Abstract

Introduction

Psoriasis (PsO) is associated with the development of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Patients with PsO often experience pre-PsA musculoskeletal (MSK) symptoms, leading to potential structural damage and substantial disease burden with impact on function. The objective of this study is to describe prevalence rates and evidence of MSK symptoms, including incidence of comorbid PsA diagnosis, in patients newly diagnosed with PsO and identify factors associated with PsA diagnosis.

Methods

This retrospective analysis included administrative claims from the Optum Research Database for adult patients with a new PsO diagnosis between January 2008 and February 2019. Eligible patients had ≥ 2 claims for PsO on unique dates, were aged ≥ 18 years at the date of the first claim with a diagnosis of PsO (index date), and had continuous enrollment with medical and pharmacy coverage for 12 months before (baseline period) and ≥ 12 months following the index date. Primary outcomes were incidence of comorbid PsA diagnosis, prevalence of MSK symptoms other than PsA, and evidence of MSK symptoms collected at baseline and assessed in 12-month intervals through 60 months.

Results

Of the 116,203 patients with newly diagnosed PsO, 110,118 were without baseline comorbid PsA. High prevalence rates of MSK symptoms among patients with only PsO were seen at baseline (47.1%), 12 months (48.2%), and 60 months (82.1%). Patient age, baseline MSK symptoms, and baseline MSK symptom–related healthcare utilization were associated with increased hazard of a PsA diagnosis.

Conclusion

Increased prevalence rates of MSK symptoms and burden are experienced by patients newly diagnosed with PsO through 60 months of follow-up. Several baseline factors were associated with increased risk of PsA diagnosis.

Plain Language Summary

A Study to Look at Symptoms of Muscles, Joints, and Bones in Patients with Psoriasis and Whether They Can Predict a Diagnosis of Psoriatic Arthritis

Psoriasis is an inflammatory skin disease that results in areas of significant itchiness, pain, and scaling, and ultimately decreases patient quality of life. Psoriasis affects approximately 2–4% of the general US population and 1.3–2.2% of the UK population. Some patients with psoriasis may experience musculoskeletal symptoms and may go on to develop psoriatic arthritis. The goal of this study was to determine the frequency of patients with psoriasis who experienced complaints of musculoskeletal pain prior to and/or following their psoriasis diagnosis, and whether these were associated with further probability of developing psoriatic arthritis.

Using a large US-based database with data from approximately 115,000 patients with newly diagnosed psoriasis, we determined the percentage of newly diagnosed psoriasis patients with existing musculoskeletal pain complaints within 12 months of their initial diagnosis. We found that 47% of newly diagnosed patients had previous musculoskeletal pain complaints, with joint pain, back pain, and overall fatigue representing the most common forms. Notably, psoriasis patients with previous joint pain were approximately 50% more likely to develop psoriatic arthritis compared with patients with no previous joint pain. Furthermore, patients with previous other forms of arthritis were nearly twice as likely to develop psoriatic arthritis.

This study provides additional support that existing musculoskeletal pain in patients with newly diagnosed psoriasis may predict the potential future onset of psoriatic arthritis. These findings will help guide primary care physicians, dermatologists, and rheumatologists in understanding the importance of earlier detection of psoriatic arthritis to provide more appropriate care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Limited data exist on prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms in patients newly diagnosed with psoriasis and patient factors that are predictors of psoriatic arthritis diagnosis in early psoriasis. |

This study aimed to describe the prevalence rates of musculoskeletal symptoms in patients with newly diagnosed psoriasis. |

What was learned from this study? |

Musculoskeletal symptoms were increasingly prevalent in patients with psoriasis through 60 months; baseline symptoms were associated with higher risk of psoriatic arthritis diagnosis. |

These findings highlight that physicians should be asking their patients with psoriasis about musculoskeletal complaints and presents an opportunity for primary care providers and dermatologists to collaborate with rheumatologists in the management and care of patients with psoriasis who have musculoskeletal complaints. |

