Abstract

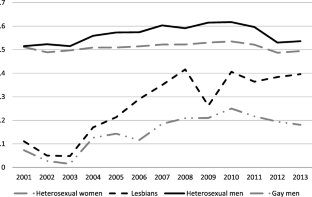

I provide evidence on the direct effects of legal same-sex marriage in the United States by studying Massachusetts, the first state to legalize it in 2004 by court order. Using confidential Massachusetts data from 2001–2013, I show that the ruling significantly increased marriage among lesbians, bisexual women, and gay men compared with the associated change for heterosexuals. I find no significant effects on coupling. Marriage take-up effects are larger for lesbians than for bisexual women or gay men and are larger for households with children than for households without children. Consistent with prior work in the United States and Europe, I find no reductions in heterosexual marriage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The data sets analyzed for the current study are not publicly available, but researchers can contact the author for information on how to apply for access. Permission must be obtained by the Massachusetts Department of Health.

Notes

Throughout, I use the term “sexual minorities” to refer to people with a gay, lesbian, or bisexual orientation or identity. Sexual orientation is a multi-faceted measure that encompasses aspects of sexual attraction, sexual behavior, and sexual identity (i.e., how one sees one’s self). For a discussion of these issues, see Laumann et al. (1994). A growing number of surveys ask respondents about one or more of these dimensions; the data I use below come from a survey that asks adults about sexual orientation.

See Badgett (2011) for qualitative evidence on the effects of access to legal same-sex marriage in Massachusetts and the Netherlands on social inclusion. Kolk and Andersson (2020) examine the effects of legal same-sex registered domestic partnership and legal same-sex marriage on union formation in Sweden using administrative data; they find that the country’s 2009 same-sex marriage policy had little effect on the rate of same-sex union formation.

Most prior demographic research on sexual minorities has relied on data that permit identification of same-sex couples in survey or administrative data (see, e.g., Alden et al. 2015; Andersson et al. 2006; Black et al. 2000; Jepsen and Jepsen 2002). The data sets used in these studies can generally not identify single sexual minorities, however, so they are unable to address union formation directly.

Badgett (2009) also studies the experience of the Netherlands through a series of qualitative interviews and also finds that gay marriage in that country did not have negative effects on different-sex marriage.

Ramos et al. (2009) also study the Massachusetts reform using data from an online survey sent to people on the mailing list of MassEquality, the state’s largest LGBT equality advocacy group. That study had a low response rate (4.2%) but found that most people in same-sex marriages were women (61%), which also matches the administrative records and my findings below.

To clarify, the national BRFSS core questionnaire does not currently include a question about sexual orientation. Moreover, no other BRFSS-based state surveys included questions about sexual orientation prior to Goodridge, so I cannot compare outcomes over time between Massachusetts and other states. This necessitates my use of a within-state control group (heterosexuals).

If the respondent were female, the word “gay” was replaced with “lesbian.” Other responses that were coded (but not offered as part of the question) were “don’t know/not sure” and “refused.” The main findings on marriage are not sensitive to how I treat individuals choosing these categories (i.e., I can exclude them, dummy them out separately, and/or make extreme assumptions such as assuming they are all gay or lesbian). The placement of the question changed between 2001 and 2002. In 2001 the sexual orientation question was asked at the end of a module on sexual behavior and sex practices. In 2002, the sexual orientation question was moved to the demographics section of the survey (after questions about education and income) where it has remained since.

Results from alternative estimation approaches returned similar results.

The MA-BRFSS provides sampling weights but changed its weighting scheme beginning in 2011 such that the weights are not comparable with the 2001–2010 data (Massachusetts Department of Health 2013). Models using the weights for 2001–2010 produced very similar results (Massachusetts Department of Health 2013).

This is notable given the long-run decline in marriage nationally (Stevenson and Wolfers 2007).

Figure A3 in the online appendix shows a small but noticeable increase in the likelihood that bisexual women report being married after 2004. Samples of bisexual men are extremely small overall and in any individual year; there is no discernable pattern for bisexual men in the figure. Notably, legal uncertainty immediately after marriage licenses were available to same-sex couples may have also led some same-sex couples to get married earlier than they otherwise would have because they feared that the anti-same-sex-marriage activism that was heightened after Goodridge put the availability of legal same-sex marriage in doubt.

