Abstract

The purpose of this study is to assess different factors under the Bangladesh labour legislation for promoting work-satisfaction of the global garment workers in Bangladesh. A convenient sampling technique was used for collecting 208 employee responses through a five-point Likert scale structured questionnaire. The respondents were garments-manufacturing industry workers working in three hot spots known as towns of Savar and Ashulia (Dhaka District) and Gazipur Sadar (Gazipur District). The survey was conducted between November and December, 2019. This research study finds that seven factors significantly influence work-satisfaction of garment workers in Bangladesh. Among these, four are related to the non-pecuniary factors: supervisory treatment of the workers, working environment, hygienic canteen facility, and medical facility. The three other factors, namely, the amount of salary, timely payment of salary and increment policy for the workers, play a significant part in workers’ satisfaction. This study helps in assessing the opinions of the workers about their work-satisfaction as well as policy planning for the development of the garments-manufacturing industry. Also, this study will add value to the setting of South Asian developing countries and industries because of the similar socio-economic environment to Bangladesh.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

With regard to work-satisfaction, Hinkin and Schriesheim (1994) find a positive relationship between the reward scheme of supervision and worker satisfaction and performance. Taylor (2008) demonstrates that the existence of a provident fund and supportive financial benefits along with fair payments of the same bring workers’ satisfaction. Guest (2002) examines the work-satisfaction from the perspective of human resource management and shows that the work-satisfaction is associated with equal opportunities, family-friendly, and anti-harassment practices. It is recommended that worker-friendly human resource management be applied in the context of a partnership or mutual-gain framework.

In the context of a developing Asian economy, Dharmasri and Vathsala (2012) investigate the work-satisfaction in the apparel-manufacturing industry in Sri Lanka. They find that ‘perceived organisational support’ moderates the relationship between ‘participation in decision making’ and effective commitment, and ‘participation in decision making and work-satisfaction’. In his recent study, Arslan (2020) aggregates three dimensions of financial, physiological, and psychological exploitations that cause labour dissatisfaction in the garments industry of Pakistan. In the context of the Indian experience, Thomas et al. (2010) explore the link between cultural behavioural traits, the potential effect of industrialisation, and multiple domains of the work-satisfaction. Their study demonstrates a statistically significant impact of both extrinsic and intrinsic moderating factors on Indian employees' work-satisfaction. Hechanova and Manaois (2020) find that satisfaction relies on ethical leadership that affects organisational norms and controls, and employees’ attitudes in the Philippines. In Malaysia, reward, referent, and expert powers are positively related to worker satisfaction with supervision. Moreover, both coercion and power influence satisfaction with supervision negatively (Junaimah et al. 2015). High-performance work systems are found significantly and positively correlated with the work-satisfaction in China (Ming et al. 2014).

In the setting of garments global supply chain industry in Bangladesh, workers are striking imbalance family life; thus, the study suggests ensuring friends and family-related benefits like day-care facilities for female workers with children, transportation facility, and subsidised meal options at the staff canteen for employees (Syed 2015). Asma et al. (2017) examine the work-satisfaction of working mothers in the garments industry in Bangladesh. The study shows that organisational factors such as work conditions, wages, job security, and stress significantly influence mother employees’ work-satisfaction in this industry. Another study by Shabnam and Sarker (2012) finds that workers' level of satisfaction mainly relies on their amount of salary. Along the same lines, Zohir (2007) adds that workers' quality of life depends on festival bonuses,Footnote 1 attendance bonuses, and wage increments. Furthermore, Khatun and Moazzem (2007) take into account fair payment policies for the workers' satisfaction. They recommend several factors for deciding the minimum wage for industrial workers. For example, the minimum wage should be a living wage for the workers, an introduction of a unique wage structure for similar types of industry and adjustment of salary in relation to the economic development of the country.

Although some research studies based on various nations demonstrate an inverse relationship between workers' wages and labour productivity (Kohpaiboon 2003; Hermawan and MSi 2011); those analyses disregard the nicety of neoclassical theory. The neoclassical theory makes it clear that a standard minimum wage regulation and an effective implementation procedure may boost labour productivity and benefit society as a whole (Gaffar Khan et al. 2019). Further, Sadovský and Matějková (2019) demonstrate that raising the minimum wage is not correlated with economic development. They believe that eliminating the guaranteed wage is a practical response to the situation and the demands of the economy. However, the authors’ approach may not be applicable in Bangladesh, at least for the following two reasons. Firstly, their study is based on European countries, and their socioeconomic and political structure is not the same compared to the South Asian developing countries like Bangladesh. Secondly, their study ignores the monopsony theory of minimum wage by Hirsch and Schumacher (1995). This theory is applicable when a single sector has market power through its production, and the Bangladesh garments-manufacturing industry is one such example. Contrary to the monopsony theory, Zdeněk Sadovský and Jitka Matějková’s study is not based on a single sector; instead, they take into account the whole sectors in a combined fashion of a country, which is contrary to the present approach of this study.

In respect of wage and living standards, Syed et al. (2014) note that the garment workers in Bangladesh lag far behind the conditions of workers in other countries such as China, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam. As a result, this industry is less efficient compared to the neighbouring competitive countries. For instance, the Bangladesh garments-manufacturing industry earns US$ 21.5 billion with an active workforce of four million in the fiscal year 2012–2013 while Vietnam earns US$ 17 billion with only 1.3 million workers in the same period.

