Abstract

Background

Surgeons must discuss the most severe surgical complications with their patients while making a treatment decision. However, it is unclear which complications patients deem most severe. This study aimed to have patients classify potential complications following abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery based on severity using best–worst scaling.

Methods

Dutch patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm, either under surveillance or following surgery, received a survey with 33 potential surgical complications. The survey presented these complications in sets of three. Patients had to classify one of three complications as most severe and one as least severe. After all participants had completed the survey, the number of times a complication was classified as most severe was subtracted from the number of times that the complication was classified as least severe, thus resulting in a best–worse scaling score. Complications with the lowest scores were ranked as more severe.

Results

Fifty out of 79 participating patients completed the survey in full. Patients classified the following ten complications as most severe: Below-ankle amputation, aneurysm rupture, stroke, renal failure, type 1 endoleak, spinal cord ischaemia, peripheral bypass surgery, bowel lesion, myocardial infarction and heart failure. Haematoma was ranked as the least severe complication.

Conclusion

This best–worst scaling study enabled patients to classify complications following abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery based on severity. Vascular surgeons should discuss the ten complications deemed most severe with their patients and help their patients to effectively weigh the benefits of surgery against the harms patients themselves deem important, thereby improving shared decision making.

Plain Language Summary

Risks following surgery that are discussed with patients prior to surgery often differ per surgeon. By law, surgeons are required to discuss the most common and most severe complications that may occur following surgery with their patients. But what do patients actually consider to be the most severe complications? In this study, we have asked this question to 50 patients with a widened abdominal aorta. These patients were approached via the Dutch patient organisation for people with cardiovascular diseases (Harteraad) and the Amsterdam University Medical Centres. From previous research, we collected 33 complications that may occur following surgery of the abdominal aorta. Using a survey, participating patients were shown three complications at a time. Of these three complications, they had to indicate which complication they considered the most severe complication and which the least severe complication. After all participants had completed their survey, we looked at how often a complication was deemed most severe and least severe. The ten most severe complications according to the participating patients were forefoot amputation, rupture of the widened abdominal aorta, stroke, kidney failure, leakage of blood along the aortic prosthesis, not enough blood supply to the spinal cord or bowels, a narrowing of the arteries in the leg, a heart attack and heart failure. We recommend that vascular surgeons discuss these ten severe complications with their patient, when a decision must be made about whether or not that patient should undergo surgery for their widened abdominal aorta. This will allow patients to weigh the benefits of the surgery against the risks they themselves deem important.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Fifty patients ranked 33 potential complications following surgery of abdominal aortic aneurysms based on severity. |

Below-ankle amputation following a thromboembolic event was ranked as the most severe complication, followed by aneurysm rupture and stroke. |

Vascular surgeons should discuss the complications deemed most severe with their patients while making a decision about undergoing abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery. |

1 Introduction

Prior to surgery, vascular surgeons discuss the benefits and potential surgical complications with their patients. However, the complications patients are informed about often differ with each vascular surgeon [1, 2]. Surgeons are supposed to discuss the most frequently occurring complications and those major complications that a reasonable person in the patient’s position would deem of significance [3]. In a previous study, we reached consensus among vascular surgeons about major complications following abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) surgery [4]. However, it remains unclear which complications patients deem as most severe and would like to have discussed prior to surgery.

Understanding which complications following surgery patients deem most severe allows surgeons to obtain a true informed consent. It also ensures that all patients are informed in a similar manner regarding complications that are important to them. Patients will then be able to effectively weigh the benefits and harms of the available treatment options with their surgeon. Helping patients weigh the benefits and harms important to them is a crucial aspect of shared decision making [5]. Shared decision making between surgeons and patients has shown to improve patient satisfaction and quality of care, while also reducing overtreatment [5,6,7].

