Abstract

Introduction

Detecting signals of safety concerns associated with complementary medicines (CMs) relies on spontaneous reports submitted by health professionals and patients/consumers. Community pharmacists are well placed to identify and report suspected adverse drug reactions (ADRs) associated with CMs, but pharmacists submit few CMs ADR reports.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to explore New Zealand community pharmacists’ views and experiences with ADR reporting for CMs.

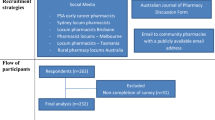

Methods

Qualitative, in-depth, semi-structured interviews were undertaken with 27 practising community pharmacists identified through purposive and convenience sampling. Data were analysed using a general inductive approach.

Results

Participants were familiar with systems for reporting ADRs, believed ADR reporting for CMs important, and that pharmacists should contribute. However, few submitted reports of CMs ADRs and none encouraged patients/consumers to do so. Participants explained this was because they had never been informed by patients about ADRs associated with CMs. Participants said they would report serious ADRs; time pressures, lack of certainty around causality, lack of awareness of mechanisms for reporting CMs ADRs, and lack of remuneration were deterrents to reporting. Participants were aware of intensive-monitoring studies for prescription medicines, understood the rationale for considering this approach for CMs and recognised there would be potential practical difficulties.

Conclusions

Participants used their knowledge of CMs safety concerns to minimise risk of harms to consumers from CMs use, but most had a passive approach to identifying and reporting ADRs for CMs. There is substantial potential for pharmacists to adopt proactive strategies in pharmacovigilance for CMs, particularly in recognising and reporting ADRs, and empowering CMs users to do the same.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Morgan TK, Williamson M, Pirotta M, Stewart K, Myers SP, Barnes J. A national census of medicines use: a 24-hour snapshot of Australians aged 50 years and older. Med J Aust. 2012;196(1):50–3.

Hunt KJ, Coelho HF, Wider B, Perry R, Hung SK, Terry R, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in England: results from a national survey. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(11):1496–502.

Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2015;79:1–16.

Steel A, McIntyre E, Harnett J, Foley H, Adams J, Sibbritt D, et al. Complementary medicine use in the Australian population: results of a nationally-representative cross-sectional survey. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):17325.

Smith T, Gillespie M, Eckl V, Knepper J, Reynolds CM. Herbal supplement sales in US increase by 9.4% in 2018. HerbalGram J Am Bot Counc. 2019;123:62–73.

World Health Organisation. WHO traditional medicine strategy: 2014–2023. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2013. https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/traditional/trm_strategy14_23/en/. Accessed 16 Mar 2020.

Ministry of Health. A Portrait of Health: key results of the 2006/07 New Zealand Health Survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health. http://www.health.govt.nz/publication/portrait-health-key-results-2006-07-new-zealand-health-survey. Accessed 25 February 2020.

University of Otago and Ministry of Health. A focus on nutrition: key findings from the 2008/09 NZ Adult Nutrition Survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2011. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/focus-nutrition-key-findings-2008-09-nz-adult-nutrition-survey. Accessed 16 Mar 2020.

Barnes J. Adverse drug reactions and pharmacovigilance of herbal medicines. In: Talbot J, Aronson J, editors. Stephens’ detection and evaluation of adverse drug reactions. 6th ed. Chichester: Wiley; 2012. p. 645–83.

Barnes J. Pharmacovigilance of herbal medicines: a UK perspective. Drug Saf. 2003;26(12):829–51.

Expert Committee on Complementary Medicines in the Health System. Complementary Medicines in the Health System, report to the Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Health and Ageing, Commonwealth of Australia (Sept 2003). Canberra. http://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/committees-eccmhs-report-031031.pdf. Accessed 24 Apr 2020.

Her Majesty the Queen: Natural Health Product Regulations. Can Gaz Part II. 2003;137(13):1562–607. Accessed 24 Apr 2020.

European Commission. Directive 2004/24/EC of the European parliament and of the council of 31 March 2004 amending, as regards traditional herbal medicinal products, Directive 2001/83/EC on the Community code relating to medicinal products for human use. Brussels: Official Journal of the European Union; 2004.

Dietary Supplement Regulations 1985 (SR 1985/208). Reprint as at 31 March 2010. . http://www.legislation.govt.nz/regulation/public/1985/0208/latest/DLM102109.html. Accessed 24 Apr 2020.

Food Act 1981. Reprint as at 24 June 2014. http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1981/0045/latest/DLM48687.html. Accessed 24 Apr 2020.

