Abstract

Fluxes of methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and respired CO2 were measured with an automated chamber system (SIGMA) over the autumn of 2009 and growing season of 2010 in an undisturbed peatland with a floating carpet of mosses in western Poland. The main goal of our investigation was to deliver estimations of CH4 and N2O emission rates for this unique peatland type in Central Europe. CO2 and CH4 fluxes were also measured using a non-steady-state-flow-through manual chamber systems equipped with infrared gas analyzers and used to validate and adjust results obtained with the SIGMA system. The average methane fluxes for the 2009–2010 (excluding winter) period was 95.4 (±32.4) mg CH4-C m−2 d−1 resulting in a cumulative CH4 emission of 23.4 (±2.4) g CH4-C m−2 day growing season and 29.2 (±3.2) g CH4-C m−2 year−1 for the whole of 2010. The average seasonal N2O fluxes were 13.6 (± 28.2) μg N2O-N m−2 d−1. N2O fluxes were highly variable in time and sign (both uptake and emissions of N2O were observed during the accumulation periods). Maximum estimates of the annual emission rates of N2O were 0.004 g N2O-N m−2 year−1. Methane fluxes correlated significantly with the air and peat temperatures, but they were not dependent on water table depth. The N2O fluxes did not demonstrate a clear response to any environmental variables. Both CH4 and N2O emission rates were in the range of fluxes recorded in pristine peatlands in other climatic zones.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nitrous oxide and methane are the most important greenhouse gases besides carbon dioxide, which are exchanged between terrestrial ecosystems and the atmosphere. The global warming potential (GWP) of CH4 and N2O are 25 and 298 higher than those of carbon dioxide on a 100-year time horizon, respectively (Forster et al. 2007) due to longer residence in the atmosphere and higher radiation absorption efficiency.

Peatlands play an important role in the global C and N cycles, although they cover less than 3 % of the globe’s total land area (Rydin and Jeglum 2006). In general, pristine peatlands with high water levels are considered to be a major source of methane on a global basis (Denman et al. 2007), whereas emissions of nitrous oxide are generally found to be negligible from these ecosystems (Martikainen et al. 1993; Drewer et al. 2010; Lohila et al. 2010). Many peatlands have been degraded over the last century and have been converted to managed agro- or forestry-ecosystems. In western European countries, up to 90 % of peatlands have been altered by different anthropogenic activities (Joosten and Couwenberg 2001). This often results in the peatlands becoming significant sources of CO2 and N2O while CH4 emissions become negligible (e.g. Drösler et al. 2008). Currently, efforts are being undertaken to restore these ecosystems by rewetting or reflooding (e.g. Vasander et al. 2003; Couwenberg et al. 2011), which again should change the greenhouse gas balance significantly (e.g. Augustin and Joosten 2007; Drösler et al. 2008).

The emission rates of CH4 and N2O from peatlands are highly variable at different timescales (e.g. Moore et al. 1990) and spatial scales (Bubier et al. 1993). These features are in part why it is so difficult to measure peatland-scale CH4 and N2O fluxes with high accuracy and why there are such large uncertainties in the global estimations of their emission rates. Methane and N2O flux measurements on wetlands are most often carried out using manual static chambers (e.g. Moore et al. 2011) but the application of micrometeorological techniques such as eddy covariance and relaxed eddy accumulation is becoming more common and is being used to derive year-round measurements of trace gases at the field scale (Rinne et al. 2007; Kowalska et al. 2013). One of the disadvantages of chamber measurements is that they are commonly done manually, thus a frequency of the measurements is rather small and often not sufficient to capture a number of transient fluxes that occur within hours and are related to ebullition (Lai 2009). What is more, manual chamber measurements introduce many artifacts that may influence measured fluxes significantly (Davidson et al. 2002; Christiansen et al. 2011; Juszczak 2013). Considering the above, the automated chambers are usually deployed in order to do analyses several times per day.

There are many studies on CH4 and N2O emissions from pristine peatlands of Scandinavia, Canada, Siberia, and tropical regions (e.g. Martikainen et al. 1993; Moore 1994; Alm et al. 1999; Huttunen et al. 2003; Drewer et al. 2010; Lohila et al. 2010; Sachs et al. 2010; Moore et al. 2011). However, to our knowledge, there is no information about the long term N2O and CH4 fluxes from pristine fen peatlands under the temperate climate of western and central Europe. In order to correctly assess the greenhouse gas fluxes for peatlands in western and central Europe and how they may change in the future, there is an urgent need to quantify greenhouse gases fluxes at the relatively rare undisturbed peatlands in this region.

The main goal of our investigation was to deliver estimates of CH4 and N2O emission rates for a pristine fen with a floating carpet of mosses in western Poland. We hypothesize that emissions of these greenhouse gases will be higher than those estimated for pristine peatland of the boreal European region mainly due to higher average temperature and longer growing season. Fluxes of CH4, N2O, and respired CO2 were measured with a new automated chamber system and two manual chamber systems in autumn 2009 and during the growing season of 2010. The relationships between measured fluxes and environmental variables driving the emission processes are investigated and used to develop simple regression models. The models are used to estimate cumulative emissions of these greenhouse gases over the growing season and for an entire year.

Materials and Methods

Study Site

The Rzecin wetland (POLWET) is a large (87 ha) mesotrophic, geogenous, terrestrialisation peatland, located in the middle of the Notecka Primeval Forest in Western Poland (52°45′ N latitude, 16°18′ E longitude, 54 m a.s.l.). It is surrounded mostly by extensively used grasslands and some very small crop fields. In the middle of the peatland, there is a 70-cm thick floating carpet of peat-substrate overgrown mostly by mosses underlain by a free water layer and saturated sediment. The distance between the peatland surface and the mineral bedrock increases from 2 m at the periphery to 11 m towards the center of the peatland. In the eastern part of the peatland, there is a shallow ~ 16 ha decaying lake, which has been overgrown by Typha latifolia L., and Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. The vegetation of the peatland is dominated by: Sphagnum spp., Dicranum spp., Carex spp., P. australis, T. latifolia, Oxycoccus palustris Pers., Drosera rotundifolia L., Potentilla palustris L., Ranunculus acris L. and Menyanthes trifoliata L. (Chojnicki et al. 2010; Juszczak et al. 2012). The peat substrate is a Limnic Hemic Floatic Ombric Rheic Histosol (Epidystric) according to FAO 2006 classification.