Weighing the benefits and harms of available treatment options is especially important for patients with an AAA. At some time during their disease progress, these patients may need to decide between continuing surveillance and undergoing endovascular or open surgery [8]. As patients with an AAA are usually asymptomatic and not every AAA will rupture, it continues to be difficult to predict which patients will benefit from surgery, that is, in which patients aneurysm rupture is prevented [9]. Thus, it is important for patients to understand that by undergoing surgery they may risk going from having no symptoms at diagnosis, to living with the consequences of a complication in order to reduce the risk of aneurysm rupture.

Therefore, this study aimed to have patients classify potential complications based on severity, to clarify the major complications patients want to be informed about prior to AAA surgery.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

The study design entailed a cross-sectional survey using best–worst scaling (BWS). Finn and Louviere first introduced BWS in the field of marketing research to elicit the preferences of participants [10]. They concluded that more information can be gained from having participants trade off one item against another than by asking participants to rate the importance of several items [11, 12]. The authors used the reporting guideline for survey research from Kelley et al. [13] to report this study (Appendix A, see electronic supplementary material).

2.2 Participants

Participants in this study were Dutch patients diagnosed with an AAA. These patients were either under surveillance or had already undergone endovascular or open surgery to treat their AAA. The researchers and patient partner identified potential participants via the Dutch patient organisation for people with cardiovascular diseases (Harteraad) and the outpatient clinic of the Amsterdam University Medical Centres—location Academic Medical Center. Members of the patient organisation, who were registered as having an AAA and at registration agreed to be open to participation in survey research, were invited by the patient partner to participate in the study. All consecutive patients who visited the outpatient clinic of the Amsterdam University Medical Centres—location Academic Medical Center between April 2018 and September 2018 for surveillance or follow-up of their AAA were invited by the researchers to participate in the study. If patients agreed to participate, they received the survey either electronically using Google forms (Mountain View, California, USA) or on paper, depending on the patients’ preference. A week after the survey was sent, one of the researchers would contact the patient via phone to see if further assistance was required to complete the survey. If assistance was required, the researcher would read aloud the survey to the participant and help them comprehend the complications presented in the survey. If patients had not returned the survey within 4 weeks after it had been sent, one of the researchers would contact the patient one last time to help patients complete the survey.

Calculating a sample size for a BWS study requires a significance level, a statistical power level, the statistical model and initial beliefs about parameter values [14]. No information or initial beliefs were present with regard to parameter values. In addition, we decided upon count analysis as the statistical model. This meant it was not possible to calculate a sample size, especially since the aim of our study was not to prove an effect or difference. Therefore, our sample was based on the expected availability and response rate of participants. A total of 140 patients were available between April 2018 and September 2018; 38 participants from the patient organisation and 100 participants from the outpatient clinic of the Amsterdam University Medical Centres—location Academic Medical Center. A response rate of 35% was expected based on previous literature for this combination of self-completion surveys and assistance via phone, resulting in a sample of 49 patients [13]. Thus, the researchers halted the search for new participants upon receiving 50 correctly filled-out surveys.

2.3 Survey Development

The survey used to elicit the opinion of patients with regard to the most severe complications following AAA surgery was developed for this specific research question. Development of this survey entailed the extraction and presentation of complications, the design of the survey and pilot testing.

2.4 Extraction of Complications

The complications presented in the survey included all complications discussed in reference articles of the Cochrane systematic review by Paravastu et al. [15]. Two researchers independently extracted 33 potential complications from these reference articles.

2.5 Presentation of Complications

The severity of complications may depend on their consequences. Therefore, the researchers provided each complication with a consequence of moderate severity based on the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) reporting standards [16]. For example, myocardial infarction may have a mild consequence if there are little or no hemodynamic consequences. It may have a moderate consequence if percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty is necessary. The complication becomes severe if resuscitation due to cardiac arrest occurs. To prevent bias, our survey presented patients with the moderate level of severity of each complication. Death was not included as a complication in the survey as the authors are of the opinion that the possibility of death following surgery must always be discussed with patients prior to surgery.

