Abstract

Purpose of Review

The acute management of pain using regional anesthesia techniques may prevent the development of persistent postsurgical pain (PPP), ultimately improving patient outcomes and enhancing overall quality of life in postsurgical patients. The purpose of this review is to describe the current literature regarding the role of regional anesthesia techniques in the perioperative setting to address and prevent PPP.

Recent Findings

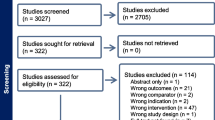

Data was collected and analyzed using results from randomized controlled studies stratified into categories based on different surgical subspecialties. Conclusions were drawn from each surgical category regarding the role of regional anesthesia and/or local analgesia in acute and chronic pain management on the long-term results seen in the studies analyzed.

Summary

Preoperative consultations and optimized perioperative analgesia using regional anesthesia and local analgesia play a fundamental role preventing and treating postoperative pain after many types of surgery by managing pain in the acute setting to mitigate the future development of PPP. Additional studies in different surgical subspecialties are needed to confirm the role regional anesthesia plays in chronic postsurgical pain (CPSP) prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chronic pain is a growing epidemic in the USA, with an estimated 100 million adults currently living with mild to debilitating chronic pain [1]. It has been reported that the number of Americans suffering from chronic pain exceeds the total of Americans with heart disease, cancer, and diabetes combined, the three leading causes of death and disability in the USA according to the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [1, 2]. Persistent postoperative pain (PPP) is a major cause of chronic pain that commonly occurs in patients in the postoperative setting in the months to years following surgery [3••, 4, 5]. This literature review focuses on the role of regional anesthesia to prevent chronic postsurgical pain (CPSP).

The first study on chronic postsurgical pain was published in 1999 by Macrae et al., followed a year later by the first literature review published by Perkins and Kehlet et al. [4, 5]. These early studies were instrumental in uncovering the large individual and societal burden postsurgical pain has become in the USA. One in three to five patients undergoing cardiac surgery, breast surgery, thoracotomy, or limb amputation will experience PPP lasting months to years after surgical intervention [4, 6, 7]. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, 48.3 million ambulatory surgeries were performed in 2010 in the USA, further highlighting the large population at risk [8]. In addition, PPP is challenging to treat, and few treatment modalities exist, thereby making it of paramount importance to prevent acute pain from developing into PPP. As the incidence of PPP after surgery continues to grow, PPP has become a major public health concern [9]. The total cost incurred by American society for all forms of chronic pain is approximately $635 billion per year, and the rapidly rising number of patients suffering from intractable chronic postsurgical pain may be contributing to the current opioid epidemic [1, 3••, 10].

A fundamental element in the understanding of pain is that every chronic pain was once acute [7]. The acute management of pain using regional anesthesia techniques and multi modal analgesia (MMA) may prevent the development of chronic postsurgical pain, ultimately improving patient outcomes and enhancing overall quality of life in postsurgical patients. The purpose of this review is to describe the current literature regarding the role of regional anesthesia techniques in the perioperative setting to address and prevent PPP.

Pain Defined

Pain is defined by The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as, “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” [11••]. According to the IASP, this definition was established in 1979 and revised from 2018 to 2020 to reflect the advances in our understanding of pain. The modified gold standard definition has become widely accepted by health care professionals and researchers in the field of pain, and it has been adopted by various professional, governmental, and nongovernmental organizations, including the World Health Organization [11••]. Clinically, pain exists in two forms: acute and chronic. These are further defined below.

Acute Pain

Acute pain is a dynamic psychophysiological response to tissue trauma and related to the acute inflammatory processes. This occurs in the acute setting in response to tissue injury, inflammation, or disease [1]. The defining feature of this type of pain is its self-limiting nature, resolving within short period of time, or conversion to chronic pain.

Chronic Pain

Chronic pain can be defined as debilitating and possibly indefinite pain that persists past the healing of injured tissue and the related inflammatory processes [1, 3••]. This type of pain can have a devastating impact on patient function and quality of life. Chronic pain syndromes occur when a host of chronic pain symptoms do not respond to the medical model of care. Similarly, PPP is a type of chronic pain syndrome occurring in the postoperative setting and persisting 2 to 3 months after surgery [12, 13]. In the first study published on chronic postsurgical pain, Macrae and Davies et al. proposed a four-point definition for chronic postsurgical pain defining it as, “the pain developed after a surgical procedure; the pain is of at least 2-month duration; other causes for the pain have been excluded; the possibility that the pain is continuing from a pre-existing problem should be explored and exclusion attempted.” Emphasis on the management of PPP in the early perioperative period is crucial, as this can potentially improve patient outcomes, decrease recovery times, and enhance quality of life.

Mechanisms of Chronic Pain

Literature focused on identifying the major cause of PPP has determined that PPP has varied manifestations making it likely to be the product of several overlapping pain mechanisms rather than a single origin [1]. The transition from acute to chronic pain in the postoperative period is complex, controlled by factors such as biomedical, psychosocial, and genetic factors [7].

Biomedical risk factors, such as surgery type, surgical technique, and pain level in the perioperative period, have been identified as major risk factors for the development of PPP in patients [7, 14]. Surgical procedures with the greatest incidence of chronic postsurgical pain are associated with intentional or unintentional nerve damage, as this produces acute and permanent changes in the injured nerves, the intact neighboring nerves, motor and sympathetic outputs, and the pain pathways in the central nervous system, all contributing to chronic neuropathic pain [7, 15]. These surgeries include limb amputation, mastectomy, and thoracotomy [7]. Consequently, it has been reported that upwards of 60 to 70% of patients undergoing amputation, breast surgery (mastectomy), or thoracotomy continue to suffer from chronic pain for months following the procedure [5, 7]. Avoiding intraoperative techniques with the potential to cause nerve damage are important mitigating factors for preventing the development of PPP [4, 5, 16]. Additionally, newer surgical techniques can significantly decrease the incidence of long-term complication following surgery. The introduction of sentinel node biopsies in breast cancer surgery is an example of this. The sentinel node biopsy limits the need for axillary clearance, a major risk factor for neuropathic injury during breast cancer surgery, ultimately decreasing the overall number of patients experiencing neuropathic pain following this procedure [6]. Additionally, a surgeon’s years in practice inversely correlates with incidence of PPP, as more experienced surgeons have been shown to cause less complications and postsurgery pain than those with less surgical experience. Notably, the presence of preoperative pain may be one of the strongest, and most consistent independent risk factors of PPP across a range of surgery types [4, 5, 7].

