Abstract

Introduction

This study aimed to investigate the long-term prognostic effects of different alteplase doses on patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS).

Methods

In this cohort study, we enrolled 501 patients with AIS treated with intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase, with the primary endpoint event of recurrence of ischemic stroke and the secondary endpoint event of death. The effects of different doses of alteplase on recurrence of ischemic stroke and death were analyzed using a Cox proportional risk model.

Results

Among 501 patients with AIS treated with thrombolysis, 295 patients (58.9%) and 206 patients (41.1%) were treated with low-dose and standard-dose alteplase, respectively. During the study period, 61 patients (12.2%) had a confirmed recurrence of ischemic stroke. Multivariate Cox proportional risk analysis showed that standard-dose alteplase thrombolysis (HR 0.511, 95% CI 0.288–0.905, P = 0.021) was significantly associated with a reduced risk of long-term recurrence of AIS, whereas atrial fibrillation was associated with an increased risk of long-term recurrence of AIS. Thirty-nine (7.8%) patients died during the study period. Multivariate Cox proportional risk analysis showed that age, baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score, and symptomatic steno-occlusion were associated with an increased long-term risk of death from AIS. The alteplase dose was not associated with the risk of death from AIS.

Conclusions

Standard-dose alteplase treatment reduced the risk of long-term recurrence of AIS after hospital discharge and the alteplase dose was not associated with the long-term risk of death from AIS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase is currently the most effective intravenous treatment for acute ischemic stroke (AIS). However, the effects of different alteplase doses on long-term prognosis in patients with AIS remains unknown. |

Most guidelines recommend an intravenous standard-dose alteplase within 3 or 4.5 h of symptom onset for eligible patients with AIS; different intravenous doses of alteplase thrombolysis may also be associated with long-term recurrence and death in patients with AIS. |

Standard-dose alteplase treatment reduced the risk of long-term recurrence of AIS after hospital discharge and the alteplase dose was not associated with the long-term risk of death from AIS. |

Introduction

Intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase is currently the most effective intravenous treatment for AIS. Intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase within 4.5 h of onset significantly improves the prognosis of patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) [1,2,3,4]. Currently, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS), most guidelines recommend an intravenous dose of alteplase (0.9 mg/kg) within 3 or 4.5 h of symptom onset for eligible patients with AIS [1, 2]. As a result of differences in the pathogenesis of AIS, the coagulation and fibrinolytic characteristics of Asian populations, and the relative lack of treatment costs in developing countries, several studies of intravenous thrombolysis with different doses of alteplase have been conducted in East Asian countries and regions [5,6,7,8,9,10]. The results of the Japan Alteplase Clinical Trial (J-ACT) study in Japan suggest that intravenous thrombolytic therapy with low-dose (0.6 mg/kg) alteplase may be safe and effective in Japanese patients with AIS [5], but the J-ACT study did not include a comparison with placebo or standard-dose alteplase. A study of standard-dose versus low-dose alteplase thrombolysis in Singapore found that patients receiving standard-dose alteplase thrombolysis had a significantly better short-term clinical prognosis and a lower risk of cerebral hemorrhage than those in the low-dose alteplase group [7].

However, most studies on intravenous thrombolysis in AIS have focused on the short-term prognosis [8, 11,12,13,14]. There are few relevant long-term studies and some of these compare patients receiving thrombolytic therapy with those receiving conventional therapy only [15,16,17]. Therefore, long-term studies on standard-dose versus low-dose alteplase for intravenous thrombolytic therapy in patients with AIS are lacking. The precise mechanism(s) by which thrombolysis improves long-term prognosis is(are) unknown. There is evidence that thrombolytic therapy can reduce infarct size and reduce the risk of readmission for pneumonia [18, 19]. Previous studies have shown that good functional outcomes in the short term are associated with improved long-term recurrence and survival, in part owing to reduced complications and increased independence [20, 21]. It is also known that different doses of alteplase can have different results, as defined by the 90-day modified Rankin Scale (mRS), and stroke severity is a strong predictor of prognosis for patients with stroke. Therefore, we assumed that the effect of different doses of alteplase on short-term prognosis and improved functional prognosis may reduce patient complications, which may further affect long-term recurrence and death. We conducted a prospective cohort study to investigate the risk factors associated with long-term recurrence and death in patients receiving different doses of intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase, with ischemic stroke recurrence and death as the endpoint events.

