Abstract

Introduction

This study aims to assess the risk of direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) discontinuation among Medicare beneficiaries with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) who reach the Medicare coverage gap stratified by low-income subsidy (LIS) status and the impact of DOAC discontinuation on rates of stroke and systemic embolism (SE) among beneficiaries with increased out-of-pocket (OOP) costs due to not receiving LIS.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, Medicare claims data (2015–2020) were used to identify beneficiaries with NVAF who initiated rivaroxaban or apixaban and entered the coverage gap during ≥ 1 year. DOAC discontinuation rates during the coverage gap were stratified by receipt of Medicare Part D Low-Income Subsidy (LIS), a proxy for not experiencing increased OOP costs. Among non-LIS beneficiaries, incidence rates of stroke and SE during the subsequent 12 months were compared between beneficiaries who did and did not discontinue DOAC in the coverage gap.

Results

Among 303,695 beneficiaries, mean age was 77.3 years, and 28% received LIS. After adjusting for baseline differences, non-LIS beneficiaries (N = 218,838) had 78% higher risk of discontinuing DOAC during the coverage gap vs. LIS recipients (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.78; 95% CI [1.73, 1.82]). Among non-LIS beneficiaries, DOAC discontinuation during coverage gap (N = 91,397; 34%) was associated with 14% higher risk of experiencing stroke and SE during the subsequent 12 months (aHR, 1.14; 95% CI [1.08, 1.20]).

Conclusion

Increased OOP costs during Medicare coverage gap were associated with higher risk of DOAC discontinuation, which in turn was associated with higher risk of stroke and SE among beneficiaries with NVAF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Reduced adherence and persistence of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) use are associated with increased risk of poor clinical outcomes including increased risk of stroke and systemic embolism (SE) among Medicare beneficiaries |

Increased out-of-pocket (OOP) costs that Medicare beneficiaries experience during the Medicare coverage gap phase may lead to reduced adherence and persistence of DOACs |

We examined the implications of increases in OOP costs during the Medicare coverage gap on patterns of DOAC use and incidence of stroke and SE among beneficiaries with non-valvular atrial fibrillation |

What was learned from this study? |

Medicare beneficiaries not receiving financial assistance via the low-income subsidy (LIS) had a significantly higher risk of discontinuing DOACs compared to those receiving subsidies to shield them from increased OOP costs, which subsequently increased the risk of serious cardiovascular events (stroke and SE) |

Reducing shifts in cost sharing burden could minimize medication discontinuation and improve overall health of vulnerable populations |

Introduction

Newer branded direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), including rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran, have been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events (CVEs), such as stroke and systemic embolism (SE), and mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) [1,2,3]. The reduced risk resulting from DOAC use is dependent upon adherence and persistence to the medication. Prior research has found that suboptimal adherence and persistence with DOACs is common, with one in three patients demonstrating adherence to their DOACs < 80% of the time [4, 5], which in turn are associated with poor clinical outcomes including increased risk of stroke and SE [4].

Recent real-world evidence has shown that adherence and persistence to DOACs are particularly low among Medicare beneficiaries [6, 7]. Many Medicare beneficiaries receive prescription drug coverage through Medicare Part D. These plans have a feature called the coverage gap in which beneficiaries are required to pay a substantial share of their drug costs until they reach a prespecified yearly maximum for out-of-pocket (OOP) drug spending (“catastrophic threshold”). Once beneficiaries reach the catastrophic threshold, they are responsible for paying the greater of either the maximum amount for generic or brand-name drugs, or 5% of the total drug cost [8]. With the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the cost sharing burden on beneficiaries has been reduced. Nonetheless, beneficiaries continue to experience high OOP costs during the coverage gap, which has been associated with cost-related non-adherence and discontinuation of drugs [9,10,11]. In contrast, studies have shown that Medicare beneficiaries who receive “Extra Help” through the Low-Income Subsidy (LIS), which reduces or eliminates this cost sharing burden during the coverage gap, are less likely to reduce adherence to or discontinue their medications compared to beneficiaries who did not receive “Extra Help” during the coverage gap [12,13,14].