Vascular surgeons must discuss the most frequently occurring complications and the most severe complications with their patients. The most frequently occurring complications are usually those complications that occur in more than one out of 100 patients. These associated risks are fairly well known from local or international data sources. As stated, vascular surgeons must also discuss the most severe complications irrespective of their associated risks. Therefore, the researchers explicitly decided not to provide patients with the associated risks in our survey to assess their opinion about which actual complications patients deem most severe.

The survey presented the complications to patients using nonprofessional terms and also provided additional information about how these consequences would affect patients in their daily functioning. For example, a superficial wound infection would require patients to rinse the wound at home by themselves at least three times a day for about 3 weeks. Appendix B provides a complete description of complications used in this study (see electronic supplementary material).

2.6 Survey Design

The survey consisted of 15 questions. The first three questions concerned the patients’ sex, age and treatment status. Patients who had previously undergone endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR) or open surgery were also asked to fill out whether they had developed a specific complication following this surgery.

The 11 questions thereafter each presented three potential complications following AAA surgery. The researchers used the BWS case 1 design to present and analyse the relative importance of these complications [11]. For our survey, this meant that of the three complications presented per question, patients had to classify one complication as most severe and one complication as least severe. For each question, one complication was not classified as most severe or least severe—the classification box of this complication remained blank. Every patient received a different combination of three complications and a different order in which the survey presented the complications. The researchers used the ‘uniform division randomisation’ function in Microsoft Excel 2016 (Redmond, Washington, USA) to randomise the order in which the survey presented the complications. Each patient scored 33 complications.

The 15th and final question asked patients whether they missed any complications in the survey. An example of the survey used in this study is available in Appendix B (see electronic supplementary material).

The department of patient education at the Amsterdam University Medical Centres—location Academic Medical Centre ensured that the survey was designed and the questions were presented in a manner that participating patients would easily be able to understand.

2.7 Pilot Testing

Eight patients, who are members of a patient organisation, formed a workgroup to test the usability and readability of the survey. The electronic version and paper version were piloted separately in this workgroup upon request of the participants. All participants were able to fill out the questionnaire. However, some small adjustments to the cover letter were suggested to clarify the use of the survey. These changes were made accordingly.

2.8 Patient Partner

The patient partner, a representative of the Dutch patient organisation for people with cardiovascular diseases, played an important part in this study. The patient partner took part in designing the survey. In addition, the patient partner chaired the patients participating in the pilot study and actively reached out to other patients via the patient organisation to participate in the study. Finally, the patient partner critically reviewed the outcomes of the study.

2.9 Data Analysis

Patient demographics are summarised using descriptive statistics. Normally distributed outcome measures are expressed as means with standard deviations. Differences between participants and non-participants were studied using unpaired samples t tests and Chi-square analysis. Following the completion of 50 surveys, the researchers analysed the trade-offs between the complications in accordance with the BWS case 1 study design count analysis. This means that for each complication, the number of times patients classified it as most severe was subtracted from the number of times patients classified it as least severe. Since all 50 patients classified each of the 33 complications once, BWS scores could range between − 50 and 50. Complications with a BWS score close to − 50 were classified as the most severe complications (major), whereas complications with a BWS score close to 50 were classified as the least severe complications (minor). These results were presented in quantitative and narrative forms, including tables and figures, to aid in data presentation where appropriate.

2.10 Additional Analysis

The researchers also looked at whether the complications that were deemed most severe or least severe differed between patients with an AAA who were under surveillance, patients who had undergone EVAR and patients who had undergone open surgery. The researchers observed these potential differences by looking at the order in which these complications were ranked based on their BWS scores.