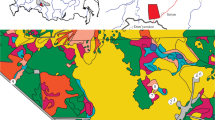

Measurements of CH4 and N2O fluxes were carried out at one microsite located in the middle of the peatland, next to the wooden boardwalk ca. 400 m long, which connect the eddy covariance tower and weather station with the edge of the wetland (Fig. 1). This microsite is dominated by Carex spp., Oxycoccus palustris Pers. and Drosera rotundifolia L. with a nearly continuous cover of Sphagnum teres (Schmp.) Ångstr.. The Leaf Area Index (LAI) of the vascular plants at the site was 1.8 m2 m−2 (Juszczak et al. 2013). Ash content and degree of peat decomposition at a depth of 20 cm in 2012 was 7.6 % and 13.3 %, respectively (Juszczak et al. 2013). Average C and N content of the peat at this location did not exceed 420 and 14 mg g−1 of dry peat mass respectively in the peat at 25–45 cm depth, while the average C:N ratio reach at this depth is 36. Based on random analysis of peat pore water, we found 1 mg NH4 +-N l−1 and <0.01 mg NO3 −-N l−1 (D. Zak, personal communication 2010). The average wet and dry deposition of N for the years 2008–2010 did not exceed 4 kg N ha−1 year−1 (unpublished data) and 7.5 kg N ha−1 year−1 (Flechard et al. 2011), respectively. These findings suggest the Rzecin wetland site is a N limited ecosystem.

Location of the Rzecin peatland and trace gases measurement microsites (modified after Juszczak et al. 2013)

Manual and automated flux measurements of CH4, N2O, and CO2 were carried out at three microsites located only a few meters from one another (Fig. 1). The automated chambers were established in 2009 near where manual chamber CH4 and CO2 fluxes were measured since 2005 and 2007, respectively (Chojnicki et al. 2007; Juszczak et al. 2013).

Flux Measurements

Fluxes of CH4, N2O and additional CO2 (ecosystem respiration, R eco , as the sum of autotrophic and heterotrophic respiration) were measured by means of an automated accumulation chamber system, the System for Inert Gas Monitoring by Accumulation (SIGMA), according to methodology described by Ambus et al. 2010. These chambers were operated from October 2009 until September 2010, excluding a 14 week winter period.

SIGMA chambers were originally developed to carry out automated measurements of trace gases fluxes in grassland ecosystems with short vegetation and they were satisfactorily validated under such conditions (Ambus et al. 2010). However, they have not been validated yet under peatland conditions. In order to validate the SIGMA chambers, additional measurements of CH4 and CO2 fluxes were made using two non-steady-state flow-through manual chamber systems (Livingston and Hutchinson 1995). These measurements were made every 2–3 weeks from June through the end of October 2010. An additional measurement campaign was carried out in February 2011 to measure CH4 fluxes in winter.

Automated Chamber

The SIGMA system was developed by Ambus et al. 2010 as an inexpensive and easy-to-handle alternative to other more sophisticated and infrastructure-demanding automated systems. There were three SIGMA systems used at our site as replicates and all of them were located within a few meters of one another in a protected area surrounded by a fence. Each individual chamber system consisted of a stainless steel frame (1.85 × 0.78 × 0.3 m), which was in our case mounted on the wooden frame placed on the peat surface to counteract a possible submergence of the thin chamber frame into the peat. The chamber itself was made from white non-transparent PVC with dimensions of 0.70 × 0.70 × 0.10 m. This relatively large chamber surface area (4,900 cm2) provided an opportunity to integrate small-scale microtopographical and plant community variations that is often not possible with smaller and more typical chamber systems. A white PVC collar was inserted into the peat at the depth of 15 cm. The chamber was unvented and there were no fans installed to the chamber headspace. To facilitate the opening and closing, the chamber was mounted on sigmoid-shaped bars. To close, the chamber moved horizontally from the ‘parking’ position followed by a downward movement to secure the chamber onto the collar. Silicone tubing attached to lower rim sealed the chamber. A more detailed technical description of the chamber and its operation is described by Ambus et al. 2010.

During a flux measurement, the SIGMA chamber collected an exact volume of air from the chamber headspace in three FlexFoil Grab Bags (SKC, Blandford Forum, Dorset, UK) at 10 min, 48 min and 125 min after the closure of the chamber, after which, the chamber lid lifted off the collar and returned to its ‘parking’ position. Tubes (inlet and outlet) were installed to the upper part of the collar in the opposite corners. They were flushed 10 min before the first sample was taken and 2 min before the second and third samples. The amount of sample collected depended on a flow rate (70 ml/min), sample time (30 s) and could be adjusted by the metering valve. The flow rate into each bag was controlled by an ultrafine metering valve (HOKE Mili-Mite, Circor Instr., UK), while a flushing of the tubes was provided by a micro diaphragm pump at maximum 500 ml/min (KNF Neuberger, Germany). The chamber was closed three times per day at 9:00 am, 1:00 pm and 6:00 pm for a total collection of 105 ml of air in each bag. The 3 L bags allowed the SIGMA chambers to operate for a maximum of 28 days. In our case, the length of the accumulation period varied from 14 to 28 days, but in most cases the length of this period did not exceed 22 days. After this time the bags were exchanged. The air from filled bags was evacuated to vacuumed glass bottles of 100 ml (Schott Duran) and then transported within the five next days to the Leibniz Centre for Agricultural Landscape Research (ZALF) laboratory for gas chromatography analyses. The samples were analyzed within 5 days of delivery. In total, gas sample storage times did not exceed 38 days. The trace gases (N2O, CH4, CO2) concentrations were measured by a Shimadzu GC-14A gas chromatograph equipped with an electron capture detector for N2O and CO2 and flame ionization detector for CH4 according to Loftfield et al. (1997). The detection limit of the gas chromatograph for CH4 is < 0.01 μl l−1, for CO2 < 6 μl l−1, and for N2O 0.003 μl l−1 (Loftfield et al. 1997).

In order to protect the SIGMA chambers against freezing, the control unit was equipped with a thermostat, which shut off the system once the air temperature dropped below 5 °C. Thus, measurements could be made only during warm conditions and thus limited the number of accumulation periods and did not allow for winter measurements. There were in total 11 accumulation periods, four in 2009 and seven in 2010. In 2009, the measurements began on 1st of October and finished the 11th of December (71 days). In 2010, measurements were carried out between 25th of March and 9th of September (168 days).