This study aims to build upon the existing literature by highlighting the implications of potential increases in OOP costs during the Medicare coverage gap phase for patterns of DOAC use and incidence of stroke and SE among beneficiaries with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF). In particular, the study addresses the following objectives: (1) assess DOAC discontinuation rates after reaching the coverage gap stratified by the receipt of LIS, a proxy for not experiencing increased OOP costs, among Medicare beneficiaries with NVAF who reached the coverage gap and (2) evaluate the impact of DOAC discontinuation during the Medicare coverage gap on rates of stroke and SE during the subsequent 12 months among Medicare beneficiaries with NVAF who did not receive LIS, and therefore experienced an increase in OOP costs. Consistent with prior studies [14], LIS status was selected as a proxy for increased OOP costs as opposed to using OOP costs directly, since post-ACA, availability of LIS is the key mechanism for reduced OOP burden during the coverage gap for beneficiaries with otherwise similar profiles. Indeed, in our exploration of OOP costs before and during the coverage gap, we found that those receiving LIS did not experience a change in their OOP costs during the coverage gap whereas those not receiving LIS did (see Supplementary Material—Table S2).

Methods

Data Source

The 100% Medicare Fee-For-Service (FFS) data in the Standard Analytical File (SAF) format were used, including Parts A, B (1/1/2015–12/31/2020), and D (1/1/2015–12/31/2019). The data use agreement was approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) [15]. The data contained information on beneficiary demographics, diagnostic and procedure codes, medications dispensed, dates of service, place of service, type of provider, and costs paid by Medicare. The data were de-identified and complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964; therefore, an institutional review board (IRB) exemption was obtained per Title 45 of CFR, Part 46.101(b)(4) (18) from WCG IRB.

Study Design

A retrospective observational design was used. Beneficiaries newly initiating rivaroxaban or apixaban—the two most commonly used DOACs for treatment of NVAF in the US—in 2015–2019 and entering the coverage gap during at least one calendar year after treatment initiation, as identified via the “Benefit Phase” and “Catastrophic Coverage Code” variables in the Part D data files, were included in the study.

Study Populations

For both objectives, beneficiaries were included in the study if they met the following criteria: (1) ≥ 1 dispensing of rivaroxaban or apixaban in 2015–2019; (2) ≥ 1 inpatient (IP) NVAF diagnosis or ≥ 2 outpatient (OP) NVAF diagnoses before the first claim for rivaroxaban or apixaban; (3) reached the Medicare coverage gap after the first dispensing of rivaroxaban or apixaban in at least one calendar year during the study period; (4) ≥ 65 years of age on index date (described below); (5) continuous enrollment in Medicare Part A, B, and D ≥ 6 months prior to and ≥ 1 month after the index date.

For objective 1, beneficiaries were classified into either the LIS cohort if they received LIS in the calendar year leading up to or during the coverage gap or the non-LIS cohort elsewise (index date = start of coverage gap). For objective 2, the non-LIS cohort was further classified into two sub-cohorts: the discontinue cohort, including those who discontinued DOACs before exiting the coverage gap (index date = date of discontinuation), and the non-discontinue cohort otherwise (index date = end of coverage gap). Based on clinical input, discontinuation was defined as the earliest of the following events: (1) a gap of at least 30 days in the days of supply for DOACs between the end of a dispensing and the next fill; (2) a gap of at least 30 days in the days of supply for DOACs between the end of a dispensing and the end of follow-up period; (3) a switch to generic warfarin with no additional fills for DOACs for at least 30 days after the switch. Switches between rivaroxaban and apixaban or to other DOACs (e.g., edoxaban, betrixaban, and dabigatran) were not considered discontinuation events.

For both objectives, the baseline period spanned 6 months prior to the index date. For objective 1, the follow-up period spanned from the index date to the earliest date of treatment discontinuation, end of coverage gap, or data availability (Supplementary Material—Fig. S1). For objective 2, the follow-up period spanned from the index date to the earliest date of the end of 12 months after index date or end of data availability (Supplementary Material—Fig. S2).

