Abstract

A 100 kWth dual fluidized bed steam gasification pilot plant has been developed at TU Wien to convert different types of biogenic fuels into a valuable product gas. In this paper, the conversion of different biogenic fuels in combination with the utilization of CO2 as alternative gasification agent was investigated in the mentioned pilot plant. For this purpose, five experimental campaigns were carried out aiming at the investigation of softwood as reference fuel, and rapeseed cake, bark and lignin as alternative fuels. Pure olivine as well as a mixture (90/10 wt%) of olivine and limestone were used as bed materials. The product gas compositions of the different biogenic fuels changed depending on the elemental composition of the biogenic fuels. Thus, a high amount of carbon in the fuel enhanced CO formation, whereas an increased content of oxygen led to higher CO2 contents. Additionally, the presence of alkali metals in the biomass ash favoured the production of CO. The addition of limestone enhanced the H2 and CO contents via the water gas shift reaction as well as steam and dry reforming reactions, but had no significant effect on tar contents. Overall, this paper presents the feasibility of the dual-fluidized bed gasification process of different biogenic fuels with CO2 as gasification agent.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In November 2016, the European Union published a recast of the Renewable Energy Directive–Recast to 2030 (RED II) to strengthen the awareness of the countries regarding the mitigation of the effects of the climate change. RED II targets the renewable energy consumption in Europe up to 32% by 2030. Additionally, fuel supply companies have to replace a minimum of 14% of the energy consumed in road and rail transport by renewable energy carriers until 2030. Fuels used in the aviation and maritime sectors can contribute to the 14% transport target but are not obliged [1]. Based on early estimates carried out by Eurostat, the global CO2 emissions increased by 1.4% to 32.5 Gt in 2017 [2]. Due to the fact that CO2 emissions account for about 80% of the overall greenhouse gas emissions [3], negative values of CO2 emissions are required to mitigate the climate change effects. This was also reported by IPCC in 2014 [4]. For this purpose, the development of efficient technologies with the aim of recycling CO2 within the processes is necessary. In this way, it is possible to influence the closing of the overall carbon cycle in a positive way and reduce CO2 emissions at the same time. This idea of a closed carbon cycle with CO2 reuse within the process can be traced back to the 1970s. At that time Steinberg et al. already investigated the use of nuclear power-generated electrolytic hydrogen and oxygen to convert CO and CO2 recovered from industrial processes to synthetic methanol [5]. Nowadays, the thermochemical process “biomass gasification” could be a renewable option for realizing the idea mentioned above. Through the gasification of biomass and the recycling of produced CO2 within the process, a high-valuable product gas can be generated, which could be further upgraded to synthetic fuels. This work focuses on the dual fluidized bed (DFB) CO2/steam biomass gasification (see Fig. 1), which has a great potential in this field and is therefore a main research topic at TU Wien since many years. So far, only steam was used as gasification agent in the DFB pilot plant at TU Wien. Therefore, the use of CO2 instead of steam presents a novel possibility of reducing CO2 emissions within the DFB process and producing a CO-rich product gas. The following points make the use of CO2 as gasification agent in the DFB biomass gasification process attractive:

-

a)

The recycling and reuse of CO2 within the process.

-

b)

The decrease of CO2 emissions at the same time.

-

c)

The positive influence on the overall carbon cycle.

-

d)

No heat and water requirement, which would be needed for the generation of steam [6, 7].

Besides the opportunity to recycle CO2 within the DFB gasification process, it is also possible to convert alternative, low-grade fuels in the DFB pilot plant. In this way, the conventional biomass gasification of wood can be shifted to a sustainable gasification process and contribute to a sustainable energy engineering. By the use of alternative, low-grade fuels, the life cycle of these materials can be increased and the CO2 emissions reduced. Therefore, this research focuses on the reuse of alternative, residual materials and the conversion to high-valuable products by reusing CO2 within the process. Extensive investigations dealing with fuel variations in the DFB gasification system using steam as gasification agent were already carried out successfully at TU Wien [8,9,10]. However, the gasification of biogenic, low-grade fuels with the use of CO2/steam mixtures as gasification agent has not been investigated so far in the DFB reactor system. Therefore, investigations dealing with the influence of CO2/steam gasification of bark, rapeseed cake and lignin on the product gas (PG) composition are presented within this paper. Softwood was used as reference fuel. In Figs. 1 and 2, the DFB gasification system, which was used for the test campaigns, is shown. It consists of a gasification reactor (GR; blue rectangle) and a combustion reactor (CR; red rectangle). The two reactors are connected by loop seals (horizontal arrows). A bed material circulates between the GR and the CR across the loop seals. On the one hand, the bed material serves as a heat transport agent, which transports the produced heat by burning residual char from the CR to the GR. In this way, the endothermic gasification reactions can take place. On the other hand, it acts as a catalytically active material to enhance the ongoing chemical reactions. The GR is visually divided in (i) a lower part, where devolatilization and gasification takes place and (ii) an upper part, where gasification and reforming reactions occur. In the GR, the solid fuel and the gasification agents such as CO2 and steam are introduced. In the CR, air and optional additional fuel are introduced. The optional additional fuel compensates the heat losses in the pilot plant and enables temperature control during the experiments. The main product of the GR named product gas is composed of carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen (H2), carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), ethylene (C2H4), steam (H2O) and other minor components. The flue gas of the CR contains mainly CO2, H2O, N2 and O2. The product gas of the GR can further be used in different syntheses to produce fuels such as FT fuels [12, 13], chemicals or mixed alcohols [14].

