Abstract

Purpose of Review

From 2018 to 2019, several international pediatric anesthesia societies challenged the current fasting guidelines, moving to decrease the fasting increment for clear liquids to 1 hour (h). Both the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) and the Society for Pediatric Anesthesia (SPA) have hesitated to change, citing insufficient support. We sought to better understand the evidence related to fasting in children.

Recent Findings

We reviewed the literature from the past 5 years and conducted an informal survey of 51 United States (US) pediatric medical centers. Some medical institutions in the US caring for children have implemented policies to mirror the international guidelines. Our search revealed many patient, family, and system reasons to move to a shorter clear fluid fasting period. However, some medical conditions create increased risk of aspiration.

Summary

Available evidence supports a shorter fasting period, but individual patient factors should be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Available on request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration: application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures: a report by the American Society of Anesthesiologist Task Force on Preoperative Fasting. Anesthesiology. 1999;90(3):896–905.

Practice Guidelines for Preoperative Fasting and the Use of Pharmacologic Agents to Reduce the Risk of Pulmonary Aspiration: Application to Healthy Patients Undergoing Elective Procedures: An Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preoperative Fasting and the Use of Pharmacologic Agents to Reduce the Risk of Pulmonary Aspiration. Anesthesiology. 2017;126(3):376–93.

Kelly CJ, Walker RW. Perioperative pulmonary aspiration is infrequent and low risk in pediatric anesthetic practice. Paediatr Anaesth. 2015;25(1):36–43.

Tan Z, Lee SY. Pulmonary aspiration under GA: a 13-year audit in a tertiary pediatric unit. Paediatr Anaesth. 2016;26(5):547–52.

Walker RW. Pulmonary aspiration in pediatric anesthetic practice in the UK: a prospective survey of specialist pediatric centers over a one-year period. Paediatr Anaesth. 2013;23(8):702–11.

Warner MA, Warner ME, Warner DO, Warner LO, Warner EJ. Perioperative pulmonary aspiration in infants and children. Anesthesiology. 1999;90(1):66–71.

Borland LM, Sereika SM, Woelfel SK, Saitz EW, Carrillo PA, Lupin JL, et al. Pulmonary aspiration in pediatric patients during general anesthesia: incidence and outcome. J Clin Anesth. 1998;10(2):95–102.

Habre W, Disma N, Virag K, Becke K, Hansen TG, Jöhr M, et al. Incidence of severe critical events in paediatric anaesthesia (APRICOT): a prospective multicentre observational study in 261 hospitals in Europe. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(5):412–25.

Andersson H, Zarén B, Frykholm P. Low incidence of pulmonary aspiration in children allowed intake of clear fluids until called to the operating suite. Paediatr Anaesth. 2015;25(8):770–7.

Newton RJG, Stuart GM, Willdridge DJ, Thomas M. Using quality improvement methods to reduce clear fluid fasting times in children on a preoperative ward. Paediatr Anaesth. 2017;27(8):793–800.

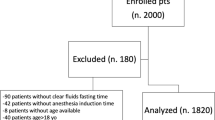

•• Beach ML, Cohen DM, Gallagher SM, Cravero JP. Major Adverse Events and Relationship to Nil per Os Status in Pediatric Sedation/Anesthesia Outside the Operating Room: A Report of the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium. Anesthesiology. 2016;124(1):80–8. This prospective, observational multicenter study utilized data from the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium and showed that NPO status was not an independent predictor of aspiration or major adverse events.

Dennhardt N, Beck C, Huber D, Sander B, Boehne M, Boethig D, et al. Optimized preoperative fasting times decrease ketone body concentration and stabilize mean arterial blood pressure during induction of anesthesia in children younger than 36 months: a prospective observational cohort study. Paediatr Anaesth. 2016;26(8):838–43.

Schreiner MS, Triebwasser A, Keon TP. Ingestion of liquids compared with preoperative fasting in pediatric outpatients. Anesthesiology. 1990;72(4):593–7.

