Abstract

Despite the increasing recognition of the significance of children’s own perceptions of inequality and critical theorisations of, and much research on, the impact of inequality on human agency, there is a lack of empirical evidence on the impact of inequality on children’s agency. This paper contributes to addressing this gap by exploring how children’s perceptions of inequality impinge upon their perceptions of the efficacy of their agency with regard to their occupational choices. It uses questionnaire data from a sample of 862 South Korean school children aged 10–18 from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds and follow-up semi-structured interviews with 42 selected children. The findings suggest that, while most of the children held meritocratic beliefs about academic and economic inequalities, some subtle but significant relationships existed between the children’s perceptions of inequality, their socioeconomic status and their perceptions of their agency. The older children were significantly more likely both to be aware of their relative academic and economic positions and to have given up a desired occupation in response to their perceptions of the inefficacy of their agency. Across the sample as a whole, in the processes by which the children adjusted their future occupational ambitions, while their socioeconomic status (especially in terms of the father’s occupation) had a significant impact, the children’s awareness of their relative positions, especially their economic position, showed a more pervasive and significant relationship with their likelihood of having given up a desired occupation due to having perceived the inefficacy of their agency.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

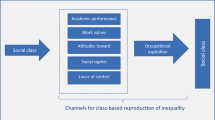

While it is widely accepted that the ways in which individuals perceive and experience their social worlds are influenced by the structural conditions of their lives, some critical theorists go further to suggest that those with materially disadvantaged living conditions form views or dispositions which lead them to ‘accept’ things as they are or to ‘choose’ to do things that perpetuate their situation, so contributing to the intergenerational reproduction of inequality (e.g. Bourdieu 1990a, 1990b; Freire 1996). However, while such theorisations of the impact of inequality on human agency have significant implications for childhood development, there is limited empirical evidence on whether and how this process may impact on children especially as they age. This, together with the increasing attention to children’s own perceptions and experiences of inequality or, more often, poverty (e.g., Bonn et al. 1999; Ridge 2007; Redmond 2008; Bessell 2009; Crivello et al. 2012), which goes beyond the traditional focus in research on the impact of inequality in terms of children’s developmental and other life outcomes, warrants an investigation of the relationship between children’s perceptions of inequality and their senses of the efficacy of their agency.

By ‘agency’, we mean both an individual’s ability to make a choice and their ability to act upon it. It is now widely recognised that children can exercise agency as social agents (James and Prout 2015), although younger children’s capacity for ‘moral’ agency, which is associated with taking responsibility for one’s acts, is questioned. At the same time, children’s agency, as with that of adults, is socially embedded. This means that children’s choices and their capacity to act upon them are constrained and/or enabled by their social and socioeconomic positions and relationships and other material factors including their physical environment, while the relationships between these factors and the agent can vary in time (Valentine 2011; Oswell 2013). In another paper (Kim and Gewirtz, 2018), we have explored how structural inequality influences children’s perceptions of their agency and provided an extended discussion of the issues concerning researching children’s agency with regard to their occupational choices which we will not repeat here. In this paper, we focus on how children’s own perceptions of inequality appear in relation to their socioeconomic status and how such perceptions impinge upon their perceptions of the efficacy of their agency in achieving their occupational choices.

Data for this paper comes from a sample of South Korean school children aged 10–18.Footnote 1 We chose South Korea as the context for the study because, after several decades which combined rapid economic growth with relatively low levels of inequality (Fields and Yoo 2000), a more recent rise in inequality alongside declining perceptions of the possibilities for upward social mobility (Min and Lee 2017) have become major public concerns. In this context, our study sought to explore how processes associated with the reproduction of inequality may be occurring early on in the lives of South Korean children. More specifically, we were interested in the role played by children’s perceptions of inequality and the efficacy of their agency in processes of social reproduction.

Our main methodological approaches to investigating the topic are sociological. As described above, our conceptualisation of children’s agency is informed by sociological ideas and we examine and interpret our data mainly through sociological lenses. However, in doing so, we also draw useful insights from other fields, in particular, social psychological debates on children’s views of inequality and the relationship between these views and their academic and occupational outcomes. While there is little existing evidence on the relationship between children’s perceptions of inequality and their senses of agency, evidence on the relationship between perceptions of inequality and some outcome dimensions can provide some useful insights into the former relationship. This is because children’s senses of their agency may be part of the mechanism that explains the relationship between their views on inequality and their outcomes.

2 Children’s Perceptions of Inequality

Children’s views on the causes of inequality are of particular interest to this paper because these may provide insights about their views on how people’s living conditions could be improved and, in relation to this, the efficacy of their agency to change them. Most studies of children’s views of socioeconomic inequality (i.e. those relating to differences in income or wealth) or of poverty have asked their participants about what being poor is like, what causes inequality or poverty and what people from certain socioeconomic groups are like (e.g. Betz and Kayser 2017; Hakovirta and Kallio 2016; Leahy 1990; Ramsey 1991) while, less frequently, children have also been asked how they think inequality or poverty might be addressed (e.g. Halik and Webley 2011; Leahy 1990).

A substantial body of research suggests that children as young as pre-primary school age show a consciousness of the differences associated with socioeconomic status although children’s beliefs about them become more complex as they get older (Bonn et al. 1999; Chafel and Neitzel 2005; Halik and Webley 2011; Leahy 1981, 1983a, 1983b, 1990; Ramsey 1991). With regard to the latter point, Hakovirta and Kallio (2016), for example, report in their study of Finnish children aged 10–15 that the younger children in their sample found it difficult to be analytical about the causes of poverty and tended to accept poverty and inequality as things that are just the way they are, while more analytical answers emerged among the older children who associated their causes with education, (un-)employment and/or occupational hierarchies.