Introduction

Psoriasis (PsO) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that affects approximately 2–4% of the general US population, characterized by skin itching, pain, and scaling [1, 2]. Studies report that up to half of patients with PsO display musculoskeletal (MSK) symptoms, including joint pain, swelling, tenderness, and inflammation [3,4,5,6]. Inadequate PsO disease management can exacerbate MSK manifestations, leading to increased disease burden [4]. MSK symptoms often precede a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) [4, 7,8,9]. PsO is significantly associated with PsA; up to 30% of patients with PsO develop comorbid PsA [2, 10, 11]. Frequently, PsO precedes PsA by 10 years [12,13,14], and many patients with PsA are undiagnosed or underdiagnosed by dermatologists [10]. Patients with PsO can experience pre-PsA MSK symptoms prior to PsA diagnosis, leading to pain and physical disability [15, 16]; however, presence of MSK symptoms in patients newly diagnosed with PsO remains unknown.

PsA, a progressive inflammatory arthropathy, is heterogeneous in clinical presentation and affects multiple aspects of the MSK system. PsA clinical manifestations include peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, nail disease, skin disease, and axial involvement, which can lead to irreversible structural damage, loss of function, and reduced quality of life [5, 15, 17, 18]. Currently, there are no definitive biomarkers or diagnostic tests for PsA, and it is challenging to identify because its symptoms mimic those of other rheumatic diseases [19, 20]. Prompt PsA diagnosis is imperative; a diagnostic delay of 6 months from PsA symptom onset can lead to significantly more radiographic joint damage, worse physical function, and inadequate treatment response [16]. Patients with PsA often experience average diagnostic delays up to 5 years [14, 19, 21], which leads to inadequate patient care [22, 23].

Healthcare providers who evaluate patients with PsO can screen for PsA and reduce diagnostic delays; patients with PsO exemplify a readily identifiable population at risk for disease progression. Despite receiving treatment for PsO, patients often still experience substantial MSK symptom burden, which may be underdiagnosed or undiagnosed [4, 9, 24]. A knowledge gap exists regarding the prevalence and timing of MSK symptoms that may predict a PsA diagnosis; closing this gap could address the unmet need of improving diagnosis timing and treatment response.

This study describes the incidence and burden of MSK symptoms among patients with newly diagnosed PsO and identifies associations between MSK symptoms and a diagnosis of PsA using claims data from a large database. We assessed prevalence and evidence of MSK symptoms at baseline through 60 months from the time of PsO diagnosis to understand the progressive impact of MSK symptoms.

Methods

Study Design and Population

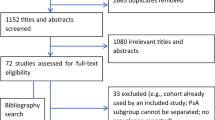

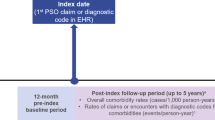

In this exploratory, retrospective study using the Optum Research Database, a large administrative claims database, we identified patients who had a diagnosis of PsO between 1 January 2008 and 28 February 2019 (Fig. S1). The study consisted of three periods (Fig. S2): (1) a 12-month period prior to diagnosis of PsO (baseline); (2) the date of the first claim with a diagnosis of PsO (index date); and (3) a follow-up period starting the day after the index date with a duration of ≥ 12 months. The follow-up period ended when the event of interest (e.g., MSK symptom diagnosis) occurred, when the patient disenrolled from the health plan, or the end of the study period was reached.

Eligible patients were aged ≥ 18 years at the date of the first claim with a diagnosis of PsO (index date) using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code 696.1 and the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes L40.0, L40.1, L40.2, L40.3, L40.3, L40.8, and L40.9; had commercial insurance coverage or were enrolled in Medicare Advantage Part D with ≥ 2 claims for PsO on unique dates; and had continuous enrollment with medical and pharmacy coverage for ≥ 12 months before (baseline period) and following the index date.

Exclusion criteria included ≥ 1 claim for PsO during the baseline period and having unknown/missing demographic information. For incidence of PsA and predictors of PsA diagnosis, patients with ≥ 1 claim for PsA diagnosis (ICD-9-CM: 696.0; ICD-10-CM: L40.50, L40.51, L40.52, L40.53, and L40.59) in any position during the baseline period were excluded.

