Abstract

Background

Educators in anesthesia have an obligation to ensure that fellowship programs are training anesthesiologists to meet the highest standards of performance in clinical and academic practice. The objective of this survey was to characterize the perspectives of graduates of Canadian core fellowship programs in pediatric anesthesia (during a ten-year period starting in 2003) on the adequacies and inadequacies of fellowship training.

Methods

We conducted an electronic survey of graduates from eight departments of pediatric anesthesia in Canada who completed one-year core fellowship training in pediatric anesthesia from 2003 to 2013. A novel survey design was implemented, and the content and structure of the design were tested before distribution. Data were collected on respondents’ demographics, details of training and practice settings, perceived self-efficacy in subspecialty practices, research experience, and perspectives on one-year core fellowship training in pediatric anesthesia. Descriptive statistics and 95% confidence intervals were determined.

Results

The survey was sent to 132 anesthesiologists who completed core fellowship training in pediatric anesthesia in Canada. Sixty-five (49%) completed and eligible surveys were received. Most of the anesthesiologists surveyed perceived that 12 months of core fellowship training are sufficient to acquire the knowledge and critical skills needed to practice pediatric anesthesia. Subspecialty areas most frequently perceived to require improved training included pediatric cardiac anesthesia, chronic pain medicine, and regional anesthesia.

Conclusions

This survey reports perceived deficiencies in domains of pediatric anesthesia fellowship training. These findings should help guide the future development of core and advanced fellowship training programs in pediatric anesthesia.

Résumé

Contexte

Les éducateurs en anesthésie doivent garantir que les programmes de formation postdoctorale (les fellowships) enseignent aux anesthésiologistes à répondre aux normes les plus élevées en matière de performance dans la pratique clinique et académique. L’objectif de ce sondage était d’évaluer l’opinion des diplômés de programmes de fellowship canadiens en anesthésie pédiatrique ayant gradué entre 2003 et 2013 sur les forces et faiblesses de la formation postdoctorale.

Méthode

Nous avons mené un sondage en ligne auprès de diplômés provenant de huit départements d’anesthésie pédiatrique au Canada, ayant complété une formation postdoctorale d’un an en anesthésie pédiatrique entre 2003 et 2013. Un nouveau modèle de sondage fut créé, et le contenu et la structure de ce modèle furent testés avant la distribution du sondage. Diverses données furent colligées auprès des répondants, notamment des données démographiques, les détails de leur formation et de leur cadre de pratique, la perception de leur propre efficacité dans les pratiques surspécialisées, leur expérience de recherche et leurs opinions en général sur la formation postdoctorale d’un an en anesthésie pédiatrique. Des statistiques descriptives furent effectuées sur les résultats, avec intervalles de confiance à 95 %.

Résultats

Le sondage a été envoyé à 132 anesthésiologistes ayant complété une formation postdoctorale de base en anesthésie pédiatrique au Canada. Soixante-cinq (49%) questionnaires complétés et admissibles ont été reçus. Selon la plupart des anesthésiologistes sondés, douze mois de formation postdoctorale sont suffisants pour acquérir les connaissances et les compétences critiques nécessaires à pratiquer l’anesthésie pédiatrique. Les domaines de surspécialisation le plus fréquemment perçus comme nécessitant une formation plus approfondie étaient l’anesthésie cardiaque pédiatrique, la médecine de la douleur chronique et l’anesthésie régionale.

Conclusion

Ce sondage met en lumière les lacunes perçues dans divers domaines de la formation postdoctorale en anesthésie pédiatrique. Ces résultats seront utiles pour guider la mise au point future de programmes de formation postdoctorale de base et avancée en anesthésie pédiatrique.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Medical education is developing in tandem with education theory, patient safety standards, and quality in healthcare.1 Several factors are influencing the efforts of educators and program directors in anesthesia to re-evaluate postgraduate specialty training. Among these are the increasing complexity of clinical care and organizational systems in medicine2 and recognition that time-based training alone does not guarantee that clinical expertise will be either attained or sustained.3 In addition to training fellows to meet the highest standards of clinical care, programs must also establish a foundation for continued professional growth by developing specialists who can successfully function in leadership and advocacy roles in the future.4 To this end, some anesthesia programs have recommended changes to the structure of fellowship training to facilitate greater exposure to subspecialty practice5 and to foster greater participation in academic activity.6

