurodivergent populations, such as autistic children. Providing a neurodiverse interpretation of the right to education appears then necessary, starting with a reconceptualization of the notions of quality and inclusive education.

Regarding quality education, there have been few attempts to understand what a neurodiverse conceptualization of the individual and the identity aims of education would entail for the development of autistic children’s skills, self-esteem, personality, and individual or collective identity. Autistic children often need to learn what is otherwise obvious to others (Jordan, 2019), while sometimes exhibiting above average abilities, including in academic subjects such as mathematics or literacy (Clark, 2019). In addition, while the questions of identity and diversity in education have so far mainly concerned religious, linguistic, or ethnic communities, the growing acknowledgement of an autistic identity and culture (Bertilsdotter-Rosqvist et al., 2020; Kapp, 2020; Silberman & Sacks, 2016) could increase their relevance to autistic children. How to provide autistic children with an education that respects their neurodiversity while equipping them with all the skills needed to be included in society remains an ongoing discussion, both at the educational and legal level.

Similarly, regarding inclusive education, debates have been going on between the full inclusionists and the moderate inclusionists. The former, which includes the CRPD Committee, defend the inclusion of all disabled children within mainstream schools and classrooms only, while the latter advocate for a continuum of diverse schooling options, including special schools (Boyle & Anderson, 2021; Goodall, 2021; Hyatt & Hornby, 2017). However, few studies have considered the conceptualization of inclusive education by autistic children themselves. One notable exception is found in Lüddeckens (2021) systematic review on the conception of inclusion by autistic adolescents. This review highlighted a rather different conception of inclusion between autistic students and other stakeholders, including teachers and parents. This emphasizes the need to incorporate autistic children’s lived experience and voices in the legal and conceptual debates on their right to education.

Indeed, while the topic of autism and the autistic population have been widely researched over the past decades, scholars have pointed out the lack of involvement of autistic people in studies conducted about them (Chown et al., 2017). Research on autism and education has for example been predominantly carried out with teachers or parents rather than children (Goodall, 2021; Roberts & Simpson, 2016). To better understand the school experience of autistic children has however been identified as a priority for research by the autistic community (Pellicano et al., 2014, 2018). Researching autistic children’s educational experience also appears essential to inform professionals’ theories (Zuber & Webber, 2019) and to ensure that debates and decisions are not only guided by ideology (Goodall, 2021). To respond to this need, a growing body of literature on autistic children’s educational experience has started to emerge (e.g., Baric et al, 2016; Goodall, 2021; Howe & Stagg, 2016). However, these studies mostly stem from social sciences or educational sciences, and few if not none have been conducted with a legal approach. Similarly, some literature reviews have been published around autistic children’s educational lived experience, for example, focusing on their well-being (Danker et al., 2016), self-identity (Williams et al., 2019), perception of inclusion (Lüddeckens, 2021; Roberts & Simpson, 2016), or transition (Stack et al., 2021). However, to the author’s knowledge, there has not been any attempt at reviewing these accounts through a legal lens. Conversely, while the conceptualization of the right to education, including related to disability or neurodiversity, has started to attract more attention from legal science (Anastasiou et al., 2018; Arduin, 2019; de Beco, 2019; Kanter, 2019; Lollini, 2018), these discussions have so far rarely included inputs from autistic children.

Therefore, this paper aims at reviewing autistic children’s lived educational experience to inform ongoing legal and conceptual debates around their right to education. More specifically, it will address the following research questions:

-

1.

What are the main features of the educational lived experience of autistic children?

-

2.

How does the educational lived experience of autistic children inform the legal and conceptual discussions on a neurodiverse interpretation of quality education?

-

3.

How does the educational lived experience of autistic children inform the legal and conceptual discussions on a neurodiverse interpretation of inclusive education?

Question 1 will be researched through a literature review of empirical studies on the educational experience of autistic children. The results of this literature review will then be used to address questions 2 and 3 through the Discussion section.

Methods

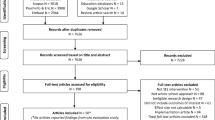

The literature review was conducted under the form of a rapid review. Rapid reviews follow the process of a systematic review but allow for the exclusion of some of its components to accommodate time or resource constraints (Tricco et al., 2015). Accordingly, the present review was conducted in a shorter timeframe, and most stages were carried out by one researcher only. However, the rapid review was systematized and followed the guidelines and recommendations for systematic reviews to the fullest of what the attached constraints permitted. A review protocol was designed during a methodological workshop between the author and senior researchers from legal and social sciences, and implemented with the support of a professional librarian. The review followed the ENTREQ guideline for enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research (Tong et al., 2012), and a PRISMA flowchart (Page et al., 2021) reporting the results of the search and selection process is provided in Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram (Page et al., 2021) detailing the search and selection process applied during the review

Search and Selection Process

The search was first carried out in the following online databases: Web of science; ERIC (EBSCO); Medline (Ovid); and APA PsychINFO (Ovid). These databases were chosen because they offered a coverage of both the generalist and specialist literature relevant to the topic.

As shown in Table 1, the database search used a combination of keywords based on the population, context, and outcome (PCO) items of the research topic.

To enhance their reliability, the keywords were checked against official autism classifications—namely the International Classification of Diseases ([11th revision] World Health Organization, 2019) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders ([5th edition] American Psychological Association, 2013)—against the keywords used in other relevant systematic literature reviews with similar PCO components, and against the keywords of already identified relevant publications. In databases offering this possibility, the search was limited to qualitative publications. In other databases, relevant additional keywords on study design were added in the search. Thesaurus and/or free text search as well as Boolean operators and individual database search features were used to optimize the search results.

In addition to databases search, an ancestry citation search and a forward citation search of the included studies were also conducted. These methods have been found to substantially increase the recovery of relevant literature (Wilson et al., 2020). An online hand-search of the following journals, offering a specific focus on autism studies, was also carried out: Autism; Research on Autism Spectrum Disorder; Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders; Good Autism Practice; Autonomy; Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities; Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities.

The search was limited to English- and French-language academic articles, focusing on European countries, and published from 2009 onwards. The timeframe was chosen because of the date of entry into force of the CRPD—on the 8th of May—and the geographic focus corresponds to the scope of the PhD thesis this paper is part of. In addition, to be included, the publications resulting from the searches had to meet certain inclusion criteria, as shown in Table 2.