3 Results

3.1 Survey Responses

The researchers had sent the survey to 79 patients, before obtaining 50 correctly filled-out surveys (63% response rate). Forty-one patients were able to return the survey on their own. Nine patients required assistance via phone. Of the remaining 29 patients who did not return the survey, 11 patients had filled out the survey incorrectly. For example, they classified all three complications as most or least severe instead of just two out of the three complications presented per question. Four patients stated they found it difficult to classify complications they never had themselves and preferred not to participate. Five patients stated they did not have the time to complete the survey. Of the nine remaining patients, it was unclear as to why they refrained from filling out the survey, as they did not respond to follow-up inquiries.

3.2 Patient Demographics

Table 1 shows the demographics of the 50 participating patients. Forty-seven participants (94%) were men with a mean age of 72 years. Thirteen patients were (still) under surveillance. Of the 37 patients who had undergone surgery, 22 patients had undergone endovascular repair and 15 patients open surgery (41%). Eighteen patients reported they had suffered from complications following AAA surgery. Examples of these complications were wound infection, endoleaks, erectile dysfunction, renal insufficiency and ostomy dependency.

Table 1 also shows the patient demographics of patients who had not (correctly) filled out the survey. The researchers obtained the information on patient demographics from the survey itself. Nineteen out of 29 non-participants filled out this section of the questionnaire, which entailed all eleven patients who wrongly filled out the rest of the survey, all four patients who found it difficult to classify complications they never had themselves and four out of five patients who did not have time to complete the survey. This information could not be obtained from the nine patients who did not fill out the survey and could not be contacted thereafter. There were no statistically significant differences between the participants and non-participants based on our patient demographics.

3.3 Best–Worst Scaling

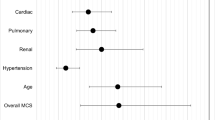

Figure 1 shows the BWS scores of all 33 complications based on the classifications made by the 50 participating patients. Sixteen of 33 complications received a negative score as these complications were more frequently considered most severe than least severe. Seventeen of 33 complications were more frequently considered least severe than most severe. Below-ankle amputation following a thromboembolic event was the highest ranking, most severe complication, with 43 of 50 patients (86%) considering this the most severe complication, followed by aneurysm rupture and stroke. Forty of 50 patients (80%) considered haematoma the least severe complication. Table 2 presents a detailed overview of the number of times patients classified a complication as most or least severe.

3.4 Additional Analysis

Figure 2 shows the BWS scores of all 33 complications stratified for the treatment patients had undergone. The order in which this figure presents the complications is similar to the order of presentation in Fig. 1. Since 13 patients were under surveillance, the BWS scores for this group ranged between − 13 and 13. Likewise, the endovascular repair group had a BWS range between − 22 and 22, and the open surgery group between − 15 and 15. Besides these smaller ranges for the surveillance and open surgery groups, no important differences in severity-based ranking were observed between the three treatment groups.

All three treatment groups reported amputation following a thromboembolic event, aneurysm rupture, stroke and renal failure requiring dialysis in their top-five ranking of most severe complications. These top-five rankings were completed by spinal cord ischaemia, bypass surgery following a thromboembolic event and type-1 endoleak requiring open surgery.

When looking at the top-five rankings of the least severe complications, all three groups reported haematoma, pseudoaneurysm and type-2 endoleak requiring follow-up. These top-five rankings were completed by erectile dysfunction, deep wound infection, superficial wound infection, urine retention, ureteral lesion and postoperative haemorrhage.

3.5 Missing Complications

One patient would like to have received information about the risk of developing a delirium following AAA surgery as an additional complication that had not been included in the survey.

4 Discussion

Using BWS, this study enabled patients to classify potential complications following AAA surgery, based on severity.

As mentioned in the introduction, our research group previously asked vascular surgeons to classify complications into major and minor complications [4]. Using a Delphi method [4], the vascular surgeons were able to reach consensus on 12 major complications. Their survey presented them with the same 33 complications as patients were shown in the present study. When comparing the top ten most severe complications as classified by patients with the 12 major complications acquired from vascular surgeons, nine complications are agreed upon. Table 3 shows these nine complications in alphabetical order. Other complications that vascular surgeons classified as major were allergic reaction, pulmonary embolus and vascular graft difficulties, such as graft infection and technical deployment problems. Vascular surgeons did not classify type-1 endoleak requiring open repair as a major complication. However, patients did classify this complication in their top ten most severe complications.

