Abstract

Purpose of Review

In addition to concerns with physical health and activity levels, children with cardiac conditions can be at risk of neurodevelopmental and socioemotional maladjustment. Children with congenital heart defects requiring surgery early in life are at risk of developmental delays and cognitive impairments, and both children with congenital heart defects and those with cardiomyopathies are at risk of socioemotional concerns. As a result, there is an increasing focus on rehabilitation efforts for these patients, in order to improve both their physical well-being and their adjustment outcomes. However, there are no established standards for rehabilitation programs applicable across children with cardiac conditions, in stark contrast to guidelines for adult patients. The purpose of the present review is to summarize recent studies on pediatric cardiac rehabilitation and describe the structure of our own program, in order to aid with the delineation of future guidelines.

Recent Findings

Twenty programs for pediatric cardiac rehabilitation were identified and reviewed. We review inpatient, outpatient, and home-based programs, most of which include two to three sessions of exercise training per week for 12 weeks with a focus on improving exercise capacity. We also review emerging cognitive rehabilitation for children with cardiac disorders and discuss a newly developed program at our own institution.

Summary

A review of past findings, along with recent efforts at our institution, suggests that a structured cardiac rehabilitation program can benefit children by increasing exercise response and physical activity as well as improving developmental, cognitive, and psychosocial outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Children with cardiac disorders are at risk of neurodevelopmental and socioemotional maladjustment [1,2,3,4], on top of concerns with their physical health and activity levels. As a result, there is an increasing focus on rehabilitation efforts for these patients, in order to improve both their physical well-being and their psychosocial adjustment. However, there are no established standards for rehabilitation programs applicable across children with cardiac conditions, in stark contrast to guidelines for adults [5]. In this review, we summarize recent studies on pediatric cardiac rehabilitation and present the structure of our own center’s program, in order to aid with the delineation of future guidelines for pediatric patients.

Pediatric Cardiac Disorders

Congenital Heart Defects

Congenital heart defects (CHDs) are one of the most common birth defects, affecting approximately 1.35 million newborns worldwide every year [6] and 1 million children of all ages in the USA [7]. CHDs encompass a wide range of conditions in which there is abnormal development of the heart and/or its major blood vessels; they are broadly categorized into cyanotic defects (where oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood mix) and acyanotic defects (where the amount of oxygen delivered throughout the body is unaffected). A summary of heart defects is provided in Table 1, with abbreviated details on clinical presentation and management.

Children with CHDs can have comorbid pulmonary and other medical complications hindering their ability to function [8, 9], and they are at risk of delays in motor development and exercise intolerance [10, 11]. Impairments in motor functioning and exercise tolerance, in turn, have been linked with perioperative morbidity and sedentary behaviors (which can have negative health consequences) [12]. Along with their physical impairments, children with CHDs are more likely to have parents, educators, and health providers who excessively limit their activity, predisposing them to physical inactivity and exercise intolerance [13]. They may, therefore, benefit from cardiac rehabilitation with an emphasis on increasing physical activity and providing relevant education.

Children with CHDs are also at increased risk of early developmental delays, later cognitive dysfunction, and poor quality of life, including speech and language delays, deficits in attention, executive functioning and visuospatial skills, and emotional and behavioral dysregulation [1, 2]. Neurodevelopmental disruptions are thought to result from a combination of brain dysmaturation [14,15,16] (which likely arises from genetic factors and teratogens that concurrently impact cardiac and cerebral fetal development [17, 18]), altered cerebral perfusion (which can then affect functional and structural brain development) [19], and neurological injuries (i.e., cerebral hemorrhages, ischemic lesions, periventricular leukomalacia, and other white matter injuries) [20, 21]. The complexity of the heart defect has been related to the severity of neurodevelopmental concerns, with children with single ventricle lesions thought to be at particular risk [1]. Even with simpler defects, though, factors such as cardiac arrest [22] and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) [23] can portend increased risk of neurodevelopmental delay. As such, children with CHDs may benefit from access to habilitation and rehabilitation services, during acute care following surgical interventions, cardiac arrest, and ECMO but also follow-up interventions for functional impairments or developmental delays that emerge throughout childhood.

Cardiomyopathies

Cardiomyopathies occur in fewer than 2 per 100,000 children [24, 25]. Cardiomyopathies are abnormalities of the ventricular myocardium that cannot be explained by abnormal loading conditions or heart defects; they can result from coronary artery abnormalities, tachyarrhythmias, exposure to infection or toxins, or other underlying disorders [26]. There are several subtypes of cardiomyopathies, summarized in Table 2 along with their presentation and management.

In many children with cardiomyopathies, the disorder progresses to the point where medications and surgical options are ineffective. Nearly 40% of children with symptomatic cardiomyopathy require a heart transplant or die [27, 28]. The time to transplant or death for children with cardiomyopathy has notably not improved over the past several decades, and the most economically advanced nations have no better survival outcomes than developing nations [29]. Rehabilitation programs may be beneficial, not to cure the diseases, but to potentially improve the cardiac function and the overall health of children for whom options for care are limited [30••].

Children with cardiomyopathies, particularly those who progress to heart failure, have an increased risk of anxiety, depression, and quality of life concerns [3, 31••]. In addition, those who require permanent ventricular assist devices or heart transplantation can have mild neurodevelopmental disruptions [4, 32]. Among adults, cardiac rehabilitation programs have yielded success in improving not only cardiac function and overall physical activity but also emotional well-being and quality of life. Children may similarly benefit from rehabilitation programs.