Manual Chambers

Manual chamber measurements took place at sites 7 m east of the SIGMA chambers (Fig. 1). CH4 flux measurements were carried out with the round chamber system no. 16 described by Pihlatie et al. (2013) and by Christiansen et al. (2011). The chamber was made from opaque white PVC and has the shape of a truncated cone 0.41 m in height with a 0.21 m2 surface area and 0.065 m3 volume. The chamber was sealed to the collar using a water-filled groove. Five PVC collars were installed in 2005 (Fig. 1) and inserted 10 cm into the peat. The chamber headspace was mixed by one fan installed horizontally at 3/4 height of the chamber. This was a standard 1.2 W computer fan with 3,000 spins min−1. The change in headspace CH4 concentration over a 15 min closure period was measured by a fast methane gas analyser (DLT-100, Los Gatos Research, Inc, USA). The internal pump of the analyser was used for pumping the air from the chamber headspace to the analyser cell and back at a flow rate of 0.3 L min−1. The CH4 concentration changes were recorded at 1 Hz. There were five measurement campaigns in 2010 and one in February 2011. During each campaign, measurements were repeated two times at five collars resulting in 60 flux measurements for this analysis.

CO2 fluxes were measured on-site with a non-transparent rectangular chamber (a non-steady-state flow-through chamber system according to Livingston and Hutchinson 1995) equipped with an infrared CO2 analyzer using the methodology described in Juszczak et al. 2012, 2013. The chamber (77 cm × 77 cm × 50 cm) was made from 3 mm thick white (non-transparent) PVC to ensure dark conditions and had a total volume of 0.3 m3. The chamber was equipped with two small fans (1.2 W) to effectively mix the air in the chamber headspace during measurements. The chamber was fixed onto the collars by two elastic belts connecting the top of the chamber and the base of the frame. A rubber gasket at the base of the chamber ensured an airtight seal. Air was circulated at approximately 2.5 L min−1 between the chamber and a portable control box containing an infrared gas analyzer (LI-820, LICOR, USA), which measured CO2 concentration in the air connected to a bypass flowing at 0.6 L min−1. During a single flux measurement, the chamber remained in place between 150 s in summer to 240 s in winter. The concentration and air and peat temperature readings were recorded at 5-second intervals on a data logger (CR-1000, Campbell Sci., USA) installed in a portable control box. Measurement campaigns were carried out once per month in the years overlapping the SIGMA chamber operation.

Flux Calculations

In the case of the SIGMA chambers it was assumed that the target gas concentration measured at three sampling bags revealed the average concentration of chamber headspace at three successive time-steps aggregated over multiple cycles (after Ambus et al. 2010). Based on the measured average concentrations, the average trace gas fluxes over multiple chamber enclosure cycles were calculated by using the simple linear approach (Eq. 1).

The trace gas fluxes determined in the manual chambers were calculated with the linear method based on the gas concentration change in the chamber headspace over closure time. The CH4 fluxes were determined based on the first 3–6 min, while CO2 fluxes were determined using the first minute of data, when the gas concentration changes are greatest and are assumed to be least disturbed by the chamber deployment. When there were initial disturbances of the gas concentration, as described by Christiansen et al. (2011), this data was excluded and the fluxes were calculated based on the steepest part of the regression curve showing the gas concentration development over time. Trace gas fluxes were calculated from:

where F CO2-C , CH4-C, N2O-N are the CO2, CH4, and N2O fluxes [g CO2-C m−2 day−1, μg · CH4-C · m−2 · h−1, μg · N2O-N m−2 · h−1 ], M is the molar mass [g · mol−1] of the gas, P is the atmospheric pressure [Pa], δv represents trace gases concentration changes in the chamber headspace over the closure time [ppm(v)], V is the total volume of the chamber headspace and the collar [m3], R is the gas constant [m3 · Pa · K−1 · mol−1], T is the air temperature in the chamber [K], t is the closure time [h] and A is the chamber area [m2], respectively.

Validation of the SIGMA Chambers

The SIGMA chamber fluxes were validated using the two manual dynamic flow-through chamber systems described above for the measurement of CH4 and CO2. We calculated average and cumulative CH4 and CO2 fluxes to match the 2009–2010 SIGMA accumulation periods. A linear relationship between manual CH4 flux measurements and 5 cm peat temperature (with the smallest RMSE) was used to calculate daily CH4 emissions. For CO2 fluxes, the Lloyd and Taylor (1994) respiration model was parameterized for each individual CO2 measurement campaign (Michalak-Galczewska 2011). Using these model parameters we simulated 30 min R eco and used these to calculate the average and cumulative R eco fluxes for the periods when the SIGMA chambers were operated.

Measurements of Site-Specific Environmental Variables

Air and peat temperatures (T) as well as water table depth (WTD) were recorded as 30 min averages on the weather station located ca. 100 m north from the chamber measurement site. Manual measurements of WTD, pH and electrical conductivity (EC) were carried out every 3–4 weeks in wells installed at the CO2 chamber microsite (after Michalak-Galczewska 2011) located a few meters east from the site where the SIGMA chambers were located. In all cases WTD was measured relative to the peat surface. The variations in surface elevation were not measured. pH and EC were measured with the pH/conductometer (CPC-411, Elmetron, Poland). Based on manually and automatically measured WTD levels, we simulate the collar specific daily WTD. These values were then used to calculate the average WTD for the SIGMA accumulation periods.

Regression Models

In order to identify statistically significant explanatory variables for the measured CH4 and N2O fluxes we developed a Pearson correlation matrix using all measured ancillary data for the 11 averaging periods. For the CH4 fluxes, 6 daily average fluxes (from 2 replicate measurements/day) determined with the manual chamber in 2010–2011 were combined with the SIGMA fluxes and analyzed as one dataset (n = 17). Additionally, we did the same analysis separately for the CH4 fluxes measured by manual chambers (using each flux measurement separately such that n = 6 dates × 2 replicates = 12). For those variables that have the highest explanatory power we developed linear and exponential regression models in the stepwise procedure. The start point was a simple linear regression:

and then we added other significantly correlated variables in a stepwise procedure:

The significance of the model parameters was verified at each step, and only those which were significant (α < 0.05) were left in the model. An exponential regression model was also developed:

In addition to coefficients of variation, goodness-of-fit parameters normalized root mean square error (NRMSE) and root mean square error (RMSE) were calculated to assess the regressions.