Methods

Study Population

The study population included all patients admitted for AIS and treated with intravenous thrombolysis from March 2017 to September 2021. Patients were divided into a low-dose group (0.6 mg/kg) and a standard-dose group (0.9 mg/kg) according to the dose of alteplase administered to patients in the stroke registry system. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age > 18 years; (2) clinical diagnosis of AIS within 4.5 h of onset; (3) cerebral hemorrhage and other nonischemic stroke diseases excluded by cranial CT or MRI; and (4) no contraindication to thrombolytic therapy. Patients were excluded if they presented with (1) death during hospitalization; (2) large cerebral infarction requiring craniotomy; or (3) incomplete imaging data. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute ischemic stroke in China have recommended the intravenous administration of 0.9 mg/kg alteplase for AIS as the standard dose in clinical practice. In addition, guidelines have also recommended that low-dose intravenously administered alteplase (0.6 mg/kg) may be associated with lower symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage risk on the basis of the results in the ENCHANTED [8, 11]. In clinical practice, standard or low doses are used on the basis of the treating physician’s initial assessment of the patient and professional judgment. This study included patients of Asian ethnicity. The ENCHANTED trial on low-dose alteplase was also performed in mostly Asian patients. Therefore, the findings of the present study are not necessarily transferable to Western populations.

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Fuyang People’s Hospital of Anhui Medical University (approval no. [2019] 67). The study procedures were in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. All patients or their relatives signed an informed consent form prior to inclusion. We used the Chinese version of the Rankin scale, and the research paper did not involve any commercial interests.

Clinical Data Collection

We collected demographic information, including age and sex, and medical history (including hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and current smoking or drinking). The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was used to assess the severity of ischemic stroke at admission. The mRS was used to assess the functional prognosis at discharge after AIS [22]. An mRS score ≥ 3 was defined as a poor prognosis. Discharge medications, including antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants, statins, antihypertensives, and glucose-lowering agents, were also recorded in detail. All patients underwent diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRA) or computed tomography angiography (CTA) within 48 h of admission. The type of lesion and the presence of arterial stenosis were recorded. Symptomatic steno-occlusion was characterized by greater than 50% stenosis or occlusion of the artery on MRA or CTA angiography associated with an acute ischemic lesion. All imaging data were interpreted by experienced neurologists and neuroradiologists who were unaware of the clinical factors of the patient.

Subtypes of Ischemic Stroke

The subtype classification of stroke was based on the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) [23]. Subtypes of stroke were categorized by large artery disease (LAD), small artery disease (SAD), cardiac embolism (CE), or other determined and undetermined etiologies. LAD was defined as patients with extracranial carotid stenosis or intracranial large artery stenosis greater than 50% with a stroke in the territory of the stenosed artery. Clinical manifestations included cortical damage (e.g., aphasia, neglect, apraxia, anopia, motor and/or sensory involvement) or brainstem or cerebellar dysfunction. The infarct areas were greater than 1.5 cm in diameter on MRI. CE was primarily characterized by nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, left ventricular motion segments, intracardiac thrombus or tumors, mitral stenosis, and other uncommon sources. SAD was defined as an infarct less than 15 mm in diameter localized in the deep regions of the brain or in the brain stem without LAD and CE. Patients with SAD had a typical clinical lacunar syndrome and did not have evidence of cerebral cortical dysfunction. Other determined etiology was characterized as patients with rare causes of stroke, including nonatherosclerotic vascular lesions, hypercoagulable states, or hematological disorders. Undetermined etiology was defined when no etiology could be identified despite extensive evaluation.