In Canada, individual institutions determine the content and structure of fellowship programs in pediatric anesthesia. These 12-month clinical and academic programs aim to teach fellows the knowledge and critical skills needed to function as specialists in pediatric anesthesia. Currently, published data are lacking regarding the perceptions of graduates of core fellowship programs in pediatric anesthesia on whether the programs are meeting fellows’ needs and preparing them for independent practice. The objective of this survey was to characterize the perspectives of graduates of Canadian core fellowship programs in pediatric anesthesia (during a ten-year period starting in 2003) on the adequacies and inadequacies of fellowship training. It is anticipated that the results will help guide the efforts of program directors and educators to advance fellowship training in pediatric anesthesia.

Methods

This survey was approved (May, 2014) by the Research Ethics Board, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. A waiver of written informed consent was granted, and a standardized information sheet informing participants of the aims of the study accompanied the electronic survey. Return of the completed survey was considered to imply consent for participation in the study. We report the survey design, the sample size estimation, all measures used in the survey, and all data manipulations.7

Survey design

All university-affiliated departments of pediatric anesthesia in Canada (n = 11) were contacted by e-mail or telephone to identify departments that offered a core pediatric fellowship during the ten-year period (July 2003 to June 2013) of the survey. One department of pediatric anesthesia did not have any eligible fellows during the survey timeframe, and eight of the remaining ten departments (Alberta Children’s Hospital, British Columbia [BC] Children’s Hospital, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire [CHU] Sainte-Justine, Children’s Hospital Winnipeg, Izaak Walton Killam Children’s Hospital, Montreal Children’s Hospital, Stollery Children’s Hospital, and The Hospital for Sick Children) agreed to share data for the survey.

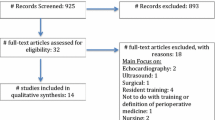

All anesthesiologists who completed 12 months of core fellowship training in pediatric anesthesia in Canada during the ten-year period were eligible to participate in the survey. Anesthesiologists who completed less than 12 months of core fellowship training and those who completed only advanced pediatric anesthesia (e.g., pediatric cardiac anesthesia) fellowship training in Canada were excluded from the survey. Representatives for each of the eight departments identified 164 graduates in total using local datasets. E-mail addresses were not available for 32 graduates. The remaining 132 graduates were included in the survey sample (80% of study population).

The 43-question survey instrument (Appendix) was a novel design conceived by the authors to characterize the perceptions of graduates of Canadian core fellowship programs in pediatric anesthesia on the adequacies and inadequacies of fellowship training and to explore the need for current trends in subspecialty program development in pediatric anesthesia.5 The survey comprised six sections evaluating (a) participants’ demographic information, (b) characteristics of clinical fellowship training undertaken, (c) details of current clinical, academic, and administrative practice settings, (d) scope of clinical practice in select pediatric anesthesia subspecialties, (e) participation in research, and (f) overall perspectives on core fellowship training in pediatric anesthesia and opportunities for improvement. Respondents were asked to assess their own performance in pediatric anesthesia subspecialty practices using four categories: not competent, competent (I can perform in this field of practice but may have to think about the steps and/or use a cognitive aid), proficient (I can skillfully perform in this field of practice and rarely have to think about the steps or use a cognitive aid), and expert (I can skillfully perform in this field of practice, and I am very comfortable teaching it and problem solving any challenges with it). These categories of performance were based on the novice-to-expert scale of the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition and the transition of clinical reasoning from analytic to non-analytic methods that occurs with learning.8 Respondents’ perceived self-efficacy after core fellowship training were assessed using a five-point Likert scale9 (1 = strongly agree; 2 = somewhat agree; 3 = neither agree nor disagree; 4 = somewhat disagree; and 5 = strongly disagree). Narrative comment sections were also included to collect respondents’ opinions on potential opportunities for improvement and feedback.

Sample size

Given a study population of 164 graduates, the minimum sample size required was estimated a priori to be 61 participants for a confidence level of 95% and a confidence interval (CI) of 10%. Based on the low response rates experienced by other surveys of healthcare professionals,10 we anticipated an overall completed survey response rate in the region of 40%, and accordingly, we invited all eligible and contactable graduates (n = 132) to participate.

