Abstract

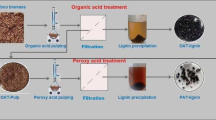

Olive pomace is a phytotoxic by-product in the olive oil production. Lignin is a biopolymer present in the olive pomace in remarkable percentages, which has a great variety of potential industrial uses. The extraction of lignin using the ionic liquid triethylammonium hydrogen sulfate resulted in recovery yields as high as 40% of the available lignin in the dry olive pomace. This percentage was obtained after optimizing conditions such as temperature, extraction time, and water content in the ionic liquid. This is the first time such a high percentage of extraction has been achieved when evaluating this type of feedstock. For comparison, two other extraction methods (sulfuric acid and alkaline treatments) were used to assess their extracting performances. Lignin was quantified after developing a rapid, robust, and reliable method by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (purity of 101 ± 16%) and characterized by proton nuclear magnetic resonance and gel permeation chromatography. The assay total phenolic content (TPC) revealed high content of phenolic groups (212 ± 26.9 mg of gallic acid equivalents per g of lignin). The high purity and TPC conferred on the extracted lignin a potentially high antioxidant activity. In addition, a 67-fold scale-up extraction of initial mass loading was performed obtaining same results as in the lower scale. Thus, the extraction of lignin using this methodology is expected to mitigate the disposal of the olive pomace and provide certain revenue to the oil mill.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

References

International Olive Council. World olive oil figures. http://www.internationaloliveoil.org/estaticos/view/131-world-olive-oil-figures. Accessed 18 Dec 2018

Molina-Alcaide E, Yáñez-Ruiz DR (2008) Potential use of olive by-products in ruminant feeding: a review. Anim Feed Sci Technol 147:247–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2007.09.021

Sierra J, Martí E, Garau MA, Cruañas R (2007) Effects of the agronomic use of olive oil mill wastewater: field experiment. Sci Total Environ 378:90–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.01.009

Cicerale S, Lucas L, Keast R (2010) Biological activities of phenolic compounds present in virgin olive oil. Int J Mol Sci 11:458–479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11020458

Cicerale S, Conlan X, Sinclair A, Keast R (2009) Chemistry and health of olive oil phenolics. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 49:218–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408390701856223

International Olive Council. Quality management guide for the olive-pomace oil extraction industry. http://www.internationaloliveoil.org/estaticos/view/222-standards. Accessed Feb 2019

Missaoui A, Bostyn S, Belandria V, Cagnon B, Sarh B, Gökalp I (2017) Hydrothermal carbonization of dried olive pomace: energy potential and process performances. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 128:281–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2017.09.022

Fernández-Hernández A, Roig A, Serramiá N, Civantos CGO, Sánchez-Monedero MA (2014) Application of compost of two-phase olive mill waste on olive grove: effects on soil, olive fruit and olive oil quality. Waste Manag 34:1139–1147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2014.03.027

Ma R, Xu Y, Zhang X (2015) Catalytic oxidation of biorefinery lignin to value-added chemicals to support sustainable biofuel production. ChemSusChem 8:24–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.201402503

Wang S, Shuai L, Saha B et al (2018) From tree to tape: direct synthesis of pressure sensitive adhesives from depolymerized raw lignocellulosic biomass. ACS Cent Sci 701–708. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscentsci.8b00140

Norgren M, Edlund H (2014) Lignin: recent advances and emerging applications. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci 19:409–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cocis.2014.08.004

Hart WES, Harper JB, Aldous L (2015) The effect of changing the components of an ionic liquid upon the solubility of lignin. Green Chem 17:214–218. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4GC01888E

Brandt-Talbot A, Gschwend FJV, Fennell PS, Lammens TM, Tan B, Weale J, Hallett JP (2017) An economically viable ionic liquid for the fractionation of lignocellulosic biomass. Green Chem 19:3078–3102. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7GC00705A

Weigand L, Mostame S, Brandt-Talbot A et al (2017) Effect of pretreatment severity on the cellulose and lignin isolated from Salix using ionoSolv pretreatment. Faraday Discuss 00:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7FD00059F

Prado R, Erdocia X, De Gregorio GF et al (2016) Willow lignin oxidation and depolymerization under low cost ionic liquid. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 4:5277–5288. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b00642

Sluiter A, Hames B, Ruiz R et al (2012) Determination of structural carbohydrates and lignin in biomass. In: Natl Renew Energy Lab. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/gen/fy13/42618.pdf. Accessed 26 Feb 2019