Administrative claims data from 1 January 2007 to 29 February 2020 were included to capture a 12-month baseline period and a ≥ 12-month follow-up period beyond the identification period. A random 10% sample of patients in the Optum Research Database aged ≥ 18 years as of 1 January 2019, with continuous enrollment with medical and pharmacy coverage from 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2019, was included as a representative control cohort. Because the current study used only deidentified patient records and did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, institutional review board approval was not required to conduct this study. This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Study Variables

Primary outcomes were incidence of comorbid PsA diagnosis (≥ 1 claim with a diagnosis code in any position for PsA), prevalence of MSK symptoms other than PsA [identified with ≥ 1 claim of diagnosis code for arthralgia, myalgia, tendonitis, fasciitis, arthritis, joint stiffness, back pain, enthesitis, synovitis, fatigue (unspecified chronic fatigue, other malaise and fatigue, and other fatigue), and nail dystrophy (specified/unspecified disease of the nail)], and evidence of MSK symptoms collected at baseline and assessed in 12-month intervals through 60 months among patients with continuous enrollment. Evidence of MSK symptoms included diagnosis codes (≥ 1 claim with a diagnosis code in any position for an MSK symptom), prescription medication [≥ 3 consecutive months of treatment with prescription pain medications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, benzodiazepines, opioids, centrally acting skeletal-muscle relaxants, and systemic glucocorticoids)], procedure and/or assessment [≥ 1 claim with Current Procedural Terminology, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS), diagnosis, procedure, or revenue code for joint imaging, chiropractic or osteopathic treatment, or physical therapy], MSK-related healthcare resource utilization [(HCRU) ≥ 1 claim for a healthcare visit to a rheumatologist, orthopedist, chiropractor, physical therapist, osteopath, podiatrist, or sports medicine practitioner], or ambulatory assist device (≥ 1 claim with a HCPCS code for an ambulatory assist device).

Data collected at baseline included patient demographics (age, sex, insurance status), clinical characteristics [follow-up length, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score (predicts 10-year mortality for patients with comorbid diseases; categorized by severity) [25]], comorbid conditions, [which included the top Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) clinical classifications categories; other connective tissue disease defined as AHRQ category 211.XX; enthesopathies; disorders of synovium, tendon, and bursa; and disorders of muscle, ligaments, and fasciae], and comorbid inflammatory conditions.

Data Analysis

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics were analyzed descriptively, stratified by baseline comorbid PsA status, and presented as frequencies (%) for categorical variables and means with standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables. Pearson χ2 tests were used for binary measures, and two-sample t-tests were used for continuous variables. Cox proportional hazards regression modeling was used to determine the relationship between select covariates and PsA diagnosis among patients with PsO only (i.e., without a claim for PsA in any position during the 12-month baseline period). Predictors of interest included baseline demographic characteristics, MSK symptoms, evidence of MSK symptoms, and clinical characteristics (Quan–Charlson comorbidity score, AHRQ comorbidity conditions, and a flag for any inflammatory comorbid condition). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Overall, 116,203 patients newly diagnosed with PsO were included, of whom 110,118 (94.8%) did not have comorbid PsA at baseline (Table 1). The mean (SD) follow-up period for all patients was 1423.8 (917.5) days. Patients with only PsO had a mean (SD) age of 53.7 (16.4) years. Approximately half of patients with only PsO were female (53.0%), and most had commercial insurance (73.7%).

High proportions of patients with only PsO had non-MSK comorbid conditions, including other skin disorders (45.5%), disorders of lipid metabolism (42.9%), and hypertension (42.2%) (Table 1). Over one-third of patients with only PsO (38.4%) had any inflammatory conditions; patients also experienced osteoarthritis (16.6%) and fibromyalgia (4.5%).

Patients with PsO and baseline PsA had demographic characteristics similar to those with PsO only. PsO patients with baseline PsA also had significantly high prevalence of other comorbid conditions and inflammatory conditions at baseline. Compared with patients with PsO only, those with PsO and baseline PsA had a higher prevalence of non-traumatic joint disorders, conditions relating to back problems, and other connective tissue disorders (Table 1).

MSK Symptoms at Baseline among Patients with PsO

A total of 47.1% of patients diagnosed with only PsO experienced any MSK symptoms at baseline (Fig. 1). Arthralgia (22.7%), back pain (20.8%), and fatigue (14.8%) were among the most frequent individual MSK symptoms in these patients. At baseline, 59.4% of patients with only PsO had any evidence of MSK symptoms, 38.4% had an MSK-related procedure and/or assessment, and 32.9% had an HCRU.

