Abstract

The aims of the paper are to identify and assess the determinants of transition to renewable and sustainable energy development in Azerbaijan and Poland. Both countries have a clear target to increase the share of renewable energy sources (RES) in the gross final energy consumption, i.e. Poland in the National Energy and Climate Plan for the years 2021–2030 declares that it wishes to achieve 21–23% by 2030 (total consumption in electricity, heating and cooling as well as for transport purposes). But there are currently significant producers and consumers of conventional energy carriers, respectively coal and oil, and these fuels ensure an appropriate level of energy security and production stability. Moreover, in Poland, the mining sector plays a very important social role, whereas the oil industry in Azerbaijan creates significant budget revenue. Therefore, even with stronger EU and worldwide climate policy and a decreasing cost of cleaner forms of energy, there are many challenges and obstacles for such countries in increasing energy from RES associated with energy security, efficiency, existing infrastructure, competitiveness and social aspects. In order to identify best practices for the transition to decarbonisation, the availability of energy resources, energy market structures, national strategies and policies were compared using PESTEL analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

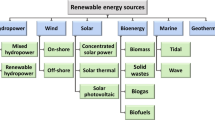

Increasing the share of renewable energy sources (RES) and carbon neutrality is an important policy aim of the EU and growing numbers of countries are adopting greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction targets and making ambitious investments in clean technologies. Such transition still requires innovation, policy and financial support to achieve massive technological advances and sharp cost reductions. Today, the primary energy source all over the world remains non-renewable fossil fuels that have been and will continue to be a major cause of pollution and climate change. With increasing energy demand and growing concerns for environmental impacts, RES are receiving increased attention for their inherent low pollutant and GHG emissions. However, the intermittent and uncontrollable nature of RES introduces new technical challenges for integration into electric power systems, especially as the market share of renewable energy is growing (Kordana et al. 2019).

In Azerbaijan, the State Programme on the Use of Alternative and Renewable Energy Sources was approved in 2004 to promote power generation from RES and to utilise hydrocarbon energy sources more efficiently. In the memorandum of understanding signed between the EU and Azerbaijan in 2006, the objectives included the modernisation of the electricity grid, enhancement of the security and reliability of the energy infrastructure; the preparation of programmes and regulations for the development of the RES sector; and the achievement of the efficient use of energy. In December 2011, a second long-term government strategy for the development of alternative and renewable energy sources for the years 2012–2020 was accepted which aims to reduce GHG emissions by 20% from 1990 levels, to scale up the rate of renewable energy by up to 20% by using electricity as well as increasing energy efficiency by 20% by 2020 (Caspian Information Centre 2013). Moreover, in 2012, the government of Azerbaijan accepted the development plan “Azerbaijan 2020: Look into the Future”, where they argue that the quantity of energy consumed, and CO2 released for the production of one unit of GDP must be analogous with matching OECD member country norms by 2020 (Aydin 2019). The Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR) shows that fossil CO2 emissions in Azerbaijan dropped significantly from 1990 from 58,077 Mt CO2 to 30,488 Mt CO2 in 2005 and reached 34,704 Mt in 2018 (Muntean et al. 2018). However, this has been achieved as a result of the decline in the total primary energy supply per capita in the country, i.e. especially from 3.17 toe/capita in 1990 to 1.44 toe/capita in 1996, and it has then stabilised at that level reaching 1.49 toe/capita in 2015 (Ritchie and Roser 2020). It is still very low compared to the EU-28—3.11 toe/capita or the USA—6.80 toe/capita (Salimov 2018). Therefore, the identification of obstacles in the transition to renewable and sustainable energy and a search for incentives for a “just transition” are analysed based on different case studies. It may also be important for EU policy since in the EU Recommendation from 2018 it was underlined that Azerbaijan—due to its capabilities and geographical location—can play a key role in contributing to Europe’s energy security (RECOMMENDATION No 1/2018 OF THE EU-AZERBAIJAN COOPERATION COUNCIL, 2018).

