Abstract

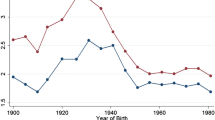

Very few studies have examined the effect of religiosity on fertility at the macro level. This note extends these studies by using a larger data set and more advanced econometric techniques. In addition, this note estimates the macro-level effect of religiosity on fertility both for a total sample of 25 Christian countries between 1925 and 2000 and for three subsamples: Catholic, Protestant, and mixed Catholic-Protestant countries. Results show that religiosity, in general, has a positive long-run effect on fertility. However, this effect is not significant for Catholic countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The existence of such peer effects implies that nonreligious people in more religious societies may have more children than nonreligious people in less religious societies, whereas religious people in less religious societies may have fewer children than religious people in more religious societies.

The most plausible explanation for this is that the doctrine of the Catholic Church is pronatalist, whereas in Protestant religions, fertility is generally considered a matter of individual choice (e.g., Lehrer 1996).

In the absence of panel cointegration, conventional panel regressions involving nonstationary variables are spurious, often producing statistics that suggest significant relationships, when in fact none exist (e.g., Kao 1999).

The panel DOLS estimator corrects for endogeneity and serial correlation by including lead, lag, and current values of the differenced regressors in the regression.

Alternatively, the magnitude of the estimated effect can be evaluated by multiplying the DOLS coefficient on RELit by the average change in the church attendance rate and dividing it by the average change in the birth rate. The resulting value is 0.222, implying that declining religiosity has been responsible for about 22.2 % of the fertility decline between 1925 and 2000.

The online appendix presents a sensitivity analysis demonstrating that the positive (average) religiosity-fertility coefficient is robust to the use of alternative estimation techniques, the inclusion of additional variables, the use of an alternative measure of fertility, and to splitting the sample period into two equal periods (1925–1960 and 1965–2000).

A precise definition of the subsamples is given in the online appendix.

This group is relatively heterogeneous, consisting of two Eastern Orthodox countries (Bulgaria and Cyprus), one Anglican country (Great Britain), and two countries whose majority population is a mix of Catholics, Protestants, and Anglicans (Australia and New Zealand). Therefore, the effect of religiosity on fertility may well differ across these subgroups. Unfortunately, the number of countries in these subgroups is too small to further subdivide the group of non-Catholic, non-Protestant Christian countries. Note that the Anglican Communion considers itself to be both Catholic and Protestant. Following the classification of the World Religion Dataset (available at http://www.correlatesofwar.org/data-sets/world-religion-data), I therefore do not classify Anglicans as Protestants, as some studies have done, but I distinguish between Anglicans and Protestants.

References

Berman, E., Iannaccone, L. R., & Ragusa, G. (2018). From empty pews to empty cradles: Fertility decline among European Catholics. Journal of Demographic Economics, 84, 149–187.

Engle, R. E., & Granger, C. W. J. (1987). Cointegration and error-correction: Representation, estimation, and testing. Econometrica, 55, 251–276.

Feyrer, J., Sacerdote, B., & Stern, A. D. (2008). Will the stork return to Europe and Japan? Understanding fertility within developed nations. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(3), 3–22.

Frejka, T., & Westoff, C. F. (2008). Religion, religiousness and fertility in the U.S. and in Europe. European Journal of Population, 24, 5–31.

Goldscheider, C., & Uhlenberg, P. R. (1969). Group status and fertility. American Journal of Sociology, 74, 361–372.

Guetto, R., Luijkx, R., & Scherer, S. (2015). Religiosity, gender attitudes and women’s labour market participation and fertility decisions in Europe. Acta Sociologica, 58, 155–172.

Hayford, S. R., & Morgan, S. P. (2008). Religiosity and fertility in the United States: The role of fertility intentions. Social Forces, 86, 1163–1188.

Iannaccone, L. (2003). Looking backward: A cross-national study of religious trends. Fairfax, VA: George Mason University.

ISSP Research Group. (2018). International Social Survey Programme: Religion III—ISSP 2008 [Data file version 2.3.0]. Cologne, Germany: GESIS Data Archive. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13161

Kao, C. (1999). Spurious regression and residual-based tests for cointegration in panel data. Journal of Econometrics, 90, 1–44.

Kao, C., & Chiang, M.-H. (2000). On the estimation and inference of a cointegrated regression in panel data. In B. H. Baltagi, T. B. Fomby, & R. C. Hill (Eds.), Advances in econometrics: Nonstationary panels, panel cointegration, and dynamic panels (Vol. 15, pp. 179–222). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Lehrer, E. L. (1996). Religion as a determinant of marital fertility. Journal of Population Economics, 9, 173–196.

McGregor, P., & McKee, P. (2016). Religion and fertility in contemporary Northern Ireland. European Journal of Population, 32, 599–622.

Mitchell, B. R. (2007). International historical statistics. 1750–2005: Europe; Americas; Africa, Asia and Oceania (Vols. 1, 2, 3). Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mosher, W. D., & Hendershot, G. E. (1984). Religion and fertility: A replication. Demography, 21, 185–191.

Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2004). Sacred and secular: Religion and politics worldwide. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Pesaran, M. H. (2004). General diagnostic tests for cross section dependence in panels (CESifo Working Paper Series No. 1229). Munich, Germany: CESifo Group.

Acknowledgments

I thank four anonymous referees for their comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 518 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Herzer, D. A Note on the Effect of Religiosity on Fertility. Demography 56, 991–998 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00774-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00774-6