Abstract

Persistent human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is responsible for the majority of oropharyngeal and cervical cancers in the USA. Currently, HPV curricula within medical and dental schools are not standardized. As such, we implemented a brief online educational intervention to increase medical and dental trainees’ knowledge of the HPV vaccine and the association between HPV and cancer. The objectives of this study were to (1) assess medical and dental trainees’ baseline knowledge regarding HPV and HPV vaccine, (2) determine the willingness to recommend the HPV vaccine to patients, and (3) evaluate the impact of an online intervention on HPV-related knowledge. Medical and dental trainees from two large academic centers in the USA were asked to fill out an online pre-intervention questionnaire, followed by a 10-min HPV educational intervention based on the Center of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) resources, and then a post-intervention questionnaire. There were 75 participants (67.4% females; median age 18–30 years). When asked about HPV-related cancer types, the correct response increased from 28.4% (pre-intervention) to 51.9% (post-intervention; p < 0.01). When asked about the prevalence of HPV infections, the correct response improved from 36 to 72% (p < 0.01). There was also a 25.2% improvement in identifying the correct HPV vaccination dosing schedule (p < 0.01). Eighty-seven percent of the participants mentioned that the online education improved their HPV knowledge, and 68.5% reported that they were more likely to recommend HPV vaccine after the online intervention. The proposed online educational intervention was effective at improving HPV-related cancer and HPV vaccine knowledge as well as attitudes towards vaccine recommendation among dental and medical trainees and could be implemented in medical and dental school curricula in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the world [1]. Infection with high-risk HPV (HRHPV) subtypes is associated with cervical, vaginal, vulvar, penile, anal, and oropharyngeal cancers [2, 3]. In the USA, HPV associated oropharyngeal cancer rates have now surpassed the rates of cervical cancer, with an annual incidence of 14,400 cases for oropharyngeal cancer [4].

The 9-valent HPV vaccine (Gardasil 9, 9vHPV; Merck, VA) protects against 9 HPV subtypes and has been shown to prevent most HPV associated cancers [5]. Despite the recommendations endorsed by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), the HPV vaccine uptake in the USA remains lower than the Healthy People 2030 proposed goal of 80% [6]. Only 48% of adolescents aged 13 through 15 years in the USA received recommended doses of the HPV vaccine by 2018 [6].

Studies have shown that a healthcare provider’s recommendation is the number one factor influencing HPV vaccination uptake [7]. Healthcare providers with higher knowledge of HPV are more likely to recommend the vaccine [8]. However, both medical and dental providers have an overall poor baseline knowledge on HPV and the HPV vaccine [9, 10]. As such, we decided to investigate the overall knowledge on HPV of medical and dental trainees from two institutions in the USA. We hypothesized that a brief online education intervention would improve medical and dental trainees’ baseline HPV knowledge and, therefore, increase the likelihood of them recommending HPV vaccines to their patients in the future. In addition, given the age of trainees, they might also be more likely to undergo vaccination themselves, based on what they learned, and this might further increase the likelihood of recommending vaccination in the future. The aim of this pilot study was to (1) assess medical and dental trainees’ baseline knowledge regarding HPV and HPV vaccine, (2) determine the willingness to recommend the HPV vaccine to patients, and (3) evaluate the impact of an online intervention on HPV-related knowledge.

Methods

Questionnaires and Online Educational Intervention

We developed an online interactive educational module, using online flashcards based on the pre-existing CDC resources on the HPV and HPV vaccine. The topics on each flashcard ranged from HPV-related cancer knowledge to HPV vaccine recommendation and scheduling (see Appendix 1). The flashcards were designed to provide necessary information for medical and dental trainees to understand the prevalence and burden of HPV infection and also the safety and effectiveness of the HPV vaccine. The online education module also included a brief video from the CDC on how to recommend the HPV vaccine to patients.

Pre-intervention and post-intervention questionnaires were administered to each participant. The pre-test questions assessed participants’ baseline knowledge of HPV-related topics and assess participants’ willingness to recommend the HPV vaccine. Following the intervention, participants completed post-test questions. These questions again assessed the HPV-related knowledge as well as willingness to recommend the vaccine.

Subjects

Eligible medical and dental trainees from University of California, San Francisco, and Harvard School of Medicine and Dental Medicine were contacted via email. Actively enrolled medical and dental trainees from either institution who were 18 years of age or older and able to give informed consent were eligible for the study. The email invitations for the study were sent from the programs’ administrators to their respective cohorts of dental and medical trainees. The study was approved by the International Review Board at each participating institution.

