Abstract

Purpose

Females remain under-represented in academic anesthesiology. Our objectives were to investigate gender differences over time in the first and last authors of published articles as well as corresponding citation rates in the Canadian Journal of Anesthesia (CJA).

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional, retrospective analysis of first and last authors’ gender from editorials and original articles published in the CJA in a sample of one calendar year of each decade between 1954 to 2017. We analyzed the relationships between author gender, year of publication, article type, and number of citations.

Results

Out of 639 articles identified, 542 (85%) were original investigations and 97 (15%) were editorials. Where gender could be confidently identified, the majority (461/571, 81%) of first authors were male. Although there was an increase in the proportion of female first authors over time, this increase was outpaced by the overall increase in female anesthesiologists in Canada. Original articles received more citations and were more likely to have a female first author than editorial articles were. An original article with a female first author resulted in 0.34 (95% confidence interval, 0.28 to 0.39; P < 0.001) more citations per article than a male first author when adjusting for year of publication.

Conclusions

Our study shows that, despite a slow increase over time, female authors are under-represented relative to male authors in the CJA and relative to the changing demographics of anesthesiologists in Canada. The reasons for this disparity are multifactorial and further research is needed to identify effective solutions.

Résumé

Objectif

Les femmes restent sous-représentées dans le monde de l’anesthésiologie universitaire. Nos objectifs étaient d’étudier l’évolution des premiers et derniers auteurs en fonction du sexe au fil des années dans les articles publiés ainsi que les taux correspondants de citation dans le Journal canadien d’anesthésie (CJA).

Méthodes

Nous avons mené une analyse transversale rétrospective du sexe des premiers et derniers auteurs des éditoriaux et des articles originaux publiés dans le CJA dans un échantillon d’une année civile pour chaque décennie entre 1954 et 2017. Nous avons analysé les rapports entre le sexe des auteurs, l’année de publication, le type d’articles et le nombre de citations.

Résultats

Sur 639 articles identifiés, 542 (85 %) étaient des recherches originales et 97 (15 %) étaient des éditoriaux. Lorsque le sexe a pu être identifié avec certitude, la majorité des premiers auteurs (461/571, 81 %) étaient des hommes. Bien qu’il y ait eu une augmentation du pourcentage de femmes premières auteures au fil du temps, cette augmentation n’a pas suivi la progression du nombre global des femmes anesthésiologistes au Canada. Les articles originaux ont été cités plus souvent et ont été plus susceptibles d’avoir un premier auteur féminin que les éditoriaux. Après ajustement pour l’année de publication, un article original dont le premier auteur était une femme comptait 0,34 (intervalle de confiance à 95 %, 0,28 à 0,39; P < 0,001) fois plus de citations que lorsque le premier auteur était un homme.

Conclusions

Notre étude montre que, malgré une lente augmentation avec les années, les femmes auteures sont sous-représentées par rapport à leurs collègues masculins dans le CJA et par rapport aux changements démographiques de l’anesthésiologie au Canada. Les raisons de cette disparité sont multifactorielles et d’autres recherches sont nécessaires pour trouver des solutions efficaces.

Similar content being viewed by others

Women now make up the majority of healthcare professionals working in many specialties in North America, including family medicine, pediatrics, and obstetrics and gynecology, and the number of women continues to increase in other specialties.1 In 2016, 54% of anesthesiologists under the age of 34 yr in Canada were women, although only 22% were women aged 65 yr and older.2 Despite this increase in the proportion of female anesthesiologists over time, women remain under-represented in academic medicine and leadership positions.3,4 Possible explanations for this disparity include family responsibilities,5 inadequate mentorship,6 lack of interest in academic medicine,7 or the “pipeline effect,” where there has not been enough time to see an improvement and attrition of women to other specialties.8 Recently, research has suggested that organizational factors contribute to reduced diversity, including implicit bias and lack of diversity at leadership levels.9

Previous studies have highlighted potential gender differences in authorship at major academic journals in anesthesiology (including the British Journal of Anaesthesia,10Anesthesiology, and Anesthesia and Analgesia)11 and other specialties.1 Currently, the proportion of female authors published in the Canadian Journal of Anesthesia (CJA) and the trends in author gender over time are unknown.

Inspired by Galley et al.,10 our study objectives were to: 1) determine the proportion of female first and last authors of original and editorial articles; 2) compare changes in the proportion of female first and last authors over time with the proportion of practicing female anesthesiologists in Canada since the CJA was established; 3) compare differences in author gender between editorial and original article types; and 4) determine differences in citation rates between those articles published in the CJA by females and males.

