Abstract

Introduction

Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) is a crucial marker of glucose control that is widely utilized in the management of diabetes mellitus. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of a diabetes management program (DMP) offered by a health insurance company, together with the effects of other factors associated with patient and physician characteristics, on the frequency of HbA1c testing in outpatient diabetes clinics in Slovakia.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted to compare the frequency of HbA1c measurements in patients under the care of physicians participating in the DMP with those who did not, spanning the years 2015 to 2019. In 2019, a total of 74,384 patients with diabetes were included in the analysis, of which 52% were men and 48% were women, with an average age of 64.1 years.

Results

At the end of the study period, the average annual number of HbA1c measurements was significantly higher in patients treated by physicians participating in the DMP than in patients treated by physicians who were not (2.50 vs. 1.91 per year, respectively; P < 0.001). There was a substantial increase in HbA1c testing at least twice yearly in both groups, but the growth rate was greater in the group with DMP-engaged diabetologists (14.3%) compared to the diabetes specialists who were not involved in the DMP (5.1%). In the multivariate analysis, participation in the DMP was correlated with an increase in HbA1c tests per year by 0.7.

Conclusions

Physician participation in a DMP was found to significantly increase the number of HbA1c tests ordered by physicians, potentially leading to improved glycemic control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

The diabetes management program (DMP) offered to patients with diabetes by a health insurance company is designed to enhance the healthcare provided to Slovak patients living with diabetes. |

In the absence of clinical data, improved adherence to treatment guidelines serves as a solid indicator of enhanced healthcare delivery. |

What was learned from this study? |

While the frequency of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) measurements generally increased overall, the rate of increase was significantly higher among healthcare providers participating in the DMP compared to those who did not. |

Participation of healthcare providers in a DMP was found to significantly boost the number of HbA1c tests ordered these physicians, which could, in turn, lead to improved glycemic control. |

Introduction

Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) serves as a valuable marker of glucose control in that it reflects average glucose levels over the preceding 8 to 12 weeks [1]. However, when interpreting HbA1c levels, it is vital to recognize the influence of numerous clinical conditions and factors, such as erythrocyte lifespan, on HbA1c level [2].

Glycemic control plays a pivotal role in reducing the risk of microvascular complications in patients with both type 1 (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) [3, 4]. HbA1c concentrations also predict cardiovascular risk in patients with diabetes, thus helping the healthcare provider to identify individuals at a higher risk for cardiovascular disease who require specific interventions, such as those aimed at reducing blood pressure or cholesterol level [5].

The Slovakian Interdisciplinary Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus, its Complications, and Most Significant Comorbidities (2021) recommend standard HbA1c testing every 3 months, and once every 6 months in cases of sufficient and stable glycemic control in patients solely on lifestyle interventions. Pregnant women are the exception to these recommendations, with HbA1c testing recommended every 2 months [6].

According to the National Centre of Health Information (NCHI), 352,130 patients with diabetes (representing 6.45% of the population) were registered in Slovakia in 2020 as receiving systematic care from outpatient diabetes clinics. T2D was the most prevalent diabetes type (accounting for 91.1% of cases), while T1D was diagnosed in 7.4% of patients. Other types of diabetes mellitus were diagnosed in 0.9% of patients, and gestational diabetes mellitus in 0.6% of women [7]. For patients aged > 18 years, treatment falls under the competence of a physician specializing in diabetes, metabolic and nutritional disorders—commonly referred to as a "diabetologist." Patients younger than 18 years are treated by physicians specializing in pediatric endocrinology. Between diabetologist appointments, general practitioners monitor patient health and adherence to prescribed therapy, and prescribe the medications recommended by the diabetologist [8].

Several countries have implemented disease management programs (DMPs) focusing on changes in HbA1c levels or on the frequency of HbA1c testing [9,10,11]. A meta-analysis of 58 studies revealed that DMPs led to a significant reduction in HbA1c levels [12]. In that analysis, various factors were shown to reduce post-intervention levels of HbA1c. Of these, we incorporated the following interventions in our present study: patient education, clinician education (including the optimal number of HbA1c tests per year), electronic patient registry, and team changes. Due to privacy protection laws in Slovakia, we were unable to match the exact reimbursed HbA1c test with its result.

Therefore, the primary objective of this retrospective analysis was to assess the impact of a health insurance company's DMP on the differences in the frequency of HbA1c testing in Slovak outpatient diabetes clinics. Secondary objectives included identifying the factors contributing to these differences and relating these to the demographic characteristics of both patients and diabetologists.

