Abstract

This article offers an analysis of ecologist Charles Elton’s “functional” concept of the niche and of the notion of function implicitly associated with it. It does so in part by situating Elton’s niche concept within the broader context of the “functionalist-interactionist” approach to ecology he introduced, and in relation to his views on the relationship between ecology and evolution. This involves criticizing the common claim that Elton’s idea of species as fulfilling functional roles within ecological communities committed him to an idea of communities as units of selection. While such a claim implicitly attributes to Elton an understanding of function along the lines of the selected-effects theory of function advocated by many biologists and philosophers of biology, Elton’s use of the niche concept, I maintain, involves an understanding of function more along the lines of alternative nonselectionist theories such as the causal-role, goal-contribution, and organizational theories. I also briefly discuss how ecologists after Elton also tend to have typically adopted a nonselectionist understanding of the function concept, similar to his.

reproduced from Summerhayes and Elton 1923, p. 232)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As Elton himself reports, he and Grinnell “independently started using the term” (see Elton and Miller 1954, p. 477).

His focus on animals reflects only the fact that he developed the concept in the context of animal ecology.

Elton’s analogies between animal communities and human societies were presumably influenced in part by sociologist Alexander Carr-Saunders (1886–1966), who is known to have acted as Elton’s mentor at Oxford (together with zoologist Julian Huxley). Elton’s construal of ecology as “the sociology and economics of animals” is explicitly linked to Carr-Saunders’s (1922) study of the “sociology and economics” of humans in the preface of Animal Ecology (Elton 1927, p. vii). On the relationship between Elton and Carr-Saunders, see Sheail (1987, p. 90), Hagen (1992, pp. 56–57), and Anker (2001, Chap. 3). On functionalism in sociology in general, see Munch (1976), Moore (1978), and Bigelow (1998).

For the sake of comprehensiveness, it should be mentioned that Elton considered animal populations to be regulated not only through the intracommunity factors just described, but also through climatic factors (Elton 1927, pp. 119, 123), and through the migration of animals from more populated to less populated areas (Elton 1930, pp. 61–62; 1933, pp. 70–72).

Elton’s occasional description of some animals’ niches in relation to abiotic factors evokes the possibility of complementary ecological functions based on species’ impacts on abiotic factors (see Schoener 1989, p. 86; Griesemer 1992, p. 234; Leibold 1995, p. 1373). For instance, he described land crabs living in burrows on coral islands and earthworms elsewhere as occupying the same (soil-burrowing) niche (Elton 1927, p. 67). This suggests the possibility of ecological functions associated with what we would now call ecosystem engineering (Jones et al. 1994; Berke 2010). This idea, however, is not fully developed in Elton’s works.

Kimler bases this reading partly on personal communication with Elton (see Kimler 1986, p. 224).

Historian of ecology Peder Anker (2001, p. 112) notes that Wells et al.’s ecology chapter was entirely reviewed by Elton before publication.

In a later paper, Elton even drew attention to the phenomenon of cultural evolution, arguing that “among the higher animals we can perceive a method of evolution along a mental plane, unconnected with the spread of new mutations, a method which leads on a small scale to the production of customs, cultures, and gregarious habits, similar to those found in man” (Elton 1931, p. 134; quoted in Hagen 1992, pp. 60–61).

It is important to note that Elton’s rejection of this particular explanation for community stability did not amount to a wholesale rejection of the idea that communities achieved some kind of stability. Elton fully admitted that communities have “some power of regulation, of compensating here for a disturbance there,” and he remarked that, “the species composition of most communities remains very much the same over long periods” (Elton 1930, pp. 38, 25). His main point was that community stability is achieved through other factors, such as the migration of animals from more to less populated areas. This is partly why, above, I say that Elton rejected “a version of” the balance of nature idea. This is meant to leave open the possibility that his views may be ones that other ecologists would interpret as aligning with the balance-of-nature idea. For discussions of Elton’s ideas on community stability and the balance of nature, see Hagen (1992, pp. 56–60), Haak (2000, pp. 26–29), and Dussault (2020, sec. 4.3). For an analysis of the various views that ecologists have associated with the balance-of-nature idea, see Jansen (1972).