According to these criteria, the search results were first submitted to an initial screening of titles and/or abstracts (stage 1.1). Due to the amount and characteristics of the initial results, an intermediary screening stage consisting in a rapid scanning of the pre-selected publications’ text was carried out (stage 1.2). These screenings were conducted by the author only. They were followed by a screening of the full text of the pre-selected publications (stage 2). For this last stage, a second reviewerFootnote 4 performed an independent screening of more than a third of the publications (37.5%), which resulted in no divergence of evaluation. At the end of the screening rounds, 12 publications were found to meet all the inclusion criteria, this number being coherent with other literature reviews on similar topics (e.g., Danker et al., 2016; Stack et al., 2021).

Ensuring the quality of the data retrieved is crucial for a literature review, since these data will form the core of its findings and analysis. To do so, the quality of the included publications was appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative studies checklist. The appraisal was first conducted by the author. To ensure the reliability of the appraisal, more than half of the included studies (58%) were also appraised independently by the second reviewer. No significant divergence was found between the two appraisals, and all the included studies were rated with a good enough quality to be included in the review.

Included Studies Characteristics

Following their appraisal, relevant data were extracted from the included studies. A summary of these can be found in Table 3.

Together, the included studies represented 83 participants, with a male/female ratio of approximately 4:1, which reflects the sex ratio that predominated in autism diagnosis until recently (the actual ratio being closer to 3:1 [Loomes et al., 2017]). Although this information was not systematically expressly available, it appears that most participants were studying at the secondary level (at least 55 of them). Similarly, while not systematically stated, it can be gathered from the methods used that most of the participants were speaking or semi-speaking. Most of the included studies were carried out in the UK. This can be partly explained by the language inclusion criteria, and by the prevalence of Western English-speaking countries traditionally found in autism research (e.g., Bailey & Baker, 2020; DePape & Lindsay, 2016; Zuber & Webber, 2019). It is to be noted that four of the included studies were based on the same fieldwork and therefore reported on common participants (Goodall, 2018b, 2019, 2020; Goodall and MacKenzie, 2019). The four studies were nonetheless kept separate because they presented different results and answered different research questions. However, the fact that they shared common participants and fieldwork was dully considered in any numbered or quantitative mentions.

Data Analysis

For each included studies, the text data from the findings or results section were extracted, coded, and synthetized. As prescribed by the literature (Gale et al., 2013; Pope, 2000; Srivastava & Thomson, 2009), the synthesis process was carried out following five main steps, namely: (a) familiarization with the data; (b) finalizing the codes and categories; (c) indexing all the data using the established codes and categories; (d) charting the data into the framework matrix; and (e) mapping and interpretation. An inductive approach, namely descriptive coding (Saldaña, 2009), was employed to design the different codes and categories. These categories were then regrouped under themes using mostly inductive coding (axial and pattern coding [Saldaña, 2009]) combined, when relevant, with a deductive approach based on the legal and conceptual questions previously identified. The synthesis of these results can be found in the next section, followed by the analysis of their relevance to inform the conceptual questions surrounding autistic children’s right to education.

Results

As detailed below, the results revolve around five main themes: socio-emotional and sensory experience; identity and relational experience; learning experience; support and accommodations; and mainstream and special settings. Their occurrence across the included studies is synthetized in Fig. 2.

Socio-Emotional and Sensory Experience

Regarding the socio-emotional and sensory dimensions, the literature review revealed a high level of anxiety, coupled with common instances of bullying, reflecting poorly on participants mental health. Anxiety issues were indeed reported in every included studies. Participants expressed both a general anxiety about school and specific anxiety related to schoolwork factors and/or to environmental or sensory factors. Anxiety and its detrimental effects were mainly reported by participants enrolled in a mainstream school or about their former mainstream school experience.

Most of the included studies (9 out of 12) reported anxiety related to school and/or schoolwork. For example, participants described difficulties adjusting with the hectic daily pace of school life and their busy schedule (Aubineau & Blicharska, 2020), the fear of being reprimanded (Goodall & MacKenzie, 2019), and the overall academic pressure (Cunningham, 2020; Tomlinson et al., 2021). In particular, homework was cited as triggering both dislike and anxiety (Dillon et al., 2016; Goodall, 2019; Cunningham, 2020). Exam pressure was also mentioned in some studies (Aubineau & Blicharska, 2020; Hill, 2014; Tomlinson et al., 2021). Interestingly, the related anxiety seemed to be caused by sensory and environmental factors (e.g., noise, unfamiliarity, break of routine) in addition to purely performance factors.

Anxiety related to sensory and environmental factors was the most common reported item across all the included studies (11 out of 12). One participant from Goodall (2020) described (mainstream) school as follows: “There are just too many people—it is too noisy, busy, and stressful for children with autism” (p. 1303). Noise, crowds, proximity of people, and unpredictability were indeed repeatedly cited as anxiety triggers. Participants mentioned several collective places that were perceived as particularly stressful. For example, in addition to signalling a transition, the corridors were viewed as a place of chaos and as being too noisy (Hill, 2014; Goodall, 2018b; Goodall and MacKenzie, 2019; Rainsberry, 2017; Tomlinson et al., 2021). One participant from Hill (2014) described navigating corridors as a dreading experience making them feel: “Really nervous. I feel baffled. Don’t know what’s happening. Just don’t know, don’t know who is coming. Can’t see them. Don’t know in which direction they are coming from. That makes me worry” (p. 83).

This was especially reported by participants from secondary schools, where changes of classrooms are more frequent. The cafeteria and other shared spaces were also disliked and avoided as much as possible (Aubineau & Blicharska, 2020; Goodall & MacKenzie, 2019; Rainsberry, 2017; Tomlinson et al., 2021). Finally, the classroom itself was perceived by many as too noisy, especially in the presence of a disorganized or substitute teacher (Cunningham, 2020; Goodall, 2018b; Hummerstone & Parsons, 2021; Tomlinson et al., 2021).

In addition to general and specific anxiety, bullying was also reported in many studies, mainly by participants enrolled in a mainstream school or about their former mainstream school experience. Bullying could be verbal (Aubineau & Blicharska, 2020; Goodall, 2018b, 2019; Goodall & MacKenzie, 2019; Hill, 2014), physical (Goodall, 2018b, 2019; Goodall & MacKenzie, 2019), and sometimes even amounted to sexual harassment (Goodall & MacKenzie, 2019; Goodall, 2018b). Participants were mainly bullied by their peers, although harassment or misconduct from teachers was also present but not always identified as bullying.

