Abstract

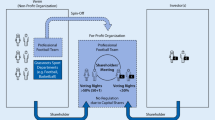

Trading football players is a massive, global business where several single trades have brought in more than $100 million in transfer fees. This has brought about a business practice where third-party investors provide or receive a share of the transfer fees, so-called third-party ownership. However, effective May 1, 2015, Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) has imposed a worldwide ban on this practice. In the face of already-initiated legal challenges, this article considers whether the ban is compatible with European Union law. It finds that the ban violates both free movement rights and competition law and that FIFA would be well served to consider a less-restrictive measure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Fédération Internationale de Football Association.

The sport that some refer to as “soccer.”

See further infra Part 3.

According to FIFA, a third party is “a party other than the two clubs transferring a player from one to the other, or any previous club, with which the player has been registered.” RSTP, definitions.

See also Abatan (2012), p. 22 (defining TPO as “the partial or total ownership of ‘economic rights’ of a player by a third party (i.e., an entity which is not a club), which, in the event of a future transfer, entitles such third party to receive a share”).

Mirror (2011).

ESPN (2015).

Borden (2015).

Liga Nacional de Fútbal Profesional.

Liga Portuguesa de Futebol Profissional.

Associated Press, Spain, Portugal against FIFA ban of third-party ownership, February 11, 2015.

Cf. KEA-CDES Report (2013), p. 6.

Thus, the ownership part of TPO refers not to the player as such but to future transfer fees for the player.

KPMG Report (2013), pp. 37–38.

Id. p. 13.

CIES Report (2013), p. 10.

KPMG Report (2013), pp. 37–38.

Ibid.

See, e.g., CAS 2004/A/701, Sport Club Internacional.

CAS 2004/A/635, RCD Espanyol; CAS 2004/A/701, Sport Club Internacional; CAS 2004/A/662, RCD Mallorca; CAS 2007/O/1391, Play International.

See further infra Part 5.

Aho (2011).

FIFA, Circular no. 1464.

RSTP, Article 3.1.a.

Premier League Rules, Season 2014/15, Rules U39–U40.

Case 36/74, Walrave v. Union Cycliste Internationale, EU:C:1974:140, para 4; Case 13/76, Donà v. Mantero, EU:C:1976:115, para 12; C-415/93, URBSFA v. Bosman et al., EU:C:1995:463, para 73; Cases C-51/96 and C-191/97, Deliége v. Ligue Francophone de judo et disciplines associées ASBL, EU:C:2000:199, para 41; Case C-176/96, Lehtonen v. Fédération royale belge des sociétés de basket-ball ASBL, EU:C:2000:201, para 32; Case C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina and Majcen v. Commission, EU:C:2006:492, para 22; Case C-325/08, Olympique Lyonnais SASP v. Bernard and Newcastle UFC, EU:C:2010:143, para 27.

Commission, The EU and Sport, Annex I, sec 1.

See, e.g., KEA-CDES Report (2013), pp. 91–92.

The Commission singles out “[r]ules regulating the transfer of athletes between clubs (except transfer windows)” as a type rule that “represent a higher likelihood of problems concerning compliance with Articles [101 TFEU] and/or [102 TFEU].” Commission, The EU and Sport, sec 3.4.

It has been suggested that the TPO ban could also constitute an obstacle to the free movement of workers. The reduction of capital available for player acquisition could effect player movement. Cf. Lindholm (2011), pp. 201–203. However, such a claim would essentially overlap with the claim under free movement of capital and the restriction is more remote.

Free movement of goods, workers, services, and capital.

See Flynn (2014), pp. 444–447.

Presented supra Part 1.

Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 of 16 December 2002 on the implementation of the rules on competition laid down in Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty, OJ L 1, 4.1.2003, pp. 1–25.

See, e.g., Joined cases C-163/94, C-165/94 and C-250/94, Criminal Proceedings against Sanz de Lera et al. EU:C:1995:451; Case C-57/95, France v. Commission, EU:C:1997:164, para 20.

Flynn (2014), p. 453.

Case 36/74, Walrave v. Union Cycliste Internationale, EU:C:1974:140, paras 18–19. The Walrave Court emphasized that the prohibition of discriminatory actions. However, in subsequent decisions the CJEU extended the same reasoning to non-discriminatory obstacles to free movement. See, e.g., Case C-415/93, URBSFA v. Bosman et al. EU:C:1995:463, paras 83–84; Case C-341/05, Laval un Partneri Ltd v. Svenska Byggnadsarbetareförbundet et al., EU:C:2007:809, para 98.

See, e.g., Case C-415/93, URBSFA v. Bosman et al., EU:C:1995:463; Case C-341/05, Laval un Partneri Ltd v. Svenska Byggnadsarbetareförbundet et al., EU:C:2007:809.

See, however, Case C-171/11, Fra.bo SpA v. DVGW, EU:C:2012:453 (a private entity was allowed to invoke the free movement of goods against another private entity that in practice governed market access).

