Abstract

The objective of this study was to determine the effect of application of pesticides on morphology, viability, and germination of pollen grains of Blackberry (Rubus glaucus Benth.) and Tree tomato (Solanum betaceum Cav.). The study was performed at Patate, Tungurahua province, Ecuador and was divided into two phases. Phase one dedicated to the study of morphology, viability, and identification of nutrient solution for better germination of pollen grains and phase two for the analysis of the effect of conventional, organic, and biological pesticides on pollen grain germination and pollen tube length. To study pollen morphology, pollens were extracted by hand pressure and was analyzed by optical and electron microscopy. The viable pollen grains were identified by staining with 1% acetocarmine. Even though Tree tomato and Blackberry pollen grains are morphologically similar, their exine shapes differ. We observed four times increase in pollen germination rate when suspended in nutrient solution (Sucrose with Boric acid) than control (water). Pollen grains under nutrient solution were subjected to different groups of pesticides for the period of 2, 4, and 6 h. With respect to pesticide affect, the Blackberry pollen grain germination followed the following order: Lecaniceb > Beauveb > Metazeb => Myceb > Control. However, the effect on Tree tomato pollen grains was as follows: Lecaniceb > Myceb > Cantus > Bacillus thuringiensis > Kripton > Control. As per as pollen grain germination is concerned, we observed that the chemical pesticides are more harmful than other pesticides. So, it is necessary to perform screening test for different pesticides and their effect on pollen grain germination before applying to the fields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fruit species Rubus glaucus and Cyphomandra betaceae have an important nutritional and export potential in the Andean region of Ecuador. The cultures of these plants are held in very rustic conditions, without technical conditions in which they could improve their quality and performance. Today several institutions, especially the universities, are making efforts to develop technology and ecological approach to potentiate the possibility of export of Andean fruits without the use of chemicals that affect the germination of pollen grains. To achieve the above, the University is looking for resistant and highly productive vegetable materials by means of selective selection and multiplication of plants under controlled conditions (Soria 1996).

Blackberry (R. glaucus) was discovered and described by Hartw Benth, and it is native to tropical America, mainly in Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and Salvador (INCAP and FAO 1992). Genus Rubus is one of the largest numbers of species in the plant kingdom. They are scattered almost everywhere in the world except in desert areas (Angelfire 2001). In Ecuador, the Blackberry represents 95%. Other cultivars are Creole Blackberry (Rubus floribundus) “wild blackberries” (Rubus adenotrichus), “Olallieberry” (Rubus occidentalis), and “Brazos” (Rubus Olallieberry). The main producing areas in Ecuador are the provinces of Cotopaxi, Tungurahua, Chimborazo, Bolívar, Imbabura, and Pichincha (PAVUC 2008).

Tree tomato (Solanum betaceae) is a native species of Andes, whose domestication and cultivation predate the discovery of America. Of different denominations, the most used is tamarillo (Ecuador and Colombia); besides eggplant, “Sacha tomato,” “yunca tomato,” “tomatillo” (Peru); “Lime tomato,” “tomato mountain,” “tomato La Paz” (Bolivia, Argentina); and English: “tamarillo,” “tree tomato” (Debrot et al. 2005). Tomato tree (Cyphomandra betaceae Cav.) is native to South America: Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. In Colombia, tomatoes are recognized as red and common yellow, round yellow, parthenocarpic, and purple red. The molecular studies showed that Cyphomandra falls within the genus Solanum, because of this, their taxonomic classification was changed by transferring Cyphomandra and all its species to Solanum (Tobon and Vasquez 1998).