This implication may seem to be challenged by Roberta Millstein’s (forthcoming) recent defense of the possibility of selected-effects ecological functions based in coevolution rather than community or ecosystem-level selection. Millstein’s discussion is of particular relevance here, given its focus on Aldo Leopold and given Elton’s known influence on Leopold. Millstein’s discussion, however, seems implicitly focused on a different notion of function than the one I am focusing on here. As she recognizes (footnote 1), her discussion is focused on function as a type of activity achieved by organisms across communities (e.g., predation, parasitism). In contrast, I am here concerned with function as a type of contribution to the capacities or activities of a larger system (e.g., as highlighted above, the transfer of organic matter through the food cycle, the regulation of animal populations involved within the community). Notwithstanding Millstein’s arguments, a selected-effects interpretation of the latter functions would still seem to require community-level selection.

Other philosophers (e.g., Wright 1973, pp. 147–148; Boorse 1976, p. 76) make essentially the same contrast by distinguishing the notion of what the function of x is (Achinstein’s design functions) from the notion of what x functions as (Achinstein’s use and service functions). Wright, however, restricts the legitimate sense of function to the first notion, which, as regards biological functions (as opposed to technical functions), he analyzes in selected-effects terms.

As some historians of ecology have noted, 20th-century ecologists tended to use organicist and mechanistic analogies interchangeably (see Hagen 1992, pp. 11–14; Marshall 2002, Chap. 7). Elton, for his part, at times criticized the mechanistic analogy (see Elton 1930, p. 30) and, as far as I am aware of, never committed to the organicist analogy.

I leave it open whether, from a functionalist sociological perspective, humans can soundly be depicted as fulfilling social functions within their societies. See note 6 above for references on functionalism in sociology.

For a more detailed comparison of Elton’s ideas on ecological communities and those of ecologists who construed communities by close analogy with organisms, see Dussault (2020).

In more contemporary parlance we could say that ecological communities were, for Elton, functionally organized entities by virtue of being niche-construction networks—that is, networks of species that, by their simple presence or their effect on the environment, provide key conditions of existence to each other (see Odling-Smee et al. 2003; Barker and Odling-Smee 2014).

For an application of the organizational theory of function to the context of ecology, see Nunes-Neto et al. (2014).

For the sake of exactness, it should be mentioned that one of the nonselectionist theories mentioned above—namely the organizational theory—is intended to account as much for the teleological (the why) as for the systemic (the how) dimensions of the function concept (see, e.g., Mossio et al. 2009, sec. 4.1). Nevertheless, what has primary relevance for my purposes is how, by accounting for the systemic dimension, the organizational theory, like other nonselectionist theories, can shed light on Elton’s nonselectionist use of the function concept.

On Mayr’s contrast between why and how questions and its relationship to the use of the function concept in ecology in general, see Hagen (1992, pp. 150–151).

It should be noted, however, that, although Dice seems to have shared Elton’s nonselectionist understanding of function, he did not associate the niche concept itself with functions fulfilled by species within communities (see Dice 1952, p. 227). Like most ecologists, he followed Grinnell in adopting a niche concept focused on species’ ecological requirements (in his case, mainly the resources that species require) (for a discussion, see Hurlbert 1981).

See however Millstein (forthcoming) for a dissenting view.