Proportions of patients with only PsO with a prevalence and b evidence of MSK symptoms at baseline. HCPCS Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System, HCRU healthcare resource utilization, MSK musculoskeletal, PsO psoriasis. aMSK symptoms were identified from diagnosis codes on medical claims; patients with ≥ 1 claim with a diagnosis code in any position were identified. bPatients were identified by diagnosis code, prescription medication, procedures/assessments, HCRU, or ambulatory assist device. cOne or more claims with Current Procedural Terminology, HCPCS, diagnosis, procedure or revenue code for joint imaging, chiropractic or osteopathic treatment, or physical therapy. dOne or more claims for a healthcare visit to a rheumatologist, orthopedist, chiropractor, physical therapist, osteopath, podiatrist, or sports medicine practitioner. eThree or more consecutive months of treatment with prescription medications for pain. fOne or more claims with an HCPCS code for an ambulatory assist device

MSK Symptom Prevalence and Evidence of MSK-Related Resource Utilization among Patients with PsO at 12 and 60 months of Follow-up

At 12 months, 48.2% of patients with only PsO had any MSK symptom; the most prevalent were arthralgia (24.4%), back pain (21.7%), and fatigue (15.1%) (Fig. 2). Prevalence of all MSK symptoms increased in patients at 24-, 36-, and 48-month follow-ups (Table S1). At 60 months, the proportion of patients with PsO only who experienced any MSK symptom increased to 82.1%, and prevalence of all individual MSK symptoms increased (Fig. 2). The most common MSK symptoms were arthralgia (55.9%), back pain (47.8%), and fatigue (39.9%).

Similar findings were seen for proportions of patients who experienced evidence of MSK symptoms at 12- and 60-month follow-ups (Fig. 3). At 12 months, 60.9% of patients had any evidence of MSK symptoms, followed by procedure and/or assessment (40.9%), and MSK-related HCRU (36.0%). A comparison of prevalence of MSK symptoms and evidence of MSK symptoms (MSK-related procedure and/or assessment and use of an ambulatory assist device) at 12-month follow-up between patients with PsO and a representative control cohort of patients enrolled in the Optum Research Database is presented in Fig. S3. The proportion of patients with evidence of an MSK symptom increased each year to 89.0% at 60 months, with most patients experiencing MSK-related procedures and/or assessments and MSK-related HCRU (75.7% and 66.8%, respectively) (Table S1; Fig. 3).

Proportions of patients with only PsO with evidence of MSK-related resource utilization at 12- and 60-month follow-up. HCPCS Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System, HCRU healthcare resource utilization, MSK musculoskeletal, PsO psoriasis. aPatients were identified by diagnosis code, prescription medication, procedures/assessments, healthcare resource utilization, or ambulatory assist device. bMSK symptoms were identified from diagnosis codes on medical claims; patients with ≥ 1 claim with a diagnosis code in any position were identified. cOne or more claims with Current Procedural Terminology, HCPCS, diagnosis, procedure or revenue code for joint imaging, chiropractic or osteopathic treatment, or physical therapy. dOne or more claims for a healthcare visit to a rheumatologist, orthopedist, chiropractor, physical therapist, osteopath, podiatrist, or sports medicine practitioner. eThree or more consecutive months of treatment with prescription medications for pain. fOne or more claims with an HCPCS code for an ambulatory assist device

The use of advanced therapeutics for PsA or PsO differed significantly among patients with PsO, stratified by baseline comorbid PsA (P < 0.001) (Table S2). Overall, 53.4% of patients with both PsO and PsA received ≥ 1 advanced therapy indicated for PsO and PsA compared with 10.9% of patients with only PsO. Regarding the use of conventional therapeutics, cyclosporine use was minimal among patients with PsO only (0.6%) and comorbid PsA (0.7%), although usage of methotrexate was greater among patients with comorbid PsA (37.7%) compared with patients with PsO only (7.2%).

Timing of MSK symptom occurrence and PsA diagnosis among patients with only PsO

Patients with only PsO had a median [95% confidence interval (CI)] time to occurrence of MSK symptoms of 659.0 (651.0–666.0) days (Fig. S4). Median (95% CI) time to evidence of MSK symptoms was 438.0 (433.0–442.0) days.