Survey validity testing

The survey instrument was formally tested beforehand using a convenience sample of five pediatric anesthesia fellows at The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto who were asked to provide feedback on content, clarity, and comprehensiveness.7 No changes were required to the structure or content of the survey on the basis of this testing.

Survey administration

The self-administered electronic survey was offered to all eligible graduates from participating departments over a two-month period from May to June 2014. To maximize the response rate, two e-mail invitations were sent over a three-week period to all eligible participants. The reported data were anonymous for both graduates and training institutions. Non-response was categorized as no returned electronic survey, and a response to all questions was required for the survey to be returned.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools hosted at The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. REDCap is a secure web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies.11 Data were summarized as proportions of respondents. Descriptive statistics (central tendency and distribution) as appropriate for the data distribution and 95% CIs were determined.

Results

Demographics of survey respondents

Of the 132 graduates who were invited to participate, 67 completed the survey. Two respondents were excluded from analysis as they completed less than 12 months of core fellowship training, resulting in an overall response rate of 49%. The median (interquartile range [IQR]) age of fellows at the time of completing core fellowship training in pediatric anesthesia was 34 [32 - 36] yr, and 43% (28/65) of respondents were female.

Characteristics of past fellowship training and current practice settings

Characteristics of respondents’ postgraduate training (residency and fellowship) are described in Table 1. While only 18% of respondents completed residency training in Canada, almost half of respondents now practice in Canada, mainly in university-affiliated tertiary hospitals (Table 2). More than three-quarters of respondents reported that pediatric anesthesia accounted for the majority of their clinical practice (Table 2). Two-thirds have a university academic appointment (Table 2). Pediatric anesthesia subspecialties commonly practiced (> 20% of respondents) include regional anesthesia, neuroanesthesia, cranial vault or maxillo-facial anesthesia, acute pain medicine, cardiac anesthesia, and transplantation anesthesia.

Scope of subspecialty practice in pediatric anesthesia

While 69% (95% CI, 60 to 78) of respondents reported that they regularly provide pediatric cardiac anesthesia for children with congenital heart disease (CHD), a minority (23%; 95% CI, 16 to 30) provide anesthesia for pediatric cardiac surgery, and overall, only 18% (95% CI, 11 to 25) consider themselves to be “proficient” or “expert” in the provision of pediatric cardiac anesthesia (Table 3).

Most respondents (95%; 95% CI, 91 to 99) regularly perform pediatric regional anesthesia and perceive themselves to be “proficient” or “expert” in the practice of caudal analgesia (100%), epidural analgesia (89%; 95% CI, 84 to 94), trunk blocks (77%; 95% CI, 70 to 84), and lower limb blocks (68%; 95% CI, 60 to 76). Nevertheless, respondents had lower levels of perceived expertise for spinal analgesia (55%; 95% CI, 46 to 64), upper limb blocks (52%; 95% CI, 43 to 61), and ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia (UGRA). More than half of the respondents perceived themselves to be either “not competent” or only “competent” to perform ultrasound-guided peripheral or neuraxial regional anesthesia in children (Table 3).

All respondents considered themselves to be competent to manage acute pain in children, with 66% (95% CI, 57 to 75) regularly managing acute pain outside the operating room. Only 20% (95% CI, 5 to 21) treat chronic pain in children, and 5% of respondents devote ≥10% of their clinical practice to the management of children with chronic pain. The majority (62%; 95% CI, 53 to 71) consider themselves as being “not competent” to manage chronic pain in children (Table 3).

Perceived adequacy of core fellowship programs in pediatric anesthesia in Canada

Most respondents agreed or strongly agreed that completion of a 12-month core fellowship program in pediatric anesthesia is sufficient to provide safe anesthesia for neonates (74%; 95% CI, 66 to 82), infants (93%; 95% CI, 88 to 98), and children (96%; 95% CI, 92 to 100) (Table 4). The most frequently identified subspecialties requiring improved clinical exposure or education included pediatric cardiac anesthesia, regional anesthesia, and chronic pain medicine (Table 5).