Methods

Design

We conducted a cross-sectional, retrospective analysis of all the primary (i.e., first position in the authorship line) and the senior (i.e., last position in the authorship line) authors’ gender from articles published in the CJA in the first year (January 1 to December 31, inclusively) of each of the first seven decades since the CJA’s inception as well as in the most recent complete calendar year (i.e., 1954, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2017). The article types that we included were all reports of original investigation that are typically unsolicited submissions as well as editorials that are typically invited manuscripts by the journal’s editorial board. We excluded all review articles/brief reviews, images in anesthesia, correspondence, replies to correspondence, books, case reports, continuing professional development, special articles, and errata. Research Ethics Board approval was not required for this study as we included only publicly available data from the Internet. We chose to include both original articles and editorial articles specifically to ensure that we examined articles that were both unsolicited and solicited, respectively. We focused on first and last authorship as these positions typically carry the most weight in academic promotions,12 although first authorship was considered the most objectively important position.

Data collection and outcome measures

Our study focused on the role of gender rather than sex amongst authors in the CJA. Sex is the biological difference between male and female, whereas gender encompasses the socially-constructed norms, rooted in culture, that differentiate sex (i.e., woman and man);13 in other words and an extreme oversimplification and binarist view, gender refers to what is characteristically masculine or feminine.13 Herein, we use gender as an all-encompassing term but remain cognizant that we are not including unexamined categories of gender to incorporate differently gendered sexual continuities.14

We identified articles meeting our inclusion criteria in the CJA (www.springer.com/medicine/anesthesiology/journal/12630) and extracted the following data for each article: publication year, first author, last author, article type (original vs editorial) and country of origin. We then assigned a gender to each of the identified authors by one or more of the following methods: 1) general review of the author’s first and middle names; 2) Internet search of the author’s name and review for photographs or use of gender-specific terminology in relation to the author (e.g., “he” or “she”); 3) online search of the author’s first name for typical gender assignment (https://www.genderchecker.com/); and/or 4) contacting the corresponding author to establish the gender of a co-author. When a sole author was associated with a particular publication, the author’s gender was coded as the first author. The number of citations for each article was obtained from the CJA’s website. Missing data (i.e., the inability to assign gender with confidence) were omitted from the analysis. We determined the country of origin for first authors using the author affiliation listed on the manuscript. If authors had multiple affiliations, the first listed affiliation was recorded.

The proportion of practicing female anesthesiologists in Canada at specific time points was obtained from the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) website (https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/profiles/anesthesiology-e.pdf), which presents data relevant to anesthesiology collected from national physician surveys in Canada (https://www.cma.ca/En/Pages/cma-physician-data-centre.aspx). These surveys were distributed by email and social media to both CMA members and non-members, including those in full-time or part-time practice, locum tenens, semi-retired, or employed in any medically related field. Of those emailed, data collection lasted for two months, with four reminders circulated. Medical students, residents and retired physicians were not eligible to participate.

Analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistical analyses (e.g., percentage, median, interquartile range [IQR]). Poisson regression was used to analyze differences in citation rates between author gender with year of publication included as a covariate. A P < 0.05 was considered significant and all data was analyzed using STATA 12.1 (StataCorp, TX, USA).

Results

Our initial screen identified 639 articles, including 542 original research articles and 97 editorials. We were unable to identify the gender of 68 (11%) first authors and 56 (9%) last authors, with missing gender being more common in editorial articles and earlier years of the dataset (19% in 1980 and earlier vs 6% after 1980). In addition, 130 (20%) articles (60 editorials and 70 original articles) had a single author. The number of citations was available for all but four (0.6%) articles. The total number of articles analyzed per year peaked in 1990 with a slight decline in the most recent years. The total number of editorials published per year increased over time while the number of original articles declined after 1990.

Fifty-eight percent (372/639) of first authors were from Canada, 22% (139/639) from the United States, 5% (32/639) from Japan, 2% (13/639) from France, and 1% (7/639) from Germany. Ten percent were from a variety of other countries (each contributing less than 1% or five articles). Country of origin was not provided in 2% (12/639) of articles. Where country of origin was available, 81% (77/95) of editorials had a Canadian first author compared with 55% (295/532) of original articles.