Blackberry and Tree tomato have a significant potential in Ecuador and demand worldwide. In 2012, INEC reported that Ecuador itself produced 5247 MT of Blackberry and 4280 MT of Tree tomato. These fruits are source of income for the producers in the province of Tungurahua, but pest infestation decreased the crop yield drastically and forced the excessive use of chemical, organic, and biological pesticides for control and at the same time it had a negative impact on environment. This has created a necessity to know the impact of these toxic pesticides on plant growth, the crop yield, and minimal quantity required for optimal effect. Even though pesticides are beneficial to control pests, how safe the crop is towards the pesticide application and the effects that these chemicals exert on fertilization of the pollen grains and setting up of fruit are still obscured. In relation with this, a study performed by Ricaurte (1999) on Tree tomato discloses that chemical pesticides can damage and lower the percentage of pollination, fertilization, setting up of fruit, and plant growth. This is evident by the application of copper-containing pesticide which stays on flowers and affects pollen grain germination (Arredondo 2008).

Fertilization is a complex biological process related to external factors such as weather and insects, or internal conditions of the plant or the compatibility of pollen (Palazón et al. 1991). During the application of pesticides, plants are in different stages of bloom, and how this will influence the germination of pollen grains by chemical, organic, and biological insecticides or pesticides is unknown. Flowering and setting up of fruit is a delicate physiological process in which it is estimated that pesticides can affect the viability and germination of pollen grains. A study on mango fruit orchards variety “Ataulfo,” reported that after more than 40 years of cultivation their production decreased from 15 tons to less than 4 tons which is due to the problem related to reproductive biology such as not having a good engraftment of flowers and fruit mooring (Malc Gehrke Rodney 2008). Simultaneously, they have characterized the morphology of the pollen grains, analyzed their viability, and measured the rate of germination and pollen tube growth for detecting malfunctions in the pollination process that generates lack of mooring and production of mango fruit.

Considering the importance of R. glaucus and S. betaceae, cultivation in Andean region and administration of pesticides drastically reduced the crop production by affecting fruit formation which is why it is imperative to diagnose the effect of these pesticides on crop performance. So, we thought of using chemical, organic, and biological pesticides in order to evaluate their effect on the morphology, germination, and viability of pollen grains (PG) in R. glaucus and S. betaceae.

Materials and methods

The research was conducted at the University of the Armed Forces-ESPE in the department of Agricultural Engineering-IASA-I. The study of the effect of conventional, organic, and biological pesticides on germination of R. glaucus and S. betaceae (Figs. 1, 2) pollen was performed in two phases. In the first phase, morphological characteristics of pollen such as shape, polarity, structure, and size and other characteristics such as viability and germination were studied. In the second phase, the effect of application of conventional, organic, and biological insecticides and fungicides on pollen germination was investigated.

The flowers were collected in the morning especially in the early hours from the field of Patate Canton, parish El Triunfo. In each sampling site, R. glaucus and S. betaceum plants were randomly selected in which open flowers were collected in the stage of anthesis. Inflorescences collection was performed in the morning to take advantage of anthesis which normally takes place at night or at dawn. The pollen grains (PG) were collected under the laminar air flow by pressing anther (dehiscence stage) lightly. An approximately 0.1 g of PG was collected from each type of plant and further transferred to the test tubes and Petri dishes of 5 cm of diameter containing different culture media. The nutrient media was made up of sucrose (10%) and H3BO3 (100 mg) dissolved in 100 ml of distilled water. Thus, the collected PG were oven dried in an incubator at 28 °C and their germination was observed at an interval of 2, 4, and 6 h by optical microscope (Jumping Model camera). The PG viability was determined by staining with 1% solution of acetocarmine, and the viable pollen grains acquire a red color of acetocarmine, whereas the transparent ones are nonviable and oval in shape.

Study of morphology and viability of pollen grains of R. glaucus and S. betaceae

For the first phase, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) and orthogonal contrasts for comparison between treatments (such as distilled water, nutrient media [10% of sucrose, and 100 mg of H3BO3 in 100 ml of distilled water] and flower tea) for pollen germination were performed. Statistical significance for the F test was set at 5% for pollen viability, form, color, and pollen tube dimension. The pollen suspension (0.1 g/ml) was prepared in a test tube containing 5 ml double distilled water and further incubated at 28 °C for 1 h. The aliquots of the suspension were placed on the glass slides and subjected for microscopic observation. Using an ocular micrometer, the morphology data for every 100 un-germinated pollen grains were recorded, and the diameter, length, and width were determined in micrometer (µm) and PG viability through 1% solution of acetocarmine. A scanning electron microscopy was used to further ratify the PG morphology.