Follow-up Data

The primary endpoint events were ischemic stroke recurrence and all-cause death after hospital discharge. Enrolled patients with AIS were followed up every 6 months with a telephone interview or outpatient visit. Patients or their relatives were asked every year whether they had new symptoms. When patients had stroke symptoms, they were hospitalized and underwent a complete DWI-MRI examination to determine whether AIS had recurred. All recurrent events were based on clear documentation in medical records, and neurologic deficits had lasted longer than 24 h with confirmation of lesions by neuroimaging methods. The endpoint date of follow-up was March 31, 2022. All recurrent events were based on clear medical records, with symptoms of neurological deficits and lesions confirmed by neuroimaging methods. If a patient died during follow-up, the exact time and cause of death were recorded in detail. The follow-up interval was defined as the time between the stroke onset and recurrence, loss to follow-up, or death.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed with SPSS version 22.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR), and comparisons between groups were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Categorical variables are reported as absolute numbers and percentages (%). Differences in categorical variable distributions between groups were assessed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. The time to the first recurrence and death after intravenous thrombolysis in patients with AIS was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method using a two-sided log-rank test. The correlation between ischemic stroke recurrence and death and underlying factors was assessed by the Cox proportional hazard model. First, an unadjusted analysis was performed, and hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were subsequently calculated. Subsequently, a multivariate Cox proportional risk analysis was performed and adjusted for covariates that were significantly associated with ischemic stroke recurrence and death in the univariate analysis. HRs and 95% CIs were subsequently calculated. All tests used a two-sided P value of 0.05 as the threshold for statistical significance. The figures were generated using PowerPoint and GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0).

Results

Clinical Data

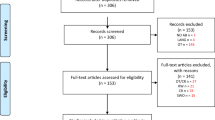

A total of 692 patients with AIS were admitted to receive intravenous thrombolytic therapy during the study period. A total of 501 eligible patients were eventually enrolled in our study (Fig. 1). Among them, there were 317 men (63.3%) and 184 women (36.7%). The mean age was 65.3 ± 12.8 years. Regarding thrombolytic therapy, 295 patients (58.9%) were treated with low-dose alteplase, and 206 patients (41.1%) were treated with standard-dose alteplase. The baseline characteristics of the study population according to thrombolytic dose are shown in Table 1. Compared with the low-dose alteplase thrombolysis group, the standard-dose alteplase thrombolysis group was younger and had a higher percentage of smokers. Figure 2 shows the distribution of mRS scores after hospital discharge grouped by thrombolytic dose.

The median follow-up time for recurrent events was 22.9 months (IQR 22.5; range 0.39–60.3 months), with a total of 61 (12.2%) patients experiencing recurrence during the study period, including 45 (15.3%) in the low-dose group and 16 (7.8%) in the standard-dose group. The median follow-up time for deaths was 26.0 months (IQR 21.3; range 0.8–60.3 months), with 39 (7.8%) patients dying during the study period, including 26 (8.8%) in the low-dose group and 13 (6.3%) in the standard-dose group.

Analysis of Risk of Recurrence of Intravenous Thrombolysis in Patients with AIS

Kaplan–Meier curve analysis showed that patients with standard-dose alteplase had a significantly lower risk of long-term recurrence than patients treated with low-dose alteplase (corrected P = 0.032, log rank test) (Fig. 3). Univariate Cox proportional risk analysis showed that standard-dose alteplase thrombolysis was associated with a reduced risk of long-term recurrence of AIS (HR 0.541, 95% CI 0.306–0.958, P = 0.035), using low-dose alteplase intravenous thrombolytic therapy as a reference, and that long-term recurrence risk reduction factors for intravenous thrombolytic therapy in AIS also included anticoagulants (HR 0.365, P = 0.004). The risk of long-term recurrence of AIS with intravenous thrombolysis was increased in patients with advanced age (HR 1.024, P = 0.023), ischemic heart disease (HR 2.058, P = 0.012), atrial fibrillation (HR 3.094, P < 0.001), symptomatic stenosis or occlusion (HR 1.908, P = 0.013), baseline NIHSS scores (HR 1.040, P = 0.046), and cardiac embolism (HR 3.512, P = 0.001). Multivariate Cox proportional risk analysis showed that standard-dose alteplase thrombolysis (HR 0.511, 95% CI 0.288–0.905, P = 0.021) was significantly associated with a reduced risk of long-term recurrence of AIS, whereas atrial fibrillation was associated with an increased risk of long-term recurrence of AIS (Table 2).