Academic experience

Thirty-one percent of respondents (95% CI, 23 to 39) reported having one or more formal research qualifications (diploma [6%], master’s [15%], PhD [9%], or PhD equivalent [4%]). While over 80% (95% CI, 75 to 89) of respondents indicated that they participated in research during their fellowship, only 42% (95% CI, 33 to 51) presented this research at a national or international conference. Approximately half (95% CI, 42 to 60) of the respondents had published their research in a peer-reviewed journal. Since completing their fellowship training, 28% (95% CI, 20 to 36) had published no additional original research. Anesthesiologists who completed their training from 2003 to 2007 published a median [IQR] of 3 [1 - 5.75] papers; those who completed training from 2008 to 2010 published a median [IQR] of 2 [0 - 5] papers, and those who completed training from 2011 to 2013 published a median [IQR] of 1 [0 - 2] papers. Overall, 17% (95% CI, 10 to 24) of respondents published ≥ 6 scientific papers. Only 46% (95% CI, 37 to 56) reported that the necessary knowledge and skills to carry out or support research activities were acquired during their one-year core fellowship (Table 4).

Narrative feedback

In addition to the structured survey questions, the themes most frequently discussed by respondents included the need for improved research and clinical mentorship, more emphasis on developing future leaders in pediatric anesthesia, increased education in quality improvement, improved resource management rather than longer training, and the importance of continued education after fellowship training to maintain proficiencies and acquire new knowledge.

Discussion

We surveyed anesthesiologists who graduated from Canadian core fellowship training programs in pediatric anesthesia from 2003 to 2013. The survey revealed that the majority of the graduates consider that they provide safe anesthesia for neonates, infants, and children; however, it did identify certain self-perceived clinical deficiencies. Respondents reported a lack of perceived self-efficacy in certain clinical practice areas within pediatric anesthesia, including the anesthesia management of children with CHD, the use of UGRA, and the management of pediatric chronic pain.

Two-thirds of the anesthesiologists surveyed reported that they regularly provide anesthesia for children with CHD, yet 43% (95% CI, 34 to 52) consider themselves not competent to provide anesthesia to this population. This is concerning because the likelihood of survival among children with CHD is increasing and the need for noncardiac surgery among children with CHD is expected to increase in the future.12 Similarly, among anesthesiologists who regularly perform pediatric regional anesthesia, there was a self-perceived lack of competence in UGRA for both peripheral and neuraxial blocks. While empirical evidence evaluating UGRA and safety in children is still lacking, there are distinct theoretical advantages to using UGRA when placing regional blocks in unconscious children.13 In addition, there is an increasing expectation that anesthesiologists performing UGRA should be trained in the relevant core skills and proficiencies.14

The survey revealed that a proportion of anesthesiologists did undertake training in research at a level equivalent to a master’s or PhD. We did not conduct a multifaceted assessment of research activity as the “research age” of the majority of respondents was too low for accurate analysis of bibliometrics.15 Nevertheless, using the number of publications as a crude indicator of research productivity, it is evident that some anesthesiologists who complete fellowships are achieving a relatively high level of academic productivity in pediatric anesthesia.16 These anesthesiologists need to be identified early in their career to benefit from mentorship and intercalated subspecialty training during their core pediatric anesthesia fellowship. While integration of formal training in research or education methodology into advanced pediatric anesthesia fellowships can promote professional growth, postgraduate training at a master’s or PhD level is desirable to achieve sustained excellence in these areas.17

An overall aim of graduate medical education is the “development of the skills, knowledge, and attitudes required to enter the unsupervised practice of medicine”.18 In 2010, the Pediatric Anesthesia Fellowship Task Force was formed to review fellowship education standards in the United States of America and to make specific recommendations for improving fellowship training in pediatric anesthesia. This group recommended the development of an advanced second year of fellowship training in pediatric anesthesia to promote “academic leadership and advanced clinical subspecialty training”. Informed by a survey of chairs, chiefs, and program directors in pediatric anesthesia, the specific areas identified for advanced fellowship training were pediatric cardiac anesthesia, pediatric anesthesia education, pediatric anesthesia pain medicine, pediatric anesthesia quality and safety, and pediatric anesthesia research.5 These subspecialty areas identified by Andropoulos et al. are similar to the perceived inadequacies reported in this survey.5

