Abstract

Background

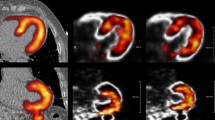

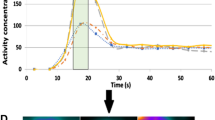

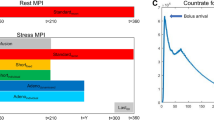

Patient motion has been demonstrated to have a significant impact on the quality and accuracy of rubidium-82 myocardial perfusion PET/CT. This study aimed to investigate the effect on patient motion of two pharmacological stressing agents, adenosine and regadenoson.

Methods and Results

Dynamic data were retrospectively analyzed in 90 patients undergoing adenosine (n = 30), incremental adenosine (n = 30), or regadenoson (n = 30) rubidium-82 myocardial perfusion PET/CT. Severity of motion was scored qualitatively using a four-point (0-3) scale and quantitatively using frame-to-frame pixel shifts. The type of motion, returning or non-returning, and the frame in which it occurred were also recorded. There were significant differences in both the qualitative and quantitative scores comparing regadenoson to adenosine (P = .025 and P < .001) and incremental adenosine (P = .014, P = .015), respectively. The difference in scores between adenosine and incremental adenosine was not significant. Where motion was present, significantly more adenosine patients were classed as non-returning (P = .018). The median frames for motion occurring were 12 for regadenoson and 14 for both adenosine cohorts.

Conclusions

The choice of stressing protocol impacts significantly on patient motion. Patients stressed with regadenoson have significantly lower motion scores than those stressed with adenosine, using local protocols. This motion is more likely to be associated with a drift of the heart away from a baseline position, coinciding with the termination of infusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- AV:

-

Atrioventricular

- BIF:

-

Blood input function

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- LAD:

-

Left anterior descending

- LVM:

-

Left ventricular myocardium

- MBF:

-

Myocardial blood flow

- OSEM:

-

Ordered-subset expectation-maximization

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- TAC:

-

Time-activity curve

References

Ziadi MC, DeKemp RA, Williams K, Guo A, et al. Does quantification of myocardial flow reserve using rubidium-82 positron emission tomography facilitate detection of multivessel coronary artery disease? J Nucl Cardiol 2012;19:670–80.

Murthy VL, Naya M, Foster CR, et al. Improved cardiac risk assessment with non-invasive measures of coronary flow reserve. Circulation 2011;124:2215–24.

Prior JO, Allenbach G, Valenta I, Kosinski M, et al. Quantification of myocardial blood flow with 82Rb positron emission tomography: Clinical validation with 15O-water. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2012;39:1037–47.

Lortie M, Beanlands R, Yoshinaga K, Klein R, DaSilva J, deKemp R. Quantification of myocardial blood flow with 82Rb dynamic PET imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2007;34:1765–74.

Kaufmann PA, Camici PG. Myocardial blood flow measurement by PET: Technical aspects and clinical applications. J Nucl Med 2005;46:75–88.

Tout D, Tonge CM, Muthu S, Arumugam P. Assessment of a protocol for routine simultaneous myocardial blood flow measurement and standard myocardial perfusion imaging with rubidium-82 on a high count rate positron emission tomography system. Nucl Med Commun 2012;33:1202–11.

Hunter CRRN, Klein R, Beanlands RS, de Kemp RA. Patient motion effects on the quantification of regional myocardial blood flow with dynamic PET imaging. Med Phys 2016;43:1829–40.

Presotto L, Gianolli L, Gilardi MC, Bettinardia V. Evaluation of image reconstruction algorithms encompassing Time-Of-Flight and Point Spread Function modelling for quantitative cardiac PET: Phantom studies. J Nucl Cardiol 2015;22:351–63.

Koshino K, Watabe H, Enmi J, Hirano Y, et al. Effects of patient movement on measurements of myocardial blood flow and viability in resting 15O-water PET studies. J Nucl Cardiol 2012;19:524–33.

McCord ME, Bacharach SL, Bonow RO, Dilsizian V, et al. Misalignment between PET transmission and emission scans: Its effect on myocardial imaging. J Nucl Med 1992;33:1209–14.

Rajaram M, Tahari AK, Lee AH, et al. Cardiac PET/CT misregistration causes significant changes in estimated myocardial blood flow. J Nucl Med 2013;54:50–4.

