Abstract

Objectives

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common and serious disorder with significant impact on patients and families. The goal of this retrospective cohort study was to determine the economic burden among patients with MDD stratified by number of treatment lines needed for episode resolution.

Methods

Truven Health Analytics MarketScan® claims data were used to identify US patients (≥ 18 years) who were diagnosed with MDD and started on an antidepressant between 2013 and 2017. A generalized linear model estimated direct and employment-related costs for the first 12 months following initiation of treatment across cohorts with increasing number of lines of MDD pharmacotherapy. Analyses were adjusted for demographics and clinical factors.

Results

A total of 73,597 patients with MDD comprising the commercial (n = 66,459) and Medicare (n = 7138) populations met selection criteria. Patients who completed treatment for their episode with a single line of antidepressant had the lowest total adjusted direct costs (commercial $9975; Medicare $14,628) followed by those who completed with two lines (commercial $11,723; Medicare $15,526) and those treated with three or more lines of antidepressant regimens (commercial $21,259; Medicare $20,964). Patients who completed treatment with two lines as opposed to one incurred significantly higher direct costs (commercial +$1748, p < 0.0001; Medicare +$898, p = 0.0092). Patients who completed treatment with one line had the lowest employment-related costs compared to other groups.

Conclusions

There was an increased economic burden associated with delay of episode resolution as early as the second line compared to the first line in MDD.

Similar content being viewed by others

This study focuses on the economic burden of incremental treatment in major depressive disorder (MDD) with a granular focus on early lines of pharmacotherapy treatment. |

Direct healthcare costs increase with a single failed antidepressant, highlighting the need for rapid and effective treatment options to achieve remission early after diagnosis. |

Employment-related costs and healthcare resource utilization also increase with the number of pharmacotherapy treatments needed for episode resolution. |

Early achievement of episode resolution may prevent higher total costs of care in patients with MDD. |

1 Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a brain health disorder that is characterized by distinct episodes of at least 2 weeks in duration and often associated with changes in affect, cognition, and function [1]. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) recommends treating MDD initially with psychotherapy and antidepressant medication [2]. An estimated 17 million adults in the United States experience at least one major depressive episode each year, of which approximately 7 million receive treatment with pharmacotherapy [3,4,5]. Antidepressants include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), and should be continued for at least 4 months after remission, for up to a lifetime depending on patient characteristics, according to the APA [2].

However, these existing antidepressant treatment options may be associated with delayed onset of response, low response and remission rates, and frequent presence of residual symptoms after remission [6,7,8,9,10]. Since antidepressants typically require 1–2 months from the start of treatment for effects to be realized [7, 8], this latency in response can lead to low adherence by patients, prolonged patient suffering, and increased healthcare resource utilization [6, 7, 11]. Current APA step pharmacotherapy protocols recommend modifying treatment if a patient fails to respond to first-line pharmacotherapy within 8 weeks [2]. However, remission is increasingly difficult to achieve after each treatment failure—approximately two-thirds of patients do not remit on first-line antidepressant, and remission rates decrease with each subsequent trial of antidepressant treatment [7].

Failure to treat MDD rapidly and effectively to remission may have long-term negative effects [7, 12,13,14,15,16], including lasting effects on patients’ brain structure and function [12, 15], longer depressive episodes and a higher likelihood of relapse [7, 13, 14], and worsened functional outcomes [16, 17]. There is mounting evidence that depression also takes a serious toll on physical health [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. MDD is significantly associated with increased incidence of many chronic disorders, such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease [30], Parkinson disease [31], cardiovascular disease [32], diabetes [33], obesity [34], autoimmune diseases [35], back pain and osteoarthritis [36, 37], hypertension [38], gastrointestinal ulcers [39], HIV/AIDS [40], asthma [39], and drug abuse [41]. In addition, depression can worsen the course of pre-existing comorbid conditions and may make chronic disease management more difficult [42,43,44,45,46,47]. These poor outcomes can often lead to higher patient costs associated with these chronic conditions in addition to the economic burden of MDD [18, 48].

MDD has significant impacts on healthcare resource utilization and total cost of care [3, 11, 48]. In 2010, the total incremental annual economic burden of individuals with MDD in the United States was estimated at over $200 billion [48]. Employed and treated MDD patients had elevated direct costs (both MDD and non-MDD related), incurring $5988 more than their matched non-MDD patients with similar demographics [48]. Previous studies have reported that delays in the treatment of MDD can also result in significantly higher costs of care [49]. Specifically, lack of treatment stability or pharmacotherapy cycling and switching has been associated with increases in total direct costs and depression-related direct and indirect costs [11, 14, 50]. In addition, substantial indirect costs, including decreased productivity due to illness, sickness absence from work, and early retirement, have been reported among MDD patients [48, 51, 52].