Heart Transplantation

Per the Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation [33], there are approximately 400 to 600 cases of pediatric heart transplantation per year, worldwide. CHDs are the most common indication for transplant during infancy (55% of cases), followed by cardiomyopathies (37%). However, for children over age 10, cardiomyopathies are the most common indication (43–54% dependent on age). The median post-transplant survival is approximately 22 years for those transplanted in infancy, approximately 18 years for those in early childhood (age 1–5 years), approximately 14 years for those in middle childhood (age 6–10 years), and 13 years for those in adolescence.

Cardiac transplantation results in postganglionic denervation, leading to the inability to respond to the parasympathetic nervous system [34]. In turn, there are higher systolic and diastolic blood pressures, elevated heart rate at rest, lower maximal myocardial oxygen consumption, lower heart rate reserve, and decreased exercise duration. Because of these physiologic changes, cardiac rehabilitation can be helpful in reestablishing physical health and activity levels.

Heart transplantation in infancy and toddlerhood has been associated with mild delays in motor and cognitive development, with a similar pattern of deficits as seen with children with CHDs requiring surgery other than transplantation early in life [35]. Specifically, this group can display mild reductions in motor skills, intellectual abilities, language abilities, and visuospatial skills. Older children, who often undergo a heart transplant for cardiomyopathy, can display mild cognitive deficits and are, more importantly, at risk of internalizing and externalizing distress [36]. Among children who undergo heart transplantation, cardiac rehabilitation may be particularly important not only to help pediatric patients regain their strength and mobility in the short term but also to help maximize children’s quality of life across their reduced lifespan.

Pediatric Cardiac Rehabilitation

Guidelines from the American Heart Association and the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation recommended that cardiac rehabilitation programs for adults and older adults include several core components including a baseline assessment, management of health risk factors (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, lipid levels) and nutrition, exercise training and physical activity counseling, and psychosocial management [37,38,39]. Similarly, primary goals for pediatric cardiac rehabilitation are managing physical health and activity as well as socioemotional functioning. Given the key developmental tasks of childhood, such as gaining basic academic skills, there may be an additional focus on mitigating developmental and cognitive disruptions, which would not be a primary concern during adult cardiac rehabilitation.

Addressing Physical Health and Activity

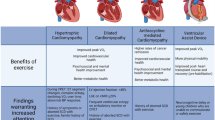

Historically, there have been concerns regarding the adverse effects of physical activity in those with cardiac conditions. However, research has underscored that exercise is not necessarily contraindicated. For example, a large study among adults with CHDs demonstrated that the majority of sudden cardiac events in patients occurred at rest (69%), with 11% during sleep, and only 10% during exercise [40]. In fact, physical activity can be beneficial for those with cardiac conditions. There is overwhelming evidence that exercise training within adult cardiac rehabilitation promotes cardiorespiratory fitness, strength, flexibility, and metabolic health; reduces morbidity, mortality, and hospital admissions; and improves quality of life [41•, 42•]. Emerging research with pediatric populations with cardiac conditions similarly suggests that exercise training can have beneficial effects, although there is some variability in effects [43, 44].

Given its potential benefit, exercise training has been outlined as a key component of cardiac rehabilitation with adult patients [37,38,39], recommended in guidelines for certain pediatric cardiac populations (e.g., those with heart failure), and has consistently been included in emerging programs with children [30••, 43,44,45]. From prior reviews of cardiac rehabilitation programs for children with CHDs or cardiomyopathies [30••, 43, 44], it has generally been recommended that programs have a duration of at least 12 weeks, with two to three sessions per week, and sessions of at least 30 min (and up to 90 min). Programs should include aerobic, resistance, and flexibility training, with warm-up and cool-down periods. Training should be individualized based on the results of metabolic stress tests, cardiac biomarkers, echocardiograms, baseline resistance-training capacity, and past medical history. Notably, the intensity of aerobic exercise should be at a heart rate approximately equivalent to anaerobic threshold. The patient’s progress should be reviewed at least weekly, and progressive increases should be made in the child’s exercise workload as tolerated and when medically appropriate. Programs might also benefit from a 6-month maintenance period with two exercise visits per month, including a review of exercise logs. Both center-based and at-home training programs may be effective [30••].

More broadly, cardiac rehabilitation programs can provide education on appropriate physical activity in children with cardiac conditions. Physical activity has been promoted in guidelines from the American Heart Association and the Association for European Paediatric Cardiology for children with CHDs [46••, 47]. Specifically, guidelines for physical activity in children with CHDs underscore the need for at least 60 min of daily activity that is developmentally appropriate and enjoyable. Vigorous activity is recommended at least 3 days per week, and exercises for strengthening bone and muscle (e.g., high-impact and anaerobic burst exercises such as jumping) are recommended 3 days per week. However, children with certain heart defects (e.g., transposition of the great arteries, single ventricle conditions) may need to limit participation in the highest intensity activities, notably in competitive sports [48]. As for all children, screen time should be limited to no more than 2 h per day for children over the age of 5 years, and children under the age of 3 years should not have any screen time [46••, 47].