Sketch indicating dimensions and positions of presented temperatures (left) and Barracuda snapshot with particles movement (right) [11]

Relevant chemical reactions

On the left side of Fig. 1, relevant chemical reactions during CO2/steam gasification are displayed. The heterogeneous gas-solid reactions (Eqs. 5–7) are mainly dominant in the lower gasification reactor and the homogeneous gas-gas reactions (Eqs. 1–4) mainly prevail in the upper GR. Eq. 1 displays the water gas shift (WGS) reaction, which is considered as the most essential homogeneous gas-gas reaction in gasification processes. In Eq. 2, the deviation from WGS equilibrium pδeq,WGS is presented. The equilibrium constant Kp,WGS(T) was calculated using the software tool HSC [15]. A value of zero of pδeq, WGS would mean that the equilibrium state of the WGS reaction is reached, whereas a deviation from zero implies a deviation from the equilibrium state. A negative algebraic sign indicates that the actual state is on the side of the reactants. This means that a further reaction is thermodynamically possible. However, if the algebraic sign is positive, the actual state is on the side of the products. This state can thermodynamically not be reached via the WGS reaction alone, but by, e.g., intermediate products of the devolatilization of higher hydrocarbons. Kuba et al. found out that the WGS reaction is a follow-up reaction of the steam reforming reaction, where part of the produced CO during steam reforming is converted into H2 and CO2 in the presence of H2O. [16] Eq. 3 describes the endothermic steam reforming of hydrocarbons and is especially important for steam gasification. In contrast, Eq. 4 presents the endothermic dry reforming reaction, which decomposes hydrocarbons with CO2 to CO and H2. When CO2 is used as gasification agent, a second reaction, the endothermic Boudouard (BOU) reaction, plays a crucial role. This was also stated in literature [17]. The Boudouard reaction displayed in Eq. 5 is a heterogeneous solid-gas reaction and aims the production of CO via the reaction of char from pyrolysis with CO2. In Eq. 6, the logarithmic deviation from the Boudouard (BOU) reaction pδeq, BOU is shown. The equilibrium constant Kp,BOU(T) was calculated by the use of the software tool HSC [15] as well. When pδeq, BOU is 0, the Boudouard reaction is in equilibrium. When pδeq,BOU > 0, the state of equilibrium lies on the product side, whereas when pδeq,BOU < 0, the equilibrium is located on the reactants side. The heterogeneous water gas reaction is shown in Eq. 7 and describes the production of CO and H2

The fact that there is limited or nearly no literature dealing with CO2/steam gasification of different biogenic residues makes the investigations presented in this publication unique. Most of the existing literature covers the reaction of char with CO2 and steam through thermogravimetric analyses. For example, Butterman et al. found out that the carbon conversion was complete, when a mixture of 25/75 vol% of CO2/steam was used compared to a conversion of 90% when pure steam was introduced in a temperature range of 800 – 1000 °C. They assumed that CO2 enhanced the pore structure, particularly the micropores of the residual carbon skeleton after drying and devolatilization. This facilitated the efficient CO2 gasification of the solid [6]. Huang et al., Mitsuoka et al. and Habibi et al. reported that alkali metals in the biomass ash enhanced the reactivity of char for CO2 gasification catalytically [18,19,20]. Zhang et al. also revealed that the critical factor for an improved char reactivity under mixed CO2/H2O atmosphere was the catalytic activity of alkali metals like Na [21]. Cheng et al. discovered that the CO2 amount in the gasification agent, the CO2 to biomass ratio, the size of the woodchips as well as the moisture content of the woodchips had a great impact on the gasification behaviour. The cold gas efficiency as well as the CO2 conversion rate were both decreased with increasing moisture content and particle size. [22] Another researcher, Ren et al., considered the gasification temperature as the most significant parameter which affects the gasification reactivity of char and controls the gasification rate [23]. These findings and hypothesis were used for comparison with the generated results within this publication.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 DFB CO2/steam gasification reactor system

The 100 kWth DFB biomass gasification pilot plant went into operation in 2014 [24]. The gasification reactor was designed as bubbling bed in the lower part and as counter-current column with turbulent fluidized bed zones in the upper part. In the upper part of the gasification reactor constrictions were implemented (see Fig. 2). These constrictions enabled an increased hold-up of bed material along the height of the reactor. In this way, the interaction of catalytically active hot bed material particles with the product gas could be enhanced and residence time increased [25, 26]. At the same time, the high temperatures in the counter-current column had a positive effect on tar destruction [27]. Figure 3 displays the upper part of the DFB gasification pilot plant with two fuel hoppers. In Fig. 4, the lower part of the pilot plant with the fuel feeding screw and the ash removal containers is shown. Coarse ash, which accrues during test runs, can be withdrawn in the lower part of the system. The removal of coarse ash is particularly important, when ash-rich fuels are used for gasification [29]. More information about the DFB gasification system can be found in [24, 30].

Upper part of the 100 kWth gasification pilot plant, TU Wien [28]

Lower part of the 100 kWth gasification pilot plant, TU Wien [28]

2.2 Online measurement setup

During the test campaigns, the pilot plant was controlled by a programmable logic controller (PLC). In this way, a continuous measurement and recoding of all relevant flow rates, temperatures, pressures and main gas components like H2, CO, CO2 and CH4 was possible. For the online measurement of the main gas components, a Rosemount NGA2000 measurement device was used. Ethylene (C2H4), ethane (C2H6), propane (C3H8) and nitrogen (N2) were measured via a gas chromatograph (Perkin Elmer ARNEL–Clarus 500) every 12 – 15 min. Before to the online measurement, the product gas had to be cleaned to protect the devices from contaminants. Therefore, a glass wool filter and washing bottles filled with rapeseed methyl ester (RME) were used to eliminate condensable components like water and tar. A more detailed description of the measurement setup can be found in [10, 31].

2.3 Offline measurement setup

Tar, char and dust were measured isokinetically with impinger bottles to condense and dissolve hydrocarbons following the suggested procedure of the tar protocol [32]. Toluene was used as solvent in the impinger bottles. Thus, the simultaneous measurement of water was possible. Determined tar contents were divided into gravimetric tar and GC/MS tar. The measurement and analysis procedure is described in more detail in [33, 34]. All tar contents are presented without benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene (BTEX). The amount of solid particles like char and dust were analysed by using a small cyclone with a quartz wool stuffed filter cartridge.

