Abstract

This study finds heterogeneous effects of teen childbearing on education and labor market outcomes across socioeconomic status and race. Using miscarriages to put bounds on the causal effects of teen childbearing, results show that teen childbearing leads to lower educational attainment, lower income, and greater use of welfare for individuals who come from counties with better socioeconomic conditions. However, there are no significant adverse effects for individuals who come from counties with worse socioeconomic conditions. Across race, teen childbearing leads to negative consequences for white teens but no significant negative effects for black or Hispanic and Latino teens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Among the population analyzed herein, 14 % of white women, 28 % of black women, and 23 % of Hispanic or Latino women in the sample reported teen births. Among those who reported teen births, approximately 68 % come from families at or below the median reported income.

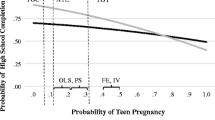

In addition, Hotz et al. (1997) showed that even when a proportion of miscarriages is assumed to be nonrandom, the estimated bounds reach similar conclusions to those from studies assuming that all miscarriages are random.

Lang and Nuevo-Chiquero (2012) also showed that reported miscarriages may be drawn from a more advantaged population because advantaged types are more aware when an early pregnancy has taken place. This would diminish the upward bias of IV estimates and increase the downward bias on the OLS estimates.

See Kane et al. (2013) for a detailed discussion of the limits of propensity score matching in the context of estimating the effects of teen childbearing.

Other work defined teen pregnancy as pregnancies that begin by age 18 (Ashcraft and Lang 2006; Ashcraft et al. 2013; Hoffman and Maynard 2008; Hotz et al. 2005). Because Add Health reports only end dates, I use pregnancies that end by the age of 18 years and 9 months. This is the same way that Fletcher and Wolfe (2009) defined teen pregnancy using Add Health data. The pattern of results is robust to extending the sample to include pregnancies that end prior to age 20.

The Wave 4 sample is bigger because of a higher response rate during this wave as well as a larger number of reported teen pregnancies.

Labor income is reported earnings from wages, salaries, tips, bonuses, overtime, and self-employment. If earnings were unknown, respondents were asked to select a range of income that represented their best guess. The middle of these ranges and the bottom of the top range are used in these cases.

Respondents selected a range of values for household income and reported assets. The midpoint of these ranges or the bottom of the top range is used for the values of these variables.

Using certain drugs has also been linked to miscarriages, but this variable is not available for Wave 4. The Wave 3 results are not sensitive to excluding the control for drug use.

Wave 1 also provides contextual variables, but these come from the 1990 census and reflect conditions in 1989, prior to most pregnancies and less relevant to the time during which women are making schooling and labor market decisions. However, the results are similar when socioeconomic status is defined based on these earlier contextual variables instead of the Wave 3 variables.

Results using other socioeconomic divisions can be provided upon request.

Results are similar if the whole sample is used to define the median level instead of just the pregnant teen sample.

Categories are defined as Hispanic or Latino; black with no report of Hispanic or Latino; and white with no report of black, Hispanic, or Latino. Results are robust to using categories as reported by the interviewer as well.

This result is obtained by running the low-income and high-income observations in one regression and testing the significance of the interaction terms.

When results are broken into quartiles of income, similar results hold. Even though the consequences of teen childbearing generally worsen as socioeconomic status improves, in some cases, the effects are not strictly monotonic across quartile. For instance, teens from the highest quartile of income experience less detrimental effects than those from the next highest quartile.

One may worry that the sample of women differs between waves and could drive this effect. However, the same pattern is true even when the sample is limited to observations that appear in both waves of the data.

The F test is obtained by estimating the results in one regression, allowing interactions with race and Hispanic and Latino origin, and testing whether the interactions are both 0. In pairwise t tests, the coefficients for the Hispanic and Latino group are significantly different from the coefficients for the white group, with p values of .032 and .054 for the lower and upper bounds, respectively. The lower bound for the black group is significantly different from the lower bound for the white group, with a p value of .093. The differences between the black and Hispanic and Latino group are not significantly different at conventional levels.

The estimates on high school diploma receipt and earnings for Hispanic and Latino teens are significantly different from the estimates for white or black teens at the 5 % level or less, and the estimates on years of schooling for Hispanic and Latino teens are significantly different from the estimates for white teens at the 5 % level. The other individual estimates are not significantly different across race at conventional levels.

The increase in GED receipt is significantly different from the coefficient for white teens, with p values of .059 and .027 for the lower and upper bounds, respectively.

The increase in assets is significantly different from the coefficient on assets for white teens, with p values of .055 and .035 for the lower and upper bounds, respectively.

References

Anderson, M. L. (2008). Multiple inference and gender differences in the effects of early intervention: A reevaluation of the Abecedarian, Perry Preschool, and Early Training projects. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 103, 1481–1495.