In Poland, on the other hand, the main document dealing with RES is the Act on Renewable Energy Sources (Act on Renewable Energy Sources of 20 February 2015. Journal of Laws of 2018, item 2389). Due to the fact that Poland is an EU member state, directives dedicated to this topic are implemented in national legislation (like Directive on the promotion of the use of RES) (Directive 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council, 2018). The Directive sets a target common to all Member States that by 2030 the share of energy from renewable sources (RES) in gross final consumption of energy in the EU should be at least 32% (in addition, the 2020 target of 20% share of energy from RES in EU energy consumption is maintained). The new regulations do not introduce sub-targets for individual countries in terms of target shares of energy from renewable sources in final energy consumption (energy mixes of individual countries will be determined by them individually). The Renewable Energy Sources Act (together with amendments) has introduced significant changes in Poland. They mainly concern the energy auctioning system (guarantee of energy repurchase at a fixed price even for 15 years), possibility to burn wood in power plants, and implementation of programs supporting construction of RES installations (especially by private persons). The effect of the introduction of this law was, among others, the support of more than 2,000 installations (in 2016–2019), which produced energy in the auction system with a total value of about 10 billion Euro (154TWh), and the total installed capacity of RES installations reached at the end of Q2 2020 about 11GW (including micro-installations). Despite this, Poland has not achieved the required 15% share of RES in the energy mix, but according to the government this target is achievable in 2021 or 2022. As a result of Poland’s transformation over the past 60 years, total CO2 emissions have declined, increasing from about 200 to about 327Mt (with 1980 being Poland’s reference year for calculating EU targets, where it emitted about 470Mt of CO2) (Najwięksi emitenci CO2—niechlubny ranking 2019), which translates into primary energy production of 1.7 toe/capita (Poland in figures 20202020) (2017).

Energy sources in Azerbaijan and Poland

To determine the transition to a green economy, it is necessary to define access to energy resources and the possibility of diversifying the structure of energy production. The Republic of Azerbaijan is characterised by good access to conventional fuels (especially crude oil), which have been used for centuries and even for millennia. Abundant oil reserves were an integral part of everyday life, and this was observed by medieval travellers. In the nineteenth century, Azerbaijan was a leader in the oil and gas industry, as evidenced by the drilling of the first oil well in Bibi-Heybat in 1846 (Vidadili et al. 2017). In a similar manner, Poland has a large energy infrastructure based on its own coal deposits built up since the 1950s, and coal still has a dominant position in the Polish energy sector (Table 1).

Proven reserves represent the quantity of resources that are expected to be extracted based on a geological analysis, involving the existing equipment and under the existing operating conditions. RES reserves can be determined by the so-called technical potential (e.g. the amount of energy that can be extracted from the sun—this amount increases with the development of technology, but it is important that this energy is economically profitable—the so-called economic potential).

Azerbaijan’s energy reserves mainly consist of oil and natural gas, as proven oil reserves are estimated to be 7 billion barrels, whereas the yearly average production is about 44 million tons. In the case of natural gas, it is 2.1 trillion m3 of proven reserves, whereas average production is about 16.75 billion m3 (Energy: About energy balance of Azerbaijan in 2018). As expected, annual oil production in Azerbaijan, which is the main income of the country, has entered into a phase of decline (Table 2), and this has created a potential challenge for developing RES in the years ahead.

Poland has a completely different energy mix to Azerbaijan, but also produces energy based on conventional sources. The largest energy reserves come from coal (hard coal and lignite) and these are about 1,055 billion tons. Annual coal production is very high (55.2 million t—average from last 12 years) but is constantly falling (in contrast to world production). Crude oil and natural gas are also produced in Poland; however, they are mainly imported in large quantities from abroad (mainly from Russia)—national resources are insufficient. RES (mainly biomass, geothermal, wind, water and solar energy) are constantly developing in Poland; however, the potential for their use is relatively small.

While approximately 65Mtoe of energy is produced annually from oil and natural gas in Azerbaijan, these being the main energy sources of the country, annual consumption is only 14.3 Mtoe of energy products, including both crude oil (32%) and natural gas (65%) which are also the most important export products. In Poland, about 103.4 Mtoe of primary energy products was used, primarily solid and liquid fossil fuels (78.7%), natural gas (14.2%) and RES (5.5%) (Tables 1 and 2) (Azerbaijan’s country-wide electricity blackout 2018).