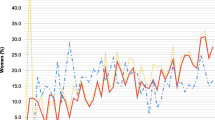

Proportion of female first and last authors

The majority of articles were published by male first authors (461/571, 81%) and male last authors (369/453, 81%) (Table 1), although there was an increase in the proportion of female authors over time (Figure, electronic supplementary material [ESM] eTables 1 and 2). Overall, first authors were female in 20% (94/476) of original articles and 17% (16/95) of editorial articles. The most recent year of the dataset (2017) revealed 24% (22/92) of first authors and 22% (16/74) of last authors were female, although the proportion of female anesthesiologists in Canada in 2017 was 32%. The proportion of female anesthesiologists in Canada appears to continue to outpace the proportion of female authors (Figure). The gender composition of first and last author combinations in articles with more than one author (n = 419) remained stable over time, with 66% (277/419) of publications having both a male first and last author, 28% (116/419) having a mixed pairing, and 6% (26/419) having both a female first and last author. A detailed breakdown of first and last author gender, stratified by year and article type, as well as the gender of anesthesiologists practicing in Canada when available, is provided in the ESM (eTables 1 and 2).

Proportion of female first authors over time, stratified by article type. The dashed line represents the proportion of female anesthesiologists in Canada; these data were available from 2000 onwards (source: Canadian Medical Association https://www.cma.ca/En/Pages/physician-historical-data.aspx)

When considering only articles published by Canadian first authors, 22% (75/338) of first authors were female, although this number rose to 32% (20/62) when looking at the most recent year of the dataset (2017). In a subset of articles with Canadian first authors, Canadian women remained under-represented in editorial articles compared with original articles (17% [13/76] vs 24% [62/262]). In the most recent year of the dataset (2017), the proportion of Canadian first authors of original articles that were female increased to 42% (16/38), in contrast with the proportion of Canadian first authors of editorials that were female (17% [4/24]).

Differences in author gender between editorials and original articles over time

There were 168 articles (30%) that included at least one female first or last author, with original articles having females in at least one of these author positions 32% (145/313) of the time compared with 24% (23/94) of editorials (P = 0.17). Over the entire dataset, females authored original articles and editorials at similar rates in the first author position (94/476 [20%] vs 16/95 [17%], respectively, P = 0.51), although this gap widened in the most recent year of the dataset (16/60 [27%] vs 6/32 [19%], respectively) (ESM, eTable 1).

Relationship between author gender and citation rates

On average, articles were cited a median [IQR] of 5 [1-14] times with original articles receiving more citations than editorial articles (8 [2-16] vs 2 [0-4] citations per article, respectively; P < 0.001). Original articles with a female first author received more citations (Table 2). Similarly, mixed gender first and last author pairings (e.g., male-female or female-male) received more citations than same gender pairings (e.g., male-male or female-female) (Table 2). This relationship appeared to be predominantly in original research articles where, on average, an original article with a female first author resulted in 0.34 more citations per article (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.28 to 0.39; P < 0.001) compared with an article without a female first author, after adjustment for year of publication. In contrast, citation rates of editorials were similar regardless of first author gender (-0.19 citations per article with a female first author; 95% CI, -0.51 to 0.14; P = 0.26).

Discussion

Our study shows that, despite an increase in the proportion of females practicing anesthesiology in Canada, females are under-represented in first and last authorship of published articles in the CJA. Although our study demonstrated an overall steady increase in authorship by females of original articles in the CJA, this increase continues to be outpaced by the increase in female anesthesiologists in Canada and occurred even in the most recent years of the dataset (2017) where females represented 24% (22/92) of first authors of original articles compared with 32% (1060/3318) of Canadian anesthesiologists. In particular, first authorship by females of solicited editorial articles (6/32 [19%] in 2017) has continued to lag behind first authorship by females of original articles (16/60 [27%] in 2017). Moreover, when we examined the subset of Canadian first authors, the proportion of female first authors of solicited editorial articles (13/76 [17%]) remained severely under-represented compared with original articles (16/38 [42%]) in the most recent year of the dataset. Interestingly, our analysis found that articles with a female first author resulted in a higher citation rate for original articles, yet female authors remain under-represented as first authors of solicited editorial articles. The criteria for advancement in academic anesthesiology typically prioritizes academic productivity including original research publications and invited editorials. Therefore, our findings have important implications for the academic advancement of women in anesthesiology.3