Not surprisingly, the negative impact of their school experience on participants mental health was noted in several studies. Although not widespread, these reports involved mentions of anger (e.g., in Dillon et al., 2016), depression (e.g., in Goodall, 2018b; Tomlinson et al., 2021), or eating disorder, self-harm, and suicidal ideation (e.g., in Tomlinson et al., 2021). One participant from Goodall (2018b) described their former experience of mainstream school as follows: “School was always awful. I went through a bit of severe depression. I kept on saying, every time some bad things happened, that I wished I was dead. I was always dreading it” (p. 6).

Identity and Relational Experience

Overall, participants expressed a split opinion about being autistic, viewing it either as positive or negative, or not addressing it. What seemed of greater importance to participants, however, was to be allowed to be themselves and to be respected as such. For example, when describing their ideal school, a participant from Goodall (2019) called it the “school of identity—where people can be themselves” (p. 28). This respect included recognizing participants’ needs and individuality, but also their specificities and limits, for example, by not forcing them to interact with peers or forming friendships against their will (Goodall, 2020). Quite logically, autism understanding and acceptance was of great importance for participants, especially with regards to teaching staff.

Teachers indeed played a significant role in participants’ school experience. More than their teaching practices or abilities, it was their attitude and relational skills that impacted the participants the most. Across the included studies, participants referred to the importance of being understood, both as autistic and as their own person, and being listened to. Teachers’ awareness, understanding, and acceptance of autism was noted as crucial. However, here again, the attitude of the teachers appeared to matter more than their autism training or knowledge (e.g., Goodall, 2018b, 2019; Hummerstone & Parsons, 2021; Rainsberry, 2017; Tomlinson et al., 2021). As a participant from Goodall and MacKenzie (2019) stated: “It is a matter of taking the training and using it seriously and understanding that the child is their own person” (p. 511). The need to not being treated based on preconceived notions of autism or past experiences with other autistic children was also noted (e.g., Goodall, 2018b). Finally, in addition to their attitude towards autism, teachers’ relational skills were essential for participants, with teachers showing genuine concern and interest for each of their students being praised by participants (Goodall, 2019).

Regarding their relationship with their peers, autism understanding and acceptance were also central for participants with many reporting difficulties or incidents due to a lack of autism awareness (e.g., in Goodall & MacKenzie, 2019; Rainsberry, 2017; Tomlinson et al., 2021). Overall, participants described both interest for, but also difficulties with, social relations. Participants from mainstream schools expressed mixed feelings about their mainstream peers. Some showed interest for them, and a few explained actively observing them in order to learn social skills (e.g., in Hill, 2014). However, many of the participants also described their mainstream peers as being immature and causing distraction, thus indirectly reinforcing their anxiety issues (e.g., in Aubineau and Blicharska, 2020; Dillon et al., 2016; Hill, 2014). Feelings of loneliness, isolation, and exclusion were also reported in many cases (e.g., in Goodall, 2018b; Goodall & MacKenzie, 2019; Warren et al., 2021) , sometimes amounting to bullying, as previously described.

Notwithstanding the challenges encountered with social relations, friendship was noted as of central importance in most studies. Even though some participants expressly stated that they preferred being (left) alone and were more comfortable on their own, friendship was overall valued and desired, although not always experienced. Regarding their characteristics, the friendships formed by participants were quite exclusive and focused on a small number of close friends (sometimes only one), in contrary to the group friendships more common in their non-autistic peers. Friends were also sometimes used as academic and social support (e.g., in Dillon et al., 2016). Although the information was not available in all the included studies, for many participants, friends were also from a disabled or otherwise marginalized population (e.g., in Aubineau & Blicharska, 2020; Rainsberry, 2017; Warren et al., 2021). In most studies, a general appreciation for being among similar peers (either autistic, disabled, with special educational needs, or part of a specific program) was likewise reported. As one participant from Goodall (2019) said about their special education peers: “they are similar to me, have had similar problems and I can relate to them” (p. 26).

Learning Experience

Together, the included studies illustrated a quite balanced outcome between both learning successes and difficulties. When properly fostered, intense interests played a positive role in participants’ motivation to study and for their future academic and career prospects. Participants expressed no uniformity in preferred subjects or teaching practices. For example, some enjoyed working in—small and well managed—groups (Dillon et al., 2016), while for others, it was a source of anxiety (Aubineau & Blicharska, 2020). Some liked a specific subject because it was in line with their intense interest or because it was taught by their favorite teacher (Rainsberry, 2017). However, several mentioned the need for emotional and social learning in addition to the purely academic curriculum (e.g., in Cunningham, 2020; Dillon et al., 2016), and a common preference emerged for clear instructions and flexible pedagogical approaches.

Support and Accommodations

In response to the challenges faced regarding both the socio-emotional and sensory, identity and relational, or learning dimensions, most studies mentioned positive accounts of support and accommodations provided to the participants. The most cited and appreciated example was the availability of a quiet space where participants were allowed to isolate if needed. Teaching assistants, support staff, flexibility from teachers, and measures to enhance predictability, routine, and clarity were also noted, together with specialist interventions (e.g., speech therapists, social skills groups) and more personalized accommodations. For example, one participant from Tomlinson et al. (2021) had a “wristband which is green on one side, red on the other… I can flip it and people know whether to talk to me or not” (p. 11). However, a lack of support was also reported in some studies. In addition, some participants having left mainstream for special or home-based education indicated that in mainstream schools, “there was close to no support” (Goodall, 2018b, p.9) and that these schools “don’t support people with disabilities” (Goodall, 2020, p.1303) or “aren’t able to give the support or help with [autistic children’s] needs or challenging behavior” (Goodall, 2020, p.1302). Overall, when asked for potential improvements that could have been made, most participants referred to more opportunities to rest and a quieter environment.