This becomes clearer if we imagine an even more extreme scenario. Imagine, for example, that a private stock exchange that dominates the financial market of a Member State refused access to investors from other Member States. It seems entirely improbable that an excluded Article 63 TFEU could not be invoked against the stock exchange.

Council Directive 88/361/EEC of 24 June 1988 for the implementation of Article 67 of the Treaty, Annex I.

Id.

See, e.g., Case C-478/98, Commission v. Belgium, EU:C:2000:497, para 27.

Commission, EU and Sport, Annex I, sec 2.1.4.

Case C-41/90, Höfner and Elser v. Macrotron GmbH, EU:C:1991:161, para 21.

See Case T-193/02, Piau v. Commission, EU:T:2005:22; Case C-49/07, Motosykletistiki Omospondia Ellados NPID (MOTOE) v. Elliniko Dimosio, EU:C:2008:376. See also infra Part 4.4.

Cf. Case T-193/02, Piau v. Commission, EU:T:2005:22; Smith and Hornsby (2015).

The player market includes the player transfer market for players that are under contract.

See Egger and Stix-Hackl (2002).

The TPO ban’s effect is in this regard similar to that of UEFA’s Financial Fair Play rules. See Lindholm (2011), pp. 195–196.

See further infra Part 5.5.

Some anti-competitive agreements or decisions may however fall outside Article 101’s scope. See further infra Part 5.1.

Case C-171/05 P, Piau v. Commission, EU:C:2006:149.

Case T-193/02, Piau v. Commission, EU:T:2005:22, paras 107–16.

Id. at para 117.

Case 85/76, Hoffmann-La Roche & Co. AG v Commission, EU:C:1979:36, para 91.

Case C-367/98, Commission v. Portugal, EU:C:2002:326, para 49 (referring to these legitimate aims as “overriding requirements of the general interest”).

Case C-55/94, Gebhard v. Consiglio dell'Ordine degli Avvocati e Procuratori di Milano, EU:C:1995:411, para 37.

Case C-415/93, URBSFA v. Bosman et al., EU:C:1995:463, para 104.

Case C-309/99, Wouters et al. v. Algemene Raad van de Nederlandse Orde van Advocaten, EU:C:2002:98, para 97.

Case C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina & Majcen v. Commission, EU:C:2006:492.

Jones and Sufrin (2011), pp. 376–382.

Conn (2014).

BBC News (2015).

FIFPro (2014).

Borden (2015).

UEFA president Michael Platini. BBC News (2015).

The only one that has any “rights to a player” is a football club that has signed a fixed-term contract with a player.

Cf. Crespo Pérez (2014).

Case C-519/04 P, Meca-Medina & Majcen v. Commission, EU:C:2006:492, para 43.

CAS 98/200, AEK Athens, para 113.

CIES Report 2013.

RSTP, Article 18ter, para 5.

Reck and Geey (2011).

Andrews and McDonald (2012), p. 16.

KEA-CDES Report (2013), p. 8.

Cf. Harris ( 2014).

Andrews and McDonald (2012), p. 16.

See, e.g., Case 352/85, Bond van Adverteerders v. Netherlands, EU:C:1988:196, para 34; Case C-398/95, Syndesmos ton en Elladi Touristikon kai Taxidiotikon Grafeion v. Ergasias, EU:C:1997:282, para 25.

Case C-325/08, Olympique Lyonnais SASP v. Bernard & Newcastle UFC, EU:C:2010:143, para 41. See also C-415/93, URBSFA v. Bosman et al. EU:C:1995:463, para 108.

CIES Report (2013), p. 10.

KEA-CDES Report (2013), p. 255.

Ross (2004), p. 50. As discussed above, this would also be in line with the moral argument. See supra Part 5.2.

Conn (2014).

FIFPro (2014).

UEFA Club Licensing and Financial Fair Play Regulations (2012)

See Lindholm (2011), pp. 195–196.

Abatan (2012), p. 30.

Hall et al. (2002).

See supra Part 1.

Lindholm (2011), pp. 205–208.

KPMG Report 2013, p. 16.

See id. p. 33 (explaining that TPO agreements in South America rarely contain minimum-return clauses).

Ferrari (2012), p. 66.

Cf. Carmichael and Thomas (1993), p. 1469.

Andrews and McDonald (2012), p. 16.

See Articles 20–21, 45 TFEU.

Joined Cases C-403/08 and 429/08, FA Premier League et al. v. QC Leisure et al. and Murphy v. Media Protection Services Ltd (“Murphy”), EU:C:2011:631.

Id. at para 139.

CDES report (2013), p. 8.

See, generally, Goodard (2006).

See supra Part 2.

SB Nation (2014).

CIES Report (2013), p. 19.

See supra Part 5.5.

Lombardi et al. (2014), p. 34.

See supra Part 5.4; Lindholm (2011), p. 210.