Study of effect of pesticides on morphology of pollen grains

The effect caused by pesticides (chemical fungicides, organic fungicides, and biological insecticides) in phytosanitary controls in R. glaucus and S. betaceae on the morphology of the pollen grains was determined using following treatment groups: P1—six chemical fungicides, P2—six organic fungicides, P3—six biological insecticides, and P0—Control. All the treatments were performed in Petri dishes containing nutrient media and the appropriate concentration of pesticides is indicated in Table 1. The experimental design was implemented using a completely randomized design (CRD) with 3 replications.

For phase 2, the testing of hypotheses performed using Bartlett’s test and for homogeneity of variance test 5% of statistical significance was considered. After checking the lack of homogeneity, nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test was performed with the same level of significance. Finally, for the paired contrasts Mann–Whitney U test was performed with adjustment of statistical significance because of the many contrasts. Statistical analysis was performed using the Agricolae packet under the R software version R.3.0.1.

Results and discussion

Determining the shape of the pollen grains of Blackberry and Tree tomato

Rubus glaucus pollen grains have tricolporate form with three pores and three visible colpi; they are isopolar with radial symmetry, ornamentation-ribbed, medium-sized; and their diameter was 27.51 μm, and the pollen tube was 55 μm long and 9.17 μm wide. This is similar to the findings of Gonzales and Candau (Gonzales and Candau 1989). Tomlik and Ham (2004) have studied nine European species of the genus Rubus under electron microscopy and confirmed that all grains are small in size, isopolar, and tricolporate in appearance (Fig. 3).

Tree tomato pollen grains was seen with a microscope lens by Yuenping mark 10× and 40× field a form subtriangular or subcircular with a polar diameter 27.51 μm, tricolporate, has a psilate exine ornamentation, which is in support of Del Hierro (2013) who measured through electron microscope and obtained a polar diameter of 27.91 μm and a psilate ornamentation, along with exine thickness of 1.48 µm (Fig. 4).

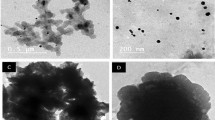

Electron microscopy

In order to ratify the pollen grains morphology, they were observed under scanning electron microscope and found both pollen grains are different in their exine architecture as seen in Fig. 5.

Untreated Blackberry and Tree tomato pollen grains under scanning electron microscope: a Tree tomato anther, b Tree tomato pollen, c Blackberry pollen grain, d single Tree tomato pollen grain, e Blackberry pollen grain with visible tricolporate, three colpi, and three pores indicated by an arrow, f Tree tomato pollen grain with elongated colpi

Effects of pesticides on pollen morphology of Blackberry

Prominent morphological defects were observed after 6 h of exposure, and at the concentration of 0.0125 g/mL of pesticides, a prominent decrease was witnessed in the elongation (55 microns average) and germination of pollen tube in the nutrient medium. Cantus, Beauveb, Metazeb, and Lecaniceb did not affect normal pollen tube elongation, whereas Myceb affected the normal shape of pollen tube and other morphological features. Myceb caused abnormal shape and multiple deformations of pollen tube. Benzimidazole and Fungbacter affected the pollen grains germination and did not affect elongation of pollen tubes. Chlorothalonil, Copper hydroxide, Pyraclostrobin, Epoxiconazole, Dimethomorph, Mancozeb, and Milagro inhibited pollen grain germination and significantly caused pollen tube deformation. Bitertanol, Kripton, Excellent, Milsana, Bacillus thuringiensis, and Neem extracts cause ruptured pollen grains, which are shown in Fig. 6.