Beneficiaries were excluded from all analyses if they met any of the following criteria to minimize confounding: (1) ≥ 1 claim for warfarin use during baseline; (2) ≥ 1 diagnosis of stroke or SE during the 30 days prior to or on the index date; (3) ≥ 1 claim for mitral stenosis, mechanical heart-valve procedure, organ/tissue transplant, hip or knee replacement, or venous thromboembolism (VTE) during the baseline period; (4) ≥ 1 diagnosis of renal failure or end stage renal disease (ESRD), or kidney transplant, or cancer during the baseline period. In addition, to increase the likelihood that beneficiaries were using DOACs while entering the coverage gap, beneficiaries with no evidence of DOACs use in the 30 days prior to the coverage gap were excluded. Furthermore, for objective 2, beneficiaries with dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid during baseline period and 1 month after index date were also excluded.

Measures

Baseline Characteristics

Beneficiary characteristics measured during the baseline period for both objectives included demographics (i.e., age, gender, region of residence, and race), year of index date, baseline comorbidity scores (i.e., the congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes mellitus, prior stroke or TIA or thromboembolism, vascular disease, age, sex category [CHA2DS2-VASc] [16], and the hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function, stroke, bleeding history or predisposition, labile international normalized ratio [INR], elderly [age ≥ 65 years], drugs/alcohol concomitantly [HAS-BLED] score [17], Quan-Charlson comorbidity index [CCI] [18]), stroke and SE risk factors (i.e., arrhythmia, hypertension, coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and smoking), medication use (e.g., cardiovascular-related medications and anti-hyperglycemic agents), all-cause healthcare costs, months of follow-up, duration of DOAC treatment prior to index date, and month of entering the coverage gap.

Follow-Up Outcomes

For Objective 1, time to DOAC treatment discontinuation was assessed and compared between LIS and non-LIS cohorts. For Objective 2, the following event rates were assessed and compared between discontinuation cohorts during the follow-up period: a composite outcome of stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) and SE, stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic), and SE. The stroke and SE outcomes were defined based on primary or secondary diagnosis codes in a hospital or emergency department setting.

Statistical Analysis

For both objectives, baseline characteristics were summarized descriptively using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and relative frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. Stratified cohorts were compared using standardized differences (SD); SD > 10% was considered statistically relevant.

In addition, for objective 1, multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the relative hazard of discontinuing treatment during the coverage gap by LIS status, adjusting for differences in following baseline characteristics: age, sex, index year, region, comorbidities, cardiovascular medicine use, Quan-CCI score, total costs, and duration of DOAC treatment.

For objective 2, Kaplan-Meier analyses were conducted to assess the time from index to incidence of stroke and SE during the follow-up period. Statistical significance of difference in the outcomes between beneficiaries who did and did not discontinue DOACs during the coverage gap was assessed using a log-rank test. Furthermore, regression techniques were used to determine the statistical significance of differences in outcomes adjusting for baseline differences. First, sampling weights were estimated using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW)—a propensity score-based method that implemented a multinomial logistic regression to model the likelihood scores of discontinuation cohort assignment with baseline characteristics (described in objective 1) used as model predictors [19]. The weights were adjusted for sample size to account for leverage issues [20]. Weighted baseline characteristics were then compared between cohorts using SDs to assess balance. In the second step, Cox proportional hazards models with doubly robust estimation were performed on the IPTW-weighted sample to compare discontinuation rates between the discontinue and non-discontinue cohort with adjustment for any residual confounding from the IPTW that could impact cohort assignment or outcomes. Note, the CHA2DS2-VASc score was not included in the doubly robust model since the list of variables that were included in the IPTW model and, subsequently, the Cox model includes several variables that are associated with increased risk of stroke and systemic embolism during the follow-up period and were also used in the calculation of the CHA2DS2-VASc score, including hypertension and stroke during the baseline period. Inclusion of CHA2DS2-VASc score in addition to these variables could result in collinearity, which would in turn reduce the precision of the estimates. All analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide version 7.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