Though the garments global supply chain industry in Bangladesh has been playing a vital role in alleviating poverty, reducing unemployment and earning foreign currency, this industry is plagued by labour dissatisfaction. There are many studies covering human resource management, social, economic, and political areas of the garments industry; nonetheless, a few are in regard to labour satisfaction with the labour law. Through a systematic literature review, it is found that the previous studies are not comprehensive in terms of study areas, methods, and subject matters. Thus, this research study is indispensable to filling up the serious gap.

The labour frustration occurs although Bangladesh enacts new labour legislation known as Bangladesh Labour Act, 2006 to ensure workers’ satisfaction in all aspects. As the labour legislation commitment is to ensure legitimate rights and privileges for the garment workers, this study aims to find the factors under the labour legislation, which influence work satisfaction in the garments global supply chain industry. There are two objectives of this study:

-

I.

To analyse the provisions adopted under the national labour legislation; and

-

II.

To find the labour provisions under the national labour legislation, which influence the work satisfaction of the global garments supply chain workers in Bangladesh.

Within this context, the paper addresses the following research question:

-

What factors under Bangladesh labour legislation influence the worksatisfaction of global garment workers in Bangladesh?

This study assesses, evaluates, and analyses labour satisfaction under labour legislation in Bangladesh.

2 Factors’ influence under labour law

Bangladesh labour law is also known in Bangla as Bangladesh Shromo Ain, 2006 (from now on Bangladesh Labour Act, 2006 or BLA, 2006, or national labour law), and it has been amended in 2009, 2010, 2013, and 2018 to ensure workers' satisfaction in all aspects.

In response to the research question, 12 independent variables have been selected purposively from the national labour legislation with an intention to know the factors under the current labour law, which influence the garments-manufacturing workers in Bangladesh. All the independent variables are divided into two broad categories of monetary and non-monetary factors.

2.1 Monetary data

Monetary factors include the earnings of the workers. In the setting of a developing country like Bangladesh, monetary values are indispensable for workers (Sarker and Afroze 2014). Thus, profit-sharing to the workers, amount of salary, timely pay salary, timely pay bonus, increment policy, and compensation for the accident may be categorised as the workers' monetary factors.

Chapter XV of the Bangladesh labour legislation has provisions in regard to workers’ participation in company profits. The legislation has a specific provision that requires the establishment of a workers’ participation fund and a workers’ welfare fund in conformance with this Chapter (s. 234 (a) BLA 2006). The company will have to pay 5% of the previous year's net profit to be distributed in the proportion of 80:10:10 to the participatory fund, welfare fund, and workers’ welfare foundation fund (s. 234 (b) BLA 2006).

Bangladesh has no separate minimum wage legislation (Syed 2018). However, under Chapter XI of the labour legislation, the government established Minimum Wages Board [(hereinafter MWB) (s. 138 BLA 2006)]. The MWB determines minimum wage rates based on a variety of factors such as cost of living, standard of living, cost of production, productivity, product price, inflation, nature of work, risk, business capability, and socioeconomic conditions of the country (s. 141 BLA 2006). Most of the provisions regarding minimum wage are in line with the Minimum Wage-Fixing Convention (1970, No. 131); Minimum Wage-Fixing Machinery Convention, (1928, No. 26); Minimum Wage-Fixing Recommendation (1970, No. 135); and Minimum Wage-Fixing Machinery Recommendation (1928, No. 30) of International Labour Organisation (ILO 1919).

For overtime work, a worker is entitled to having twice of his ordinary rate of basic wage and dearness allowance, as well as ad-hoc or interim wage, if any, according to current labour legislation (s. 108 BLA 2006). Furthermore, time of payment of wages (s. 123 BLA 2006), liability of the employer to pay compensation (s. 150 BLA 2006), increment, bonus, and other remunerations are the provisions mentioned under the labour legislation of Bangladesh.

2.2 Non-monetary data

Along with monetary factors, non-monetary factors are playing a vital role in satisfying workers (Sarker and Afroze 2014). Safety and security, secured job, appointment letter, washing and bathing facility, promotion policy, childcare facility, working hours, recreation facility, work without force, hygienic canteen, supervisor behaviour, leave facility, medical facility, working environment, social acceptance, and workers’ living standard may be categorised as the non-monetary factors.

Workers’ safety related provisions are drafted under the labour legislation (ss. 61-78A BLA 2006) in accordance with the health and safety related conventions of the ILO. Promotion of job security through retrenchment (s. 11 BLA 2006), discharge (s. 17 BLA 2006) and dismissal (s. 39 BLA 2006) guidelines, recruitment with appointment letter (s. 5 BLA 2006), and protection in the event of a company's insolvency are the provisions of current labour legislation in line with the ILO. Also, workers’ health and hygiene (ss. 51–60 BLA 2006), welfare (ss. 89–99 BLA 2006), working hours, and leave (ss. 100–119 BLA 2006) provisions are drafted in compliance with the ILO conventions.

3 Conceptual framework

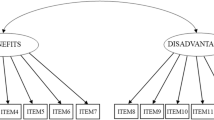

The conceptual model has been developed on primary and secondary sources including informal discussions with the garment workers in Bangladesh. Afterwards, the conceptual framework has been divided into two broad parts: pecuniary and non-pecuniary factors of labour dissatisfaction (Fig. 1).