Cumulative CH4 fluxes were calculated over the autumn 2009, growing season 2010 (25 March – 31 October) and for the whole of 2010 by integrating the modeled daily flux time series. Two estimates of the cumulative fluxes were calculated with one estimate based on the regressions determined for the combined SIGMA and manual chamber dataset and the other based on only the manual chamber dataset. The uncertainty of the cumulative fluxes was assessed by error propagation using the NRMSE of the regression models.

Results

Weather Characteristics

As expected, average air and peat temperatures were substantially warmer during the growing season than in the autumn period (Table 1). Although average WTD did not differ between these two periods there was much more temporal variability during the growing season than in the autumn (Fig. 2). During the entire measurement period, WTD remained within ~ 8 cm of the surface except for a period during July 2010 at the end of a 2 month dry spell when air temperatures also peaked (Fig. 2). pH remained relatively constant through the measurement period varying only from 5.9 to 6.7 (Table 1). There were greater temporal variations in electrical conductivity (EC) with the autumn period having nearly twice the EC as the 2010 growing season.

Validation and Correction of the SIGMA Flux Data

The average accumulation period-specific CO2 and CH4 fluxes measured with the SIGMA chambers were compared with average fluxes based on regressions between temperature and fluxes measured with the manual chamber system. Both the SIGMA average R eco and CH4 fluxes were lower by 40–46 % than the fluxes based on the manual chamber measurements (Fig. 3). The reference respiration (R ref ) estimated from the regressions between CO2 effluxes and peat temperature based on the Lloyd and Taylor (1994) respiration model is also underestimated by 34 % (Fig. 4). Considering these differences we calculated a correction factor of 1.67 for the SIGMA CH4 fluxes by dividing the average CH4 flux based on the manual chamber measurements (86.3 mg CH4-C · m−2 · d−1) by the average CH4 effluxes measured with SIGMA chambers (51.8 mg CH4-C · m−2 · d−1). We assumed that the rate of N2O fluxes underestimation would be the same and the same correction factor was applied for these fluxes. All the flux data from the SIGMA chambers are presented with these corrections from this point on.

The average R eco fluxes and peat temperature at 5 cm depth specific for each SIGMA accumulation period. Gray circles refer to the average R eco fluxes measured by the SIGMA chambers, while black triangles refer to fluxes modeled based on the manual chamber measurements. The associated Lloyd and Taylor (1994) exponential function is shown for SIGMA (dashed gray line) and manual (black solid line) chamber fluxes. Differences between Lloyd and Taylor (1994) respiration model parameters: R ref – reference respiration at 10 °C; E o – activation energy, are shown on the graph

Fluxes of Trace Gases and Their Relationships with Environmental Variables

The average corrected SIGMA system CH4 fluxes were 69.5 (±13.9) mg CH4-C · m−2 · d−1 and 104.1 (±32.5) mg CH4-C · m−2 · d−1 in the autumn 2009 and growing season of 2010, respectively. The highest CH4 fluxes were measured in the warmest period between 28th of July and 18th of August 2010, which followed the heavy rainfall near the end of July (Figs. 2a and 5a). The average CH4 effluxes in this period was 164 (±25.4) mg CH4-C · m−2 · d−1 (Fig. 5b). The lowest fluxes were measured in February 2011 when emissions dropped to 13.5 (±10.2) mg CH4-C · m−2 · d−1.

Total precipitation and average WTD for each individual SIGMA accumulation period of 2009 and 2010 (black squares) and for days when manual chamber measurements were conducted (gray squares) (a). Note that the manual measurements were made on dates without rainfall. Measured average fluxes of methane (b) and nitrous oxide (c) for 2009–2010. The average CH4 fluxes measured by SIGMA chambers (for each individual accumulation period) are in light-gray, while the average fluxes measured by manual chambers are in dark-gray. Black error bars indicate standard deviation of the replicate measurements within a microsite, providing information about spatial variability

Average CH4 fluxes were positively correlated with air and 5 cm peat temperatures and both relationships were significant (p < 0.05 if all average fluxes are considered and p < 0.001 if only fluxes measured by manual chambers are considered) (Table 2). The correlation between CH4 fluxes and pH was negative and was also significant at p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, for the combined CH4 flux dataset and for the manually measured CH4 fluxes, respectively. Although we did not find a significant relationship between CH4 fluxes from the SIGMA system and WTD, this relationship was significant for the manually measured CH4 fluxes (p < 0.001).

The average N2O fluxes over the measurement period were variable with both positive and negative fluxes however all were very small and close to the detection limits of the gas chromatograph. Average corrected N2O fluxes were 6.37 (±26.67) μg N2O-N · m−2 · d−1 and 17.76 (±30.26) μg N2O-N · m−2 · d−1 for the 2009 autumn period and the 2010 growing season, respectively. No significant relationships between N2O fluxes and environmental variables were found (Table 2) and therefore no further analyses were carried out.

Regression Models and Cumulative Trace Gas Fluxes

Based on the results in Table 2, simple linear and exponential regression models for the SIGMA CH4 fluxes were developed using air temperature as the predictor variable (Table 3). For the manually measured CH4 flux dataset, air and peat temperature and WTD were significantly correlated with CH4 flux (Table 2) and the stepwise regression model (Eq. 3) was investigated. However, the simple linear model with only air temperature as a predictor variable resulted in the highest explanatory power, the smallest error and the smallest uncertainty of the estimated cumulative CH4 fluxes.

The cumulative CH4 fluxes estimated from these various models ranges from 4.4 to 6.8 g CH4-C m−2, from 21.6 to 27.4 g CH4-C m−2, and from 25.4 to 33.5 g CH4-C m−2 for the autumn of 2009, the 2010 growing season and through all of 2010, respectively (Table 4). For the 3 weeks of June 2010 when the SIGMA chamber was not working correctly, we used the average CH4 flux (118.45 mg CH4-C · m−2 · d−1) computed using the linear regression model in order to calculate the seasonal and annual flux.

The cumulative N2O fluxes were calculated based on the average corrected N2O fluxes aggregated for each accumulation period (n = 11) and were 0.5 and 3.5 mg N 2 O-N m −2 for the autumn of 2009 and the 2010 growing season, respectively. For the period between 9th to 30th of June 2010, when SIGMA chambers did not operate properly, N2O flux was calculate as the average of fluxes measured in the periods before and after to calculate seasonal cumulative N2O flux. If we assume, after Alm et al. (1999) that the wintertime fluxes of N2O on undisturbed peatlands are close to zero, than the yearly accumulated N2O fluxes at our site does not exceed 41 g N2O-N · ha−1 · year−1.