While the economic burden of treatment-resistant depression has been well studied [52,53,54,55,56,57], the direct and indirect financial impact of patients across increasing numbers of pharmacotherapy treatments in MDD has not been fully explored. Namely, the increased total costs associated with delayed episode resolution and the potential economic benefit of patients achieving early disease resolution within one pharmacotherapy treatment regimen have been overlooked. The goal of this retrospective cohort study was to evaluate the direct costs as well as employment-related costs and resource use among patients diagnosed and treated for a new MDD episode, stratified by the number of pharmacotherapy steps needed to meet episode resolution.

2 Methods

2.1 Data Source

In this retrospective cohort study, claims data from the Truven Health Analytics MarketScan® database were used. These databases contain individual-level healthcare claims information including, but not limited to, claims data, absence, short-term disability (STD), and workers’ compensation. The MarketScan Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits Database was used for the Medicare population with employer-sponsored Medicare Supplemental plans and contains mainly fee-for-service beneficiary data. The study was exempted from full review by the Western Institutional Review Board (Puyallup, WA) since it did not meet the definition of human subject research as per 45 Code of Federal Regulations 46.102.

2.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria and Cohort Classification

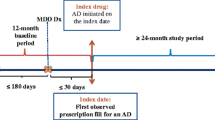

We assessed adult patients covered by either commercial or Medicare payers, diagnosed with MDD and started on antidepressant pharmacotherapy between January 1, 2013 and September 30, 2017. The index date was defined as the first documented prescription fill date for an antidepressant after the first MDD diagnosis.

Patients meeting the following criteria were included: 18 years or older as of the index date; at least one International Classification of Disease (ICD) claim for MDD in an inpatient or emergency room (ER) setting, or two ICD claims for MDD in an outpatient setting with at least one claim being within a 6-month period from index date (Supplemental Table 1, see the electronic supplementary material); one or more pharmacy claims for antidepressants (SSRIs, SNRIs, atypical antidepressants, TCAs, and MAOIs) anytime on the day of or after their first MDD diagnosis (Supplemental Table 1).

Patients were excluded based on the following: diagnosis codes for bipolar disorder or schizophrenia and/or prescriptions of lithium ≤ 6 months prior to the index date, which could indicate treatment for pre-existing bipolar or more treatment-experienced MDD; index treatment inconsistent with guideline-recommended first-line treatment (atypical antipsychotic, perphenazine, or a combination of two or more antidepressants). To ensure index treatment captured the start of pharmacotherapy treatment for a major depressive episode, patients were excluded if they had received antidepressants in the 6 months prior to the first index date. To ensure availability of a complete claims history, patients were required to have continuous enrollment or medical service for the 6 months prior to index and 12 months post index.

Treatment success was defined as completion of the minimum APA guideline-recommended duration of antidepressant therapy (8 weeks of pharmacotherapy in the acute phase followed by an additional 4–9 months continuation, i.e., a minimum of 25 weeks) with no further new antidepressants started after the continuation phase or claims with ICD codes indicative of continued depressive symptoms. Patients were stratified into four cohorts based on treatment patterns. The first two cohorts consisted of those who completed guideline-recommended treatment as defined above on their first antidepressant (index) and on their second antidepressant (one switch, completed guideline-recommended treatment duration and predefined success criteria on their second antidepressant). The third cohort consisted of patients who received three or more lines (two or more switches of antidepressant, treatment completion as predefined not required). Lastly, to capture the common issue of non-adherence to antidepressant pharmacotherapy, the fourth cohort included patients who discontinued their first or second antidepressant regimen prior to the guideline-recommended minimum treatment duration (< 25 weeks), without switching to a different antidepressant and with at least one additional MDD inpatient or outpatient claim after pharmacotherapy discontinuation, indicating that the patient was still suffering from a depressive episode.

2.3 Study Outcomes

The primary outcomes measured were direct costs for the first 12 months following initiation of antidepressants in each of the four treatment cohorts. Direct costs (total cost of care) were reported by setting (inpatient, outpatient, ER, and pharmacy) and diagnosis (MDD, other depression, non-depression). Direct costs were reported separately by payer type given underlying differences in baseline demographics and characteristics between the two populations.