2.4 Investigated materials

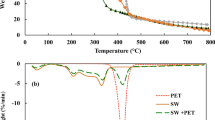

The proximate and ultimate analyses as well as the main components of the biomass ashes of the investigated fuels softwood (SW), bark (BA), rapeseed cake (RSC) and straw-derived lignin (SLI) are given in Table 1. Bark originated from oak. It was found out that the ash of softwood and bark were very rich in calcium (Ca), the ash of rapeseed cake included a high content of phosphorus (P) and the ash of lignin contained a high amount of sodium (Na). Additionally, four characteristic ash fusion temperatures, namely deformation (A), spherical (B), hemi-spherical (C) and flow (D) temperature are presented. These ash fusion temperatures are dependent on the composition of the ash. A further opportunity to predict the ash melting behaviour of biomass ashes is presented by the ternary diagram shown in Fig. 5. This ternary diagram presented by Vassilev et al. [35] predicts the initial ash deformation temperature (DT), which equals temperature A of Table 1. The areas of the DTs were established by Vassilev et al. based on 55 varieties of biomasses and are dependent on the chemical composition of the biomass ashes. In this ternary diagram, the DTs of the investigated fuels SW, BA, RSC and SLI were marked as well. It can be seen that the findings of Fig. 5 correspond to the results displayed in Table 1. However, the DT of bark is located outside of the proposed areas, but situated on the left side of the grey area (DT, 1100 – 1300 °C), which fits to the results of the ash analysis.

Areas of initial ash deformation temperatures (DT) of investigated fuels based on investigations of Vassilev et al. [35]; SW softwood; BA bark; SLI straw-derived lignin; RSC rapeseed cake;

Olivine (oilv.) as well as mixtures of olivine and limestone (lime.) were used as bed materials in the presented test campaigns. Olivine was used because it is known as state-of-the-art bed material and typically used in industrial-sized gasification plants [36]. It exhibits a moderate catalytic activity and quite good attrition resistance [37]. Limestone was used due to its advantageous catalytic properties, which was also reported by Pfeifer et al. [38]. It was filled into the pilot plant as calcium carbonate (CaCO3). There, CaCO3 was converted to the catalytically active form calcium oxide (CaO) due to the high temperatures in the reactor system [39]. CaO showed high catalytic activity, which was advantageous for the ongoing gasification reaction. The composition of olivine and limestone is shown in Table 2. Pictures of the investigated fuel pellets are shown in Fig. 6.

2.5 Validation of process data with IPSEpro

All measured data of the presented test campaigns were validated with the software simulation tool IPSEpro. IPSEpro was applied to calculate mass and energy balances by using a detailed model library, which was developed at TU Wien over many years. In this way, the results can be presented in a highly valuable and representative form. The following key figures were selected to describe the CO2/steam gasification test campaigns: The steam to fuel ratio φSF is shown in Eq. 8. It describes the mass of steam as gasification agent and the mass of water in the fuel related to the mass of dry and ash-free fuel. Due to the use of steam as gasification agent to convert carbonic feedstock and to have the possibility to compare biomass gasification investigations in literature, the steam to carbon ratio φSC was introduced (Eq. 9). The steam-related water conversion XH2O is defined as the water consumed for, e.g., CO and H2 production in relation to the sum of water, which is fed to the GR as gasification agent and fuel water (see Eq. 10). Furthermore, a fuel-related water conversion XH2O,fuel is introduced. It expresses the amount of water consumed per mass unit of converted fuel during gasification (Eq. 11). In Eq. 12, the cold gas efficiency ηCG, is displayed, which is defined as the chemical energy content of gaseous components in the tar- and char-free product gas related to the chemical energy in the fuel. All values are based on the lower heating value (LHV). The overall cold gas efficiency ηCG,o is presented in Eq. 13. It describes the amount of chemical energy in the product gas in relation to the fuel introduced into the gasification and combustion reactor minus appearing heat losses. The product gas yield PGY describes the ratio between dry product gas to dry and ash-free fuel, which is introduced into the GR (see Eq. 14). [40, 41]

The CO2 conversion ratio was introduced as a new key figure due to the use of CO2 as gasification agent. The CO2 conversion XCO2 displayed in Eq. 15 gives the ratio of consumed CO2 in the product gas to the amount of introduced CO2 into the GR. Additionally, the fuel-related CO2 conversion, XCO2,fuel is introduced (Eq. 16), which is the amount of CO2 consumed per mass unit of converted fuel during gasification. For XCO2 and XCO2,fuel, the amount of CO2, which can be produced from carbon in the fuel is calculated based on investigations by Neves et al. [42]. For this purpose, the yield of gas, which can be produced via pyrolysis was multiplied with the yield of CO2 produced in the pyrolysis gas. Both yields are dependent on temperature. For simplification, the factor kCO2 was introduced. It describes the above mentioned conversion of C of dry and ash-free fuel to CO2. The temperature dependency of kCO2 is displayed in Fig. 7. For the calculation of the factor kCO2, the “T GRlowera” (see Table 3) was used. The CO2 to fuel ratio φCO2F describes the ratio of introduced CO2 as gasification agent to dry and ash-free fuel introduced into the gasification reactor (see Eq. 17). Eq. 18 presents the CO2 to carbon ratio φCO2C, which is defined as the introduced CO2 as gasification agent to C in the dry and ash-free fuel. Eq. 19 shows the C to CO conversion XC → CO, which describes the amount of produced CO in the product gas to the amount of C in the fuel and C in CO2 as gasification agent.