Methods

Data Source

The healthcare system in Slovakia is based on universal coverage, compulsory health insurance (3 health insurance companies), a basic benefit package, and a competitive insurance model with selective contracting of healthcare providers. In 2015, Dôvera Health Insurance Company (DHIC) initiated a DMP for patients with diabetes that was called 'DôveraPomáha diabetikom' (Dôvera Helps Patients with Diabetes [DHPD]). This program was initially piloted in selected districts and during this first phase, 21 diabetologists, collectively treating > 11,000 DHIC policyholders with diabetes, were incorporated into the program [13]. Improvement in the quality of healthcare provided through the program was primarily ensured by implementing clinical protocols and quality healthcare indicators. Starting 1 July 2017, the number of HbA1c tests per year was introduced as a quality indicator. As a result, a diabetologist's remuneration within the program also depended on performing HbA1c testing at least once or twice a year for a selected group of patients with diabetes. On 1 September 2018, DHIC introduced a quality indicator that affected the remuneration of all contracted diabetologists (including those not participating in DHPD), dependent on the proportion of their patients with diabetes undergoing HbA1c testing at least once per year. Up to 2019, the total cost of DHDP program was 3.4 million euros.

The data used in this study were obtained from the DHIC database, which included healthcare benefits for the period 2014–2019. In 2019, 1,524,814 insured individuals were in the database. Unless specified otherwise, the analysis pertains to the situation as of 2019.

Roman Mužik in his official position as a manager responsible for the DHPD program has official permission to use the data from the DHIC database for publication purposes. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The data were obtained from the DHIC database, which reported healthcare benefits for the period 2014–2019 and included 1,524,814 insured individuals in 2019. This analysis was purely statistical as the health insurance company does not have access to clinical data, such as HbA1c levels, and therefore no ethical committee approval was required.

Patient Population

The patient sample consisted of patients aged > 18 years who had been diagnosed with T1D or T2D and were insured by DHIC throughout the study duration. Patients were classified as diabetic if they had received a diagnosis from a professional healthcare provider with International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) E10 or E11, excluding laboratory procedures. Newly diagnosed patients with diabetes were defined as those with no diagnosis of prediabetes or diabetes in the preceding 24 months. Treatment type was determined by examining the possible combinations of prescribed oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs), insulin or insulin pumps. The analysis included only patients with diabetes whose treatment could be associated to a specific diabetologist based on physical contact (i.e., laboratory examinations or procedures reported by a diabetologist outside teleconsultations). If a patient had contact with multiple diabetologists in a given year, they were assigned to the study on the basis of their last contact with their most recent diabetologist.

In 2019, the analysis enrolled 74,384 patients with diabetes (52% men, 48% women) with an average age of 64.1 years. The patient sample comprised 94% patients with T2D and 6% patients T1D. In terms of treatment type, the 2019 sample comprised 18% patients treated with lifestyle interventions only, 57% treated with OADs, 14% treated with OADs plus insulin, 10% treated with insulin only, and 1% treated with insulin pumps. The patient sample structure is detailed in Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) Table S1.

Characteristics of Participating Physicians

In 2019, 269 diabetologists working in 260 outpatient clinics had contracts with DHIC. This study included only outpatient clinics where the physician had at least ten patients insured by DHIC. In 2015, data from 229 diabetologists (177 women, 52 men; average age 52.1 years) were evaluated, of whom 21 physicians (17 women, 4 men) across 26 outpatient clinics were participating in the DHPD program. In 2019, data from 244 diabetologists (192 women, 52 men) were evaluated, of whom 34 physicians across 37 outpatient clinics were participating in the DHPD program. Characteristics of the participating physicians are given in detail in ESM TS1.

The reference period generally had a duration of 2 years. For 2019, the entire year was tracked for the purpose of identifying patients with diabetes and assigning them to a diabetologist. We retrospectively tracked whether HbA1c was measured over a current year from the last contact with a diabetologist in 2019. Based on this methodology, we only tracked HbA1c testing for patients who visited their diabetes specialist. Patients who did not attend diabetes clinics were excluded from this analysis.