Secondary outcomes included employment-related costs, number of days with a medical visit, and concomitant medication use. Employment-related costs included average workplace absence hours (total and due to sickness/disability) as well as STD days and payments, which were only available for a subset of commercial patients. Days with any type of medical visit were reported for the first 12 months following antidepressant initiation in each of the four treatment cohorts. The top concomitant medication groups, classified using the Veterans Affairs classification [58], were reported in each of the four treatment cohorts across three timeframes: 6 months prior to index to index date, index date to 6 months post index, and 6 months to 12 months post index.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

A generalized linear model (GLM) with a negative binomial distribution and log link function was used to model direct and employment-related costs for MDD patients stratified across the four treatment cohorts. Models were adjusted for baseline demographics/characteristics (age, gender, year, census regions, plan type, first MDD diagnosis setting) and the Charlson Comorbidity Index. All costs were adjusted to 2019 US dollars based on the Consumer Price Index [59]. Descriptive statistics were reported for days with a medical visit and concomitant medication use. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

3 Results

3.1 Study Cohort and Patient Characteristics

A total of 73,597 MDD patients comprising both the commercial payer (n = 66,459) and Medicare (n = 7138) populations met inclusion/exclusion and cohort definition criteria. A total of 26,965 patients completed guideline-recommended treatment on their first antidepressant, 3370 on their second antidepressant, and 23,209 after three or more antidepressant regimens, and 20,053 patients exhibited patterns of antidepressant non-adherence (Fig. 1).

Within each payer type, the four treatment cohorts were similar in baseline demographics and patient characteristics, with only minor differences between cohorts (Table 1). The majority of patients were female, comprising 68–69% of patients in the commercial population and 63–65% of patients in the Medicare population. The mean age ranged between 40 and 43 years in the commercial population and 75 and 76 years in the Medicare population. Region, plan types, and setting of first MDD diagnosis were consistent across cohorts.

3.2 Direct Costs in Commercial and Medicare Populations

Unadjusted, descriptive costs are shown in Table 2. After adjusting for demographics and the Charlson Comorbidity Index, trends of increasing direct costs with additional lines of therapy were similar across both payer types. Patients who completed treatment on their first antidepressant regimen had the lowest total direct costs (commercial $9975; Medicare $14,628), followed by patients who completed treatment on their second antidepressant regimen (commercial $11,723; Medicare $15,526), patients with non-adherence (commercial $13,015; Medicare $15,585), and finally patients receiving three or more antidepressant regimens (commercial $21,259; Medicare $20,964) (Table 3, Fig. 2).

Commercial patients who completed treatment on their second antidepressant reported significantly higher yearly adjusted direct costs than those who completed treatment with a single antidepressant (cost ratio 1.189, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.139–1.242, p < 0.0001). These patients incurred an additional $1748 in total adjusted healthcare costs. Differences in costs were explained by higher outpatient treatment costs (50% of cost differential) for both the treatment of MDD and of comorbidities, followed by inpatient costs (27%) and pharmaceutical costs (15%). ER costs accounted for 8% of the difference. Pharmacy costs for MDD treatment specifically (antidepressants) only accounted for 5% of the difference in total cost of care between groups (Table 3). Commercial patients who received three or more antidepressant regimens had a significantly larger total cost of care than patients who completed treatment on the first line of antidepressant (cost ratio 2.015, 95% CI 1.971–2.060, p < 0.0001), incurring an additional $11,285 in total adjusted healthcare costs. Differences in costs were driven by higher outpatient costs (47% of cost differential), inpatient costs (38%), pharmaceutical costs (10%), and ER costs (5%) for patients having undergone three or more treatments. Differences in pharmacy costs for MDD accounted for 1% of the cost differential. Commercial patients who were non-adherent also incurred increased costs compared to patients who completed treatment on their first-line antidepressant (cost ratio 1.230 95% CI 1.203–1.259, p < 0.0001); while costs of inpatient, outpatient, and ER care were higher in those who did not adhere, pharmacy costs were lower in the non-adherent group.

Similarly, in the Medicare patient population, patients who completed treatment on their second antidepressant incurred significantly higher costs than those who completed treatment on their first antidepressant (cost ratio 1.188, 95% CI 1.046–1.356, p = 0.0092). Medicare patients who received three or more lines of therapy also incurred significantly higher costs than single-line patients (cost ratio 1.685, 95% CI 1.582–1.795, p < 0.0001). Lastly, patients who were non-adherent to antidepressant therapy also incurred significantly higher total cost of care than patients who resolved on their first-line treatment (cost ratio 1.158, 95% CI 1.087–1.235, p < 0.0001). Detailed adjusted costs reported in Table 3b.