Factor kCO2 depending on temperature based on Neves et al. [42]

3 Results and discussion

Table 3 presents the main operational parameters for the steady state operation of the presented test campaigns 1 to 5. SW was gasified with pure olivine as well as a mixture of olivine and limestone to have a reference case for the gasification of the biogenic fuels and to be able to compare the results to pure steam gasification tests. Olivine forms Ca-rich layers, which improve the catalytic activity, via the interaction of the bed material particles with the woody biomass ash on the surface of the particles after days of operation [43, 44]. Additionally, Wagner et al. [45] and Kuba et al. [16] found out that also the fuel ash has an impact on the product gas composition due to an increased catalytic activity caused by layer formation. However, for the presented test campaigns, it was not possible to run the pilot plant continuously for a few days to simulate the operation of an industrial-sized gasification plant. Therefore, limestone was added to olivine as bed material to simulate the bed material after days of operation for the biogenic fuels SLI and BA with low ash contents. For RSC, which showed a higher ash content, only olivine was used as bed material.

The fuel power introduced into the GR (PGR) for all test campaigns was in a relatively similar range of 81 to 93 kW. The amount of additional fuel, which was introduced into the CR (PCR) to control the gasification temperature and to compensate the relatively high heat losses of the pilot plant was about 55 kW with a maximum for test campaign 3 of 71 kW. To enable a comparison of these test campaigns with test campaigns, where pure steam was used as gasification agent, a ratio between PCR and PGR was calculated. For pure steam gasification test campaigns, a PCR/PGR ratio of around 0.5 is a typical value, but it depends on the type of fuel introduced into the GR as well as the operating parameters [8, 28]. For the presented test campaigns, where a mixture of CO2 and steam was used as gasification agent, increased PCR/PGR ratios were calculated. This implies that the CO2 gasification requires more heat (see Eq. 14) than pure steam gasification (see, Eq. 15). The CO2/H2O ratios of the gasification agent introduced into the GR were kept quite similar for all test campaigns. The temperatures in the lower GR, “T GRlowera”, the temperatures in the upper GR, “T GRupper”, and the temperatures at the outlet of the CR, “T CRoutlet”, are displayed in Table 3 for all test campaigns. The measurement positions of the temperatures are shown in Fig. 2. The CO2 to fuel ratios φCO2F as well as the CO2 to carbon ratios φCO2C were in a range of 1.1 to 1.3 kgCO2/kgfuel and 1.8 – 2.1 kgCO2/kgC. The steam to fuel ratios φSF were between 0.3 and 0.5 kgH2O/kgfuel and the steam to carbon ratios φSC ranged between 0.6 and 0.9 kgH2O/kgC. These values account for the fluidization of the loop seals with steam. The H/C ratios were 0.09 and 0.10 for the fuels BA and SLI due to their high amount of C. For SW and RSC, a similar H/C ratio of 0.12 was calculated. The O/C ratios were in the same range for SLI, BA and RSC, but higher for SW, because SW exhibited the highest share of O.

3.1 Change of product gas composition

Figure 8 displays the product gas composition at the upper sample point (see Fig. 2) of the CO2/steam gasification test campaigns 1 to 5. The lowest contents of CO and CO2 were reached for test campaign 1. Due to the low amounts of O and C in the fuel RSC, a limited production of CO and CO2 was possible. The highest value of CO was generated in test campaign 5. SLI had a quite high amount of C and a low amount of O in the fuel, which resulted in the lowest O/C ratio (see Table 3). This as well as the higher temperatures could have affected the ongoing chemical reactions in a positive way. Additionally, the quite high amount of Na in the biomass ash of SLI could have also been a promoting factor to enhance CO formation. The promoting effect of alkali metals like Na on CO2 gasification was also found out by Huang et al. [18] and Mitsuoka et al. [7, 19]. The relatively high amounts of CO2 for test campaigns 2 and 3, where SW was used as fuel can be justified by the quite high O/C ratios in the fuel. Additionally, the increased values of CH4 for test campaigns 2 and 3 originate from a high H/C ratio in the fuel SW. The same phenomenon was described by Benedikt et al. [8] for steam gasification of different fuels. In contrast to that, test campaign 4 showed a low CH4 content due to a low H/C ratio. The addition of the catalytically active bed material limestone enhanced the formation of CO and H2 for test campaigns 3, 4 and 5. Low C2H4 values were reached for test campaigns 4 and 5, which could be due to the high temperatures as well as the addition of limestone to the bed material mixture. The lower heating values (LHV) were in the same range for all test campaigns between 9.2 and 9.9 MJ/m3stp,db (see Table 4). In Figs. 9 and 10, the correlation between the CH4 content and the H/C ratio and the correlation between the CO2 content and the O/C ratio is displayed. A higher H/C ratio in the fuel enhanced the production of CH4. The same trend was seen for the O/C ratio and the CO2 content in the product gas.

Figure 11 shows the product gas compositions at the lower sample point (see Fig. 2) for test campaigns 1 to 4. The product gas composition at the lower sample point was not measured for test campaign 5 due to blockage problems of the measurement point, which were most probably caused by the increased ash content of the fuel SLI. For test campaigns 2, 3 and 4, the H2 and CO2 contents were lower at the lower sample point and increased along the counter-current column to the upper sample point. Test campaign 3 showed the highest content of CO and the lowest content of CO2 at the lower sample point, which could be traced back to the quite low temperature in the lower GR compared to the other test campaigns (see Table 3). However, at the upper sample point, test campaign 3 showed a CO/CO2 ratio of almost 1/1. This could indicate that the WGS reaction was the dominant reaction in the upper GR, because according to Eq. 1 CO is converted to CO2 with a stoichiometric ratio of 1. Test campaign 1 showed lower H2, CO2 and CO contents at the lower sample point compared to the upper sample point. The CH4 contents were higher for all test campaigns 1 to 4 at the lower sample point. The C2H4 contents of all test campaigns were quite similar at the lower sample point but higher compared to the upper sample point. The higher CH4 and C2H4 contents at the lower sample point compared to the upper one for all test campaigns could be explained by steam and dry reforming reactions along the upper GR (see Eqs. 3 and 4).

