Abstract

Aim

The mode of childbirth delivery can influence the child’s future health and the aim of this study was to explore the association between the delivery mode and the prevalence of early childhood caries.

Methods

We searched the PubMed, Google Scholar and Cochrane databases up to September 15, 2020. Two independent reviewers screened the papers for relevance, extracted data and assessed the risk of bias with the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale. We performed a random effects meta-analysis to pool the prevalence of early childhood caries according to the mode of delivery.

Results

The authors included 11 studies in the review, comprising 47,688 children with vaginal delivery and 10,994 with caesarean section (C-section). The publication years ranged from 1997 to 2020 and included birth cohorts, cross-sectional, register-based and case–control studies. We assessed three publications with low or moderate risk of bias. The median caries prevalence in the C-section group was 56.4% compared to 45.9% in the vaginal group and this difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05). The pooled overall odds ratio was 1.48 (95% CI 1.07–2.05) indicating a weak but statistically significant trend towards a higher caries occurrence among children delivered with C-section. The certainty of this finding was low due to heterogeneity and inconsistencies across the studies.

Conclusion

We found a weak but inconsistent association between the mode of delivery and the prevalence of early childhood caries. Further studies based on representative, prospective cohorts reporting a standardized core outcome set are required to answer the research question with higher certainty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Early childhood caries (ECC) is defined as the presence of one or more decayed, missed or filled surface in any primary tooth of a child under 6 years of age (Tinanoff et al. 2019). It is a common condition and more than 600 million children worldwide are estimated to suffer from untreated caries in their deciduous teeth (Marcenes et al. 2013). The severe forms of ECC may cause difficulties to eat, sleep and attaining school due to loss of tooth substance and pain (Anil and Anand 2017; Pitts et al. 2017). A systematic review has reported more than 100 unique biological, genetic, social and behavioural risk factors for early childhood caries in a complex interplay (Kirthiga et al. 2019). Among them, maternal and perinatal risk factors, such as preterm birth and gestational age, have been investigated in relation to ECC with mixed results (Boustedt et al. 2020; Occhi-Alexandre et al. 2020; Twetman et al. 2020). In this context, the mode of delivery is of particular interest, since the frequency of caesarean section (C-section) on maternal request has increased unprecedented over the recent decades (Begum et al. 2020) and it is important to have solid information if this may affect the future oral health of the child. To our knowledge, the association between the mode of delivery and ECC has previously been addressed in one systematic review (Antão et al. 2019). Based on four studies, the authors found no consistent relationship between the birth mode and the caries risk. However, the search for relevant literature was limited up to year 2015, and consequently, we found it of interest to update this information. The aim of this study was to systematically examine and pool the available literature on the mode of delivery and caries prevalence in the primary dentition. The focused question was “Is there an association between the mode of delivery (C-section vs. vaginal delivery) and the prevalence of early childhood caries?”.

Methods

We conducted this systematic review according to a predefined plan and followed the PRISMA statement (Moher et al. 2009). The PECO was: Population—Toddlers and preschool children, 2–6 years of age; Exposure—Delivery through caesarean section (CS); Comparison—Vaginal delivery (V); Outcome—Prevalence of early childhood caries in the primary dentition up to 6 years of age. The authors included prospective studies (birth cohorts), cross-sectional studies, case–control designs and register-based studies. Articles reporting convenience samples, case series and case reports were excluded. The study protocol was not preregistered in a publicly assessable database.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following electronic databases were searched from inception up to 15 September 2020: PubMed, Google Scholar and the Cochrane Oral Health Group’s Trials Register. The search words used were [(preschool child OR infant) AND (mode of delivery OR caesarean section OR C-section OR vaginal birth OR childbirth OR risk factors) AND (dental caries OR early childhood caries OR tooth decay)]. Only original peer-reviewed studies published with at least full abstracts and tables in English were eligible for inclusion. We excluded narrative reviews and grey literature, such as textbooks, conference papers, monographs and thesis. Clinical trials.gov was used to identify registered ongoing studies by combining the phrase “delivery mode” with “dental caries”. The reference lists of all identified studies, including one systematic review, were hand-searched for additional studies.