Guidelines from the American Heart Association and the European Society of Cardiology for individuals with cardiomyopathies also underscore the benefit of physical activity [49, 50, 51••]. Still, those with cardiomyopathies may have more restrictions in their activity. Intensive exercise programs and competitive sport may be contraindicated for certain individuals depending on their subtype of cardiomyopathy, history of symptoms, and findings on cardiac testing. More generally, patients should be advised to start exercise sessions with a warm-up period and end with a cool-down period; avoid burst exertion, preferably avoid high-intensity free weight lifting due to the risk of injury with syncope; avoid exercising in adverse environmental conditions; and exercise only in environments equipped with an automatic defibrillator.

In addition to exercise training and counseling on appropriate physical activity, pediatric cardiac rehabilitation programs can help patients and their families establish a nutrition plan and better recognize and manage the symptoms of their cardiac condition. As such, programs can promote a healthy lifestyle and decrease the risk and the severity of future cardiovascular disease.

Addressing Cognitive and Socioemotional Functioning

Cardiac rehabilitation programs can help not only mitigate the physiological effects of cardiac conditions but also enhance the socioemotional and cognitive functioning of patients. By doing so, cardiac rehabilitation programs can help children, adolescents, and young adults transition back to their family and home life, peer groups, and school and work settings following hospitalization. Although such efforts are standard in programs with adult patients, recent reviews suggested that the same cannot be said of pediatric programs, even though the omission of mental health providers may decrease the success of cardiac rehabilitation [43, 44].

Psychologists, social workers, and other licensed mental health professionals can assess the psychosocial needs of pediatric patients and their families and monitor changes in needs throughout their rehabilitation [52]. For example, although patients have typically undergone a psychosocial evaluation prior to a heart transplant, their needs may change during the waiting period for a heart and subsequent recovery from surgery. Families may also be more likely to report sensitive information once they no longer need to be concerned that they may not be listed for a transplant because of their financial, social, or personal resources. They may also share important information once they feel more comfortable with their care team over time. As such, they may be more apt to discuss difficulty coping with their illness and medical care, negative mood, insufficient social support, and/or premorbid history of mental health concerns.

Having identified patients’ needs, mental health providers can implement interventions to foster healthy behaviors and treatment compliance and address the distress associated with critical illness and lengthy hospital stays. For instance, motivational interviewing strategies can aid with building a desire to engage in adaptive behaviors, such as taking medications and following nutrition and exercise plans [53, 54]. Strategies from behavioral management therapy can target the behavioral manifestations of distress often seen in young children, and cognitive-behavioral and mindfulness-based therapies can effectively target anxious, irritable, and depressed moods among older children and adolescent [55,56,57]. Behavioral and cognitive-behavioral therapies also offer models for chronic pain and poor sleep [58, 59]. The ability to consult psychiatric colleagues within cardiac rehabilitation programs further allows pediatric patients access to specialized psychotropic medication management when indicated.

Interestingly, psychological interventions might benefit physical health along with psychosocial health. In a meta-analysis of 23 randomized control trials involving adult patients with coronary heart disease, psychological interventions both reduced emotional distress and improved systolic blood pressure, heart rate, and cholesterol levels [60]. Similarly, a pediatric cardiac rehabilitation program with a stress management component improved physiological measurements, although the study did not separate out the effects of exercise training, health education, and stress management [61]. Research has also documented associations between physical and emotional health among youths who have completed cardiac rehabilitation [62•] and between daily physical activity and mental health among children with CHDs [63].

Cardiac rehabilitation programs can furthermore offer an opportunity to identify and address disruptions in the acquisition of developmental milestones and cognitive abilities. Developmental assessments can identify delays in motor, language, and adaptive development, and neuropsychological evaluations can identify cognitive deficits [1]. Such testing can aid with treatment and transition planning (e.g., clarifying the need for speech and language therapy and outlining recommendations for an Individualized Education Program upon return to school).

Importantly, families of children with cardiac disorders have described the need for effective communication among health and mental health professionals, families, and schools as critical within rehabilitation programs [64]. By incorporating mental health providers, care coordinators, and school liaisons into comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation programs, the needs of pediatric patients can be better understood and addressed by the treatment team.

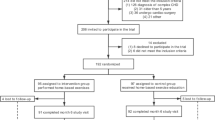

Rehabilitation Programs

As summarized in Table 3, we identified 20 cardiac rehabilitation programs described across 26 reports, with samples that included patients under age 18. Due to the limited number of studies and consistency in findings, we did not exclude programs that had both pediatric and adult patients. Similarly, we included both randomized control trials and investigations without control groups, due to the emerging nature of the literature. Programs described within case studies and unpublished manuscripts (e.g., theses, conference presentations) were excluded from the review. We only included reports written in English and papers published after 1990.

Below, we describe pediatric cardiac rehabilitation programs designed for inpatient and outpatient settings as well as home-based training. Across the different settings, programs typically adopted a team approach with physicians, rehabilitation therapists, and other health providers. Indeed, it has previously been recommended that programs include dieticians, physical therapists, and occupational therapists at minimum and be coordinated by a pediatric cardiologist and a pediatric physiatrist [30••]. Staff should be trained to handle medical emergencies, and the staff-to-patient ratio should not exceed 1 to 4 at any time, per prior recommendations [30••].