Statistical Analyses

The primary outcome measured was the annual number of HbA1c tests per patient. The independent variables tested in the models included patient age, sex, number of diabetes clinic visits per year, type of diabetes treatment, patient's municipality/city, economic activity, and participation in the DHPD program. The physician's age, sex, and DMP identifier were also included in the models for comparison. The arithmetic mean and standard error of mean (SEM) were calculated for continuous variables. One-way and two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare arithmetic means, and the Chi-square test was used to compare frequencies. For multivariate analysis, we used the multiple linear regression model in R software ® Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Effect of the Disease Management Program

In 2015, at the study's inception, physicians participating in the DMP Dôvera Helps Patients with Diabetes (DHPD) program implemented HbA1c testing more frequently than those who were not participating in the DMP. Before the program's initiation, participating diabetologists tested a significantly larger proportion of their patients than did non-participating diabetologists in the specific regions where the program was initiated and who were not involved in the program throughout the follow-up period.

There was a significant increase in the average number of annual HbA1c measurements for both groups over the study period. However, by the end of the follow-up period, the difference in the mean annual HbA1c measurements between the two groups had grown (participating vs. non-participating physicians: 2.50 vs. 1.91 HbA1c measurements) compared to at the study's beginning (2.12 vs. 1.81 HbA1c measurements) (Table 1).

The percentage of patients tested for HbA1c at least once annually significantly rose in both groups over the duration of the study. By the end of the follow-up, 95.6% of the patients in the DMP participant group had been tested for HbA1c at least once a year, compared to 84.9% in the non-participant group. Both groups also showed a statistically significant increase in the proportion of patients tested at least biannually. However, the growth rate was greater in the group of participating diabetologists (an increase of 14.3%) than in the group of non-participating diabetes specialists (an increase of 5.1%) over the entire study period (Table 1).

Other Related Factors

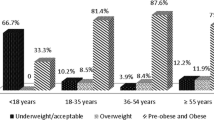

In 2019, the average frequency of HbA1c testing in patients with diabetes was 2.09 measurements per year. Statistically significant variations in the frequency of HbA1c measurements were observed among different groups of patients with diabetes, distinguished by factors such as age, treatment type, time, and economic activity (Table 2).

That same year, 89.0% of all patients in the study with diabetes underwent HbA1c testing at least once, and 68.3% were tested at least twice. Disparities in testing frequency were identified across various factors, predominantly with respect to treatment type, patient age, place of residence and socioeconomic status. The highest rate of annual HbA1c testing as well as HbA1c testing ≥ 2 times a year was generally found among patients using an insulin pump, patients in the age group 18–29 years, dependent children, and those living in western Slovakia's counties.

Significant disparities were also seen among diabetologists. In 2019, 64% of physicians performed HbA1c testing on > 95% of their patients at least once a year. Another 26% of physicians conducted HbA1c testing on 75–95% of their patients at least once a year, while 10% of physicians tested < 75% of their patients at least once a year (Fig. 1).

Multivariate Analysis of Factors Influencing the Frequency of HbA1c Measurements

We utilized multiple linear regression analysis to assess the factors influencing the number of HbA1c measurements in patients during 2019. The model incorporated factors related to both the patients and the physicians. Following backward elimination, the patient's sex was excluded from the model. This adjusted model accounted for 13% of the variance in the number of HbA1c measurements (Table 3).

The most substantial impact on the number of HbA1c measurements was attributed to participation in the DHPD program. The annual count of HbA1c tests was 0.69 higher in patients whose diabetologists participated in the DHPD. The treatment type also significantly influenced the number of measurements. Other notable predictors of the annual number of HbA1c measurements per patient are shown in Table 3.

When the variables representing the physician's sex and age were replaced with a variable identifying a specific physician, the model explained 59% of the variance in the number of HbA1c measurements. The "individual physician difference" variable alone accounted for 47% of the variance in this revised model. Hence, the interpersonal differences among physicians emerged as the principal factor influencing the number of HbA1c measurements, independent of the other factors examined.

Discussion

The findings from our study demonstrate that the DMP sponsored by an insurance company has significantly influenced the frequency of HbA1c measurements in diabetes patients. Compared with physicians not participating in the DMP, we found that physicians who were participating in the DMP were associated with a relatively higher frequency of HbA1c testing, performed on a relatively larger proportion of patients. Furthermore, the monitored variables also showed greater improvement after these physicians joined the DMP compared to those not participating in the program.

On average, participation in the DMP resulted in an increase of 0.69 HbA1c screenings per year. Moreover, among physicians in the program, there was a 14.3% rise in the proportion of patients receiving at least two HbA1c measurements annually, compared to a 5.1% increase with physicians outside the program.

