Abstract

Introduction

Current guidelines for the management of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) recommend regular multi-parametric assessment of a patient’s risk of clinical worsening or death, with the goal of achieving/maintaining a low-risk status. This international survey investigated how physicians currently assess risk and compared their clinical gestalt (judgement of risk) with the risk calculated using an algorithm based on the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) pulmonary hypertension guidelines and demonstrated to provide accurate mortality estimates.

Methods

PAH-treating physicians from Europe and the United States were surveyed on (1) how frequently they evaluated the recommended risk-assessment parameters and (2) to complete patient record forms (PRFs) with details on 5–7 recent adult PAH patients receiving treatment. For each PRF, physicians provided (1) their gestalt judgement of current risk and (2) details of the risk-assessment parameters measured. In accordance with the published method, measurements for ≥ 2 (of 6 selected) variables were required to calculate risk. Each variable was assigned a score of 1, 2 or 3 according to whether the measurement was within the thresholds for the low-, intermediate- or high-risk categories, as defined in the ESC/ERS guidelines. The average score represented the patient’s calculated risk.

Results

In total, 90 physicians (52 cardiologists, 38 pulmonologists) completed the survey, providing a total of 623 PRFs; of these, 365 (59%) included ≥ 2 measurements required to calculate risk. Among these patients, the percentages assigned to low-, intermediate- and high-risk categories based on gestalt/calculation were 32%/15%, 45%/68% and 22%/17%, respectively. Overall, there was concordance between the gestalt and calculated risk category for 45% of patients. The greatest level of disparity was for patients judged to be at low risk, where 80% were assigned to higher risk categories based on their calculated risk.

Conclusions

The results of this survey demonstrate that multi-parametric risk assessment is being performed in clinical practice, but not always to the extent recommended in the current guidelines. Further study on the utility of more regular measurement is required.

Funding

Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a progressive, severely debilitating and incurable disease characterised by increased pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary arterial pressure, which ultimately leads to right heart failure and death. Although survival has improved in the modern management era [1,2,3] compared with historical data [4], the prognosis remains poor [5]. Therefore, assessment of a patient’s risk of disease progression and mortality has become an essential part of PAH management and is now centred around risk-based treatment algorithms [6,7,8,9].

Based on a growing body of evidence, the current guidance [8, 9] from leading experts recommends regular multi-parametric risk assessment whereby patients are classified as being at low (< 5%), intermediate (5–10%) or high (> 10%) risk of 1-year mortality [6,7,8,9]. It is recommended that a comprehensive assessment should be conducted at baseline (i.e. diagnosis/treatment initiation); in the event of clinical worsening, at least every 6–12 months routinely; and 3–6 months after a change in therapy [7,8,9]. To aid risk classification, the 2015 European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) pulmonary hypertension (PH) guidelines outline 9 determinants of prognosis, comprising 13 variables and their corresponding low-, intermediate- and high-risk thresholds. These variables include clinical and functional assessments, biochemical markers, and imaging and haemodynamic parameters [9]. The patient’s overall risk at a given timepoint is a composite measure of the individual variables, which may not all fall into the same risk category. It is the patients’ overall risk that is to be used to drive decisions on whether and how to escalate treatment, with the goal of achieving/maintaining a low-risk status [6,7,8,9].

Translating all available measures and indicators of patient risk into a single risk category can pose a significant challenge for the treating physician and, as a result, research has focused on development of standardised tools and protocols for risk stratification. Several groups have retrospectively analysed data from prospective PAH registries to develop scoring systems that can aid risk assessment in clinical practice. For example, the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term PAH Disease management (REVEAL) has been used to develop a calculator in which measurements for 12–14 variables are entered and their prognostic values weighted in order to derive a final risk score [10, 11]. Other studies have also taken a systematic approach to accurately predict risk of mortality, with the aim of developing a tool/scoring system that could be easily implemented in clinical practice without placing too much burden on the patient. These include analyses performed using data from the Swedish PAH Registry [12] and the Comparative, Prospective Registry of Newly Initiated Therapies for Pulmonary Hypertension (COMPERA) study [13], which assigned risk to patients newly diagnosed with PAH using a scoring system whereby an overall risk score was obtained by averaging scores based on at least two measurements across 6–8 of the 13 variables outlined in the ESC/ERS guidelines. Each of these risk assessment strategies were able to accurately stratify patients according to their 1-year mortality estimates [10,11,12,13]. In another study, data from the French PH Registry were used to calculate patients’ risk according to the number of low-risk criteria present from a total of 3, 4 or 5 variables, and found that a greater number of low-risk criteria was indicative of better survival [14]. While the approaches taken in each of the studies described above differed, all point to the same conclusions: that regular risk assessment can and should be performed.