Quite interestingly, a common concern regarding support and accommodation revolved around their sometimes harmful effects. Indeed, most studies reported instances of undesirable or counterproductive support and accommodations. This negative impact could result from different causes. Support and accommodations could be imposed on participants against their will, needs, and preferences (e.g., visual schedules [Goodall, 2018b]; support groups [Rainsberry, 2017]; forced friendships [Goodall & MacKenzie, 2019]), impede on participants opportunities to rest and relax (e.g., social skills training, speech or psychomotor interventions [Aubineau & Blicharska, 2020]), create difficulties in themselves (e.g., anxiety resulting from having to go before the bell to avoid the noise [Hill, 2014]), or hinder participants autonomy and their social inclusion (e.g., over-presence of assistant or special staff [Aubineau & Blicharska, 2020; Hill, 2014; Rainsberry, 2017; Tomlinson et al., 2021]).

In addition to, or in substitute of, the support and accommodations provided, participants also reported using their own strategies to cope with their daily school experience. However, these strategies relied mainly on avoidance or isolation techniques, thus impeding on the participants inclusion and well-being. For example, participants reported hiding their anxiety from others (Cunningham, 2020), hiding in the toilets (Goodall, 2019), avoiding some collective areas—including the cafeteria and therefore not eating (Aubineau & Blicharska, 2020; Goodall & MacKenzie, 2019; Hill, 2014), or leaving the classrooms or the school—and therefore missing classes (Goodall, 2018b; Tomlinson et al., 2021; Warren et al., 2021).

Mainstream and Special Settings

Overall, the experience of mainstream school was very divided, either positive or (highly) negative, with reports of both inclusion and exclusion, depending on the participants. In general, mainstream was seen as good for offering peer learning opportunities and fostering higher academic aims. However, a lack of support and a non-inclusive ethos, as well as overwhelming sensory and environmental challenges were commonly reported. Some participants also expressed skepticism on the possibility to include all the diversity of learners together and to manage conflicting needs, as exemplified in Goodall (2020):

It wouldn’t be fair on students if everybody was in one school because people learn at different speeds, some faster, some slower – this wouldn’t be right. I believe this isn’t right as the child might not be able to cope. It is just like an ingredient … like a big pot ... you can’t just throw every ingredient in … only certain ingredients work with other ingredients. (p. 1299)

Conversely, participants in special education, resources provisions, or special programs were strongly positive about their experience. Small-size classes, flexibility, a sensory-friendly environment, and teachers’ attitudes were reported as enhancing their school experience (Goodall, 2018b, 2019; Warren et al., 2021).

Finally, although only directly addressed by one study (Goodall, 2020), involved participants were quite vocal about the necessity for students to have a choice between different educational provisions, and advocated for individual school placement strategies. For them, inclusion was defined as belonging and feeling respected rather than being enrolled in a specific type of school. As participants stated, neither full mainstream, mainstream with resource provision, special, or autistic-only schools can be seen as the best option for all or most autistic students. Instead, they believed that “you should have a choice to go to mainstream or an alternative education,” “it is not fair to force,” and “it is not fair to make children go to mainstream school if they can’t cope or it doesn’t support them” (Goodall, 2020, p.1300). They agree that inclusion can happen in any type of school, and that autistic children should be placed “wherever it is best—as long as it is autism friendly” (Goodall, 2020, p.1300).

Discussion

Limitations

Before further analyzing the results of the present literature review and how they can inform conceptual issues around the right to education of autistic children, it appears important to highlight some of its limitations. As a literature review, the present study is dependent on the quality of the reviewed publications. Although this quality was carefully assessed, the review thus carries over the limitations and potential biases of the included studies. The review is also dependent on the primary data provided or not by the included publications. As such, no analysis was made based on an absence of data or mention, since it could not be established whether this absence was consequential or resulted from the original researchers’ design or reporting choices. In addition, most of the included studies presented only a small and non-representative sample of participants. The format of the literature review (rapid review) and its focus on qualitative studies also carries inherent limitations, especially regarding its scope. Finally, the fact that some stages of the search and selection process were carried out by one researcher only increases the risk for subjectivity and bias. Therefore, although carried out in a systematized manner, this literature review does not pretend to provide a definitive representative picture of the educational experience of all (European) autistic children, but rather attempts to offer an initial overview and act as an incentive towards more extensive research and reviews in this field.

Notwithstanding the limitations of this present literature review, important inferences can be made from the results, both regarding their comparison to the existing literature and their inputs to the conceptual discussions around the right to education of autistic children.

Comparison to the Existing Literature

Most of the results were in alignment with the existing literature on autistic children’s educational experience. Regarding the thematic of socio-emotional and sensory experience, the results supported the common findings from the literature on autistic students’ educational experience, which consistently report a higher anxiety level (Danker et al., 2016; Hebron & Humphrey, 2014; Lüddeckens, 2021), sensory overload (DePape & Lindsay, 2016; Tomlinson et al., 2020), higher risk of bullying (Lüddeckens, 2021; Roberts & Simpson, 2016; Tomlinson et al., 2020), including in comparison to other disabled students or other students with special educational needs (Symes & Humphrey, 2010; Williams et al., 2019), and poorer mental health (Danker et al., 2016; Hebron & Humphrey, 2014). Similarly, the findings on the importance of teachers’ attitudes and relational skills were coherent with other studies’ conclusions, where teachers’ understanding and flexibility is commonly identified as key to provide a positive educational experience for autistic students (Baric et al., 2016; Brownlow et al., 2021; Danker et al., 2016; DePape & Lindsay, 2016; Roberts & Simpson, 2016). The findings on the learning experience of autistic children also highlighted characteristics commonly found in other studies, such as the role of intense interests (Wood, 2021) or the variety of preferences and pedagogical needs of autistic students (Baric et al., 2016; Honeybourne, 2015). Finally, the results describing a mixed experience of mainstream inclusion were also mostly coherent with other publications, which regularly report both advantages and disadvantages in mainstream education for autistic children (Merry, 2020; Roberts & Simpson, 2016; Williams et al., 2019). The definition of inclusion given by participants, namely a feeling of belonging and of being respected rather than being in a specific type of school, was also in alignment with findings from other studies and reviews (Bailey & Baker, 2020; Lüddeckens, 2021).

In addition to confirming certain features commonly found in studies of autistic children’s educational experience, the results of the present literature review also highlighted some less identified elements. One of the main findings of the literature review was that autistic children experience overwhelming anxiety due to sensory and environmental factors. Indeed, while anxiety is commonly reported in autistic children’s educational experience, the role of sensory factors has only started to be fully identified (Howe & Stagg, 2016; Tomlinson et al., 2020). Regarding autistic children’s relation to peers and friendship, the present review pointed out a less documented aspect of autistic children’s friendship, namely their preference for being among similar peers. Finally, the results brought into light the potential counterproductive effects of support and accommodations. Although some publications had previously noted a demand for making the support as discrete as possible (DePape & Lindsay, 2016; Roberts & Simpson, 2016), these results further underline the need to design support and accommodations in a consultative, evolutive, and personalized manner.