Inpatient Acute Care Rehabilitation

The literature is limited in regard to programs that include rehabilitation during the acute care hospitalization period. Still, we identified two reports describing inpatient acute care rehabilitation, one featuring patients with a ventricular assist device and one focused on patients hospitalized for heart failure [65, 66]. The programs demonstrated the safety and feasibility of an acute care model both in the intensive care setting and on a standard hospital floor, with no adverse events related to physical activity. One of the rehabilitation programs additionally documented that patients were able to achieve the therapeutic goals established for them [65].

Outpatient Rehabilitation

We identified nine outpatient programs, described across 14 studies [61, 62•, 67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77, 78•]. The programs included patients as young as 8 years old; although three of the programs included young adults and one included patients as old as 40 years, they all enrolled children and/or adolescents. All of the studies evaluated effects of exercise in patients with CHDs. The duration of the programs ranged from 2 weeks to 8 months, with structured activity typically two to three times per week, typically for 30 min to 60 min per session. The programs all included some form of warm-up and cool-down periods (typically 5 min to 10 min each). All of the programs included an aerobic component to the exercise training program, and some also included strength training. All of the programs demonstrated an improvement in maximal oxygen output. Studies also reported exercise duration, metabolic equivalents, and improved quality of life. One of the programs also documented self-reported improvements in cognitive functioning and parent-reported improvements in social functioning [69,70,71,72].

Home-Based Rehabilitation

Nine programs, summarized across ten reports, described home-based rehabilitation programs [79•, 80, 81•, 82,83,84,85,86,87,88]. Although the majority of studies focused on school-age and adolescent patients with CHDs, there was one program that focused on toddlers [87], one that included young adults [85], and one that enrolled patients following heart transplantation [88]. Programs often required 8 weeks to 12 weeks of home-based exercise and included initial and follow-up sessions in person with health providers, so as to provide education on the program and monitor progress. Progress could also be monitored with digital tools, such as heart rate monitors, accelerometers, and Fitbits. Echoing the design of outpatient programs, home-based rehabilitation programs typically involved sessions of an hour or less with 5-min to 10-min warm-up and cool-down periods and focus on aerobic exercise. Although training was often associated with improved exercise capacity, better cardiorespiratory outcomes, and improved quality of life and psychosocial functioning, one study did not find significant changes in patients after the intervention [79•]. Interestingly, the program with toddlers reported improvements in gross motor functioning, daily physical activity, and family life up to 2 years later [87], and a program with school-age children documented improvements in exercise capacity and quality of life up to a year after the intervention [80]. None of the programs reported significant adverse events.

Cognitive Rehabilitation

The vast majority of rehabilitation programs among children with cardiac conditions have focused on exercise training, as a function of children’s complex medical needs. However, we mention one study underway to examine cognitive rehabilitation among children with cardiac conditions. Newburger [89] is investigating the effects of a computer-based training program to enhance the executive functioning skills of children with CHDs.

Current Directions at Our Institution

At the UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh (CHP), we developed a cardiac rehabilitation program modeled after recommendations from previously developed programs, as described above. The program seeks to establish a reproducible and sustainable protocol for children with pediatric-onset or congenital cardiac disease, in an effort to systematically influence and mitigate the effects on physical health, neurodevelopmental outcomes, and quality of life. Specifically, the goals of the program are to (1) improve exercise function and capacity; (2) improve heart rate recovery and response to exercise; (3) decrease the effects of deconditioning; (4) improve physical function and age appropriate level of play and adaptive living; (5) improve patient and family confidence in exercise and participation in age appropriate activities; (6) promote global wellness, including an active lifestyle and healthy nutrition choices; and (7) improve overall adjustment and quality of life post transplantation.

With this framework in mind, we established multidisciplinary inpatient and outpatient cardiac rehabilitations programs, which involve medical evaluation, prescribed therapies, nutritional and physical education geared toward improving the physiologic effects of long-term cardiac illness, and consultation for developmental, neuropsychological, and psychological services. The team, headed by a pediatric cardiologist and pediatric physiatrist, also includes physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech and language pathologists, dieticians, neuropsychologists, and pediatric psychologists. This team meets at a regularly scheduled time to review patients for clinic care and to advance the cardiac rehabilitation program’s development.

Currently, our institution is targeting children on the pathway to heart transplantation for participation in pediatric cardiac rehabilitation; however, we hope to expand our program more broadly to children with CHDs and cardiomyopathies not requiring heart transplantation. The program structure includes providing a multidisciplinary evaluation prior to transplantation, including assessments from medical and therapy providers. Based on the evaluation, the team provides a cohesive set of recommendations, including a potential course of therapies prior to transplantation. Following cardiac transplantation, patients are typically engaged in a 12-week outpatient course of physical therapy three times per week (with sessions lasting between 30 and 60 min), with aerobic conditioning, resistance, and strength training. Sessions include warm-up and cool-down periods. As needed, patients are engaged in occupational therapy with a focus on adaptive skills following surgery, speech and language therapy with a focus on cognitive restructuring, and nutrition and physical activity education. These sessions can occur at facilities associated with the hospital for families that live close by; otherwise, a prescription detailing needed interventions is provided to the family to take to a facility in their community. As needed, patients are engaged in psychotherapy to aid with their psychosocial adjustment. Patients may also be referred for neuropsychological testing to determine their cognitive needs, as they return to the school and home environment; evaluations are conducted following guidelines for assessment in children with cardiac disorders [90••].