While there is now a clear mandate for risk assessment in the management of PAH, how this is implemented in clinical practice remains unclear. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first international study conducted to investigate how physicians currently assess risk of clinical worsening or death in patients with PAH, and how closely they adhere to the recommendations on risk assessment in the 2015 ESC/ERS guidelines. The aim of this study was to investigate how physicians assess PAH patient risk in clinical practice and to explore differences and similarities between the risk category assigned to patients by the treating physician (gestalt judgement of risk) and the risk category calculated using a published algorithm for risk assessment (calculated risk) [13].

Methods

Participants

The study included respondents from France, Germany, Italy and the United States (US). Data were collected between October 9 and November 6, 2017. Respondents were cardiologists and pulmonologists who had worked in their specialty for between 2 and 30 years, and who managed at least 7 patients with PAH at the time of the survey. Full eligibility criteria for survey respondents are described in Supplemental Table 1. Respondents were predominantly recruited via panel databases (membership of which was reliant on relevant privacy permission) maintained by GLocalMind Inc. (Texas, US). Respondents were remunerated for their participation (equivalent range US$60–80 per respondent, in accordance with fair market value rates).

Development of Questionnaire

The questionnaire (Supplementary appendix) was developed by Cello Health Insight (London, UK) in collaboration with Actelion Pharmaceuticals (Allschwil, Switzerland) and was conducted by Cello Health Insight. The questionnaire was developed in English, with French, German and Italian translations prepared by GlobaLexicon (London, UK). The accuracy of the translations was confirmed by Cello Health Insight’s language team in partnership with Actelion Pharmaceuticals. A pilot survey was conducted in the US with 6 of the 90 respondents in total to confirm that data could be collected accurately with no programming errors and that the questions were understood by the respondents with no ambiguity.

Execution of Questionnaire

The questionnaire was completed by respondents online. Respondents first had to answer some initial screening questions, to determine if they met the study’s eligibility criteria (Supplementary Table 1). Eligible respondents were then asked to complete 3 tasks, relating to the 9 parameters defined as “determinants of prognosis” in the 2015 ESC/ERS guidelines (Table 1) [9]. Respondents with missing or invalid entries were removed from the final analysis set.

The first task consisted of several general questions to determine (1) which parameters respondents used to assess their PAH patients when evaluating prognosis, severity, clinical worsening and/or response to therapy (hereafter referred to as risk), (2) the timepoint(s) at which they performed the assessments, and (3) how often they performed the assessments. Note, no minimum number of variables were required to be reported by physicians for data to be included in this survey; however, at least 2 variables were required for the subsequent risk calculation.

The second task was a maximum-difference scaling survey used to rank the 9 parameters in terms of their importance to respondents for assessing risk, on a common scale. There were 9 evaluation rounds in the survey. Each round contained a different choice set of 4 of the 9 parameters, with each parameter being presented 4 times in total. From each choice set, respondents were asked to select the most and least important parameter in their practice for risk assessment in patients with PAH. The maximum difference means were calculated from the difference between the number of times each parameter was chosen as the most or the least important (the ‘count’), and ranking parameters based on these differences. Important parameters were defined as those that score between 1 and 49% higher than the average for all parameters.

In a third task, all respondents were asked to provide details of the 5–7 most recent adult patients with PAH they had managed in patient record forms (PRFs). Patients were included if they were currently receiving an endothelin receptor antagonist as mono- or combination therapy and were not taking part in a clinical trial. Quality checks were performed to ensure that all reported variables had a corresponding and appropriate value entered. Respondents were asked “In your opinion, how would you describe the patient’s current level of risk in terms of clinical worsening or death”, hereafter referred to as gestalt judgement.