Woo J, Tamarappoo B, Dey D, Nakazato R, et al. Automatic 3D registration of dynamic stress and rest 82Rb and flurpiridaz F 18 myocardial perfusion PET data for patient motion detection and correction. Med Phys 2011;38:6313–26.

Mohy-ud-Din H, Karakatsanis NA, Goddard JS, Baba J, et al. Generalized dynamic PET inter-frame and intra-frame motion correction—Phantom and human validation studies. In: IEEE nuclear science symposium and medical imaging conference (NSSMIC) 2012. p. 3067–78.

Klein R, Renaud JM, Ziadi MC, Thorn SL, et al. Intra- and inter-operator repeatability of myocardial blood flow and myocardial flow reserve measurements using rubidium-82 PET and a highly automated analysis program. J Nucl Cardiol 2010;17:600–16.

Naum A, Laaksonen MS, Tuunanen H, Oikonen V, et al. Motion detection and correction for dynamic 15O-water myocardial perfusion PET studies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2005;32:1378–83.

Armstrong IS, Tonge CM, Arumugam P. Impact of point spread function modeling and time-of-flight on myocardial blood flow and myocardial flow reserve measurements for rubidium-82 cardiac PET. J Nucl Cardiol 2014;21:467–74.

Cerqueira MD, Verani MS, Schwaiger M, Heo J, et al. Safety profile of adenosine stress perfusion imaging: Results from the adenoscan multicentre trial registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994;23:384–9.

Cerqueira MD. The future of pharmacological stress: Selective A2A adenosine receptor antagonists. Am J Cardiol 2004;94:33D–40D.

Iskandrian AE, Bateman TM, Belardinelli L, et al. Adenosine versus regadenoson comparative evaluation in myocardial perfusion imaging: Results of the ADVANCE phase 3 multicenter international trials. J Nucl Cardiol 2007;14:645–58.

Iqbal FM, Hage FG, Ahmed A, Dean PJ, et al. Comparison of the prognostic value of normal regadenoson with normal adenosine myocardial perfusion imaging with propensity score matching. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;5:1014–21.

Zahid M, Kapila A, Eagan CE, Yusko DA, et al. Prevalence and significance of electrocardiographic changes and side effect profile of regadenoson compared with adenosine during myocardial perfusion imaging. J Cardiovasc Dis Res 2003;4:7–10.

Zhao G, Linke A, Xu X, Ochoa M, et al. Comparative profile of vasodilation by CVT-3146, an novel A2A receptor agonist, and adenosine in conscious dogs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2003;307:182–9.

Trouchu JN, Zhao G, Heiner P, Xu X, et al. Selective A2A adenosine receptor agonist as a coronary vasodilator in conscious dogs: Potential for use in myocardial perfusion imaging. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2003;41:132–9.

Lieu HD, Shryock JC, von Mering GO, Gordi T, et al. Regadenoson, a selective A2A adenosine receptor antagonist, causes dose-dependent increases in coronary blood flow velocity in humans. J Nucl Cardiol 2007;14:514–20.

Wilson RF, Wyche K, Christensen BV, Zimmer S, et al. Effects of adenosine on human coronary arterial circulation. Circulation 1990;82:1595–606.

Gao Z, Li Z, Baker SP, Lasley RD, et al. Novel short-acting A2A adenosine receptor agonists for coronary vasodilation: Inverse relationship between affinity and duration of action of A2A agonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2001;298:209–18.

Watt AH, Routledge PA. Adenosine stimulates respiration in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1985;20:503–6.

Lassen ML, Rasmussen T, Christensen TE, Kjaer A, Hasbak P. Respiratory gating in cardiac PET: Effects of adenosine and dipyridamole. J Nucl Cardiol 2016. doi:10.1007/s12350-016-0631-z.

Acknowledgements

The authors would also like to acknowledge the work by Andy Bradley, Ian Armstrong, and Heather Williams in assisting with the collection of historical data for assessing the incidence of patient motion.

Disclosure

There are no conflicts of interest for Matthew J. Memmott, Christine M. Tonge, Kimberley J. Saint, or Parthiban Arumugam.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Memmott, M.J., Tonge, C.M., Saint, K.J. et al. Impact of pharmacological stress agent on patient motion during rubidium-82 myocardial perfusion PET/CT. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 25, 1286–1295 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12350-016-0767-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12350-016-0767-x