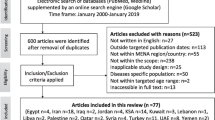

Selection of studies

Two authors (ST, KB) assessed the titles and abstracts of potentially eligible studies independently. If there was any doubt, the authors ordered the full-text papers for further evaluation. Any disagreement was resolved by discussions with a third author (JD). A flowchart of the study selection is shown in Fig. 1. The excluded studies and the main reason for their exclusion are listed in supplementary Table S1.

Data extraction and management

Two examiners (ST, KB) read the full papers and extracted data independently. The authors tabulated the following data: first author, year of publication, country of origin, study design, sample size, follow-up age, method and level of caries scoring, the number of examiners, calibration of examiners and sample size calculation. The outcome measure was prevalence of caries (decayed, missed and filled primary teeth > 0, and/or non-cavitated enamel lesions > 0) on subject level, expressed as percent. In studies, where data were unclear or missing, we contacted the corresponding author by e-mail for clarifications. If authors failed to provide additional data after two reminders, the publication was excluded.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Each study was independently examined for the risk of bias by two authors (ST, KB). Any disagreement was discussed within the whole author group. We used the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) to assess the quality of the included case–control, cohort and cross-sectional studies as suggested by Wells and co-workers (2014). We omitted item number four under the selection domain (“Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study”) and the maximum score was, therefore, eight stars. An overall assessment of the risk of bias was made for each included study: ≥ 7 stars = low risk of bias, 6 stars = moderate risk of bias, and ≤ 5 stars = high risk of bias. The risk of bias across the included studies was assessed with the GRADE approach (Guyatt et al. 2011).

Data synthesis

The authors conducted a narrative synthesis of the included studies and made a Chi-squared test to compare the medium prevalence of caries between the two birth groups. We applied unadjusted dichotomous data (caries vs. caries-free) to calculate the odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals for each separate study. The caries prevalence according to mode of delivery was then pooled in a random effects model using the Review Manager 5.3 tool (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). The clinical heterogeneity was assessed by examining the characteristics of the studies, the similarity between the types of participants and the outcomes of the included studies in this review.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

The authors included 11 studies covering 58,662 children in this review of which 47,688 had a vaginal delivery and 10,994 were born through C-section. The main characteristics are listed in Table 1. Six studies were cross-sectional trials (Zhou et al. 2011; Garcia-Castro and Perona-Miguel de Priego 2017; Shanthosh Raj et al. 2018; Pattanaporn et al. 2018; Sridevi et al. 2018; Korolenkova et al. 2020), two utilized population registers (Barfod et al. 2012; Brandquist et al. 2017), one was based on a prospective birth cohort (Boustedt et al. 2018) and two had a case–control design (Peretz and Kafka 1997; Nakai et al. 2016). The number of participating children per study ranged from 100 to 55,092 with a median value of 352. Four studies were from Europe (Barfod et al. 2012; Brandquist et al. 2017; Boustedt et al. 2018; Korolenkova et al. 2020), five from Asia (Zhou et al. 2011; Pattanaporn et al 2013; Nakai et al. 2016; Sridevi et al. 2018; Shanthosh Raj et al. 2018), one from South America (Garcia-Castro and Perona-Miguel de Priego 2017) and one from Israel (Peretz and Kafka 1997). The publication years ranged from 1997 to 2020. The threshold for caries detection was based on dentin (cavitated) level in 10 studies and only one scored non-cavitated early enamel lesions in addition to cavities (Boustedt et al. 2018). In general, bitewing radiographs were not used, except for one study, in which radiographs were captured based on individual indications (Boustedt et al. 2018). The number of clinical examiners ranged from one to six but few of the included publications reported data on examiner calibration and reliability tests. Caries status was scored at different ages, ranging from 8 months up to 6 years of age.

Quality assessment

The risk of bias is shown in Table 2. One of the included studies had a low risk of bias (Brandquist et al. 2017), two displayed a moderate risk (Zhou et al. 2011; Boustedt et al. 2018) and eight had a high risk of bias (Peretz and Kafka 1997; Barfod et al. 2012; Pattanaporn et al. 2013; Nakai et al. 2016; Garcia-Castro and Perona-Miguel de Priego 2017; Sridevi et al. 2018; Shanthosh Raj et al. 2018; Korolenkova et al. 2020). All studies except three scored at least one star in each of the three domains of “selection”, “comparability” and “outcome”. The main weaknesses were lack of representativeness, small sample sizes and outcome assessments. The GRADE certainty rating across the studies was very low.