A direct comparison of energy consumption does not reflect the conditions prevailing in the markets of these countries, hence the correlation of energy consumption (toe) with GDP growth in 1990–2018 (Fig. 1). As can be seen, the correlation showed a significant reduction in energy consumption in terms of Azerbaijan’s GDP, while in the case of Poland a slight downward trend is visible. This situation is due to the fact that Azerbaijan is a developing country and its GDP increased more than 5 times in the period indicated with a decrease in energy consumption of about 36%. By contrast, Poland has recently been included in the group of developed countries and its GDP has grown almost 9 times and its energy consumption has also increased by 1%. Currently, energy consumption figures in these countries are 60.7 GJ/cap (Azerbaijan) and 115.5 GJ/cap (Poland). Although seemingly much more energy is used in Poland, it should be noted that it is largely used for heating, while some countries need little or no heat at all. It is worth noting that the rates of energy consumption per capita (in 2018) in the world range from 9.0 (Bangladesh) to 749.7 GJ (Qatar), with a world average of 76.0 GJ (BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019).

Correlation of energy consumption with GDP (toe/1000 US$). Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 68th edition, 2019 and The world data bank (Database: https://data.worldbank.org/country/)

Energy resources and electricity generation

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan is one of the key countries in the Caspian region that exports crude oil to global energy markets. However, the discovery of huge natural gas reserves on its offshore territory, the start of negotiations with Turkmenistan to establish a legal framework for constructing the Trans-Caspian Pipeline, and recently signed gas agreements have also made Azerbaijan a major natural gas exporting country. Nowadays, supplying natural gas to European markets through the Southern Corridor is the main focus of Azerbaijan’s energy policy. The Southern Corridor, a central part of the country’s energy diversification policy, is the only westward route for exporting hydrocarbons from the Caspian (Akiner & Aldis 2004).

Supplying natural gas through pipelines creates a long-term linkage and increases interdependency between suppliers and consumers, which in turn makes the process more vulnerable from the political point of view. By pursuing a multi-dimensional energy policy, Azerbaijan has taken a cautious and balanced approach, where political interests along with economic interests play a key role in defining priorities within long-term energy projects.

There are 30 power plants operating within the country with an overall 6,402 MW installed power capacity. If operated with full capacity and all hours of the year, 56.08 TWh could be produced. It is worth mentioning that average demand for electricity is 22.4 TWh/year, which is 40% of the installed maximum output in the years 2007–2017 while peak demand was 24.7 TWh in the two consecutive years starting from 2014. In electricity generation, fossil energy sources, in particular natural gas, provide 91.2% of supply against 8.8% for all RES, and of this, 8.4% is supplied by hydro stations. Figure 2 illustrates yearly electricity production and installed power capacity in the period 1913 to 2017. It can be seen from the figures that there was a miniscule reduction in electricity generation within 10 years starting from 1990, but there were major reductions in installed capacity in years concerning from 1990 to 1995 and from 2005 to 2010.

Electricity generation and installed electric power capacity in Azerbaijan. Source: Own study based on State Statistical Committee of Azerbaijan; Eurostat, Energy balance sheets 2017 DATA, 2019 edition

Poland

In Poland, about 4,400 PJ of primary energy is generated annually, which is mostly produced from hard coal and oil (to a lesser extent from natural gas, lignite and RES). Poland is mainly an importer of energy resources, despite having huge deposits of mainly hard coal and lignite. The demand for these raw materials is mainly covered from domestic resources; however, imports are higher than exports (331.9 to 195.2 PJ respectively). The use of these raw materials (especially lignite) will be difficult due to the need to meet climate and environmental policy objectives (Energii 2040).

Poland has no large reserves of oil and natural gas; therefore, domestic consumption is mainly covered by imports from abroad (imports are 96% and 78% respectively). Measures to ensure this are required for the sake of the country’s energy security.