In the setting of Bangladesh garments-manufacturing industry, work-satisfaction depends on both pecuniary and non-pecuniary factors. Workers’ health and hygiene, safety and security, wage and payment, welfare, and overall labour management significantly influence worker mind (Fig. 1). Above all, workers would be pleased if the national labour legislation is adhered to their industries.

In the context of Bangladesh garments-manufacturing industry, most of the workers are poor and illiterate. They work hard from dawn to dusk, but they cannot earn a liveable wage to cover their primary needs of food, shelter, clothes, and education. Thus, they are not satisfied with their work.

In fact, work-satisfaction depends on payment; so, when workers are not satisfied with their salary, they may not be satisfied with other benefit packages given by an establishment (Shabnam and Sarker 2012). In the same vein, Taylor (2008) shows that the work-satisfaction of workers also depends on other supportive financial benefits such as provident fund and other job benefits in addition to the monthly salary (Fig. 1).

Also, a study identifies five factors that have a direct impact on the work-satisfaction. These are: proper administrative supervision, affiliation with co-workers, nature of work, timely payment, and promotion of workers (Smith et al. 1969). Besides, Gürbüz (2009) shows that the work-satisfaction increases when a worker can rely on his/her supervisor, participate in a decision-making process, and recognise his/her job as motivating and rewarding.

Apart from the pecuniary benefits, Sarker and Afroze (2014) show that a non-pecuniary facet, for instance, workers’ unbiased evaluation, job description, job security, and flexibility plays an important role in satisfying workers in Bangladesh. Furthermore, Beckers et al. (2012) find that working hour and leave facilities are crucial for improving work-satisfaction of the workers.

Most importantly, the overall improvement of working conditions may play a significant role in work-satisfaction. All financial and non-financial factors mentioned above are part of the national labour legislation in Bangladesh. Thus, the application of labour law is indispensable for the satisfaction of the workers in this industry.

4 Methods

4.1 Target group

The workers who work full-time in Bangladesh's garments-manufacturing industry.

4.2 Time and location of the study

This research has been carried out in Bangladesh in November and December, 2019 in three upazilas: Savar and Ashulia (Dhaka District), and Gazipur Sadar (Gazipur District). These three upazilas were specifically chosen since they are known in Bangladesh as industrial centres for the garments industry (Syed et al. 2014).

4.3 Sampling technic

In these specific places, there was no comprehensive list of garment workers. As a consequence, data were collected using the Convenient Sampling Technique (CST). The CST was also employed in similar studies to gauge workers’ satisfaction in other industries of Bangladesh (Syed 2020a; Syed et al. 2021). A total of 208 workers were selected as samples for this study. Given the ethical issue, the participants had the option of answering or refusing to answer any question. Also, they had the option to be opted out at any point during the interview if they did not feel comfortable.

4.4 Data collection

Primary data were collected from the workers using a structured questionnaire administered by face-to-face interviews. Before collecting the data, a questionnaire was prepared and pre-tested. Afterwards, necessary modifications were made to the questionnaire on the basis of the pre-testing, and then, it was finalised. The structured questionnaire contained workers' perceptions that were measured by a separate variable on a 5-Point Likert scale. Point-5 indicates ‘strongly agree’, and point-1 indicates ‘strongly disagree’ with the statement. The duration of each interview varied from 10 to 15 min. As the workers in this industry did not understand English, the interviews were conducted in their native language (Bangla).

Data were collected mainly on the following aspects that include: (1) demographic status of the respondents; (2) pecuniary and non-pecuniary factors of the respondents; (3) opinions of the workers regarding their work-satisfaction in this industry. Furthermore, data were collected from Bangladesh Garments Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA), Bangladesh Knitwear Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BKMEA) regarding industry policies, and government establishments were also used to conduct an in-depth analysis.

4.5 Construction of the dependent variable

A 5-Point Likert Scale was used in several previous studies to assess the opinions of the workers regarding workers’ satisfaction (Mahmud et al. 2017; Kabir et al. 2018; Syed 2020a; Syed et al. 2021). In this study, using the Likert scale, an index of workers’ satisfaction was developed for workers, following Bangladesh Labour Act, 2006. From this index, 12 indicators relating to workers’ satisfaction have been categorised under the national labour legislation. The respondent workers were asked to provide their opinions about the 12 statements mentioned in the analytical part of the study. Each of the respondents was given a score of 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1 for strongly agree (SA), agree (A), neutral (N), disagree (DA), and strongly disagree (SDA), respectively, for each of the statements. Therefore, the overall satisfaction score for each worker lay within the range of 12–60 points.

4.6 Data reliability

Cronbach's alpha is a measure of internal consistency, which indicates how closely a set of variables in a group is related. It is considered to be a measure of scale reliability. If Cronbach’s alpha is nearer to 1, the reliability of measures is higher, according to Sekaran and Bougie (2010). The Cronbach's alpha is not calculated for each variable. Instead, it is calculated for all the variables in a combined fashion (Syed 2020a). In this study, Cronbach's alpha is 0.799, which indicates a very good level of internal consistency for the scale.