These findings are not unique to the CJA, but reflect a broader problem in academic medicine. The lower representation of female first authors in the CJA is consistent with similar studies in other medical subspecialties such as pediatrics11 and gastroenterology,15 and these trends remain pervasive in academic medical publishing.3,10,12 Similar to our findings, 61% of published articles in the British Journal of Anaesthesia were authored by a male first author and a male last author, 24% by a female first author and a male last author, 8% by a male first author and a female last author, and only 7% by a female first author and a female last author.10 In a recent study in Anesthesia and Analgesia, a higher proportion of females were first authors of publications in Anesthesiology (32%) and Anesthesia and Analgesia (30%)11; nevertheless, this analysis included more recent articles from 2002 onwards.11 Interestingly, the proportion of female first authors in the CJA peaked in 2000, with a subsequent decline to present. The reasons for this observation are unclear and could reflect changes in institutional or systemic barriers, the population of researchers submitting to the CJA, or random chance.

The reasons behind our study’s findings are likely multifactorial and may reflect a lower level of female participation in anesthesiology research (including manuscript submissions), systemic barriers to manuscript acceptance (such as implicit bias in peer review and invited authorship), or a combination of factors. Although peer reviewers’ gender at the CJA could theoretically also have influenced acceptance rates amongst female authors, we do not have access to this information. Although the relationship between reviewer and author gender on acceptance rates is conflicting,15,16 a recent study found gender bias in all-male reviewer teams favoring male last authors.17 A lower original and editorial article submission rate from female authors may result from demographic differences between male and female anesthesiologists in Canada as well as other countries, as a larger proportion of female anesthesiologists in Canada are earlier in their academic careers. This may have contributed to the disparity in editorial authorship in particular, which typically requires a higher degree of seniority. Nevertheless, the low percentage of editorials by females cannot be fully explained by this factor as the proportion of female authors does not parallel the proportion of female anesthesiologists across the age spectrum. Previous research refutes the insufficient pipeline18 and has suggested institutional bias contributes to this gender disparity. Another explanation is that females may publish articles other than those included in the study more frequently, such as review articles and correspondence. We found that the total number of articles analyzed declined after 1990, likely due to increased publication of other article types not included in our analysis rather than an actual decline in total articles, and the representation of females amongst these authors is unknown.

Mounting evidence across different specialties and countries have suggested several potential systemic barriers to academic advancement of female physicians, which may contribute to our findings. For example, women are less likely than men to receive awards and distinctions,9 be promoted to higher academic ranks despite similar achievements,19 and are more likely to experience sexual harassment in their academic environment,20 all of which lead to selective attrition. Women may also be hindered by implicit bias and subtle forms of discrimination as they progress in their academic career (e.g., being called by their first names more frequently than men when presenting at academic grand rounds).21 In anesthesiology, women remain severely under-represented amongst award recipients at the Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society (CAS), including those targeted at early career anesthesiologists.2 Notably, few women were nominated for awards at the CAS rather than not being selected.22 In our study, the lower levels of female first authors of solicited editorials relative to original articles is concerning, particularly amongst Canadian authors, and deserves further investigation. Future research should focus on barriers to participation in academic anesthesiology, similar to research done on female surgeons.23

Interestingly, articles with a female first author had a higher citation rate than those with a male first author. The reasons for this are unclear, although we can speculate that gender diversity may have positively influenced the quality of the research. In domains outside of medicine, gender diversity in business management is associated with improved performance in companies focused on innovation,24 and gender diverse teams are more innovative than single gender teams.25 Other possible explanations for this finding include an unmeasured confounder, for example country of origin or research topic.

Several solutions have been proposed to address the gender disparity in anesthesia research and publication. Mentorship is often proposed as a solution and is a valued factor in career advancement in academic medicine in general26,27 as well as in anesthesiology specifically.28 As female anesthesiologists prefer female mentors,29,30 and female mentors advance the careers of female colleagues,31,32 cultivating senior female academic mentors is essential. Other potential solutions to reduce the risk of implicit bias in academic medical publishing include identifying gender composition of peer reviewers and correcting female under-representation, if present. In addition, training of reviewers on implicit bias may be useful (e.g., implicit association test)33 as a previous study found that papers authored by women spend six months longer in peer review.34 Although double-blinded reviews were thought to result in more female-authored publications,35 Webb et al. challenged these conclusions.36 Finally, increasing the diversity of journal editorial boards may also help mitigate gender disparities, particularly for invited publications such as editorials. The most important first step towards addressing gender disparities in academic medicine is to measure data on participation by women and to follow this over time to ensure interventions are effective.9

Limitations

We selected eight years of the dataset, which may not have been representative of all years; however, we speculate that the general trends would not have been different. In addition, we were unable to identify the gender of several authors (particularly those from older years where initials were commonly used), which may have introduced selection bias. Given that male authors were more prevalent in earlier issues, this missing data may have led us to overestimate authorship by females. Also, we are unable to determine the proportion of manuscripts submitted versus those manuscripts accepted by female authors: without having the denominator of manuscripts submitted, we cannot ascertain the presence or absence of gender bias in peer review and other editorial processes.