Calculation of Risk

In the PRFs, respondents were asked to provide each patient’s measurements, where available, from the last clinic visit for the 13 variables (across the 9 parameters/determinants) specified in the ESC/ERS guidelines (Table 1). ‘Calculated risk’ refers to patient risk, as calculated using the strategy published by Hoeper et al. [13], which provided accurate 1-year mortality estimates for patients with PAH. Risk scores were calculated from all PRFs that included measurements for ≥ 2 of the following variables at the most-recent clinic visit: New York Heart Association/World Health Organization functional class (WHO FC), 6-min walk distance (6MWD), brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-proBNP) plasma levels, right atrial pressure (RAP), cardiac index (CI) and mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2). All variables were assigned a score of 1, 2 or 3 according to whether the measurement was within the ESC/ERS guideline thresholds for the low-, intermediate- or high-risk categories, respectively. The average score (rounded to the nearest integer) was calculated and this represented the patient’s calculated risk category, i.e. average scores of ≥ 1 to < 1.5 were considered low risk, average scores of ≥ 1.5 to < 2 were considered intermediate risk and ≥ 2 to 3 were considered high risk [13].

Statistical Analysis

For the maximum-difference scaling, R language was used to process the raw data and a pre-compiled STAN Hierarchical Bayes model was used to determine the importance value, with a mean importance value of 100. To ensure the stability and consistency of the results, the analyses were run several times with varied parameters. No other formal statistical comparisons were made, and all data are presented descriptively.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Cello Health Insight is a member of the British Healthcare Business Intelligence Association and the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association, and this research was conducted in accordance with their guidelines on market research. All methods performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Results

Characteristics of Physicians and Patients

In total, 94 physicians, including 54 (57%) cardiologists and 40 (43%) pulmonologists completed the survey. Four physicians (two cardiologists and two pulmonologists) were removed from the analysis due to missing or invalid information. The distribution of physicians by country, specialty, work setting, years qualified in their speciality and the number of PAH patients under their care is provided in Supplemental Table 2.

In total, physicians provided 623 PRFs and valid measurements were entered for all variables reported. Over half (56%) of patients were female, average age was 56.4 years, all patients had a time-from-PAH diagnosis until survey start of ≥ 13 months (65% ranged from 13 to 48 months), and PAH aetiology was idiopathic in 54% of cases (Table 2).

Identification of the Parameters Measured by Respondents to Assess Risk

Table 1 shows the 9 parameters, comprising 13 variables, set out in the 2015 ESC/ERS guidelines that respondents were asked to consider during the questionnaire. Regarding the relative importance of these parameters with respect to assessing risk of clinical worsening or death in patients with PAH, progression of symptoms was considered by respondents to be the most important (score > 150; ‘very important’), followed by haemodynamics, WHO FC, clinical signs of right heart failure and 6MWD (scores between 100 and 150; ‘important’) (Supplemental Fig. 1).

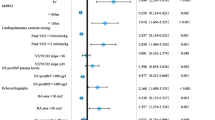

Figure 1 shows the frequency at which physicians recall measuring each of the 9 parameters, together with the percentage of PRFs that included a measurement for that parameter at the last patient visit. None of the 9 parameters were assessed by all physicians; according to physicians, the parameter most often measured was progression of symptoms (91%), and the least often measured was cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET; 54%). To determine the stage(s) at which these parameters are measured, physicians were asked which assessments they perform at diagnosis/treatment initiation (hereafter referred to as ‘baseline’), follow-up, after a change in therapy, and/or in case of clinical worsening. For all parameters, physicians reported that they performed the assessments at baseline more often than at any follow-up visit. For parameters that can be assessed during a routine consultation with patients (e.g. symptom progression, WHO FC, clinical signs of right heart failure and syncope), the percentage of physicians reporting assessment remained relatively stable across baseline and follow-up visits (less than 20 percentage points lower at follow-up vs. baseline). In contrast, for parameters that cannot be routinely assessed in a consultation room without additional time/resource/equipment, such as CPET, the percentage of physicians reportedly measuring these parameters at follow-up visits was up to 49 percentage points lower than at baseline.