RES (biomass, biogas, solar and wind energy), whose availability is usually evenly distributed across the country, are also used for energy purposes. Poland also uses geothermal energy, whose availability is related to the presence of groundwater (mainly in the southern part of the country). On the other hand, hydro resources are among the smallest in Europe and therefore only make a minor contribution.

In Poland, there are 17 Combined Heat and Power (CHP) plants, 33 power plants and 18 hydroelectric power plants from which electricity is obtained and whose annual consumption is about 171 TWh and this is mainly covered by domestic power plants. Most is provided using hard coal and lignite; however, the share of RES and natural gas is becoming increasingly important. Due to international obligations, a further increase in the contribution of RES to the energy balance is expected. Figure 3 illustrates yearly electricity production and installed power capacity in the period from 1946 to 2019.

Electricity production and installed power capacity in Poland. Source: Own study based on Kwinta W., Energetyki polskiej droga do współczesności, Polska Energia, 2012; KSE, Raport 2019: Access (20.03.2020): https://www.pse.pl/dane-systemowe/funkcjonowanie-rb/raporty-roczne-z-funkcjonowania-kse-za-rok/raporty-za-rok-2019

The examples of Azerbaijan and Poland show a steady increase in generation capacity and energy production associated with the economic development of the two countries. The transition to a green economy should be accompanied by the construction of new power plants based on environmentally friendly technology, as well as a thorough modernisation of old power plants, which should be the goal of national policy (Sachs et al. 2019). Notwithstanding the state guidelines, some financial sector institutions have tried to support the transformation of the energy sector. An example is found in the activities of mBank, which, since 2019, has no longer been financing the construction of new coal-fired units, at the same time trying to increase its share in the green energy sector.

Transition to renewable energy

Over the past century, there has been a large increase in the potential for renewable energy production. As a result of technological development, programmes supporting the development of renewable energy, and measures to increase energy security, a significant decrease in the costs of RES technology can be observed. Popularising RES can contribute to achieving social, economic and environmental benefits, as well as to creating a more diverse and stable electricity sector and being an engine of economic growth. A reflection of these trends can also be observed in the case of the two countries in the Soviet sphere of influence analysed (Azerbaijan, Poland), which were chosen as examples of developing and developed countries. The analysis of strategic documents of both countries showed that they are planning to build new generation facilities mainly based on RES.

In the Polish National Energy and Climate Plan for the years 2021–2030, there are 5 targets including increasing RES and diminishing GHG emissions (Fig. 4). It is estimated that RES in heating and cooling will increase by an average of 1.1 percentage points per year. In transport, a 14% share of renewable energy is expected to be achieved by 2030. The RES share in electricity production will increase to approx. 32% in 2030. To enable the achievement of the above-mentioned targets, it is planned to support RES in the form of a continuation of existing and creation of new support and promotion mechanisms. It is also planned to increase the use of advanced biofuels, introduce offshore wind energy and increase the dynamics of development of renewable energy micro-installations.

Targets in the Polish National Energy and Climate Plan (https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/documents/pl_final_necp_summary_en.pdf). Source: Polish National Energy and Climate Plan, 2020

On the basis of the climate agreement signed by Azerbaijan, the country is to reduce its emissions by 2030 (the power sector is responsible for 85% of emissions). Renewable energy is a relatively new sector in Azerbaijan and still faces many challenges; however, the government has expressed a will to develop RES and stressed that the country’s goal is to increase the share of renewable energy and diversify energy production. On the basis of the draft versions of these documents (e.g. The Strategic Roadmap for specific capacities), potential targets have been identified, among which are the achievement of a share of 35–40% of renewable energy in the total energy stream by 2030 (Table 3). Diversification of Azerbaijan’s energy system is mainly to be achieved through the construction of new wind and hydropower plant. Azerbaijan has extensive renewable energy potential with wind, solar and hydropower being particularly promising. The technical potential for hydropower plants (HPP) is very large—HPP is the second largest source of electricity generation at a national level, and there is potential for their electricity output to contribute up to 14.6% of supply (Yusifov 2018).