4.7 Analytical strategies

The Ordinary Least Square (OLS) method was used to assess the opinions of the workers about their facility enlisted by the labour legislation. In this study, the dependent variable is “workers’ work-satisfaction” with facilities drafted under the labour law in Bangladesh. The model can be specified as:

where Y = job satisfaction score of the employee; β0 = is constant; X1 = amount of salary for workers (BDT); X2 = timely pay salary (dummy: yes = 1 and no = 0); X3 = level of profit sharing to workers (BDT); X4 = workers’ increment policy (dummy: yes = 1 and no = 0); X5 = Leave facility for workers (dummy: yes = 1 and no = 0); X6 = supervisor behaviour with the workers (dummy: good = 1 and otherwise = 0); X7 = number of daily working hours of the workers; X8 = forces to work (dummy: yes = 1 and no = 0); X9 = working under congenial environment (dummy: yes = 1 and no = 0); X10 = number of hygienic canteen/lunchrooms for workers; X11 = job security for the workers (dummy: yes = 1 and no = 0); X12 = number of medical facility allowed to the workers; βi is the coefficient to be estimated, and μ is the error term of equation (1).

5 Results and discussion

5.1 Socioeconomic and demographic profile of the respondents

Workers of different ages are working in the industry. Respondents are classified into six separate groups of 15–20 years, 21–25 years, 26–30 years, 31–35 years, 36–40 years, and above 40 years. Out of 208 respondents, 83 are within the age group of 26–30 years, 57 are within 21–25 years, 26 are within 15–20 years, 20 are within 31–35 years, 16 are within 36–40 years, and only 6 workers are above 40 years of age (Table 1).

Respondents with different work experiences are classified into four separate groups having 1–3 years, 4–6 years, 7–9 years, and above 9 (nine) years of work experience. Out of 208 respondents, 78 have 1–3 years, 69 have 4–6 years, and 35 have above nine years of work experience. Whereas 26, the lowest number of workers, have 7–9 years of work experience (Table 1).

The education of the respondents is classified into five separate groups having PSC (Primary School Certificate, 5-year long), JSC (Junior School Certificate, 8-year long), SSC (Secondary School Certificate, 10 years long), HSC (Higher Secondary School Certificate, 12-year long), and Degree (above 12-year long education). Out of 208 respondents, 76 are PSC qualified, 70 are JSC, 41 are SSC, 20 are HSC, and only one worker is Degree qualified (Table 1).

The number of female workers is higher than that of male workers in the industries. However, female workers are passive compared to male workers when it comes to sharing their knowledge or experience. As a result, female respondents are fewer in number compared with male workers. Among the respondents, 109 are males, and 99 are females (Table 1).

There are four types of marital status of the respondents. Out of 208 respondents, 164 are married, 30 are single, 13 are divorced, and only one is separated, irrespective of male and female workers (Table 1).

In some cases, the husband and wife both are working in the garments-manufacturing industry to meet their basic needs. In most cases, each worker has three or four family members. Respondents' family members are categorised into three separate groups of two people, 3–4 people, and 5 or above. Out of 208 respondents, 115 declare that they have, on average, 3–4 members in each family, 66 respondents have 5 members and more while 27 respondents have two members in each family (Table 1).

5.2 Key factors of workers’ satisfaction

This study observes that out of the 12 independent variables, seven variables are significantly related to the dependent variable (Table 2). These seven variables are: (1) amount of salary received by the workers; (2) timely pay salary to the workers; (3) increment policy for the workers; (4) supervisor behaviour to the workers; (5) friendly working environment provided to the workers; (6) number of hygienic canteen/lunchrooms for the workers; and (7) number of medical facilities received by the workers (Table 2).

Pecuniary benefits are directly correlated with the work satisfaction of the workers. With regard to monetary factors, workers are more concerned with three aspects of salary: salary amount, timely payment of salary, and increment policy (Table 2).

Workers’ liveable minimum wage is crucial for work satisfaction. It is also rational to think that in the setting of a developing country like Bangladesh, workers’ satisfaction may not be fulfilled without a reasonable minimum wage. It can logically be assumed that a worker who receives a liveable minimum wage would be in a more advantageous position in earning income and spending than a worker who does not have this facility. This study also reveals that the workers’ wages as per labour law have a significant and positive impact on the dependent variable. It discloses that if one unit of salary is increased, employees’ satisfaction score will increase by 0.189 unit (Table 2). The finding of this study is consistent with several studies (Lydon et al. 2002; Bossler and Broszeit 2017; Krumbiegel et al. 2018). Similarly, Ashik-Uz-Zaman (2021) observed that receiving satisfactory amount of salary by workers played a vital role in improving their work efficiency. It is also relevant to think that a satisfactory wage or salary may not satisfy the workers if it is not paid timely. Everyone prefers to be paid on time, so it's not surprising that a payment delay can have a negative influence on employee morale, and as a result, it will increase staff attrition. A standardised pay process and consolidated data with an automated payroll system will achieve efficient and real outcomes rapidly. The timely payment of salaries in accordance with labour legislation had a considerable and beneficial impact on the dependent variable, according to this study. It is demonstrated that increasing wage payment in time by one unit will boost employee satisfaction by 0.258 unit (Table 2). It can logically be assumed that a worker who receives wages timely, would be in a more advantageous position in spending on their necessaries such as food, housing, shelter and other essential items. Thus, timely payment of salary will increase work-satisfaction.

Further, a salary increment, often known as a salary raise, is a component of an employee's annual pay that differs from a bonus. To revise the salary and yearly increment, the important factors are cost of living, standard of living, inflation, nature of work, risk and standard, socioeconomic conditions of the country, and the locality. It stands to the reason that people are better satisfied with their jobs after a wage increase. In line with the argument, this study exposes that the yearly increase in salary in line with the inflation of living costs has a significant and positive impact on the dependent variable. Increasing the annual increment in time by one unit is predicted to increase employee satisfaction by 0.103 unit (Table 2).