Frequency of testing as reported by physicians (n = 90) and as evidenced by measurements included in patient record forms (n = 623). †All respondents (n = 90) were first asked “which [of the nine] parameters do you consider in order to assess your adult PAH patients, e.g. when assessing prognosis, severity, clinical worsening and/or assessing a patients response to therapy?” and to select all that apply. For each parameter they selected, respondents were then asked “For each parameter, when do you perform the assessment” and to select “at baseline/treatment initiation”, “at follow-up appointment”, “after change in therapy”, and/or “in case of clinical worsening” and to select all that apply. ‡For parameters that are comprised of more than one variable, a measurement for any one of its component variables was considered a count, i.e. PRFs with a cardiac index measurement were considered to have a measurement for the parameter ‘haemodynamics’. 6MWD 6-min walk distance; CPET cardiopulmonary exercise testing; NT-proBNP N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide; PRF patient record form; RHF right heart failure; WHO-FC World Health Organization functional class

The percentage of measurements included in the PRFs was broadly in alignment with the physicians’ recollection of how often they assess each parameter, albeit slightly lower overall (Fig. 1). For parameters (e.g. haemodynamics) that comprise more than 1 variable (e.g. RAP, CI, SVO2), a measurement for any single variable was considered a count, i.e., PRFs with a CI measurement were considered to have a measurement for the parameter ‘haemodynamics’. When considering all 13 possible variables in the guidelines, 83/623 (13%) PRFs included ≤ 2 measurements, 374/623 (60%) included 3–6 measurements and 166/623 (27%) included ≥ 7 measurements.

Of the 6 variables of interest for the risk calculation, ≥ 2 variables were available for 365 (59%) patients, ≥ 3 in 190 (30%) patients, ≥ 4 in 76 (12%) patients, ≥ 5 in 57 (9%) patients, and all 6 variables were available in 39 (6%) patients. As ≥ 2 variables were required for risk calculation, only 365 (59%) of the physician-provided PRFs were included in this analysis.

Physicians’ Gestalt Judgement of Risk

Of the 623 patients for whom physicians provided information, the physicians classified 204 (33%), 296 (48%) and 123 (20%) to be at low, intermediate and high risk, respectively (Fig. 2). Results were similar for the subset of patients (n = 365) for whom a risk score could be calculated (Fig. 2).

Gestalt and calculated risk. Gestalt risk: respondents were asked “in your opinion, how would you describe the patient’s current level of risk in terms of clinical worsening or death?” and to select either low, intermediate or high risk. Calculated risk: The 6 variables used to calculate risk of 1-year mortality are outlined in Table 1 and are: WHO FC, 6MWD, BNP/NT-proBNP, RAP, cardiac index, SvO2

Risk Calculation Analysis

Of the 365 PRFs included in the risk calculation analysis, 54 (15%), 249 (68%), and 62 (17%) were calculated to be in the low-, intermediate- and high-risk categories, respectively (Fig. 2).

Comparison of Physicians’ Gestalt Judgement of Risk with Calculated Risk

The concordance between physicians’ gestalt judgement of patients’ risk and calculated risk is shown by gestalt risk category in Fig. 3. Overall, the gestalt and calculated risk categorisations aligned for 45% of patients, with the greatest agreement observed in the largest group, i.e. those judged as intermediate risk. For patients judged to be at low risk (n = 118), 94 (80%) were calculated as being at higher risk. There was also poor concordance between gestalt and calculated risk categories for patients judged to be at high risk (n = 81), with 69% of patients calculated as being at lower risk. The overall concordance between gestalt and calculated risk scores was similar for EU and US physicians (40.3% vs. 39.3%, respectively) and for pulmonologists and cardiologists (43.0% and 38.7%) (Supplementary Fig. 2).