Our findings are in agreement with those from previous research which indicates that less frequent HbA1c testing is significantly associated with poorer glycemic control [14] and that the frequency of HbA1c measurements and self-monitoring of glycemia are predictors of metabolic control [15]. Consequently, we hypothesize that our patients likely experienced improved glycemic control, despite the insurance company not having access to these data due to relevant legislation on privacy; this lack of data is the major limitation of the present study related to it’s design.

In our study in Slovakia in 2019, HbA1c levels were tested an average of 2.1 times per year in patients with T1D or T2D, a frequency that is notably higher than that reported in a number of other developed countries. For example, in Spain, HbA1c testing occurred an average of 0.9 times per year [16]; in the Canadian province of Alberta, patients with diabetes had their HbA1c tested more frequently, averaging 1.5 times per year [17]; and in a German study in 2016, HbA1c levels in T2D patients were reported to be tested at the even higher frequency of 2.7 times on average [18]. In yet another study involving 15,199 patients with T1D from Germany and Austria, quarterly HbA1c testing was associated with the best metabolic control [15].

A decade-long retrospective study from Japan (data from 2005–2014) suggested that one HbA1c monitoring event per year was sufficient for patients with T2D who had stable glycemic control, specifically those who achieved an HbA1c level of < 7.0% [19]. In Slovakia in 2019, 89.0% of patients with diabetes had at least one annual HbA1c measurement, while 68.3% had at least two. These figures vary considerably when compared to those from a South Korean study, which reported that 67.3% of patients had at least one HbA1c test per year, and 37.8% had at least two [20]. Conversely, our numbers were slightly lower than those of a German study in which 74% of patients had their HbA1c tested at least twice a year [18].

Numerous studies and meta-analyses focusing on the impact of DMPs on HbA1c have indicated that DMPs significantly reduce HbA1c levels [9,10,11]. In an analysis of 58 studies examining patients with T2D, the most substantial reductions in HbA1c levels were associated with changes in the primary treatment team (such as adding ≥ 1) and the introduction of case management. These elements were part of programs that decreased HbA1c levels by 0.67% and 0.52%, respectively [12].

Other factors that have been reported to contribute to HbA1c reduction include patient education, patient reminders, electronic documentation, and physician education [9]. A recent Australian study showed that adherence to guideline-recommended HbA1c testing not only improved glycemic control but also reduced the risk of chronic kidney disease [21].

Conclusion

In conclusion, by the end of our 2019 follow-up of a population of diabetes patients, HbA1c levels were being tested an average of 2.09 times per year, with 89.0% of these patients having had at least one HbA1c test per year, and 68.3% having had at least two. Over time, we observed an increasing trend in the proportion of patients tested for HbA1c at least once or twice a year. This increase was significantly more pronounced among physicians participating in the DMP Dôvera Helps Patients with Diabetes.

Based on our multivariate analysis, physician involvement in the DMP had the most substantial quantitative impact on the number of HbA1c measurements. We also noted variability in the frequency of HbA1c testing across a range of variables, with significant differences observed in the type of treatment, patient age, place of residence, and socioeconomic status.

Based on previous knowledge from interventional studies [3, 4], we hypothesize that increased frequency of HbA1c testing may have led to improved glycemic control in patients with both T1D and T2D. Whether this will translate into a reduction in diabetes-related complications will be a subject of future studies on the effects of DMPs.

References

McCarter RJ, Hempe JM, Chalew SA. Mean blood glucose and biological variation have greater influence on HbA1c levels than glucose instability: an analysis of data from the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:352–5.

Cohen RM, Smith EP. Frequency of HbA1c discordance in estimating blood glucose control. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11:512–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0b013e32830467bd.

Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group, Nathan DM, Genuth S, et al. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–86. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199309303291401.

UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet. 1998;352:837–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07019-6.

Khaw KT, Wareham N. Glycated hemoglobin as a marker of cardiovascular risk. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2006;17:637–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOL.0b013e3280106b95.

Martinka E (ed). Interdisciplinary recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of diabetes mellitus, its complications and most significant comorbidities—2021. Forum Diab. 2021;10(Suppl 2):1-279. https://www.prolekare.cz/casopisy/forum-diabetologicum/2021-supplementum-2-2/download?hl=cs.

National Health Information Center (NHIC). Activity of diabetes clinics in the Slovak Republic 2020. Health statistics yearbook 2020. 2021. https://www.nczisk.sk/Documents/rocenky/2020/Zdravotnicka_rocenka_Slovenskej_republiky_2020.pdf. Accessed 22 Feb 2022.