Le DM, Nielsen AD, Sørensen HR, Meyer AS (2017) Characterisation of authentic lignin biorefinery samples by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and determination of the chemical formula for lignin. Bioenergy Res 10:1025–1035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12155-017-9861-4

Zhou G, Taylor G, Polle A (2011) FTIR-ATR-based prediction and modelling of lignin and energy contents reveals independent intra-specific variation of these traits in bioenergy poplars. Plant Methods 7:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4811-7-9

Silva JC e, Nielsen BH, Rodrigues J et al (1999) Rapid determination of the lignin content in Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis (Bong.) Carr.) Wood by Fourier transform infrared spectrometry. Holzforschung 53:597–602. https://doi.org/10.1515/HF.1999.099

Bui NQ, Fongarland P, Rataboul F, Dartiguelongue C, Charon N, Vallée C, Essayem N (2015) FTIR as a simple tool to quantify unconverted lignin from chars in biomass liquefaction process: application to SC ethanol liquefaction of pine wood. Fuel Process Technol 134:378–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2015.02.020

Saad S, Issa R, Fahmy M (1980) Infrared spectroscopic study of bagasse and unbleached high-yield soda bagasse pulps. Holzforschung 34:218–222. https://doi.org/10.1515/hfsg.1980.34.6.218

Rodrigues J, Faix O, Pereira H (1998) Determination of lignin content of Eucalyptus globulus wood using FTIR spectroscopy. Holzforschung 52:46–50. https://doi.org/10.1515/hfsg.1998.52.1.46

Van Soest PJ, Robertson JB (1985) Analysis of Forages and Fibrous Foods, vol 613. Cornell University, Ithaca, pp 202

Van Soest P, Robertson J, Lewis B (1991) Methods for dietary fiber, detergent fiber, and non-starch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J Dairy Sci 74:3583–3597. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78551-2

Giavarina D (2015) Understanding Bland Altman analysis. Biochem Med 25:141–151. https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2015.015

Weerachanchai P, Lee JM (2017) Recovery of lignin and ionic liquid by using organic solvents. J Ind Eng Chem 49:122–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2017.01.018

Prado R, Brandt A, Erdocia X, Hallet J, Welton T, Labidi J (2016) Lignin oxidation and depolymerisation in ionic liquids. Green Chem 18:834–841. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5GC01950H

Sun R, Tomkinson J, Wang S, Zhu W (2000) Characterization of lignins from wheat straw by alkaline peroxide treatment. Polym Degrad Stab 67:101–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0141-3910(99)00099-3

Ainsworth E, Gillespie K (2007) Estimation of total phenolic content and otheroxidation substrates in plant tissues using Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. NatProtoc 2:875–877. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2007.102

Manzanares P, Ruiz E, Ballesteros M et al (2017) Residual biomass potential in olive tree cultivation and olive oil industry in Spain: valorization proposal in a biorefinery context. Span J Agric Res 15:1–12. https://doi.org/10.5424/sjar/2017153-10868

Brandt A, Gräsvik J, Halletta JP, Welton T (2013) Deconstruction of lignocellulosic biomass with ionic liquids. Green Chem 15:550–583. https://doi.org/10.1039/C2GC36364J

Kumar L, Arantes V, Chandra R, Saddler J (2012) The lignin present in steam pretreated softwood binds enzymes and limits cellulose accessibility. Bioresour Technol 103:201–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2011.09.091

Pinkert A, Goeke DF, Marsh KN, Pang S (2011) Extracting wood lignin without dissolving or degrading cellulose: investigations on the use of food additive-derived ionic liquids. Green Chem 13:3124. https://doi.org/10.1039/c1gc15671c

Sannigrahi P, Kim DH, Jung S, Ragauskas A (2011) Pseudo-lignin and pretreatment chemistry. Energy Environ Sci 4:1306–1310. https://doi.org/10.1039/C0EE00378F

Verdía P, Brandt A, Hallett JP, Ray MJ, Welton T (2014) Fractionation of lignocellulosic biomass with the ionic liquid 1-butylimidazolium hydrogen sulfate. Green Chem 16:1617. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3gc41742e

Abdelaziz OY, Hulteberg CP (2017) Physicochemical characterisation of technical lignins for their potential valorisation. Waste Biomass Valoriz 8:859–869. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-016-9643-9

Brandt A, Ray MJ, To TQ et al (2011) Ionic liquid pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass with ionic liquid–water mixtures. Green Chem 13:2489. https://doi.org/10.1039/c1gc15374a