For patients judged to be at low risk, the concordance with the risk categories for the individual variable measurements, as defined by the thresholds set out in the ESC/ERS guidelines, is shown in Fig. 4. The variables with the greatest percentage of discordance (i.e., cases in which the risk category of the individual measurement would be classed as intermediate or high according to the guidelines) were RAP (n = 22), 6 MWD (n = 102), and NT-proBNP levels (n = 61), with 82%, 52% and 51% of measurements, respectively, being within the bounds of either intermediate- or high-risk categories. Moreover, 9% of 6MWD measurements (n = 9) and 41% of RAP measurements (n = 9) were within the bounds of the high-risk category. Supplementary Fig. 3 shows the same for patients judged to be intermediate (A) and high (B) risk.

Discussion

In recent years, the assessment of clinical worsening or death in patients with PAH has become increasingly important for informing treatment decisions, with experts now recommending physicians perform multi-parametric risk assessment regularly at routine appointments [6,7,8,9]. To our knowledge, this is the first international survey of physicians to investigate how risk assessment is currently being implemented in clinical practice and the results show that there are differences between physicians’ gestalt judgement of patient risk and patient risk as calculated using an objective algorithm. It is important to note that 41% of the patients were excluded from the risk calculation analysis due to insufficient measurements, indicating that risk assessment as recommend in the ESC/ERS guidelines may often not be performed.

This study captured which parameters physicians measure and how often they do so, based on both physicians’ recollection of their usual practice and on which measurements were present in the PRFs. These 2 sets of information were broadly aligned and demonstrate that most physicians evaluate progression of symptoms, clinical signs of right heart failure and WHO FC, with NT-proBNP levels, CPET and haemodynamics being less frequently assessed. Overall, haemodynamics and CPET were the parameters least likely to be measured at follow-up, which is not in contravention of the guidelines, as they suggest assessment of these every 6–12 months [8, 9], nor is it unexpected, given that many centres do not have access to CPET and many do not perform right heart catheterisation routinely to avoid potentially unnecessary invasive procedures [15]. However, it does seem to disagree with the results from the maximum-difference scaling survey, which demonstrated that physicians consider haemodynamics as the second-most important parameter for assessing prognosis. This apparent misalignment may be partly explained by the finding that physicians stated that they measure these 2 parameters more often at baseline than at follow-up visits. Given the inclusion criterion that patients must currently be receiving an endothelin receptor antagonist and that, for all patients with a value reported, the time from diagnosis was at least 13 months, the most recent clinic visit for these patients was likely to have been a follow-up visit. In addition, the exact timing of the last visit was not captured in this survey, so another possible reason for misalignment may be that it did not fall within the timeframe suggested for these assessments.

Our study demonstrates a discordance between physicians’ gestalt judgement of risk and calculated risk. For example, of the patients judged to be at low risk (n = 118), 80% were calculated to be at higher risk and of the patients judged to be at high risk (n = 81), 69% were calculated to be at lower risk. The reasons for this lack of agreement are not clear, but could be due to several factors. First, physicians may not be measuring enough parameters to produce an accurate algorithm-based estimate of risk. In the Hoeper analysis, 95.3% of patients had at least 4 variables measured and 55.4% had all 6 [13], compared with 12.2% and 6.3% in this study, respectively. In addition, it is possible that physicians may not agree with, or strictly apply, the parameter thresholds given in the guidelines. Finally, a physician’s clinical gestalt is based on more than just the assessments used in the algorithm to calculate risk, such as the patient’s disease aetiology, age, gender and comorbidities, as well as the physicians’ overall feeling of how the patient is doing as compared to previous consultations. Importantly, as this study did not capture outcome data, we do not know how well the physicians’ gestalt judgement of risk would stratify patients according to their 1-year risk of mortality and how that compares to the methods implemented by Hoeper et al. [13]. The potential for under- and over-estimation of risk should be further explored, as this can have profound detrimental impacts on patients’ lives, such as increasing the likelihood of clinical worsening and death in patients at intermediate or high risk, and potentially subjecting low-risk patients to unnecessary treatments and/or assessments, further impacting their quality of life.