Psychosocial risk factors are significant factors in the development of PPP [7, 14, 17]. These factors include but are not limited to preoperative anxiety, an introverted personality, catastrophizing, depression, fear of surgery, and psychological inflexibility [7, 18,19,20]. One of the most constant factors related to persistent pain after surgery is anxiety [6]. Kaunisto et al. described the role of anxiety in the perioperative period, showing that patient anxiety at the time of surgery is significantly related to experimental pain sensitivity and acute postoperative pain [21]. Pain catastrophizing is another important factor predicting the development of chronic postsurgical pain [20]. It is defined as a patient’s unrealistic belief that their current situation will ultimately lead to the worst possible pain outcome, ultimately magnifying pain intensity. It has been shown in the literature that patients who do not catastrophize have overall better outcomes than patients who do catastrophize [22, 23]. Psychological inflexibility, or an individual’s inability to act effectively in the presence of unpleasant thoughts or emotions, may also be a central mediator in the transition from acute to chronic pain [14]. A risk assessment tool may have the potential to identify patients preoperatively with mental health factors placing them at high risk of developing PPP. This intervention could play a vital role, allocating these patients to receive preventative interventions prior to surgery to inhibit chronic pain. However, this literature review focuses on regional anesthetic techniques to prevent PPP.

Finally, genetic factors are a newer area of exploration, as it remains largely unknown the exact genetic links that may play a specific role in predicting postoperative pain and PPP [6, 24]. Several studies have linked genetic polymorphisms to acute and chronic postoperative pain states [25, 26]. However, many limitations exist in these studies, including small sample size and lack of duplicated results in larger studies [27]. Future studies with sufficient power to confirm the role of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within target genes, such as the u-opioid receptor, GTP cyclohydrolase, and catecholamine-O-methyltransferase, are of considerable interest, as this would be useful to identify and treat patients at risk for PPP [26, 27]. Furthermore, regarding gender and age, studies have shown that female gender and younger age predict chronic postsurgical pain [7, 20, 28,29,30]. For example, children seem to experience significantly less persistent postsurgery pain as compared to adults [31].

Additional research is needed to study the effectiveness of primary prevention of modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors to reduce the incidence of chronic pain. In most cases, patients have multiple factors that increase the risk of PPP, emphasizing the importance of early identification through a thorough preoperative evaluation and the use of regional anesthesia, local anesthesia, MMA, and psychological interventions when appropriate.

Regional Anesthesia and PPP Prevention

Regional anesthesia may play a role in preventing central sensitization, the molecular mechanism driving the progression from acute to chronic pain in surgical patients. Regional anesthesia is defined as the delivery of local anesthetic close in proximity to a target nerve but at a distance from the surgical site [24]. The role of regional anesthesia and its relationship with interrupting the development of central sensitization is described by Atchabahian et al. in his detailed systematic review [9]. Pain during surgery is triggered by nociceptive input from the primary surgical site, activating a permanent increase in synaptic strength, also called central sensitization. These pathological changes in synaptic transmission from the primary to secondary neuron lead to permanent signal amplification, leading to hyperalgesia and the persistent pain that is often seen after surgery. The role of regional anesthesia in the prevention of central sensitization occurs when an effective nociceptive regional block prevents pain signals from being conducted from the surgical site to the central nervous system, preventing the development of chronic pain and PPP. Therefore, central sensitization cannot occur [9].

An additional area of interest for pain control in the surgical setting is the use of local anesthetics for the prevention of acute and chronic pain. Local anesthesia is an intervention that can be applied locally to the area of interest to interrupt the transmission of pain impulses from the injury site to the central nervous system [9]. Both local and intravenous anesthetics can prevent central sensitization known to cause chronic pain and PPP. This method of pain management can be used alone or in conjunction with regional anesthesia to provide the most effective multimodal pain regimen.

Chronic Pain by Procedure

In this section, we summarize the findings and outcomes of clinical studies by stratifying in broad groups according to surgical procedure. Fifty-three randomized controlled trials (RCT) comparing regional or local anesthesia (by any route) to standard systemic methods of analgesia are included in this literature review. Studies and their regional or local analgesic interventions, including type, timing of intervention, pain outcomes, and follow-up, are summarized in Table 1.

Limb Amputation

Perhaps one of the most common and best described postsurgical chronic pain syndromes is phantom limb pain following limb amputation surgery [1]. The loss of a body part can lead to residual pain, phantom sensations, and phantom pain, contributing to long-term emotional distress and overall diminished quality of life in these patients [32]. Phantom sensations are described as pain-free perceptions arising from the amputated body part after deafferentation, while phantom pain is a painful or unpleasant sensation in the distribution of the lost body part [33]. Phantom pain is identified as a type of PPP, and the reported incidence of phantom limb pain is 30 to 85% in amputees, most commonly occurring in the first 6 months after surgery [33,34,35]. In a 2-year follow-up in amputees, 60% reported phantom limb pain and 21–57% reported residual limb (stump) pain [7]. Since acute residual limb pain is the best overall predictor of chronic residual limb pain in these patients, it is imperative to achieve sufficient perioperative pain control in patients undergoing limb amputation to prevent long-term PPP from developing [36].

Neuraxial anesthesia and peripheral nerve blockade (PNB) are important tools in mitigating and preventing PPP in patients who have undergone limb amputation. Bach et al. found evidence that preoperative lumbar epidural blockade with bupivacaine and morphine reduced the incidence of phantom limb pain in the first year postoperatively compared to controls treated with conventional methods [37]. Several smaller studies have shown that epidural anesthesia and PNB aid in pain reduction during the first week postsurgery by preventing central sensitization, a major contributor to chronic postoperative pain [38, 39]. In patients undergoing lower limb amputation, Sahin et al. found that the use of epidural anesthesia or PNB, rather than conventional general or spinal anesthesia, lead to significantly less pain in the first week after surgery. However, there was no difference in phantom limb pain, phantom sensation, or stump pain at 14 to 17 months post amputation [39]. In another study, Karanikolas et al. showed that the use of perioperative epidural analgesia and/or intravenous PCA reduced phantom limb pain intensity, prevalence, and frequency of 6 months post amputation [40]. Additionally, this RCT validated the use of epidural analgesia in controlling postoperative ischemic and neuropathic pain in the acute setting in this patient population [40]. Katsuly-Liapis et al. confirmed the use of perioperative pain control using neuraxial anesthesia, showing that optimized perioperative analgesia using regional anesthesia techniques can be advantageous in decreasing acute phantom limb pain and PPP in patients who have undergone limb amputation [33].