Plans to change the energy mix of Azerbaijan and Poland are ambitious and assume a reduction in fossil fuel consumption of about 10% every 5 years. However, given Poland’s current situation, achieving a 71% share of fossil fuels in 2020 seems unrealistic as does the achievement of subsequent objectives. Azerbaijan’s plans, despite a more favourable situation related to RES potential, also seem far from being realistic. For certain, one of the main reasons for this is, in both cases, the instability of the law and the lack of sufficient support instruments.

PESTEL analysis of the transition towards renewable and sustainable energy in Azerbaijan and Poland

In order to assess the possibility of transitioning to sustainable and renewable energy in Azerbaijan and Poland, a PESTEL analysis was carried out for both countries. In this case, the PESTEL analysis concerns the assessment of the macroeconomic environment of an energy sector. It consists in the description of 6 key groups of factors: political, economic, social, technological, environmental and legal. The main assumption of the PESTEL analysis is to discuss and concider the future actions in detail and take relatively quick actions aimed at its correct shaping (Rialland and Wolf 2009).

This analysis is also used to create context for further research and was carried out on the basis of the data presented in the previous parts, international relations and trade, as well as an examination of strategic documents and the supporting instruments used by Azerbaijan and Poland (Table 4).

The first step of the analysis was to identify the issues that affect the implementation of sustainable renewable energy systems and classify them into six groups. This stage was based on a detailed analysis and synthesis of knowledge in the field of renewable energy sources, taking into account the main assumptions of the authors. Then, in each group, a constant number of elements were identified which were considered the most important for the development of renewable energy. For this purpose, scientists brainstormed. The brainstorming was moderated by the authors. The selected elements were then included in the analysis below. Brainstorming was conducted in a group of about 150 experts composed of academics and entrepreneurs (which took place during a conference organised by the Polish Ministry of Entrepreneurship and Technology in 2019). They were professionally involved in the design, construction and operation of drainage energy sources with many years of experience in this field. The scientific community was represented by people with a recognised reputation and outstanding scientific achievements in the field of sustainable renewable energy.

The RES sector is a fast-growing economic sector worldwide, including Azerbaijan and Poland. However, as indicated above, this development is accompanied by a number of opportunities and threats. Political factors relating to RES development in Poland, despite the fact that it can be considered relatively neutral, create a number of opportunities which mainly result from its membership of European Union structures. This allows active participation in the research sphere, as well as stability of the political system. However, due to legislation that is too extensive and has low effectiveness in the practical implementation of political objectives, it is a considerable threat which significantly slows down RES development and the fulfilment of climate obligations. In turn, both the lack of Azerbaijan’s membership of similar structures which could have financially supported and helped develop research into RES and the natural monopoly in the energy market are factors which strongly slow down the chances of developing this market. A significant obstacle to the implementation of innovative energy solutions is institutional barriers, narrow business horizon and lack of communication between different entities (Nanekely et al. 2016; Trapp et al. 2017). Improved cooperation could increase the effectiveness of implementation of new solutions and spending of funds.

Poland is characterised by good economic conditions for the development of RES research and investment as there is the possibility of obtaining EU funds for this purpose, as well as national support systems which are still developing and accompanied by positive economic development. However, green certificates, which were supposed to be a great opportunity for the development of RES, have not met the hopes placed on them. In particular, the possibility of using external funds is greatly restricted by Azerbaijan; however, the government is trying to support the transfer of expensive technologies and to surround RES with the seeds of a support system. Economic considerations included the benefits of new investments in renewable energy. Schmidt and Hauck (Schmidt and Hauck 2018) noted that the economic aspects of using green infrastructure objects (Hopkins et al. 2018) are related to benefits, cost of investments, salaries and land ownership. Investors face these limitations as well as the benefits of specific solutions. In situations where the maintenance of sustainable infrastructure is financially supported, the application of appropriate solutions will also contribute to creating and securing jobs (Schmidt and Hauck 2018).