Barnes J, McLachlan AJ, Sherwin CMT, Enioutina EY. Herbal medicines: challenges in the modern world. Part 1. Australia and New Zealand. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2016;9(7):905–15.

CARM. New Zealand Pharmacovigilance Centre. https://nzphvc.otago.ac.nz/carm/. Accessed 24 Apr 2020.

New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority. https://medsafe.govt.nz/. Accessed 24 Apr 2020.

van Grootheest K, Olsson S, Couper M, de Jong-van den Berg L. Pharmacists’ role in reporting adverse drug reactions in an international perspective. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13(7):457–64.

Anon. Extension of the yellow card scheme to pharmacists. Curr Prob Pharmacovigil. 1997;23:3.

Anon. Updated yellow card launched. Pharm J. 2000;265:387.

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. The Yellow Card scheme: guidance for healthcare professionals, patients and the public. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/the-yellow-card-scheme-guidance-for-healthcare-professionals#what-to-report. Accessed 24 Apr 2020.

Barnes J, Tatley M. Scant reporting on CAMs safety in NZ. Pharmacy Today. 2007;February 6.

Davis S, Coulson R. Community pharmacist reporting of suspected ADRs: (1) the first year of the yellow card demonstration scheme. Pharm J. 1999;263:786–8.

Major E. The yellow card scheme and the role of pharmacists as reporters. Pharm J. 2002;269:25–6.

New Zealand Medicine and Medical Devices Safety Authority (MEDSAFE). Adverse reaction reporting—summary for 2010. Prescriber Update. 2011;32(1):7.

New Zealand Medicine and Medical Devices Safety Authority (MEDSAFE). Adverse reaction reporting in New Zealand—2015. Prescriber Update. 2016;37(1):2.

New Zealand Medicine and Medical Devices Safety Authority (MEDSAFE). Adverse reaction reporting in New Zealand——2019. Prescriber Update. 2020;41(1):8–9.

Farah MH, Edwards R, Lindquist M, Leon C, Shaw D. International monitoring of adverse health effects associated with herbal medicines. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2000;9(2):105–12.

Woo JJ. Adverse event monitoring and multivitamin–multimineral dietary supplements. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(1):323S–4S.

van Hunsel F, Skalli S, Barnes J. Consumers’ contributions to pharmacovigilance for herbal medicines: analyses of global reports in Vigibase. 18th ISoP annual meeting “pharmacovigilance without borders”, Geneva. Drug Saf. 2018;47(11):1218.

Hazell L, Shakir SA. Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2006;29(5):385–96.

Aronson J. Adverse drug reactions: history, terminology, classification, causality, frequency, preventability. In: Talbot J, Aronson J, editors. Stephens’ detection and evaluation of adverse drug reactions. 6th ed. Chichester: Wiley; 2011. p. 1–120.

Green CF, Mottram DR, Raval D, Proudlove C, Randall C. Community pharmacists’ attitudes to adverse drug reaction reporting. Int J Pharm Pract. 1999;7(2):92–9.

Van Grootheest AC, Mes K, de Jong-van den Berg LTW. Attitudes of community pharmacists in the Netherlands towards adverse drug reaction reporting. Int J Pharm Pract. 2002;10(4):267–72.

Wingfield J, Walmsley J, Norman C. What do Boots pharmacists know about yellow card reporting of adverse drug reactions? Pharm J. 2002;269:109–10.

Barnes J. An examination of the role of the pharmacist in the safe, effective and appropriate use of complementary medicines. PhD thesis, University of London; 2001.

Barnes J, Mills SY, Abbot NC, Willoughby M, Ernst E. Different standards for reporting ADRs to herbal remedies and conventional OTC medicines: face-to-face interviews with 515 users of herbal remedies. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;45(5):496–500.

Coulter DM. PEM in New Zealand. In: Mann R, Andrews E, editors. Pharmacovigilance. Chichester: Wiley; 2002. p. 345–62.

Pharmacy Council of New Zealand. Code of ethics. Wellington: Pharmacy Council of New Zealand; 2004.

Barnes J, Abbot NC. Professional practices and experiences with complementary medicines: a cross-sectional study involving community pharmacists in England. Int J Pharm Pract. 2007;15(3):167–75.

Barnes J, Dong C. Professional practices and experiences with complementary medicines: a cross-sectional study involving community pharmacists in New Zealand. 15th International social pharmacy workshop, 8–11 July 2008, Queenstown, New Zealand. Int J Pharm Pract. 2008;16(S2):B6–B7.