Breast Surgery

PPP following breast surgery is a major complication, with up to 50% of women complaining of chronic pain following breast surgery, 13% of which is reported to be severe [24, 30, 41]. The incidence of chronic pain occurring after breast surgery increases with invasiveness, with 49% reporting chronic pain following mastectomy with reconstruction, 31% reporting chronic pain following mastectomy, and 22% reporting chronic pain for breast reconstruction [42, 43•]. A literature review examining the use of regional anesthesia techniques in breast surgery included paravertebral block, multimodal block, local infiltration, and a combined brachial plexus block and intercostal block. Additionally, intravenous local anesthetics were included as data has shown to be favorable for the use of local anesthetics for the treatment of pain in breast surgery patients [3••].

Many RCTs have been published in the literature to assess the role of paravertebral block for pain control in the setting of breast cancer surgery to prevent PPP. In a large-scale literature review pooling 18 RCTs with 1297 participants, regional anesthesia was found to promote a reduced risk of PPP after breast cancer surgery [3••]. Of these 18 studies, six studies investigated paravertebral block [44,45,46,47,48,49], four investigated a multimodal block [50,51,52,53], six investigated local infiltration [50, 54,55,56,57,58,59], and two investigated local anesthetics [60, 61]. Overall, the paravertebral block was found to be the superior and favored regional anesthesia technique over conventional methods for the prevention of pain in this population of patients.

The use of intravenous local anesthetics has been shown in the literature to reduce postoperative pain and PPP in patients undergoing breast cancer surgery. Two trials with 97 total participants showed a statistically significant benefit for the use of intravenous local anesthesia to prevent PPP 3 to 6 months after breast cancer surgery (P < 0.05) [60, 61].

Fewer studies have evaluated postoperative regional pain management techniques in cosmetic breast surgery [43•]. The use of TAP blocks for the prevention of chronic pain in patients undergoing breast reconstruction surgery has shown to be successful in several studies. Morphine requirements were lower in the TAP block groups and reduced pain scores acutely [62]. Additional research is needed to evaluate the long-term effects of TAP blocks on PPP in cosmetic breast patients.

In summary, the literature supports the use of regional anesthesia, particularly paravertebral blocks, and local analgesia for women undergoing breast surgery, especially with regards to breast cancer surgery, to decrease postoperative pain acutely and reduce the risk of development of PPP.

Thoracotomy

Up to 80% of patients undergoing thoracic surgery are at risk of experiencing chronic pain. Early and aggressive pain management in the acute setting is crucial for these patients, as there is a strong relationship between the severity of acute postoperative pain and the development of long-term PPP [7, 63, 64••].

Epidural analgesia is regarded as the gold standard for controlling postthoracotomy pain [65]. Several studies in the literature demonstrate the important role of thoracic epidural analgesia in controlling postthoracotomy pain in both the acute and chronic settings [65,66,67,68,69]. Notably, Ju et al. compared two treatments for postthoracotomy pain, thoracic epidural using bupivacaine or intercostal nerve cryoanalgesia (cryo) [65]. Results of the study showed that the cryo group experienced significantly more severe chronic pain interfering with daily life than the thoracic epidural group (P < 0.05). Additionally, the cryo group experienced a higher allodynia-like pain than the thoracic epidural group at 6 and 12 months postoperatively (P < 0.05). A limitation of this study was the use of cryo in place of a placebo, as cryo might worsen neuropathic pain [65]. In another study, Obata et al. examined the role of a preoperative versus postoperative continuous epidural block for tumor patients after thoracotomy. Results at 3 and 6 months after surgery showed that preemptive administration of thoracic epidural ropivacaine and morphine significantly decreased the incidence and duration of PPP [70]. Another study investigated the role of intercostal nerve block using bupivacaine as a form of analgesia [7, 70]. Results found that there was no significant differences in postoperative pain scores between the intercostal nerve block and placebo group 18 months after thoracotomy. However, there are several fundamental limitations that exist in this study, questioning its validity [9]. Finally, Liu et al. sought to describe the role of continuous wound infusion with ropivacaine compared to patient-controlled analgesia with sufentanil for postoperative pain after thoracotomy [71]. The study found that continuous wound infusion with ropivacaine is effective for postoperative pain control. Furthermore, continuous wound infusion may reduce adverse side effects seen during sufentanil pain control such as dizziness, respiratory depression, and drowsiness, decreasing ICU stay and enhancing overall recovery [71]. Regional anesthesia, specifically thoracic epidural analgesia, implemented perioperatively in the setting of thoracotomy has been shown to have a significant reduction in the risk of PPP compared to standard analgesia alone [3••].

Cesarean Section

Regional anesthesia has been shown to markedly reduce the risk of chronic postoperative pain following cesarean section, a novel finding in the development of PPP in this patient population [3••, 24]. Lavand’homme et al. described the continuous intrawound infusion of diclofenac after elective cesarean delivery [72]. This method of pain control was shown to significantly reduce postoperative morphine consumption, and adverse effects compared to saline infusion control with systemic diclofenac pain control describe the transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block with or without adjuvants such as intrathecal morphine and clonidine as a regional technique to manage postcesarean delivery pain [24, 73,74,75,76]. Singh et al. found that the use of TAP blocks as part of a multimodal pain regimen with intrathecal morphine was shown to improve pain scores at 24 h after cesarean section. High-dose TAP blocks may improve pain scores 12 h after cesarean section [73]. Additionally, Loane et al. found that the use of intrathecal morphine versus TAP block was shown to improve pain scores and decrease opioid consumption in patients undergoing cesarean delivery at 2, 6, and 10 h postoperatively [76]. Two studies report numerous advantages to administering a TAP block in conjunction with a multimodal pain regimen, including long-term pain control, decreased opioid consumption, and enhanced recovery postcesarean delivery [24, 77]. Shahin et al. evaluated the effects of intraperitoneal instillation of lidocaine for postcesarean section pain in patients who underwent pariental peritoneal closure [78]. Patients received either 200 mg of intraperitoneal lidocaine or sterile saline and were assessed for pain at every 2 weeks up to 8 months after surgery. Results showed that intraperitoneal lidocaine played a role in decreasing postcesarean pain up to 8 months after surgery [78]. Further studies are warranted for the use of regional analgesia techniques in patients undergoing cesarean section to support our conclusions.