Castillo-Zamora C, Castillo-Peralta LA, Nava-Ocampo AA. Randomized trial comparing overnight preoperative fasting period Vs oral administration of apple juice at 06:00–06:30 am in pediatric orthopedic surgical patients. Paediatr Anaesth. 2005;15(8):638–42.

Splinter WM, Stewart JA, Muir JG. The effect of preoperative apple juice on gastric contents, thirst, and hunger in children. Can J Anaesth. 1989;36(1):55–8.

Rosen D, Gamble J, Matava C. Canadian Pediatric Anesthesia Society statement on clear fluid fasting for elective pediatric anesthesia. Can J Anaesth. 2019;66(8):991–2.

Linscott D. SPANZA endorses 1-hour clear fluid fasting consensus statement. Paediatr Anaesth. 2019;29(3):292.

Imeokparia F, Johnson M, Thakkar RK, Giles S, Capello T, Fabia R. Safety and efficacy of uninterrupted perioperative enteral feeding in pediatric burn patients. Burns. 2018;44(2):344–9.

•• Schmidt AR, Buehler KP, Both C, Wiener R, Klaghofer R, Hersberger M, et al. Liberal fluid fasting: impact on gastric pH and residual volume in healthy children undergoing general anaesthesia for elective surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121(3):647–55. This prospective, randomized study compared liberal fasting with standard NPO guidelines. The authors found that liberal clear fluid intake until premedication significantly decreased actual NPO times but did not impact residual gastric volume or pH, unless fasting times were less than 30 minutes.

Ohashi Y, Walker JC, Zhang F, Prindiville FE, Hanrahan JP, Mendelson R, et al. Preoperative gastric residual volumes in fasted patients measured by bedside ultrasound: a prospective observational study. Anaesth Intens Care. 2018;46(6):608–13.

Andersson H, Schmitz A, Frykholm P. Preoperative fasting guidelines in pediatric anesthesia: are we ready for a change? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2018;31(3):342–8.

Desgranges FP, Gagey Riegel AC, Aubergy C, de Queiroz SM, Chassard D, Bouvet L. Ultrasound assessment of gastric contents in children undergoing elective ear, nose and throat surgery: a prospective cohort study. Anaesthesia. 2017;72(11):1351–6.

Presta MV, Bhavani SS, Abdelmalak BB. Nil per os guidelines: what is changing, what is not, and what should? Minerva Anestesiol. 2018;84(12):1413–9.

Frykholm P, Schindler E, Sümpelmann R, Walker R, Weiss M. Preoperative fasting in children: review of existing guidelines and recent developments. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120(3):469–74.

Nguyen-Buckley C, Wong M. Anesthesia for Intestinal Transplantation. Anesthes Clin. 2017;35(3):509–21.

Friedrich S, Meybohm P, Kranke P. Nulla Per Os (NPO) guidelines: time to revisit? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2020;33(6):740–5.

Thomas M, Morrison C, Newton R, Schindler E. Consensus statement on clear fluids fasting for elective pediatric general anesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2018;28(5):411–4.

Fawcett WJ, Thomas M. Pre-operative fasting in adults and children: clinical practice and guidelines. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(1):83–8.

Parekh UR, Rajan N, Iglehart RC, McQuillan PM. Bedside ultrasound assessment of gastric content in children noncompliant with preoperative fasting guidelines: Is it time to include this in our practice? Saudi J Anaesth. 2018;12(2):318–20.

Green SM, Leroy PL, Roback MG, Irwin MG, Andolfatto G, Babl FE, et al. An international multidisciplinary consensus statement on fasting before procedural sedation in adults and children. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(3):374–85.

Dudaryk R, Epstein RH, Varon AJ. Nil Per Os Consideration for Emergency Procedures: Cornerstone of Safety or an Obstacle to Patient Care? Anesth Analg. 2018;127(3):799–801.

Toms AS, Rai E. Operative fasting guidelines and postoperative feeding in paediatric anaesthesia-current concepts. Indian J Anaesth. 2019;63(9):707–12.