Among the seven significant variables, four are non-monetary factors that are supervisor behaviour, working environment, hygienic canteen facility, and medical facility, which are positively influencing workers’ satisfaction (Table 2).

The process of monitoring people's ability to accomplish the goals of the organisation in which they work is known as supervision. It could include things like analysing their workload, establishing expectations, monitoring and evaluating their performance, identifying learning and development opportunities, and keeping them up to date on company news. Many prior studies have looked at the issue from many angles and discovered a significant link between supervisory good behaviour and employees’ work satisfaction (Falcione et al. 1977; Teas 1983; Miles et al. 1996; Griffin et al. 2001). According to a recent study, employee well-being, work happiness, and organisational commitment are all influenced by perceived supervisor leadership (Mathieu et al. 2016). Thus, it is expected that the garments supervisors' good behaviour towards the workers would increase their work-satisfaction. This study also confirms that supervisors’ behaviour was positively and significantly related to the dependent variable ‘work-satisfaction’. It indicates that 0.339 units will increase the workers' satisfaction for each additional good behaviour of the supervisor (Table 2). It is rational to think that any intrinsic or extrinsic issues including financial or non-financial factors may not satisfy workers when they are not satisfied with the act of their supervisors.

The business must meet the needs of its employees by providing friendly working conditions in order to promote efficiency, effectiveness, productivity, and work dedication (Giridharan 2015). A friendly work environment allows employees to form meaningful bonds with their co-workers and share one’s thoughts and opinions. It demonstrates empathy and concern for their well-being as individuals as well as co-workers. It also takes time to get to know their families and their objectives. Thus, it can logically be assumed that a congenial working environment would increase workers’ satisfaction. Consistent with this assumption, the study finds that workers employed in usual working conditions are more satisfied with their workplace conditions than workers who work in stressful working circumstances (Bakotic and Babic 2013). Previous studies also find a link between a congenial workplace and work satisfaction (Chowdhury 2019; Fida et al. 2019; Taheri et al. 2020; Olanipekun 2021).

This study also reveals that a congenial working environment has a positive and significant influence on the dependent variable, as expected. It indicates that if a one-unit friendly working environment is increased, employees’ work satisfaction scores will increase by 0.372 unit (Table 2). Consistent with this result, a study finds a link between the working environment and employees’ work satisfaction (Raziq and Maulabakhsh 2015). Their research finishes with some brief recommendations including the necessity for businesses to recognise the value of a friendly working environment in boosting workers’ satisfaction.

The labour law has provisions to provide hygienic canteen facilities to workers. A sufficient number of canteen facilities with standard construction, accommodation, furniture, and other required equipment must be supplied when more than 100 persons are employed (s 92 BLA 2006). Furthermore, according to ILO, worker welfare facilities in terms of canteen, transportation, and rest, including workers' recreation facilities (excluding vacation) would be beneficial (Preamble, Recommendation No. 102). Constructing well-equipped and well-furnished canteen facilities for employees can provide them with the opportunity to eat fresh food in a clean and healthy environment. It goes without saying that having an adequate number of lunchrooms on the company premises can help employees save time and energy that they would otherwise lose by going outside to eat. This study finds that the number of workers' canteens facility is positively and significantly related to the dependent variable. It reveals that if a hygienic canteen facility is increased, employees’ work-satisfaction scores will increase by 0.176 unit (Table 2). In line with this finding, many studies demonstrate a positive relationship between canteen availability and workers’ satisfaction (Bhati and Ashokkumar 2013; Murugan et al. 2017).

Medical facilities in this study refer to the number of doctors and nurses employed by companies for the workers, as well as the number of medical appliances (first-aid box, medicine, x-ray machine, ambulance, and so on) used for the workers. Workers in Bangladesh, like those in other developing countries, frequently fail to receive adequate healthcare because of insufficient income and a lack of medical facilities in their neighbourhood or community (Rana 2014). Furthermore, workers in Bangladesh, particularly female workers, are still largely unaware of their healthcare options (Rana 2014). As a result, the study recommends that health insurance and health education programmes be implemented to help female garment workers with their health issues (Paul-Majumder 1996). According to Bangladeshi labour laws, it is the responsibility of employers to ensure the healthcare safety of their employees by providing them with adequate medical facilities in the workplace. It stands to reason that a worker who receives more medical services from his or her employer will be more physically, psychologically, and economically satisfied than a worker who receives few medical services. This study also finds that workers who received medical care as per labour law have a positive and significant relationship with the dependent variable (Table 2). Although workers' satisfaction level of working in their workplace is always neglected (Gaffar Khan et al. 2019), this study exposes that 0.247 unit would increase workers' satisfaction for each additional one unit increase in healthcare or medical services. The findings of this study are also consistent with those of Bhati and Ashokkumar (2013) and Akhter et al. (2017).

Thus, it can be summarised that the pecuniary and non-pecuniary factors are equally important for satisfying Bangladesh garment workers, which creates new literature in this paper. Furthermore, it is noted that all the significant pecuniary and non-pecuniary factors mentioned above are the provisions of the current national labour legislation, and ILO Conventions. Therefore, the state is responsible and obliged to ensure the above rights of the garment workers in Bangladesh.