Hysterectomy

Regional anesthesia is a popular alternative to conventional patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) for the prevention of early postoperative pain in vaginal and abdominal hysterectomy. However, there is very limited data on the use of regional analgesia for the prevention of long-term pain and PPP. Spinal anesthesia is a commonly used regional technique in patients undergoing vaginal hysterectomy, ultimately providing optimized pain management and enhanced recovery up to 6 months postoperatively [79, 80]. The use of subarachnoid block anesthesia was found to provide a significantly better postoperative analgesia in the acute setting compared to traditional pain control after vaginal hysterectomy, providing long-term analgesic effects up to 3 months after surgery [81].

Iliac Crest Bone Graft Surgery

Iliac crest bone graft is the gold standard in achieving spinal arthrodesis. Additionally, iliac crest bone graft harvesting (IBGH) is the preferred choice in a number of procedures requiring the use of bone grafts due to its many advantages over other sites [82, 83]. However, harvesting iliac crest bone is an acutely painful procedure, with chronic pain developing in up to 39% of patients [84]. Several studies investigating the role of regional analgesia and local analgesia in preventing acute pain and PPP after iliac crest bone graft harvesting (IBGH) have been described in the literature.

Blumenthal et al. compared ropivacaine to a placebo through an iliac crest catheter after Bankart repair with IBGH [85]. This study demonstrated significantly lower pain and high patient satisfaction in the ropivacaine group compared to placebo up to 3-month postsurgery [85]. Singh et al. performed a similar study delivering either 0.5% Marcaine or normal saline via a continuous infusion catheter placed at the IBGH harvest site in order to determine the long-term effects of postoperative continuous delivery of local anesthetic [86]. The results showed statistically significant decrease in graft site pain score (P < 0.05), significantly improved overall postoperative function and patient satisfaction at a 4-year follow-up (P < 0.05), and significantly reduced chronic dysesthesias (P < 0.05) [86]. Gundes et al. showed favorable results using regional delivery of either bupivacaine alone or combined morphine-bupivacaine at the iliac crest graft site [87]. Results showed that chronic pain and dysesthesia were decreased at a 3-month follow-up for both groups, showing favorable effect on long-term pain in these patients. Additionally, analgesic consumption was shown to be significantly less in the combined morphine-bupivacaine group when compared to bupivacaine alone [87]. Regional anesthesia used perioperatively during IBGH has been shown to have a significant reduction in the risk of PPP.

With regard to pain management using local analgesia, O’Neill et al. study showed that a single local administration of bupivacaine at the iliac crest graft harvest site during posterior spine fusion surgery results in improved overall outcomes and pain scores in the acute and long-term settings [84]. Barkhuysen et al. also investigated the use of local infiltration using a single dose of bupivacaine for pain management during anterior IBGH [83]. In contrast, this study showed no significant differences in postoperative pain acutely between those who received bupivacaine and the control group.

Laparotomy

The role of regional anesthesia in major digestive surgery has been described in very few studies in the literature, each exploring the role of epidural anesthesia for pain management. Lavand’homme et al. found that intraoperative epidural anesthesia in combination with ketamine provides effective preventive pain management after laparotomy [88]. Furthermore, administration of an intraoperative epidural, versus postoperative, was shown to have a greater effect on residual pain in a 1-year follow-up. This study demonstrates a clear benefit to epidural analgesia as a preventative treatment for the development of PPP after major digestive surgery, such as laparotomy. Another study by Katz et al. examined the role of epidural anesthesia in pain outcomes in the acute postoperative setting following laparotomy [89]. Katz et al. showed that patients who received perioperative lumbar epidural experienced significantly less pain at a 3-week follow-up than those who received general anesthesia alone. Longer follow-up was not included.

Hernia Repair

Chronic pain is the most common complication seen after inguinal hernia repair, occurring in up to 30% of patients who undergo this procedure. The persistence of pain at 1 and 4 weeks postoperatively has been linked to chronic pain and PPP [90, 91]. Therefore, optimal pain control in the acute setting is critical in this patient population to prevent chronic pain and PPP from developing. Mounir et al. examined the use of spinal anesthesia for pain control in these patients, concluding that subfascicle infiltration with bupivacaine is effective for decreasing postoperative pain at 3 and 6 months postoperatively [92]. Kurmann et al. evaluated the use of local bupivacaine 0.25% intraoperatively for the prevention of chronic pain after hernia repair [93]. The results of this study found no significant pain differences between the intraoperative infiltration group and the placebo group in the prevention of chronic pain at 3 months postoperatively, favoring conventional postoperative analgesia over local infiltration [93]. This suggests that local analgesia may not play a predominant role in the pain management of inguinal hernia surgery, in contrast to spinal anesthesia.

Prostatectomy

Radical prostatectomy is major treatment choice for prostate cancer, a common cancer in men in the USA [94]. Early and effective pain management in patients undergoing radical retropubic prostatectomy is recommended to prevent moderate to severe postoperative pain from developing in these patients, potentially leading to chronic PPP.

In his RCT, Gupta et al. found evidence for low thoracic epidural analgesia providing superior pain relief and improved expiratory muscle function compared to PCA [94]. Patients received either a low thoracic epidural or patient-controlled intravenous analgesia for postoperative pain control following radical retropubic prostatectomy. Results support the use of thoracic epidural analgesia for optimal pain control in the acute postoperative setting to achieve long-term pain management for radical prostatectomy [94]. In a similar study, Haythornthwaite et al. found no significant difference in pain outcomes in patients who received epidural anesthesia versus traditional analgesia for radical prostatectomy [95]. This study concluded that intraoperative anesthetic technique did not adequately predict the incidence of pain at 3- or 6- month follow-up. Lastly, Brown et al. looked at the role of intrathecal analgesia in patients undergoing radical retropubic prostatectomy [96]. Primary outcome measures of the study included pain and functional status over a 3-week follow-up period in the intrathecal administration. Patients received either general anesthesia and accompanying intravenous fentanyl or general anesthesia preceded by intrathecal administration of bupivacaine 15 mg, clonidine 75 microg, and morphine 0.2 mg. Results of the study showed improved immediate pain scores (18 h postoperatively), decreased opioid requirements in patients who received intrathecal analgesia, and well-controlled pain during the 12-week follow-up. However, there was no significant difference in pain control in the group who received intrathecal analgesia and the control [96].