3.3 Employment-Related Costs in Commercial Population

Employment-related cost data were available for between 2.2% (absence) and 5.8% (STD) of commercial patients, with data unavailable (either due to lack of reporting, no information collected, or lack of value greater than zero) for the remaining commercial population. Among patients with reported absence and STD days, patients who completed treatment on the first antidepressant had the lowest adjusted employment-related costs (30 total days and 6 days due to sickness/disability for 2.1% of the cohort, 71 STD days and $9833 STD payment for 2.5% of the cohort), after adjustments for confounders (Table 4). Patients who completed treatment with two antidepressant regimens (35 total days and 7 days due to sickness/disability for 2.1% of the cohort, 84 STD days and $10,429 STD payment for 2.9% of the cohort) and those who were non-adherent to pharmacotherapy treatments (34 total days and 7 days due to sickness/disability for 2.5% of the cohort, 82 STD days and $10,676 STD payment for 8.5% of the cohort) followed, with comparable adjusted employment-related costs. Patients who received three or more antidepressant regimens had the highest number of adjusted workplace absence hours in the first 12 months from pharmacotherapy start (43 total days, 12 days due to sickness/disability, data reported for 2.1% of the cohort), STD days (123 days), and payments from STD ($14,604, for 7.6% of the cohort).

3.4 Days with Medical Visit

Descriptive statistics for the number of days with a medical visit are reported for both commercial and Medicare populations. Across both commercial patients and Medicare patients, those patients completing treatment with a single antidepressant had the lowest median days with a medical visit (commercial 13 days, Medicare 24 days), while those who received three or more antidepressant regimens had the highest median days (commercial 23 days, Medicare 37 days; Fig. 3). Patients completing treatment on second antidepressant regimens (commercial 16 days, Medicare 28 days) and non-adherent patients (commercial 16 days, Medicare 27 days) had a comparable number of days with a medical visit (Fig. 3).

Days with medical visit in a commercial and b Medicare populations during first 12 months after treatment initiation. Patients receiving three or more pharmacotherapy regimens had the highest number of median medical visit days, whereas those who completed treatment with one antidepressant had the lowest median medical visit days. This trend is seen in both the commercial and Medicare populations

3.5 Concomitant Medications

Within the commercial population, the most commonly prescribed concomitant medications were benzodiazepine derivative sedatives or hypnotics (10–43% of patients), followed by opioid analgesics (10–29% of patients), across all four cohorts and observed timeframes (Fig. 4). Other common medications in the commercial population included non-salicylate non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or antirheumatics, gastric medications, glucocorticoids, and systemic contraceptives. Within the Medicare population, the most common concomitant medications were antilipemic agents (26–59% of patients) across all four cohorts and timeframes (Fig. 5). Other common concomitant medications in the Medicare population were beta blockers, opioid analgesics, and gastric medications. Across both payer types, patients who received three or more antidepressant regimens were more frequently prescribed benzodiazepine derivative sedatives or hypnotics, and antipsychotics compared to patients completing treatment with one or two antidepressant regimens (Figs. 4 and 5).

4 Discussion

Current standard of care in depression treatment involves sequential step pharmacotherapy. If patients fail to respond sufficiently to the initial pharmacotherapy in 8 weeks, current APA guidelines recommend a change in treatment plan to another antidepressant [2], which can often lead to a cycle of repeated switching of pharmacotherapy treatments in an attempt to achieve remission [7]. This pattern can extend for many months, with patients receiving pharmacotherapy without symptom improvement and suffering functional impairment [7] and leads to higher costs associated with sequential step pharmacotherapy [60].

This retrospective cohort study demonstrated an incremental increase in direct costs, employment-related costs, and healthcare resource utilization with delays in achieving completion of guideline-recommended treatment of depressive episodes. Completion of the continuation phase of treatment (indicative of episode resolution in guidelines) on earlier lines of antidepressant therapy was associated with lower annual total cost of care when controlling for demographics and the presence of comorbidities. A consistent trend was observed across both Medicare and commercial populations, suggesting that the incremental economic burden exists regardless of payer type.

