Abstract

Street traders play a key role in the food system in South Africa and many other countries. Despite their importance, the operations of street traders are not well understood and often undermined by policy makers and planners. This article provides insights into the role of street traders who sell food, in particular fresh produce, and the nature of their operations. It shares experiences of street traders in South Africa since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic and derives lessons from this for their contribution to food and nutrition security. The article is based on in-depth research carried out with street traders and other food system actors that they are linked to in three provinces (Gauteng, KwaZulu Natal and Limpopo) of South Africa. It was found that the street traders were severely affected during the first hard lockdown and continued to suffer due to the drop in aggregate demand that has resulted from the reduced incomes of many of their clients. They have also not been able to access the government Covid-19 recovery funds. Despite these challenges, street traders have continued to perform an even more essential role in making fresh produce accessible. This is in contrast to supermarkets that have maintained higher prices and profit margins despite the state of disaster affecting people’s ability to buy. Street traders are deserving of greater recognition and support as they play a key role in achieving food security and addressing other socio-economic challenges. Improving the conditions for street traders requires securing more public space for food trading and recognising and building on the ways that street traders use space and organise their economic lives.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Street traders play a key role in making food accessible in South Africa, as they do in many other countries, yet they continue to receive little or no support and instead often face restrictions imposed by authorities (Battersby & Watson, 2018; Roever, 2014; Roever & Skinner, 2016; Skinner, 2018; Skinner & Haysom, 2016). These restrictions and the conditions for street traders and the informal sector in general became far worse during the Covid-19 pandemic (Battersby, 2020a; Rwafa-Ponela et al., 2022; Skinner & Watson, 2020b; Wegerif, 2020a). Research that has focussed on the impact of Covid-19 on street traders has tended to be based on small-samples and was only carried out over short time periods near the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic (e.g. Rwafa-Ponela et al., 2022; Wegerif, 2020a). This paper adds to existing work with a year of field research with street traders to reveal more in-depth information on how street traders selling foodFootnote 1 were affected and how they responded during the pandemic and how this compares to the formal food sector, in particular supermarkets. What happened in this crisis confirms and reveals more about the important contribution of street traders to food and nutrition security.

Understanding the contribution of street traders is essential given the context in South Africa, even before Covid-19, which includes massive inequality, unsustainable unemployment levels, poverty, and a high prevalence of food insecurity (Chatterjee et al., 2020; FAO et al., 2021; Stats SA, 2020). Many other countries face similar challenges and have street traders that can contribute more, but are often overlooked or undermined in their activities (Béné, 2020; Kiaka et al., 2021; Skinner, 2018). Lessons from this article, therefore, have relevance for improving food systems during and outside times of crisis in South Arica and beyond.

It is clear that the development challenges mentioned above were exacerbated by Covid-19 and the government responses to it. Millions of people lost incomes and this was overwhelmingly among the lower paid and women who started out with more precarious jobs (Spaull, Ardington et al., 2020; Spaull, Oyenubi et al., 2020). Unemployment in South Africa reached new highs with an official rate of 34.9%, but the more realistic expanded definitionFootnote 2 showing us that 46.6% of the labour force is out of work (Stats SA, 2021c). Before Covid-19 struck 44.9% of people in South Africa were moderately or severely food insecure and worryingly this was showing an upward trend over previous years (Stats SA, 2021b). Some studies are showing that food insecurity increased and continued to worsen through the different phases of the pandemic even after hard lockdown measures were lifted (Ngarava, 2022). It is too early to have accurate data on the long-term impacts of Covid-19 on food insecurity and outcomes like stunting, but all the indications and estimates are that it is going to get worse (FAO et al., 2021, 2022).

In the following section of this article, the qualitative research methodology used is explained. An overview of street traders is then provided before the elaboration of what the research found to be the most important impacts Covid-19 had on them. Out of what was found under the crisis conditions brought about by Covid-19, I identify lessons for the contribution of street traders to food and nutrition security. In doing this I use the six dimensions of food security, which have become more popular in recent years (FAO et al., 2022; HLPE, 2020) and focus in on the contribution of street traders to the dimensions of accessibility and agency. Taking a food system approach (Béné & Devereux, 2023; Devereux et al., 2020) I also explain some of the other socio-economic contributions of street traders found in the study, importantly the contribution to market demand for farmers’ produce and more equitable and dynamic local economies. The conclusion reiterates the main lessons and identifies possible pathways to maximizing the positive contribution of street traders.

2 Methodology

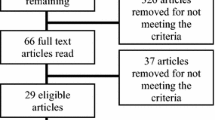

This article is based on new research carried out over 12 months from October 2020 to September 2021 and covered street traders’ experiences from the beginning of Covid-19 related regulations in March 2020 until the end of the research period when South Africa still operated under a national state of disaster with a range of restrictions in place. The research used qualitative and mixed methods approaches drawing on existing literature, secondary data, interviews, and observations (Denscombe, 2010; Denzin & Lincoln, 2008; Tracy, 2019). This research was carried out as part of a wider project - led by the Institute for Poverty Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS) at the University of the Western Cape (UWC) and funded by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) - on the impacts of Covid-19 on food systems in Ghana, Tanzania, and South Africa.

Fresh produce traders were chosen as the focus due to the large scale of street trader retailing of fruit and vegetables and the importance of fresh produce for balanced diets (FAO, 2020; Wegerif, 2020a). The perishability of the stock of these traders potentially makes them more vulnerable to disruptions compared to other traders selling processed and packaged foods or dry goods (Roever & Skinner, 2016), thus making understanding how they coped in a crisis situation of particular interest. Resource limitations prevented the inclusion of cooked food vendors which would have required a different sample group.

Core to this study were interviews with 39 street traders, - eight in Pietermaritzburg, KwaZulu Natal, ten in Limpopo, and 21 in the central business district (CBD) and a low-income residential area in Johannesburg, Gauteng - all of whom sell fresh produce, sometimes combined with selling other food and snacks. These comprised 29 women and ten men. Purposive, non-random, sampling (Denscombe, 2010) was used to find this diversity of research participants through the existing research, work and contacts of the participating organisations. We purposively covered the range of typical of street traders in South Africa in terms of their scale, nature of operations, and genders. The research sites covered three provinces and a variety of settlement types including a large city (Johannesburg), a medium sized city (Pietermaritzburg), rural and small-town areas in Limpopo, as well as residential and business locations.

The street traders were interviewed face-to-face where they sell using a questionnaire that gathered information on their business operations, how they started, and how Covid-19 affected them. During time spent with street traders, valuable conversations (Driessen & Jansen, 2013) were also held with some of their customers. Repeat visits and follow up unstructured interviews were carried out to get more and updated information on how the traders fared during Covid-19. All information gathering was conducted by members of the research team introduced in the acknowledgements section.

Key informants with knowledge of the fresh produce sector were also interviewed. These comprised 17 people including management and agents (who transact for a commission) at the municipal fresh produce markets, municipal officials, and officials from regulatory bodies such as the Agriculture Produce Agents Council. These were unstructured interviews, conducted face-to-face or on Zoom, involving extensive discussion of the fresh produce sector, the role of street traders, and the impacts of Covid-19.

Observation was carried out at the Johannesburg and Pietermaritzburg fresh produce markets and where street traders were operating in the research sites in all three provinces. This was to get a deeper sense of the functioning of the markets and the street trader operations including their relations with each other and customers (Tracy, 2019). While visiting research sites, field researchers made notes of what they saw of the environments as well as the operations of street traders and their relations with each other, customers, and other actors.