3.2 Tar evolution of different biogenic fuels

In Fig. 12, the tar concentrations and calculated tar dew points (TDP) of test campaigns 1 to 5 are presented. The tar contents of test campaigns 1, 2, 3 and 5 were very similar. GC/MS tar concentrations of 8.5–9.0 g/m3stp,db and gravimetric tar concentrations between 4.1 and 5.8 g/m3stp,db were generated. For pure steam gasification of SW with olivine as bed material presented in [28], tar concentrations of 11.2 g/m3stp,db and 6.7 g/m3stp,db were generated. Hence, the tar contents of the presented test campaigns displayed in Fig. 12 were positively influenced by the use of CO2 and steam as gasification agent. This can be explained by dry reforming as well as steam reforming reactions (see Eqs. 3 and 4). As shown in Table 3, for test campaigns 3, 4 and 5, limestone was added to olivine as bed material. Typically, for pure steam gasification test campaigns, tar concentrations decreased when a catalytically active bed material like limestone was added [28, 30]. However, this effect was not observed for test campaigns 3 and 5. In these cases, the addition of catalytically active bed material limestone had no significant influence on tar concentrations. For test campaign 4, quite low tar concentrations could be achieved. This could have been caused through the CaO of the bed material limestone or the high amount of CaO in the biomass ash of bark, whereby the latter being the more likely one. Kuba et al. found out that Ca-containing feedstocks could lead to a substitution of the catalytic activity of the original particle, in our case, limestone as bed material, thanks to their ability to develop particle layers [46]. These layers could have been formed through the interaction of biomass ash with the bed material particles in fluidized beds. This layer formation through the interaction of the bed material particles with inorganic compounds of the biomass ash could explain the reduced tar concentrations of test campaign 4. Kirnbauer et al. found out that Ca-rich layers lead to an increased catalytic activity regarding tar decomposition [44, 47]. The tar dew points were similar for all test campaigns and ranged between 180 and 210 °C.

3.3 Hydrogen balance around the GR

For the gasification test campaigns, where a mixture of steam and CO2 is used as gasification agent, the question arises, if the WGS reaction plays an as important role as during pure steam gasification. Researches from Poland, France and Czech Republic are of the opinion that the WGS reaction is a central part during CO2 gasification [48,49,50]. To examine this topic, H balances were set up around the GR for a pure steam gasification test campaign (Fig. 13) as reference case and for the presented test campaigns 1 to 5 (see Fig. 14) based on validated data with IPSEpro. H in the fuel (H in fuel), H in H2O in the fuel (HH2O in fuel) as well as H in steam as gasification agent (H in steam) are regarded as input streams. H in H2O in the PG (H in H2O), H in H2 in the PG (H in H2), H in higher hydrocarbons in the PG (H in CxHy), H in tar and char in the PG (H in tar&char) as well as H transported to the CR via char together with the bed material (H to CR) are considered as output streams. For the interpretation of the H balances, only the WGS reaction was taken into account. It was assumed that when H in H2O was lower than the sum of HH2O in fuel and HH2O in steam, the introduced water into the GR was consumed to produce H2. For the reference case displayed in Fig. 13, the sum of H in steam and HH2O in fuel is higher than the amount of H in H2O in the PG. This could be explained by the WGS reaction (Eq. 1) because steam is consumed to produce H2.

However, when H in H2O was higher than the sum of HH2O in fuel and HH2O in steam, more water was produced then supplied to the GR. This would indicate that the WGS reaction took place in the opposite direction. For test campaigns 1, 3, 4 and 5, H in H2O was lower than the sum of HH2O in fuel and HH2O in steam. So, in these test campaigns, the WGS reaction took place. However, for test campaign 2, H in H2O was higher than the sum of HH2O in fuel and HH2O in steam, which indicates that the reverse WGS reaction took place. This finding can be linked to the negative water conversions for test campaign 2 displayed in Table 4. Negative water conversions are an indicator that H2O was produced during the test campaign. It is apparent that the content of H in CxHy was lower for CO2/steam gasification test campaigns (see Fig. 14) compared to that of the pure steam gasification test campaign (see Fig. 13). This could have been an effect of the dry reforming reaction (Eq. 4) and the resulting production of CO and H2. To sum up, these hydrogen balances present a first attempt to investigate the behaviour of the WGS reaction for CO2/steam gasification test campaigns. However, further investigations are recommended to prove these approaches.

To investigate the behaviour of the WGS reaction during CO2/steam gasification in more detail, the deviation from the WGS equilibrium was calculated (see Eq. 2 and Fig. 15) based on the product gas composition at the upper sample point depending on the gasification temperature “T GRlowera”. For test campaigns 3, 4 and 5, where catalytically active limestone/CaO was added to the bed material mixture, the deviation from the WGS reaction was lower compared to test campaigns 1 and 2, where pure olivine was used as bed material. This means that the catalytically active CaO had a positive effect on the WGS reaction. Additionally, increasing ash contents as well as increasing temperatures were beneficial to reach the WGS equilibrium state for all test campaigns. For test campaign 2, the highest deviation from the WGS equilibrium was calculated. This high negative value of pδeq, WGS indicates that the equilibrium was located on the side of the reactants, which fits to the finding of the H balance that the reverse water gas shift reaction took place for this test campaign (see Fig. 14). Additionally, the deviation from the BOU equilibrium pδeq, BOU (see Eq. 8 and Fig. 15) was calculated for all test campaigns as well. It is obvious that the deviations from BOU equilibrium were much higher than the deviations from the WGS equilibrium for all test campaigns. This points out that the WGS reaction could be the predominant gasification reaction for the presented test campaigns.