•• Pfaff KE, Tumin D, Miller R, Beltran RJ, Tobias JD, Uffman JC. Perioperative aspiration events in children: A report from the Wake Up Safe Collaborative. Paediatr Anaesth. 2020;30(6):660–6. This large, retrospective study utilized a multi-institutional registry to identify risk factors for pulmonary aspiration. They found an overall incidence of 0.006% and risk factors were emergency surgery and higher ASA status.

Kovacic K, Elfar W, Rosen JM, Yacob D, Raynor J, Mostamand S, et al. Update on pediatric gastroparesis: A review of the published literature and recommendations for future research. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(3):e13780.

Kouvarellis AJ, Van der Spuy K, Biccard BM, Wilson G. A prospective study of paediatric preoperative fasting times at Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2020;110(10):1026–31.

Kotfis K, Jamioł-Milc D, Skonieczna-Żydecka K, Folwarski M, Stachowska E. The Effect of Preoperative Carbohydrate Loading on Clinical and Biochemical Outcomes after Cardiac Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Nutrients. 2020;12(10).

•• Beck CE, Rudolph D, Mahn C, Etspüler A, Korf M, Lüthke M, et al. Impact of clear fluid fasting on pulmonary aspiration in children undergoing general anesthesia: Results of the German prospective multicenter observational (NiKs) study. Paediatr Anaesth. 2020;30(8):892–9. This large, prospective, multicenter study showed that changing fasting times from two hours to one hour for clear liquids does not change the incidence of pulmonary aspiration.

Al-Robeye AM, Barnard AN, Bew S. Thirsty work: Exploring children’s experiences of preoperative fasting. Paediatr Anaesth. 2020;30(1):43–9.

•• Andersson H, Hellström PM, Frykholm P. Introducing the 6-4-0 fasting regimen and the incidence of prolonged preoperative fasting in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2018;28(1):46–52. This prospective cohort study looked at duration of NPO times in children with standard fasting compared with liberal guidelines. They found that the median fasting times were decreased from 4 hours with standard fasting to one hour with 6-4-0 fasting guidelines.

McCann ME, Lee JK, Inder T. Beyond Anesthesia Toxicity: Anesthetic Considerations to Lessen the Risk of Neonatal Neurological Injury. Anesth Analg. 2019;129(5):1354–64.

Dennhardt N, Beck C, Huber D, Nickel K, Sander B, Witt LH, et al. Impact of preoperative fasting times on blood glucose concentration, ketone bodies and acid-base balance in children younger than 36 months: A prospective observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015;32(12):857–61.

• Simpao AF, Wu L, Nelson O, Gálvez JA, Tan JM, Wasey JO, et al. Preoperative Fluid Fasting Times and Postinduction Low Blood Pressure in Children: A Retrospective Analysis. Anesthesiology. 2020;133(3):523–33. This retrospective, cohort study looked at clear fasting times and hypotension in children. The authors found that prolonged clear fluid fasting time was associated with increased risk of low blood pressure during general anesthesia.

Weinstein DA, Steuerwald U, De Souza CFM, Derks TGJ. Inborn Errors of Metabolism with Hypoglycemia: Glycogen Storage Diseases and Inherited Disorders of Gluconeogenesis. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2018;65(2):247–65.

Rui L. Energy metabolism in the liver. Compr Physiol. 2014;4(1):177–97.

Gottlieb EA, Andropoulos DB. Anesthesia for the patient with congenital heart disease presenting for noncardiac surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthes. 2013;26(3):318–26.

Brockel MA, Kenny MC, Sevick CJ, Vemulakonda VM. The role of preoperative instructions in parents’ understanding of preoperative fasting for outpatient pediatric urology procedures. Pediatr Surg Int. 2020;36(9):1111–6.

Billings KR, Schneider AL, Safri S, Kauffunger L, Valika T. Patient factors associated with NPO violations in a tertiary care pediatric otolaryngology practice. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2020;5(6):1227–32.