Gschwend FJV, Brandt A, Chambon CL et al (2016) Pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass with low-cost ionic liquids. J Vis Exp 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3791/54246

Arni SA (2018) Extraction and isolation methods for lignin separation from sugarcane bagasse: a review. Ind Crop Prod 115:330–339

Poletto M, Ornaghi Júnior HL, Zattera AJ (2014) Native cellulose: structure, characterization and thermal properties. Materials (Basel) 7:6105–6119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma7096105

Chen S, Ling Z, Zhang X, Kim YS, Xu F (2018) Towards a multi-scale understanding of dilute hydrochloric acid and mild 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate pretreatment for improving enzymatic hydrolysis of poplar wood. Ind Crop Prod 114:123–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.02.007

Fan L, Gharpuray M, Lee Y (1987) Cellulose hydrolysis. Springer

Patil PT, Armbruster U, Richter M, Martin A (2011) Heterogeneously catalyzed hydroprocessing of organosolv lignin in sub- and supercritical solvents. Energy Fuel 25:4713–4722. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef2009875

Shimizu FL, Monteiro PQ, Ghiraldi PHC, Melati RB, Pagnocca FC, Souza W, Sant’Anna C, Brienzo M (2018) Acid, alkali and peroxide pretreatments increase the cellulose accessibility and glucose yield of banana pseudostem. Ind Crop Prod 115:62–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.02.024

Kia L, Jawaid M, Ariffin H, Alothman OY (2017) Isolation and characterization of microcrystalline cellulose from roselle fibers. Int J Biol Macromol 103:931–940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.05.135

García A, González Alriols M, Spigno G, Labidi J (2012) Lignin as natural radical scavenger. Effect of the obtaining and purification processes on the antioxidant behaviour of lignin. Biochem Eng J 67:173–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bej.2012.06.013

Ayoub A, Venditti RA, Pawlak JJ, Sadeghifar H, Salam A (2013) Development of an acetylation reaction of switchgrass hemicellulose in ionic liquid without catalyst. Ind Crop Prod 44:306–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.10.036

Faix O, Beinhoff O (1988) FTIR spectra of milled wood lignins and lignin polymer models (DHP’s) with enhanced resolution obtained by deconvolution. J Wood Chem Technol 8:502–522

Naumann A, Peddireddi S, Kües U, Polle A (2007) In: Kües U (ed) Wood production, wood technology, and biotechnological impacts. Universitätsveralg Göttingen, pp 179–196

Watkins D, Nuruddin M, Hosur M, Tcherbi-Narteh A, Jeelani S (2015) Extraction and characterization of lignin from different biomass resources. J Mater Res Technol 4:26–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2014.10.009

Casas A, Alonso MV, Oliet M, Rojo E, Rodríguez F (2012) FTIR analysis of lignin regenerated from Pinus radiata and Eucalyptus globulus woods dissolved in imidazolium-based ionic liquids. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 87:472–480. https://doi.org/10.1002/jctb.2724

Dutta T, Papa G, Wang E, Sun J, Isern NG, Cort JR, Simmons BA, Singh S (2018) Characterization of lignin streams during bionic liquid-based pretreatment from grass, hardwood, and softwood. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 6:3079–3090. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b02991

do Santos PSB, Erdocia X, Gatto DA, Labidi J (2014) Characterisation of Kraft lignin separated by gradient acid precipitation. Ind Crop Prod 55:149–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.01.023

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Catalan Government for the quality accreditation given to their research group 2017 SGR 828. This work has been partially funded by the Spanish government (CTQ2015-70982-C3-1-R, MINECO/FEDER). E.C. would like to thank “Banco Santander” for Grant X15016 in the framework of the “UdL Impuls” project. The “Cooperativa de l’Albi” is greatly acknowledged for fruitful discussions and kindly providing all olive pomaces.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

Enclosed in the supporting information there are complementary discussions, the FT-IR method validation, figures (Fig. S1–19) corresponding to ionic liquid, lignin and triglycerides spectra (FT-IR and NMR) and GPC determinations, and tables (Table S1–4) of the ratios flesh/stone, lignin content of the substrates determined by FT-IR and reference method, the T test: paired two samples for means, and the ionic liquid recovery and the effectiveness of the re-extractions. (DOCX 1730 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cequier, E., Aguilera, J., Balcells, M. et al. Extraction and characterization of lignin from olive pomace: a comparison study among ionic liquid, sulfuric acid, and alkaline treatments. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 9, 241–252 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-019-00400-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-019-00400-w