3.4 Performance indicating key figures

In Table 4, the performance indicating key figures are presented for test campaigns 1 to 5. The steam-related as well as the fuel-related water conversions were higher, when limestone was added to olivine as bed material. This can be explained by the presence of the catalytically active CaO, which enhanced the WGS and steam reforming reactions (Eqs. 1 and 3). The negative water conversion of test campaign 2 can be declared by the reverse water gas shift reaction, where H2O was formed. This result can be compared to the finding of the H balance as well as the high negative deviation from the WGS equilibrium (see Fig. 15). The CO2 and fuel-related CO2 conversion rates were in a range of 0.06 – 0 23 kgCO2/kgCO2 and 0.08 – 0.31 kgCO2/kgfuel,daf respectively. The lowest values for the CO2 and the fuel-related CO2 conversion rates were generated for test campaign 3, which could have been affected by the low gasification temperature. The highest value was reached for test campaign 5, which means that the highest amount of CO2 was converted. The product gas yields ranged between 1.5 and 1.9 m3stp,db/kgfuel,daf. The lowest value for the H2/CO ratio was generated for test campaign 2 of 0.63 and the highest value for test campaign 1 of 0.80. The highest LHV was reached for test campaign 3 due to the high amount of CO and CH4 in the product gas. Cold gas efficiencies between 75 and 94% could be reached.

4 Conclusions and outlook

The CO2/steam gasification of biogenic fuels was conducted successfully in the 100 kWth pilot plant at TU Wien. Five experimental campaigns were conducted using bark, lignin and rapeseed cake as fuel. Softwood was used as reference fuel. Pure olivine and mixtures (90/10 wt%) of olivine and limestone were used as bed material. The following results could be generated:

-

The composition of the product gas depended on the amount of C, H and O in the fuel. High amounts of C favoured the production of CO, high contents of O in the fuel enhanced CO2 formation and an increased share of H in the fuel promoted CH4 production. Additionally, the presence of alkali metals like K or Na in the biomass ash enhanced CO formation during CO2 gasification, which was also reported by Huang et al. [18] and Lahijani et al. [7].

-

The addition of the catalytically active bed material limestone to the bed material mixture as well as higher ash contents in the fuels favoured the ongoing chemical reactions, which resulted in higher CO and H2 contents.

-

Compared to tar concentrations of pure steam gasification test runs, the tar concentrations of CO2/steam gasification test campaigns were lower. The admixture of limestone to olivine showed no significant reduction of tar.

-

The hydrogen balances as well as the calculation of the deviations from the WGS and the BOU equilibrium of the presented test campaigns indicated that the water gas shift reaction could be the dominant reaction during CO2/steam gasification processes.

-

H2/CO ratios between 0.63 (test campaign 2) and 0.80 (test campaign 1) were generated.

-

The heating values ranged between 9.2 and 9.9 MJ/m3stp,db.

To sum up, for the formation of a high content of CO in the product gas, fuels with a high amount of C and increased contents of alkali metals in the biomass ash are recommended. Additionally, higher temperatures enhance the conversion efficiency. A possible application for a CO-enriched product gas could be the dimethyl ether (DME) synthesis to produce fuels and chemicals. Thereby, a H2/CO ratio of ~ 1 is necessary [51]. However, the synthesis gas can be used in other upgrading processes, where higher or lower H2/CO ratios are required, as well. The huge advantage of the DFB gasification reactor system is the possibility to adjust the H2/CO ratio in a broad range, which enables to use the synthesis gas in a lot different of applications. To investigate the CO2 gasification in the DFB reactor system in more detail, future research should focus on the gasification using pure CO2 as gasification agent and the influence of gasification temperature.

Abbreviations

- BA:

-

bark

- BOU:

-

Boudouard

- Ca:

-

calcium

- CR:

-

combustion reactor

- DFB:

-

dual fluidized bed

- DME:

-

dimethyl ether

- ECN:

-

Energy Research Centre of the Netherlands

- GC/MS:

-

gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry

- GR:

-

gasification reactor

- grav. tar:

-

gravimetric tar

- Gt:

-

gigatonne

- K:

-

potassium

- LHV:

-

lower heating value

- lime:

-

limestone

- Na:

-

sodium

- oliv:

-

olivine

- PAH:

-

polyaromatic hydrocarbons

- PGR :

-

fuel power introduced into GR

- PCR :

-

fuel power introduced into CR

- PGY:

-

product gas yield

- P:

-

phosphorus

- RSC:

-

rapeseed cake

- SLI:

-

straw-derived lignin

- SW:

-

softwood

- TDP:

-

tar dew point

- vol%:

-

volumetric percent

- WGS:

-

water gas shift

- wt%:

-

weight percent

- C:

-

carbon

- CR:

-

combustion reactor

- daf:

-

dry and ash-free

- db:

-

dry basis

- fuel:

-

fuel to gasification reactor

- GR:

-

gasification reactor

- H2O:

-

water

- PG:

-

product gas

- steam:

-

steam introduced into the gasification reactor

- stp:

-

standard temperature and pressure

- th:

-

thermal

- a,b:

-

stoichiometric factors (-)

- ṁ:

-

mass flow (kg/s)

- x:

-

mass fraction (-)

- kCO2 :

-

conversion factor of C to CO2 of fuel introduced into GR (-)

- V̇PG :

-

dry volumetric product gas flow (m3/s)

- XH2O :

-

steam-related water conversion (kgH2O/kgH2O)

- XH2O,fuel :

-

fuel-related water conversion (kgH2O/kgfuel,daf)

- XCO2 :

-

CO2 conversion (kgCO2/kgCO2)

- XCO2,fuel :

-

fuel-related CO2 conversion (kgCO2/kgfuel,daf)

- XC➔CO :

-

C to CO conversion (kgC,CO/kgC,fuel&fluid)

- φSC :

-

steam to carbon ratio (kgH2O/kgC)

- φSF :

-

steam to fuel ratio (kgH2O/kgfuel,daf)

- φCO2C :

-

CO2 to carbon ratio (kgCO2/kgC)

- φCO2F :

-

CO2 to fuel ratio (kgCO2/kgfuel,daf)

- ηCG :

-

cold gas efficiency (%)

- ηCG,o :