Early childhood caries

The prevalence of early childhood caries ranged from 5.3% to 84.6% (median 56.4%) in the C-section group and from 6.1% to 59.6% (mean 45.9%) in the vaginal group. This difference in proportions was statistically significant (p < 0.05). The crude univariate odds ratio (OR) for the separate studies is shown in Table 3. There was a considerable inconsistency between the studies. The prevalence of ECC was significantly higher (p < 0.05) among the C-section children in five studies (Peretz and Kafka 1997; Pattanaporn et al. 2013; Garcia-Castro and Perona-Miguel de Priego 2017; Boustedt et al. 2018; Shanthosh Raj et al. 2018) and four reported no significant difference between the two modes of delivery (Barfod et al. 2012; Zhou et al. 2013; Sridevi et al. 2018; Korolenkova et al. 2020). One study found significantly more caries in the vaginal group (Brandquist et al. 2017) but the caries prevalence was very low in both groups. When the studies were pooled in a meta-analysis (Fig. 2), the overall OR was 1.48 (95% CI 1.07–2.05) indicating a weak but statistically significant trend of a higher prevalence of early childhood caries among children delivered with C-section. The heterogeneity was very high with an I2 value of 86% (Tau2 = 0.22).

Discussion

The mode of delivery can influence the child’s future health with an increased risk of asthma and obesity when delivered with C-section (Keag et al. 2018). Caesarean delivery affects the biodiversity of the gut microbiota in infants (Bäckhed et al. 2015) and similar observations are available from the oral and salivary microbiome (Nelun Barfod et al. 2011; Boustedt et al. 2015; Li et al. 2018). Infants born by C-section seem initially to have a less diverse salivary microbiota and harbour fewer beneficial health-associated species bacteria compared to children with vaginal birth, albeit a recovery seems to appear with age (Dzidic et al. 2018). Whether or not such altered colonization pattern during the first year of life do have a long-term consequences for child’s oral health is, however, not clear. In this study, we found no firm evidence of an elevated prevalence of early childhood caries levels in C-section children. Nevertheless, in contrast to the previous systematic review (Antão et al. 2019), we noticed a weak but statistically significant tendency towards a higher caries prevalence in the C-section group. The certainty of this finding was, however, low due to inconsistencies and a high risk of bias in the majority of the included publications. Notably, even the three studies with moderate and low risk of bias displayed conflicting findings.

Results from meta-analyses of observational studies are in general more hazardous than results from randomised controlled trials. Due to the limited number of studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria, we combined results from publications with different designs in our analyses, which meant that various methods of sample selection and caries detection were mixed. In, addition, some of the included studies targeted ECC and its risk factors and were, therefore, not designed or power calculated for analyses related to mode of delivery. We calculated unadjusted univariate associations between delivery mode and caries, which was an oversimplification taking the complex aetiology of ECC into account (Kirthiga et al. 2019). Some of the included studies used a blend of confounding factors to adjust the multivariate analyses concerning caries background variables, but we decided to extract the crude dichotomised data to be able to pool the outcome. Reporting a standardized “core outcome set” at a certain age in future projects would certainly facilitate the compilation of data and increase the certainty of evidence in tomorrow’s systematic reviews. Still, the results of present study indicate that the mode of childbirth delivery should be captured and a possible risk factor for ECC.

The authors found high heterogeneity between the included studies, reflecting variations in population size, study group characteristics, outcome age, methods for caries detection and disease rate. The registry-based studies profited from their large sizes, but suffered from weak reliability in the outcome assessment, while a weakness in many cross-sectional trials was the representability of the selected study populations. We are confident that the “exposure” data were reliable although this information in some studies was collected from retrospective questionnaires completed by custodians. A limitation was, however, that all publications lacked detailed information on the reason for the C-section and if it was conducted on maternal request, medical indications or emergencies. Only the registry based study by Brandquist et al. (2017) defined the exposure criteria as “delivery starts by caesarean section” and included both elective and emergency cases. This lack of information may have an impact on the results, since the sociodemographic variables, health beliefs and level of economic development of the societies are important factors and co-variates that can affect both the rate of C-section and the occurrence of caries (Pitts et al. 2017; Jadoon et al. 2019).