For objective 1, 303,695 beneficiaries were included in the study population, with 84,857 beneficiaries in the LIS cohort and 218,838 beneficiaries in the non-LIS cohort (Supplementary Material—Fig. S3). The mean age at the start of coverage gap was 77.3 years (Table 1). Beneficiaries had an average of 9.1 months of DOAC treatment. A higher proportion of non-LIS cohort was White (92.8% vs. 69.6%), male (47.5% vs. 35.0%), and had entered the coverage gap in July to December (81.4% vs. 65.2%). The non-LIS cohort was generally healthier compared to the LIS cohort, with lower mean CHA2DS2-VASc (3.8 vs. 4.5), HAS-BLED (2.2 vs. 2.5), and Quan-CCI scores (1.0 vs. 1.8) and less use of anti-hyperglycemic agents (15.2% vs. 21.7%). The prevalence of several comorbidities and risk factors for stroke and SE was also lower among non-LIS cohort, including complicated hypertension (10.8% vs. 16.9%) and peripheral artery disease (9.2% vs. 18.6%). However, heart arrythmia was more prevalent in the non-LIS cohort than the LIS cohort (83.9% vs. 76.8%). Baseline total healthcare costs were lower among the non-LIS cohort relative to the LIS cohort ($7593 vs. $11,115).

For objective 2, 270,405 beneficiaries were included in the study population, with 91,397 beneficiaries in the discontinue cohort and 179,008 beneficiaries in the non-discontinue cohort (Supplementary Material—Fig. S4). Before IPTW (Table 2), compared to the non-discontinue cohort, the cohort that discontinued DOAC during the coverage gap had higher comorbidity burden and medical resource use as well as longer duration of DOAC treatment (all SD > 10%). After IPTW, demographic characteristics were more comparable at baseline, although the discontinue cohort continued to have higher comorbidity indices (CHA2DS2-VASc: 3.8 vs. 3.7; HAS-BLED: 2.2 vs. 2.1; Quan-CCI score: 1.2 vs. 1.0), higher total costs ($9404 vs. $7159), and longer duration of DOAC treatment (19.9 vs. 13.5 months) (all SD > 10%).

DOAC Discontinuation Stratified by LIS Status

A higher proportion of non-LIS cohort discontinued DOAC during coverage gap (18.2% vs. 10.6%) (Table 4), and while similar proportions re-initiated rivaroxaban or apixaban over time, a lower proportion did so in the same calendar year after exiting the coverage gap compared to the LIS cohort (5.2% vs. 25.1%, p < 0.001) (Supplementary Material—Table S1). After adjusting for selected baseline differences including age, sex, index year, region, Quan-CCI score, cardiovascular medicine use, total costs, and duration of DOAC treatment, the risk of discontinuing DOACs during the coverage gap was 78% higher among beneficiaries who did not receive LIS compared to those receiving LIS (hazard ratio [HR]; 1.78; 95% CI [1.73, 1.82]) (Table 3).

Incidence of Stroke and Systemic Embolism by DOAC Discontinuation

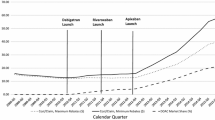

Kaplan-Meier estimates of incidence of stroke or SE in the 12 months post-index were numerically higher among the discontinue cohort relative to the non-discontinue cohort (Fig. 1). Specifically, 2.6% of the discontinue cohort had a composite outcome of stroke and SE during the entire follow-up period compared to 2.2% of the non-discontinue cohort. Similarly, the rates of stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) and SE were 2.5% and 0.2% during the entire follow-up period among the discontinue cohort compared to 2.1% and 0.1% among the non-discontinue cohort (data not shown).

Kaplan-Meier curves for time to stroke and systemic embolism stratified by discontinuation statusa–d. The dashed gray line corresponds to all patients, the dark blue line corresponds to discontinuers, and the light blue line corresponds to non-discontinuers. DOAC direct oral anticoagulant, IQR interquartile range. aThe index date was defined as the date of DOAC treatment discontinuation for beneficiaries who discontinued and the end of the coverage gap for beneficiaries who did not discontinue. The end of the coverage gap was defined as the earliest of the start of catastrophic coverage phase, end of calendar year, and end of data availability. bThe follow-up period was censored at the earliest of 12 months after index date and end of data availability. cDiscontinuation was defined as having any of the following: (1) treatment gap ≥ 30 days between observed fills, (2) treatment gap ≥ 30 days between last observed fill and end of observation period, (3) switching to generic warfarin. dAcross the entire follow-up period, the Kaplan-Meier rates of experiencing stroke and systemic embolism were 2.6% for discontinuers and 2.2% for non-discontinuers (p < 0.001)

After adjusting residual differences in doubly robust model (Table 4), including age, sex, index year, region, select comorbidities, cardiovascular medicine use, Quan-CCI score, total costs, and duration of DOAC treatment, beneficiaries who discontinued DOACs during the coverage gap had 14% higher risk of stroke and SE (HR, 1.14; 95% CI [1.08, 1.20]), 12% higher risk of stroke (HR, 1.12; 95% CI [1.06, 1.18]), and 48% higher risk of SE (HR, 1.48; 95% CI [1.20, 1.82]), compared to beneficiaries who did not discontinue DOACs.