-

overall cold gas efficiency (%)

- Q̇loss :

-

heat loss (kW)

- LHV:

-

lower heating value (MJ/kg)

- PGY:

-

product gas yield (m3stp,db/kgfuel,daf)

- H2/CO ratio:

-

ratio of H2 to CO of product gas (-)

- PCR/PGR ratio:

-

ratio of power introduced into CR to power introduced into GR (-)

- H/C ratio:

-

ratio of H to C of the fuel (-)

- O/C ratio:

-

ratio of O to C of the fuel (-)

- pδeq,BOU :

-

deviation from Boudouard equilibrium (-)

- pδeq,WGS :

-

deviation from water gas shift equilibrium (-)

- Kp(T):

-

equilibrium constant of specific chemical reaction depending on temperature

- pi :

-

partial pressure of component i

- νi :

-

stoichiometric factor of component i

References

https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/jec/renewable-energy-recast-2030-red-ii. Accessed 1 Jan 2019

IEA. (2018) Global energy & CO2 status report 2017

Eurostat (2018) Frühzeitige Schätzungen der CO2-Emissionen aus energetischer Nutzung. Eurostat Pressemitteilung: 1–2

IPCC. (2014) Climate Change 2014: Synthesis report. doi:https://doi.org/10.1256/004316502320517344.

Steinberg M (1978) Synthetic carbonaceous fuels and feedstocks from oxides of carbon and nuclear power. Fuel 57:460–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-2361(78)90154-0

Butterman HC, Castaldi MJ (2009) CO2 as a carbon neutral fuel source via enhanced biomass gasification. Environ Sci Technol 43:9030–9037

Lahijani P, Alimuddin Z, Mohammadi M, Rahman A (2015) Conversion of the greenhouse gas CO2 to the fuel gas CO via the Boudouard reaction: A review. Renew Sust Energ Rev 41:615–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.08.034

Benedikt F, Schmid JC, Fuchs J, Mauerhofer AM, Müller S, Hofbauer H (2018) Fuel flexible gasification with an advanced 100 kW dual fluidized bed steam gasification pilot plant. Energy 164:329–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2018.08.146

Wilk V, Hofbauer H (2013) Conversion of mixed plastic wastes in a dual fluidized bed steam gasifier. Fuel 107:787–799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2013.01.068

Schmid JC, Wolfesberger U, Koppatz S, Pfeifer C, Hofbauer H (2012) Variation of feedstock in a dual fluidized bed steam gasifier - influence on product gas, tar content, and composition. Environ Prog Sustain Energy 31:205–215. https://doi.org/10.1002/ep.11607

Lunzer A. (2018) CPFD simulation in Barracuda VR of a novel dual fluidized bed cold flow model. TU Wien, master thesis.

Müller S, Groß P, Rauch R, Zweiler R, Aichernig C, Fuchs M (2017) Production of diesel from biomass and wind power – energy storage by the use of the Fischer-Tropsch process. Biomass Conv Biorefinery 8(2):275–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-017-0287-1

Gruber H, Groß P, Rauch R, Weber G, Loipersböck J, Niel J, et al. (2017) Fischer-tropsch synthesis – effects of feedstock load changes regarding product quality and catalyst attrition. Proc. 25th Eu Biomass Conf Exhib Stock. Sweden. doi:https://doi.org/10.5071/25thEUBCE2017-3AO.9.4.

Weber G, Rauch R, Hofbauer H (2015) Influence of ethylene on the formation of mixed alcohols over a MoS2 catalyst using biomass-derived synthesis gas. Biomass Conv Biorefinery 5:85–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-014-0140-8

Outokumpu HSC (2018) Chemistry Thermochemical Database, ver 6.1 A Roine - Finland: Outokumpu Research Oy.

Kuba M, Kirnbauer F, Hofbauer H (2017) Influence of coated olivine on the conversion of intermediate products from decomposition of biomass tars during gasification. Biomass Conv Biorefinery 7:11–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-016-0204-z

Franco C, Pinto F, Gulyurtlu I, Cabrita I (2003) The study of reactions influencing the biomass steam gasification process. Fuel 82:835–842. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-2361(02)00313-7

Huang Y, Yin X, Wu C, Wang C, Xie J, Zhou Z, Ma L, Li H (2009) Effects of metal catalysts on CO2 gasification reactivity of biomass char. Biotechnol Adv 27:568–572

Mitsuoka K, Hayashi S, Amano H, Kayahara K, Sasaoaka E, Uddin MA (2011) Gasification of woody biomass char with CO2: the catalytic effects of K and Ca on char gasification reactivity. Fuel Process Technol 92:26–31

Habibi R, Kopyscinski J, Masnadi MS, Lam J, Grace JR, Mims CA, Hill JM (2013) Co-gasification of biomass and non-biomass feedstocks: synergistic and inhibition effects of switchgrass mixed with sub-bituminous coal and fluid coke during CO2 gasification. Energy Fuel 27:494–500. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef301567h

Zhang R, Chen Y, Lei K, Liu D (2017) The effects of specific surface area and ash on char gasification mechanisms in the mixture of H2O, CO2, H2 and CO. Fuel 209:109–116

Cheng Y, Thow Z, Wang CH (2016) Biomass gasification with CO2 in a fluidized bed. Powder Technol 296:87–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2014.12.041

Ren L, Yang J, Gao F, Yan J (2013) Laboratory study on gasification reactivity of coals and petcokes in CO2/steam at high temperatures. Energy Fuel 27:5054–5068

Schmid JC. (2014) Development of a novel dual fluidized bed gasification system for increased fuel flexibility. TU Wien, doctoral thesis.

Pfeifer C, Schmid JC, Pröll T, Hofbauer H (2011) Next generation biomass gasifier. Proc 19th Eur Biomass Conf Exhib

Schmid JC, Pröll T, Pfeifer C, Rauch R, Hofbauer H. (2012) Cold flow model investigation on a modified riser with enhanced gas-solid contact – locating the regions of operation in a fluidization regime map. Proc 21st Int Conf Fluid Bed Combust, Naples, p. 88–87.