Vascular surgeons must discuss the most frequently occurring complications and the complications deemed most severe with patients. Thus, in addition to mentioning the most frequently occurring complications, we recommend that vascular surgeons discuss the ten most severe complications according to patients with their patients, albeit as worst-case scenarios, prior to making a decision between undergoing surgery and not (yet) undergoing surgery. This will allow patients to weigh the benefits of undergoing surgery against the harms they themselves deem of significance. Furthermore, vascular surgeons should help patients with this process and explicitly ask their patients about their preferences and concerns. Incorporating these preferences and concerns into the decision-making process makes it possible to reach a shared decision.

If patients cannot undergo open repair due to comorbidities or EVAR due to anatomical features, vascular surgeons obviously do not need to discuss the complications associated with the treatment that their patient cannot undergo. Nevertheless, it is important to inform patients about why they cannot undergo a specific treatment. This makes it easier for patients to accept the remaining options [17]. Vascular surgeons may even use the aforementioned complications to inform patients on why one of the treatment options is not feasible.

The first possible limitation of the study was to include patients both under surveillance and following surgery. The informed consent procedure states that the information provided should be relevant for patients in that particular situation in which a treatment decision needs to be made [3]. Thus, the researchers also included patients under surveillance, as they may face this decision in the future and can already start thinking about the information they would like to receive. Similarly, patients following surgery can reflect on the information they received and contemplate which information they deemed highly important or missed from the discussion with their vascular surgeon. However, as the researchers did not specifically ask patients in the surveillance group whether they were currently considering surgery, it is unclear whether our outcomes are compatible with patients who are facing this decision.

The second limitation concerns the patient sample included in this study. Due to the absence of a sample size calculation, the outcomes of this study were based on a sample size of 50 patients of 140 potential participants during the course of our study. It is unclear if a larger sample of patients would have led to a different list of most severe complications and whether these outcomes are representative of the larger population of patients with an AAA. However, there were no statistical differences in patient demographics between patients who did and did not (correctly) fill out the questionnaire nor were there any apparent differences between treatment groups in how complications were classified.

Third, the researchers used uniform division randomisation to randomise the order in which the complications were presented. Although this randomisation randomly paired all 33 complications in sets of three, some complications may have been paired together more often than with other complications. Thus, some trade-offs may have occurred more often than others.

Fourth, despite the fact that the researchers did perform pilot testing to ensure usability and readability of the newly designed survey, no psychometric testing was performed. It is unclear if patients would have filled out the survey exactly the same if they had to repeat the survey.

The fifth limitation concerns the information provided to patients. Some patients may find it difficult to comment on complications they themselves have not experienced. The researchers tried to assist patients in understanding what these complications would entail for patients by providing them with additional support and information explaining what the complications would mean for the patient in practical terms. Unfortunately, four patients still deemed it too difficult to comprehend the complications presented in the survey.

Finally, the survey presented patients with complications obtained from prior studies concerning AAA treatment. Unfortunately, patients did not partake in designing these studies, which means that outcomes that are relevant to patients may not have been included in these studies. For example, one patient found delirium to be missing from our list of complications. Thus, the authors recommend that researchers involve patients in the design process of new studies to ensure that patient-relevant outcomes are studied as well.

5 Conclusion

This study enabled patients to classify complications following AAA surgery based on severity. Vascular surgeons should discuss the top-ten most severe complications, as worst-case scenarios, with their patients, in addition to the most frequently occurring complications, while deciding between surgical options and conservative therapy. This will harmonise risk communication and improve shared decision making as it allows patients to effectively weigh the benefits of surgery against the harms patients themselves deem important.