Blackberry pollen grains under light microscope from both control and treated with different pesticide groups: a Control, a normal pollen grains and pollen tube after 6 h exposure in the nutrient medium, indicated by an arrow. b Cantus-, Metazeb-, Beauveb-, and Lecaniceb-treated groups do not show any effect on normal pollen tube elongation, indicated by an arrow. c Myceb caused abnormal pollen tube shape, indicated by an arrow. d Myceb caused multiple deformations of pollen tube, indicated by an arrow. e Benzimidazole and Fungbacter affected pollen grain germination and inhibited pollen tube elongation, as indicated by an arrow. f Chlorothalonil, Copper hydroxide, Pyraclostrobin, Epoxiconazole, Dimethomorph, Mancozeb, and Milagro inhibited pollen grain germination and caused pollen tube deformation, as indicated by an arrow. g Bitertanol, Kripton, Excellent, Milsana, B. thuringiensis, and Neem extracts cause ruptured pollen grains, as indicated by an arrow

Effects of pesticides on pollen morphology of Tree tomato

In a control treatment (10% sucrose plus 100 ppm of boric acid), 57.10% germination was observed and the pollen tube reached an average length of 81.99 µm. Prominent morphological defects were observed after 6 h exposure to 0.0125 g/mL of pesticides like Cantus, Lecaniceb, and Kripton allowed an excellent germination and growth of large pollen tubes. Myceb and B. thuringiensis allowed a normal initial pollen tube elongation, but subsequent destruction; Benzimidazole, Beauveb, and Metazeb caused low percentage of germination and blocked pollen tube elongation. Chlorothalonil, Copper hydroxide, Pyraclostrobin, Epoxiconazole, Dimetomorf, Mancozeb, Bitertanol, Milagro, and Fungbacter caused deformation of pollen grains and blocked the germination process. Similarly, Milsana, Neem extract, and Metazeb caused abnormal shape and disintegration of pollen grains (Fig. 7).

Tree tomato pollen grains under light microscope from both control and treated with different pesticide groups: a Control, b Cantus-, Lecaniceb-, and Kripton-treated groups showed excellent germination and growth of large pollen tubes, as indicated by an arrow. c Myceb and B. thuringiensis allowed a normal initial pollen tube elongation, but subsequent destruction, as indicated by an arrow. d Benzimidazole and Beauveb caused low percentage of germination and blocked pollen tube elongation, as indicated by an arrow. e Chlorothalonil, Copper hydroxide, Pyraclostrobin, Epoxiconazole, Dimethomorph, Mancozeb, Bitertanol, Milagro, and Fungbacter caused pollen grain deformation, and also blocked germination process as indicated by an arrow. f Excellent, Milsana, Neem extract, and Metazeb caused abnormal shape and disintegration of pollen grains as indicated by an arrow

Determination of the suitable nutrient solution for pollen germination

According to the test of significance of 5% Tukey, two ranges of statistical significance were observed (Fig. 8). The average pollen germination observed under flowers tea and distilled water was 5.76 and 6.84%, respectively, while in the nutrient media (10% sucrose and 100 mg of boric acid) it was 28.68%, which is in support of the findings of Soria (1996) and Ricaurte (1999). For germination of Blackberry and Tree tomato pollen grains, the nutrient media was used further as it gave very good results as compared to distilled water and flower tea.

Study of effect of pesticides on Blackberry pollen grains

Germination rate of pollen grains

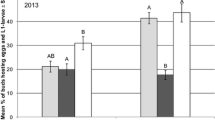

On comparison with P0 vs P1, P2 and P3 at 2 and 4 h incubation period did not present statistical differences, and on comparing P1 and P2 at 2 h incubation time differed only at 5% and at 6 h did not show any statistical significance (Table 2, Fig. 9).

The test of homogeneity of variance Bartlett (p value = 0.00) shows that there is no homogeneity of variances between groups. The test for nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis half (50.8, p value = 0.00) indicates that there are statistically significant differences between treatments. As depicted in Table 3 and Fig. 10, which shows 5 ranks of statistical significance for the individual treatments. Upon treatment with Metazeb and Lecaniceb, average germination was between 50 and 56%. For Beauveb and Myceb, it was between 43 and 46%. Similarly, an average germination between 35 and 43% was observed in the case of pyraclostrobin, dimethomorph, and cantus treatments. The remaining treatment groups showed lower germination of 23%.