Towards a Neurodiverse Interpretation of Quality Education

The literature review provided several inputs on a potential neurodiverse interpretation of quality education. First, regarding the topic of skills’ development and acquisition, the literature review underlined the diversity of autistic children as individual learners. Although a rights-based individual approach is recommended by the individual aims of education (CRC Committee, 2001, §8 and 9), pedagogies and sometimes accommodations offered to autistic children are often designed through a categorial approach. As shown by the literature review, this can lead to ready-to-use, inflexible methods being applied to all autistic children, which then often translates into potentially counterproductive support and accommodations. As found in other publications (Baric et al., 2016; Honeybourne, 2015), the review indicated a great variety in autistic children’s preferred learning methods and educational needs and preferences. Although some commonalities were found, such as a need for clear instructions and flexible approaches and a general dread of homework, participants differed greatly on, for example, their favorite subject, or preferred learning and information delivery methods. This highlights that, in order to provide quality education, each autistic child should be first and foremost considered as a unique learner rather than a standard member of the autistic or disabled population (Brownlow et al., 2021). In addition, the literature review also indicated a need for more emotional and social learning, which underlines the necessity to better integrate individualized non-academic skills training (e.g., social, emotional, communication, and life skills) within the educational curriculum of autistic children (Allen et al., 2020; Lundy & Tobin, 2019; Shevlin, 2019).

The overwhelming anxiety and widespread bullying captured by the literature review also seriously question the quality of the education provided to autistic children. The negative impact both anxiety and bullying have on mental health and academic performance is well documented (Hebron & Humphrey, 2014; Murphy et al., 2022). As such, they directly impede the development of autistic children’s skills, self-esteem, and personality. What is more, while anxiety and bullying is experienced by non-autistic children as well, the review indicated that some issues, for example, around sensory and environmental factors or relational differences, are specifically at play for autistic children. This underlines the importance of better integrating the issues of well-being and safety, and the specific questions they raise for autistic children (Bottroff et al., 2019; Merry, 2020), in the conceptualization of quality education.

Regarding the topic of autistic identity, as mentioned in the introduction, the identity aims have so far mainly focused on ethnic, linguistic, or religious issues. However, recent developments have emerged around the inclusion of autism within the topic of cultural diversity (Ashby, 2010). Indeed, the presence of the concept of “human diversity” in the text of the CRPD (Article 24 §1) coupled to the growing acknowledgement of an individual and collective autistic identity (Bertilsdotter-Rosqvist et al., 2020; Kapp, 2020; Silberman & Sacks, 2016) gives support for a better inclusion of autism within the discourse on identity and diversity in education. This is supported by the present literature review, which showed that being understood and accepted as their own autistic self was of the uttermost importance to autistic children. Although still at a preliminary stage, the acknowledgement of autism as an identity and a potential cultural minority could open new legal avenues, for example, towards the respect of autistic children’s neurodevelopmental and communication specificities as part of requirements for quality education.

Towards a Neurodiverse Interpretation of Inclusive Education

As briefly mentioned in the introduction, the current interpretation of Article 24 of the CRPD imposes mainstream inclusion at the expense of other alternative options. While most European countries have so far maintained at least some offers of special or mixed options, the perennity of those is therefore at risk. Indeed, in its latest monitoring, the CRPD Committee has consistently criticized special education. For example, it has denounced “the persistence of a dual education system [in the UK] that segregates children with disabilities in special schools, including based on parental choice” (CRPD Committee, 2017, §52), or considered the establishment of “model schools” for autistic children in Portugal as “a form of segregation and discrimination” (CRPD Committee, 2016b, §44).

Although the position of the Committee can be related to the fight against historical segregation of disabled children in poor quality special schools (Merry, 2020), it should not lead to counterproductive and detrimental effects on autistic children’s right to education. Indeed, the present literature review offered a critical insight on the current hegemony of mainstream inclusion. Firstly, when a definition was provided, autistic children defined inclusion as a feeling of belonging and of being respected rather than a specific type of school. This highlights that, contrary to the current position of the CRPD Committee, inclusion can be experienced in other settings than mainstream schools.

Secondly, while support measures and reasonable accommodations are the central mechanisms of inclusive education, they might not be enough to support autistic children’s needs within a mainstream environment. Indeed, through the literature review, the most reported item was the anxiety caused by sensory and environmental factors. Sensory specificities are indeed a central though traditionally overlooked feature of autism (Bogdashina, 2016) and their role in triggering anxiety and social and academic challenges has just slowly started to be recognized (Howe & Stagg, 2016). As reported by the participants, such specificities can render the experience of mainstream environment unsustainable for autistic children. However, because these specificities are rather unique to autistic children, often quite foreign for neurotypical staff, and in conflict with some core characteristics of mainstream schools (e.g., class size, collectivity), providing related support or accommodations is made especially difficult (Moore, 2007; Wing, 2007). In addition, while the lack of accommodation was sometimes given as a reason for negative mainstream experience, mainstream settings were also viewed by some participants as unsuitable regardless of the accommodations provided. On the contrary, some reported a positive experience of mainstream school amid a lack of, or with only few accommodations. This underlines that the relevance, or not, of mainstream placements is individual and does not only depend on the implementation of support measures and reasonable accommodations. Overall, the diversity of experiences, needs, and preferences reported by the participants clearly indicates that one-size does not fit all and that there is a need for a diverse educational offer (Goodall, 2018a; Marshall & Goodall, 2015; Merry, 2020). This highlights the necessity to interpret the concept of inclusive education in a deeper and more complex manner, instead of equaling it to mainstream inclusion only (Boyle et al., 2021; Norwich & Koutsouris, 2021; Veerman, 2022). While this can be prioritized, it appears crucial that states provide quality and inclusive special education options as well. The risk otherwise is to fully negate the right to education for children, including autistic children, for whom mainstream settings, despite reasonable accommodations, are not able to provide an education respectful of their rights.