Discussion

This large-scale retrospective cohort study among Medicare beneficiaries with NVAF found that beneficiaries in the non-LIS cohort (i.e., those with increased OOP costs) had 78% higher risk of discontinuing DOAC during coverage gap compared with similar beneficiaries in the LIS cohort (i.e., those without increased OOP costs), implying that adherence and persistence to DOAC were lower among beneficiaries who had a sudden coverage-gap driven increase in their OOP costs. Indeed, in our exploration of OOP costs before and during the coverage gap, we found that those receiving LIS did not experience a change in their OOP costs during the coverage gap whereas those not receiving LIS did (Supplementary Materials—Table 2). Specifically, beneficiaries receiving LIS do not experience a change in their OOP costs after entering the coverage gap ($89 ± $507 pre vs. $98 ± $1962 during the gap), whereas those not receiving LIS do ($592 ± $7439 pre vs. $1390 ± $31,715 during the gap). Importantly, beneficiaries who discontinued DOACs had significantly higher hazards of experiencing stroke and SE compared to beneficiaries who did not discontinue DOACs, further suggesting that reducing OOP costs during Medicare coverage gap could improve clinical outcomes among beneficiaries with NVAF.

Recent studies have similarly reported that beneficiaries without financial assistance were more likely to discontinue medications and reduce adherence, which in turn could result in negative outcomes [14, 21,22,23]. Of particular relevance to this study, Zhou et al. compared anticoagulant use and health outcomes associated with Medicare Part D plan coverage of NOACs and found that beneficiaries whose drug plans restricted DOAC coverage had worse adherence and higher risk of mortality/stroke/transient ischemic attack compared to beneficiaries whose plans do not restrict DOAC use (HR, 1.10; 95% CI [1.08, 1.12]) [23]. Similarly, a recent systematic review included three retrospective studies in people with AF and reported that DOAC nonadherence was associated with increased risk of stroke (HR, 1.39; 95% CI [1.06, 1.81]), and DOAC non-persistence was associated with increased risk of stroke/transient ischemic attack (HR, 4.55; 95% CI [2.80, 7.39]) [4]. Collectively, the findings from the present study further underscore that even a short period of DOAC discontinuation before exiting the Medicare coverage gap (approximately 77 days) has a substantial impact on the risk of stroke and SE events among beneficiaries with NVAF. Of note, the risk of strokes and SE in this study may be underestimated as a large proportion of beneficiaries (63.4%) discontinuing DOACs during the coverage gap re-initiated DOACs after exiting the coverage gap or potentially switched to warfarin. Given the high associated cost of stroke/SE events, structuring health payment systems to reduce OOP costs for patients taking DOACs could both improve clinical outcomes of patients with NVAF and produce cost-savings associated with averted stroke/SE events [24,25,26,27].

Recent policy changes have aimed to reduce OOP costs for Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Part D plans. Specifically, the ACA of 2010 and the Bipartisan Budget Act (BBA) of 2018 included provisions to gradually phase out the coverage gap between 2019 and 2020 by shifting a higher proportion of the cost sharing burden to manufacturers and insurers and reducing beneficiary coinsurance to 25% [28]. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 also included new provisions to lower prescription drug costs and reduce drug spending [29]. Key features included provisions to cap OOP costs for Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Part D plans and expand eligibility for full benefits under the Part D LIS program beginning in 2024 [29]. Although the data for this study began after the implementation of the ACA, additional research is needed to better understand the implications of other recent policies on prescription drug use patterns and subsequent outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries with NVAF.