Analysis of Risk of Death by Intravenous Thrombolysis in Patients with AIS

Kaplan–Meier curve analysis showed that patients with standard-dose alteplase had no significantly different long-term death than patients treated with low-dose alteplase (corrected P = 0.607, log rank test) (Fig. 4). Univariate Cox proportional risk analysis showed that the long-term risk of death from AIS in patients with intravenous thrombolysis was increased in patients with advanced age (HR 1.076, P < 0.001), ischemic heart disease (HR 2.014, P = 0.049), atrial fibrillation (HR 3.961, P < 0.001), symptomatic stenosis or occlusion (HR 2.582, P = 0.005), baseline NIHSS scores (HR 1.134, P < 0.001), mRS (HR 1.559, P < 0.001), and cardiac embolism (HR 3.416, P = 0.013). Standard-dose alteplase thrombolysis was not associated with long-term risk of death from AIS (HR 0.840, 95% CI 0.431–1.636, P = 0.607). Multivariate Cox proportional risk analysis showed that age (HR 1.063, 95% CI 1.031–1.097, P < 0.001), baseline NIHSS scores (HR 1.110, 95% CI 1.063–1.158, P < 0.001), and symptomatic steno-occlusion (HR 2.104, 95% CI 1.058–4.185, P = 0.034) were associated with an increased risk of long-term death from AIS (Table 3).

Discussion

The results from this prospective cohort study showed that in patients with AIS, thrombolytic therapy with intravenously administered standard-dose alteplase can reduce the risk of long-term recurrence, atrial fibrillation is associated with an increased risk of long-term recurrence, and advanced age, symptomatic steno-occlusion, and baseline NIHSS scores can increase the long-term risk of death.

Alteplase is known to improve the clinical outcome of patients with AIS. Currently, the use of standard-dose intravenously administered alteplase as a thrombolytic therapy is recommended in the European, American, and Chinese guidelines, and the safety and efficacy of standard-dose intravenously administered alteplase have also been verified in Asian populations. In the Enhanced Control of Hypertension and Thrombolysis Stroke Study (ENCHANTED) [12], 63% of the enrolled patients were Asians, and 3310 patients eligible for thrombolytic therapy were treated with low-dose or standard-dose alteplase to study the effects of these therapies on 90-day mortality or disability outcomes among patients with AIS. The results showed that although low-dose alteplase can reduce the patient mortality rate, it can increase the disability rate. The data of 919 patients with AIS in the Thrombolysis Implementation and Monitoring of AIS in China (TIMS, China) database who received thrombolysis within 4.5 h of onset were analyzed. The results suggested that the clinical functional outcome at 90 days in the standard-dose alteplase group was significantly better than that in the low-dose alteplase group and that there was no increase in the risk of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage [8]. For Asian patients with AIS, compared with low-dose alteplase, standard-dose alteplase is also associated with a good clinical prognosis.

Many clinical studies have examined the effect of thrombolytic therapy with different doses of alteplase on patients with AIS, but these studies mostly focused on the short-term prognosis. Few studies have investigated the long-term outcomes of patients who received thrombolytic therapy with alteplase. To date, only a few studies have compared the long-term outcome between alteplase and conventional standardized treatment and have studied the effect of the delay from symptom onset to thrombolysis on the long-term outcomes of ischemic stroke [14, 15, 24, 25]. A long-term cohort study of 6252 patients with AIS who were treated with thrombolytic therapy showed that the delay from symptom onset to thrombolysis was associated with long-term recurrence and death, and the probability of these outcomes increased with increasing time from symptom onset to thrombolysis. Therefore, these studies cannot provide insights into the effect of the alteplase dose on long-term recurrence of and death from ischemic stroke. Thus, this study further examined the relationship between the selection of thrombolytic dose and the long-term recurrence of and death from ischemic stroke.