Tables A1 and A2 in the online appendix provide a fuller set of coefficient estimates from estimation of Eq. (1) for women and men, respectively. Those tables show that marriage rates for heterosexual individuals exhibited a statistically insignificant increase after Goodridge. They also show that the interactions of the sexual minority indicators with the indicator for the period of legal uncertainty (i.e., DURING) are not statistically significant with the exception of the relevant interactions for bisexual men, which produce implausibly large point estimates.

Notably, however, even after the Goodridge decision, legal groups continued to encourage second parent adoptions for the non-birth parent because parental rights might not be recognized outside of Massachusetts.

Using information on household sex composition and comparing only partnered bisexual women with exactly two adults in the household, I estimate a higher rate for the Massachusetts BRFSS data (about 22% of partnered bisexual women in two-adult households have two adult women and zero adult men in them), though the qualitative pattern that partnered bisexual women are more likely to have different-sex partners remains true.

Indeed, the lesbian couple who were the plaintiffs in the Goodridge case has since separated. I did estimate Eq. (1) where the outcome was an indicator variable for being divorced, and the interaction terms of interest were not statistically significant for lesbians or gay men. The same was true when I considered an outcome for being separated. See Gates et al. (2008) for a discussion of relationship dissolution patterns of same-sex couples.

Notwithstanding Romney’s position, there were news reports that out of state same-sex couples were flocking to Massachusetts to get married (Belluck 2004b, Cooperman and Finer 2004). Provincetown, for example, actively issued marriage licenses to out-of-state same-sex couples in direct defiance of Romney’s order.

Badgett and Herman (2011) report that from July to December 2008, 37% of same-sex marriages in Massachusetts were to out of state residents, with 22% coming just from New York residents alone.

Specifically, in early years of the ACS, the U.S. Census Bureau changed a substantial share of marital status/relationship to household head responses for same-sex couple households under the (not unreasonable) assumption that two same-sex individuals could not have been legally married anywhere in the United States in the early 2000s. Writing about the 2000–2004 ACS data, Gates and Steinberger (2010) conclude: “[o]ur analyses demonstrate that same-sex couples identified in the public use ACS data suffer from a severe measurement error problem.” Although they conclude that ACS data on same-sex couples after 2005 are more reliable, this timing is problematic for the institutional features of this study since it entirely post-dates Goodridge.

Gates et al. (2008) show that civil unions in Vermont issued to out-of-state applicants fell substantially in 2004 after Massachusetts adopted same-sex marriage. Notably, civil unions to in-state applicants did not exhibit the same decline in 2004 (see their figure 7).

References

Akerlof, G. A., & Kranton, R. E. (2000). Economics and identity. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115, 715–753.

Alden, L., Edlund, L., Hammarstedt, M., & Mueller-Smith, M. (2015). Effect of registered partnership on labor earnings and fertility for same-sex couples: Evidence from Swedish register data. Demography, 52, 1243–1268.

Alm, J., & Whittington, L. A. (1999). For love or money? The impact of income taxes on marriage. Economica, 66, 297–316.

Andersson, G., Noack, T., Sierstad, A., & Weedon-Fekjaer, H. (2006). The demographics of same-sex marriages in Norway and Sweden. Demography, 43, 79–98.

Associated Press. (2008, July 31). Massachusetts Gov. Patrick signs bill allowing gay marriage by non-residents. Fox News. Retrieved from https://www.foxnews.com/story/massachusetts-gov-patrick-signs-bill-allowing-gay-marriage-by-non-residents

Badgett, M. V. L. (2009). When gay people get married: What happens when societies legalize same-sex marriage. New York: NYU Press.

Badgett, M. V. L. (2010). The economic value of marriage for same-sex couples. Drake Law Review, 58, 1081–1116.

Badgett, M. V. L. (2011). Social inclusion and the value of marriage equality in Massachusetts and the Netherlands. Journal of Social Issues, 67, 316–334.

Badgett, M. V. L., & Herman, J. L. (2011). Patterns of relationship recognition by same-sex couples in the United States. In A. K. Baumle (Ed.), International handbook on the demography of sexuality (pp. 331–362). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

Becker, G. S. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part I. Journal of Political Economy, 81, 813–846.

Becker, G. S. (1974). A theory of marriage, Part II. Journal of Political Economy, 82, S11–S26.

Belluck, P. (2004a, April 25). Romney won’t let gay outsiders wed in Massachusetts. The New York Times, p. 1A.

Belluck, P. (2004b, May 14). Gays elsewhere eye marriage Massachusetts style. The New York Times, p. 16A.