Discussion

Applicability of SIGMA System for Automated Measurements of CH4 and N2O Fluxes

We found the SIGMA system to be a low-cost option for producing estimates of trace gas fluxes from our remote peatland site. However, our results suggest this system (with our setup) may substantially underestimate actual fluxes and with 2–3 weeks accumulation periods, short-term variations in fluxes and their controls (e.g. due to rapid changes in environmental conditions e.g. thawing, rain events, drought periods, etc.) are not detectable. In addition, the SIGMA system is not suitable for wintertime measurements. Thus, to get reliable annual flux estimates for the site, these systems would need to be supported by the other measuring techniques that could operate whole over the year.

Our determination that the SIGMA system underestimated CO2 and CH4 emissions by about 40 % is within the range of underestimation for CH4 fluxes measured using many static chamber systems in a laboratory study by Pihlatie et al. (2013). On average, the chamber systems in that study underestimated fluxes by 33 % when a linear flux calculation was used. The underestimation rate was greater for chambers with heights less than 0.22 cm. In our study, the SIGMA chamber (height = 10 cm) was considerably shorter than our manual chambers used to measure CH4 and CO2 fluxes (height = 0.41 m and 0.50 m, respectively). What is more, the closure time was much longer in SIGMA chambers than in manual one, hence with the 125 min closure time and non-linear development of gases concentration in the chamber headspace, the linearly calculated fluxes may be underestimated. Consequently, it is quite possible that some of the discrepancy between the SIGMA fluxes and manual fluxes might be related to these technical differences although it is important to note that the manual chamber method may also underestimate the actual flux. However, differences between the two systems may also be related to the small number of discreet measurements made with the manual chamber system and the method used to temporally scale these to daily estimates of CO2 and CH4 fluxes. Ambus et al. (2010) tested the SIGMA chambers under field conditions at different sites (grassland and cropland) and compared them with conventional autochambers, where the chamber was closed several times per day. They found no consistent difference between those two systems. Depending on the site, the N2O fluxes were under- or overestimated in relation to fluxes measured by the conventional autochamber. When these two systems were compared simultaneously, the N2O fluxes agreed within ±12 %.

Environmental Controls of Fluxes

The relationship between CH4 and N2O fluxes and environmental variables is very complex (e.g. Le Mer and Roger 2001; Lai 2009; Drewer et al. 2010; Bell et al. 2012; Rees et al. 2013). At our site, the single parameter with the highest explanatory power for the observed N2O and CH4 fluxes was air temperature although it was not significant for N2O fluxes. Microbial processes drive the production of both gases in peat and the rates of microbial activity are controlled by temperature (e.g. Dunfield et al. 1993; Crill et al. 1994). Lohila et al. (2010) found air temperature was the best predictor of N2O fluxes measured by an automated chamber system in an N-limited boreal fen. Methane fluxes have been found to relate to variations in air temperature (e.g. Treat et al. 2007) or surface temperature (e.g. Hargreaves et al. 2001; Sachs et al. 2010) or peat temperature at different depths (e.g. Huttunen et al. 2003) in other peatlands. In addition to enhancing microbial-mediated CH4 production, increasing temperature may enhance CH4 transport from peatlands by promoting ebullition and plant-mediated transport (Lai 2009).

Beside temperature many authors have indicated that WTD is a good estimator for seasonal CH4 and N2O emissions from peatlands. In our study, average N2O fluxes were not significantly correlated to WTD. This is in contrast to other studies that have found a decrease in N2O emissions when WTD was closer to the peat surface as the main product of microbially-mediated denitrification may be N2 instead of N2O in peatland under anoxic conditions (Well et al. 2003; Rückauf et al. 2004; Lohila et al. 2010). The negative N2O fluxes observed at our site under relatively wet conditions (WTD did not drop below 15.6 cm from the surface) indicate that N2O can be taken up from the atmosphere, induced by the N-limited situation of our wetland. Other researchers have already indicated that under such conditions, denitrification may be responsible for N2O uptake from the atmosphere in peatlands (Chapuis-Lardy et al. 2007; Lohila et al. 2010; Kolb and Horn 2012). On the other hand, it is well known that rapid waterlogging of the peat due to a precipitation event, particularly after 2–3 weeks of dry conditions may promote subsurface N2O production and increase emissions of N2O within several hours of the event (Jǿrgensen and Elberling 2012). Unfortunately, our measurement system was not able to detect such phenomena. Small N2O fluxes and relatively large spatial variations for each averaging period made it difficult to clearly identify significant environmental controls on N2O fluxes.

The relationship between CH4 fluxes and WTD at our wetland was also not as clear as in other studies. Most researchers found increasing CH4 emissions with rising WTD (e.g. Huttunen et al. 2003; Sachs et al. 2010). In our study, WTD was significantly negatively correlated with the CH4 fluxes derived from the manual chamber measurements but insignificantly correlated to the combined SIGMA and manual chamber dataset. Others have suggested this result may be explained in part by small variations in WTD over the measurement period (Shannon and White 1994). At our peatland, the floating peat mat is expected to move as WTD varies and may explain the relatively small range in growing season WTD (~16 cm) despite nearly 6 weeks with little rainfall in June and July 2010. Nevertheless, in a situation such as ours where WTD drops as air and peat temperatures increase, enhanced CH4 production rates and ebullition are likely caused by higher peat temperatures and reduced hydrostatic pressure (Moore et al. 1990; Treat et al. 2007). In our study, this effect appears to be more pronounced than any increase in CH4 oxidation rates as the peat becomes more aerated (Bubier 1995; Sundh et al. 1995). The relationship between CH4 fluxes and WTD may be also complicated by lagged responses to varying WTD. For example, Suyker et al. (1996) reported a rise in CH4 emissions after a sharp increase in WTD but with a 12 day lag. As with the N2O fluxes, the large integrating times may also mask both immediate or lagged WTD responses.

The relationship between CH4 fluxes and WTD is further complicated by the presence of vegetation with aerenchymous tissue (Whalen 2005). In the case of this study WTD did not drop below −16 cm over the whole measuring period, thus the rooting systems of sedges, which are reported to grow down even to 230 cm (Saarinen 1996), can effectively transport methane from depth to the atmosphere, even during the driest periods. Hence, this transport mechanism may bypass the aerobic peat where CH4 can be oxidized and maintain or enhance CH4 emissions even during the periods with lowest WTD. In the case of our peatland, the presence of Carex sp. may be another reason for higher CH4 emissions as WTD decreased.