Prior analyses involving claims data reported healthcare cost differences between treatment-resistant and non-treatment-resistant depression patients ranging from $3042 to $6742 among commercial populations [52,53,54, 56, 57]. In our study, the adjusted difference in direct costs between patients who received three or more antidepressant regimens versus completing treatment with fewer antidepressant regimens ranged between $9537 and $11,285 in commercial patients. The high direct and employment-related costs observed in patients receiving three or more antidepressant regimens were comparable to those reported in other recent retrospective studies in treatment-resistant depression populations that are typically characterized by two or more failed antidepressant treatments [52,53,54,55,56,57]. While our study proxied patients achieving episode resolution using prescription treatment patterns, these ranges are aligned with previously observed costs in broader MDD and treatment-resistant depression patient cohorts [52,53,54, 56, 57].

Prior studies have also reported increased costs associated with delayed antidepressant therapy initiation and treatment switching [11, 49] and suggest step pharmacotherapy protocols may unintentionally result in increased medical costs—including inpatient and outpatient costs [60]. This is the first study with a novel granular focus on early lines of pharmacotherapy treatment, and the results of these analyses indicate that patients may accrue additional costs as they cycle through an increasing number of pharmacotherapy regimens. Specifically, significant differences in direct costs and substantial differences in employment-related costs and healthcare resource utilization were observed even between patients who completed treatment within one or two lines of antidepressant therapy. These findings suggest that delays in disease resolution involving even a single treatment change can be associated with an increased economic burden for MDD patients.

This economic burden of MDD extends well beyond the cost of antidepressant pharmacotherapy [61,62,63,64]. Our analysis found that pharmacy costs on average comprised only 3–18% of the cost directly attributable to MDD in commercial patients. Previous studies have corroborated this observation, estimating that around 40% of MDD direct costs were pharmacy related and that prescription drug spending for MDD only made up about 9% of total cost of care [48], with an average annual expenditure ranging from $603 to $955 for MDD pharmacotherapy [3, 48]. Therefore, faster achievement of guideline-recommended treatment may help lower direct costs overall.

While there are clear benefits to early episode resolution, identifying the best initial pharmacotherapy option for each MDD patient remains a major challenge [11, 65] since remission with the first pharmacotherapy treatment is difficult to achieve with current treatment options [7, 8]. Approximately two-thirds of patients do not achieve full symptom resolution on their first antidepressant pharmacotherapy [7, 66]. In addition, approaches to selecting an effective second pharmacotherapy are often inconsistent, due to considerations of safety and tolerability [67] and the limited efficacy superiority of any specific antidepressants over others [6, 65]. Therefore, a substantial unmet need exists for more rapid and effective pharmacotherapy options that promote treatment response and remission within an early line of pharmacotherapy after diagnosis.

There are several wider limitations in this study due to the inherent nature of claims analyses, including the inability to control for certain unknowns such as disease severity. Differences in health risk, such as MDD episode severity, number of prior episodes, and other underlying health conditions that may be more likely in patients on more lines of pharmacotherapy, are not captured by the claims data, but this analysis did control for baseline demographics/characteristics (age, gender, year, census regions, plan type, setting of first MDD diagnosis) and the Charlson Comorbidity Index. The use of the negative binomial distribution rather than using a continuous gamma distribution was due to the latter requiring positive values. As the two models demonstrate consistency in analyzing cost data (Supplemental Table 2, see the electronic supplementary material) [68], the negative binomial distribution was chosen to accommodate zero costs, which were observed in the 12 cost categories for some patients.

Furthermore, claims data rely on accurate coding and diagnoses [69]. In the Truven Health Analytics MarketScan® databases, commercial and Medicare costs are reported only for the employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) population, and thus are not representative of the general commercial and Medicare populations; however, this group represents a large market share of healthcare services, drugs, and medical devices. Since both the Medicare-paid amounts and the employer-paid supplemental insurance amounts are included in the database, only plans for which both the Medicare-paid amounts and the employer-paid amounts were available and evident on the claims were included. The claims data also do not capture the use of over-the-counter medications and other self-management techniques.

Since true clinical resolution is difficult to assess from claims data, completion of the guideline-recommended treatment continuation phase was used as a proxy for episode resolution. Employment-related costs were only examined in the commercial population as it was not available for the Medicare population. Long-term disability days and payments were not reported as they were not well represented in the dataset. Other factors not available in claims data could not be controlled for.