Azerbaijan’s social environment is also characterised by poor access to information, but the Memorandum of Understanding signed with BP provides a number of opportunities to improve this situation. The situation in Poland, on the other hand, is quite different, as the country is well computerised and has access to the latest information and technologies, e.g. through cooperation within the EU, and additionally, the creation of dedicated RES studies supportss this process. The elements that influence the development of sustainable energy sources also include the tendency of society to use innovative solutions in the field of renewable energy sources. The global trend to reduce environmental impacts may contribute to developers limiting themselves to air pollution only. It is worth noting here that although the use of RES helps to reduce emissions, locally, it may have significant impacts (e.g. noise, landscape change, wastewater from biogas plants, particulates from biomass combustion). Therefore, each investment should be preceded by a multifaceted environmental impact assessment in a long-term perspective (e.g. using the life cycle assessment method). That is why some economic circles are highlighting the importance of reducing emissions in financing energy technologies. It is essential that governments and international institutions develop criteria to identify and prioritise environmentally friendly energy technologies based on the concept of sustainable development (Twidell and Weir 2006). The success of such activities depends on the awareness and willingness of society to implement innovative and environmentally friendly solutions (Sun and Hall 2016). From such a point of view, it is important to create an appropriate incentive, an incentive system combined with relevant socio-environmental issues (Cettner et al. 2014; Madsen et al. 2017).

Technological factors, such as the possibility of knowledge transfer, the high efficiency of RES installations and a considerable potential for photovoltaic production in Poland, which is lacking in the other country, constitute a significant opportunity for the development of RES in Poland. The poor condition of power grids as well as the limited scope of cooperation between science and business is also a major threat in both countries being examined.

Both Poland and Azerbaijan have a large supply of energy resources (coal or oil and gas), which makes them natural sources of energy in these countries and at the same time poses a considerable challenge due to the conventional fuels lobby. Also, the signing of climate commitments makes certain commitments to these countries in terms of inter alia reducing emissions and increasing the share of energy from RES. In this respect, Azerbaijan has better access to RES (especially the sun) while in Poland the biomass market is undergoing significant development.

Taking into account legal factors, it should be noted that strategic documents are being developed and updated in both countries. Despite this, the existing documents in Azerbaijan are of a poor standard and are not properly coordinated, which is further compounded by the corrupt system. In Poland, on the other hand, despite an extensive legal system, the administration is not working effectively, which translates into poor implementation of the objectives adopted.

Conclusion

Development is associated with an increase in energy consumption. Despite the fact that the Earth has large energy reserves, which increase with the development of technology, pollution also increases. The reason for this is mainly the use of fossil fuels for energy production, which generates huge amounts of emissions during its combustion. Therefore, in order to reduce the impact of energy production on the environment and the depletion of resources, it is necessary to transform the energy market through diversification towards renewable energy. This is a transformation in which renewable and conventional sources support each other, creating a beneficial effect on the country’s potential and the environment. Such a transformation, apart from investments in infrastructure enabling the acquisition of green energy, also requires the planned construction of new and the modernisation of existing network infrastructure. Increasing network performance will contribute to reducing transmission losses and will also increase the possibility of connecting alternative and distributed power sources to it.

At the current rate of fossil fuel consumption, the approximate lifetime of the world’s reserves is as follows: for petroleum—50 years, natural gas—52.8 years and coal—153 years. Therefore, we must conserve, limit, innovate, or learn to live without fossil fuel resources which pollute the environment.

The results of the PESTLE analysis showed that both Azerbaijan and Poland face significant challenges in diversifying their energy system. Azerbaijan is a developing country, an energy-independent and whose economy is almost entirely based on fossil fuels (similar to Poland a dozen or so years ago). However, despite this, it has great potential for transformation towards a renewable economy, which is partially limited by the inability to use the Caspian Sea for wind farms due to the lack of agreement with neighbouring countries.

The short-, medium- and long-term goals of this country development have been set out in strategic road maps that indicate that by 2030 renewable energy will account for 35–40% of the total electricity mix. Relevant government policy is also extremely important for transformation, which has stated that it wants to obtain 20% of its electricity generation from renewables in the years to come. Currently, the Ministry of Energy is in the process of developing legislation which will support the development of solar and wind energy projects at selected advantageous sites around the country, the first effects of which can already be seen.