Reviews were done of existing research reports and academic articles related to street traders and urban food system governance, and various government agriculture strategies and municipal development plans. Existing data on prices was gathered from the National Agricultural Marketing Council (NAMC), and the South African Union of Fresh Produce Markets who compile retail and wholesale price information respectively.

Price checking was carried out in the Johannesburg CBD and Ivory Park, a low-income residential area also under the Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality. This was done by purchasing fresh produce items and weighing them to be able to compare per unit with supermarket prices and other data sets. We did not manage to systematise the frequency of price checking, in part due to Covid-19 disruptions. Nevertheless, samples were purchased from eight different street food traders (four in the Johannesburg CBD and four in Ivory Park), on 13 different occasions over more than a year. The prices and weights of these were compared with the same produce available at a supermarket on the same day, and with data from secondary sources mentioned above.

The interviews were analysed by the author with coding and spreadsheets used to identify the important characteristics of the traders, the impacts of Covid-19, the responses and experiences of the research participants, and other data. Data from the different sources (primary and secondary research) was analysed, compared, and combined in order to be able to present the experiences of street traders and identify lessons and conclusions that are shared below.

Ethical clearance for this research was obtained from both the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Western Cape, and the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Pretoria. This dual approval was due to the research being part of a joint project with researchers from both universities involved. The ethical clearance included approval of the methodological approach, including the questionnaires, conversations, observation, the process for obtaining informed consent from research participants, and the approach to dealing with Covid-19 risks. Covid-19 risks for researchers and research participants were minimised by observing the health guidelines set by the Department of Health in South Africa, primarily wearing of masks, maintaining a physical distance, and regular hand sanitising. Research participants were offered masks and hand sanitiser. Field research was also halted several times during waves of especially high Covid-19 infection rates.

The weaknesses of this study lie in the lack of a systematic approach to the price checking, and the small sample of research participants relative to the diversity of the sector and the geographic area covered. The strengths are in the in-depth research among street traders and the new information and perspectives that are shared from that with a focus on the specific experiences and contribution of street traders.

3 Street traders in South Africa: an overview

What are called street traders selling food in this article are micro-enterprises that sell fresh produce in public places. Most of them are owner operated although some do employ workers who take varying degrees of responsibility for the operations. Many sell on the sides of roads, whether intersections on busy roads or on suburban streets. Some sell in designated trading areas, on roads closed to traffic or small public market areas. Public transport nodes are also popular sites for street traders whose clientele are traveling to and from work or other businesses. These include bakkieFootnote 3 traders who buy directly from farms or from wholesale markets and sell on the side of the road to customers that include the general public and other street traders. Most of these bakkie traders span retail and wholesale roles, some more wholesale and some more retail orientated. All of these street traders fall under the category of what are often called ‘informal traders’ and the ‘informal sector’ (Chen & Carré, 2020).

Street traders in South Africa perform a similar function to street and public market traders in other parts of Africa, but an important difference is the very limited, almost non-existent, government approved public food markets (sometimes called wet-markets or traditional markets) in South Africa. This lack of public markets is a legacy of colonial and apartheid planning, which created a high level of racial and economic segmentation, both economically and geographically, followed by post-apartheid liberalisation of the economy that resulted in greater corporate domination and increased inequalities (Bond et al., 2014; Chatterjee et al., 2020). Public markets are far more common and play a more important role in the food systems of most other African countries and elsewhere in the world. South Africa’s food retail landscape, by contrast, is dominated by five main supermarket groups with stores normally located in privately owned shopping malls (CCSA, 2019).

Before Covid-19, statistics South Africa counted 2,921,000 people as working in the non-farm informal sector, accounting for 18.8% of all non-agricultural employment (Stats SA, 2020). This is an increase since Rogan and Skinner (2017) did an analysis of informal sector employment from 2008 to 2014 and found that it stayed between 16% and 18% of total non-agricultural employment, ending that period at 16.7%. It is worth noting that the nature of the sector – made up of enterprises not formally registered anywhere - is likely to lead to an undercounting of those involved and “is often underestimated and as a result, disregarded, even trivialized” (Skinner & Haysom, 2016: 2). There are no reliable figures that we could find for the scale of the informal food sector in South Africa, but it has been estimated that 67% of street traders sell food and that the informal sector accounts for around 30% of national food retail sales (Battersby et al., 2016). One of the large supermarket groups in South Africa has estimated that the informal food sector is worth as much as R360 billion ($24 billion) a year (Pick-N-Pay, 2019).

The focus in this study is on street traders who sell fresh produce. One of the main wholesale sources of this fresh produce are 17 municipal fresh produce markets spread across the country. These collectively had a turnover in 2021 of R17.91 billion ($1.19 billion) and R8.45 billion ($563 million) of that went through the Johannesburg Fresh Produce Market (JFPM) aloneFootnote 4. These are all municipal government owned entities, although they do have different management arrangements (Tempia et al., 2023). Municipal market agents interviewed for this study estimated that they sold 50–60% of their produce to the informal sector that street traders are a large part of. The Managing Director of the company that set up and operates the computer systems for the municipal markets, estimated that 60–70% of the sales are to the informal sector. It is hard to find accurate data on this due to a lack of clarity on what ‘informal’ is and the lack of any systematic capturing of data on the nature of the buyers at the municipal markets, but there is consensus that the informal sector accounts for a large part of the municipal market sales. If we take the lowest estimate of 50%, then informal traders are moving around R8.95 billion ($597 million) a year, plus their mark-up, of fresh produce from the municipal markets alone. On top of that there are other private markets and traders (including bakkie traders) who source a significant, but unquantified, amount of produce directly from farms.

The municipal markets highlight the interrelation between the formal and informal sectors. One can see at the JFPM, large trucks - mostly truck tractor combinations pulling two interlink trailers with loads of up to 56 tons – arriving through the night loaded with produce from the largest commercial farms in the country, but also carrying the produce aggregated from small-scale farmers. By sunrise most of the trucks have moved out and the JFPM yard is filled by an assortment of vehicles, dominated by one-ton bakkies, being loaded with produce bought by informal traders, often a number of traders sharing one bakkie. There are also larger trucks from some of the main supermarket groups and independent grocery stores collecting stock from the market. The intersection between the formal and informal continues beyond the market with street traders sourcing some of their stock from formal wholesalers and retailers (Skinner & Haysom, 2016). In this study we also found bakkie traders who supply formal shops and branches of the large supermarket groups with produce they get from municipal markets and directly from farms.

As well as moving a significant proportion of the fresh produce in the country, and therefore being important as a market outlet for farmers, street traders make fresh produce more accessible, especially to people with lower incomes. A recent study in low-income parts of Johannesburg found that while 90% of households used supermarkets, most did so only once per month. Local small shops and informal markets/street vendors were used by 85% and 35% respectively and these were used far more frequently than the supermarkets (Rudolph et al., 2021). Battersby et al. (2016) made similar findings in Cape Town with 94% of those surveyed using supermarkets, but far less frequently than they bought from informal markets/street vendors. This reflects a complex strategy of food acquisition by eaters in South Africa, with supermarkets being the main source for monthly purchases of core staples and other foods with a long shelf life, while local informal shops and street traders are the source for fresh produce and other daily purchases. The advantages of the fresh produce street vendors were identified as their convenient location, daily restocking, and often being cheaper than supermarkets (Battersby et al., 2016).