Additionally, there were limitations associated with the study design. This study examined costs and resource use among only commercial and Medicare populations, and reported results separately for each payer type given the differences between the two populations. Other payer types, such as Medicaid or patients covered by both commercial payers and Medicare, were not studied. Finally, this study is inherently limited due to its retrospective observational nature, and although key confounders were adjusted for, this study is subject to residual confounding and reporting bias due to the available information in the database.

5 Conclusions

The association between increased number of treatment lines and increased total cost of care even between one and two lines of therapy highlights that there is an economic burden associated with a lack of early MDD episode resolution. These costs are not limited to MDD pharmacotherapy but also include inpatient and outpatient direct costs and employment-related costs. Early achievement of episode resolution may help avert higher total cost of care for patients with MDD. These results support the critical need for rapid and effective pharmacotherapy options for optimizing treatment stability early after MDD diagnosis.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). 5th ed. Washington DC: 2013.

Gelenberg A, Freeman M, Markowitz J, Rosenbaum J, Thase M, Trivedi M, et al. American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(Suppl. 10):9–118.

Hockenberry JM, Joski P, Yarbrough C, Druss BG. Trends in treatment and spending for patients receiving outpatient treatment of depression in the United States, 1998–2015. JAMA Psychiat. 2019;76(8):810–7.

12-month prevalence of DSM-IV/WMH-CIDI disorders by sex and cohort (n=9,282); updated data as of July 19, 2007. 2020. https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/NCS-R_12-month_Prevalence_Estimates.pdf. Accessed 4 May 2020.

US Census Bureau Population Division. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Single Year of Age and Sex for the United States: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2017. 2018. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk.

Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Focus. 2018;16(4):420–9.

Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Stewart JW, Warden D, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR* D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1905–17.

Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Warden D, Ritz L, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR* D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28–40.

Nierenberg AA. Residual symptoms in depression: prevalence and impact. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(11):e1480. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.13097tx1c.

Nierenberg AA, Husain MM, Trivedi MH, Fava M, Warden D, Wisniewski SR, et al. Residual symptoms after remission of major depressive disorder with citalopram and risk of relapse: a STAR*D report. Psychol Med. 2010;40(1):41–50. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291709006011.

Gauthier G, Guérin A, Zhdanava M, Jacobson W, Nomikos G, Merikle E, et al. Treatment patterns, healthcare resource utilization, and costs following first-line antidepressant treatment in major depressive disorder: a retrospective US claims database analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):222. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1385-0.

Oluboka OJ, Katzman MA, Habert J, McIntosh D, MacQueen GM, Milev RV, et al. Functional recovery in major depressive disorder: providing early optimal treatment for the individual patient. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;21(2):128–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyx081.

Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Lavori PW, Shea MT, et al. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(2):229–33.

Bukh JD, Bock C, Vinberg M, Kessing LV. The effect of prolonged duration of untreated depression on antidepressant treatment outcome. J Affect Disord. 2013;145(1):42–8.

Moylan S, Maes M, Wray NR, Berk M. The neuroprogressive nature of major depressive disorder: pathways to disease evolution and resistance, and therapeutic implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(5):595–606. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2012.33.

IsHak WW, James DM, Mirocha J, Youssef H, Tobia G, Pi S, et al. Patient-reported functioning in major depressive disorder. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2016;7(3):160–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2040622316639769.

Habert J, Katzman MA, Oluboka OJ, McIntyre RS, McIntosh D, MacQueen GM, et al. Functional recovery in major depressive disorder: focus on early optimized treatment. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016;18:5. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.15r01926.

Kessler RC. The costs of depression. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2012;35(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2011.11.005.

Alonso J, Vilagut G, Chatterji S, Heeringa S, Schoenbaum M, Üstün TB, et al. Including information about co-morbidity in estimates of disease burden: results from the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol Med. 2011;41(4):873–86.

Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(6):1069–78.

Buist-Bouwman M, de Graaf R, Vollebergh W, Ormel J. Comorbidity of physical and mental disorders and the effect on work-loss days. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;111(6):436–43.

Chapman DP, Perry GS, Strine TW. Peer reviewed: the vital link between chronic disease and depressive disorders. Prevent Chronic Dis. 2005;2:1.

Derogatis LR, Morrow GR, Fetting J, Penman D, Piasetsky S, Schmale AM, et al. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. JAMA. 1983;249(6):751–7.

Dohrenwend Bruce P, editor. Adversity, stress, and psychopathology. Oxford University Press; 1998.

Manuel D, Schultz S, Kopec J. Measuring the health burden of chronic disease and injury using health adjusted life expectancy and the Health Utilities Index. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56(11):843–50.