In the overall PsO-only cohort with ≥ 1 MSK symptom, the cumulative PsA rates at 1 year, 2 years, and 5 years following index diagnosis were 5.2%, 7.5%, and 12.3%, respectively. In the PsO-only cohort with or without baseline MSK symptoms, the corresponding percentages were 3.7%, 5.6%, and 9.7%, respectively (Table S3).

Predictors of PsA Diagnosis among the PsO-Only Cohort

Patient age at PsO diagnosis was significantly associated [hazard ratio (HR) [95% CI]] with increased likelihood of a PsA diagnosis, as seen among patients aged 30–39 years (1.32 [1.19–1.46]), 40–49 years (1.54 [1.40–1.70]), and 50–59 years (1.36 [1.23–1.50]) versus those aged 18 to 29 years (all P < 0.001) (Fig. 4). A significant positive association (HR [95% CI]) was also observed between baseline CCI scores of 3 and a PsA diagnosis (1.17 [1.04–1.31]; P = 0.009) versus a CCI score of 0. Additionally, presence vs absence of baseline MSK symptoms was significantly associated (HR [95% CI]) with increased hazard of a PsA diagnosis, including arthralgia (1.48 [1.41–1.57]; P < 0.001), myalgia (1.14 [1.05–1.24]; P = 0.001), tendonitis (1.33 [1.21–1.45]; P < 0.001), fasciitis (1.18 [1.05–1.32]; P = 0.005), arthritis (1.97 [1.82–2.12]; P < 0.001), fatigue (1.13 [1.07–1.19]; P < 0.001), and nail dystrophy (1.20 [1.03–1.41]; P = 0.024). Similarly increased hazard (HR (95% CI)) of receiving a diagnosis of PsA was also seen among patients who had baseline evidence of MSK symptoms such as prescription pain medications (1.40 [1.32–1.48]; P < 0.001) and MSK-related procedures, assessment, and/or HCRU (1.28 [1.21–1.35]; P < 0.001).

Proportional hazards model of PsA diagnosis among patients with only PsO. AHRQ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, GI gastrointestinal, MSK musculoskeletal, PsA psoriatic arthritis, PsO psoriasis, ref reference, CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio. aCovariates in the model included demographic characteristics (age group, sex, insurance type, and geographic region). MSK symptoms were defined using diagnostic codes (arthralgia, myalgia, tendonitis, fasciitis, arthritis, joint stiffness, back pain, enthesitis, fatigue, and nail dystrophy), evidence of MSK symptoms (prescription medication; procedure, assessment, and/or healthcare utilization; and ambulatory assist device), and clinical characteristics (Quan–Charlson comorbidity score, AHRQ comorbidity conditions, and a flag for any inflammatory comorbid condition). bHRs are for the presence of the comorbidity/condition versus the absence

Several factors were associated with decreased hazard of a PsA diagnosis (HR [95% CI]), including an age of ≥ 70 years (0.64 [0.57–0.73]; P < 0.001) versus an age of 18–29 years; male versus female sex (0.95 [0.91–0.99]; P < 0.028); baseline presence versus absence of other skin disorders such as atopic dermatitis, eczema, and contact dermatitis (0.87 [0.84–0.91]; P < 0.001); and use versus non-use of an ambulatory assist device at baseline (0.60 [0.55–0.65]; P < 0.001).

Discussion

In this retrospective study, patients diagnosed with PsO and followed for ≥ 12 months had increased prevalence and evidence of MSK symptoms over time and experienced MSK-related HCRU before diagnosis of MSK symptoms. Among patients with only PsO (i.e., without a diagnosis of PsA at baseline), 3.7%, 5.6%, and 9.7% of patients were diagnosed with PsA at 1, 3, and 5 years, respectively, with a median time to development of PsA of 1.2 years; these rates are similar to those previously reported by our group and others [24, 26,27,28,29]. Patient factors such as ages 30–59 years, presence of baseline evidence of MSK symptoms, or baseline inflammatory comorbid conditions were significantly associated with increased hazard of a PsA diagnosis.