Pfeifer C (2005) Catalytic decomposition of tar from product gas of a dual fluidised bed biomass steam gasification process. TU Wien, doctoral thesis

Mauerhofer AM, Benedikt F, Schmid JC, Fuchs J, Müller S, Hofbauer H (2018) Influence of different bed material mixtures on dual fluidized bed steam gasification. Energy 157:957–968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2018.05.158

Fuchs J, Müller S, Hofbauer H (2017) Ash related limitations of dual fluidized bed steam gasification. 13 Minisymp für Verfahrenstechnik 2017

Benedikt F, Fuchs J, Schmid JC, Müller S, Hofbauer H (2017) Advanced dual fluidized bed steam gasification of wood and lignite with calcite as bed material. Korean J Chem Eng 34:2548–2558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11814-017-0141-y

Kolbitsch M, Schmid JC, Diem R, Müller S, Hofbauer H. (n.d.) Influence of fuel feeding position on sorption enhanced reforming in a dual fluid gasifier. Proc. 11th Int. Conf. Circ. Fluid. Bed Technol. (CFB11), Beijing, China, p. 1–6.

Tar Guideline, DIN CEN/TS 15439 2006.

Wolfesberger U, Aigner I, Hofbauer H (2009) Tar content and composition in producer gas of Fluidized bed gasification of wood — influence of temperature and pressure. Environ Prog Sustain Energy 28:372–379. https://doi.org/10.1002/ep.10387

Good J, Ventress L, Knoef H, Group BT, Zielke U, Hansen PL et al (2005) Sampling and analysis of tar and particles in biomass producer gases. Biomass Bioenergy 20002:1–44

Vassilev SV, Baxter D, Vassileva CG (2014) An overview of the behaviour of biomass during combustion : Part II. Ash fusion and ash formation mechanisms of biomass types. Fuel 117:152–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2013.09.024

Benedikt F, Kuba M, Christian J, Müller S, Hofbauer H (2020) Assessment of correlations between tar and product gas composition in dual fluidized bed steam gasification for online tar prediction. Appl Energy 238:1138–1149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.01.181

Kirnbauer F, Hofbauer H (2013) The mechanism of bed material coating in dual fluidized bed biomass steam gasification plants and its impact on plant optimization. Powder Technol 245:94–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2013.04.022

Pfeifer C, Koppatz S, Hofbauer H (2011) Steam gasification of various feedstocks at a dual fluidised bed gasifier: impacts of operation conditions and bed materials. Biomass Convers Biorefinery 1:39–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-011-0007-1

Fuchs J, Schmid JC, Benedikt F, Müller S, Hofbauer H, Stocker H, Kieberger N, Bürgler T (2018) The impact of bed material cycle rate on in-situ CO2 removal for sorption enhanced reforming of different fuel types. Energy 162:35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2018.07.199

Pröll T, Hofbauer H (2008) Development and application of a simulation tool for biomass gasification based processes. Int J Chem React Eng 6:Article A89. https://doi.org/10.2202/1542-6580.1769

Müller S, Fuchs J, Schmid JC, Benedikt F, Hofbauer H (2017) Experimental development of sorption enhanced reforming by the use of an advanced gasification test plant. Int J Hydrog Energy 42:29697–29707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.10.119

Neves D, Thunman H, Matos A, Tarelho L, Gómez-Barea A (2011) Characterization and prediction of biomass pyrolysis products. Prog Energy Combust Sci 37:611–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecs.2011.01.001

Kuba M, Havlik F, Kirnbauer F, Hofbauer H (2015) Influence of bed material coatings on the water-gas-shift reaction and steam reforming of toluene as tar model compound of biomass gasification. Biomass Bioenergy 89:40–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2015.11.029

Kirnbauer F, Wilk V, Kitzler H, Kern S, Hofbauer H (2012) The positive effects of bed material coating on tar reduction in a dual fluidized bed gasifier. Fuel 95:553–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2011.10.066

Wagner K, Fuchs J, Bartik A, Kuba M, Hofbauer H (2019) Influence of fuel ash and bed material on the water-gas-shift equilibrium in DFB steam gasification. Proc Int Conf Polygeneration Strateg

Kuba M, Havlik F, Kirnbauer F, Hofbauer H (2016) Influence of bed material coatings on the water-gas-shift reaction and steam reforming of toluene as tar model compound of biomass gasification. Biomass Bioenergy 2015:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2015.11.029

Kirnbauer F, Hofbauer H (2011) Investigations on bed material changes in a dual fluidized bed steam gasification plant in Güssing, Austria. Energy Fuel 25:3793–3798. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef200746c

Kamenikova P, Pohorely M, Skoblia S, Vosecky M, Puncochar M. (2008) Deliverable D 5.1 Report on results of fundamental studies on steam gasification.

Valin S, Bedel L, Guillaudeau J, Thiery S, Ravel S (2016) CO2 as a substitute of steam or inert transport gas in a fluidised bed for biomass gasification. Fuel 177:288–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2016.03.020

Jeremiáš M, Pohořelý M, Svoboda K, Skoblia S, Beňo Z, Šyc M (2018) CO2 gasification of biomass: the effect of lime concentration in a fluidised bed. Appl Energy 217:361–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.02.151

Ogawa T, Inoue N, Shikada T, Ohno Y (2003) Direct dimethyl ether synthesis. J Nat Gas Chem 12:219–227

Acknowledgements

This study has received funding from European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement number 764675 (Project Heat-to-Fuel).

Funding

Open access funding provided by TU Wien (TUW).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mauerhofer, A.M., Müller, S., Benedikt, F. et al. CO2 gasification of biogenic fuels in a dual fluidized bed reactor system. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 11, 1101–1116 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-019-00493-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-019-00493-3