We were also limited by the nature of the data, including a lack of distinction between non-anesthesiologist and anesthesiologist authors. Female authors may also be more likely to submit manuscripts to journals in other streams such as educational journals. These variables limit our ability to fully determine the participation of female anesthesiologists in research in Canada. Finally, authorship ranking is a non-validated metric and not used by the International Committee of Medical Journal Authors. We used the first-last-author-emphasis model as described by Tscharntke,37 a model that has been used in several previous analyses of author gender in journal publications.1,10,11 We did not cross reference first and last authors with corresponding authors or with author contributions, which may have provided a more accurate representation of credit for author contribution than assuming that first and last author positions are the most important for academic promotion. Finally, we used data from the CMA physician surveys to determine the proportion of female anesthesiologists in Canada, which may not be an accurate representation because of the sampling techniques.

Conclusion

Overall, our study demonstrates that, despite an increase in the proportion of female authors over time, female first and last authors remain under-represented relative to male authors in the CJA. Our analysis does not distinguish between reduced submission rates from female authors or higher rejection rates. The reasons for this disparity are likely multifactorial. Original articles authored by a female first author were associated with a higher rate of citations compared with those by male first authors, suggesting that increasing female authorship may result in higher impact research. Solicited editorials were less likely to have females as first or last authors over time compared with original research articles, and this effect was magnified amongst the subset of Canadian first authors. Further research into understanding barriers to academic success and advancement in academic anesthesiology for female physicians is urgently needed to identify effective interventions.

References

Jagsi R, Guancial EA, Worobey CC, et al. The “gender gap” in authorship of academic medical literature: a 35-year perspective. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 281-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa053910.

Mottiar M. Because it’s 2018: women in Canadian anesthesiology. Can J Anesth 2018; 65: 953-4.

Leslie K, Hopf HW, Houston P, O’Sullivan E. Women, minorities, and leadership in anesthesiology: take the pledge. Anesth Analg 2017; 124: 1394-6.

Toledo P, Duce L, Adams J, Ross VH, Thompson KM, Wong CA. Diversity in the American Society of Anesthesiologists leadership. Anesth Analg 2017; 124: 1611-6.

Straehley CJ, Longo P. Family issues affecting women in medicine, particularly women surgeons. Am J Surg 2006; 192: 695-8.

Colletti LM, Mulholland MW, Sonnad SS. Perceived obstacles to career success for women in academic surgery. Arch Surg 2000; 135: 972-7.

Wright AL, Schwindt LA, Bassford TL, et al. Gender differences in academic advancement: patterns, causes, and potential solutions in one US College of Medicine. Acad Med 2003; 78: 500-8.

Sexton KW, Hocking KM, Wise E, et al. Women in academic surgery: the pipeline is busted. J Surg Educ 2012; 69: 84-90.

Silver JK, Slocum CS, Bank AM, et al. Where are the women? The underrepresentation of women physicians among recognition award recipients from medical specialty societies. PM&R 2017; 9: 804-15.

Galley HF, Colvin LA III. Next on the agenda: gender. Br J Anaesth 2013; 111: 139-42.

Miller J, Chuba E, Deiner S, DeMaria S Jr, Katz D. Trends in authorship in anesthesiology journals. Anesth Analg 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000003949.

Silver JK, Poorman JA, Reilly JM, Spector ND, Goldstein R, Zafonte RD. Assessment of women physicians among authors of perspective-type articles published in high-impact pediatric journals. JAMA Netw Open 2018; 1: e180802.

Long MT, Leszczynski A, Thompson KD, Wasan SK, Calderwood AH. Female authorship in major academic gastroenterology journals: a look over 20 years. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 81(1440-7): e3.

Butler J. Gender Trouble. Routledge; 2011.

Tamblyn R, Girard N, Qian CJ, Hanley J. Assessment of potential bias in research grant peer review in Canada. CMAJ 2018; 190: E489-99.