Study Protocol

The email detailed the study’s protocols including objectives, goals, and consent. An attached link connected participants to a secure Qualtrics survey. An informed consent was included and signed electronically on the first page of Qualtrics and was obtained from all individual participants included in this study. Online instructions guided participants through initial demographics questions (e.g., age, preferred gender, department). All responses collected were anonymous. The survey included a pre-intervention questionnaire, followed by an educational intervention as described above, and a post-intervention questionnaire. The total time to complete the online intervention and questionnaires was approximately 10 min. The survey was collected from 19th June 2021 to 18th December 2021.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic data, pre-intervention, and post-intervention questionnaire responses. Difference in pre- and post-intervention questionnaire responses were assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient. P values were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Results

Demographics

Seventy-four trainees participated and completed pre-intervention questionnaire. Fifty-five (74.3%) were in the 18–30 years age range and 52 (70.3%) identified as female (Table 1). Out of 74 participants, 58 (78.4%) were dental trainees, and 10 (13.5%) were medical trainees. Half of the participants (32/74; 43.2%) had received more than 1 dose of HPV vaccine, while 9 (12.2%) had not received any HPV vaccines, and 9 (8.1%) did not know their HPV vaccination status. A total of 54 (73.0%) participants completed the pre-questionnaire, educational intervention, and post-questionnaire.

Questionnaire Results

When asked about HPV-related cancer types, 30.3% of participants answered correctly during the pre-intervention compared to 51.9% in the post-intervention survey (p < 0.01) (Table 2). When asked about the prevalence of HPV infections, there was a statistically significant increase in number of correct responses after the educational intervention (from 36 to 72%; p < 0.01). However, when asked about who should receive the HPV vaccine, the online intervention did not seem to improve the knowledge this specific topic. Eleven out of 74 respondents (14.8%) answered correctly in the pre-intervention questionnaire, while only 5 out of 54 (9.3%) answered correctly in the post intervention questionnaire (p < 0.01).

Forty-five of the 54 post-intervention responses (83.3%) correctly answered questions about the HPV vaccine schedule, compared to 43/74 (58.1%) pre-intervention responses (p < 0.01). More than 90% of all cervical cancers diagnoses in the USA are associated with HRHPV infection [11]; 15 of 74 (20.2%) answered this correctly in the pre-intervention questionnaire compared to 27/54 (50.0%) in the post-intervention questionnaire (p < 0.01). Forty-nine of 74 (66.2%) of the participants pre-intervention gave a correct response about HPV vaccine related adverse effects (“none of the above” in Table 2), while 45/54 (83.3%) of the participants post-intervention answered correctly (p < 0.01). Nearly all participants in both pre-intervention (95.9%) and post-intervention (98.1%) questionnaires answered correctly when asked about the importance of continuing screening for cervical cancer after receiving the HPV vaccine. We found no differences in knowledge on HPV and HPV vaccination when the two institutions were considered and when dental and medical trainees were compared (data not shown; p > 0.05) (Table 3).

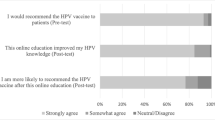

After the educational intervention, 47/54 (87.0%) of all participants strongly agreed that the online education module improved their HPV knowledge (Table 3) . Thirty-seven of 54 (68.5%) strongly agreed that they were more likely to recommend HPV vaccine after the online education intervention. Thirty of 38 (78.9%) strongly agreed that, if allowed by law for dentists, they would be willing to provide HPV vaccines to their patients in their clinics or practices.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that the proposed online HPV educational intervention improved HPV baseline knowledge and HPV vaccines attitudes among dental and medical trainees from two large US-based institutions. The pre-intervention questionnaire responses indicated that the majority of medical and dental trainees were aware of the association between persistent HRHPV infection and cervical and oropharyngeal cancers, but not with penile, anal, vulvar, or vaginal cancers. The pre-intervention responses also indicated that most trainees underestimated the prevalence of HPV infection and were not familiar with the current CDC HPV vaccination schedule. This underlines the importance of including a specific HPV curriculum for both dental and medical trainees. As the care for patients with HPV-related illnesses and cancer required input from providers in different fields of medicine and dentistry, it is imperative that all providers are familiar with the most up-to-date HPV cancer prevention practices.

Similar to our study, Wright et al. identified an important knowledge gap in baseline HPV understanding among dental students across all 4 years at an accredited US dental school [12]. Laitman et al. also reported an educational gap in HPV knowledge among medical students and found that only 50% of medical students surveyed from 10 medical schools in New York State knew about the association of HPV and head and neck cancers [13]. This further demonstrates poor baseline knowledge among trainees.

HPV vaccine recommendations by healthcare providers have shown to be the best predictor of vaccination [7]. Therefore, efforts should be directed to improving HPV and HPV vaccine knowledge, not just among healthcare providers already in medical and dental practices, but also healthcare trainees. Our results showed that with an increase in HPV baseline knowledge, both medical and dental trainees were more receptive to recommending HPV vaccines to their patients. Another study showed that a new curriculum design, focusing on HPV knowledge and HPV vaccine recommendation and communication techniques, increased the perceived likelihood of HPV vaccine recommendation among participating medical students [14]. Similarly, Shukhla et al. reported on the effectiveness of web-based educational modules on HPV among dental students (n = 97) residents (n = 28) and dental hygiene students (n = 17) [15]. Following an online educational intervention, they showed an increase in knowledge about the prevalence of HPV infections, HPV-associated cancers, and diseases that could be prevented with the HPV vaccine.