In this cohort study, compared with low-dose alteplase therapy, standard-dose alteplase therapy reduced the risk of ischemic stroke recurrence. Additionally, patients who received standard-dose alteplase therapy had lower mRS scores, and the proportion with a good clinical prognosis at discharge was higher than that for patients who received low-dose alteplase therapy (P < 0.05). Standard-dose alteplase is associated with improved functional outcomes, which may be the underlying mechanism for the long-term prognosis findings because patients with an improved functional prognosis may have fewer poststroke complications and a higher quality of life, ultimately leading to a lower risk of recurrence [19]. Previous studies have shown that early clinical prognosis improvements are associated with long-term recurrence and survival, partly owing to fewer complications and more independence in life [26, 27]. In addition, patients with a higher degree of disability may present more clinical complications, potentially affecting the implementation of appropriate treatments and interfering with physical activities, thus increasing the risk of cerebrovascular events. This cohort study found that the standard-dose alteplase group had lower mRS scores at discharge than the other groups and that standard-dose intravenously administered alteplase as a thrombolytic therapy was associated with the risk of AIS recurrence. These results suggest that functional status and the risk of recurrence are associated, indicating that standard-dose thrombolytic therapy can improve the functional prognosis of patients and reduce the long-term risk of recurrence.

This study also found no significant difference in the long-term risk of death between patients who received standard-dose and low-dose alteplase therapies. However, the HR for standard-dose alteplase was 0.840, and the risk of death was lower than that for the low-dose alteplase group, which may be related to the better prognosis and good functional recovery of patients receiving standard-dose alteplase.

In this study, among several comorbidities (such as atrial fibrillation and symptomatic steno-occlusion), atrial fibrillation was still associated with the risk of recurrence and death even after adjusting for age and several other comorbidities. A previous study found that 46% of patients with stroke and atrial fibrillation did not receive anticoagulation treatment [28]. Additionally, a recent study found that 33% of patients with stroke who were previously diagnosed with atrial fibrillation did not receive anticoagulant drugs or antiplatelet drugs at discharge [29]. In this study, atrial fibrillation in the low-dose group was 18% but anticoagulation at discharge was only 6.4%; the corresponding figures in the standard-dose group were 16% vs 9.2%. Although patients were repeatedly informed of the importance and relative safety of anticoagulant use in patients with atrial fibrillation at discharge, differences in patient literacy, different economic status, and some concern about the risk of bleeding after medication administration led to different medication adherence and differences in anticoagulant use between the two groups. In addition, 55.9% of patients with atrial fibrillation did not receive regular anticoagulation therapy, which is a particular concern because this study found that atrial fibrillation significantly increased the risk of long-term recurrence from AIS, and these findings have been verified in other studies [29, 30]. In addition, advanced age, symptomatic steno-occlusion, and baseline NIHSS scores can increase the long-term risk of death from AIS [31,32,33]. Therefore, it is important to identify patients with AIS and a particularly high risk of a poor long-term prognosis after intravenous thrombolysis and to develop future secondary prevention strategies.

In this cohort study, we investigated, for the first time, the relationship between the thrombolytic dose and long-term recurrence and death after hospital discharge in patients with AIS. This study examined standard-dose and low-dose alteplase therapies for patients with AIS, and ischemic stroke recurrence and death were used as the endpoints, providing strong support for the analysis of the relationship between different alteplase doses and the risk of long-term recurrence of and death from AIS. In addition, this study has a longer follow-up period than previous studies.

Although our research incorporates several novel discoveries, we acknowledge that our study has some limitations. First, this was an observational rather than an experimental study, and clinicians may have selection bias in dose selection. Despite multivariate adjustment for several potential confounders, the possibility of residual confounding cannot be excluded. Second, some patients with recurrent ischemic stroke may not go to the hospital because of mild or complete a lack of symptoms, which may result in underestimation of the risk of recurrent ischemic stroke. Third, we excluded patients with large cerebral infarction requiring craniectomy; this reduces the impact of confounding factors and makes the cohort study more pure, but may have an impact on patient prognosis assessment. Fourth, this study focused on stroke events. Carotid artery disease and heart failure are not used as routine indicators of stroke recurrence and death, so these two variables were not included, but we will include these variables in future studies.