Gilbert JR, Williams ES, Lundberg GD. Is there gender bias in JAMA’s peer review process? JAMA 1994; 272: 139-42.

Murray D, Siler K, Lariviére V, et al. Gender and international diversity improves equity in peer review. bioRxiv 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/400515.

Carnes M, Morrissey C, Geller SE. Women“s health and women”s leadership in academic medicine: hitting the same glass ceiling? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008; 17: 1453-62.

Reed V, Buddeberg-Fischer B. Career obstacles for women in medicine: an overview. Med Educ 2001; 35: 139-47.

Lindquist C, McKay T. Sexual harassment experiences and consequences for women faculty in science, engineering, and medicine. Publication No. PB-0018-1806. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI Press. Available from URL: https://doi.org/10.3768/rtipress.2018.pb.0018.1806. Accessed Dec 2018.

Files JA, Mayer AP, Ko MG, et al. Speaker introductions at internal medicine grand rounds: forms of address reveal gender bias. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2017; 26: 413-9.

DuVal D, McKnight D. In reply to “Because it’s 2018: women in Canadian anesthesiology”. Can J Anesth 2018; 65: 955.

Seemann NM, Webster F, Holden HA, et al. Women in academic surgery: why is the playing field still not level? Am J Surg 2016; 211: 343-9.

Dezsö CL, Gaddis Ross D. Does female representation in top management improve firm performance? A panel data investigation. Strateg Manag J 2012; 33: 1072-89.

Marsch J. Women in science-what’s the world missing. Eur Sci Edit 2012; 38: 2.

Hoover EL. Mentoring women in academic surgery: overcoming institutional barriers to success. J Natl Med Assoc 2006; 98: 1542-5.

Jagsi R, Griffith KA, DeCastro RA, Ubel P. Sex, role models, and specialty choices among graduates of US medical schools in 2006-2008. J Am Coll Surg 2014; 218: 345-52.

Flexman AM, Gelb AW. Mentorship in anesthesia: how little we know. Can J Anesth 2012; 59: 241-5.

Zakus P, Gelb AW, Flexman AM. A survey of mentorship among Canadian anesthesiology residents. Can J Anesth 2015; 62: 972-8.

Plyley T, Cory J, Lorello GR, Flexman AM. A survey of mentor gender preferences amongst anesthesiology residents at the University of British Columbia. Can J Anesth 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-018-1260-6.

Levine RB, Mechaber HF, Reddy ST, Cayea D, Harrison RA. “A good career choice for women”: female medical students’ mentoring experiences a multi-institutional qualitative study. Acad Med 2013; 88: 527-34.

Mayer KL, Perez RV, Ho HS. Factors affecting choice of surgical residency training program. J Surg Res 2001; 98: 71-5.

Sukhera J, Milne A, Teunissen PW, Lingard L, Watling C. Adaptive reinventing: implicit bias and the co-construction of social change. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2018; 23: 587-99.

Hengel E. Publishing while female. Are women held to higher standards? Evidence from peer review - 2017. Available from URL: https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/270621. Accessed Dec 2018.

Budden AE, Tregenza T, Aarssen LW, Koricheva J, Leimu R, Lortie CJ. Double-blind review favours increased representation of female authors. Trends Ecol Evol 2008; 23: 4-6.

Webb TJ, O’Hara B, Freckleton RP. Does double-blind review benefit female authors? Trends Ecol Evol 2008; 23: 351-3.

Tscharntke T, Hochberg ME, Rand TA, Resh VH, Krauss J. Author sequence and credit for contributions in multiauthored publications. PLoS Biol 2007; 5: e18.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Hilary P. Grocott, Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia.

Author contributions

Alana M. Flexman was involved in the study concept and design, primary data verification, responsible for the accuracy of the statistical analyses, and critical revision of the manuscript’s intellectual content. Arun Parmar was involved in primary data collection and verification and data analysis and interpretation. Gianni R. Lorello was involved in the study concept and design, primary data collection, analysis and data interpretation, manuscript drafting, and critical revision of the manuscript’s intellectual content.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is accompanied by an editorial. Please see Can J Anesth 2019; 66: this issue.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Flexman, A.M., Parmar, A. & Lorello, G.R. Representation of female authors in the Canadian Journal of Anesthesia: a retrospective analysis of articles between 1954 and 2017. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 66, 495–502 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-019-01328-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-019-01328-5