4 Impact of Covid-19

4.1 Initial lockdown

The first case of Covid-19 was confirmed in South Africa on the 5th of March 2020. With more Covid-19 cases confirmed in the following weeks the country was put into a national state of disaster in terms of the Disaster Management Act. Regulations were promulgated in terms of the Act to start a national lockdown for three weeks (later extended for a further two weeks) from midnight on 26th March 2020, with the aim of stopping the spread of the virus. People were ordered to stay in their homes unless going out to perform essential services or obtain essential goods and all businesses were ordered closed unless providing essential goods or services. Food was classified as an essential good and its production and retailing as essential services, but informal traders and open air markets were not allowed to operate even if selling food (COGTA, 2020). The result was the overnight closing down of all the street traders including those selling food. Many traders and their customers who we interviewed lost incomes and had to depend on friends, government grants, and charitable giving such as food parcels. Customers who had money were forced to go to supermarkets where they paid higher prices for fresh produce, with potentially negative impacts on diets as also identified by others analysing the impact of Covid-19 (Devereux et al., 2020). A perverse result was people spending more time and money traveling longer distances to get to supermarkets that were overcrowded and in some cases became hotspots for the spread of the Coronavirus (Evans, 2020; Kassen et al., 2020). After five weeks, the initial lockdown was relaxed and then strengthened and relaxed again several times in response to successive waves of Covid-19 infections. The state of disaster and its measures, such as social distancing requirements, curfews, and limits on public gatherings, remained in place until April 2022.

From a food security perspective, these initial Covid-19 restrictions completely undermined the agency of street traders, stopping their trade in food, and in the process limiting the agency of food eaters by limiting their choices in relation to food. This negatively impacted the livelihoods of street traders, threatening the food security of some of them (Skinner & Watson, 2020b), and limited access to food for eaters, thus undermining their food security. Interventions to prevent the spread of the coronavirus were needed, but these lockdown measures where prejudicial to street traders and their clients, with no good health reason, while allowing other food retailers, such as supermarkets, to continue operating. This reflects the undermining of the important role and agency of street traders by policy makers and planners, combined with an ‘anti-informality bias’ (Battersby, 2020b; Wegerif, 2020a). TiyiselaniFootnote 5, who sells fresh produce in Soweto, captured the views of many of the street traders interviewed, when she argued that “the government wants to help big business and forgot about us the little guys on the street. They are trying to stop the virus, but they don’t consider how the people they are trying to help live.”

Advocacy by trader organisations and civil society organisations (For example: Muller, 2020), supported by academics, did help to convince the government to amend the regulations, which they did on the 6th April 2020 (DSBD, 2020a). Street traders who sold uncooked food, such as fresh produce, were allowed to operate again, but a lot of damage had been done and it was not the end of unjustified state limitations on their activities. Those who sold cooked food continued to be banned from operating for some time. In May 2020 those cooking hot food were allowed to operate, but only for home deliveries (DSBD, 2020b). This provision of the regulations, much complained about by street traders, was later declared invalid by the Supreme Court of AppealFootnote 6.

Every one of the traders interviewed for this study had been completely stopped from trading in the first lockdown and it took weeks, for some of them months, to get back into operation. When the lockdown was announced traders tried selling the stock they had at reduced prices, but most still ended up losing a lot. Street traders operate with limited margins and limited reserves, relying on a daily cash turnover. In the weeks of not selling, all income stopped and traders had to deplete any capital they had in order to feed themselves and their families; a number of traders described this as eating their stock and their money. Starting again required using savings or borrowing money.

In April 2021, a year after she had been able to start trading again, Sylvia from Ivory Park told us that she still had not paid back all the money she borrowed to replace the stock she lost during the first lockdown. Many traders accumulated debt to survive and start operating again and then had to deal with a reduced market, as elaborated below, making the repayment more difficult. We were told by some of the traders of others they knew who had gone out of business.

4.2 Permit challenges

The requirement for traders to have permits from municipalities created further confusion and delays, with long queues at some municipal offices leading to the suspension of the issuing of permits (Ndlazi, 2020; Ntshidi, 2020; Sioga, 2020). Municipalities where not prepared for issuing such permits that had not been required before and were struggling themselves with how to operate under the Covid-19 conditions. In a typical example, Tiyiselani said she repeatedly went to the local municipality for three weeks, but was unable to get a permit because there was no clear understanding of how to issue permits or to who. Even when the processes went smoothly, the permit requirements disproportionately affected the smaller and owner operated enterprises, such as street traders, because without staff to delegate for such functions they had to shut their operations and lose business while going to apply. Providing the documents required for the permits was also more challenging for informal enterprises without offices and administrative staff. Many municipalities also first issued temporary permits that had to be renewed monthly, requiring more time and expenses for transport.

In addition to the permits required for trading, there was also a need for permits to allow people to travel, especially if moving between provinces. This affected bakkie traders who used to go to farms to buy. Livhuwani who used to buy directly from farms, told us how she had to have three different permits to operate, and getting each one took time and required her to provide a range of documents. Vonani got a permit and started to sell again, only to have his stock confiscated by the Johannesburg Metro Police who said he had to have another different permit. After signing an affidavit at the police station and queuing for three hours at the municipal office, Vonani got the second permit on the same day, but the police would not return his stock. He had to dig further into his saving to start again. Tsakani who sells in Tshwane said:

The metro police wanted permits and I did not have one so when they came to our section we were always running away and continued selling when they were gone. They would come on weekends, Saturdays especially to demolish our stalls.

4.3 Harassment continues

After some months, the new Covid-19 related requirements for permits were removed, and inter-provincial travel was allowed again (only temporarily re-imposed for Gauteng during the severe third wave of Covid-19). But, even under the trying conditions of a global pandemic and a national state of disaster, the harassment of street traders persisted. Ten of our 39 research participants reported being harassed by metro police and seven of them said that their stock had been confiscated.

Municipalities appeared, from the experiences of street traders, to step up their enforcement of by-laws under the pretext of enforcing continued Covid-19 related restrictions. As has been found in other African countries, the Covid-19 situation became an opportunity to renew efforts to “modernize the socio-spatial ordering of the city” through, among other activities, restricting street trading (Kiaka et al., 2021: 1). The Msunduzi Municipality, that includes the KwaZulu Provincial capital Pietermaritzburg, where a number of our research participants were from, issued notices in August 2021 saying that “it is illegal against municipal by-laws to operate trolleys within the street of Msunduzi Municipality”Footnote 7. Trolleys are important to many street traders as they are used to carry their stock, either to the place where they sell or to move around the streets selling directly from the trolley. The notice went on to say, “owners will bear the consequences” and ended with the justification that: “This is done to keep the city clean”.

The ‘clean’ city narrative is a perpetuation of a colonial and apartheid era argument frequently used as the motivation to keep black people out of South African (and other African) cities, unless they were there for specific approved work activities (Battersby, 2020a; Brown, 2015; Skinner & Watson, 2020a). The by-laws and planning ordinances being applied are also to a large extent a continuity of colonial practices that “embody older and European visions of what modern cities should be like” (Skinner & Watson, 2020a: 124). In a study of the responses to street traders in the South African city of Durban, Popke and Ballard (2004: 106) remind us that:

We should recall here that the production of urban modernity in South Africa relied in part upon a carefully regulated circulation of (non-white) bodies through urban space, producing a normalization of bodily comportment and social interaction. In its idealized form, the city could be ‘cleansed’ of unwanted bodies and activities, thereby normalizing the position of white South Africans as both subjects and agents of modern progress.

The Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality vigorously implemented their “High Density By-Law Operation” from August 2021, and it was still continuing more than a year later. During field research I witnessed an operation involving a convoy of at least seven Johannesburg Metro Police Department (JMPD) vehicles that included police cars, bakkies, and a truck to load up the goods, including food, confiscated from street traders. The JMPD boasted about the operation with regular tweets (@JoburgMPD) warning people against illegal trading and sharing pictures of the metro police confiscating goods. The tweets also repeatedly claimed the operations were to make the city “clean & safe”. While some of the JMPD tweets advised informal traders to apply for permits, traders we spoke to who did not have permits said they had applied and not been able to get them. One of the challenges is that there appears to be no designated space left available for new traders in the city, meanwhile the municipal development plans are not making provision for more public space for street traders.

4.4 Economic decline

Of the 39 street traders interviewed, 36 reported a decreased demand for their produce due to the economic conditions. The increased poverty and reduced buying power of customers continued throughout the pandemic and beyond. Despite recovering significantly after the devastating impact of the initial lockdown measures, South Africa’s economy in the second quarter of 2021 was still 1.4% smaller than the pre-Covid first quarter of 2020 (Stats SA, 2021a). The total number of people employed in the third quarter of 2021 was 14,282,000 (Stats SA, 2021c), down from the pre-Covid-19 number of 16,383,000 (Stats SA, 2020). This means that 18 months into the pandemic 2,101,000 (or 12.8%) fewer people were employed compared to the pre-pandemic situation. Importantly, this served to increase inequalities with the overwhelming number of jobs lost being among lower income earners (Spaull, Oyenubi et al., 2020), who are also the primary market for street traders. Trader after trader told us that people just don’t have money.

There was something of a reprieve for fresh produce sellers during the alcohol bans imposed as part of Covid-19 restrictions. Municipal market agents and several street traders told us that while alcohol was banned their sales were reasonable, but when the alcohol bans were lifted there was a significant drop in fresh produce sales. Jordan, who is a street trader in Pietermaritzburg, lamented that “it is as if the alcohol takes priority over food… when alcohol was banned people will buy the fruits or onions and go home. Now people are passing you by with a packet of beer.“

In addition to the impact of the overall economic decline, street traders have also lost customers due to changed working and shopping patterns and the closures of other businesses. Street traders in the CBDs of Johannesburg and Pietermaritzburg reported selling less stock and having to cut the number of workers they employed. With more people working from home, there are less workers coming to offices in the city centres. Shoppers have also moved to more online buying, thus reducing the footfall in some shopping areas and generating another source of competition in food retailing (UNCTAD, 2020). Traders in the Johannesburg CBD told us they lost more business when a large supermarket and other retail stores closed. This indicates the complexity of relations, including perhaps interdependence, between large-scale formal enterprises and street traders. I also observed how, with workers and customers no longer coming to these stores, fewer people were stopping to buy from the street traders on their way home or on lunch breaks.

In this context of economic decline, street traders have been attempting to keep their prices low. Vonani showed us the R3 ($0.20) packets of onions he was preparing and explained that “people don’t have money, money is not there, there are no jobs now, you must think about the people”. He told us he has to change price when the prices go up at the market or he is losing money, but he also said, “you will chase the customers away if you make the price too high”. When there were particular spikes in prices, such as when wholesale tomato prices almost doubled in April 2021 due to weather related crop damage, street traders were selling at around the cost price or with very thin margins. They did not feel they could push the prices higher. Mrs Dlamini, who sells a variety of fresh vegetables in Pietermaritzburg, said that:

Although producers have raised prices across, I did not increase my prices here because I am a religious person who sell to the poorest of the poor so increasing prices would really kill them since many have lost jobs. Why should we increase a price when we do make enough profit? We need to be considerate and God will bless us.

4.5 Formal sector failing the poor

A full appreciation of the contribution of street traders is not possible outside the context food price inflation and without some comparison with supermarkets that dominate food retailing in South Africa. Analysis of core and food price inflation for the first 18 months since the outbreak of Covid-19 in South Africa - using the monthly Statistics South Africa P0141 Statistical Releases – showed that food inflation was higher than core inflation every month for an average core inflation rate of 3.58% compared to a 60.5% higher average food price inflation of 5.75%. The Essential Food Pricing Monitoring report (reports introduced to track the pandemic’s impact on food markets), released by the Competition Commission South Africa (CCSA) in August 2021, highlighted an increasing concentration of food production and ownership in fewer corporate hands. The report also showed how during the Covid-19 pandemic, food prices had continued rising faster than core inflation and food security was threatened (CCSA, 2021). In a radio programme discussing the report, the Competition Commission’s Chief Economist explained that the big corporations “can immunize themselves from cost pressures” by putting downward pressure on the prices paid to farmers and passing higher costs on to consumers. Examples of how this has worked for corporations can be seen in the increased profits and returns to shareholders achieved during the Covid-19 pandemic by the largest food company in South Africa, Tiger Brands, and the largest supermarket group, Shoprite. Tiger Brands reported that earnings per share were up 123% in the six months to the end of March 2021, compared to the equivalent six months before Covid-19 affected South Africa. A lot of the benefit of that must have gone to the company’s largest single shareholder, which is a United Kingdom based investment firm (Tiger Brands, 2021). Shoprite increased profits on its South African supermarket operations by 17.2% and its headline earnings per share by 20.3% for the 53 weeks to 4th July 2021 (Shoprite, 2021).

The ability of the formal sector to maintain high margins can be clearly seen in fresh produce prices. For the first 18 months of the Covid-19 restrictions, from April 2020 to end September 2021 (the last month we had figures for at the time of writing), the gap between the wholesale price of tomatoes at the JFPM and the average formal sector retail price, was 156%. For onions that gap was 292%, a difference of almost three times between the wholesale and retail prices (Table 1). The fresh produce was available at the JFPM and other municipal markets at these wholesale prices, and the formal sector retailers do source at these markets as well as through more direct supply chains. The formal sector retailers did not necessarily increase their margins in percentage terms, but they did sustain these high margins – resulting in Rand increases in the inflationary environment - even as the country went through a national disaster. What this data also shows is that the cost of the municipal market operations, as reflected in the commissions paid there, are a relatively minor part of the total retail cost of the food.

Comparing the prices in Table 1 and the street traders’ prices in Table 2, one can see that the street traders sell at around the mid-range, between the wholesale and formal sector retail prices. Further, when there were spikes in the prices of particular produce, it appears that the street traders absorbed some of the additional costs, shielding their customers who they knew did not have money. This is also reflected in some of the comments made by street traders, such as that by Mrs Dlamini shared above. Formal food outlets, on the other hand, were quick to push up their retail prices to maintain their margins when wholesale prices rose. For example, due to bad weather average per kg prices for tomatoes in April 2021 were R15.71 at the JFPM, roughly double the average for the year. NAMC reported retail prices at over R30 in April, while our sample of tomatoes from a street trader in April cost R15.52 a kg. The approach of supermarkets can also be seen in the example of the supermarket group Shoprite which increased its margins and profits during the pandemic (Shoprite, 2021). This wholesale to retail gap highlights the important role that the municipal markets and street traders play in making fresh produce accessible. This is the economic gap street traders are taking and it is a potential opportunity for the sector to grow if they can be allowed to trade more widely.