While graduate medical education is frequently focused on achieving core competencies and specific performance objectives,19 some fellowship programs focus on duration of training and numbers of cases.20 Given constraints inherent in one-year fellowships, advanced second-year fellowships may be appropriate to improve graduate education in pediatric anesthesia.5 Nonetheless, there are doubts about whether the addition of time alone without significant structural change will improve clinical skills and enhance professional growth. Postgraduate specialist training in pediatric anesthesia must move beyond the clinical apprenticeship to encompass a more structured educational experience, as simply increasing the duration of training will not guarantee that expertise will be either attained or sustained.21 Enhancement of existing core pediatric anesthesia education is also necessary. Changes in the learning styles of students in graduate medical education22 and work-hour reforms in medicine have challenged educators and program directors to innovate and develop new methods to enhance traditional teaching.

This survey does not attempt to evaluate construct-specific competencies23; rather, it reports anesthesiologists’ perceived self-efficacy – the belief in one’s capabilities to use the available resources and execute the actions required to manage prospective situations24 – in specific subspecialties and domains of pediatric anesthesia. However, physicians’ ability to self-assess is known to be inaccurate, with little or no correlation demonstrated with external assessment. Furthermore, those who are the least skilled are often the least accurate in self-assessment.25 As a result, these data are valuable for exploring potential areas of improvement in training programs but cannot be used to indicate or quantify expertise in pediatric anesthesia.

This survey has other limitations. Survey item generation and reduction were conducted without the use of formal in-depth interviews or focus group sessions with experts.26 The investigators chose items for their relevance to current trends in subspecialty program development; however, by using this approach, other deficiencies in pediatric anesthesia fellowship training may have been missed. In addition, while the survey was pilot tested in individuals similar to those in the sampling frame, formal clinical sensibility testing was not undertaken.26 Despite including narrative sections to solicit comments on other areas for improvement and feedback, these deficiencies in the development and validation of the survey may introduce a risk of measurement bias.27 While the survey size is small, it represents a national population, and increasing the study period beyond ten years was not deemed appropriate considering the risk of recall bias as well as advances in the scope of clinical practice, education, and simulation that have occurred during this time. The relatively low response rate (49%) also introduces a risk of non-response bias. Similarly, the a priori CI was reasonably large (10%), but this was considered acceptable in the context of the anticipated response rate.

In conclusion, the majority of anesthesiologists surveyed agreed that 12 months of core fellowship training is sufficient to acquire the knowledge and critical skills needed to practice anesthesia for neonates, infants, and children. The subspecialty areas most frequently perceived to require improved training included pediatric cardiac anesthesia, regional anesthesia, and chronic pain medicine. It is anticipated that the results of this survey will help guide the efforts of educators and leaders in pediatric anesthesia to advance standards in pediatric anesthesia fellowship programs.

References

The Future of Medical Education in Canada Postgraduate Project. Available from URL: http://www.afmc.ca/future-of-medical-education-in-canada/postgraduate-project/ (accessed May 2015).

Sales CS, Schlaff AL. Reforming medical education: a review and synthesis of five critiques of medical practice. Soc Sci Med 2010; 70: 1665-8.

Naik VN, Wong AK, Hamstra SJ. Review article: Leading the future: guiding two predominant paradigm shifts in medical education through scholarship. Can J Anesth 2012; 59: 213-23.

Warren OJ, Carnall R. Medical leadership: why it’s important, what is required, and how we develop it. Postgrad Med J 2011; 87: 27-32.

Andropoulos DB, Walker SG, Kurth CD, Clark RM, Henry DB. Advanced second year fellowship training in pediatric anesthesiology in the United States. Anesth Analg 2014; 118: 800-8.

Schwinn DA, Balser JR. Anesthesiology physician scientists in academic medicine: a wake-up call. Anesthesiology 2006; 104: 170-8.

Story DA, Gin V, na Ranong V, Poustie S, Jones D, ANZCA Trials Group. Inconsistent survey reporting in anesthesia journals. Anesth Analg 2011; 113: 591-5.

Carraccio CL, Benson BJ, Nixon LJ, Derstine PL. From the educational bench to the clinical bedside: translating the Dreyfus developmental model to the learning of clinical skills. Acad Med 2008; 83: 761-7.

Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology 1932; 140: 1-55.

Cho YI, Johnson TP, Vangeest JB. Enhancing surveys of health care professionals: a meta-analysis of techniques to improve response. Eval Health Prof 2013; 36: 382-407.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42: 377-81.

Knowles RL, Bull C, Wren C, et al. Modelling survival and mortality risk to 15 years of age for a national cohort of children with serious congenital heart defects diagnosed in infancy. PLoS One 2014; 9: e106806.

Neal JM, Brull R, Chan VW, et al. The ASRA evidence-based medicine assessment of ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia and pain medicine: Executive summary. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2010; 35(2 Suppl): S1-9.

Sites BD, Chan VW, Neal JM, et al. The American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine and the European Society Of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy Joint Committee recommendations for education and training in ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009; 34: 40-6.

O’Leary JD, O’Sullivan O. Research productivity among trainee anaesthetists in Ireland: a cross-sectional study. Scientometrics 2012; 12: 431-8.

O’Leary JD, Crawford MW. Bibliographic characteristics of the research output of pediatric anesthesiologists in Canada. Can J Anesth 2010; 57: 573-7.

Merani S, Switzer N, Kayssi A, Blitz M, Ahmed N, Shapiro AM. Research productivity of residents and surgeons with formal research training. J Surg Educ 2014; 71: 865-70.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Pediatric Anesthesiology - 2014; Available from URL: https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/128/ProgramandInstitutionalAccreditation/Hospital-BasedSpecialties/Anesthesiology.aspx (accessed May 2015).

Frank JR. The CanMEDS 2005 Physician Competency Framework. Better Standards. Better Physicians. Better Care. Ottawa, ON - 2005. The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada and Associated Medical Services Inc. Available from URL: http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/common/documents/canmeds/resources/publications/framework_full_e.pdf (accessed Febraury 2015).

DiNardo JA, Andropoulos DB, Baum VC. Special article: A proposal for training in pediatric cardiac anesthesia. Anesth Analg 2010; 110: 1121-5.

McGowan FX Jr, Davis PJ. The advanced pediatric anesthesiology fellowship: moving beyond a clinical apprenticeship. Anesth Analg 2014; 118: 701-3.

Junco R, Mastrodicasa J. Connecting to the Net.Generation: What Higher Education Professionals Need to Know About Today’s Students. National Association of Student Personnel Administrators; 2007.

Whitehead CR, Kuper A, Hodges B, Ellaway R. Conceptual and practical challenges in the assessment of physician competencies. Med Teach 2015; 37: 245-51.

Eva KW, Regehr G. Self-assessment in the health professions: a reformulation and research agenda. Acad Med 2005; 80: S46-54.

Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van Harrison R, Thorpe KE, Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA 2006; 296: 1094-102.

Burns KE, Duffett M, Kho ME, et al. A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. CMAJ 2008; 179: 245-52.

Bryson GL, Turgeon AF, Choi PT. The science of opinion: survey methods in research. Can J Anesth 2012; 59: 736-42.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. M. Letal, Alberta Children’s Hospital; Dr. C. Montgomery, BC Children’s Hospital; Dr. K. Raghavendran, Children’s Hospital Winnipeg; Dr. J.L. Martinez, CHU Sainte-Justine; Dr. S. Bird, Izaak Walton Killam Children’s Hospital; Dr. D. Withington, Montreal Children’s Hospital; and Dr. L. Enwistle, Stollery Children’s Hospital for supporting this survey and providing contact information for fellows from their respective institutions.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Author contributions

James D. O’Leary and Mark W. Crawford helped design the study, analyze the data, and write the manuscript. They have seen the original study data and reviewed the analysis of the data. James D. O’Leary conducted the study and is the author responsible for archiving the study files.