6 Limitation of the study

It is a quantitative study that uses inferential research technic to find the factors under the labour legislation, which influence the satisfaction of global garments supply chain workers in Bangladesh. The findings of this study are on the basis of data collected with the 5-Point Likert Scale structured questionnaire. As a result, some evidence may be missed due to the absence of qualitative information. Therefore, it recommends comprehensive analysis by a qualitative study using interdisciplinary empirical legal research having an interpretative phenomenology, focus group discussion, and key informant interview technic. So, a thorough investigation is required for macro-level analysis and sound argumentation for further study.

7 Conclusion and implications

This study mainly focuses on some factors picked up from the national labour legislation in Bangladesh, which influences the labour satisfaction of global readymade garments workers in Bangladesh. Though previous literature demonstrates different factors that influence workers’ satisfaction, the current trend of garments workers’ satisfaction primarily relies on financial factors (salary, timely payment of salary, and yearly increment) along with some non-financial factors (supervisor behaviour, working environment, hygienic canteen facility, and medical facility). The study demonstrates that setting and practising monetary factors and non-monetary factors in line with current labour policy can increase labour satisfaction in this industry.

Most of the garment workers are poor, illiterate, and come from remote rural areas (Syed 2020b). They may not be satisfied without adequate monetary benefits. Also, the sampled workers in this study are not exceptional to it. Table 1 of respondents’ demographic description shows that in many cases, about four to five family members depend on the income of a worker. Thus, it is essential to take steps to increase monetary benefits and to set liveable minimum wages among the workers in accordance with the labour law in Bangladesh. For doing so, Minimum Wages Board should take into account the living cost, living standard of workers as well as their dependent family members for setting minimum wages. Besides, production cost, productivity, product price, inflation, nature of work, risk, and business capability may also be considered for setting liveable minimum wages. Furthermore, socio-economic conditions of the country, the locality concerned and other relevant factors should be taken into account for fixing minimum wages for workers in the industry. In many circumstances, it is evident that buyers from various countries are not ethically correct in setting a reasonable price for garments-manufacturing products made in Bangladesh (Syed 2020c). Thus, buyer associations including Accord (European) and Alliance (North American) may be placed under a strict policy to set a reasonable price for made-in Bangladesh garments-manufacturing products.

The focus should be given to providing non-monetary factors as well. As most of the garment workers are illiterate, they have no frequent alternative options to get other jobs. It is also rational to think that Bangladesh as a developing country, is unable to employ millions of illiterate workers within a limited scope of employment opportunities. As a result, workers are harassed by their employers in many aspects. So, employers’ behaviour is important to promote work-satisfaction of the workers.

As workers in this industry have no adequate liveable wages to meet their basic needs of food, shelter, health, and education (Syed 2018), it is important to provide the necessary healthcare facilities i.e., free medical check-ups. Emphasis should also be given to providing healthcare insurance policies for all workers.

Steps should also be taken to establish adequate numbers of hygienic canteen facilities, i.e., neat and clean lunchrooms for the workers. The canteen facilities including a fresh drinking water facility and a cooling system, as well as a proper seating arrangement should be well-equipped.

Above all, emphasis should be put on establishing an overall friendly working environment in this industry. In addition to wages and over-time benefits, supervisor behaviour, hygienic canteen facility, and medical facility, the working environment should also include safety and security, job benefits and job security, fair appointment and promotion policy, workers’ participation in decision-making policy, welfare facility, and ensuring balance between input and output of the workers’ commitments to the industry. As industrial accident is a regular phenomenon in the garments industry in Bangladesh, necessary steps must be taken to establish a safety committee with the participation of the workers and other staff. It is also critical to ensure that the safety committee meets on a regular basis in order to be more functional. The authority should take steps to provide an adequate budget to the safety committee so that it can use this fund to install or purchase safety equipment as soon as possible.

Furthermore, for the sake of the workers' well-being, a group insurance policy should be purchased. Besides, the emphasis should be placed on penalty provisions (e.g., adequate compensation, penalty, incarceration or corporate criminal liability, etc.) for non-compliance with the labour provisions outlined in Bangladesh Labour Act, 2006.

Though seven variables are found significant, this study does not claim that a mere significant variable should be implemented for achieving work-satisfaction. Due to the limitation of the study in terms of time, place, number of variables, and error term of the equation, other factors might not show all variables significantly. Therefore, the factors that are not found significant may be implemented as a legislative provision under the labour law in Bangladesh.

Notes

A bonus is an amount of money added to wages as a reward for good performance. Specifically, a festival bonus is an amount of money payable on the eve of religious festivals.

References

Akhter S, Rutherford S, Kumkum FA, Bromwich D, Anwar I, Rahman A, Chu C (2017) Work, gender roles, and health: Neglected mental health issues among female workers in the ready-made garment industry in Bangladesh. Int J Women’s Health 9:571

Arslan M (2020) Mechanisms of labour exploitation: the case of Pakistan. Int J Law Manag 62(1):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLMA-07-2018-0145

Ashik-Uz-Zaman MAM (2021) Minimum wage impact on RMG sector of Bangladesh: prospects, opportunities and challenges of new payout structure. Int J Bus Econ Res 10(1):8

Asma A, Sangita BW, Rajib K, Zafar AM, Mahmuda P (2017) Issues in business management and economics. Issues Bus Manag Econ 5(2):25–36. https://doi.org/10.15739/IBME.17.004

Bakotic D, Babic T (2013) Relationship between working conditions and job satisfaction: the case of Croatian shipbuilding company. Int J Bus Soc Sci 4(2):206–2013