Vasectomy

One study in the literature supports the role of local anesthesia in vasectomy for acute analgesia and the prevention of PPP. Paxton et al. describes vasectomy syndrome, a common complication of vasectomy, that causes both acute and chronic testicular pain in these patients following the procedure [97]. This study found that infiltration of local bupivacaine into the lumen of the vas deferens is effective in preventing vasectomy syndrome from occurring, as no patients experienced prolonged testicular discomfort in the infiltration group in a 24-week follow-up period [97].

Limitations

Limitations in our study include a restricted number of studies that could be included due to high risk of bias from missing data, small sample sizes, and attrition and data loss, thereby reducing confidence in our findings. Furthermore, clinical heterogeneity, performance bias due to incomplete participant blinding, and sparse outcome data for some surgical groups hindered evidence synthesis. Therefore, additional data is needed in many surgical subspecialties to confirm findings listed in our study.

Conclusions

In the most recent systematic literature review to date, there is evidence validating the role of regional anesthesia to prevent CPSP in the perioperative setting. PPP and CPSP are shown to be devastating and resistant to many forms of treatment, but may be preventable in one out of every four patients with the implementation of regional anesthesia techniques [9]. Results of numerous studies (Table 1) show that perioperative regional anesthesia during breast surgery, thoracotomy, and cesarean section resulted in reduced PPP beyond 3 months postoperatively compared to standard analgesia [3••, 24]. In addition, our literature review noted that regional anesthesia plays a key role in the risk reduction of PPP in limb amputation, hysterectomy, IBGH, laparotomy, hernia repair, and prostatectomy, although more data is needed to support these findings. Preoperative consultations and optimized perioperative analgesia using regional anesthesia and local analgesia play a fundamental role preventing and treating postoperative pain after many types of surgery by identifying patients who are at risk for PPP and managing pain in the acute setting to mitigate the future development of PPP. Additional large-scale prospective randomized studies are needed to further validate the benefits of regional anesthesia and its extended perioperative nociceptive blockade to prevent the development of CPSP in different surgical subgroups.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Chapman CR, Vierck CJ. The transition of acute postoperative pain to chronic pain: an integrative overview of research on mechanisms. J Pain. 2017;18(4):359.

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. “About Chronic Diseases.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 28 April 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/index.htm

Levene JL, Weinstein EJ, Cohen MS, Andreae DA, Chao JY, Johnson M, Hall CB, Andreae MH. Local anesthetics and regional anesthesia versus conventional analgesia for preventing persistent postoperative pain in adults and children: A Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis update. J Clin Anesth. 2019;55:116–27. This Cochrane review, published originally in 2012, was updated in 2017 with new data showing that regional anesthesia may mitigate the risk of persistent postoperative pain (PPP). 40 new and seven ongoing studies were added to the original review, bringing the total included RCTs to 63. Evidence synthesis favored regional anesthesia for thoracotomy, breast cancer surgery, and cesarean section, as well as continuous infusion of local anesthetic after breast cancer surgery.

Perkins FM, Kehlet H. Chronic pain as an outcome of surgery. A review of predictive factors Anesthesiology. 2000;93:1123–33.

Macrae WA. Chronic pain after surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:88–98.

Kalso E. IV. Persistent post-surgery pain: research agenda for mechanisms, prevention, and treatment. British journal of anaesthesia.2013; 111(1), 9–12.

Katz J, Jackson M, Kavanagh BP, Sandler AN. Acute pain after thoracic surgery predicts long-term post-thoracotomy pain. Clin J Pain. 1996;12(1):50–5.

Hall MJ, Schwartzman A, Zhang J, Liu X. Ambulatory surgery data from hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers: United States, 2010. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2017;102:1–15.

Atchabahian A, Andreae M. Long-term functional outcomes after regional anesthesia: a summary of the published evidence and a recent Cochrane Review. Refresh Courses Anesthesiol. 2015;43(1):15–26.

Gaskin DJ, Richard P. The economic costs of pain in the United States. J Pain. 2012;13:715–24.

Raja, S. N., Carr, D. B., Cohen, M., Finnerup, N. B., Flor, H., Gibson, S., Keefe, F. J., Mogil, J. S., Ringkamp, M., Sluka, K. A., Song, X. J., Stevens, B., Sullivan, M. D., Tutelman, P. R., Ushida, T., & Vader, K. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. 2020;161(9). This article provides an important current definition of pain as described by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). The definition of pain was recently revised to match recent advances in our understanding of pain. According to the IASP, the most current definition of pain can be defined as, “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.”

Classification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Prepared by the International Association for the Study of Pain, Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain. Supplement. 1986;3, S1–S226.

Gerner P. Postthoracotomy pain management problems. Anesthesiol Clin. 2008;26(2):355–vii.

Wicksell RK, Olsson GL. Predicting and preventing chronic postsurgical pain and disability. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(6):1260–1.

Devor M, Seltzer Z. Pathophysiology of damaged nerves in relation to chronic pain. In: Textbook of pain. Wall PD, Melzack R (Eds). Churchill Livingstone. 1999;129–164.

Liem MS, van Duyn EB, van der Graaf Y, van Vroonhoven TJ. Recurrences after conventional anterior and laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: a randomized comparison. Ann Surg. 2003;237(1):136–41.

Hinrichs-Rocker A, Schulz K, Jarvinen I, Lefering R, Simanski C, Neugebauer EA. Psychosocial predictors and correlates for chronic post-surgical pain (CPSP): a systematic review. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:719–30.

Peters ML, Sommer M, de Rijke JM, et al. Somatic and psychologic predictors of long-term unfavorable outcome after surgical intervention. Ann Surg. 2007;245(3):487–94.

Borly L, Anderson IB, Bardram L, et al. Preoperative prediction model of outcome after cholecystectomy for symptomatic gallstones. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34(11):1144–52.

Lewis GN, Rice DA, McNair PJ, Kluger M. Predictors of persistent pain after total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(4):551–61.

Kaunisto MA, Jokela R, Tallgren M, Kambur O, Tikkanen E, Tasmuth T, Sipilä R, Palotie A, Estlander AM, Leidenius M, Ripatti S, Kalso EA. Pain in 1,000 women treated for breast cancer: a prospective study of pain sensitivity and postoperative pain. Anesthesiology. 2013;119(6):1410–21.