McWilliams LA, Cox BJ, Enns MW. Mood and anxiety disorders associated with chronic pain: an examination in a nationally representative sample. Pain. 2003;106(1–2):127–33.

Nemeroff CB, Musselman DL, Evans DL. Depression and cardiac disease. Depress Anxiety. 1998;8(S1):71–9.

Ortega AN, Feldman JM, Canino G, Steinman K, Alegría M. Co-occurrence of mental and physical illness in US Latinos. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41(12):927–34.

Wells KB, Golding JM, Burnam MA. Chronic medical conditions in a sample of the general population with anxiety, affective, and substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146(11):1440–6.

Diniz BS, Butters MA, Albert SM, Dew MA, Reynolds CF 3rd. Late-life depression and risk of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based cohort studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(5):329–35. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.112.118307.

Wang S, Mao S, Xiang D, Fang C. Association between depression and the subsequent risk of Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;86:186–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.05.025.

Van der Kooy K, van Hout H, Marwijk H, Marten H, Stehouwer C, Beekman A. Depression and the risk for cardiovascular diseases: systematic review and meta analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(7):613–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1723.

Mezuk B, Eaton WW, Albrecht S, Golden SH. Depression and type 2 diabetes over the lifespan: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(12):2383–90. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc08-0985.

de Wit L, Luppino F, van Straten A, Penninx B, Zitman F, Cuijpers P. Depression and obesity: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178(2):230–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.015.

Andersson NW, Gustafsson LN, Okkels N, Taha F, Cole SW, Munk-Jørgensen P, et al. Depression and the risk of autoimmune disease: a nationally representative, prospective longitudinal study. Psychol Med. 2015;45(16):3559–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291715001488.

Larson SL, Clark MR, Eaton WW. Depressive disorder as a long-term antecedent risk factor for incident back pain: a 13-year follow-up study from the Baltimore Epidemiological Catchment Area sample. Psychol Med. 2004;34(2):211–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291703001041.

Farmer A, Korszun A, Owen MJ, Craddock N, Jones L, Jones I, et al. Medical disorders in people with recurrent depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(5):351–5.

Meng L, Chen D, Yang Y, Zheng Y, Hui R. Depression increases the risk of hypertension incidence: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Hypertens. 2012;30(5):842–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835080b7.

Patten SB, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, Modgill G, Jetté N, Eliasziw M. Major depression as a risk factor for chronic disease incidence: longitudinal analyses in a general population cohort. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(5):407–13.

Prince JD, Walkup J, Akincigil A, Amin S, Crystal S. Serious mental illness and risk of new HIV/AIDS diagnoses: an analysis of Medicaid beneficiaries in eight states. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(10):1032–8.

Sintov ND, Kendler KS, Walsh D, Patterson DG, Prescott CA. Predictors of illicit substance dependence among individuals with alcohol dependence. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70(2):269–78. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2009.70.269.

Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):851–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61415-9.

Fan H, Yu W, Zhang Q, Cao H, Li J, Wang J, et al. Depression after heart failure and risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2014;63:36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.03.007.

Dirmaier J, Watzke B, Koch U, Schulz H, Lehnert H, Pieper L, et al. Diabetes in primary care: prospective associations between depression, nonadherence and glycemic control. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79(3):172–8. https://doi.org/10.1159/000296135.

Sawa M, Chan P, Donnelly M, McKenna M, Osaki Y, Kishimoto T, et al. A case–control study regarding relative factors for behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia at a Canadian regional long-term extended care facility: a preliminary report. Psychogeriatrics. 2014;14(1):25–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12035.

Holt RI, de Groot M, Golden SH. Diabetes and depression. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14(6):491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-014-0491-3.

Grenard JL, Munjas BA, Adams JL, Suttorp M, Maglione M, McGlynn EA, et al. Depression and medication adherence in the treatment of chronic diseases in the United States: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(10):1175–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1704-y.

Greenberg PE, Fournier A-A, Sisitsky T, Pike CT, Kessler RC. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(2):155–62.

McIntyre RS, Prieto R, Schepman P, Yeh Y-C, Boucher M, Shelbaya A, et al. Healthcare resource use and cost associated with timing of pharmacological treatment for major depressive disorder in the United States: a real-world study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(12):2169–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2019.1652053.