Bangladesh Labour Act (2006) XLII of 2006, ss 5; 51–60; 11; 17; 39; 61–78A; 89–99; 100–119; 108; 123 (1) (2); 138; 138 (6); 141; 150; 234 (a) (b) (1). https://ogrlegal.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/Bangladesh-labour-act-2006-english.pdf. Accessed 5 May 2020

Beckers DG, Kompier MA, Kecklund G, Härmä M (2012) Work time control: theoretical conceptualization, current empirical knowledge, and research agenda. Scand J Work Environ Health 38(4):291–297

Bhati PP, Ashokkumar M (2013) Provision of welfare under factories act & its impact on employee satisfaction. J Bus Manag Soc Sci Res 2(2):57–69

Bossler M, Broszeit S (2017) Do minimum wages increase job satisfaction? Micro-data evidence from the new German minimum wage. Labour 31(4):480–493

Chowdhury S (2019) Impact of working environment on job satisfaction at accfintax. Internship report. BRAC Business School, BRAC University, Bangladesh. http://dspace.bracu.ac.bd/xmlui/handle/10361/12242

Dharmasri W, Vathsala W (2012) Effects of perceived organizational support on participation in decision making, affective commitment and job satisfaction in lean production in Sri Lanka. J Manuf Technol Manag 23(2):157–177. https://doi.org/10.1108/17410381211202179

Falcione RL, McCroskey JC, Daly JA (1977) Job satisfaction as a function of employees’ communication apprehension, self-esteem, and perceptions of their immediate supervisors. Ann Int Commun Assoc 1(1):363–375

Fida MK, Khan MZ, Safdar A (2019) Job satisfaction in banks: significance of emotional intelligence and workplace environment. Sch Bull 5(9):504–512

Gaffar Khan A, Ul Huq SM, Islam N (2019) Job satisfaction of garments industry in a developing country. Manag Stud Econ Syst 4(2):115–122

Giridharan KS (2015) Employees' levels of job satisfaction Int Res J Adv Eng and Technol. http://www.irjaet.com/Volume1-Issue-2/paper3.pdf

Griffin MA, Patterson MG, West MA (2001) Job satisfaction and teamwork: the role of supervisor support. J Organ Behav 22(5):537–550

Guest D (2002) Human resource management, corporate performance and employee wellbeing: building the worker into HRM. J Ind Relat 44(3):335–358

Gürbüz S (2009) The effect of high-performance HR practices on employees’ job satisfaction. Istanb Univ J Sch Bus Adm 38(2):110–123

Hechanova MRM, Manaois JO (2020) Blowing the whistle on workplace corruption: the role of ethical leadership. Int J Law Manag 62(3):277–294. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLMA-02-2019-0038.Accessed2May2021

Hermawan I, Msi SP (2011) Analisis ampak Kebijakan Makroekonomi Terhadap Perkembangan Industri Tekstil Dan Produk Tekstil Indonesia. Bull Monet Econ Bank 13(4):1–28

Hinkin TR, Schriesheim CA (1994) An examination of subordinate-perceived relationships between leader reward and punishment behavior and leader bases of power. Hum Relat 47(7):779–800

Hirsch BT, Schumacher EJ (1995) Monopsony power and relative wages in the labor market for nurses. J Health Econ 14(4):443–476

Junaimah J, See LP, Bashawir AG (2015) Effect of manager’s bases of power on employee’s job satisfaction: an empirical study of satisfaction with supervision. Int J Econ Commer Manag 3(2):1–14

Kabir GMS, Mahmud KT, Hassan A, Hilton D, Islam SM (2018) The role of training in building awareness about formalin abuse: evidence from Bangladesh. Int J Islam Middle East Finance Manag 11(1):96–108

Khatun F, Moazzem KG (2007) Poshak Shilpe Nunyatama Majuri: Preksit Bangladesh. Minimum Wage in the RMG Sector: perspective on Bangladesh. Bangladesh Unnayan Shamiksha, 1413, No. 33.

Kohpaiboon A (2003) Foreign trade regimes and the FDI-growth nexus: a case study of Thailand. J Dev Stud 40(2):55–69

Krumbiegel K, Maertens M, Wollni M (2018) The role of fairtrade certification for wages and job satisfaction of plantation workers. World Dev 102:195–212

Lydon R, Chevalier A (2002) Estimates of the effect of wages on job satisfaction (No. 531). Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics and Political Science, London

Mahmud KT, Parvez A, Alom K, Wahid IS, Hasan MK (2017) Does microcredit really bring hope to the female borrowers in Bangladesh? Evidence from the agribusiness program of BRAC. J Poverty 21(5):434–453

Mathieu C, Fabi B, Lacoursiere R, Raymond L (2016) The role of supervisory behavior, job satisfaction and organizational commitment on employee turnover. J Manag Organ 22(1):113–129

Miles EW, Patrick SL, King WC Jr (1996) Job level as a systemic variable in predicting the relationship between supervisory communication and job satisfaction. J Occup Organ Psychol 69(3):277–292

Ming G, Ganli L, Fulei C (2014) High-performance work systems, organizational identification and job satisfaction: evidence from China. Pak J Stat 30:5

Murugan P, Rajanbabu R, Raman GS, Vembu NR, Srinivasan GU, Auxilian A (2017) Job satisfaction and quality of work life of employees in Tirupur textile industries—a pivotal focus. Int J Econ Res 14(7):383–394

Olanipekun LO (2021) Effect of work environment and employees job satisfaction in selected branches of Lapo Micro-Finance Bank in Lagos State. LC Int J Stem 2(3):6–20