Khanna P, Saini K, Sinha R, Nisa N, Kumar S, Maitra S. Correlation between duration of preoperative fasting and emergence delirium in pediatric patients undergoing ophthalmic examination under anesthesia: A prospective observational study. Paediatr Anaesth. 2018;28(6):547–51.

Radtke FM, Franck M, Hagemann L, Seeling M, Wernecke KD, Spies CD. Risk factors for inadequate emergence after anesthesia: emergence delirium and hypoactive emergence. Minerva Anestesiol. 2010;76(6):394–403.

Beck CE, Rudolp D, Becke-Jakob K, Schindler E, Etspüler A, Trapp A, et al. Real fasting times and incidence of pulmonary aspiration in children: Results of a German prospective multicenter observational study. Paediatr Anaesth. 2019;29(10):1040–5.

Spencer AO, Walker AM, Yeung AK, Lardner DR, Yee K, Mulvey JM, et al. Ultrasound assessment of gastric volume in the fasted pediatric patient undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: development of a predictive model using endoscopically suctioned volumes. Paediatr Anaesth. 2015;25(3):301–8.

http://www2.pedsanesthesia.org/meetings/2012ia/syllabus/submissions/abstracts/NON-182.pdf. Society of Pediatric Anesthesia; 2012. Accessed 23 June 2021.

Gagey AC, de Queiroz SM, Desgranges FP, Combet S, Naulin C, Chassard D, et al. Ultrasound assessment of the gastric contents for the guidance of the anaesthetic strategy in infants with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: a prospective cohort study. Br J Anaesth. 2016;116(5):649–54.

McCracken GC, Montgomery J. Postoperative nausea and vomiting after unrestricted clear fluids before day surgery: A retrospective analysis. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2018;35(5):337–42.

Disma N, Thomas M, Afshari A, Veyckemans F, De Hert S. Clear fluids fasting for elective paediatric anaesthesia: The European Society of Anaesthesiology consensus statement. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2019;36(3):173–4.

Andersson H, Frykholm P. Gastric content assessed with gastric ultrasound in paediatric patients prescribed a light breakfast prior to general anaesthesia: A prospective observational study. Paediatr Anaesth. 2019;29(12):1173–8.

Lee JJ, Price JC, Duren A, Shertzer A, Hannum R, Akita FA, et al. Ultrasound Evaluation of Gastric Emptying Time in Healthy Term Neonates after Formula Feeding. Anesthesiology. 2021;134(6):845–51.

•• Isserman R, Elliott E, Subramanyam R, Kraus B, Sutherland T, Madu C, et al. Quality improvement project to reduce pediatric clear liquid fasting times prior to anesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2019;29(7):698–704. A single center study utilizing QI methodology to optimize NPO status with a 6-4-0 guideline in a U.S. institution.

• Beck CE, Chandrakumar T, Sümpelmann R, Nickel K, Keil O, Heiderich S, et al. Ultrasound assessment of gastric emptying time after intake of clear fluids in children scheduled for general anesthesia-A prospective observational study. Paediatr Anaesth. 2020;30(12):1384–9. This prospective, observational study looked at gastric emptying time of clear fluids in children preoperatively. The study found a mean gastric emptying time of less than 1 hour after drinking <5 ml/kg of clear fluids.

Engelhardt T, Wilson G, Horne L, Weiss M, Schmitz A. Are you hungry? Are you thirsty?–fasting times in elective outpatient pediatric patients. Paediatr Anaesth. 2011;21(9):964–8.

Bouvet L, Loubradou E, Desgranges FP, Chassard D. Effect of gum chewing on gastric volume and emptying: a prospective randomized crossover study. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119(5):928–33.

Ouanes JP, Bicket MC, Togioka B, Tomas VG, Wu CL, Murphy JD. The role of perioperative chewing gum on gastric fluid volume and gastric pH: a meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2015;27(2):146–52.

Lambert E, Carey S. Practice Guideline Recommendations on Perioperative Fasting: A Systematic Review. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;40(8):1158–65.