Birnbaum HG, Ben-Hamadi R, Greenberg PE, Hsieh M, Tang J, Reygrobellet C. Determinants of direct cost differences among US employees with major depressive disorders using antidepressants. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27(6):507–17. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200927060-00006.

von Knorring L, Åkerblad A-C, Bengtsson F, Carlsson Å, Ekselius L. Cost of depression: effect of adherence and treatment response. Eur Psychiatry. 2006;21(6):349–54.

Amos TB, Tandon N, Lefebvre P, Pilon D, Kamstra RL, Pivneva I, et al. Direct and indirect cost burden and change of employment status in treatment-resistant depression: a matched-cohort study using a US commercial claims database. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79:2.

Olchanski N, Myers MM, Halseth M, Cyr PL, Bockstedt L, Goss TF, et al. The economic burden of treatment-resistant depression. Clin Ther. 2013;35(4):512–22.

Sussman M, O’Sullivan AK, Shah A, Olfson M, Menzin J. Economic burden of treatment-resistant depression on the U.S. health care system. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(7):823–35. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2019.25.7.823.

Pilon D, Joshi K, Sheehan JJ, Zichlin ML, Zuckerman P, Lefebvre P, et al. Burden of treatment-resistant depression in Medicare: a retrospective claims database analysis. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:10.

Shrestha A, Roach M, Joshi K, Sheehan JJ, Goutam P, Everson K, et al. Incremental health care burden of treatment-resistant depression among Commercial, Medicaid, and Medicare payers. Psychiatric Serv. 2020;2020:201900398.

Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Kidolezi Y, Subramanian G, Khan SA, Stensland MD. Direct and indirect costs of employees with treatment-resistant and non-treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(10):2475–84. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007995.2010.517716.

US Department of Veterans Affairs. 2020. https://www.pbm.va.gov/nationalformulary.asp. Accessed 17 Apr 2020.

United States Bureau of Labor and Statistics. CPI inflation calculator. 2020. http://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm. Accessed 1 Feb 2020.

Mark TL, Gibson TM, McGuigan K, Chu BC. The effects of antidepressant step therapy protocols on pharmaceutical and medical utilization and expenditures. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(10):1202–9. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09060877.

Donohue JM, Berndt ER, Rosenthal M, Epstein AM, Frank RG. Effects of pharmaceutical promotion on adherence to the treatment guidelines for depression. Med Care. 2004;2004:1176–85.

Mojtabai R. Increase in antidepressant medication in the US adult population between 1990 and 2003. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(2):83–92.

Thorpe K, Hockenberry J. Prescription drugs and the slowdown in health care spending. Health Affairs Blog. 2015;2015:18.

Ventimiglia J, Kalali AH. Generic penetration in the retail antidepressant market. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(6):9.

Sinyor M, Schaffer A, Levitt A. The sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) trial: a review. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(3):126–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371005500303.

Papakostas GI. Managing partial response or nonresponse: switching, augmentation, and combination strategies for major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(Suppl 6):16–25. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.8133su1c.03.

Garcia-Toro M, Medina E, Galan JL, Gonzalez MA, Maurino J. Treatment patterns in major depressive disorder after an inadequate response to first-line antidepressant treatment. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):143. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-143.

Austin PC, Ghali WA, Tu JV. A comparison of several regression models for analysing cost of CABG surgery. Stat Med. 2003;22(17):2799–815. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1442.

Schneeweiss S, Avorn J. A review of uses of health care utilization databases for epidemiologic research on therapeutics. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(4):323–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.012.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Kathryn P. Wall at Boston Strategic Partners (supported by Sage Therapeutics, Inc.) for editorial support. During the peer review process, both Sage Therapeutics Inc. and their collaboration partner Biogen had the opportunity to review and comment on this manuscript; however, the authors had full editorial control of the manuscript and provided final approval on all content.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by Sage Therapeutics, Inc. and completed by Boston Strategic Partners (supported by Sage Therapeutics, Inc.).

Conflict of interest

Alix Arnaud and Ellison Suthoff are employees of Sage Therapeutics, Inc. with stock/stock options. Rita M. Tavares, Xuan Zhang and Aditi J. Ravindranath declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Truven Health Analytics MarketScan®, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and so are not publicly available.

Code Availability (software application or custom code)

Custom code can be made available from authors upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Analyses were performed by RMT, XZ, and AJR. The first draft of the manuscript was written by AJR, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arnaud, A., Suthoff, E., Tavares, R.M. et al. The Increasing Economic Burden with Additional Steps of Pharmacotherapy in Major Depressive Disorder. PharmacoEconomics 39, 691–706 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-021-01021-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-021-01021-w