This study provides a comprehensive assessment of MSK symptom prevalence among patients with newly diagnosed PsO followed up for an extended period. Similar analyses assessed MSK symptoms in patients with PsO prior to receiving a PsA diagnosis [4, 29,30,31,32]; a prospective cohort study using medical records and patient survey data reported that 23% and 21.5% of patients with PsO experienced baseline arthralgia and back pain, respectively [4]. Another prospective cohort study of patient survey and medical records for patients with PsO found that 41% and 35% of patients reported baseline arthralgia and nail disease, respectively [31]. Additional studies demonstrated through ultrasonography that subclinical entheseal abnormalities are present in asymptomatic patients with PsO, which may serve as another predictor for the development of PsA [29, 32]. However, these studies focused on patients with established PsO, with mean disease durations of as high as 15.8 and 20.1 years [4, 31]. Our analysis is unique in assessing the progression of MSK burden from patients with a new PsO diagnosis as the index date.

Approximately half of patients in our study experienced MSK symptoms at diagnosis. By 60 months, most patients experienced MSK-related burden, indicating their PsO was not well controlled, and they may need additional intervention or care. Patients with PsO and comorbid PsA at baseline continued to face MSK burdens at potentially higher rates than patients with PsO only, even though these patients also had high rates of advanced therapy utilization throughout follow-up, suggesting that new MSK symptoms continued to develop, and existing symptoms were exacerbated. Furthermore, this study data was collected from 2007 to 2020, when the treatment landscape for PsO and PsA changed considerably. The development and approval of new therapeutics for these indications during this time frame included some agents reported to affect the occurrence of PsA in patients with PsO; future analyses should be conducted to assess the impact of newer treatments on the prevalence of MSK symptoms and diagnosis of comorbid PsA.

Our study demonstrates characteristics of patients with only PsO that may predict a future PsA diagnosis. Previous studies have reported that the presence of MSK symptoms is associated with development of PsA. Eder et al., described above, suggested that among patients with PsO, female sex, baseline arthralgia, and high stiffness scores were strong predictors for PsA development [4]. A meta-analysis of four prospective cohort studies reported patients with PsO with arthralgia experienced an increased risk of developing PsA [33]. Similar to prior studies, our results showed that the presence of MSK symptoms, such as arthralgia, tendonitis, and arthritis, was significantly associated with increased risk of PsA diagnosis. Furthermore, this study identified additional factors associated with PsA diagnosis, including age (30–59 years), certain comorbidities including other skin disorders, eye disorders, and benign neoplasms, and evidence of MSK conditions prior to PsO diagnosis (prescription pain medication use and HCRU). Patients and clinicians alike should be aware of these symptoms and factors as potential signs of subclinical PsA or predictors of PsA development among patients with PsO. Our observation that non-traumatic joint disorders, conditions relating to back problems, and other connective tissue disorders at baseline occurred more frequently among patients with a PsA diagnosis highlights the importance of vigilance among clinicians regarding the development of MSK symptoms, even those not apparently related to psoriatic disease. Although approximately 20% of patients were ≥ 70 years of age, older age was associated with decreased risk of PsA development. This is consistent with previous studies showing decline in incidence of PsA among patients aged ≥ 60 years, which may be attributed to increased comorbidity burden in aging populations that could mask or obfuscate a diagnosis of PsA [34, 35]. Our results corroborate available data regarding MSK symptoms as predictors for PsA diagnosis and highlight the importance of early patient monitoring during subclinical phases of PsA to identify patients with PsA earlier to reduce diagnostic delays.