Liangthanasarn P, Nemet D, Sufi R, Nussbaum E. Therapy for pulmonary aspiration of a polyethylene glycol solution. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37(2):192–4.

Mosquera RA, McDonald M, Samuels C. Aspiration pneumonitis caused by polyethylene glycol-electrolyte solution treated with conservative management. Case Rep Pediatr. 2014;2014:872634.

Mahmoud M, McAuliffe J, Donnelly LF. Administration of enteric contrast material before abdominal CT in children: current practices and controversies. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41(4):409–12.

Berger-Achituv S, Zissin R, Shenkman Z, Gutermacher M, Erez I. Gastric emptying time of oral contrast material in children and adolescents undergoing abdominal computed tomography. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51(1):31–4.

Kharazmi SA, Kamat PP, Simoneaux SF, Simon HK. Violating traditional NPO guidelines with PO contrast before sedation for computed tomography. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29(9):979–81.

[Beth Israel Deaconness Medical Center Oral Contrast Guidelines]. Available from: https://anesthesia.bidmc.harvard.edu/Policies/Clinical/Clinical/Guidelines/Fasting%20Recommendations%20for%20Patients%20Receiving%20Sedation%20or%20Anesthesia.pdf. Accessed 23 June 2021.

Agrawal D, Marull J, Tian C, Rockey DC. Contrasting Perspectives of Anesthesiologists and Gastroenterologists on the Optimal Time Interval between Bowel Preparation and Endoscopic Sedation. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:497176.

Boretsky K. Perioperative Point-of-Care Ultrasound in Children. Children (Basel). 2020;7(11).

Singla K, Bala I, Jain D, Bharti N, Samujh R. Parents’ perception and factors affecting compliance with preoperative fasting instructions in children undergoing day care surgery: A prospective observational study. Indian J Anaesth. 2020;64(3):210–5.

Sümpelmann R, Becke K, Zander R, Witt L. Perioperative fluid management in children: can we sum it all up now? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2019;32(3):384–91.

Allen C, Perkins R, Schwahn B. A retrospective review of anesthesia and perioperative care in children with medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Paediatr Anaesth. 2017;27(1):60–5.

Beck CE, Witt L, Albrecht L, Dennhardt N, Böthig D, Sümpelmann R. Ultrasound assessment of gastric emptying time after a standardised light breakfast in healthy children: A prospective observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2018;35(12):937–41.

Du T, Hill L, Ding L, Towbin AJ, DeJonckheere M, Bennett P, et al. Gastric emptying for liquids of different compositions in children. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119(5):948–55.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Ethics Approval

University of Kentucky.

Consent to Participate

Completion of survey implied consent.

Consent for Publication

Notified in survey.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Pediatric Anesthesia

Appendices

Appendix

WELI NPO Survey

-

1.

I understand and fully accept the terms in the attached cover letter

-

2.

I agree to participate in this survey in which information from my responses will be collected and potentially used in future publication

-

3.

Do you currently allow children to drink clear liquids up to 1 h prior to the induction of anesthesia?

-

4.

If you responded no, what factors prohibit you/your group from making the change?

-

Medico-legal concerns?

-

Lack of support of American anesthesia societies?

-

Safety?

-

Other

-

-

5.

If you had medico-legal concerns, have you spoken to your risk department? What concerns did they have regarding changing your practice?

-

6.

If you responded no, does the lack of support by societies such as ASA or SPA influence your decision? If either of those organizations offered support, would you change your practice?

-

7.

Do you have any concerns regarding the safety of reducing clear liquid fasting guidelines?

-

8.

Would institutional reluctance to invest in changing patient communication (time/money) pose a barrier to implementing practice change?

WELI NPO Survey Results

34 Respondents/51 Total Surveyed

-

1.

I understand and fully accept the terms in the attached cover letter: 100%

-

2.

I agree to participate in this survey in which information from my responses will be collected and potentially used in future publication: 100%

-

3.