Black, D., Gates, G., Sanders, S., & Taylor, L. (2000). Demographics of the gay and lesbian population in the United States: Evidence from available systematic data sources. Demography, 37, 139–154.

Blank, R. M., Charles, K. K., & Sallee, J. M. (2009). A cautionary tale about the use of administrative data: Evidence on age of marriage laws. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(2), 128–149.

Boertien, D., & Vignoli, D. (2019). Legalizing same-sex marriage matters for the subjective well-being of individuals in same-sex unions. Demography, 56, 2109–2121.

Bonauto, M. L. (2005). Goodridge in context. Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, 40, 1–69.

Buchmueller, T. C., & Carpenter, C. S. (2012). The effect of requiring private employers to extend health benefit eligibility to same-sex partners of employees: Evidence from California. Journal of Policy Analysis & Management, 31, 388–403.

Buckles, K., Guldi, M., & Price, J. (2011). Changing the price of marriage: Evidence from blood test requirements. Journal of Human Resources, 46, 539–567.

Carpenter, C., & Gates, G. J. (2008). Gay and lesbian partnership: New evidence from California. Demography, 45, 573–590.

Carpenter, C. S. (2005). Self-reported sexual orientation and earnings: Evidence from California. ILR Review, 58, 258–273.

Carpenter, C. S., Eppink, S. T., Gonzales, G., & McKay, T. (2019). Effects of access to legal same-sex marriage on marriage and health: Evidence from BRFSS (NBER Working Paper No. 24651). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Cherlin, A. J. (2004). The deinstitutionalization of American marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 848–861.

Cooperman, A., & Finer, J. (2004, May 18). Gay couples marry in Massachusetts: Hundreds tie knot on day one, but questions remain. Washington Post, p. A1.

Dee, T. S. (2008). Forsaking all others? The effects of ‘gay marriage’ on risky sex. Economic Journal, 118, 1055–1078.

Dillender, M. (2014). The death of marriage? The effects of new forms of legal recognition on marriage rates in the United States. Demography, 51, 563–585.

Dutton, S., De Pinto, J., Salvanto, A., & Backus, F. (2013). Poll: 53% of Americans support same-sex marriage (CBS News poll analysis). Retrieved from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/poll-53-of-americans-support-same-sex-marriage/

Francis, A. M., Mialon, H. M., & Peng, H. (2012) In sickness and in health: Same-sex marriage laws and sexually transmitted infections. Social Science & Medicine, 75, 1329–1341.

Friedberg, L. (1998). Did unilateral divorce raise divorce rates? Evidence from panel data. American Economic Review, 88, 608–627.

Fryer, R. G., Jr. (2007). Guess who’s been coming to dinner? Trends in interracial marriage over the 20th century. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(2), 71–90.

Gates, G. J., Badgett, M. V. L., & Ho, D. (2008). Marriage, registration, and dissolution by same-sex couples in the United States (Williams Institute report). Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5tg8147x

Gates, G. J., & Steinberger, M. D (2010). Same-sex unmarried partner couples in the American Community Survey: The role of misreporting, miscoding and misallocation (Working paper). Retrieved from http://economics-files.pomona.edu/steinberger/research/Gates_Steinberger_ACS_Miscode_May2010.pdf

Gevrek, D. (2014). Interracial marriage, migration and loving. Review of Black Political Economy, 41, 25–60.

Gonzales, G. (2015). Association of the New York State Marriage Equality Act with changes in health insurance coverage. JAMA, 314, 727–728.

Goodridge v. Department of Public Health, 440 Mass. 309, 798 N. E. 2d 941 (Mass. 2003). Retrieved from http://masscases.com/cases/sjc/440/440mass309.html

Hansen, M. E., Martell, M. E., & Roncolato, L. (2020). A labor of love: The impact of same-sex marriage on labor supply. Review of Economics of the Household, 18, 265–283.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., O’Cleirigh, C., Grasso, C., Mayer, K., Safren, S., & Bradford, J. (2012). Effect of same-sex marriage laws on health care use and expenditures in sexual minority men: A quasi-natural experiment. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 285–291.

Herek, G. (2000). The psychology of sexual prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9, 19–22.

Ihrke, D. K., & Farber, C. S. (2012). Geographical mobility: 2005 to 2010 (Current Population Reports, No. P20-567). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Jepsen, C., & Jepsen, L. K. (2015). Labor market specialization within same-sex and different-sex couples. Industrial Relations, 54, 109–130.