Conclusion and Further Research

This literature review has brought forward important insights regarding autistic children educational experience, in particular the anxiety they face due to sensory and environmental factors, their need to be understood and respected as their own (autistic) person, and the requirement of diverse and personalized support and pedagogical approaches. These results in turn allowed to inform important conceptual questions about their right to education. Regarding the conception of quality education, while autistic children might share a diagnostic and common neurological features, they might greatly differ in their educational needs. When focusing on developing their skills, a careful balance between a categorial and individual approach is therefore required. In addition, both scholars and decision-makers need to acknowledge that fostering a quality education also includes adopting a supportive approach to autistic children’s individual and collective identity. The specific issues autistic children face concerning bullying and anxiety, and the impact this has on their right to education, also require to be given full consideration. Finally, regarding inclusive education, a wider conception of inclusion than the one centering on a mainstream versus special school opposition appears necessary. Overall, the literature review underlined the necessity to preserve and develop the availability of and accessibility to diverse quality and inclusive educational offers for autistic children. On this note, there appears to be a need for a greater involvement of legal science in better conceptualizing the right to education of autistic children, including through their lived experience. Education is a legal right and autistic children are legal subjects, and legal scholars must therefore participate in the multidisciplinary discourse on this topic. Finally, the literature review also highlighted a need for more research on autistic children’s educational experience that would cover all the spectrum, including non-speaking autistic children (Fletcher-Watson et al., 2019). Although not without challenges, such research appears indeed necessary to access a thorough and comprehensive understanding of autistic children’s educational experience and to better conceptualize and implement their right to education.

Data Availability

The data used in this article consist of published academic articles that are all listed in the References section (the relevant entries are highlighted in bold).

Notes

Ratified by all the members states of the Council of Europe, except Monaco and Switzerland.

Ratified by the totality of the European states.

Ratified by the totality of the European states, except Liechtenstein and Moldova.

Master student employed as a research assistant.

References

References included in the literature review are signaled with a *

Allen, K.-A., Boyle, C., Lauchlan, F., & Craig, H. (2020). Using social skills training to enhance inclusion for students withs asd in mainstream schools. In C. Boyle, J. Anderson, A. Page, & S. Mavropoulou (Eds.), Inclusive education: Global issues and controversies (pp. 202–215). Brill.

American Psychiatry Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders – DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatry Association. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

Anastasiou D., Gregory M., & Kauffman, J. K. (2018). Article 24: Education. In I. Bantekas, M. A. Stein & D. Dimitri (Eds.), The UN convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. A commentary (pp. 656–704). Oxford University Press.

Arduin, S. (2019). The expressive dimension of the right to inclusive education. In G. de Beco, S. Quinlivan, & J. E. Lord (Eds.), The right to inclusive education in international human rights law (pp. 141–166). Cambridge University Press.

Ashby, C. (2010). The trouble with normal: The struggle for meaningful access for middle school students with developmental disability labels. Disability & Society, 25(3), 345–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687591003701249

*Aubineau, M., & Blicharska, T. (2020). High-functioning autistic students speak about their experience of inclusion in mainstream secondary schools. School Mental Health, 12(3), 537–555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-020-09364-z.

Bailey, J., & Baker, S. T. (2020). A synthesis of the quantitative literature on autistic pupils’ experience of barriers to inclusion in mainstream schools. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 20(4), 291–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12490

Baric, V. B., Hellberg, K., Kjellberg, A., & Hemmingsson, H. (2016). Support for learning goes beyond academic support: Voices of students with Asperger’s disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Autism, 20(2), 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315574582

Barua, M., Bharti, & Shubhangi, V. (2019). Inclusive education for children with autism: Issues and strategies. In S. Chennat (Ed.) Disability inclusion and inclusive education (pp. 83–108). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0524-9_5.

Bertilsdotter-Rosqvist, H., Chown, N., & Stenning, A. (2020). Neurodiversity studies: A new critical paradigm. Routledge.

Bogdashina, O. (2016). Sensory perceptual issues in autism and Asperger syndrome: Different sensory experiences different perceptual worlds. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Bottroff, V., Spears, B., & Slee, P. (2019). Bullying issues for students on the autism spectrum and their families. In R. Jordan, J. Roberts, & K. Hume (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of autism and education (pp. 466–481). SAGE.

Boyle, C., & Anderson, J. (2021). Inclusive education and the progressive inclusionists. In U. Sharma & S. J. Salend (Eds.), The Oxford encyclopedia of inclusive and special education (pp. 883–894). Oxford University Press.

Boyle, C., Koutsouris, G., Mateu, A. S., & Anderson, J. (2021). The matter of ‘evidence’ in the inclusive education debate. In U. Sharma & S. J. Salend (Eds.), The Oxford encyclopedia of inclusive and special education (pp. 1041–1054). Oxford University Press.

Brownlow, C., Lawson, W., Pillay, Y., Mahony, J., & Abawi, D. (2021). ‘Just ask me’: The importance of respectful relationships within schools. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.678264.

Cera, R. (2015). National legislations on inclusive education and special educational needs of people with autism in the perspective of Article 24 of the CRPD. In V. Della Fina (Ed.), Protecting the rights of people with autism in the fields of education and employment (pp. 79–108). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-13791-9.

Chown, N., Robinson, J., Beardon, L., Downing, J., Hughes, L., Leatherland, J., Fox, K., Hickman, L., & MacGregor, D. (2017). Improving research about us, with us: A draft framework for inclusive autism research. Disability & Society, 32(5), 720–734. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1320273

Chown N. (2020). “Neurodiversity”. In F. Volkmar (Ed.), Encyclopedia of autism spectrum disorders. Springer Reference Live. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-1-4614-6435-8_102298-2

Clark, T. (2019). A curriculum to support students with autism and special talents and abilities. In R. Jordan, J. Roberts, & K. Hume (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of autism and education (pp. 315–321). SAGE.

Council of Europe (1952). Protocol 1 to the European convention for the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms. ETS 9.

Courtis C., & Tobin J. (2019). Article 28: The right to education. In J. Tobin (Ed.), The UN convention on the rights of the child. A commentary (pp. 1056–1115). Oxford University Press.

CRC Committee (2001). General comment No. 1 Article 29 (1), The aims of education. CRC/GC/2001/1.

CRPD Committee (2016a). General comment No. 4, Article 24: Right to inclusive education. CRPD/C/GC/4.

CRPD Committee (2016b). Concluding observations on Portugal. CRPD/C/PRT/CO/1.