The data on the “outcome” were in most studies based on clinical scoring of decayed, extracted and filled teeth on cavity level and this was likely robust enough for the dichotomous outcome measure used here. However, caries is a continuum and cavities takes often years to develop and only one trial included detection of the early, non-cavitated stages of the disease and used bitewing radiographs to detect proximal lesions (Boustedt et al. 2018). This means that the true prevalence of caries was certainly underestimated as the early carious lesions makes up the greater share at all preschool ages, particularly in industrialised countries (André Kramer et al. 2014). The contrasting levels of ECC across the accepted studies should also be noted; the caries prevalence at 3 years of age on cavitated level (deft > 0) was very low (< 9%) in all the Scandinavian studies, while the prevalence was 3–5 times higher in the non-Nordic reports. Also the caries frequency, expressed as mean deft, differed five–tenfold across the publications. These large differences in the event rate, likely mirroring the public dental health structures, access to dental care and community-based preventive measures in the different countries, contribute to the high heterogeneity disclosed here. Another shortcoming was that only two studies reported data from calibration and reliability tests of the examiner(s).

Conclusion

Within the limitations of this systematic review, we found a weak trend but no firm association between the mode of delivery and the prevalence of early childhood caries. There was an obvious inconsistency and heterogeneity across the included studies but the findings indicate that the mode of delivery should be registered in the paediatric dental records. Further studies based on representative birth cohorts and reporting a standardized core outcome set are warranted to answer the research question with higher certainty.

References

André Kramer AC, Skeie MS, Skaare AB, Espelid I, Östberg AL. Caries increment in primary teeth from 3 to 6 years of age: a longitudinal study in Swedish children. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2014;15:167–73.

Anil S, Anand PS. Early childhood caries: prevalence, risk factors, and prevention. Front Pediatr. 2017;5:157.

Antão C, Teixeira C, Gomes MJ. Effect of mode of delivery on early oral colonization and childhood dental caries: a systematic review. Port J Public Health. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1159/000495804.

Bäckhed F, Roswall J, Peng Y, Feng Q, Jia H, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Li Y, Xia Y, Xie H, Zhong H, Khan MT, Zhang J, Li J, Xiao L, Al-Aama J, Zhang D, Lee YS, Kotowska D, Colding C, Tremaroli V, Yin Y, Bergman S, Xu X, Madsen L, Kristiansen K, Dahlgren J, Wang J. Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the first year of life. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:852.

Barfod MN, Christensen LB, Twetman S, Lexner MO. Caries prevalence in Danish pre-school children delivered vaginally and by caesarean section. Acta Odontol Scand. 2012;70:190–3.

Begum T, Saif-Ur-Rahman KM, Yaqoot F, Stekelenburg J, Anuradha S, Biswas T, Doi SA, Mamun AA. Global incidence of Caesarean deliveries on maternal request: a systematic review and meta-regression. BJOG. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16491.

Boustedt K, Roswall J, Dahlén G, Dahlgren J, Twetman S. Salivary microflora and mode of delivery: a prospective case control study. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15(1):155.

Boustedt K, Roswall J, Twetman S, Dahlgren J. Influence of mode of delivery, family and nursing determinants on early childhood caries development: a prospective cohort study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2018;76:595–9.

Boustedt K, Roswall J, Kjellberg E, Twetman S, Dahlgren J. A prospective study of perinatal and metabolic risk factors for early childhood caries. Acta Paediatr. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15424.

Brandquist E, Dahllöf G, Hjern A, Julihn A. Caesarean section does not increase the risk of caries in Swedish children. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2017;2:386–96.

Dzidic M, Collado MC, Abrahamsson T, Artacho A, Stensson M, Jenmalm MC, Mira A. Oral microbiome development during childhood: an ecological succession influenced by postnatal factors and associated with tooth decay. ISME J. 2018;12:2292–306.

García-Castro LS, Perona-Miguel de Priego G. Association between the mode of delivery and the occurance of early childhood caries in children from 2 to 5 years of the maternal childhood center Pachacutec Perú-Korea, Diresa Callao, Perú 2016. Odontol Pediatr. 2017;16:30–40.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Sultan S, Glasziou P, Akl EA, Alonso-Coello P, Atkins D, Kunz R, Brozek J, Montori V, Jaeschke R, Rind D, Dahm P, Meerpohl J, Vist G, Berliner E, Norris S, Falck-Ytter Y, Murad MH, Schünemann HJ, GRADE Working Group. GRADE guidelines: 9. Rating up the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:1311–6.