Sullivan MJL, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, et al. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin J Pain. 2001;17(1):52–64.

Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM, Karoly P. Coping with chronic pain: a critical review of the literature. Pain. 1991;47(3):249–83.

Weinstein EJ, Levene JL, Cohen MS, Andreae DA, Chao JY, Johnson M, et al. Local anaesthetics and regional anaesthesia versus conventional analgesia for preventing persistent postoperative pain in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;6:CD007105

Tegeder, I., Costigan, M., Griffin, R. S., Abele, A., Belfer, I., Schmidt, H., Ehnert, C., Nejim, J., Marian, C., Scholz, J., Wu, T., Allchorne, A., Diatchenko, L., Binshtok, A. M., Goldman, D., Adolph, J., Sama, S., Atlas, S. J., Carlezon, W. A., Parsegian, A., … Woolf, C. J. GTP cyclohydrolase and tetrahydrobiopterin regulate pain sensitivity and persistence. Nature medicine. 2006;12(11), 1269–1277.

Lee PJ, Delaney P, Keogh J, Sleeman D, Shorten GD. Catecholamine-o-methyltransferase polymorphisms are associated with postoperative pain intensity. Clin J Pain. 2011;27(2):93–101.

Montes A, Roca G, Sabate S, Lao Jose I, Navarro Ai, Cantillo J, et al. Genetic and clinical factors associated with chronic postsurgical pain after hernia repair, hysterectomy, and thoracotomy. A two‐year multicenter cohort study. Anesthesiology 2015;122(5):1123‐41.

Kalkman CJ, Visser K, Moen J, et al. Preoperative prediction of severe postoperative pain. Pain. 2003;105(3):415–23.

Thomas T, Robinson C, Champion D, McKell M, Pell M. Prediction and assessment of the severity of post-operative pain and of satisfaction with management. Pain. 1998;75(2–3):177–85.

Poleshuck EL, Katz J, Andrus CH, Hogan LA, Jung BF, Kulick DI, Dworkin RH. Risk factors for chronic pain following breast cancer surgery: a prospective study. J Pain. 2006;7:626–34.

Kristensen AD, Ahlburg P, Lauridsen MC, Jensen TS, Nikolajsen L. Chronic pain after inguinal hernia repair in children. Br J Anaesth. 2012;109:603–8.

Hsu E, Cohen SP. Postamputation pain: epidemiology, mechanisms, and treatment. J Pain Res. 2013;6:121–36.

Katsuly-Liapis I, Georgakis P, Tierry C. Preemptive extradural analgesia reduces the incidence of phantom pain in lower limb amputees. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76:125.

Niraj G, Rowbotham DJ. Persistent postoperative pain: where are we now? Br J Anaesth. 2011;107:25–9.

Perkins FM, Kehlet H. Chronic pain after surgery: a review of predictive factors. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:1123–33.

Hanley MA, Jensen MP, Smith DG, Ehde DM, Edwards WT, Robinson LR. Preamputation pain and acute pain predict chronic pain after lower extremity amputation. J Pain. 2007;8(2):102–9.

Bach S, Noreng MF, Tjéllden NU. Phantom limb pain in amputees during the first 12 months following limb amputation, after preoperative lumbar epidural blockade. Pain. 1988;33(3):297–301.

Ong BY, Arneja A, Ong EW. Effects of anesthesia on pain after lower-limb amputation. J Clin Anesth. 2006;18:600–4.

Sahin SH, Colak A, Arar C, Tutunculer E, Sut N, Y©¥lmaz B, et al. A retrospective trial comparing the effects of different anesthetic techniques on phantom pain after lower limb amputation. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2011;72:127–37.

Karanikolas M, Aretha D, Tsolakis I, Monantera G, Kiekkas P, Papadoulas S, et al. Optimized perioperative analgesia reduces chronic phantom limb pain intensity, prevalence, and frequency: a prospective, randomized, clinical trial. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:1144–54.

Gärtner R, Jensen MB, Nielsen J, Ewertz M, Kroman N, Kehlet H. Prevalence of and factors associated with persistent pain following breast cancer surgery. JAMA. 2009;302(18):1985–92.

Wallace MS, Wallace AM, Lee J, Dobke MK. Pain after breast surgery: a survey of 282 women. Pain. 1996;66(2–3):195–205.

Urits I, Lavin C, Patel M, et al. Chronic pain following cosmetic breast surgery: a comprehensive review. Pain Ther. 2020;9(1):71–82. This comprehensive literature review provides evidence that regional anesthetic strategies can improve chronic postoperative pain outcomes in cosmetic breast surgery. It is the most recent review to date providing evidence from multiple RCTs and systematic reviews showing efficacy of effectiveness of preventative pain strategies.

Kairaluoma PM, Bachmann MS, Rosenberg PH, Pere PJ. Preincisional paravertebral block reduces the prevalence of chronic pain after breast surgery. Anesth Analg. 2006;103(3):703–8.

Ibarra MM, S-Carralero GC, Vicente GU, Cuartero del Pozo A, López Rincón R, Fajardo del Castillo MJ. Chronic postoperative pain after general anesthesia with or without a single-dose preincisional paravertebral nerve block in radical breast cancer surgery. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2011 May;58(5):290–4.

Lee, P. & McAuliffe, N. & Dunlop, C. & Palanisamy, Mahesh & Shorten, George. A comparison of the effects of two analgesic regimens on the development of persistent post-surgical pain (PPSP) after breast surgery. Jurnalul Roman de Anestezie Terapie Intensiva/Romanian Journal of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 2013;20. 83–93.

Karmakar MK, Samy W, Li JW, Lee A, Chan WC, Chen PP, Ho AM. Thoracic paravertebral block and its effects on chronic pain and health-related quality of life after modified radical mastectomy. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2014;39(4):289–98.

Lam D, Green J, Henschke S, Cameron J, Hamilton S, Van Wiingaarden-Stephens M, et al.Paravertebral block vs. sham in the setting of a multimodal analgesia regimen and total intravenous anesthesia for mastectomy: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. 40th Annu. Reg. Anesthesiol. Acute Pain Med. Meet, 2015.

Gacio MF, Lousame AMA, Pereira S, Castro C, Santos J. Paravertebral block for management of acute postoperative pain and intercostobrachial neuralgia in major breast surgery. Brazilian J Anesthesiol. 2016;66:475–84.