Appendix

Appendix

Survey questionnaire

Item | Question | Response options, if applicable |

|---|---|---|

1. Demographics | ||

1(a) | Gender | Male / Female |

1(b) | What was your age (in years) when you completed your general pediatric anesthesia fellowship? | |

1(c) | Where did you complete your postgraduate/residency training prior to undertaking fellowship training in pediatric anesthesia? | Australia / Brazil / Canada / Germany / India / Ireland / Japan / New Zealand / Saudi Arabia / Sweden / United Kingdom / United States of America / Other (specify) |

2. Clinical fellowship training | ||

2(a) | Where did you complete your Canadian general pediatric fellowship training? | Alberta Children’s Hospital BC Children’s Hospital Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Children’s Hospital Winnipeg CHU Sainte-Justine Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto McMaster Children’s Hospital Montreal Children’s Hospital Stollery Children’s Hospital |

2(b) | When did you complete your general pediatric anesthesia fellowship, between: | 2004 to 2007 2008 to 2010 2011 to 2013 |

2(c) | What was the duration (in months) of general pediatric anesthesia fellowship? | |

2(d) | In addition to your general pediatric anesthesia fellowship, have you completed other PEDIATRIC specialty training? If yes, please describe the specialty, location, and duration of training. | Yes / No |

2(e) | In addition to your general pediatric anesthesia fellowship, have you completed other NON-PEDIATRIC specialty training? If yes, please describe the specialty, location, and duration of training. | Yes / No |

3. Clinical and administrative practice settings | ||

3(a) | In which country do you currently practice? | Australia / Brazil / Canada / Germany / India / Ireland / Japan / New Zealand / Saudi Arabia / Sweden / United Kingdom / United States of America / Other (specify) |

3(b) | Which of these locations best describes your current place of practice? | University-affiliated tertiary hospital University-affiliated community hospital Non-university-affiliated community hospital Not practicing clinical medicine Other (specify) |

3(c) | What percentage of your current practice involves providing anesthetic care for pediatric patients? | |

3(d) | Please indicate your current subspecialty pediatric anesthesia practice area(s). (Check all that apply) | Cardiac anesthesia / Regional anesthesia Transplantation anesthesia / Palliative care medicine / Neuroanesthesia / Craniofacial / Orthopedic / Acute pain medicine / Chronic pain medicine / Other (specify) |

3(e) | Which of the following administrative positions do you hold, or have you held previously? (Check all that apply) | None / Undergraduate/Medical Student Coordinator / Residency Coordinator / Fellowship Coordinator / Subspecialty Clinical Director / Clinical Director / Associate/Assistant Departmental Chief / Departmental Chief / Other (specify) |

3(f) | Which of the following university appointments do you currently hold? | None / Lecturer / Assistant Professor / Associate Professor / Professor / Other (specify) |

4. Research | ||

4(a) | Have you completed formal research training? | None / Diploma / Master’s / PhD / Other |

If applicable, please describe specific discipline or type of research. | ||

4(b) | How many peer-reviewed research papers have you published since undertaking your general pediatric anesthesia fellowship? | |

5. Subspecialty training - Cardiac anesthesia | ||

5(a) | In your current practice, what percentage of your clinical practice is providing pediatric cardiac anesthesia? | |

5(b) | In your current practice, how many times a month do you provide anesthetic care for children with unrepaired or palliated congenital heart disease? | 0 / 1-5 / 6-10 / 11-15 / > 15 |

5(c) | In your current practice, how many times a month do you provide anesthetic care for children undergoing open heart surgery (with or without cardiopulmonary bypass)? | 0 / 1-5 / 6-10 / 11-15 / > 15 |

5(d) | How would you rate your ability to provide pediatric cardiac anesthesia? | Not competent / Competent / Proficient / Expert |

6. Subspecialty training - Regional anesthesia | ||

6(a) | In your current practice, how many times a month do you use any type of regional block in children? | |

6(b) | If you perform regional anesthesia in children, which of the following regional techniques do you consider yourself “expert” to perform? (Check all that apply) (Expert: I can skillfully perform this procedure, and I am very comfortable teaching it and problem solving any challenges with it.) | None / Caudal / Spinal / Paravertebral / Upper extremity blocks (interscalene, supraclavicular, infraclavicular, axillary) / Lower extremity blocks (femoral, sciatic, popliteal) / Trunk blocks (transverses abdominis plane or ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric) / Other (specify) / not applicable |

6(c) | If you perform regional anesthesia in children, which of the following regional techniques do you consider yourself “proficient” to perform? (Check all that apply) (Proficient: I can skillfully perform this procedure and rarely have to think about the steps or use a cognitive aid.) | None / Caudal / Spinal / Paravertebral / Upper extremity blocks (interscalene, supraclavicular, infraclavicular, axillary) / Lower extremity blocks (femoral, sciatic, popliteal) / Trunk blocks (transverses abdominis plane or ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric) / Other (specify) / not applicable |