Considering that Azerbaijan’s budget is dependent on oil prices (resulting in lower state budget revenues), government investment in renewable energy is limited. Private sector interest in RES development is low, which is also due to low rates of return. It follows that the government must create an attractive environment for private entrepreneurs to invest in RES, which can contribute to the UN Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Agreement (2015).

Poland is a country with a stable political system, where economic growth is recorded, which positively influences the scientific and research sphere. The energy mix of this country (like that of Azerbaijan’s) is based on fossil fuels (mainly coal—about 80%), which means that the country also has a high potential for change towards RES. Polish international commitments create both imposes obligations and development opportunities for this country (e.g. by possibility of financing research and wide access to modern technologies).

It is also important to note that frequent legislative changes in Poland in the field of RES and the lack of a stable support system make it often unprofitable for private investors, both individual and entrepreneurs, which hampers the development of this sector (e.g. by lack of predictable regulations facilitating economic decisions, oversupply of green certificates affecting the liquidity of RES installations—a significant drop in prices of certificates). Regardless of that, many companies decide to invest in RES for the sake of international cooperation and improving their image as environmentally friendly company, or improving existing technology by implementing their own ideas. In addition, analysis of the current legal system has shown that regulations related to onshore wind farms are more stringent, hindering its development in favour of offshore wind farms.

Due to the fact that coal power industry has strong roots in Poland (especially in Silesia region), there is a strong opposition to RES development caused by the liquidation of coal mines, related distribution structures and thus numerous jobs, as well as the impact of RES on local ecosystems, as pointed out by a strong coal power industry lobby. It is also worth noting the condition of the transmission infrastructure, which is largely outdated, resulting in significant energy transmission losses (the grid is gradually being replaced), which favours the use of distributed RES and reduces transmission losses.

In conclusion, it should be pointed out that the PESTEL analysis conducted showed that despite some problems, RES has a chance for further development in Poland, especially through friendly legal regulations, financial subsidies, development of domestic producers of RES installations, and the education of society. On the other hand, in Azerbaijan, despite more problems of a different nature, RES is constantly being developed and supported by the government. However, compared to Poland, it requires much more support and foreign cooperation (e.g. technology sharing, international agreements and support).

In order to achieve the goals indicated in the road map regarding the level of renewable energy use in subsequent years, legal, financial and technical challenges (no legal regulations regarding RES, simplification of technology transfer procedures, lack of financial resources and high interest rates, obsolete infrastructure) must be removed and awareness of the renewable energy sector should be increased.

References

Aydin U., Energy insecurity and renewable energy sources: prospects and challenges for Azerbaijan, ADBI Working Paper Series, No. 992, Asian Development Bank Institute, 2019

Azerbaijan’s country-wide electricity blackout: problems, causes, and results, CESD Research Group, Baku 2018.

BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 67th edition, 2018

BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 68th edition, 2019;

BP, Azerbaijani Energy Ministry Sign MoU on Renewable Energy, 2006. Access (20.03.2020): https://www.azernews.az/oil_and_gas/142844.html

Caspian Information Centre. 2013. Azerbaijan: alternative and renewable energy-a business perspective. http://docplayer.net/13640110-Azerbaijan-alternative-and-renewable-energy-a-business-perspective-open-for-business-series.html (accessed 21 January 2019).

Cettner A, Ashley R, Hedström A, Viklander M (2014) Assessing receptivity for change in urban stormwater management and contexts for action. J Environ Manag 146:29–41

Energy: About energy balance of Azerbaijan in 2018, State Statistical Committee of Azerbaijan, Access (20.03.2020): https://www.stat.gov.az/source/balance_fuel/?lang=en

Eurostat, Energy balance sheets 2017 DATA, 2019 edition

IRENA, Renewable capacity statistics 2019

Kordana S, Pochwat K, Słyś D, Starzec M (2019) Opportunities and threats of implementing drain water heat recovery units in Poland. Resources 8:88

Madsen HM, Brown R, Elle M, Mikkelsen PS (2017) Social construction of stormwater control measures in Melbourne and Copenhagen: a discourse analysis of technological change, embedded meanings and potential mainstreaming Technol. Forecast Soc 115:198–209