4.6 Resilience of street traders

The quarterly labour force surveys produced by Statistics South Africa (statistical releases P0211) show that, after being very hard hit in the second quarter of 2020 (when the lockdown was introduced), the informal sector bounced back and by the end of the third quarter of 2021 (end September 2021) had recovered 65% of the jobs lost, while the formal sector had, instead of recovering, lost even more jobs. This left formal sector employment down by 14.7% since the outbreak of Covid-19 and the informal sector down by 7.7% (Stats SA, 2021c). Street traders, including those who are self-employed, form part of those counted as employed in the informal sector. Unfortunately, the available statistics do no differentiate street traders and the informal food sector from the wider informal sector. It is too early to make firm conclusions and to know if these trends will continue, but it does seem that, unlike in the financial crisis of 2008 (Rogan & Skinner, 2017), the informal sector is showing resilience and becoming an alternative source of employment during this crisis. Of total non-agricultural employment, the proportion of those employed in the informal sector had increased to 20% by the end of September 2021, compared to the pre-Covid-19 figure of 18.8% 2020Footnote 9.

It was reported that 3,000 new buyers registered at the JFPM in the first two months after lockdown. This included Patrick who had been employed as a driver for six years and was retrenched in the first months of the Covid-19 restrictions. He now buys fresh produce at the JFPM and sells it from the back of his bakkie in a middle-class part of Johannesburg where there were no fresh produce sellers before. Patrick positioned himself a block from a mall, he says they will move him if he goes closer. He keeps his stock on the back of his bakkie ready to pull a cover over it if the police arrive. Through these tactics he has set up business and nine months later is becoming an established feature of the neighbourhood. Another example is Thembi who lost her job as a domestic worker when Covid-19 struck South Africa. She is now employed by a bakkie trader to sell fresh produce for him in a street in Pietermaritzburg. She is earning more than she did as a domestic worker and her new employer, unlike the previous one, helps her with money for transport to get from home to where she sells. Other street traders shared that they now support partners or other family members who lost jobs in the formal sector.

4.7 Government support

None of the traders in our study received any specific business support from the government or any other organisations. Calls on the government, made during the first lockdown, to provide some form of restart packages went unheeded (Skinner & Watson, 2020b; Wegerif, 2020a). Some of our research participants had applied for various business support packages, but none were successful. Themba, a bakkie trader from Pietermaritzburg said, “we didn’t see any assistance from the government because most of initiatives included requirements like proof of business addresses which were all impossible for us.“ A group of traders in Limpopo were told by officials from the local municipality that they would get R3,500 grants to assist them. They provided all their names and other required information but received nothing. Seven of the traders in our sample managed to get either the R350 ($23) per month social relief of distress grants or benefitted from the top up applied to child grants they were already receiving. Four of the traders had also applied for food parcels, but none received them. Pheladi from Tshwane said, “I know we once signed up for food parcels and never got them”, she added that with all her relatives at home now, out of work and school, the food finishes quickly.

The lack of support received by these traders is in contrast to the grand sounding support packages that the government spoke about, such as the R500 billion ($33.3 billion) relief fund announced by the President on the 21st April 2020 (Ramaphosa, 2020).

5 Lessons about the contribution of street traders

5.1 Contribution to food and nutrition security

The widely used definition of food security is “[a] situation that exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” (FAO et al., 2022: 202). There are six dimensions that have been identified as necessary for achieving food security. These are: availability; accessibility; utilization; stability (short-term); sustainability (long-term); and agency. Of these six, sustainability and agency are fairly recently suggested as additions to the other four dimensions (FAO et al., 2022; HLPE, 2020).

Following this framework, street traders’ largest contribution to food security is through making food more accessible, especially fresh produce that is essential for a healthy diet (FAO, 2020). Street traders are a significant supplier, especially in poorer neighbourhoods, of nutrition, protein and energy in South Africa and across most African countries (Skinner & Haysom, 2016; Steyn et al., 2014). We argue, based on the research for this article, that street traders are also an interesting example of the importance of agency in ensuring food security.

Based on our primary research, and in line with other literature on the wider informal food sector (e.g. Battersby et al., 2016; Skinner & Haysom, 2016), we find that street traders in particular, even during the crisis times of the Covid-19 pandemic, make food more accessible than other retailers through: (1) low prices; (2) selling in flexible and small quantities to fit buyers needs and ability to pay; (3) selling at locations close to where people live, work or travel; (4) selling on interest free credit to people they know and trust. The focus here on street traders during a pandemic, and the elaboration below of how they contribute to food accessibility, adds value to existing literature and arguments by confirming some of them and bringing new insights. The reflections on the dimension of agency in relation to street traders contributes to our understanding of this newly conceptualised dimension of food security.

5.1.1 Low prices

The price checking and comparisons carried out indicate that street traders continued (thus contributing to stability of supply), aside from when stopped from operating under the first weeks of the hard lockdown, through the Covid-19 pandemic to sell fresh produce at prices substantially below the prices in supermarkets and other formal retail outlets. Across basic food items of onions, tomatoes, potatoes, and cabbage we found that prices were between 77% and 103% more expensive in the supermarkets than bought from street traders on the same days (Table 2). The differences were even larger on some other items, such as robot (red, yellow, and green) peppers. Onions, tomatoes, and cabbage are used extensively in everyday cooking in South Africa, primarily as an affordable relish eaten with the staple maize porridge. While there is very consistent price data collected from formal retail outlets and wholesale markets, there is currently no such data set from street traders. Despite weaknesses in the sampling, there is a clear indication from our findings in Gauteng Province of the order of magnitude of the price differences between street traders and supermarkets.

Studies in other countries have also found this ability of ‘traditional’ retailers - including street traders -, linked to wholesale markets, to sell fresh produce at significantly lower prices than supermarkets (Guarín, 2013; Tschirley et al., 2004).

Based on what we have seen in this study, the reasons for higher prices in the supermarkets appear to be related to extraction of profits for shareholders, management overheads, advertising costs, tax provisions, and property overheads. In comparison, street traders, as owner operated enterprises, have no management overheads, extract no profits for distant investors, and spend nothing on advertising. Street traders also avoid the overhead costs of renting space to trade and owning property as they use the public space of the streets; access to this space being essential to the nature and success of their businesses. The low incomes of street traders also contribute to their low costs and prices (CCSA, 2019; Guarín, 2013; Shoprite, 2021; Wegerif & Martucci, 2019).

More research and analysis could usefully be done on price and cost structures of street trader and supermarket operations, as well as on food safety issues. Whatever the reasons for the higher prices of fresh produce in supermarkets, our main point is that the street traders are selling fresh produce at lower prices, thus making healthy diets more accessible.

5.1.2 Selling small quantities

The small size and the flexibility of quantities sold by street traders, with no price penalty, is important for buyers with limited incomes. By comparison, supermarkets typically practice regressive pricing in the form of charging less per unit for larger quantities, while having higher per unit prices on smaller quantities. This, like regressive taxes, favours the rich - who have more disposable income and more storage space and facilities like fridges - at the expense of the poor - who don’t have the money or the availability of storage facilities to enable buying and keeping of larger quantities (Skinner & Haysom, 2016). In our price comparison, we bought small quantities of each item from street traders and we found that the pricing per unit remained the same regardless of how small a quantity was bought; even down to being able to buy one onion or one tomato if wanted. Some street traders, especially in residential areas, also make convenient combinations for common dishes made by their clients. For example, packaging a quarter cabbage and a few carrots for making coleslaw.