Dental providers have been recently involved in immunization practices in some States, including the HPV vaccine [16]. However, there is a lack in uniformity in HPV-related curricula. As such, having an online educational intervention to improve HPV education in dental schools could potentially improve HPV vaccination rates. Dental providers have a unique opportunity in regularly seeing patients, especially adolescents, for their routine dental visits and therefore could recommend the HPV vaccine and educate their patients and patients’ parents on the association between high-risk HPV infections and cancer.

The strengths of the study include the inclusion of two large medical and dental schools. This is one of the first studies to look at both medical and dental students and compared respective curricula. In the era of health sciences education that highlights the benefit of interdisciplinary education, this study highlights the future potential for bringing medical and dental students together in HPV education initiatives. The intervention was effective in improving knowledge and willingness to recommend with relatively short time commitment from the participant and is easily implemented in other settings as it is administered online.

There were some limitations with the study. Even though this study was conducted at two large US medical and dental schools, we included a relatively a small sample, and therefore, the results may not be generalizable to all other medical and dental trainees in the country. In the future, we plan to include more dental and medical schools from other States, which will make the results more representative of the current educational scenario on HPV. In addition, the participation in the study was voluntary, and this could have introduced a selection bias for trainees with greater interest in or better baseline knowledge about HPV and HPV vaccination. The study design did not include control group or randomization and therefore we were limited by the extent to which we could extrapolate our conclusions from the results. Without a control group, all participants received the educational intervention and might be subjected to response bias, especially to survey questions in Table 3. Finally, our online intervention did not improve knowledge on who should receive the HPV vaccine among participants. Therefore, we plan on modifying the current online intervention to improve this gap. Future studies should also consider vaccine recommendation techniques, especially for vaccine hesitant parents and patients.

In summary, we found that our proposed online intervention tailored to dental and medical trainees improved baseline HPV and HPV vaccine knowledge and the attitudes towards recommending HPV vaccines to patients. Distance education with synchronic or asynchronous technologies has become common during the recent COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the proposed online tool could be easily adopted to train future healthcare providers and to effectively disseminate HPV-related information and improve current HPV vaccination practices.

Change history

16 January 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-024-02398-w

References

KombeKombe AJ, Li B, Zahid A et al (2021) Epidemiology and burden of human papillomavirus and related diseases, molecular pathogenesis, and vaccine evaluation. Front Public Health 8:552028. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.552028 (Published 2021 Jan 20)

HPV and cancer. National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-and-cancer. Accessed May 24, 2022

HPV-associated cancer statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/index.htm. Published December 13, 2021. Accessed May 24, 2022

How many cancers are linked with HPV each year? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm. Published December 13, 2021. Accessed May 24, 2022

Viens LJ, Henley SJ, Watson M, Markowitz LE, Thomas CC, Thompson TD, Saraiya M (2016) Human papillomavirus–associated cancers — United States, 2008–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65(26):661–666. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6526a1

Increase the proportion of adolescents who get recommended doses of the HPV vaccine - IID‑08 - Healthy People 2030. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/vaccination/increase-proportion-adolescents-who-get-recommended-doses-hpv-vaccine-iid-08. Accessed May 24, 2022

Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, Shah PD, Marciniak MW, Brewer NT (2016) Provider communication and HPV vaccination: the impact of recommendation quality. Vaccine 34(9):1187–1192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.01.023

Paterson P, Meurice F, Stanberry LR, Glismann S, Rosenthal SL, Larson HJ (2016) Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine 34(52):6700–6706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.042

Walker KK, Jackson RD, Sommariva S, Neelamegam M, Desch J (2019) USA dental health providers’ role in HPV vaccine communication and HPV-OPC protection: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother 15(7–8):1863–1869. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2018.1558690

Kernéis S, Jacquet C, Bannay A et al (2017) Vaccine education of medical students: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. Am J Prev Med 53(3):e97–e104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.014

Cancers caused by HPV. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/cancer.html. Published February 28, 2022. Accessed May 24, 2022

Wright M, Pazdernik V, Luebbering C, Davis JM (2021) Dental students’ knowledge and attitudes about human papillomavirus prevention. Vaccines (Basel) 9(8):888. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9080888

Laitman BM, Oliver K, Genden E (2018) Medical student knowledge of human papillomavirus-positive head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 144(4):380–382. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2017.3089

Schnaith AM, Evans EM, Vogt C et al (2018) An innovative medical school curriculum to address human papillomavirus vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine 36(26):3830–3835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.05.014

Shukla A, Chintapalli A, Ahmed MKAB, Welch K, Villa A (2022) Assessing the effectiveness of web-based modules on human papillomavirus among dental and dental hygiene students. J Cancer Educ:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-022-02144-0

Villa A, Chmieliauskaite M, Patton LL (2021) Including vaccinations in the scope of dental practice: the time has come. J Am Dent Assoc 152(3):184–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2020.09.025

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sarah Feldman and Alessandro Villa equally contributed as senior authors.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Thanasuwat, B., Leung, S.O.A., Welch, K. et al. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Education and Knowledge Among Medical and Dental Trainees. J Canc Educ 38, 971–976 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-022-02215-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-022-02215-2