Bouldin AS, Smith MC, Garner DD, Szeinbach SL, Frate DA, Croom EM. Pharmacy and herbal medicine in the US. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(2):279–89.

Semple SJ, Hotham E, Rao D, Martin K, Smith CA, Bloustien GF. Community pharmacists in Australia: barriers to information provision on complementary and alternative medicines. Pharm World Sci. 2006;28(6):366–73.

Naidu S, Wilkinson JM, Simpson MD. Attitudes of Australian pharmacists toward complementary and alternative medicines. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39(9):1456–61.

Barnes J, Butler R. Community pharmacists’ views on the regulation of complementary medicines and complementary-medicines practitioners: a qualitative study in New Zealand. Int J Pharm Pract. 2018;26(6):485–93.

Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237–46.

Kanjanarach T, Krass I, Cumming RG. Exploratory study of factors influencing practice of pharmacists in Australia and Thailand with respect to dietary supplements and complementary medicines. Int J Pharm Pract. 2006;14(2):123–8.

Charrois TL, Hill RL, Vu D, Foster BC, Boon HS, Cramer K, et al. Community identification of natural health product-drug interactions. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(7):1124–9.

Walji R, Boon H, Barnes J, Welsh S, Austin Z, Baker GR. Reporting natural health product related adverse drug reactions: is it the pharmacist’s responsibility? Int J Pharm Pract. 2011;19(6):383–91.

Kheir N, Gad HY, Abu-Yousef SE. Pharmacists’ knowledge and attitudes about natural health products: a mixed-methods study. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2014;6:7–14.

Elkalmi RM, Hassali MA, Ibrahim MIM, Liau SY, Awaisu A. A qualitative study exploring barriers and facilitators for reporting of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) among community pharmacists in Malaysia. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2011;2(2):71–8.

Li R, Curtain C, Bereznicki L, Zaidi STR. Community pharmacists’ knowledge and perspectives of reporting adverse drug reactions in Australia: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40(4):878–89.

Mitchell AS, Henry DA, Sanson-Fisher R, O’Connell DL. Patients as a direct source of information on adverse drug reactions. BMJ. 1988;297(6653):891–3.

Medawar C, Herxheimer A, Bell A, Jofre S. Paroxetine, Panorama and user reporting of ADRs: Consumer intelligence matters in clinical practice and post-marketing drug surveillance. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2002;15:161–9.

Kampichit S, Pratipanawatr T, Jarernsiripornkul N. Confidence and accuracy in identification of adverse drug reactions reported by outpatients. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40(6):1559–67.

Chaipichit N, Krska J, Pratipanawatr T, Uchaipichat V, Jarernsiripornkul N. A qualitative study to explore how patients identify and assess symptoms as adverse drug reactions. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70(5):607–15.

Jarernsiripornkul N, Krska J, Capps PA, Richards RM, Lee A. Patient reporting of potential adverse drug reactions: a methodological study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;53(3):318–25.

Avery AJ, Anderson C, Bond CM, Fortnum H, Gifford A, Hannaford PC, et al. Evaluation of patient reporting of adverse drug reactions to the UK ‘Yellow Card Scheme’: literature review, descriptive and qualitative analyses, and questionnaire surveys. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15(20):1–234, iii–iv.

Walji R, Boon H, Barnes J, Austin Z, Welsh S, Baker GR. Consumers of natural health products: natural-born pharmacovigilantes? BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010;10:8.

Chiba T, Sato Y, Kobayashi E, Ide K, Yamada H, Umegaki K. Behaviors of consumers, physicians and pharmacists in response to adverse events associated with dietary supplement use. Nutr J. 2017;16(1):18.

Inman WH. Attitudes to adverse drug reaction reporting. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;41(5):434–5.

Yu YM, Lee E, Koo BS, Jeong KH, Choi KH, Kang LK, et al. Predictive factors of spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reactions among community pharmacists. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0155517.

Herdeiro MT, Figueiras A, Polonia J, Gestal-Otero JJ. Influence of pharmacists’ attitudes on adverse drug reaction reporting: a case-control study in Portugal. Drug Saf. 2006;29(4):331–40.

New Zealand Medicine and Medical Devices Safety Authority (MEDSAFE). Adverse reaction reporting in New Zealand—2018. Prescriber Update. 2019;40(1):10–1.

Jadeja M, McCreedy C. Positive effect of new medicine service on community yellow card reporting. Pharm J. 2012;289:159–60.

Harrison-Woolrych M, Coulter DM. PEM in New Zealand. In: Mann R, Andrews EB, editors. Pharmacovigilance. 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley; 2007. p. 317–32.