Conclusion

Children can benefit from pediatric cardiac rehabilitation programs from physical health and psychosocial perspectives, and more importantly, these programs can be tolerated with minimal adverse events. Although center-based programs may allow for a greater degree of refinement in individual patient goals and monitoring of their health status, the limitation of proximity to a tertiary care institution is not necessarily a barrier (particularly among children with chronic concerns, such as CHDs), as demonstrated by the efficacy of home-based programs. The home-based program has the potential to limit the burden of transportation and potentially time off work for parents who bring their child to a facility for training. Still, home-based programs should continue to be monitored by both a cardiologist and a pediatric physiatrist. Further research is needed to demonstrate sustained long-term benefits of interventions, to understand the impact on quality of life for the family system, and to explore long-term impact of cognitive interventions within pediatric cardiac rehabilitation programs.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Marino BS, Lipkin PH, Newburger JW, Peacock G, Gerdes M, Gaynor JW, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with congenital heart disease: evaluation and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;126(9):1143–72.

Bellinger DC, Newburger JW. Neuropsychological, psychosocial, and quality-of-life outcomes in children and adolescents with congenital heart disease. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2010;29(2):87–92.

Friess MR, Marino BS, Cassedy A, Wilmot I, Jefferies JL, Lorts A. Health-related quality of life assessment in children followed in a cardiomyopathy clinic. Pediatr Cardiol. 2015;36(3):516–23.

Brosig C, Hintermeyer M, Zlotocha J, Behrens D, Mao J. An exploratory study of the cognitive, academic, and behavioral functioning of pediatric cardiothoracic transplant recipients. Prog Transplant. 2006;16(1):38–45.

Dalal HM, Doherty P, Taylor RS. Cardiac rehabilitation. BMJ. 2015;351:h5000.

van der Linde D, Konings EE, Slager MA, Witsenburg M, Helbing WA, Takkenberg JJ, et al. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(21):2241–7.

Gilboa SM, Devine OJ, Kucik JE, Oster ME, Riehle-Colarusso T, Nembhard WN, et al. Congenital heart defects in the United States: estimating the magnitude of the affected population in 2010. Circulation. 2016;134(2):101–9.

Cooper DS, Jacobs JP, Chai PJ, Jaggers J, Barach P, Beekman RH, et al. Pulmonary complications associated with the treatment of patients with congenital cardiac disease: consensus definitions from the Multi-Societal Database Committee for Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease. Cardiol Young. 2008;18(S2):215–21.

Limperopoulos C, Majnemer A, Shevell MI, Rosenblatt B, Rohlicek C, Tchervenkov C, et al. Functional limitations in young children with congenital heart defects after cardiac surgery. Pediatrics. 2001;108(6):1325–31.

Holm I, Fredriksen PM, Fosdahl MA, Olstad M, Vollestad N. Impaired motor competence in school-aged children with complex congenital heart disease. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(10):945–50.

Hovels-Gurich HH, Konrad K, Skorzenski D, Nacken C, Minkenberg R, Messmer BJ, et al. Long-term neurodevelopmental outcome and exercise capacity after corrective surgery for tetralogy of Fallot or ventricular septal defect in infancy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(3):958–66.

Giardini A, Specchia S, Tacy TA, Coutsoumbas G, Gargiulo G, Donti A, et al. Usefulness of cardiopulmonary exercise to predict long-term prognosis in adults with repaired tetralogy of Fallot. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99(10):1462–7.

Casey FA, Stewart M, McCusker CG, Morrison ML, Molloy B, Doherty N, et al. Examination of the physical and psychosocial determinants of health behaviour in 4–5-year-old children with congenital cardiac disease. Cardiol Young. 2010;20(5):532–7.

Limperopoulos C, Tworetzky W, McElhinney DB, Newburger JW, Brown DW, Robertson RL Jr, et al. Brain volume and metabolism in fetuses with congenital heart disease evaluation with quantitative magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. Circulation. 2010;121(1):26–33.

Licht DJ, Shera DM, Clancy RR, Wernovsky G, Montenegro LM, Nicolson SC, et al. Brain maturation is delayed in infants with complex congenital heart defects. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137(3):529–37.

von Rhein M, Buchmann A, Hagmann C, Huber R, Klaver P, Knirsch W, et al. Brain volumes predict neurodevelopment in adolescents after surgery for congenital heart disease. Brain. 2013;137(1):268–76.

Bruneau BG. The developmental genetics of congenital heart disease. Nature. 2008;451(7181):943–8.

Clifford A, Lang L, Chen R. Effects of maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy on cognitive parameters of children and young adults: a literature review. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2012;34(6):560–70.

Claessens NH, Kelly CJ, Counsell SJ, Benders MJ. Neuroimaging, cardiovascular physiology, and functional outcomes in infants with congenital heart disease. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59(9):894–902.

Owen M, Shevell M, Majnemer A, Limperopoulos C. Abnormal brain structure and function in newborns with complex congenital heart defects before open heart surgery: a review of the evidence. J Child Neurol. 2011;26(6):743–55.

von Rhein M, Scheer I, Loenneker T, Huber R, Knirsch W, Latal B. Structural brain lesions in adolescents with congenital heart disease. J Pediatr. 2011;158(6):984–9.

van Zellem L, Buysse C, Madderom M, Legerstee JS, Aarsen F, Tibboel D, et al. Long-term neuropsychological outcomes in children and adolescents after cardiac arrest. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(6):1057–66.

Brown KL, Ichord R, Marino BS, Thiagarajan RR. Outcomes following extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in children with cardiac disease. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14(5_suppl):S73–83.