6(d) | If you perform regional anesthesia in children, which of the following regional techniques do you consider yourself “competent” to perform? (Check all that apply) (Competent: I can perform this procedure but may have to think about the steps and/or use a cognitive aid.) | None / Caudal / Spinal / Paravertebral / Upper extremity blocks (interscalene, supraclavicular, infraclavicular, axillary) / Lower extremity blocks (femoral, sciatic, popliteal) / Trunk blocks (transverses abdominis plane or ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric) / Other (specify) / not applicable |

6(e) | For children, how do you rate your ability to use ultrasound to perform neuraxial anesthesia? | Not competent / Competent / Proficient / Expert |

6(f) | For children, how to you rate your ability to use ultrasound to perform peripheral nerve blocks? | Not competent / Competent / Proficient / Expert |

7. Subspecialty training - Pain medicine | ||

7(a) | In your current practice, what percentage of your clinical practice is providing acute pain management to children (outside of the OR)? | |

7(b) | For children, how to you rate your ability to manage acute pain? | Not competent / Competent / Proficient / Expert |

7(c) | In your current practice, what percentage of your clinical practice is providing chronic pain management to children (outside of the OR)? | |

7(d) | For children, how do you rate your ability to manage chronic pain? | Not competent / Competent / Proficient / Expert |

8. General pediatric anesthesia fellowship training | ||

8(a) | A 1-year general pediatric fellowship was adequate training to prepare me for independent practice in pediatric anesthesia. | Strongly agree / Agree / Neither agree nor disagree / Disagree / Strongly disagree |

8(b) | My current practice would have benefitted from a general pediatric anesthesia fellowship program longer than 12 months. | Strongly agree / Agree / Neither agree nor disagree / Disagree / Strongly disagree |

8(c) | In your opinion, which of the following pediatric anesthesia practice areas require more education and/or clinical exposure in the general pediatric anesthesia fellowship? (Check all that apply) | Cardiac anesthesia / Regional anesthesia / Transplantation anesthesia / Palliative care medicine / Neuroanesthesia / Craniofacial / Orthopedic anesthesia / Acute pain medicine / Chronic pain medicine / Other / None |

8(d) | During my general pediatric anesthesia fellowship, I was able to develop and refine my clinical teaching skills. | Strongly agree / Agree / Neither agree nor disagree / Disagree / Strongly disagree |

8(e) | During my general pediatric anesthesia fellowship, I acquired the necessary skills to carry out or support research activities. | Strongly agree / Agree / Neither agree nor disagree / Disagree / Strongly disagree |

8(f) | Which of these statements apply to your research experience during your general pediatric anesthesia fellowship? (Check all that apply) | I participated in research during my general pediatric anesthesia fellowship. I presented the results of research conducted during my general pediatric anesthesia fellowship at a national or international conference. My research conducted during my general pediatric anesthesia fellowship was published in a peer-reviewed journal. |

8(g) | How would you have improved your general pediatric fellowship program? | |

8(h) | In general, completion of 12 months of general pediatric anesthesia fellowship training is sufficient to allow anesthesiologists to provide safe anesthesia care for children. | Strongly agree / Agree / Neither agree nor disagree / Disagree / Strongly disagree |

8(i) | Completion of 12 months of general pediatric anesthesia fellowship training is sufficient to allow anesthesiologists to provide safe anesthesia care for INFANTS. | Strongly agree / Agree / Neither agree nor disagree / Disagree / Strongly disagree |

8(j) | Completion of 12 months of general pediatric anesthesia fellowship training is sufficient to allow anesthesiologists to provide safe anesthesia care for NEONATES. | Strongly agree / Agree / Neither agree nor disagree / Disagree / Strongly disagree |

8(k) | Any other feedback or comments on either general or subspecialty pediatric anesthesia fellowship training: | |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

O’Leary, J.D., Crawford, M.W. Perspectives on Canadian core fellowship training in pediatric anesthesia: a survey of graduate fellows. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 62, 1071–1081 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-015-0427-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-015-0427-7