Data Availability

There are no underlying data. The data collected to calculate best–worst scaling scores is provided in Table 2.

References

Knops AM, Ubbink DT, Legemate DA, de Haes JC, Goossens A. Information communicated with patients in decision making about their abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39:708–13.

McManus PL, Wheatley KE. Consent and complications: risk disclosure varies widely between individual surgeons. Ann R Coll Surg. 2003;85:79–82.

Sokol DK. Update on the UK law on consent. BMJ. 2015;350:h1481.

de Mik SML, Stubenrouch FE, Legemate DA, Balm R, Ubbink DT, DISCOVAR Study Group. Delphi Study to Reach International consensus among vascular surgeons on major arterial vascular surgical complications. World J Surg. 2019;43:2328–36.

Stiggelbout AM, Van der Weijden T, De Wit MP, Frosch D, Legare F, Montori VM, et al. Shared decision making: really putting patients at the centre of healthcare. BMJ. 2012;344:e256.

Stacey D, Legare F, Lewis K, Barry MJ, Bennett CL, Eden KB, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431.

Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: patients' preferences matter. BMJ. 2012;345:e6572.

Ubbink DT, Koelemay MJW. Shared decision making in vascular surgery. Why would you? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018;56:749–50.

Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, Ballard DJ, Jordan WD Jr, Blebea J, et al. Rupture rate of large abdominal aortic aneurysms in patients refusing or unfit for elective repair. JAMA. 2002;287:2968–72.

Finn A, Louviere J. Determining the appropriate response to evidence of public concern: the case of food safety. J Public Policy Mark. 1992;11:12–25.

Louviere J, Lings I, Islam T, Gudergan S, Flynn T. An introduction to the application of (case 1) best-worst scaling in marketing research. Int J Res Mark. 2013;30:292–303.

Yu T, Holbrook JT, Thorne JE, Flynn TN, Van Natta ML, Puhan MA. Outcome preferences in patients with noninfectious uveitis: results of a best-worst scaling study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:6864–72.

Kelley K, Clark B, Brown V, Sitzia J. Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15:261–6.

de Bekker-Grob EW, Donkers B, Jonker MF, Stolk EA. Sample size requirements for discrete-choice experiments in healthcare: a practical guide. Patient. 2015;8:373–84.

Paravastu SC, Jayarajasingam R, Cottam R, Palfreyman SJ, Michaels JA, Thomas SM. Endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014:CD004178.

Chaikof EL, Blankensteijn JD, Harris PL, White GH, Zarins CK, Bernhard VM, et al. Reporting standards for endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:1048–60.

Martin LR, Williams SL, Haskard KB, Dimatteo MR. The challenge of patient adherence. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2005;1:189–99.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SM, BR and AA contributed to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data and data analysis and interpretation. RB and DU contributed to the conception and design of the study and data analysis and interpretation. All authors were involved in drafting and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by the AMC Foundation, which was not involved in the study design, data analysis or interpretation of results.

Conflict of interest

Sylvana M.L. de Mik, Balou Rietveld, Annemarie Auwerda, Ron Balm and Dirk T. Ubbink have no conflicts of interest directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical approval

The Medical Ethics Review Committee of the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, confirmed that the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act does not apply to our study as it only required participants to fill out one questionnaire, limited in size, and the questions asked were not likely to cause any harm to the participants’ psychological integrity. Participants could decide on their own whether they wanted to fill out the questionnaire or not. All obtained participant data was stored anonymously. Thus, the participants were at no risks of potential harms and time spend on the survey by participants was deemed acceptably limited.

Additional information

Digital features

To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12624047.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Mik, S.M.L., Rietveld, B., Auwerda, A. et al. Best–Worst Scaling Study to Identify Complications Patients Want to Be Informed About Prior to Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Surgery. Patient 13, 699–707 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-020-00438-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-020-00438-3