References

Abatan E (2012) An overview of third party ownership in European professional football. Sport Law Bull 10:22–32

Aho P (2011) Application of FIFA article 18bis: tampere united’s case. World Sports Law, Report 9

Andrews K, McDonald I (2012) Prohibition on third-party ownership: analysis. World Sports Law Rep 10:14–16

BBC News (2015) Third-party ownership called ‘a type of slavery’ by Michel Platini. March 16, 2015

Bird L (2014) FIFA’s third-party ownership crusade has major implications in S. America. Sports Illustrated. October 29, 2014

Borden S (2015) A contentious source of income is set to dry up. N.Y. Times. 1:2015

Carmichael F, Thomas D (1993) Bargaining in the transfer market: theory and evidence. Appl Econ 25:1467–1476

Commission (2007) The EU and sport: background and context, accompanying document to the white paper on sport. SEC(2007) 935. November 7, 2007 (”The EU and Sport”)

Conn D (2014) Why the premier league banned’third-party ownership’ of players. The guardian. January 30, 2014

Crespo Pérez J (2014) Third party player ownership (Tppo): a legitimate player financing mechanism requiring only “light-touch” regulation; or a threat to the integrity of sporting competition which must be legislated out of existence?. November, 10, 2014. http://www.sportbusinesscentre.com/events/third-party-player-ownership-tppo/. Accepted date March 16, 2015

Duarte F (2014) Fifa’s third-party ownership ban: is it good or bad news for Brazil? The Guardian. October 21, 2014

Egger A, Stix-Hackl C (2002) Sports and competition law: a never-ending story? Euro Compet Law Rev 23:81–91

ESPN (2015) Neymar commits to Santos. November 9, 2011. http://www.espnfc.com/story/981959/neymar-signs-new-contract-with-santos. Accepted date March 16, 2015

Ferrari L (2012) Some thoughts on third party ownership. Sports Law Bull 10:66–69

FIFPro (2014) FIFPro versus third party ownership. March 28, 2014. http://www.fifpro.org/en/news/fifpro-versus-third-party-ownership. Accepted date March 16, 2015

Flynn L (2014) Free movement of capital. In: Barnard C, Peers S (eds) European union law. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 443–472

Goodard J (2006) The economics of soccer. In: Andreff Wladimir, Szymanski Stefan (eds) Handbook on the economics of sport. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 451–458

Hall S et al (2002) Testing causality between team performance and payroll—the cases of major league baseball and English soccer. J Sports Econ 3:149–168

Harris W (2014) Has third party ownership found a back door into premier league?. Business of Soccer. May, 2014. http://www.businessofsoccer.com/2014/05/21/has-third-party-ownership-found-a-back-door-into-premier-league/. Accepted date March 16, 2015

International Centre for Sport Studies (2013) Third-party ownership of players’ economic rights (”CIES Report 2013”). http://www.futbalsfz.sk/fileadmin/user_upload/Legislativa/Medzinarodne_institucie/20140512_Third-party_Ownership_of_Players_Economic_Rights_01.pdf. Accepted date March 16, 2015

Jones A, Sufrin B (2011) EU competition law, 4th edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

KEA-CDES (2013) The economic and legal aspects of transfers of players (”KEA-CDES Report 2013”). http://ec.europa.eu/sport/library/documents/cons-study-transfers-final-rpt.pdf. Accepted March 16, 2015

KPMG (2013) Project TPO. August 8, 2013 (“KPMG Report 2013”). http://www.ecaeurope.com/Research/External%20Studies%20and%20Reports/KPMG%20TPO%20Report.pdf. Accepted date March 16, 2015

Levine A (1995) Hard cap or soft cap: the optimal player mobility restrictions for the professional sports league. Fordham Intellectl Prop Media Entertain Law J 6:243–299

Lindholm J (2011) The problem with salary caps under european union law: the case against financial fair play. Texas Rev Entertain Sports Law 12:189–213

Lombardi R et al (2014) Third party ownership in the field of professional football: a critical perspective. Bus Syst Rev 3:32–47

Mirror (2011) Santos president warns Real Madrid over Neymar deal. September 15, 2011

Reck A, Geey D (2011) Third-party ownership and UEFA’s FFPR: a premier league handicap. Sport EU Rev 3:6–12

Robalinho M (2013) Third-party ownership of football players: why are the big actors in the football market afraid? BookCountry 2013

Ross S (2004) Player restraints and competition law throughout the world. Marquette Sports Law Rev 15:49–61

SB Nation (2014) FIFA third-party ownership ban goes into effect May 1. December 19, 2014

Smith C, Hornsby S (2015) The FIFA ban on third party ownership and EU law. World Sports Law Report 13(3)

UEFA Club Licensing and Financial Fair Play Regulations (2012). http://www.uefa.org/MultimediaFiles/Download/Tech/uefaorg/General/01/80/54/10/1805410_DOWNLOAD.pdf. Accepted date March 16, 2015

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lindholm, J. Can I please have a slice of Ronaldo? The legality of FIFA’s ban on third-party ownership under European union law. Int Sports Law J 15, 137–148 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40318-015-0075-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40318-015-0075-7