Do you currently allow children to drink clear liquids up to 1 h prior to the induction of anesthesia? 5 (14.7%) YES; 29 (85.3%) NO

-

4.

If you responded YES, can you comment on barriers you faced and how you were able to achieve the change at your respective institution?

-

a.

I allow for clear liquids 1 h before anesthesia, and so do about 2/3 of my partners. Our official instructions to parents/patients are 2 h NPO. Our group has reviewed the literature and discussed changing our institutional guidelines. Some more conservative members of the group are concerned about going against the published ASA guidelines for NPO and the fact that SPA does not have a guideline stating 1 h for clears. They have said that they will not try to stop us if we go ahead at 1 h with our own patients, but that they will not personally go until 2 h with their patients. The differences in limits among our group does not cause much problem, and we expect that we will change to 1-h NPO in the not too distant future

-

b.

Leadership buy-in 2. Legal/risk support 3. Change to surgical patient communications

-

c.

As the chair, I have left it to the independent practice of my team depending on clinical circumstances. Our policy states 2 h for clears, however can be moved to 1 h pending on anesthesiologist approval

-

d.

Our institutional policy is still 2 h—in line with ASA's general policy. I personally do not delay anesthesia if children present in the > 60 min but < 120 min time frame after consuming clears. Some of my colleagues also use a 1 h cut-off but it rarely comes up as the institution still uses 2 h as cut-off in the instructions. The obvious barrier is that it creates inconsistency within our team, so I emphasize to surgeons and families that this is outside our normal institutional policy, but in line with international recs etc.

-

e.

We had full support from our leadership which helped to remove many barriers. We made this change in conjunction with a QI project to decrease the overall fasting times for clear fluids. We had an average of about 9 h prior to our project and we were all in agreement that this was way too long. We also had the European data showing no increased adverse events with 1 h or even zero hour fasting times for clears. I am also currently working on a task force out of the ESA-IC to revise all fasting guidelines in children, which I hope might help break down barriers.

-

a.

-

5.

If you responded NO, what factor(s) inhibit you/your group from making the change? (please check all that apply)

-

a.

Medico-legal 23 (71.9%)

-

b.

Lack of support from ASA/SPA 26 (81.3%)

-

c.

Safety 7 (21.9%)

-

d.

Reluctance or concerns from surgeons/proceduralists 4 (12.5%)

-

e.

Resistance from hospital/administration/nursing to implementing changes 10 (31.3%)

-

f.

Other

-

a.

-

6.

For those who selected Other in the previous question or wish to add further commentary, please respond below

-

a.

Establishing consistency between providers to avoid confusion

-

b.

Concerns by anesthesia providers and reluctance to change

-

c.

Unaware that this was a new standard

-

d.

Concerns that different guidelines for pediatric versus adult patients will lead to confusion among both staff giving instructions and families receiving instructions. (We have a small integrated children's hospital within the adult hospital, so many periop staff cover both adult and pediatric patients)

-

e.

On an individualized delay a case for a 1 h clear liquid but we do not have this written in any policies.

-

f.

Our group is divided on the 1 h vs 2 h and we would like to have a unanimous decision before moving forward in the updating of our NPO guidelines.

-

g.

Only change my practice if my institution's policy changed to accept it

-

a.

-

7.

If either American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) or Society for Pediatric Anesthesiologists (SPA) supported a change to 1 h for clear liquid fasting times in pediatric patients, would you change your practice? YES (96.9%); NO (3.1%)

-

8.