Using longitudinal data for a representative population enrolled in the 100% Medicare FFS and robust statistical methods, our study findings corroborate existing literature on the excess disease burden imposed by the Medicare coverage gap and other coverage restrictions among beneficiaries requiring chronic medication. Nonetheless, the results must be interpreted in the context of common limitations associated with observational claims-based studies. First, as analyses of administrative claims data depended on correct diagnosis, procedure, and drug codes, the identification of stroke and SE might be subject to coding inaccuracies and data omission. Second, the lack of electronic medical record data precluded inclusion of certain clinically relevant metrics such as disease severity. Third, while results in Supplemental Table 2 showed that non-LIS beneficiaries experienced higher costs than LIS beneficiaries before, during, and after the coverage gap, directly confirming that the beneficiaries discontinued/switched treatment due to higher OOP costs was impossible. The data also did not contain information on over-the-counter medications (e.g., aspirin) which might be used for prophylaxis in combination with or in place of DOACs as part of anticoagulant treatment. Fourth, the data did not contain details on other socioeconomic factors that might affect the outcome (e.g., household income). While efforts were made to reduce the degree of variability due to socioeconomic factors (such as by excluding LIS-eligible patients in objective 2), residual confounding because of unobservable factors could impact effect estimates. Lastly, the study population comprised Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older; thus, the findings might not be generalizable to all US beneficiaries with NVAF, such as beneficiaries enrolled in Medicaid or patients without health insurance.

Conclusions

Findings of this real-world study demonstrate that not receiving LIS and consequently facing increased OOP costs during the Medicare coverage gap phase was associated with higher risk of DOAC discontinuation, which in turn was associated with increased risk of subsequent stroke and SE events among beneficiaries with NVAF. Despite policy reforms aimed at closing the coverage gap, beneficiaries continue to shoulder considerable cost-sharing burden for Part D drugs. These findings suggest that further shifts in OOP drug costs to beneficiaries could have long-term negative clinical implications for patients, especially for acute and often irreparable health events like stroke, and underscore the need to consider the unintended impact of decisions based on the short-term financial savings on long-term clinical and economic consequences for patients and health systems.

References

Ballestri S, Romagnoli E, Arioli D, et al. Risk and management of bleeding complications with direct oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolism: a narrative review. Adv Ther. 2023;40(1):41–66.

Yamashiro K, Kurita N, Tanaka R, et al. Adequate adherence to direct oral anticoagulant is associated with reduced ischemic stroke severity in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28(6):1773–80.

Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955–62.

Ozaki AF, Choi AS, Le QT, et al. Real-world adherence and persistence to direct oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13(3): e005969.

Chen N, Brooks MM, Hernandez I. Latent classes of adherence to oral anticoagulation therapy among patients with a new diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2): e1921357.

Hernandez I, He M, Brooks MM, Saba S, Gellad WF. Adherence to anticoagulation and risk of stroke among Medicare beneficiaries newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2020;20(2):199–207.

Hernandez I, He M, Chen N, Brooks MM, Saba S, Gellad WF. Trajectories of oral anticoagulation adherence among Medicare beneficiaries newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(12): e011427.

Services CfMM. Costs in the Coverage Gap; 2021. https://www.medicare.gov/drug-coverage-part-d/costs-for-medicare-drug-coverage/costs-in-the-coverage-gap. Accessed March 10, 2021.

Cubanski J, Damico A, Neuman T. Medicare Part D in 2018: the latest on enrollment, premiums, and cost sharing. May 17, 2018. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-part-d-in-2018-the-latest-on-enrollment-premiums-and-cost-sharing/. Accessed March 10, 2021.

Park YJ, Martin EG. Medicare part D’s effects on drug utilization and out-of-pocket costs: a systematic review. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(5):1685–728.

Polinski JM, Kilabuk E, Schneeweiss S, Brennan T, Shrank WH. Changes in drug use and out-of-pocket costs associated with Medicare Part D implementation: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(9):1764–79.

CMS Eligibility for Low-Income Subsidy, Low Income Subsidy Guidance for States; 2009. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Eligibility-and-Enrollment/LowIncSubMedicarePresCov/EligibilityforLowIncomeSubsidy.

Ganapathy V, Xie L, Wang Y, Zhang Q, Baser O. Prescription fill patterns after reaching the Medicare Part D coverage gap among patients with COPD on maintenance bronchodilators. Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Annual Meeting; 2017.

Polinski JM, Shrank WH, Huskamp HA, Glynn RJ, Liberman JN, Schneeweiss S. Changes in drug utilization during a gap in insurance coverage: an examination of the Medicare Part D coverage gap. PLoS Med. 2011;8(8): e1001075.