Ashcraft, A., Fernandez-Val, I., & Lang, K. (2013). The consequences of teenage childbearing: Consistent estimates when abortion makes miscarriage non-random. Economic Journal, 123, 875–905.

Ashcraft, A., & Lang, K. (2006). The consequences of teenage childbearing (NBER Working Paper No. 12485). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Card, J. J., & Wise, L. L. (1978). Teenage mothers and teenage fathers: The impact of early childbearing on the parents’ personal and professional lives. Family Planning Perspectives, 10, 199–205. https://doi.org/10.2307/2134267

Diaz, C. J., & Fiel, J. E. (2016). The effect(s) of teen pregnancy: Reconciling theory, methods, and findings. Demography, 53, 85–116.

Edin, K., & Kefalas, M. (2005). Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Fletcher, J. M., & Wolfe, B. L. (2009). Education and labor market consequences of teenage childbearing: Evidence using the timing of pregnancy outcomes and community fixed effects. Journal of Human Resources, 44, 303–325.

Furstenberg, F. F., Jr. (1976). The social consequences of teenage parenthood. Family Planning Perspectives, 8, 148–164. https://doi.org/10.2307/2134201

Geronimus, A. T., & Korenman, S. (1992). The socioeconomic consequences of teen childbearing reconsidered. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107, 1187–1214.

Harris, K. M. (2009). The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (AddHealth), Waves I & II, 1994–1996; Wave III, 2001–2002; Wave IV, 2007–2009 [Machine-readable data file and documentation]. Chapel Hill: Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Harris, K. M., Halpern, C. T., Whitsel, E., Hussey, J., Tabor, J., Entzel, P., & Udry, J. R. (2009). The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research design. Retrieved from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design

Hoffman, S. D., Foster, E. M., & Furstenberg, F. F., Jr. (1993). Reevaluating the costs of teenage childbearing. Demography, 30, 1–13.

Hoffman, S. D., & Maynard, R. A. (Eds.). (2008). Kids having kids: Economic costs and social consequences of teen pregnancy (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

Hotz, V. J., McElroy, S. W., & Sanders, S. G. (2005). Teenage childbearing and its life cycle consequences: Exploiting a natural experiment. Journal of Human Resources, 40, 683–715.

Hotz, V. J., Mullin, C. H., & Sanders, S. G. (1997). Bounding causal effects using data from a contaminated natural experiment: Analyzing the effects of teenage childbearing. Review of Economic Studies, 64, 575–603.

Hoynes, H., Schanzenbach, D. W., & Almond, D. (2016). Long-run impacts of childhood access to the safety net. American Economic Review, 106, 903–934.

Kane, J. B., Morgan, S. P., Harris, K. M., & Guilkey, D. K. (2013). The educational consequences of teen childbearing. Demography, 50, 2129–2150.

Kearney, M. S., & Levine, P. B. (2012). Why is the teen birth rate in the United States so high and why does it matter? Journal of Economics Perspectives, 26(2), 141–166.

Kearney, M. S., & Levine, P. B. (2014). Income inequality and early nonmarital childbearing. Journal of Human Resources, 49, 1–31.

Kling, J. R., Liebman, J. B., & Katz, L. F. (2007). Experimental analysis of neighborhood effects. Econometrica, 75, 83–119.

Lang, K., & Nuevo-Chiquero, A. (2012). Trends in self-reported spontaneous abortions: 1970–2000. Demography, 49, 989–1009.

Lang, K., & Weinstein, R. (2015). The consequences of teenage childbearing before Roe v. Wade. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(4), 169–197.

Levine, D. I., & Painter, G. (2003). The schooling costs of teenage out-of-wedlock childbearing: Analysis with a within-school propensity-score-matching estimator. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85, 884–900.

Ribar, D. C. (1994). Teenage fertility and high school completion. Review of Economics and Statistics, 76, 413–424.

Sedgh, G., Finer, L. B., Bankole, A., Eilers, M. A., & Singh, S. (2015). Adolescent pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates across countries: Levels and recent trends. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56, 223–230.

Waite, L. J., & Moore, K. A. (1978). The impact of an early first birth on young women’s educational attainment. Social Forces, 56, 845–865.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for helpful feedback from Briggs Depew, Art Goldsmith, Lars Hansen, Michael Makowsky, Jennifer Trudeau, Andy Zuppann, participants at the AEA and SEA annual meetings and the IZA World Labor Conference, and anonymous referees. All mistakes remain my own. This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by Grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from Grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 92 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gorry, D. Heterogeneous Consequences of Teenage Childbearing. Demography 56, 2147–2168 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00830-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00830-1