Comparison with Other Sites

Methane

The average corrected CH4 fluxes calculated for the 2009–2010 (excluding winter) measurement period at our site was 95.4 (±32.4) mg CH4-C · m−2 · d−1. This corresponds well to the average daily CH4 emissions (93 mgCH4-C · m−2 · d−1) from a number of peatlands of the southern and middle boreal zones of Finland where the average WTD level was −10 cm (Nykänen et al. 1998; Huttunen et al. 2003) but it is more than two times higher than the average annual CH4 fluxes estimated by Cao et al. (1998) for high-latitude (50–60°N) peatlands (38.25 mg CH4-C · m−2 · d−1) based on process-based modeling.

The total cumulative CH4 fluxes at our site reached 19.1 (±1.9) g CH4-C · m−2 · year−1 for the growing season and 29.2 (±3.2) g CH4-C · m−2 · year−1 for 2010 and fell within the range of the average CH4 emissions (0.09 to 36 g CH4-C · m−2 · year−1) estimated for 45 natural minerotrophic peatlands (36 from Europe) by Saarnio et al. (2009). However, our rates are more than 40 % greater than those estimated for European and Asian minerotrophic natural peatlands where average emissions were 12.5 g CH4-C · m−2 · year−1 and 16 g CH4-C · m−2 · year−1 for the growing season and the whole year, respectively (Huttunen et al. 2003).

Methane emission rates are recognized to have great spatial heterogeneity as they are highly dependent on plant community types. For example, Drösler (2005) found very high spatial variability in CH4 fluxes among different vegetation microsites of the “Kendlmühlfilze”, a natural temperate bog peatland in southern Bavaria, Germany where average cumulative annual CH4 fluxes varied from 5.4 to 38.2 g CH4-C · m−2 · year−1. At our peatland there are also more than 30 plant communities (Juszczak et al. 2013) but our measurements were carried out at a microsite located in the middle of the peatland, which is dominated by Carex spp., Oxycoccus palustris Pers. and Sphagnum teres (Schmp.) Ångstr. Therefore, a realistic comparison of CH4 source strength of our peatland as a whole with that of other sites would require comprehensive measurements of the other plant communities best achieved by using a combination of eddy covariance and different chamber techniques.

Nitrous Oxide

The average seasonal corrected nitrous oxide flux calculated for the overall measuring period of 2009–2010 (excluding winter period) reach 13.6 ± 28.2 μg N2O-N · m−2 · d−1 and was within the range of the average annual fluxes estimated by Lohila et al. (2010) for Lompolojänkkä peatland in Finland (from 0 to 288 μg N2O-N · m−2 · d−1). Overall, N2O fluxes estimated for boreal peatlands in Finland, which cover different nutrient status, varied from −19.2 to 127 μg N2O-N · m−2 · d−1 (Regina et al. 1996). If we assume, after Alm et al. (1999) that the wintertime fluxes of N2O on virgin peatlands are close to zero, than the yearly accumulated N2O fluxes at our site does not exceed 41 g N2O-N · ha · year−1. This value is very close to Martikainen et al. (1993) estimations. According to this review study, the average yearly N2O emission rates does not exceed 40 g N2O-N · ha · year−1 at the minerotrophic virgin peatland sites. This value is negligible, if we compare it to the N2O fluxes from drained peatlands, where the yearly emission rates can reach even 14 kg N2O-N · ha · year−1 (e.g. Augustin et al. 1998). Although relatively few data are available on the N2O flux from pristine peatlands, studies show very similar low emissions (e.g. Martikainen et al. 1993; Regina et al. 1996). N2O fluxes from ombrotrophic (nutrient-poor) bogs are generally much smaller (often negligible) than those measured in minerotrophic nutrient-reach fens (e.g. Regina et al. 1996). For example, in the Hudson Bay lowland the annual flux rate ranged from −2.4 g N2O-N · ha · year−1 in a treed bog to 50.3 g N2O-N · ha · year−1 in an open fen (Schiller and Hastie 1994).

Conclusions

In this study we hypothesized that emissions of CH4 and N2O at the pristine Rzecin peatland in central Europe would be higher than those from pristine boreal peatlands in Europe and Canada mainly due to higher average temperature and a longer growing season. However, the Rzecin N2O fluxes were very low and were similar to those measured at pristine peatlands in boreal regions. There was large variation in CH4 emissions among our chamber sites suggesting that a more accurate estimate of CH4 from the Rzecin peatland would require additional chamber measurements within the other dominant vegetation types and ideally be supported by ecosystem-scale measurements using the eddy covariance approach for example.

However, methane emissions did correlate well with temperature and were larger than at some boreal peatlands presumably due to the warmer climate and longer growing season in Poland. Larger CH4 emissions were also likely supported by the presence of sedges acting as conduits and the adjustment of a floating moss carpet to variations in WTD. Nevertheless, our values still fell within the very broad range of fluxes observed for northern pristine peatlands.

References

Alm J, Saarnio S, Nykänen H, Silvola J, Martikainen PJ (1999) Winter CO2, CH4 and N2O fluxes on some natural and drained boreal peatlands. Biogeochemistry 44:163–186

Ambus P, Skiba U, Drewer J, Jones SK, Carter MS, Albert KR, Sutton MA (2010) Development of an accumulation-based system for cost-effective chamber measurements of inert trace gas fluxes. European Journal of Soil Science 61:785–792

Augustin J, Joosten H (2007) Peatland rewetting and the greenhouse effect. International Conservation Group Newsletter 3:29–30

Augustin J, Merbach W, Rogasik J (1998) Factors influencing nitrous oxide and methane emissions from minerotrofic fens in northeast Germany. Biology and Fertility of Soils 28:1–4

Bell MJ, Jones E, Smith J, Smith P, Yeluripati J, Augustin J, Juszczak R, Olejnik J, Sommer M (2012) Simulation of soil nitrogen, nitrous oxide emissions and mitigation scenarios at 3 European cropland sites using the ECOSSE model. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 92:161–181

Bubier JL (1995) The relationship of vegetation to methane emission and hydrochemical gradients in northern peatlands. Journal of Ecology 83(3):403–420

Bubier JL, Costello A, Moore TR, Roulet NT, Savage K (1993) Microtopography and methane flux in boreal peatlands, northern Ontario, Canada. Canadian Journal of Botany 71:1056–1063