Lipshultz SE, Sleeper LA, Towbin JA, Lowe AM, Orav EJ, Cox GF, et al. The incidence of pediatric cardiomyopathy in two regions of the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1647–55.

Nugent AW, Daubeney PE, Chondros P, Carlin JB, Cheung M, Wilkinson LC, et al. National Australian Childhood Cardiomyopathy Study. The epidemiology of childhood cardiomyopathy in Australia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1639–46.

Lee TM, Hsu DT, Kantor P, Towbin JA, Ware SM, Colan SD, et al. Pediatric cardiomyopathies. Circ Res. 2017;121(7):855–73.

Bilgiç A, Özbarlas N, Özkutlu S, Özer S, Özme S. Cardiomyopathies in children: clinical, epidemiological and prognostic evaluation. Jpn Heart J. 1990;31(6):789–97.

Lipshultz SE. Ventricular dysfunction clinical research in infants, children and adolescents. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2000;12:1–28.

Boucek MM, Edwards LB, Keck BM, Trulock EP, Taylor DO, Mohacsi PJ, et al. The registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: sixth official pediatric report—2003. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22(6):636–52.

•• Somarriba G, Extein J, Miller TL. Exercise rehabilitation in pediatric cardiomyopathy. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;25(1):91–102. This article nicely outlines the benefits of each component of pediatric cardiac rehabilitation in addition to laying out an outline for a program format.

Hollander SA, Callus E. Cognitive and psycholologic considerations in pediatric heart failure. J Card Fail. 2014;20(10):782–5.

Stein ML, Bruno JL, Konopacki KL, Kesler S, Reinhartz O, Rosenthal D. Cognitive outcomes in pediatric heart transplant recipients bridged to transplantation with ventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32(2):212–20.

Rossano JW, Cherikh WS, Chambers DC, Goldfarb S, Khush K, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: twentieth pediatric heart transplantation report-2017. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017;36(10):1060–9.

Wilson RF, Johnson TH, Haidet GC, Kubo SH, Mianuelli M. Sympathetic reinnervation of the sinus node and exercise hemodynamics after cardiac transplantation. Circulation. 2000;101:2727–273.

Antonini TN, Dreyer WJ, Caudle SE. Neurodevelopmental functioning in children being evaluated for heart transplant prior to 2 years of age. Child Neuropsychology. 2018;24(1):46–60.

Todaro JF, Fennell EB, Sears SF, Rodrigue JR, Roche AK. Cognitive and psychological outcomes in pediatric heart transplantation. J Pediatr Psychol. 2000;25(8):567–76.

Balady GJ, Ades PA, Comoss P, Limacher M, Pina IL, Southard D, et al. Core components of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association and the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation Writing Group. Circulation. 2000;102:1069–73.

Balady GJ, Williams MA, Ades PA, Bittner V, Comoss P, Foody JM, et al. Core components of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs: 2007 update: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention Committee, the Council on Clinical Cardiology, the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Epidemiology and Prevention, and Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism, and the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Circulation. 2007;115(20):2675–82.

Williams MA, Fleg JL, Ades PA, Chaitman BR, Miller NH, Mohiuddin SM, et al. Secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in the elderly (with emphasis on patients ≥ 75 years of age) an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology Subcommittee on Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention. Circulation. 2002;105(14):1735–43.

Koyak Z, Harris L, de Groot JR, Silversides CK, Oechslin EN, Bouma BJ, et al. Sudden cardiac death in adult congenital heart disease. Circulation. 2012;126(16):1944–54.

• Anderson L, Oldridge N, Thompson DR, Zwisler AD, Rees K, Martin N, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(1):1–12. In this systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiac rehabilitation programs with adults with coronary heart disease, 63 studies with 14,486 participants are reviewed. The authors conclude that exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation reduces cardiovascular mortality and hospital admissions and improves quality of life.

• Dias KA, Link MS, Levine BD. Exercise training for patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(10):1157–65. This review discusses the evidence supporting the safety and efficacy of different intensities of exercise training in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and considers novel strategies to improve fitness in adults.

Tikkanen AU, Oyaga AR, Riano OA, Alvaro EM, Rhodes J. Paediatric cardiac rehabilitation in congenital heart disease: a systematic review. Cardiol Young. 2012;22(3):241–50.

Duppen N, Takken T, Hopman MT, ten Harkel AD, Dulfer K, Utens EM, et al. Systematic review of the effects of physical exercise training programmes in children and young adults with congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(3):1779–87.

Kirk R, Dipchand AI, Rosenthal DN, Addonizio L, Burch M, Chrisant M, et al. The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation guidelines for the management of pediatric heart failure: executive summary. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(9):888–909.

•• Longmuir PE, Brothers JA, de Ferranti SD, Hayman LL, Van Hare GF, Matherne GP, et al. Promotion of physical activity for children and adults with congenital heart disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127(21):2147–59. This paper describes physical activity recommendations in individuals with congenital heart disease and is an important statement coming from the American Heart Association. The article also makes suggestions for potential research protocols to further knowledge in this realm.

Takken T, Giardini A, Reybrouck T, Gewillig M, Hövels-Gürich HH, Longmuir PE, et al. Recommendations for physical activity, recreation sport, and exercise training in paediatric patients with congenital heart disease: a report from the Exercise, Basic & Translational Research Section of the European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation, the European Congenital Heart and Lung Exercise Group, and the Association for European Paediatric Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;19(5):1034–65.