Paul-Majumder P (1996) Health impact of women’s wage employment: a case study of the garment industry of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Development Studies, Dhaka, pp 59–102

Rana M (2014) A study on labor welfare center and its implications for labor welfare in selected areas of Dhaka. Doctoral dissertation, University of Dhaka. http://repository.library.du.ac.bd:8080/bitstream/handle/123456789/1487/Juwel%20Rana.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 2 May 2021

Raziq A, Maulabakhsh R (2015) Impact of working environment on job satisfaction. Procedia Econ Finance 23:717–725

Sarker AR MD, Afroze R (2014) Can HRM practices improve job satisfaction of ready made garment (RMG) workers in Bangladesh? An alternative solution to recent unrest. Int J Bus Manag 9(10):185

Sekaran U, Bougie R (2010) Research methods for business: a skill building approach, 5th edn. Wiley, New York

Shabnam S, Sarker AR (2012) Impact of CSR and internal marketing on employee job satisfaction and organisational commitment: a case study from export-oriented SMEs in Bangladesh. World J Soc Sci 2(7):24–36

Smith PC, Kendall LM, Hulin CL (1969) The measurement of satisfaction in work and retirement. Rand McNally, Chicago

Syed RF, Bhattacharjee N, Khan R (2021) Influential factors under labor law adhere to ILO: an analysis in the fish farming industry of Bangladesh. SAGE Open 11(4):21582440211060668

Syed RF (2020a) Job satisfaction of shrimp industry workers in Bangladesh: an empirical analysis. Int J Law Manag 62(3):231–241. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLMA-05-2018-0104

Syed RF (2020b) Comparative implementation mechanism of minimum wage policy with adherence to ILO: A review of the landscape of garment global supply chain industry in Bangladesh. E-J Int Comp Labour Stud 9(3). ADAPT University Press. ISSN 2280-4056

Syed RF (2020c) Ethical business strategy between east and west: an analysis of minimum wage policy in the garment global supply chain industry of Bangladesh. Asian J Bus Ethics 9(2):241–255

Syed RF (2018) Minimum wage policy for garment manufacturing workers in Bangladesh. LLM Thesis, School of Law, University of Ottawa, Canada

Syed RF (2015) Working condition of the readymade garments workers in Bangladesh: an empirical analysis. Institute of Research and Training (IRT), Southeast University, Dhaka, Bangladesh. A research project funded by Southeast University (SEU). Available at IRT Archive

Syed RF, Asaduzzaman M, Emdadul H, Repon K, Abu-Noman MAA, Ayub A, Zafrin A, Liton C.B, Syed DH (2014) Security and safety net of garments workers: need for amendment of labour law. A study report of National Human Rights Commission, Bangladesh. http://nhrc.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/nhrc.portal.gov.bd/page/348ec5eb_22f8_4754_bb62_6a0d15ba1513/Security%20and%20Safety%20Net%20of%20Garments%20Workers.pdf. Accessed 1 Aug 2018

Taheri RH, Miah MS, Kamaruzzaman M (2020) Impact of working environment on job satisfaction. Eur J Bus Manag Res. https://doi.org/10.24018/EJBMR

Taylor S (2008) People resourcing, 4th edn. CIPD, London

Teas RK (1983) Supervisory behavior, role stress, and the job satisfaction of industrial salespeople. J Mark Res 20(1):84–91

Thomas L, Gail P, Vijay KS (2010) Culture, industrialization and multiple domains of employees job satisfaction: a case for HR strategy redesign in India. Int J Hum Res Manag 21(13):2438–2451. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2010.516595

Sadovský Z, Matějková J (2019) Minimum wage in the Czech Republic, and theoretical and practical aspects of public finance proceeding of the 24 international conference, Praha. University of Economics, Prague Faculty of Finance and Accounting, Department of Public Finance

Zohir SC (2007) Role of Dhaka export processing zone: employment and empowerment. Research Report, Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies, Dhaka

International Instruments

International Labour Organization, (ILO 1919) https://www.ilo.org/asia/about/WCMS_377171/lang--en/index.htm. Accessed 17 Apr 2021

The minimum wage fixing convention, 1970 (No. 131) with special reference to developing countries (entered into force: 29 Apr 1972). Adoption: Geneva, 54th ILC session (22 June 1970) https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:312276. Accessed 17 July 2021

The minimum wage-fixing machinery convention, 1928 (no. 26). Entry into force: 14 Jun 1930. Adoption: Geneva, 11st ILC session (16 June 1928). http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C026. Accessed 30 June 2021

The minimum wage fixing recommendation, 1970 (No. 135) with special reference to developing countries. Adoption: Geneva, 54th ILC session (22 Jun 1970). https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:::NO:12100:P12100_ILO_CODE:R135:NO. Accessed 3 July 2021

The minimum wage-fixing machinery recommendation, 1928 (No. 30). Adoption: Geneva, 11st ILC session (16 June 1928). http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:12100:0::NO::P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID,P12100_LANG_CODE:312368,fr:NO. Accessed 12 July 2021

Welfare facilities recommendation, 1956 (No. 102). Adoption: Geneva, 39th ILC session (26 June 1956). https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:312440

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest with the content of the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Syed, R.F., Mahmud, K.T. Factors influencing work-satisfaction of global garments supply chain workers in Bangladesh. Int Rev Econ 69, 507–524 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-022-00403-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-022-00403-6