This analysis should be interpreted within the context of the study limitations. Patients were required to be enrolled in commercial or Medicare Advantage health plans, a requirement that may not reflect the general population of patients with PsO and limits the generalizability of findings. Data were derived from patient medical claims, which do not include detailed information on clinical characteristics (i.e., disease severity) or information about time between onset of symptoms and diagnosis of PsO. Furthermore, medical claims lack validation and are therefore subject to underreporting or incorrect coding and diagnosis. To minimize the impact of this limitation, patients were required to have a prespecified number of PsO-specific claims. Despite excluding patients with a PsA diagnosis from baseline, it is still possible that some physicians may have coded for PsO only in patients who had both PsO and PsA, leading to overestimation of MSK conditions at baseline. Likewise, the potential for presence of osteoarthritis or fibromyalgia could serve as confounders for experiencing MSK symptoms. In addition, patients were not necessarily evaluated or managed by a rheumatologist following development of MSK symptoms, and it may be possible that some patients with MSK symptoms did have PsA without having a diagnosis code for it at baseline. Imaging analyses including X-ray, MRI, and ultrasound were not included in this analysis and could provide additional evidence for transition to PsA in future studies. Some study outcomes (e.g., prescription medication use and HCRU) cannot be attributed to a specific symptom; however, results still provide useful information about MSK-related burden and may set the foundation for future studies using diagnosis codes (e.g., predictive modeling). Finally, no direct comparison was made between MSK symptoms in the groups studied here versus those present in a control group of patients without PsO or PsO and PsA.

Conclusion

In this exploratory study, patients with PsO had increased prevalence rates and evidence of MSK symptoms through 60 months. Diagnosis of PsA was significantly associated with patient age, prescription pain medication, arthritis, and arthralgia. Our results suggest that patients with MSK symptoms should be screened for PsA to prevent diagnostic and treatment delays, and that physicians should be asking their patients with PsO about any MSK complaints during follow-up visits. Furthermore, these findings highlight an opportunity for primary care providers and dermatologists to collaborate with rheumatologists in the management and care of patients with PsO who have MSK complaints.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

References

Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5):826–50.

Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen LE, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(1):251-65 e19.

Karreman MC, Weel AE, van der Ven M, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in primary care patients with psoriasis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(4):924–31.

Eder L, Polachek A, Rosen CF, Chandran V, Cook R, Gladman DD. The development of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis is preceded by a period of nonspecific musculoskeletal symptoms: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(3):622–9.

Kavanaugh A, Helliwell P, Ritchlin CT. Psoriatic arthritis and burden of disease: patient perspectives from the population-based multinational assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (MAPP) survey. Rheumatol Ther. 2016;3(1):91–102.

Lebwohl MG, Kavanaugh A, Armstrong AW, Van Voorhees AS. US perspectives in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: patient and physician results from the population-based multinational assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (MAPP) survey. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17(1):87–97.

Savage L, Tinazzi I, Zabotti A, Laws PM, Wittmann M, McGonagle D. Defining pre-clinical psoriatic arthritis in an integrated dermato-rheumatology environment. J Clin Med. 2020;9(10):3262.

Ogdie A, Rozycki M, Arndt T, Shi C, Kim N, Hur P. Longitudinal analysis of the patient pathways to diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021;23(1):252.

Faustini F, Simon D, Oliveira I, et al. Subclinical joint inflammation in patients with psoriasis without concomitant psoriatic arthritis: a cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(12):2068–74.

Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Papp KA, et al. Prevalence of rheumatologist-diagnosed psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis in European/North American dermatology clinics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(5):729–35.

Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Helliwell P, et al. Comparative performance of psoriatic arthritis screening tools in patients with psoriasis in European/North American dermatology clinics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(4):649–55.

Gottlieb AB, Mease PJ, Mark Jackson J, et al. Clinical characteristics of psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis in dermatologists’ offices. J Dermatolog Treat. 2006;17(5):279–87.

Tillett W, Charlton R, Nightingale A, et al. Interval between onset of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis comparing the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink with a hospital-based cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(12):2109–13.

Karmacharya P, Wright K, Achenbach SJ, et al. Time to transition from psoriasis to psoriatic arthritis: a population-based study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2022;52:151949.

Lebwohl MG, Bachelez H, Barker J, et al. Patient perspectives in the management of psoriasis: results from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(5):871-81.e1-30.

Haroon M, Gallagher P, FitzGerald O. Diagnostic delay of more than 6 months contributes to poor radiographic and functional outcome in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(6):1045–50.

Gladman DD, Mease PJ, Healy P, et al. Outcome measures in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(5):1159–66.

Orbai AM, de Wit M, Mease P, et al. International patient and physician consensus on a psoriatic arthritis core outcome set for clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(4):673–80.

Gottlieb A, Merola JF. Psoriatic arthritis for dermatologists. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31(7):662–79.