Conclusion

This study found that standard-dose intravenously administered alteplase as a thrombolytic therapy can reduce the risk of the long-term recurrence of AIS after discharge, atrial fibrillation is associated with higher risks of long-term recurrence from AIS after discharge, and advanced age, symptomatic steno-occlusion, and baseline NIHSS scores are associated with a long-term risk of death. These findings support the long-term benefits of using standard-dose intravenously administered alteplase as a thrombolytic therapy in accordance with currently accepted guidelines and reinforce the importance of enhancing secondary prevention in patients after discharge.

References

Demaerschalk BM, Kleindorfer DO, Adeoye OM, et al. Scientific rationale for the inclusion and exclusion criteria for intravenous alteplase in acute ischemic stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2016;47(2):581–641.

Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, et al. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study Investigators. Lancet. 1998;352(9136):1245–51.

Tsivgoulis G, Katsanos AH, Kadlecová P, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis for ischemic stroke in the golden hour: propensity-matched analysis from the SITS-EAST registry. J Neurol. 2017;264(5):912–20.

Zheng H, Yang Y, Chen H, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3–4.5 hours after acute ischaemic stroke: the first multicentre, phase III trial in China. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2020;5(3):285–90.

Yamaguchi T, Mori E, Minematsu K, et al. Alteplase at 0.6 mg/kg for acute ischemic stroke within 3 hours of onset: Japan Alteplase Clinical Trial (J-ACT). Stroke. 2006;37(7): 1810–15.

Bandettini di Poggio M, Finocchi C, Brizzo F, et al. Management of acute ischemic stroke, thrombolysis rate, and predictors of clinical outcome. Neurol Sci. 2019;40(2):319–26.

Sharma VK, Tsivgoulis G, Tan JH, et al. Feasibility and safety of intravenous thrombolysis in multiethnic Asian stroke patients in Singapore. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;19(6):424–30.

Liao X, Wang Y, Pan Y, et al. Standard-dose intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator for stroke is better than low doses. Stroke. 2014;45(8):2354–8.

Kim JS, Kim YJ, Lee KB, et al. Low-versus standard-dose Intravenous alteplase in the context of bridging therapy for acute ischemic stroke: a Korean ENCHANTED Study. J Stroke. 2018;20(1):131–9.

Chen CH, Tang SC, Chen YW, et al. Effectiveness of standard-dose vs. low-dose alteplase for acute ischemic stroke within 3–4.5 h. Front Neurol. 2022;13:763963.

Wang X, Robinson TG, Lee TH, et al. Low-dose vs standard-dose alteplase for patients with acute ischemic stroke: secondary analysis of the ENCHANTED randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(11):1328–35.

Anderson CS, Robinson T, Lindley RI, et al. Low-dose versus standard-dose intravenous alteplase in acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(24):2313–23.

Zhou Z, Delcourt C, Xia C, et al. Low-dose vs standard-dose alteplase in acute lacunar ischemic stroke: the ENCHANTED trial. Neurology. 2021;96(11):e1512–26.

Chao AC, Han K, Lin SF, et al. Low-dose versus standard-dose intravenous alteplase for octogenerian acute ischemic stroke patients: a multicenter prospective cohort study. J Neurol Sci. 2019;399:76–81.

Muruet W, Rudd A, Wolfe CDA, Douiri A. Long-term survival after intravenous thrombolysis for ischemic stroke: a propensity score-matched cohort with up to 10-year follow-up. Stroke. 2018;49(3):607–13.

Yu AYX, Fang J, Kapral MK. One-year home-time and mortality after thrombolysis compared with nontreated patients in a propensity-matched analysis. Stroke. 2019;50(12):3488–93.

Gensicke H, Seiffge DJ, Polasek AE, et al. Long-term outcome in stroke patients treated with IV thrombolysis. Neurology. 2013;80(10):919–25.

Simpkins AN, Dias C, Norato G, Kim E, Leigh R, NIH Natural History of Stroke Investigators. Early change in stroke size performs best in predicting response to therapy. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;44(3–4):141–9.

Terkelsen T, Schmitz ML, Simonsen CZ, et al. Thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke is associated with lower long-term hospital bed day use: a nationwide propensity score-matched follow-up study. Int J Stroke. 2016;11(8):910–6.