Would institutional reluctance to invest in changing patient communication (time/money) pose a barrier to implementing practice change? YES (37.5%); NO (62.5%)

Table 3 Evidence for shortened clears fasting in children

Evidence for shortened clears fasting in children | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Reference (Country) | Study Design | Fasting Guideline | # Anesthetics (n) | Aspiration incidence (%) with notes |

Pfaff 2020 (USA) [33••] | Retrospective Multicenter Database study | 6–4-2, no subgroup analysis of < 2 h fasting times | 2,440,810 | 135 (0.006%) *, 11% of these involved NPO violation |

Beck 2020 (Germany) [37••] | Prospective Multicenter observational | Clears fasting of 1 h did not affect the incidence of adverse events | 12,093 | 4 confirmed (0.03%) 10 suspected (0.08%) 31 (0.26%) regurgitation |

Habre 2017 (Pan-European [8] | Prospective Multicenter | 6–4-2, no subgroup analysis of < 2 h fasting times | 31,131 | 29 (0.1%) |

Beach 2016 (USA) [11••] | Retrospective database analysis | 6–4-2 | 139,142 | 10 (0.007%), 0.01% in children appropriately NPO and 0.008% in those who were not NPO Status is not an independent predictor of aspiration or related major complications |

Tan and Lee 2016 (Singapore) [4] | Retrospective cohort | 6–4-2 | 102,425 | 22 (0.02%) |

Andersson 2018 (Sweden) [39••] | Prospective | 6–4-2 vs 6–4-0 | 2-h clears (n = 66) 0-h clears (n = 64) | None, median actual clears fasting time of 4 h for 6–4-2 group and 1 h for 6–4-0 group |

*Of the 135 cases, 51 (38%) resulted in patient harm, including 2 deaths (1.5%)

Table 4 Categorical Summary

Categorical Summary | |

|---|---|

Major Society Guidelines recommending One Hour Clear Liquid Fasting | o Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland [27] o European Society for Paediatric Anaesthesiology [27] o L’Association Des Anesthésistes-Réanimateurs Pédiatriques d’Expression Française [27] o The European Society of Anaesthesiology [56] o Canadian Pediatric Anesthesia Society [16] o The Society for Paediatric Anaesthesia of New Zealand and Australia [17] |

Concerns with Current Fasting Time Recommendations | o Fasting times typically far exceed recommended 2 h clears fasting [10, 35, 38, 72] o Low post-induction blood pressures with current 6–4-2 guidelines [42•] o Increased metabolic stress and insulin resistance [12, 36, 73] o Increased thirst, irritability [73], and emergence delirium [65] o Places children with undiagnosed metabolic conditions at risk (e.g. medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency patients) [74] |

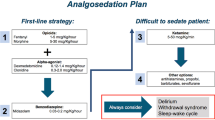

POCUS Evidence | o Gastric emptying time of clear fluids, as assessed by POCUS, was < 1 h in children age 4-17y/o [75] o Gastric emptying time, as assessed by POCUS, is < 4 h after a light breakfast [75] and for all liquids [76] o Allowing clear carbohydrate drink until premedication is associated with decreased actual fasting times and no change in gastric pH. Increased gastric volume is seen more often in patients with 30 min or shorter fasting times. [19••] |

Survey of Institutional Practice | o # US Hospitals surveyed: 51 o % Rate of response: 65.4% o Institutions with < 1 h clear liquid fasting requirement: 5/34 o Barriers to shortening clear liquid fasting requirement: Medicolegal, lack of support from national specialty societies, resistance from hospital/administration/nursing |

Recommendations | o Use of clinical judgment in patients with increased risk factors for aspiration: Gastrointestinal comorbid conditions, emergency surgery, higher ASA status (3-4), anticipated blood or secretions in airway following or during procedure, age 1–3 y/o [33••, 50] o Consider limiting volume of clears between 1–2 h to 3-5 ml/kg [27, 37••] o Use of risk stratification methods in guiding NPO recommendations for sedation procedures [30] o Institutional QI processes/interventions to address issues with adherence to NPO regulation (whether fasting less than or more than advised times). QI considerations include: interpreter services, separate written instructions for solids and liquids, [72] use of visual aids in instructions to ensure patients understand aspiration concerns, [46] institutional efforts to decrease procedural delays, and operating room schedule optimization |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lobaugh, L., Ojo, B., Pearce, B. et al. Revisiting Pediatric NPO Guidelines: a 5-Year Update and Practice Considerations. Curr Anesthesiol Rep 11, 490–500 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40140-021-00482-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40140-021-00482-1