References

Achinstein P (1977) Function statements. Philos Sci 44:341–367

Allee WC, Emerson AE, Park O, Park T, Schmidt KP (1949) Principles of animal ecology. Saunders, Philadelphia

Alley TR (1985) Organism-environment mutuality epistemics, and the concept of an ecological niche. Synthese 65:411–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00869278

Amundson R, Lauder GV (1994) Function without purpose. Biol Philos 9:443–469

Angner E (2009) Hayek and natural law. Routledge, Milton

Anker P (2001) Imperial ecology: environmental order in the British Empire, 1895–1945. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Barker G, Odling-Smee J (2014) Integrating ecology and evolution: niche construction and ecological engineering. In: Barker G, Desjardins E, Pearce T (eds) Entangled life: organism and environment in the biological and social sciences. Springer, New York, pp 187–211

Berke SK (2010) Functional groups of ecosystem engineers: a proposed classification with comments on current issues. Integr Comp Biol 50:147–157. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icq077

Bigelow JC (1998) Functionalism in social science. Routledge Encycl. Philos. Routledge, London, pp 813–819

Birkhead T, Wimpenny J, Montgomerie B (2014) Ten thousand birds: ornithology since darwin. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Boorse C (1976) Wright on functions. Philos Rev 85:70–86

Borrello ME (2010) Evolutionary restraints: the contentious history of group selection. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Carr-Saunders AM (1922) The population problem: a study in human evolution. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Chitty D (1996) Do lemmings commit suicide?: beautiful hypotheses and ugly facts. Oxford University Press, New York

Cooper GJ (2003) The science of the struggle for existence: on the foundations of ecology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge/New York

Cooper GJ, El-Hani CN, Nunes-Neto N (2016) Three approaches to the teleological and normative aspects of ecological functions. In: Eldredge N, Pievani T, Serrelli E, Tëmkin I (eds) Evolutionary theory: a hierarchical perspective. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 103–124

Cox DL (1979) Charles Elton and the emergence of modern ecology. Doctoral dissertation, Washington University

Craver CF (2001) Role functions, mechanisms, and hierarchy. Philos Sci 68:53–74. https://doi.org/10.1086/392866

Cummins RC (1975) Functional analysis. J Philos 72:741–764

Dice LR (1952) Natural communities. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

Dussault AC (2018) Functional ecology’s non-selectionist understanding of function. Stud Hist Philos Biol Biomed Sci 70:1–9

Dussault AC (2020) Neither superorganisms nor mere species aggregates: Charles Elton’s sociological analogies and his moderate holism about ecological communities. Hist Philos Life Sci 42:25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40656-020-00316-z

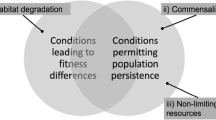

Dussault AC, Bouchard F (2017) A persistence enhancing propensity account of ecological function to explain ecosystem evolution. Synthese 194:1115–1145

Elton CS (1924) Periodic fluctuations in the numbers of animals: their causes and effects. J Exp Biol 2:119–163

Elton CS (1927) Animal ecology. Macmillan, New York

Elton CS (1929) Ecology, animal. In: Encyclopædia Britannica, 14th edn. Encyclopædia Britannica, London, pp 915–924

Elton CS (1930) Animal ecology and evolution. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Elton CS (1931) Theories of evolution. Sch Sci Rev 13(56–61):130–136

Elton CS (1933) The ecology of animals. Methuen, London

Elton CS (1950) A fundamental treatise on animal ecology. J Anim Ecol 19:74–78. https://doi.org/10.2307/1572

Elton CS (1954) An ecological text book. J Anim Ecol 23:382. https://doi.org/10.2307/1992

Elton CS (1958) The ecology of invasions by animals and plants. Methuen/Chapman & Hall, Kluwer Academic, Chicago

Elton CS (1963) Self-regulation of animal populations. Nature 197:634–634

Elton CS (1966) The pattern of animal communities. Chapman and Hall, London

Elton CS, Miller RS (1954) The ecological survey of animal communities: with a practical system of classifying habitats by structural characters. J Ecol 42:460–496. https://doi.org/10.2307/2256872