Fassoulaki A, Triga A, Melemeni A, Sarantopoulos C. Multimodal analgesia with gabapentin and local anesthetics prevents acute and chronic pain after breast surgery for cancer. Anesth Analg. 2005;101(5):1427–32.

Micha G, Vassi A, Balta M, Panagiotidou O, Saleh M, Chondreli S. The effect of local infiltration of ropivacaine on the incidence of chronic neuropathic pain after modified radical mastectomy. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2012;29:199.

Albi-Feldzer A, Mouret-Fourme EE, Hamouda S, Motamed C, Dubois PY, Jouanneau L, et al. A double-blind randomized trial of wound and intercostal space infiltration with ropivacaine during breast cancer surgery: effects on chronic postoperative pain. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(2):318–26.

Tecirli AT, Inan N, Inan G, Kurukahveci O, Kuruoz S. The effects of intercostobrachial nerve block on acute and chronic pain after unilateral mastectomy and axillary lymph node dissection surgery. Pain Pract. 2014;14:63.

Fassoulaki A, Sarantopoulos C, Melemeni A, Hogan Q. EMLA reduces acute and chronic pain after breast surgery for cancer. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2000;25(4):350–5.

Baudry G, Steghens A, Laplaza D, Koeberle P, Bachour K, Bettinger G, et al. Ropivacaine infiltration during breast cancer surgery: postoperative acute and chronic pain effect. Annales Françaises d’Anesthésie et de Réanimation. 2008;27(1769‐6623 (Electronic), 12):979‐86.

Strazisar B, Besic N. Comparison of continuous local anesthetic and systemic pain treatment after axillary lymphadenectomy in breast carcinoma patients—a prospective randomized study—final results. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2012;37(5):E218.

Fassoulaki A, Sarantopoulos C, Melemeni A, Hogan Q. Regional block and mexiletine: the effect on pain after cancer breast surgery. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2001;26:223–8.

Besic N, Strazisar B. Incidence of chronic pain after continuous local anesthetic in comparison to standard systemic pain treatment after axillary lymphadenectomy or primary reconstruction with a tissue expander in breast carcinoma patients: a prospective randomized study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(1):S47-8.

Strazisar B, Besic N. Continuous infusion of local anesthetic into surgical wound after breast cancer operations efficiently reduces pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2014;39(5): e219.

Grigoras A, Lee P, Sattar F, Shorten G. Perioperative intravenous lidocaine decreases the incidence of persistent pain after breast surgery. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(7):567–72.

Terkawi AS, Sharma S, Durieux ME, Thammishetti S, Brenin D, Tiouririne M. Perioperative lidocaine infusion reduces the incidence of post-mastectomy chronic pain: a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial. Pain Physician. 2015;18(2):E139-46.

Oh J, Pagé MG, Zhong T, McCluskey S, Srinivas C, O’Neill AC, Kahn J, Katz J, Hofer SOP, Clarke H. Chronic postsurgical pain outcomes in breast reconstruction patients receiving perioperative transversus abdominis plane catheters at the donor site: a prospective cohort follow-up study. Pain Pract. 2017;17(8):999–1007.

Maguire MF, Ravenscroft A, Beggs D, Duffy JP. A questionnaire study investigating the prevalence of the neuropathic component of chronic pain after thoracic surgery. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2006;29(5):800–5.

Gupta, R., Van de Ven, T., & Pyati, S. Post-thoracotomy pain: current strategies for prevention and treatment. Drugs. 2020;1677–1684;80(16). This article is the most current study examining acute multimodal pain management to prevent the development of chronic post-thoracotomy pain syndrome (PTPS) after thoracotomy surgery. This study provides evidence that effective acute pain management using a multimodal technique can result in decreased incidence of PTPS.

Ju H, Feng Y, Yang BX, Wang J. Comparison of epidural analgesia and intercostal nerve cryoanalgesia for post-thoracotomy pain control. Eur J Pain. 2008;12(3):378–84.

Lu YL, Wang XD, Lai RC, Huang W, Xu M. Correlation of acute pain treatment to occurrence of chronic pain in tumor patients after thoracotomy. Aizheng. 2008;27:206–9.

Sentürk, M., Ozcan, P. E., Talu, G. K., Kiyan, E., Camci, E., Ozyalçin, S., Dilege, S., & Pembeci, K. The effects of three different analgesia techniques on long-term postthoracotomy pain. Anesthesia and analgesia,. 2002;94(1).

Can A, Erdem AF, Aydin Y, Ahiskalioglu A, Kursad H. The effect of preemptive thoracic epidural analgesia on long-term wound pain following major thoracotomy. Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences. 2013;43(4):515–20.

Comez M, Celik M, Dostbil A, Aksoy M, Ahiskalioglu A, Erdem AF, et al. The effect of pre-emptive intravenous dexketoprofen + thoracal epidural analgesia on the chronic post-thoracotomy pain. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(5):8101–7.

Obata, H., Saito, S., Fujita, N., Fuse, Y., Ishizaki, K., & Goto, F. Epidural block with mepivacaine before surgery reduces long-term post-thoracotomy pain. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia, 46(12), 1127–1132. Kavanagh, B. P., Katz, J., Sandler, A. N., Nierenberg, H., Roger, S., Boylan, J. F., & Laws, A. K. Multimodal analgesia before thoracic surgery does not reduce postoperative pain. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1999; 73(2), 184–189.

Liu FF, Liu XM, Liu XY, Tang J, Jin L, Li WY, Zhang LD. Postoperative continuous wound infusion of ropivacaine has comparable analgesic effects and fewer complications as compared to traditional patient-controlled analgesia with sufentanil in patients undergoing non-cardiac thoracotomy. International Journal of Clinical And Experimental Medicine. 2015;8(4):5438–45.

Lavand’homme PM, Roelants F, Waterloos H, De Kock MF. Postoperative analgesic effects of continuous wound infiltration with diclofenac after elective cesarean delivery. Anesthesiology. 2007; 106: 1220–5

Singh K, Phillips FM, Kuo E, Campbell M. A prospective, randomized, double-blind study of the efficacy of postoperative continuous local anesthetic infusion at the iliac crest bone graft site after posterior spinal arthrodesis: a minimum of 4-year follow-up. Spine. 2007;32(25):2790–6.