Cao M, Gregson K, Marshall S (1998) Global methane emission from wetlands and its sensitivity to climate change. Atmospheric Environment 32:3293–3299

Chapuis-Lardy L, Wrage N, Metay A, Chotte J-L, Bernoux M (2007) Soils, a sink for N2O? A review. Global Change Biology 13:1–17

Chojnicki BH, Urbaniak M, Józefczyk D, Augustin J (2007) Measurement of gas and heat fluxes a Rzecin wetland. In: Okruszko T (ed) Wetlands: monitoring, modeling and management. Taylor and Francis Group, London, pp 125–131

Chojnicki BH, Michalak M, Acosta M, Juszczak R, Augustin J, Droesler M, Olejnik J (2010) Measurements of carbon dioxide fluxes by chamber method at Rzecin wetland ecosystem in Poland. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies 19(2):283–291

Christiansen JR, Korhonen J, Juszczak R, Giebels M, Pihlatie M (2011) Assessing the effects of chamber placement, manual sampling and headspace mixing on CH4 fluxes in a laboratory experiment. Plant and Soil 343:171–185

Couwenberg J, Thiele A, Tanneberger F, Augustin J, Bärisch S, Dubovik D, Liashchynskaya N, Michaelis D, Minke M, Skuratovich A, Joosten H (2011) Assessing greenhouse gas emissions from peatlands using vegetation as a proxy. Hydrobiologia 674:67–89

Crill PM, Martikainen PJ, Nykänen H, Silvola J (1994) Temperature and N fertilization effects on methane oxidation in a drained peatland soil. Soil Biology & Biogeochemistry 26:1331–1339

Davidson EA, Savage K, Verchot LV, Navarro R (2002) Minimizing artifacts and biases in chamber-based measurements of soil respiration. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 113(1):21–37

Denman KL et al (2007) Couplings between changes in the climate system and biogeochemistry. In: Solomon S et al (eds) Climate change 2007: the physical science basis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 539–544

Drewer J, Lohila A, Aurela M, Laurila T, Minkkinen K, Penttilä T, Dinsmore KJ, McKenzie RM, Helfter C, Flechard C, Sutton MA, Skiba UM (2010) Comparison of greenhouse gas fluxes and nitrogen budgets from an ombrotrophic bog in Scotland and a minerotrophic sedge fen in Finland. European Journal of Soil Science 61(5):640–650

Drösler M (2005) Trace gas exchange and climatic relevance of bog ecosystem, Southern Germany. PhD Dissertation, Lehrstuhl für Vegetationsokologie, Department für Ökologie, Technischen Universität München

Drösler M, Freibauer A, Christensen TR, Friborg T (2008) Observations and status of peatland greenhouse gas emissions in Europe. In: Dolman AJ, Freibauer A, Valentini R (ed) The continental-scale greenhouse gas balance of Europe. Ecological Studies 203, Springer, pp 243–261

Dunfield P, Knowles R, Dumont R, Moore TR (1993) Methane production and consumption in temperate and subarctic peat soils: response to temperature and pH. Soil Biology & Biogeochemistry 25:321–326

Flechard CR, Nemitz E, Smith RI, Fowler D, Vermeulen AT, Bleeker A, Erisman JW, Simpson D, Zhang L, Tang YS, Sutton MA (2011) Dry deposition of reactive nitrogen to European ecosystems: a comparison of inferential models across the NitroEurope network. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 11:2703–2728

Forster P, Ramaswamy V, Artaxo P, Berntsen T, Betts R, Fahey DW et al (2007) Changes in atmospheric constituents and in radiative forcing. In: Solomon S, Qin D, Manning M, Chen Z, Marquis M, Averyt KB et al (eds) Climate change 2007: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 129–234

Hargreaves K, Fowler D, Pitcairn C, Aurela M (2001) Annual methane emission from Finnish mires estimated from eddy covariance campaign measurements. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 70:203–213

Huttunen JT, Nykänen H, Turunen J, Martikainen PJ (2003) Methane emissions from natural peatlands in the northern boreal zone in Finland, Fennoscandia. Atmospheric Environment 37:147–151

Joosten H, Couwenberg J (2001) Bilanzen zum Moorverlust– das Beispiel Europa. In: Succow M, Joosten H (eds) Landschaftsökologische Moorkunde. Schweizerbart’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart, pp 406–409

Jǿrgensen CJ, Elberling B (2012) Effects of flooding-induced N2O production, consumption and emission dynamics on the annual N2O emission budget in wetland soil. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 53:9–17

Juszczak R (2013) Biases in methane chamber measurements in peatlands. International Agrophysics 27:159–168

Juszczak R, Acosta M, Olejnik J (2012) Comparison of daytime and nighttime ecosystem respiration measured by the closed chamber technique on temperate mire in Poland. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies 21(3):643–658

Juszczak R, Humphreys E, Acosta M, Michalak M, Kayzer D, Olejnik J (2013) Ecosystem respiration in a heterogeneous temperate peatland and its sensitivity to peat temperature and water table depth. Plant and Soil 366(1–2):505–520

Kolb S, Horn MA (2012) Microbial CH4 and N2O consumption in acidic wetlands. Frontiers in Microbiology 3:78. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00078

Kowalska N, Chojnicki BH, Rinne J, Haapanala S, Siedlecki P, Urbaniak M, Juszczak R, Olejnik J (2013). Measurements of methane emission from a temperate wetland by the eddy covariance method. International Agrophysics 27:283–289

Lai DYF (2009) Methane dynamics in Northern peatlands: a review. Pedosphere 19(4):409–421

Le Mer J, Roger P (2001) Production, oxidation, emission and consumption of methane by soils: a review. European Journal of Soil Biology 37:25–50

Livingston GP, Hutchinson GL (1995) Enclosure-based measurement of trace gas exchange: application and sources of error. In: Matson PA, Harriss RC (eds) Biogenic trace gases: measuring emissions from soil and water. Blackwell Science, Cambridge, pp 14–50

Lloyd J, Taylor JA (1994) On the temperature dependence of soil respiration. Functional Ecology 8:315–323

Loftfield N, Flessa H, Augustin J, Beese F (1997) Automated gas chromatograhic system for rapid analysis of the atmospheric trace gases CH4, CO2 and N2O. Journal of Environmental Quality 26:560–564

Lohila A, Aurela M, Hatakka J, Pihlatie M, Minkkinen K, Penttila T, Laurila T (2010) Resposnes of N2O fluxes to temperature, water table and N deposition in a northern boreal fen. European Journal of Soil Science 61(5):651–661