Garson J (2016) A critical overview of biological functions. Springer, Cham

Gay H (2013) Silwood circle: a history of ecology and the making of scientific careers in late twentieth-century Britain. Imperial College Press, London

Godfrey-Smith P (1993) Functions: consensus without unity. Pac Philos Q 74:196–208

Gould SJ, Lewontin RC (1979) The spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian paradigm: a critique of the adaptationist programme. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 205:581–598

Griesemer JR (1992) Niche: historical perspectives. In: Keller EF, Lloyd E (eds) Keywords in evolutionary biology. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, pp 231–240

Grinnell J (1917) The niche-relationships of the California thrasher. Auk 34:427–433

Grinnell J (1924) Geography and evolution. Ecology 5:225–229. https://doi.org/10.2307/1929447

Grinnell J (1928) Presence and absence of animals. Univ Calif Chron 30:429–450

Grinnell J, Storer TI (1924) Animal life in the Yosemite: an account of the mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians in a cross-section of the Sierra Nevada. University of California Press, Berkeley

Haak C (2000) The concept of equilibrium in population ecology. Doctoral dissertation, Dalhousie University

Hagen JB (1992) An entangled bank: the origins of ecosystem ecology. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick

Holt RD (2005) On the integration of community ecology and evolutionary biology: historical perspectives and current prospects. In: Cuddington K, Beisner BE (eds) Ecological paradigms lost: routes of theory change. Elsevier Academic Press, Amsterdam/Boston, pp 235–271

Hurlbert SH (1981) A gentle depilation of the niche: Dicean resource sets in resource hyperspace. Evol Theory 5:177–184

Hutchinson GE (1957) Concluding remarks. Cold Springs Harb Symp Quant Biol 22:415–427

Hutchinson GE (1978) An introduction to population ecology. Yale University Press, New Haven

Huxley J (1942) Evolution: the modern synthesis. George Allen & Unwin, London

Jansen AJ (1972) An analysis of “balance in nature” as an ecological concept. Acta Biotheor 21:86–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01556339

Jax K (2010) Ecosystem functioning. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Jones CG, Lawton JH, Shachak M (1994) Organisms as ecosystem engineers. Oikos 69:373–386

Kimler WC (1986) Advantage, adaptiveness, and evolutionary ecology. J Hist Biol 19:215–233

Kingsland SE (1985) Modeling nature: episodes in the history of population ecology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Leibold MA (1995) The niche concept revisited: mechanistic models and community context. Ecology 76:1371–1382. https://doi.org/10.2307/1938141

Looijen RC (2000) Holism and reductionism in biology and ecology: the mutual dependence of higher and lower level research programmes. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht

MacArthur R, Levins R (1967) The limiting similarity, convergence, and divergence of coexisting species. Am Nat 101:377–385

Maclaurin J, Sterelny K (2008) What is biodiversity? University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Marshall A (2002) The unity of nature wholeness and disintegration in ecology and science. Imperial College Press, London

Mayr E (1961) Cause and effect in biology. Science 134:1501–1506

McIntosh RP (1985) The background of ecology: concept and theory. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

McLaughlin P (2001) What functions explain: functional explanation and self-reproducing systems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Millikan RG (1989) In defense of proper functions. Philos Sci 56:288–302

Millikan RG (1984) Language, thought, and other biological categories. MIT Press, Cambridge

Millstein R (forthcoming) Functions and functioning in Aldo Leopold’s land ethic and in ecology. Philos Sci. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/710619

Moore WE (1978) Functionalism. In: Bottomore TB, Nisbet R (eds) A history of sociological analysis. Basic Books, New York, pp 321–417

Morris DW (2003) Toward an ecological synthesis: a case for habitat selection. Oecologia 136:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-003-1241-4

Mossio M, Saborido C, Moreno A (2009) An organizational account of biological functions. Br J Philos Sci 60:813–841

Munch PA (1976) The concept of “function” and functional analysis in sociology. Philos Soc Sci 6:193–213