Graham TP, Driscoll DJ, Gersony WM, Newburger JW, Rocchini A, Towbin JA. Task force 2: congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(8):1326–33.

Maron BJ, Chaitman BR, Ackerman MJ, Bayes de Luna A, Corrado D, Crosson JE, et al. Recommendations for physical activity and recreational sports participation for young patients with genetic cardiovascular diseases. Circulation. 2004;109(22):2807–16.

January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Conti JB, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(21):2246–80.

•• Pelliccia A, Solberg EE, Papadakis M, Adami PE, Biffi A, Caselli S, et al. Recommendations for participation in competitive and leisure time sport in athletes with cardiomyopathies, myocarditis, and pericarditis: position statement of the Sport Cardiology Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). Eur Heart J. 2018;40(1):19–33. This position paper offers a comprehensive overview of the most updated recommendations for practicing cardiologists and sport physicians managing athletes with cardiomyopathies and myopericarditis and provides pragmatic advice for safe participation in competitive sport at professional and amateur levels, as well as in a variety of recreational physical activities.

Annunziato RA, Fisher MK, Jerson B, Bochkanova A, Shaw RJ. Psychosocial assessment prior to pediatric transplantation: a review and summary of key considerations. Pediatr Transplant. 2010;14(5):565–74.

Suarez M, Mullins S. Motivational interviewing and pediatric health behavior interventions. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29(5):417–28.

Gayes LA, Steele RG. A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing interventions for pediatric health behavior change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82(3):521–35.

Thomas R, Abell B, Webb HJ, Avdagic E, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. Parent-child interaction therapy: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20170352.

Compton SN, March JS, Brent D, Albano AM, Weersing VR, Curry J. Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for anxiety and depressive disorders in children and adolescents: an evidence-based medicine review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(8):930–59.

Klingbeil DA, Renshaw TL, Willenbrink JB, Copek RA, Chan KT, Haddock A, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions with youth: a comprehensive meta-analysis of group-design studies. J Sch Psychol. 2017;63:77–103.

Meltzer LJ, Mindell JA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions for pediatric insomnia. J Pediatr Psychol. 2014;39(8):932–48.

Palermo TM, Eccleston C, Lewandowski AS, Williams AC, Morley S. Randomized controlled trials of psychological therapies for management of chronic pain in children and adolescents: an updated meta-analytic review. PAIN. 2010;148(3):387–97.

Linden W, Stossel C, Maurice J. Psychosocial interventions for patients with coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(7):745–52.

Balfour IC, Drimmer AM, Nouri S, Pennington DG, Hemkens CL, Harvey LL. Pediatric cardiac rehabilitation. Am J Dis Child. 1991;145(6):627–30.

• Rhodes J, Curran TJ, Camil L, Rabideau N, Fulton DR, Gauthier NS, et al. Sustained effects of cardiac rehabilitation in children with serious congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):e586–93. This study is one of few that demonstrated sustained long-term effects of pediatric cardiac rehabilitation.

Müller J, Christov F, Schreiber C, Hess J, Hager A. Exercise capacity, quality of life, and daily activity in the long-term follow-up of patients with univentricular heart and total cavopulmonary connection. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(23):2915–20.

Kendall L, Sloper P, Lewin RJ, Parsons JM. The views of parents concerning the planning of services for rehabilitation of families of children with congenital cardiac disease. Cardiol Young. 2003;13(1):20–7.

Hollander SA, Hollander AJ, Rizzuto S, Reinhartz O, Maeda K, Rosenthal DN. An inpatient rehabilitation program utilizing standardized care pathways after paracorporeal ventricular assist device placement in children. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(6):587–92.

McBride MG, Binder TJ, Paridon SM. Safety and feasibility of inpatient exercise training in pediatric heart failure: a preliminary report. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2007;27(4):219–22.

Brassard P, Poirier P, Martin J, Noël M, Nadreau E, Houde C, et al. Impact of exercise training on muscle function and ergoreflex in Fontan patients: a pilot study. Int J Cardiol. 2006;107(1):85–94.

Dedieu N, Fernández L, Garrido-Lestache E, Sánchez I, Lamas MJ. Effects of a cardiac rehabilitation program in patients with congenital heart disease. Open J Inter Med. 2014;4(01):22–7.

Dulfer K, Duppen N, Kuipers IM, Schokking M, van Domburg RT, Verhulst FC, et al. Aerobic exercise influences quality of life of children and youngsters with congenital heart disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(1):65–72.

Dulfer K, Duppen N, Blom NA, van Dijk AP, Helbing WA, Verhulst FC, et al. Effect of exercise training on sports enjoyment and leisure-time spending in adolescents with complex congenital heart disease: the moderating effect of health behavior and disease knowledge. Congenit Heart Dis. 2014;9(5):415–23.

Duppen N, Etnel JR, Spaans L, Takken T, van den Berg-Emons RJ, Boersma E, et al. Does exercise training improve cardiopulmonary fitness and daily physical activity in children and young adults with corrected tetralogy of Fallot or Fontan circulation? A randomized controlled trial. Am Heart J. 2015;170(3):606–14.