Research Data Assistance Center: Find, Request and Use CMS Data; 2022. https://resdac.org/. Accessed Oct 7, 2022.

Melgaard L, Gorst-Rasmussen A, Lane DA, Rasmussen LH, Larsen TB, Lip GY. Assessment of the CHA2DS2-VASc score in predicting ischemic stroke, thromboembolism, and death in patients with heart failure with and without atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1030–8.

Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJ, Lip GY. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest. 2010;138(5):1093–100.

Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–82.

Imbens GW. The role of the propensity score in estimating dose-response functions. Biometrika. 2000;87(3):706–10.

Brookhart MA, Wyss R, Layton JB, Sturmer T. Propensity score methods for confounding control in nonexperimental research. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(5):604–11.

Zissimopoulos J, Joyce GF, Scarpati LM, Goldman DP. Did Medicare Part D reduce disparities? Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(2):119–28.

Chandra A, Flack E, Obermeyer Z. The health costs of cost-sharing. HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series RWP21-005, March 2021; 2021.

Zhou B, Seabury S, Goldman D, Joyce G. Formulary restrictions and stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Manag Care. 2022;28(10):521–8.

Deitelzweig S, Luo X, Gupta K, et al. All-cause, stroke/systemic embolism-, and major bleeding-related health-care costs among elderly patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation treated with oral anticoagulants. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2018;24(4):602–11.

Amin A, Keshishian A, Trocio J, et al. A real-world observational study of hospitalization and health care costs among nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients prescribed oral anticoagulants in the U.S. Medicare population. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(5):639–51.

Newman TV, Gabriel N, Liang Q, et al. Comparison of oral anticoagulation use and adherence among Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in stand-alone prescription drug plans vs Medicare Advantage prescription drug plans. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2022;28(2):266–74.

Wong ES, Done N, Zhao M, Woolley AB, Prentice JC, Mull HJ. Comparing total medical expenditure between patients receiving direct oral anticoagulants vs warfarin for the treatment of atrial fibrillation: evidence from VA-Medicare dual enrollees. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27(8):1056–66.

Cubanski J, Neuman T, Damico A. Closing the Medicare Part D coverage gap: trends, recent changes, and what’s ahead; 2018. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/closing-the-medicare-part-d-coverage-gap-trends-recent-changes-and-whats-ahead/. Accessed Oct 28, 2022.

Cubanski J, Neuman T, Freed M. Explaining the prescription drug provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act; 2022. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/explaining-the-prescription-drug-provisions-in-the-inflation-reduction-act/. Accessed Oct 24, 2022.

Acknowledgements

Author Contributions

Tabassum Salam, Urvi Desai, Patrick Lefebvre, Jian-Yu E, François Laliberté, Brahim Bookhart, and Akshay Kharat contributed to the study design. Formal analyses were conducted by Alexandra Greatsinger and Nina Zacharia. All authors contributed to the critical interpretation of data as well as drafting/editing the manuscript, have approved the final version of this manuscript, and take responsibility for the integrity of this research study.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Funding

This study and corresponding Rapid Service and Open Access fees were funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. The sponsor was involved in the study design, data analysis, manuscript preparation, and publication decisions.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

The authors thank Serena Kongara, who is an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., for the support in conducting the statistical analyses.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, as they are subject to a data use agreement between Analysis Group, Inc., and the data provider. The data are available through requests made directly to CMS.

Ethical Approval

The data were de-identified and complied with HIPAA and the Declaration of Helsinki; therefore, an IRB exemption was obtained per Title 45 of CFR, Part 46.101(b)(4) (18) from WCG IRB.

Conflict of Interest

Urvi Desai, Patrick Lefebvre, François Laliberté and Alexandra Greatsinger are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a company that received consultancy fees from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC for this study. Jian-Yu E and Nina Zacharia were employees of Analysis Group at the time this study was conducted. Brahim Bookhart and Akshay Kharat are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and are stockholders of Johnson & Johnson.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salam, T., Desai, U., Lefebvre, P. et al. Unintended Consequences of Increased Out-of-Pocket Costs During Medicare Coverage Gap on Anticoagulant Discontinuation and Stroke. Adv Ther 40, 4523–4544 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-023-02620-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-023-02620-z