Study of effect of pesticides on R. glaucus pollen tube length

The statistical analysis of data was performed using the Bartlett homogeneity of variance test and is presented in Table 4. Only Metazeb-, Cantus-, Bacillus-, and Carbendazim-treated pollen grains showed pollen tubes with less than 8 µm in length and did not affect its germination. However, other treatments showed greater pollen tube length. The maximum pollen tube length of 22.17 µm was observed in case of TES treatment.

Study of effect of pesticides on S. betaceum pollen grains

Germination rate of pollen grain

Germination rate of Tree tomato pollen grains was assessed at 2, 4, and 6 h with different groups of pesticides. The Conventional pesticides did not show any statistical significance in each of the assessments, while there is 1% difference between ecological and biological pesticide-treated groups (Table 5).

Chemical pesticides did not allow proper germination of Tree tomato pollen grains, while biological pesticides had similar values compared to control, which indicates that the biological pesticides did not affect the percentage of germination of pollen grains and on the contrary organic pesticides showed intermediate results (Table 6; Fig. 11).

The Bartlett variance test showed no similarity between groups. The nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test indicates statistically significant differences between means of different treatments. As showed in Table 7, the pesticides that showed significant differences for treatments at 6 h are Lecaniceb Cantus, Myceb, B. thuringiensis, Kripton, and control. The pesticides whose treatment showed the lowest levels of Tree tomato pollen grains germination are Bitertanol, Dimethomorph, Mancozeb, Hidroximetal Alkyl Dimethyl N, Azadirachtin, Metalsulfoxilate, Boscalid, Hydroxide copper sulfate-N Metal uncle, acid-sulfinic-hydroxymethane-ammonium-alkyl dimethyl benzyl Extract Reysa, and Pyraclostrobin Epoxiconazole.

Figure 12 shows that Lecaniceb, Myceb, Cantus, Bacillus, and control showed a very good germination of pollen grains.

Study of effect of pesticides on S. betaceum pollen tube length

In Fig. 13, it shows that the pollen tube length of control group showed an average of 27.83 µm, and similar pollen tube length was also observed in the treatment groups containing pesticides such as Lecaniceb, Myceb, Bacillus, Kripton. A relatively lesser that is 8.25- to 5.5-µm-long pollen tube length was due to the result of treating pollen grains with Cantus, Carbendazim, Beauveb, Chlorothalonil, and Metazeb. The remaining pesticides did not allow the germination of pollen grains.

Conclusions

The best nutrient solution for R. glaucus Benth. and S. betaceum Cav. pollen grains germination was sucrose and boric acid solution. The Rubus glaucus pollen grains are tricolporate, isopolar, exhibit radial symmetry, exine-ribbed, medium-sized, and 27.51 μm diameter in size, with the pollen tube of 55 μm in length and 9.17 μm in width. The Tree tomato pollen grains were tricolporate, subcircular, or subtriangular in shape, of 27.51 μm in diameter, exhibit psilate exine ornamentation, are small-to-medium sized, with pollen tube of 27.83 μm in length and 9.77 μm in width. The highest percentage of pollen germination in R. glaucus Benth. was observed against the treatment of biological pesticides and control groups, whereas the lowest percentages were obtained in groups treated with organic pesticides. With respect to pollen tube length in R. glaucus, the highest tube length was observed in control as well as in Myceb-treated group. The second highest was observed in Lecaniceb-treated group and the third highest in Beauveb- and Pyraclostrobin-treated groups. The Metazeb-, Cantus-, Bacillus-, and Carbendazim-treated groups showed relatively smaller pollen tube length which indicates the adverse effect of these pesticides on pollen germination. We observed that chemical pesticides inhibit Tree tomato pollen grain germination, while biological pesticides do not affect. Similarly, organic pesticides also affect the normal development of pollen grains. So, it is necessary to check how safe is the pesticide to pollen grains before applying to crop or different pesticides need to be screened for their effect on pollen grain germination.