Rida MA, Chandran V. Challenges in the clinical diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis. Clin Immunol. 2020;214: 108390.

Ogdie A, Nowell WB, Applegate E, et al. Patient perspectives on the pathway to psoriatic arthritis diagnosis: results from a web-based survey of patients in the United States. BMC Rheumatol. 2020;4:2.

Gladman DD, Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V, Cook RJ. Do patients with psoriatic arthritis who present early fare better than those presenting later in the disease? Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(12):2152–4.

Theander E, Husmark T, Alenius GM, et al. Early psoriatic arthritis: short symptom duration, male gender and preserved physical functioning at presentation predict favourable outcome at 5-year follow-up. Results from the Swedish Early Psoriatic Arthritis Register (SwePsA). Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(2):407–13.

Wilson FC, Icen M, Crowson CS, McEvoy MT, Gabriel SE, Kremers HM. Incidence and clinical predictors of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(2):233–9.

Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–82.

Merola JF, Tian H, Patil D, et al. Incidence and prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis stratified by psoriasis disease severity: retrospective analysis of an electronic health records database in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(4):748–57.

Eder L, Haddad A, Rosen CF, et al. The incidence and risk factors for psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(4):915–23.

Lindberg I, Lilja M, Geale K, et al. Incidence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with skin psoriasis and associated risk factors: a retrospective population-based cohort study in Swedish routine clinical care. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(18):adv00324.

Gisondi P, Tinazzi I, El-Dalati G, et al. Lower limb enthesopathy in patients with psoriasis without clinical signs of arthropathy: a hospital-based case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(1):26–30.

Zabotti A, McGonagle DG, Giovannini I, et al. Transition phase towards psoriatic arthritis: clinical and ultrasonographic characterisation of psoriatic arthralgia. RMD Open. 2019;5(2): e001067.

Simon D, Tascilar K, Kleyer A, et al. Association of structural entheseal lesions with an increased risk of progression from psoriasis to psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022;74(2):253–62.

Tinazzi I, McGonagle D, Biasi D, et al. Preliminary evidence that subclinical enthesopathy may predict psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:2691–2.

Zabotti A, De Lucia O, Sakellariou G, et al. Predictors, risk factors, and incidence rates of psoriatic arthritis development in psoriasis patients: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Ther. 2021;8(4):1519–34.

Karmacharya P, Crowson CS, Bekele D, et al. The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis over five decades: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(10):1878–85.

Deike M, Brinks R, Meller S, Schneider M, Sewerin P. Risk of psoriatic arthritis depending on age: analysis of data from 65 million people on statutory insurance in Germany. RMD Open. 2021;7(3): e001975.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Samantha O’Dwyer, PhD, and Charli Dominguez, PhD, CMPP, of Health Interactions, Inc, and was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. This manuscript was developed in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines. The authors had full control of the content and made the final decision on all aspects of this publication.

Funding

This study and the rapid service fee were sponsored by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Joseph F. Merola, Dhaval Patil, Antton Egana, Andrea Steffens, Noah S. Webb, and Alice B. Gottlieb meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, were involved in conceptualization of the study and preparing/critically reviewing all drafts of the manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Joseph F. Merola is a consultant and/or investigator for Amgen, Arcutis, Bristol Myers Squibb, AbbVie, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Janssen, UCB, Sanofi, Regeneron, Sun Pharma, Biogen, Pfizer, and LEO Pharma. Dhaval Patil and Antton Egana are employees of Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Andrea Steffens and Noah S. Webb are employees of Optum. Alice B. Gottlieb has received honoraria as an advisory board member and consultant for Amgen, AnaptysBio, Avotres Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Dice Therapeutics, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Sanofi, UCB, and Xbiotech, and has received research/educational grants from AnaptysBio, MoonLake Immunotherapeutics AG, Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, and UCB Pharma (all paid to Mount Sinai School of Medicine).

Ethical Approval

Because the current study used only deidentified patient records and did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, institutional review board approval was not required to conduct this study. This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Merola, J.F., Patil, D., Egana, A. et al. Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Symptoms in Patients with Psoriasis and Predictors Associated with the Development of Psoriatic Arthritis: Retrospective Analysis of a US Claims Database. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 13, 2635–2648 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-01025-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-01025-8