5.1.3 Selling at locations close to where people live, work, or travel

Other studies, such as in Epworth Zimbabwe (Tawodzera, 2023) and the Kanana informal settlement in South Africa (Skinner & Haysom, 2016), have identified that location is one of the key factors determining food buying decisions, including decisions to buy frequently from informal food sellers that are close by. Street traders in our study typically sell either close to where people live, or where they work, or at transport intersections. These sites make the street trader accessible without the need for any extra travel time or cost. In residential areas, such as Ivory Park where we did research, we found street traders on many streets ensuring no one had to walk more than a few minutes to reach them. In addition, we found trolley traders moving door to door selling fresh produce they carried on trolleys. Street traders close to where people work, such as in the CBDs of Johannesburg and Pietermaritzburg, are accessible in lunch breaks or as people move to and from work. At transport intersections, such as the taxi ranks and bus terminals, we observed in all our study sites how people traveling already for other purposes can pick up what they need from the street trader, including from trolley traders.

5.1.4 Selling on credit

Street traders selling food on credit was a common practice among many of our research participants and helps people access food when they have no cash available. The credit is extended based on trust and knowing the person as a regular customer, as has been found in other literature on the informal food sector in South Africa and other parts of Africa (Battersby et al., 2016; Skinner, 2016; Skinner & Haysom, 2016). It is more common in residential areas as the street traders, who normally live in the areas where they sell, know most of their customers. It is understandably less common among traders in business areas and at transport nodes where there is greater anonymity and more passing customers. Credit can be as simple as ‘pay me tomorrow,’ when someone doesn’t have money with them at the time. It is often also linked to the timing of people’s incomes. Street traders explained how people run out of money in the middle of the month, they then take food on credit and pay when they get their salaries or receive state grants that are paid monthly. As one customer, Mihle, explained it, with reference to a street trader called Gloria and her table of produce, “I survive here, yah, she has got a book, I take credit.” Gloria demonstrated on subsequent visits just how well she knew Mihle, updating me on how he was doing after he lost his job due to Covid-19 and telling us when he had found a new job. With this knowledge of their clients, traders will also refuse to provide on credit if they believe the person will not or cannot repay them.

Another street trader, Patrick, explained that people take credit in the middle of the month when they start to run out of money. When asked if he charges more if selling on credit, he said “I can’t do that, I am suffering, also the people are suffering, if I do that it is wrong. If I do that to people they will go somewhere else”. In these few words Patrick not only explained his thinking on credit, but also clearly explained the logic observed in how street traders operate. They are combining the application of norms of what is right and wrong, a sense of solidarity with people they know, and the business sense that keeping prices low and extending credit keeps customers loyal and coming back.

5.1.5 Agency

The exercise of their agency and the creation of an environment within which they can do so are key to the role of street traders. They take individual actions to start their enterprises, taking over public spaces that are accessible to their customers, and in the process providing more choices (opportunities to exercise agency) for those customers. In the South African context of few designated public spaces for street traders, street traders operate in a grey and contested area on the edge of legality, pushing and expanding the boundaries of what they can get away with.

One of the main challenges to street traders is the obstruction of this exercising of agency by state authorities, mostly in the form of municipal police, using a range of forms of harassment including trying to move them or confiscate their stock (Roever, 2014). This obstruction of agency by the state was highlighted by the Covid-19 disaster regulations, as elaborated in other parts of this article. Street traders exercise their agency not so much through recognised organisations or open protest, but more often with ‘every day forms of resistance’ (Scott, 1985) and ‘quiet encroachment’ (Bayat, 2000). This involves ‘cat and mouse’ tactics of occupying, expanding and reordering space, retreating when needed only to return again when the coast is clear and negotiating relations with those in authority that harass them, but also take bribes and are at times customers (Kiaka et al., 2021).

5.2 Creators of markets for farmers

With their combined buying power, street traders are essential to the functioning of the municipal markets and through the markets they create demand for the produce from farms large and small (Tempia et al., 2023). In addition, street traders (especially the bakkie traders) buy directly from farms, including large commercial farms. They are also a particularly important market for small- and medium-scale black farmers as, when buying directly from the farmers, they pay better prices, they pay cash, and there are no transport costs for the farmer. Some black farmers also adapted by selling more to street traders after they lost other markets during the Covid-19 pandemic (Wegerif, 2022).

5.3 Contribution to local communities and economies

In a strong example of what has been referred to as being socially embedded (Granovetter, 1985), street traders either live within the communities where they sell or in other low-income neighbourhoods not far away. They form part of and contribute to the social and economic fabric of these communities. Living with and understanding the people they sell to, and the nature of their face-to-face interaction with their clients, creates a greater opportunity for empathy, which has been found to be a facilitator of markets that are fair and effective (Zak, 2011). The street traders and their clients tend to operate within common cultural repertoires, with a sense of familiarity, and with a level of interdependence that has been described elsewhere as symbiotic relations (Wegerif, 2018, 2020b). The social connection with their customers is illustrated by the nature of interactions that we observed in this research project, such as the way that street traders typically greet and are greeted by the clients in various indigenous South African languages, using the terms for sister, brother, uncle, aunt, or mother. While one may find a customer greeting a supermarket cashier as ‘sister’, the cashier is not the owner of the supermarket, whereas the street trader is the owner and decision maker in their enterprise. As such, the street trader can be negotiated with and the familiarity between the trader and their customers has the possibility of affecting traders’ decisions.

Recognising these social relations is not intended to undervalue the importance of market factors, such as price that I have given a lot of attention to above. The empathy of street traders is always balanced by a level of self-interest and ‘marketness’, which should not be seen as negative as it is essential for their economic success (Hinrichs, 2000).

As other studies have found (Giroux et al., 2020; Roever, 2014), we saw how, through their networks, street traders make an important contribution to other parts of the local economy and society. The street trader spends more within the same community through purchasing from other local businesses and paying for services, such as for transport, porters, and security - thus adding to the economic multiplier affects and local economic activity. One trader explained how she gives work to unemployed young people from where she lives: “I usually ask them to come assist me at the stall so that they can earn an income to buy bread or something to eat at home.”

5.4 Low barriers to entry for inclusive economies

Low barriers to entry are critical to the ubiquitous nature of street trading and why it is important as a business opportunity for people in poverty (or close to it). The street as a public space that can be accessed at no, or a very low, cost is central to the logic of street traders. They are asserting rights to this common pool resource through their actions in order to secure their livelihoods (Brown, 2015). The traders in our study either paid nothing, or a limited amount for trading permits, to use the spaces where they traded.

The street traders interviewed did not start out with any large amounts of capital, typically they began with just a few hundred Rand, bought small quantities of produce, and then expanded. Information and assistance from others are also essential elements of how most start. Vonani, who now employs three workers selling a wide range of produce from his stall in the Johannesburg CBD, explained how he started:

My friend, he showed me how to buy… I started with three bags of potatoes, then onions, then tomatoes and then more. I never borrowed money from anyone. When you buy for R500 and make R700, then you buy again for R700, and then again buy with all the money, it grows like that.

Sylvia, who sells in Ivory Park, said that: “I started to buy one box of tomatoes and one bag of potatoes and then thereafter I add add add”. Being able to buy the small quantities these traders started with - which Vonani got at the JFPM and Sylvia at the Tshwane Fresh Produce Market - at low prices, and being able to share transport with others when collecting stock, were other essential ingredients for getting into business.