Nagel E (1977) Teleology revisited. J Philos 74:261–301

Neander K (1991) Functions as selected effects: the conceptual analyst’s defense. Philos Sci 58:168–184

Nicholson AJ (1933) The balance of animal populations. J Anim Ecol 2:132–178

Nunes-Neto N, Moreno A, El-Hani CN (2014) Function in ecology: an organizational approach. Biol Philos 29:123–141

Odenbaugh J (2010) On the very idea of an ecosystem. In: Hazlett A (ed) New waves in metaphysics. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, pp 240–258

Odling-Smee FJ, Laland KN, Feldman MW (2003) Niche construction: the neglected process in evolution. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Odum EP (1953) Fundamentals of ecology. Saunders, Philadelphia

Odum EP (1959) Fundamentals of ecology. Saunders, Philadelphia

Pigliucci M, Müller GB (eds) (2010) Evolution, the extended synthesis. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass

Pocheville A (2015) The ecological niche: history and recent controversies. In: Heams T, Huneman P, Lecointre G, Silberstein M (eds) Handbook of evolutionary thinking in the sciences. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 547–586

Saborido C (2014) New directions in the philosophy of biology: a new taxonomy of functions. In: Galavotti MC, Dieks D, Gonzalez WJ, Hartmann S, Uebel T, Weber M (eds) New directions in the philosophy of science. Springer, New York, pp 235–251

Schlosser G (1998) Self-re-production and functionality. Synthese 116:303–354

Schoener TW (1989) The ecological niche. In: Cherrett JM, Bradshaw AD (eds) Ecological concepts: the contribution of ecology to an understanding of the natural world. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, pp 79–114

Scudo FM (1984) The “golden age” of theoretical ecology; a conceptual appraisal. Rev Eur Sci Soc 22:11–64

Sheail J (1987) Seventy-five years in ecology: the British Ecological Society. Blackwell, Oxford

Shelford VE (1913) Animal communities in temperate America as illustrated in the Chicago region. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Walsh DM (2008) Function. In: Stathis P, Curd M (eds) The Routledge companion to philosophy of science. Routledge, London/New York

Wells HG, Huxley J, Wells CP (1931) The science of life. Cassell and Company, London

West-Eberhard MJ (2003) Developmental plasticity and evolution. Oxford University Press, New York

Williams GC (1966) Adaptation and natural selection: a critique of some current evolutionary thought. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Wilson DS, Sober E (1989) Reviving the superorganism. J Theor Biol 136:337–356

Wouters A (2003) Four notions of biological function. Stud Hist Philos Sci Part C 34:633–668

Wouters A (2005) The function debate in philosophy. Acta Biotheor 53:123–151

Wright L (1973) Functions Philos Rev 82:139–168

Wynne-Edwards VC (1962) Animal dispersion in relation to social behavior. Oliver and Boyd, Edinburgh

Wynne-Edwards VC (1985) Backstage and upstage with ‘Animal Dispersion’. In: Dewsbury DA (ed) Leaders in the study of animal behavior: autobiographical perspectives. Bucknell University Press, Cranbury, New Jersey, pp 487–512

Acknowledgments

The author is thankful to the audience of the session “L’environnement dans la biologie du XXIe siècle: Ambiguïtés conceptuelles et défis épistémologiques,” held at the 2018 Société de philosophie des sciences conference in Nantes, France, where an earlier version of this paper was presented, as well as to Roberta Millstein and two anonymous referees, for helpful comments. He also thanks Xander Selene for editing the manuscript. The work for this paper was supported by a research grant from the Fonds de recherche du Québec—Société et culture (FRQSC, 2018-CH-211053).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dussault, A.C. Functionalism without Selectionism: Charles Elton's "Functional" Niche and the Concept of Ecological Function. Biol Theory 17, 52–67 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13752-020-00360-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13752-020-00360-9