Duppen N, Kapusta L, de Rijke YB, Snoeren M, Kuipers IM, Koopman LP, et al. The effect of exercise training on cardiac remodelling in children and young adults with corrected tetralogy of Fallot or Fontan circulation: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Cardiol. 2015;179:97–104.

Fredriksen PM, Kahrs N, Blaasvaer S, Sigurdsen E, Gundersen O, Roeksund O, et al. Effect of physical training in children and adolescents with congenital heart disease. Cardiol Young. 2000;10(2):107–14.

Opocher F, Varnier M, Sanders SP, Tosoni A, Zaccaria M, Stellin G, et al. Effects of aerobic exercise training in children after the Fontan operation. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95(1):150–2.

Rhodes J, Curran TJ, Camil L, Rabideau N, Fulton DR, Gauthier NS, et al. Impact of cardiac rehabilitation on the exercise function of children with serious congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1339–45.

Singh TP, Curran TJ, Rhodes J. Cardiac rehabilitation improves heart rate recovery following peak exercise in children with repaired congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2007;28(4):276–9.

Sklansky MS, Pivarnik JM, Smith EO, Morris J, Bricker JT. Exercise training hemodynamics and the prevalence of arrhythmias in children following tetralogy of Fallot repair. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 1994;6(2):188–200.

• Wittekind S, Mays W, Gerdes Y, Knecht S, Hambrook J, Border W, et al. A novel mechanism for improved exercise performance in pediatric Fontan patients after cardiac rehabilitation. Pediatr Cardiol. 2018;39(5):1023–30. In this prospective study, pediatric patients with a history of the Fontan procedure completed a cardiac rehabilitation program for 12 weeks. There were significant improvements in both submaximal and peak exercise performance, with no serious adverse events. The changes were thought to be mediated, in part, by more efficient oxygen extraction and ventilation.

• Hedlund ER, Lundell B, Soderstrom L, Sjoberg G. Can endurance training improve physical capacity and quality of life in young Fontan patients? Cardiol Young. 2018;28(3):438–46. In this prospective study, pediatric patients with a history of the Fontan procedure completed an endurance training program. Patients improved in their submaximal exercise capacity and quality of life, with gains maintained after 1 year.

Amiard V, Jullien H, Nassif D, Bach V, Maingourd Y, Ahmaidi S. Effects of home-based training at dyspnea threshold in children surgically repaired for congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis. 2008;3(3):191–9.

• Jacobsen RM, Ginde S, Mussatto K, Neubauer J, Earing M, Danduran M. Can a home-based cardiac physical activity program improve the physical function quality of life in children with Fontan circulation? Congenit Heart Dis. 2016;11(2):175–82. In this prospective study, pediatric patients with a history of the Fontan procedure completed a cardiac rehabilitation program for 12 weeks. There were improvements in exercise capacity and parent-reported (but not self-reported) quality of life over time.

Longmuir PE, Tyrrell PN, Corey M, Faulkner G, Russell JL, McCrindle BW. Home-based rehabilitation enhances daily physical activity and motor skill in children who have undergone the Fontan procedure. Pediatr Cardiol. 2013;34(5):1130–51.

Moalla W, Maingourd Y, Gauthier R, Cahalin LP, Tabka Z, Ahmaidi S. Effect of exercise training on respiratory muscle oxygenation in children with congenital heart disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13(4):604–11.

Moalla W, Gauthier R, Maingourd Y, Ahmaidi S. Six-minute walking test to assess exercise tolerance and cardiorespiratory responses during training program in children with congenital heart disease. Int J Sports Med. 2005;26(09):756–62.

Minamisawa S, Nakazawa M, Momma K, Imai Y, Satomi G. Effect of aerobic training on exercise performance in patients after the Fontan operation. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88(6):695–8.

Morrison ML, Sands AJ, McCusker CG, McKeown PP, McMahon M, Gordon J, et al. Exercise training improves activity in adolescents with congenital heart disease. Heart. 2013;99(15):1122–8.

Stieber NA, Gilmour S, Morra A, Rainbow J, Robitaille S, Van Arsdell G, et al. Feasibility of improving the motor development of toddlers with congenital heart defects using a home-based intervention. Pediatr Cardiol. 2012;33(4):521–32.

Patel JN, Kavey RE, Pophal SG, Trapp EE, Jellen G, Pahl E. Improved exercise performance in pediatric heart transplant recipients after home exercise training. Pediatr Transplant. 2008;12(3):336–40.

Newburger JW. Improving neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with congenital heart disease: an intervention study. Boston: Children’s Hospital of Boston; 2018.

•• Cassidy AR, Ilardi D, Bowen SR, Hampton LE, Heinrich KP, Loman MM, et al. Congenital heart disease: a primer for the pediatric neuropsychologist. Child Neuropsychol. 2018;24(7):859–902. This review paper provides an evidence-based, clinically oriented primer on CHDs for pediatric neuropsychologists. The paper provides an introduction to current standard-of-care guidelines for managing children with CHDs, an overview of brain development within the context of CHDs, a summary of typical neuropsychological outcomes and factors influencing variability in outcomes, and a discussion of the implications of past findings and strategies for clinical care.

Puri K, Allen HD, Quereshi AM. Congenital heart disease. Pediatr Rev. 2017;38(10):471–86.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Akamagwuna, U., Badaly, D. Pediatric Cardiac Rehabilitation: a Review. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep 7, 67–80 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40141-019-00216-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40141-019-00216-9