Street trading is an important business opportunity for hundreds of thousands of people in South Africa and should not be looked down on as merely survivalist or just an activity of last resort. Given the economic realities, street trading is for many a better option than the others they have and for some it is seen as joining the family business. Lucy, who sells in Tshwane, said “I used to work at the Chinese clothing shop on the other side and I stopped because people told me that they made a lot of money from selling in the streets and I started selling too.“ Another woman in Tshwane explained that she was a domestic worker and she decided to leave that job in order join her mother as a street trader. Several traders told us how they started while still at school helping their mothers who were street traders and then later took over the businesses or started their own stalls.

More than half of our sample had been street traders for over ten years and some for over 30 years, indicating that it is a serious business and career. Livhuwani who sells in the CBD of Johannesburg, explained the importance of her business as a street trader: “I am surviving by this business. Yes, because all my children I sent to school by this business and then [my] first born [child] is going university for this business and now is done [graduated from university]”. Tsakani, a street trader in Tshwane said:

This was my first job. I used to assist my mother here when I was still at school. My mother used to sell cooked food on the other side of the taxi rank to earn an income to raise us. I learnt a lot from her and continued the business to also provide for my children. This table, never undermine it because it takes a lot of children to school.

5.5 Undermined by decision makers

Unfortunately, street trading is consistently undermined in South Africa through a combination of neglect in policy making and development planning combined with active criminalisation by law enforcement operations. The “Agriculture and Agro-processing Master Plan (AAMP) Draft version 05, January 2021” does mention the importance of the informal sector, but says nothing specific about street traders or bakkie traders. The same lack of attention to the important role of street traders was clear in a South African national consultation, held on 22nd July 2021, in preparation for the United Nations Food System Summit (DALRRD et al., 2021). The event, convened by the Minister responsible for Agriculture, gave a lot of attention to how farmers could be integrated into corporate value chains, but said nothing at all about street traders. Street traders selling food are equally invisible in the Integrated Development Plan and Spatial Development Framework 2040 for Johannesburg, South Africa’s largest city. The only food market space mentioned in these plans is the JFPM. Attention to the JFPM is welcome given its importance, but it is incredible that the traders who account for at least 50% of the sales at the JFPM are not considered. Equally worrying is that the plans for this city of 5.7 million people spread over 1 645 km² only make provision for one public food market.

The neglect of street traders in development planning and policies is in contrast to the high-level of attention they are subjected to in law enforcement and city clean-up operations. Harassment by authorities, largely municipal security forces, has been identified around the world as one of the most important constraints on street traders’ businesses. This often takes place even when traders have licences (which are not easy to get) and takes forms such as demanding bribes, evicting traders, and confiscation of their stock (Kiaka et al., 2021; Roever, 2014; Roever & Skinner, 2016). In our study it emerged that different municipalities have different approaches to the issuing of permits, with procedures simply unclear in some cases. There are also differences within municipalities; notably there is far less enforcement of by-laws in low-income neighbourhoods and a more rigorous removal of traders in wealthier suburbs. This at least allows street traders to supply low-income communities, but it also cuts them off from the opportunity to compete for wealthier customers. One of the main constraints to getting trading permits that our research participants reported was the lack of approved space for which trading permission is given.

6 Conclusion

The initial Covid-19 lockdown measures in South Africa were devastating for street traders leaving many still struggling to fully recover more than a year later. Their economic recovery and their on-going operations were made harder by the harsh economic environment that Covid-19 caused along with changing working and buying patterns and the lack of government support. Despite all the challenges, including many people suffering reduced incomes, street traders have continued to operate and have sold fresh produce at prices, in quantities, and at locations that make food more accessible for those in poverty. By contrast, most food corporations have been able to protect, even increase, their profits and returns to shareholders. The responsiveness of street traders to their clients’ situation is shaped by the close contact and familiarity between them and based on an interdependence that combines a sense of solidarity with the self-interest of a businessperson who knows their survival depends on the client coming back. This is important in the context of millions of people losing jobs and incomes and food price increases beyond core inflation rates.

Some street traders have been pushed out of business, others have had to retrench employees, but the sector as a whole showed resilience, thus contributing to stability in the food system. Street trading has become a refuge for many people who have lost jobs in the formal sector and have turned to street trading to secure their livelihoods. Whether this shift will continue and if it will result in fiercer competition amongst street traders that, while good for consumers, could negatively affect individual incomes is in part dependent on government actions and whether interventions are made to enable the sector as a whole to expand. While street traders’ incomes are often low, especially at these times, they are still higher for many than they would get from the other options available to them, as confirmed by some of our research participants who have moved from formal sector employment to street trading. Importantly, as a sector with low barriers to entry and multitudes of owner operated enterprises, street trading has the potential, if well supported, to contribute to overcoming the unsustainable levels of unemployment and inequality in South Africa.

The experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic have confirmed that street traders selling food perform essential functions in the food system. These include making fresh produce more accessible, which contributes to greater food security, and creating livelihoods for themselves and others with a high contribution to local economic development. Despite this, street traders are overlooked in government policies and development plans and subjected to harassment by local authorities, in particular metro police. The undermining of street traders and the lack of understanding of their operations (or bias against them) was highlighted by how they were shut down during the first weeks of the Covid-19 lockdown and then faced new permit requirements and harassment that were obstacles to them returning to business. Even after the new permit requirements were relaxed, authorities appeared to be using the Covid-19 conditions to intensify their campaigns for ‘clean’ and ‘modern’ cities and in the process criminalising people’s efforts to lift themselves out of poverty.

Overcoming these negative approaches requires further research and ongoing data gathering to create a better understanding of the scale and nature of the street trading sector. More systematic data collection on street traders’ food prices would be a useful part of this. Such research needs to focus on learning from the way street traders use space and organise to create and recreate their economic lives (Hart, 2015; Skinner & Watson, 2020a). Other issues of interest, touched on but not elaborated in this article, that could benefit from further research include the relationship between alcohol consumption and food buying and the complex interrelation between street traders and the formal sector.

Access to public space - in the street, on the pavements, and in more designated public markets - is central to the operations of street traders, yet this is largely overlooked in current development and spatial plans. Policy and planning changes are needed to create far more public food markets, and more space in the streets, accessible for street traders and their clients. This needs to include space to trade within the wealthier neighbourhoods that street traders continue to be largely excluded from but into which the sector could expand if given the opportunity. Such space needs to be recognised within revised legal frameworks that treat it as a common pool resource available for people to conduct business and secure their livelihoods (Brown, 2015).

The experiences of street traders during the Covid-19 pandemic in South Africa has demonstrated the importance of agency as a dimension of food security. The violation of the agency of street traders undermined food security for the traders and their customers. Instead of being worked with as part of the solution to the crisis situation of Covid-19, they were treated as part of the problem. Recognising and enabling their agency, with interventions that value and build on their existing operations, is going to be essential to ensuring food security and dealing with disasters in the future. This requires a fundamental change of approach to food systems, urban planning, and regulation. It requires that we break away from colonial continuities, to instead adopt an approach that is “bottom-up, incremental, flexible, economically conversant and acutely aware of, and informed by, the specific context and power dynamics” (Skinner & Watson, 2020a: 130). This needs to be carried out in a participative way, that experiments, considers the interests of the variety of different users of space, involves ongoing learning, and adjusts along the way. Such planning needs to be responsive to the ‘quiet encroachment’ (Bayat, 2000) of street traders, not criminalising it, but rather respecting it as an important way in which those who are not included in the official policy and planning processes express their needs and demonstrate what works for them.

Notes

For the sake of brevity, we will in places refer to street traders or traders to mean, unless otherwise specified, street traders selling food. We don’t use the term street food traders, because that is generally used to refer to those selling cooked food. Due to the focus of the study and limitations of time and resources, the traders in this study are primarily selling uncooked fresh produce.