Ministry of Health of the Slovak Republic. Bulletins of the Ministry of Health of the Slovak Republic 2011. Volume 59. https://www.health.gov.sk/?VestnikyMzSr2011. Accessed 22 Feb 2022.

Steuten LMG, Vrijhoef HJM, Landewé-Cleuren S, et al. A disease management programme for patients with diabetes mellitus is associated with improved quality of care within existing budgets. Diabet Med. 2007;24:1112–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02202.x.

Kostev K, Rockel T, Jacob L. Impact of disease management programs on HbA1c values in type 2 diabetes patients in Germany. J Diab Sci Technol. 2017;11:117–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932296816651633.

Sidorov J, Gabbay R, Harris R, et al. Disease management for diabetes mellitus: impact on hemoglobin A1c. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6:1217–26.

Shojania KG, Ranji SR, Mcdonald KM, et al. Effects of quality improvement strategies for type 2 diabetes on glycemic control: a meta-regression analysis. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;296:427–40. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.4.427.

Tulejová H, Mužik R, Martinka E, Uličiansky V. Disease management programmes An opportunity to improve diabetes care. Int Med. 2017;17:259–64.

Fu C, Ji L, Wang W. Frequency of glycated hemoglobin monitoring was inversely associated with glycemic control of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Endocrinol Invest. 2012;35:269–73. https://doi.org/10.3275/7743.

Schwandt A, Best F, Biester T, et al. Both the frequency of HbA1c testing and the frequency of self-monitoring of blood glucose predict metabolic control: a multicentre analysis of 15 199 adult type 1 diabetes patients from Germany and Austria. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2017;33:7. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.2908.

García AB, Vega JS, Vigara JCR, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and frequency of glycated haemoglobin monitoring in Extremadura (Spain) during 2012, 2013 and 2014: an observational study. Prim Care Diabetes. 2019;13:324–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcd.2018.12.006.

Lyon AW, Higgins T, Wesenberg JC, et al. Variation in the frequency of hemoglobina1c (HbA1c) testing: population studies used to assess compliance with clinical practice guidelines and use of hba1c to screen for diabetes. J Diab Sci Technol. 2009;3:411–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/193229680900300302.

Kostev K, Jacob L, Lucas A, Rathmann W. Low annual frequency of HbA1c testing in people with type 2 diabetes in primary care practices in Germany. Diabet Med. 2018;35:249–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.13556.

Ohde S, Deshpande GA, Yokomichi H, et al. HbA1c monitoring interval in patients on treatment for stable type 2 diabetes. A ten-year retrospective, open cohort study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;135:166–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2017.11.013.

Yoo KH, Shin DW, Cho MH, Kim SH, et al. Regional variations in frequency of glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) monitoring in Korea: a multilevel analysis of nationwide data. Diab Res Clin Pract. 2017;131:61–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2017.06.008.

Imai C, Li L, Hardie R-A, Georgiou A. Adherence to guideline-recommended HbA1c testingfrequency and better outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: a 5-year retrospective cohort study in Australian general practice. BMJ Qual Saf. 2021;30:706–14. https://doi.org/10.1036/bmjqs-2020-012026.

Acknowledgements

Funding

The study was fully funded by DHIC (Dovera Health Insurance Company). No sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

The authors used Chat-GPT 4 to assist with the English language revisions in the manuscript.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design, with Roman Mužik and Ivan Tkáč making the major contributions. Data preparation and analysis were performed by Veronika Knapčoková and Beáta Saal. The first draft of the manuscript was prepared by Veronika Knapčoková, and all authors commented on previous versions of manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

Roman Mužik, Beáta Saal, and Veronika Knapčoková are employees of DHIC. Ivan Tkáč received lecture fees from Novo Nordisk and Boehringer Ingelheim, and consultation fees from DHIC.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Roman Mužik in his official position as a manager responsible for the DHPD program has official permission to use the data from the DHIC database for publication purposes. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The data were obtained from the DHIC database, which reported healthcare benefits for the period 2014–2019 and included 1,524,814 insured individuals in 2019. This analysis was purely statistical as the health insurance company does not have access to clinical data, such as HbA1c levels, and therefore no ethical committee approval was required.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to §76 of Act no. 581/2004 Coll., on Health Insurance Companies and Health Care Surveillance, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mužik, R., Knapčoková, V., Saal, B. et al. Effect of a Disease Management Program on the Adherence to Guideline-Recommended HbA1c Monitoring in Patients with Diabetes in Slovakia. Diabetes Ther 14, 1685–1694 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-023-01447-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-023-01447-9