Muntean M, Guizzardi D, Schaaf E, Crippa M, Solazzo E, Olivier JGJ, Vignati E (2018) Fossil CO2 emissions of all world countries. 2018 Report. JRC SCIENCE FOR POLICY REPORT, Luxembourg 2018

Nanekely M, Scholz M, Al-Faraj F (2016) Strategic framework for sustainable management of drainage systems in semi-arid cities: an Iraqi case study. Water 8:406

Rialland A, Wolf KE (2009) Future studies, foresight and scenarios as basis for better strategic decisions (IGLO-MP2020 working paper, Trondheim)

RECOMMENDATION No 1/2018 OF THE EU-AZERBAIJAN COOPERATION COUNCIL of 28 September 2018 on the EU-Azerbaijan Partnership Priorities [2018/1598], Official Journal of the European Union L 265/18.

Ritchie H, Roser M (2020) “Energy”. Access (20.03.2020): https://ourworldindata.org/energy

Sachs J, Woo WT, Yoshino N, Taghizadeh-Hesary F (2019) Importance of green finance for achieving sustainable development goals and energy security. In Handbook of green finance: energy security and sustainable development, edited by J. Sachs, W.T. Woo, N. Yoshino, and F. Taghizadeh-Hesary. Tokyo: Springer; Access (20.03.2020): https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-981-13-0227-5_13.pdf

Salimov S (2018) Energy indicators for sustainable development of Azerbaijan Republic -economic dimension. European Journal of Sustainable Development 7:1

Akiner S, Aldis A (2004) The Caspian: politics, energy and security. Routledge, 2004. P. 5. (BAKU FIRST OIL)

Schmidt J, Hauck J (2018) Implementing green infrastructure policy in agricultural landscapes – scenarios for Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Reg Environ Chang 18:899–911

Sun N, Hall M (2016) Coupling human preferences with biophysical processes: modeling the effect of citizen attitudes on potential urban stormwater runoff. Urban Ecosyst 19:1433–1454

Trapp JH, Kerber H, Schramm E (2017) Implementation and diffusion of innovative water infrastructures: obstacles, stakeholder networks and strategic opportunities for utilities Environ. Earth Sci 76:15

Twidell J, Weir T (2006) “Wind Power,” in renewable energy resources. Seconded. London and New York: Taylor&Francis; 2006

Smil V (2017) Energy transitions: global and national perspectives; BP Statistical Review of World Energy

Vidadili N, Suleymanov E, Bulut C, Mahmudlu C (2017) Transition to renewable energy and sustainable energy development in Azerbaijan, renewable and sustainable energy reviews. 80

Yoshino N, Taghizadeh-Hesary F, Nakahigashi M (2019) Modelling the social funding and spill-over tax for addressing the green energy financing gap. Econ Model 77:34–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2018.11.018

Yusifov J (2018) Overview of renewable energy developments in Azerbaijan, Baku 2018, Access (20.03.2020): https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Events/2018/May/Azerbaijan-RRA-workshop/2--Mr-Jabir-Yusifov-SAARES--Overview-of-the-energy-sector-and-renewa.pdf?la=en&hash=EF0FFCB2B8F1CB61B92F5528C5A22B54E1B0D16C.

Directive 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources

Najwięksi emitenci CO2—niechlubny ranking, Green Projects, 2019.

Poland in figures 2020, Statistics Poland, Warsaw 2020.

Ministerstwo Energii, Polityka energetyczna Polski do 2040 r. Projekt, Warszawa 2019

Hopkins KG, Grimm NB, York AM (2018) Influence of governance structure on greenstormwater infrastructure investment. Environ Sci Pol 84:124–133

Funding

This work was funded by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange (NAWA) as the part of the project “International cooperation for Rational Use of Raw Materials and Circular Economy” (COOPMIN) which is conducted in the Division of Strategic Research in the MEERI PAS (2019–2020), project no. PPI/APM/2018/1/00003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cholewa, M., Mammadov, F. & Nowaczek, A. The obstacles and challenges of transition towards a renewable and sustainable energy system in Azerbaijan and Poland. Miner Econ 35, 155–169 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-021-00288-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-021-00288-x