Jepsen, L. K., & Jepsen, C. A. (2002). An empirical analysis of the matching patterns of same-sex and opposite-sex couples. Demography, 39, 435–453.

Kolk, M., & Andersson, G. (2020). Two decades of same-sex marriage in Sweden: A demographic account of developments in marriage, childbearing, and divorce. Demography, 57, 147–169.

Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J., H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels S. (1994). The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Manning, W. D., Brown, S. L., & Stykes, J. B. (2016). Same-sex and different-sex cohabiting couple relationship stability. Demography, 53, 937–953.

Massachusetts Department of Public Health. (2013). MA BRFSS methodology (Technical report). Retrieved from http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/dph/behavioral-risk/methodology.pdf

McCarthy, J. (2019, May 22). U.S. support for gay marriage stable, at 63%. Gallup News. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/257705/support-gay-marriage-stable.aspx

Meyer, I. H. (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36, 38–56.

Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. (2015). Retrieved from https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/14pdf/14-556_3204.pdf

Parker, K. (2015). Among LGBT Americans, bisexuals stand out when it comes to identity, acceptance (Pew Research Center Fact Tank report). Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/02/20/among-lgbt-americans-bisexuals-stand-out-when-it-comes-to-identity-acceptance/

Peters, H. E. (1986). Marriage and divorce: Informational constraints and private contracting. American Economic Review, 76, 437–454.

Pew Research Center. (2012). More support for gun rights, gay marriage than in 2008 or 2004 (U.S. Politics & Policy report). Retrieved from http://www.people-press.org/2012/04/25/more-support-for-gun-rights-gay-marriage-than-in-2008-or-2004/?src=prc-headline

Pew Research Center. (2013). Growing support for gay marriage: Changed minds and changing demographics (U.S. Politics & Policy report). Retrieved from https://www.people-press.org/2013/03/20/growing-support-for-gay-marriage-changed-minds-and-changing-demographics/

Raifman, J., Moscoe, E., Austin, S. B., & McConnell, M. (2017) Difference-in-differences analysis of the association between state same-sex marriage policies and adolescent suicide attempts. JAMA Pediatrics, 171, 350–356.

Ramos, C., Goldberg, N. G., & Badgett, M. V. L. (2009). The effects of marriage equality in Massachusetts: A survey of the experiences and impact of marriage on same-sex couples (Williams Institute report). Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9dx6v3kj

Rauch, J. (2004). Gay marriage: Why it is good for gays, good for straights, and good for America. New York, NY: Times Books.

Sansone, D. (2019). Pink work: Same-sex marriage, employment, and discrimination. Journal of Public Economics, 180, 104086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2019.104086

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2007). Marriage and divorce: Changes and their driving forces. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(2), 27–52.

Trandafir, M. (2014). The effect of same-sex marriage laws on different-sex marriage: Evidence from the Netherlands. Demography, 51, 317–340.

Trandafir, M. (2015). Legal recognition of same-sex couples and family formation. Demography, 52, 113–151.

United States v. Windsor. 570 U.S. 744 (2013). Retrieved from https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/12pdf/12-307_6j37.pdf

Wolfers, J. (2006). Did unilateral divorce laws raise divorce rates? A reconciliation and new results. American Economic Review, 96, 1802–1820.

Acknowledgments

I thank Lee Badgett, Marianne Bitler, Patrick Button, Jeff Frank, Gilbert Gonzales, Helen Hawk, Bill Jesdale, Marieka Klawitter, Stewart Landers, Trevon Logan, Hai Nguyen, Liz Peters, Manisha Shah, Mark Stehr, and seminar participants at the U.S. Census Bureau, Johns Hopkins University, The Ohio State University, UC Santa Barbara, University of California Irvine, University of Illinois-Chicago, University of New Hampshire, University of Southern California, Vanderbilt, and the 2012 APPAM meetings for very useful comments and discussions. The data used in this paper are protected by a confidentiality agreement; researchers interested in the data can contact the author for information on how to obtain access. I thank Helen Hawk, Maria McKenna, and Liane Tinsley for help with the Massachusetts BRFSS data. The contents of this paper do not reflect the views of the Massachusetts Department of Health or any other organization. All errors and omissions are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics and Consent

The author confirms that guidelines from the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) were followed for this study.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 361 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carpenter, C.S. The Direct Effects of Legal Same-Sex Marriage in the United States: Evidence From Massachusetts. Demography 57, 1787–1808 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00908-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00908-1