Limitations of this study include selection bias and recall bias, which are inherent to all surveys, and that the results may be different from those that would be obtained in countries not studied. The main limitation of this study is the lack of clinical outcome data, which prevents evaluation of the effectiveness of gestalt judgement in stratifying patients according to their 1-year risk of mortality. Furthermore, more qualitative data would be required to better understand why physicians choose to assess certain variables and not others, and what potential barriers they face, in order to reconcile the observed differences between perceived and calculated risk. Finally, it would be interesting to compare how physicians’ gestalt compares to risk scores derived using other methods, such as the approach published by Boucly et al. [14]. However, the French approach stratifies patients according to the number of variables defined as low risk in the ESC/ERS guidelines and does not directly categorize patients as ‘low’, ‘medium’ or ‘high’ risk. Given this, a comparison could not be performed here.

Conclusions

Overall, the results of this survey demonstrate that multi-parametric risk assessment is being performed in clinical practice, but not always to the extent recommended in the 2015 ESC/ERS guidelines [8, 9]. Further study would be required to establish how well physicians’ gestalt estimates a patient’s risk of disease progression and to determine whether more regular assessment of objective measures could improve the accuracy of patient risk stratification.

References

Farber HW, Miller DP, Poms AD, et al. Five-year outcomes of patients enrolled in the REVEAL Registry. Chest. 2015;148(4):1043–54.

Pulido T, Channick RN, Delcroix M, et al. Long-term survival and safety with macitentan in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: results from the SERAPHIN Study and its open-label extension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:A2294.

Galiè N, Gaine S, Channick R, et al. Long-term survival and safety with selexipag in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: results from the GRIPHON study and its open-label extension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:631–2.

D’Alonzo GE, Barst RJ, Ayres SM, et al. Survival in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Results from a national prospective registry. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(5):343–9.

Thenappan T, Ormiston ML, Ryan JJ, Archer SL. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: pathogenesis and clinical management. BMJ. 2018;360:j5492.

Galiè N, McLaughlin VV, Rubin LJ, Simonneau G. An overview of the 6th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(1):1802148.

Galiè N, Channick RN, Frantz RP, et al. Risk stratification and medical therapy of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(1):1801889.

Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Respir J. 2015;46(4):903–75.

Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(1):67–119.

Benza RL, Gomberg-Maitland M, Miller DP, et al. The REVEAL registry risk score calculator in patients newly diagnosed with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2012;141(2):354–62.

Benza RL, Gomberg-Maitland M, Elliott CG, et al. Predicting Survival in Patients with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: The REVEAL Risk Score Calculator 2.0 and Comparison with ESC/ERS-Based Risk Assessment Strategies. Chest. 2019;S0012-3692(19):30152–7.

Kylhammar D, Kjellstrom B, Hjalmarsson C, et al. A comprehensive risk stratification at early follow-up determines prognosis in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(47):4175–81.

Hoeper MM, Kramer T, Pan Z, et al. Mortality in pulmonary arterial hypertension: prediction by the 2015 European pulmonary hypertension guidelines risk stratification model. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(2):1700740.

Boucly A, Weatherald J, Savale L, et al. Risk assessment, prognosis and guideline implementation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(2):1700889.

Rosenkranz S, Preston IR. Right heart catheterisation: best practice and pitfalls in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir Rev. 2015;24(138):642–52.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants of this study for completing the survey, and Jordan Mullen for his support in designing and conducting the survey and collecting data.

Funding

Sponsorship for this study was funded by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd. The rapid service fee and Open Access fees were funded by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship of this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing Assistance

Medical writing and submission support were provided by Victoria Atess, PhD, and Richard McDonald (Watermeadow Medical, an Ashfield Company), funded by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd.

Disclosures

Jonathan E. Simons is an employee of Cello Health Insight, which was commissioned by Actelion Pharmaceuticals, Ltd. to conduct this study on their behalf. Elena B. Mann is an employee of Cello Health Insight, which was commissioned by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd to conduct this study on their behalf. Adam Pierozynski is an employee of Cello Health Insight, which was commissioned by Actelion Pharmaceuticals, Ltd. to conduct this study on their behalf.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Cello Health Insight is a member of the British Healthcare Business Intelligence Association and the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association, and this research was conducted in accordance with their guidelines on market research. All methods performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8427647.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Simons, J.E., Mann, E.B. & Pierozynski, A. Assessment of Risk of Disease Progression in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: Insights from an International Survey of Clinical Practice. Adv Ther 36, 2351–2363 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01030-4

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01030-4