McKeen DM, George RB, Boyd JC, Allen VM, Pink A. Transversus abdominis plane block does not improve early or late pain outcomes after Cesarean delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Can J Anesth. 2014;61:631–40.

Bollag L, Richebe P, Siaulys M, Ortner CM, Gofeld M, Landau R. Effect of transversus abdominis plane block with and without clonidine on post-cesarean delivery wound hyperalgesia and pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2012;37:508–14.

Loane H, Preston R, Douglas MJ, Massey S, Papsdorf M, Tyler J. A randomized controlled trial comparing intrathecal morphine with transversus abdominis plane block for post-cesarean delivery analgesia. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2012;21(2):112–8.

Brogi E, Kazan R, Cyr S, Giunta F, Hemmerling TM. Transversus abdominal plane block for postoperative analgesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Can J Anaesth. 2016;63(10):1184–96.

Shahin AY, Osman AM. Intraperitoneal lidocaine instillation and postcesarean pain after parietal peritoneal closure: a randomized double blind placebo-controlled trial. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(2):121–7.

Purwar B, Ismail KM, Turner N, Farrell A, Verzune M, Annappa M, et al. General or spinal anaesthetic for vaginal surgery in pelvic floor disorders (GOSSIP): a feasibility randomised controlled trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(8):1171–8.

Wodlin NB, Nilsson L, Arestedt K, Kjolhede P. Mode of anesthesia and postoperative symptoms following abdominal hysterectomy in a fast-track setting. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90(4):369–79.

Sprung J, Sanders MS, Warner ME, Gebhart JB, Stanhope CR, Jankowski CJ, Liedl L, Schroeder DR, Brown DR, Warner DO. Pain relief and functional status after vaginal hysterectomy: intrathecal versus general anesthesia. Can J Anaesth. 2006;53(7):690–700.

Ahlmann E, Patzakis M, Roidis N, Shepherd L, Holtom P. Comparison of anterior and posterior iliac crest bone grafts in terms of harvest-site morbidity and functional outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:716–20.

Barkhuysen R, Meijer GJ, Soehardi A, Merkx MA, Borstlap WA, Berge SJ, et al. The effect of a single dose of bupivacaine on donor site pain after anterior iliac crest bone harvesting. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:260–5.

O’Neill KR, Lockney DT, Bible JE, Crosby CG, Devin CJ. Bupivacaine for pain reduction after iliac crest bone graft harvest. Orthopedics. 2014;37(5):e428–34.

Blumenthal S, Dullenkopf A, Rentsch K, Borgeat A. Continuous infusion of ropivacaine for pain relief after iliac crest bone grafting for shoulder surgery. Anesthesiology. 2005;102(2):392–7.

Singh S, Dhir S, Marmai K, Rehou S, Silva M, Bradbury C. Efficacy of ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane blocks for post-cesarean delivery analgesia: a double-blind, dose-comparison, placebo-controlled randomized trial. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2013;22(3):188–93.

Gündeş H, Kiliçkan L, Gürkan Y, Sarlak A, Toker K. Short- and long-term effects of regional application of morphine and bupivacaine on the iliac crest donor site. Acta Orthop Belg. 2000;66(4):341–4.

Lavand’homme, P., De Kock, M., & Waterloos, H. Intraoperative epidural analgesia combined with ketamine provides effective preventive analgesia in patients undergoing major digestive surgery. Anesthesiology. 2005;103(4), 813–820.

Katz J, Cohen L. Preventive analgesia is associated with reduced pain disability 3 weeks but not 6 months after major gynecologic surgery by laparotomy. Anesthesiology. 2004;101(1):169–74.

Honigmann P, Fischer H, Kurmann A, Audige L, Schupfer G, Metzger J. Investigating the effect of intra‐operative infiltration with local anaesthesia on the development of chronic postoperative pain after inguinal hernia repair. A randomized placebo controlled triple blinded and group sequential study design. BMC surgery. 2007;7:22.

Callesen T, Bech K, Kehlet H. Prospective study of chronic pain after groin hernia repair. Br J Surg. 1999;86(12):1528–31.

Mounir K, Bensghir M, Elmoqaddem A, Massou S, Belyamani L, Atmani M, Azendour H, DrissiKamili N. Efficiency of bupivacaine wound subfasciale infiltration in reduction of postoperative pain after inguinal hernia surgery. Annales francaises d’anesthesie et de reanimation. 2010;29(4):274–8.

Kurmann A, Fischer H, Dell-Kuster S, Rosenthal R, Audigé L, Schüpfer G, Metzger J, Honigmann P. Effect of intraoperative infiltration with local anesthesia on the development of chronic pain after inguinal hernia repair: a randomized, triple-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Surgery. 2015;157(1):144–54.

Gupta A, Fant F, Axelsson K, Sandblom D, Rykowski J, Johansson JE, Andersson SO. Postoperative analgesia after radical retropubic prostatectomy: a double-blind comparison between low thoracic epidural and patient-controlled intravenous analgesia. Anesthesiology. 2006;105(4):784–93.

Haythornthwaite JA, Raja SN, Fisher B, Frank SM, Brendler CB, Shir Y. Pain and quality of life following radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol. 1998;160(5):1761–4.

Brown DR, Hofer RE, Patterson DE, Fronapfel PJ, Maxson PM, Narr BJ, Eisenach JH, Blute ML, Schroeder DR, Warner DO. Intrathecal anesthesia and recovery from radical prostatectomy: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2004;100(4):926–34.

Paxton LD, Huss BK, Loughlin V, Mirakhur RK. Intra-vas deferens bupivacaine for prevention of acute pain and chronic discomfort after vasectomy. Br J Anaesth. 1995;74:612–3.

Batdorf NJ, Lemaine V, Lovely JK, Ballman KV, Goede WJ, Martinez-Jorge J, Booth-Kowalczyk AL, Grubbs PL, Bungum LD, Saint-Cyr M. Enhanced recovery after surgery in microvascular breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg. 2015;68(3):395–402.

Andreae MH, Andreae DA. Regional anaesthesia to prevent chronic pain after surgery: a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(5):711–20.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Regional Anesthesia.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kukreja, P., Paul, L.M., Sellers, A.R. et al. The Role of Regional Anesthesia in the Development of Chronic Pain: a Review of Literature. Curr Anesthesiol Rep 12, 417–438 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40140-022-00536-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40140-022-00536-y