CRPD Committee (2017). Concluding observations on the UK. CRPD/C/GBR/CO/1.

*Cunningham, M. (2020). ‘This school is 100% not autistic friendly!’ Listening to the voices of primary-aged autistic children to understand what an autistic friendly Primary school should be like. International Journal of Inclusive Education.https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2020.1789767

Danker, J., Strnadová, I., & Cumming, T. M. (2016). School Experiences of students with autism spectrum disorder within the context of student wellbeing: A review and analysis of the literature. Australasian Journal of Special Education, 40(1), 59–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/jse.2016.1

de Beco, G. (2014). The right to inclusive education according to Article 24 of the UN convention on the rights of persons with disabilities: Background, requirements and remaining questions. Netherlands Quarterly Human Rights, 32(3), 263–287.

de Beco, G. (2019). Comprehensive legal analysis of Article 24 of the convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. In G. de Beco, S. Quinlivan & J. E. Lord (Eds.) The Right to Inclusive Education in International Human Rights Law (pp. 58–92). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316392881

DePape, A.-M., & Lindsay, S. (2016). Lived experiences from the perspective of individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 31(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357615587504

*Dillon, G. V., Underwood, J. D. M., & Freemantle, L. J. (2016). Autism and the U.K. secondary school experience. Focus on autism and other developmental disabilities, 31(3), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357614539833.

Fletcher-Watson, S., Adams, J., Brook, K., Charman, T., Crane, L., Cusack, J., Leekam, S., Milton, D., Parr, J. R., & Pellicano, E. (2019). Making the future together: Shaping autism research through meaningful participation. Autism, 23(4), 943–953. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318786721

Freeman, O.A.M. (2020). Future trends in education. In W. Leal Filho, A. M. Azul, L. Brandli, P. G. Özuyar & T. Wall (Eds.), Quality education. Encyclopedia of the UN sustainable development goals. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95870-5_60.

Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., & Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

Goodall, C. (2018a). Mainstream is not for all: The educational experiences of autistic young people. Disability & Society, 33(10), 1661–1665. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018.1529258

*Goodall, C. (2018b). ‘I felt closed in and like i couldn’t breathe’: A qualitative study exploring the mainstream educational experiences of autistic young people. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments, 3, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/2396941518804407.

*Goodall, C. (2019). ‘There is more flexibility to meet my needs’: Educational experiences of autistic young people in mainstream and alternative education provision. Support for Learning, 34(1), 4–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12236.

Goodall, C. (2021). Understanding the voices and educational experiences of autistic young people. Routledge.

*Goodall, C., & MacKenzie, A. (2019). ‘What about my voice? Autistic young girls’ experiences of mainstream school. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 34(4), 499–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2018.1553138.

*Goodall, C. (2020). Inclusion is a feeling, not a place: A qualitative study exploring autistic young people’s conceptualisations of inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(12), 1285–1310. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1523475.

Gouvernement de la République française (2018). Stratégie nationale pour l’autisme au sein des troubles du neuro-développement. https://handicap.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/strategie_nationale_autisme_2018.pdf. Accessed 27 Apr 2023.

Hebron, J., & Humphrey, N. (2014). Mental health difficulties among young people on the autistic spectrum in mainstream secondary schools: A comparative study. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 14(1), 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2012.01246.x

*Hill, L. (2014). ‘Some of it i haven’t told anybody else’: Using photo elicitation to explore the experiences of secondary school education from the perspective of young people with a diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorder. Educational and Child Psychology, 31(1), 79–89.

Honeybourne, V. (2015). Girls on the autism spectrum in the classroom: Hidden difficulties and how to help. Good Autism Practice, 16(2), 11–20.

Howe, F. E., & Stagg, S. D. (2016). How sensory experiences affect adolescents with an autistic spectrum condition within the classroom. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(5), 1656–1668. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2693-1

Huijg D. D. (2020). Neuromormativity in theorizing agency. In H. Bertilsdotter-Rosqvist, N. Chown, & A. Stenning (Eds.), Neurodiversity studies. A new critical paradigm (pp. 213–217). Routledge.

*Hummerstone, H., & Parsons, S. (2021). What makes a good teacher? Comparing the perspectives of students on the autism spectrum and staff. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 36(4), 610–624. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2020.1783800.

Hyatt, C., & Hornby, G. (2017). Will UN Article 24 lead to the demise of special education or to its re-affirmation? Support for Learning, 32(3), 288–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12170

Individuals With Disabilities Education Act of 2004, 20 U.S.C. § 1400.

Jaarsma P., & Welin S. (2012). Autism as a natural human variation: Reflections on the claims of the neurodiversity movement. Health Care Analysis, 20(1), 20–30. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21311979/. Accessed 27 Apr 2023.

Jordan, R. (2008). The Gulliford lecture: Autistic spectrum disorders: A challenge and a model for inclusion in education. British Journal of Special Education, 35(1), 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8578.2008.00364.x

Jordan, R. (2019). Crystal gazing. In R. Jordan, J. Roberts, & K. Hume (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of autism and education (pp. 618–624). SAGE.

Kanter, A. (2019). The right to inclusive education for students with disabilities under international human rights law. In G. de Beco, S. Quinlivan, & J. E. Lord (Eds.), The right to inclusive education in international human rights law (pp. 15–57). Cambridge University Press.

Kapp, S. K. (2020). Autistic community and the neurodiversity movement: Stories from the frontline. Palgrave Mcmillan.

Lile, H. S. (2021). International law on the aims of education: The convention on the rights of the child as a legal framework for school curriculums. Routledge.

Lollini, A. (2018). Brain equality: Legal implications of neurodiversity in a comparative perspective. NYU Journal of International Law and Politics, 51(19), 69–134.

Loomes, R., Hull, L., & Locke Mandy, W. P. (2017). What is the male-to-female ratio in autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(6), 466–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.013

Lorcan, K., Hattersley, C., Molins, B., Buckley, C., Povey, C., & Pellicano, E. (2016). Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism, 20(4), 442–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315588200

Lüddeckens, J. (2021). Approaches to inclusion and social participation in school for adolescents with autism spectrum conditions (ASC) a systematic research review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 8(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-020-00209-8

Lundy L., & Tobin J. (2019). Article 29: The aims of education. In J. Tobin (Ed.), The UN convention on the rights of the child. A commentary (pp. 1116–1152). Oxford University Press.