Bond C, Hannaford P. Issues related to monitoring the safety of over-the-counter (OTC) medicines. Drug Saf. 2003;26(15):1065–74.

Pharmacy Council of New Zealand. Code of Ethics 2018 Safe Effective Pharmacy Practice. Pharmacy Council of New Zealand. 2018. https://www.pharmacycouncil.org.nz/dnn_uploads/Documents/standardsguidelines/Code%20of%20Ethics%202018%20FINAL.pdf?ver=2018-03-04-215933-993. Accessed 16 Mar 2020.

van Eekeren R, Rolfes L, Koster AS, Magro L, Parthasarathi G, Al Ramimmy H, et al. What future healthcare professionals need to know about pharmacovigilance: introduction of the WHO PV core curriculum for university teaching with focus on clinical aspects. Drug Saf. 2018;41(11):1003–11.

Rutter P, Brown D, Howard J, Randall C. Pharmacists in pharmacovigilance: can increased diagnostic opportunity in community settings translate to better vigilance? Drug Saf. 2014;37(7):465–9.

World Health Organisation. WHO Global report on traditional and complementary medicine 2019. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2019. https://www.who.int/traditional-complementary-integrative-medicine/WhoGlobalReportOnTraditionalAndComplementaryMedicine2019.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 24 Apr 2020.

World Health Organisation. Pharmacovigilance and traditional and complementary medicine in South-East Asia: a situation review. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2019. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/325982/9789290227250-eng.pdf. Accessed 24 Apr 2020.

Savage RL, Hill GR, Barnes J, Kenyon SH, Tatley MV. Suspected hepatotoxicity with a supercritical carbon dioxide extract of Artemisia annua in grapeseed oil used in New Zealand. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1448.

Natural Health and Supplementary Products Bill. New Zealand Parliament. 2017. https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/bills-and-laws/bills-proposed-laws/document/00DBHOH_BILL11034_1/natural-health-and-supplementary-products-bill. Accessed 16 Mar 2020.

Zoio N. Natural health products bill quietly killed off. Pharmacy Today 2017;24 November:13. https://www.pharmacytoday.co.nz/article/print-archive/natural-health-products-bill-quietly-killed. Accessed 27 July 2020.

New Zealand Pharmacovigilance Centre: About-IMMP. New Zealand Pharmacovigilance Centre. https://nzphvc.otago.ac.nz/about/. Accessed 16 Mar 2020.

Acknowledgements

Lyn Lavery (Academic Consulting Ltd, New Zealand) was contracted to conduct the interviews and transcribing for this study, and data coding under the supervision of JB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was supported by a University of Auckland New Staff Grant (Grant number 3608425), and a New Zealand Pharmacy and Education Fund (NZ PERF) Grant (Grant number 173) to JB.

Conflict of Interest

JB has received fees, honoraria and travel expenses from the Pharmaceutical Society of New Zealand (PSNZ) for preparation and delivery of continuing education material on complementary medicines (CMs) for pharmacists (2013, 2015); provided consultancy to the Pharmacy Council of New Zealand on Code of Ethics statements on CMs (unpaid) and competence standards (paid); was a member of the New Zealand Ministry of Health Natural Health Products (NHPs) Regulations Subcommittee on the Permitted Substances List (2016–2017) for which she received fees and travel expenses; leads the Herbal and Traditional Medicines Special Interest Group of the International Society of Pharmacovigilance. JB is a registered pharmacist in NZ and has a personal viewpoint that supports regulation for CMs. JB has authored/co-authored reference textbooks for which she has received royalties in respect of sales from Pharmaceutical Press and Elsevier. RB has no conflicts of interest to declare. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare that influence, or could be perceived as influencing, this work.

Availability of Data and Material (Data Transparency)

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available as this is outside the terms of the ethics approval.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

JB was the principal investigator for this research: she designed the study and its tools, wrote the grant applications and obtained funding, wrote the ethics application, designed the coding frame, checked coding, analysed data, wrote the papers, and supervised and had overall responsibility for all aspects of the work. RB checked coding, undertook aspects of data analysis, and contributed to writing the papers. Both authors had complete access to the study data that support the publications.

Ethics Approval

Ethical approval was given by the University of Auckland Human Participants Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 5008) on 12 September 2007.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to Publish

All authors consent to publication of this paper.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barnes, J., Butler, R. Community Pharmacists’ Views and Experiences with ADR Reporting for Complementary Medicines: A Qualitative Study in New Zealand. Drug Saf 43, 1157–1170 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-020-00980-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-020-00980-x