References

Arredondo B (2008) Polinicide effect of copper salts in CV Hass avocado flowers. Thesis Retrieved November 2013 in Quillota–Chile. pp 11–12. http://ucv.altavoz.net/prontus_unidacad/site/artic/20080812/asocfile/20080812094258/sarredondo.pdf

Debrot A, Arnal E, Solorsano R, Ramoa F (2005) Diagnosis of diseases of Tree tomato in Venezuela Aragua and Miranda states. Retrieved May 2011, from INIA-CINIAP. Revista Digital del Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Agropecuarias de Venezuela. http://www.rlc.fao.org/ is/agriculture/produ/cdrom/content/Book 10/cap03_ 4.htm

Del Hierro CAG (2013). Morphological study of the impact of conventional, biological and ecological pesticides in pollen grain tomato tree. Thesis, Biotechnology Engineering, University of the Armed Forces-ESPE

Gonzales, Candau P (1989) Palynology contribution to the Rosaceae. Acta Botánica Malacitana, 14, pp 105–116. Malaga. Universidad de Sevilla, Publicada 11 de enero de 1989. http://www.biolveg.uma.es/abm/Volumenes/vol14/14_Gonzalez.pdf

INCAP and FAO (1992) Cultivation of Blackberry, Rubus glaucus. Retrieved June 2011 Table of food composition ICBF 6ta Ed.: http://www.angelfire.com/ia2/ingenieriaagricola/mora.htm

Malc Gehrke Rodney V (2008) Reproductive phenology of ataúfo handle associated with the incidence of child handle. Produce Chiapas http://www.fec-pag7-16chiapas.com.mx/sistema/biblioteca_digital/fenologia-reproductiva-del-mango-ataulfo.pdf

Palazón I, Palazón C, Balduque R (1991) Pesticides applied in bloom and pollination. In: Aragon SD (ed) Retrieved on February 25, 2012, 27 page. http://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/clc/566752

PAVUC (2008) With commercial fruit crops Underutilised potential Andean Blackberry (Rubus spp.). Retrieved January 2012 from pp 3–4 http://cordis.europa.eu/docs/publications/1206/120694401-6_en.pdf

Ricaurte C (1999) Study of the morphology of the pollen grain in Tree tomatoes (Cyphomandra betacea) and the effect of the application of fungicides on germination. Thesis. Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, pp 16 (22): 57–67. Sangolqui- Ecuador

Soria N (1996) Influence of pesticides on germination of pollen grains in the Tree tomato Cyphomandra betacea SENT. Benjamin Araujo Higher Agricultural Technical Institute, Patate

Tobon C, Vasquez G (1998) Factors associated with the generation and adoption of Technology in exotic fruit, Bibliotheca digital. Agronet. Antioquia: CORPOICA. pp 13–15

Tomlik W, Ham WV (2004) Pollen morphology of the genus Rubus L. In: Poloniae AS (ed) Obtained from studies Malesian kind of subgenres Chamaebatus L. and L. Idaeobatus 73 (3): 207–227. https://pbsocietyorg.pl/journals/index.php/ASBP/article/view/asbp.1995.027

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the Universidad de las Fuerzas Armadas-ESPE for providing all the necessary facilities throughout the research work. We are also grateful to Emilio Basantes, Sara Guerra, and Marco Taco for their valuable technical assistance. The co-author (Bangeppagari Manjunatha) greatly acknowledges the Korea Research Fellowship Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Padilla, F., Soria, N., Oleas, A. et al. The effects of pesticides on morphology, viability, and germination of Blackberry (Rubus glaucus Benth.) and Tree tomato (Solanum betaceum Cav.) pollen grains. 3 Biotech 7, 154 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-017-0781-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-017-0781-y