This includes those who want work, but have given up looking, indicated by not actively look for work in the four weeks before being surveyed.

Bakkie is a South African term for a small, normally one-ton capacity, pickup truck.

This calculated from monthly statistical reports provided by the South African Union of Food Markets.

Tiyiselani is a research participant being referred to with the use of a pseudonym, as are all other such people referred to in this way.

The prohibition on selling cooked food, other than for home delivery, was subject to legal action and in January was declared invalid by the Supreme Court of Appeal in case: Esau and Others v Minister of Co-Operative Governance and Traditional Affairs and Others (611/2020) [2021] ZASCA 9; [2021] 2 All SA 357 (SCA); 2021 (3) SA 593 (SCA) (28 January 2021).

This was from a public notice posted by the Municipality.

The total commission is 12.5%, made up of 7.5% to the agent and 5% to the market.

During the research the exchange rate was approximately R15 to $1USD.

References

Battersby, J. (2020a). Looking backward to go forward. Gastronomica: The Journal for Food Studies, 20(1), 19–20. https://doi.org/10.1525/gfc.2020.20.1.19.

Battersby, J. (2020b). South Africa’s lockdown regulations and the reinforcement of anti-informality bias. Agriculture and Human Values, 37, 543–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-020-10078-w.

Battersby, J., & Watson, V. (2018). Urban Food Systems Governance and Poverty in African cities. Routledge.

Battersby, J., Marshak, M., & Mngqibisa, N. (2016). Mapping the invisible: the Informal food economy of Cape Town, South Africa (Urban food security series, Issue. https://hungrycities.net/publication/hcp-discussion-papers-no-5-mapping-informal-food-economy-cape-town-south-africa/.

Bayat, A. (2000). From ‘Dangerous classes’ to quiet rebels’ politics of the Urban Subaltern in the Global South. International Sociology, 15(3), 533–557. https://doi.org/10.1177/026858000015003005.

Béné, C. (2020). Resilience of local food systems and links to food security–A review of some important concepts in the context of COVID-19 and other shocks. Food Security, 12(4), 805–822.

Béné, C., & Devereux, S. (2023). Resilience and Food Security in a Food systems Context. Springer Nature.

Bond, P., Garcia, A., & Garcia, A. (2014). Elite Transition-revised and expanded Edition: From Apartheid to Neoliberalism in South Africa. Pluto Press.

Brown, A. (2015). Claiming the streets: Property rights and legal empowerment in the urban informal economy. World Development, 76, 238–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.07.001.

CCSA (2019). The Grocery Retail Market Inquiry Final Report. http://www.compcom.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/GRMI-Non-Confidential-Report.pdf.

CCSA (2021). Essential Food Pricing Monitoring: August 2021. https://www.compcom.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/EFPM-Report_Aug-2021.pdf.

Chatterjee, A., Czajka, L., & Gethin, A. (2020). Estimating the distribution of household wealth in South Africa (9292568027). https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/229269/1/wp2020-045.pdf.

Chen, M., & Carré, F. (2020). The Informal economy revisited: Examining the past, envisioning the future. Routledge.

COGTA (2020). Regulation No. R. 398. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202003/4314825-3cogta.pdf.

DALRRD, U. N., & AUDA. (2021). &. Leveraging Public-Private Partnerships Towards Scaling Up Food Systems Solutions in South Africa During and Beyond Covid-19 (UN Food Systems Summit 2021: Republic Of South Africa’s Synthesis Dialogue, Issue.

Denscombe, M. (2010). The good research guide: For small-scale social research projects (4th Edition ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2008). The Discipline and Practice of qualitative research. Sage Publications, Inc.

Devereux, S., Béné, C., & Hoddinott, J. (2020). Conceptualising COVID-19’s impacts on household food security. Food Security, 12(4), 769–772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01085-0.

Driessen, H., & Jansen, W. (2013). The hard work of small talk in ethnographic fieldwork. Journal of Anthropological Research, 69(2), 249–263.

DSBD (2020b). Regulation No. R. 522. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202005/43306rg11109gon522.pdf.

DSBD (2020a). Regulation No. R. 450. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202004/43208rg11081gon450.pdf.

Evans, J. (2020). 16th April 2020). Covid-19: Outbreaks at supermarkets a concern for Western Cape government. News24. Retrieved 27 April, 2020 from https://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/covid-19-outbreaks-at-supermarkets-a-concern-for-western-cape-government-20200416.

FAO. (2020). Fruit and vegetables – your dietary essentials. The International Year of fruits and vegetables, 2021, background paper. Food and Agriculture. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb2395en. Organisation of the United Nations.

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, & WHO. (2021). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021: Transforming Food Systems for Food Security, Improved Nutrition and Affordable Healthy diets for all. Food and Agriculture Organisation. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb4474en. of the United Nations.

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, & WHO. (2022). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021: Repurposing Food and Agricultural policies to make healthy diets more affordable. Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc0639en.

Giroux, S., Blekking, J., Waldman, K., Resnick, D., & Fobi, D. (2020). Informal vendors and food systems planning in an emerging African city. Food Policy, 101997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101997.

Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2780199.

Guarín, A. (2013). The value of domestic supply chains: Producers, wholesalers, and urban consumers in Colombia. Development Policy Review, 31(5), 511–530. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12023.

Hart, K. (2015). Human Economy: The Revolutionary struggle for happiness. In K. Hart (Ed.), Economy for and against Democracy (2 vol., pp. 201–220). Berghan Books.

Hinrichs, C. C. (2000). Embeddedness and local food systems: Notes on two types of direct agricultural market. Journal of Rural Studies, 16, 295–303.

HLPE (2020). Food security and nutrition: Building a global narrative towards 2030. CFS - Committee on World Food Security. http://www.fao.org/3/ca9731en/ca9731en.pdf.

Kassen, J., Felix, J., & Brandt, K. (2020). Over 200 Western Cape Supermarket Employees Test Positive for Coronavirus. Eye Witness News. Retrieved 27 April, 2020 from https://ewn.co.za/2020/04/25/over-400-western-cape-supermarket-employees-test-positive-for-coronavirus.

Kiaka, R., Chikulo, S., Slootheer, S., & Hebinck, P. (2021). The street is ours. A comparative analysis of street trading, Covid-19 and new street geographies in Harare, Zimbabwe and Kisumu, Kenya. Food Security, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-021-01162-y.

Muller, R. (2020). Message from President of SAITA on the effects of COVID-19 to the informal business economy. Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing. Retrieved 25 December from https://www.wiego.org/resources/message-president-saita-effects-covid-19-informal-business-economy.

Ndlazi, S. (2020). 7 May 2020). Tshwane Informal traders frustrated at being denied permits. Pretoria News. https://www.iol.co.za/pretoria-news/tshwane-informal-traders-frustrated-at-being-denied-permits-47653648.

Ngarava, S. (2022). Empirical analysis on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on food insecurity in South Africa. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth Parts A/B/C, 127, 103180.

Ntshidi, E. (2020). COJ To Give Details On The Continuation Of Issuing Permits For Informal Traders. EWN. https://ewn.co.za/2020/04/08/coj-to-give-details-on-the-continuation-of-issuing-permits-for-informal-traders.

Pick-N-Pay (2019). Integrated Annual Report. http://www.picknpayinvestor.co.za/downloads/investor-centre/annual-report/2019/iar-2019.pdf.