Marshall, D., & Goodall, C. (2015). The right to appropriate and meaningful education for children with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(10), 3159–3167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2475-9

Merry, M. S. (2020). Do inclusion policies deliver educational justice for children with autism? An ethical analysis. Journal of School Choice, 14(1), 9–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2019.1644126

Milton, D. (2017). Difference versus disability: implications of characterization of autism for education and support. In R. Jordan (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Autism and Education. SAGE.

Moore, C. (2007). Speaking as a parent: Thoughts about educational inclusion for autistic children. In R. Cigman (Ed.), Included or excluded? (pp. 34–41). Routledge.

Murphy, D., Leonard, S. J., Taylor, L. K., & Santos, F. H. (2022). Educational achievement and bullying: The mediating role of psychological difficulties. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 1487–1501. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12511

Norwich, B., & Koutsouris, G. (2021). Addressing dilemmas and tensions in inclusive education. In U. Sharma & S. J. Salend (Eds.), The Oxford encyclopedia of inclusive and special education (pp. 1–20). Oxford University Press.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hrobjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ.. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Pellicano, E., Dinsmore, A., & Charman, T. (2014). What should autism research focus upon? Community views and priorities from the United Kingdom. Autism, 18(7), 756–770. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361314529627

Pellicano, E., Bölte, S., & Stahmer, A. (2018). The current illusion of educational inclusion. Autism, 22(4), 386–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318766166

Pope, C. (2000). Qualitative research in health care: Analysing qualitative data. BMJ, 320(7227), 114–116. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114

*Rainsberry, T. (2017). An exploration of the positive and negative experiences of teenage girls with autism attending mainstream secondary school. Good Autism Practice, 18(2), 15–31.

Reyes, M. S. C. (2019). Inclusive education: Perspectives from the UN committee on the rights of persons with disabilities. In G. de Beco, S. Quinlivan, & J. E. Lord (Eds.), The right to inclusive education in international human rights law (pp. 403–423). Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, J., & Simpson, K. (2016). A review of research into stakeholder perspectives on inclusion of students with autism in mainstream schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(10), 1084–1096. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2016.1145267

Runswick-Cole, K., Mallett, R., & Timimi, S. (2016). Re-thinking autism. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Saldaña, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE.

Shevlin, M. (2019). Moving towards school for all: Examining the concept of educational inclusion for disabled children and young people. In G. de Beco, S. Quinlivan & J. E. Lord (Eds.), The right to inclusive education in international human rights law (pp. 97–121). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316392881

Silberman, S., & Sacks, O. W. (2016). Neurotribes: The legacy of autism and the future of neurodiversity. Avery.

Singer, J. (2017). NeuroDiversity: The birth of an idea. Judy Singer.

Special Educational Needs and Disability Act. (2001). Parliament of the United Kingdom

Srivastava, A., & Thomson, B. S. (2009). Framework analysis: A qualitative methodology for applied policy research. JOAAG, 4(2), 72–79. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2760705

Stack K., Symonds, J. E., & Kinsella, W. (2021). The perspectives of students with autism spectrum disorder on the transition from primary to secondary school. A systematic literature review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2021.101782

Symes, W., & Humphrey, N. (2010). Peer-group indicators of social inclusion among pupils with autistic spectrum disorders (ASD) in mainstream secondary schools: A comparative study. School Psychology International, 31(5), 478–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034310382496

Tomasevski, K. (2006). Right to education. Primer n. 3. https://www.right-to-education.org/sites/right-to-education.org/files/resource-attachments/Tomasevski_Primer%203.pdf

Tomlinson, C., Bond, C., & Hebron, J. (2020). The school experiences of autistic girls and adolescents: A systematic review. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 35(2), 203–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2019.1643154

*Tomlinson, C., Bond, C., & Hebron, J. (2021). The mainstream school experiences of adolescent autistic girls. European Journal of Special Needs Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2021.1878657.

Tong, A., Flemming, K., McInnes, E., Oliver, S., & Craig, J. (2012). Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12(1), 181. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-12-181

Tricco, A. C., Antony, J., Zarin, W., Strifler, L., Ghassemi, M., Ivory, J., Perrier, L., Hutton, B., Moher, D., & Straus, S. E. (2015). A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Medicine, 13(1), 224. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0465-6

United Nations General Assembly. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. United Nations, Treaty Series, 1577, 3.

United Nations General Assembly (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities and its optional protocol. A/RES/61/106.

Veerman, P. (2022). The best interests of the child and the right to inclusive education. The International Journal of Children’s Rights, 30(2), 499–523. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718182-30010012

*Warren, A., Buckingham, K., & Parsons, S. (2021). Everyday experiences of inclusion in primary resourced provision: The voices of autistic pupils and their teachers. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 36(5), 803–818. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2020.1823166.

Williams, E. I., Gleeson, K., & Jones, B. E. (2019). How pupils on the autism spectrum make sense of themselves in the context of their experiences in a mainstream school setting: A qualitative metasynthesis. Autism, 23(1), 8–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361317723836

Wilson, S., Hean, S., Abebe, T., & Heaslip, V. (2020). Children’s experiences with child protection services: A synthesis of qualitative evidence. Children and Youth Services Review, 113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104974

Wing, L. (2007). Children with autistic spectrum disorders. In R. Cigman (Ed.), Included or excluded? (pp. 34–41). Routledge.

Wood, R. (2021). Autism, intense interests and support in school: From wasted efforts to shared understandings. Educational Review, 73(1), 34–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2019.1566213

World Health Organization. (2019). International classification of diseases – ICD-10. https://www.who.int/classifications/icd/icdonlineversions/en/. Accessed 27 Apr 2023.

Zuber, W. J., & Webber, C. (2019). Self-advocacy and self-determination of autistic students: A review of the literature. Advances in Autism, 5(2), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1108/AIA-02-2018-0005

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Professor Linda Gröning and PhD Ingun Fornes for their supervision and support, to Professor Marit Skivenes for her advice and guidance, and to Daniel Lyngseth Fenstad for his work as research assistant during the literature review.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Bergen (incl Haukeland University Hospital) This paper is part of an individual PhD project funded by the University of Bergen, Faculty of Law.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ducarre, L.M. Informing Conceptual Issues Related to Autistic Children’s Right to Education Through a Literature Review of Their Lived Experience. Rev J Autism Dev Disord (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-023-00375-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-023-00375-5