Martikainen PJ, Nykänen H, Crill P, Silvola J (1993) Effect of water on nitrous oxide fluxes from northern peatland. Nature 366:51–53

Michalak-Galczewska M (2011) Daily and seasonal variability of CO2 fluxes on the Rzecin peatland (in Polish). PhD dissertation, Meteorology Department of Poznan University of Life Sciences

Moore TR (1994) Trace gas emissions from Canadian peatlands and the effect of climatic change. Wetlands 14:223–228

Moore T, Roulet NT, Knowles R (1990) Spatial and temporal variations of methane flux from subarctic/northern boreal fens. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 4:29–46

Moore TR, DeYoung A, Bubier JL, Humphreys E, Lafleur PM, Roulet N (2011) A multi-year record of methane flux at the Mer Blue bog, southern Canada. Ecosystems 14:646–657

Nykänen H, Alm J, Silvola J, Tolonen K, Martikainen PJ (1998) Methane fluxes on boreal peatlands of different fertility and the effect of long-term experimental lowering of the water table on flux rates. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 12:53–69

Pihlatie M, Christiansen JR, Aaltonen H, Korhonen J, Nordbo A, Rasilo T, Benanti G, Giebels M, Helmy M, Hirvensalo J, Jones S, Juszczak R, Klefoth R, Lobo do Vale R, Rosa AP, Schreiber P, Serça D, Vicca S, Wolf B, Pumpanen J (2013) Comparison of static chambers to measure CH4 emissions from soils. Agriculture and Forest Meteorology 171–172:124–136

Rees RM, Agustin J, Alberti G, Ball BC, Boeckx P, Canterel A, Castaldi S, Chirinda N, Chojnicki B, Giebels M, Gordon H, Horvath L, Juszczak R, Kasimir Klemedtsson Å, Klemedtsson L, Medinets S, Machon A, Mapanda F, Olesen J, Reay D, Sanchez L, Smith KA, Sowerby A, Sommer M, Soussana JF, Stenberg M, Topp CFE, van Cleemput O, Vallejo A, Watson CA, Wuta M (2013) Nitrous oxide emissions from European agriculture; an analysis of variability and drivers of emissions from field experiments. Biogeosciences 10:2671–2682

Regina K, Nykänen H, Silvola J, Martikainen PJ (1996) Fluxes of nitrous oxide from boreal peatlands as affected by peatland type, water table level and nitrification capacity. Biogeochemistry 35:401–418

Rinne J, Riutta T, Pihlatie M, Aurela M, Haapanala S, Tuovinen J-P, Tuittila E-S, Vesala T (2007) Annual cycle of methane emission from a boreal fen measured by the eddy covariance technique. Tellus B 59(3):449–457

Rückauf U, Augustin J, Russow R, Merbach W (2004) Nitrate removal from drained and reflooded fen soil affected by soil N transformation processes and plant uptake. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 36:77–90

Rydin H, Jeglum J (2006) The biology of peatlands. Oxford University Press, New York, 343 pp

Saarinen T (1996) Biomass and production of two vascular plants in a boreal mesotrophic fen. Canadian Journal of Botany 74:934–938

Saarnio S, Winiwarter W, Leitao J (2009) Methane release from wetlands and watercourses in Europe. Atmospheric Environment 43:1421–1429

Sachs T, Giebels M, Boike J, Kutzbach L (2010) Environmental controls on CH4 emission from polygonal tundra on microsite scale in the Lena river delta, Siberia. Global Change Biology 16:3096–3110

Schiller CL, Hastie DR (1994) Exchange of nitrous oxide within the Hudson Bay lowland. Journal of Geophysical Research 99(D1):1573–1588. doi:10.1029/93JD01358

Shannon RD, White JR (1994) A three-year study of controls on methane emissions from two Michigan peatlands. Biogeochemistry 27:35–60

Sundh I, Mikkel C, Nilsson M, Svensson BH (1995) Potential aerobic methane oxidation in a Sphagnum-dominated peatland - Controlling factors and relation to methane emission. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 27(6):829–837

Suyker AE, Verma SB, Clement RJ, Billesbach DP (1996) Methane flux in a boreal fen: season-long measurement by eddy correlation. Journal of Geophysical Research 101:28637–28647

Treat CC, Bubier JL, Varner RK, Crill PM (2007) Time scale dependence of environmental and plantmediated controls on CH4 flux in a temperate fen. Journal of Geophysical Research 112, G01014. doi:10.1029/2006JG000210

Vasander H, Tuittila E-S, Lode E, Lundin L, Ilomets M, Sallantaus T, Heikkilä R, Pitkänen M-L, Laine J (2003) Status and restoration of peatlands in northern Europe. Wetlands Ecology and Management 11:51–63

Well R, Augustin J, Meyer K, Myrold DD (2003) Comparison of field and laboratory measurement of denitrification and N2O production in the saturated zone of hydromorphic soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 35:783–799

Whalen SC (2005) Biogeochemistry of methane exchange between natural wetlands and the atmosphere. Environmental Engineering Science 22(1):73–94

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Tomek Serba from PULS, Poland, who took samples of gases from the SIGMA chambers for GC analyses in ZALF, Müncheberg, Germany and Bodo Grossmann who did the gas chromatographic analyses in ZALF. We would like to express our gratitude to Dr. E.R. Humphreys from Carleton University in Canada who provided comments on the manuscript. Funding was provided by the EU FP6 Project NITROEUROPE-IP, GOCE-CT-2006-017841 “The nitrogen cycle and its influence on the European greenhouse gas balance” and EU FP7 Project GHG-Europe FP7-CP-IP-244122-2010 “Greenhouse gas management in European land use systems” and FP 7 Project INGOS, No. 284274 “Integrated non-CO 2 Greenhouse Gas Observation System” and project of Polish Ministry of Science (No. 752/N-COST/2010/0) “Assessment of a seasonal and spatial variation of plant biophysical and spectral indices (NDVI, WBI, LAI) in the context of CO 2 , CH 4 , H 2 O gas exchange between wetland, forest and arable ecosystems and the atmosphere”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Juszczak, R., Augustin, J. Exchange of the Greenhouse Gases Methane and Nitrous Oxide Between the Atmosphere and a Temperate Peatland in Central Europe. Wetlands 33, 895–907 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-013-0448-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-013-0448-3