Schmitz ML, Simonsen CZ, Hundborg H, et al. Acute ischemic stroke and long-term outcome after thrombolysis: nationwide propensity score-matched follow-up study. Stroke. 2014;45(10):3070–2.

Magalhães R, Abreu P, Correia M, Whiteley W, Silva MC, Sandercock P. Functional status three months after the first ischemic stroke is associated with long-term outcome: data from a community-based cohort. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;38(1):46–54.

Maier IL, Bauerle M, Kermer P, Helms HJ, Buettner T. Risk prediction of very early recurrence, death and progression after acute ischaemic stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2013;20(4):599–604.

Chen PH, Gao S, Wang YJ, Xu AD, Li YS, Wang D. Classifying ischemic stroke, from TOAST to CISS. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18(6):452–6.

Yafasova A, Fosbøl EL, Johnsen SP, et al. Time to thrombolysis and long-term outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke: a nationwide study. Stroke. 2021;52(5):1724–32.

Man S, Xian Y, Holmes DN, et al. Association between thrombolytic door-to-needle time and 1-year mortality and readmission in patients with acute ischemic stroke. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2170–84.

Slot KB, Berge E, Dorman P, et al. Impact of functional status at six months on long term survival in patients with ischaemic stroke: prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2008;336(7640):376–9.

Kim MS, Joo MC, Sohn MK, et al. Impact of functional status on noncardioembolic ischemic stroke recurrence within 1 year: the Korean stroke cohort for functioning and rehabilitation study. J Clin Neurol. 2019;15(1):54–61.

McKevitt C, Coshall C, Tilling K, Wolfe C. Are there inequalities in the provision of stroke care? Analysis of an inner-city stroke register. Stroke. 2005;36(2):315–20.

Flach C, Muruet W, Wolfe CDA, Bhalla A, Douiri A. Risk and secondary prevention of stroke recurrence: a population-base cohort study. Stroke. 2020;51(8):2435–44.

Seet RC, Zhang Y, Wijdicks EF, Rabinstein AA. Relationship between chronic atrial fibrillation and worse outcomes in stroke patients after intravenous thrombolysis. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(11):1454–8.

Huang WY, Weng WC, Su FC, Lin SW. Association between stroke severity and 5-year mortality in ischemic stroke patients with high-grade stenosis of internal carotid artery. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27(11):3365–72.

Andersen KK, Andersen ZJ, Olsen TS. Predictors of early and late case-fatality in a nationwide Danish study of 26,818 patients with first-ever ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2011;42(10):2806–12.

Bryndziar T, Matyskova D, Sedova P, et al. Predictors of short- and long-term mortality in ischemic stroke: a community-based study in Brno, Czech Republic. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2022;51(3):296–303.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Fuyang Health and Health Commission Project (FY2019-056) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82071460). The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

We acknowledge the American Journal Experts (AJE) team for their help in language editing.

Author Contributions

Mingfeng Zhai and Shugang Cao were involved in the design of the study, data collection, interpretation of the data, and manuscript writing. Wanyin Liu, Yongzhan Fu and Qiyue Guan participated in the study design, data collection, and statistical analysis. Jinwei Yang, Xiaoyan Cao, and Zhong Dong participated in the data analysis, interpretation of the data, and manuscript revision. Yu Wang and Hongbo Liu were responsible for drafting the manuscript and revising it. All authors approved the protocol.

Disclosures

Mingfeng Zhai, Shugang Cao, Jinwei Yang, Xiaoyan Cao, Zhong Dong, Wanyin Liu, Yongzhan Fu, Qiyue Guan, Yu Wang, and Hongbo Liu declare that they have nothing to disclose regarding the content of this article.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was performed in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. Ethics approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Fuyang People’s Hospital of Anhui Medical University (approval no. [2019] 67). All subjects or their legally authorized representatives provided written informed consent.

Data Availability

All data generated for this study are included in the article. The data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhai, M., Cao, S., Yang, J. et al. Effect of Intravenous Thrombolytic Dose of Alteplase on Long-Term Prognosis in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke. Neurol Ther 12, 1105–1118 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-023-00488-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-023-00488-3