Jadoon B, Mahaini R, Gholbzouri K. Determinants of over and underuse of caesarean births in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: an updated review. East Mediterr Health J. 2019;25:837–46.

Keag OE, Norman JE, Stock SJ. Long-term risks and benefits associated with cesarean delivery for mother, baby, and subsequent pregnancies: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2018;15(1):e1002494.

Kirthiga M, Murugan M, Saikia A, Kirubakaran R. Risk factors for early childhood caries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case control and cohort studies. Pediatr Dent. 2019;41:95–112.

Korolenkova MV, Khachatryan AG, Arutyunyan LK, Gadzhikulieva KA. Perinatal risk factors of the early childhood caries. Stomatologiia (Mosk). 2020;99:47–51.

Li H, Wang J, Wu L, Luo J, Liang X, Xiao B, Zhu Y. The impacts of delivery mode on infant’s oral microflora. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11938.

Marcenes W, Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Flaxman A, Naghavi M, Lopez A, Murray CJ. Global burden of oral conditions in 1990–2010: a systematic analysis. J Dent Res. 2013;92:592–7.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–12.

Nakai Y, Mori Y, Tamaoka I. Antenatal health care and postnatal dental check-ups prevent early childhood caries. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2016;240:303–8.

Nelun Barfod M, Magnusson K, Lexner MO, Blomqvist S, Dahlén G, Twetman S. Oral microflora in infants delivered vaginally and by caesarean section. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2011;21:401–6.

Occhi-Alexandre IGP, Cruz PV, Bendo CB, Paiva SM, Pordeus IA, Martins CC. Prevalence of dental caries in preschool children born preterm and/or with low birth weight: a systematic review with meta-analysis of prevalence data. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2020;30:265–75.

Pattanaporn K, Saraithong P, Khongkhunthian S, Aleksejuniene J, Laohapensang P, Chhun N, Chen Z, Li Y. Mode of delivery, mutans streptococci colonization, and early childhood caries in three- to five-year-old Thai children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2013;41:212–23.

Peretz B, Kafka I. Baby bottle tooth decay and complications during pregnancy and delivery. Pediatr Dent. 1997;19:34–6.

Pitts NB, Zero DT, Marsh PD, Ekstrand K, Weintraub JA, Ramos-Gomez F, Tagami J, Twetman S, Tsakos G, Ismail A. Dental caries. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17030.

Shanthosh Raj S, Moses J, Gayathri K, Vignesh KC, Irfana A. Prevalence of early childhood caries in correlation with the mode of delivery of 8–72 months old vhilden in Mogappair—a cross-sectional study. Int J Curr Res. 2018;10:68121–5.

Sridevi T, Pranoti S, Anand S, Umesh W, Sachin G. Factors associated with early childhood caries among 3 to 6 year old children in India: a case control study. J Neonatal Perinatal Med. 2018;11:45–50.

Tinanoff N, Baez RJ, Diaz Guillory C, Donly KJ, Feldens CA, McGrath C, Phantumvanit P, Pitts NB, Seow WK, Sharkov N, Songpaisan Y, Twetman S. Early childhood caries epidemiology, aetiology, risk assessment, societal burden, management, education, and policy: global perspective. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2019;29:238–48.

Twetman S, Boustedt K, Roswall J, Dahlgren J. Systematic review suggests a relationship between moderate to late preterm birth and early childhood caries. Acta Paediatr. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15424.

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. 2014. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm. (cited Feb 26, 2020).

Zhou Y, Lin HC, Lo ECM, Wong MCM. Risk indicators for early childhood caries in 2-year-old children in southern China. Aust Dent J. 2011;56:33–9.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg. The study was financed by the author’s institutions and did not receive any external funding. Funding has been received from Region Halland, University of Gothenburg, University of Copenhagen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors were involved in designing, analysing and drafting of the manuscript. ST and KB conducted the search, selection, data extraction and quality assessment. All authors contributed to, and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boustedt, K., Dahlgren, J., Roswall, J. et al. Is the mode of childbirth delivery linked to the prevalence of early childhood caries? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 22, 765–772 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40368-021-00621-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40368-021-00621-6