Compared to research on age-related differences in children’s views on the causes of inequality, far less research is available on how such views vary by children’s socioeconomic backgrounds. In addition, where such research exists, the findings are inconsistent. For example, Furnham’s (1982) study of 15-year-old British state and private school children found that those who attended private schools (i.e., predominantly those from higher socioeconomic backgrounds) were more likely to cite individual factors (e.g. improvidence, poor financial management) as the causes of poverty rather than structural ones (e.g. a lack of available jobs). Likewise, Short (1991) found a similar result with younger British children in that those from middle-class backgrounds were more likely to think that income differences were legitimate, while Weinger (2000) also reported in the USA that middle-class children aged 5–14 viewed poor people in more negative terms and were more likely to blame them for their economic situation.

In contrast, in Flanagan and Tucker’s (1999) study of young people aged 12–18 in the USA, it was those from lower socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds, rather than those from more privileged ones, who were more likely to attribute poverty to individual factors. Leahy (1990) similarly observed in his study of children aged 6, 11, 14 and 17 years in the USA that, although lower-SES children were more likely to show concern for those who are poor, 17-year-old lower-SES boys were especially likely to view wealth as a function of an individual’s intelligence. While, more recently, Betz and Kayser’s (2017) study of German children aged 8–10 found their understanding of social stratification issues (i.e. differences in academic achievement and wealth and the relationships between the two) did not show any differences amongst those from different socio-economic backgrounds, this may have been partly due to the children being too young to have developed more class-specific and analytical views about the issues. The evidence on the effect of gender on children’s views of inequality does not present any consistent patterns although some studies suggest that girls show more awareness of it than boys (e.g. Bombi 1995; Ramsey 1991).

Different national contexts in association with their dominant discourses also appear to influence the development of children’s attitudes toward inequality, although research that allows for such comparisons is also limited. In Hakovirta and Kallio’s (2016) study of Finnish children, while some children identified individual factors as the reasons for poverty, the participating children overall were more likely to emphasise structural reasons, which the authors interpret as being due to them having ‘been socialised towards the ethos of the Nordic welfare state which underlines structural causes of social problems and the importance of equity’ (p.331). In comparison, other scholars have argued, especially in the context of the USA, that, while children progress towards more complex thoughts about social stratification, older children are more likely to be influenced by a meritocratic ideology that associates inequality with individual causes such as a lack of effort, motivation or talent (Leahy 1990; Neitzel and Chafel 2010).

It is not straightforward to ascertain whether views about the causes of inequality which focus on individual factors or those which stress structural factors are more conducive for encouraging individuals’ senses of their agency. This is because whether inequality is seen as mainly due to individual effort or innate characteristics or whether or not one accepts structural factors as they are can each have both positive and negative impacts on people’s senses of the efficacy of their agency.

3 Perceptions of Inequality and Individuals’ Outcomes

As the studies cited above suggest, children who notice inequality are not necessarily critical of it, with those who attribute it to individual factors tending to accept it as legitimate. Whilst there is little evidence from sociological research that directly focusses on whether and how children’s perceptions of inequality influence their own attitudes, actions and eventually outcomes, social psychological studies on the consequences of children’s ‘system-justifying’ beliefs shed some useful light on this issue. A system-justifying practice of attributing variations in poverty and wealth to individual, rather than structural, factors (Godfrey and Wolf 2016) is comparable to what in sociological debates is referred to as the contribution that meritocratic ideology makes to maintaining the status quo.

System justifying beliefs have been found to have different relationships with educational, experiential and occupational outcomes for individuals with different characteristics. For example, among German young people aged 12–21 in academically oriented secondary schools, such beliefs were associated with better grades and less stress at school (Dalbert and Stoeber 2005), while, among ethnically marginalised Latino college students in the USA, such beliefs were associated with lower grade point averages, although they were also negatively associated with students’ perceptions of discrimination and positively associated with their senses of belonging at the college (O’Brien et al. 2011). Godfrey et al. (2017) also found in the USA that children from low income families with system-justifying beliefs had worse trajectories between the 6th and 8th grades in terms of self-esteem, ‘delinquency’ and classroom behaviours, while Diemer (2009) found that poor and non-white young people who were more critically conscious of the structural forces which contributed to social unfairness attained higher status and better paying jobs in adulthood.

One of the factors that might help to explain the relationship between young people’s views of inequality and their educational and occupational outcomes may be young people’s perceptions of their agency. Those who have a low sense of the efficacy of their agency may be more likely to accept their living conditions and their levels of academic or other achievements and less likely to attempt to change them, with this leading to poorer academic and occupational outcomes. If so, what relationship exists between children’s perceptions of inequality as they get older and their senses of agency and how, if at all, does socioeconomic status mediate this relationship? These are the questions we explored in the study that is the focus of this paper. Before discussing how we conducted the study and its findings, we briefly discuss the South Korean context where the study was set.

4 Public Perceptions of Inequality and Individual Agency in South Korea

As a result of several decades of rapid economic growth, South Korea has been transformed from being one of the poorest countries in the world during the 1960s to one of the most industrialised today. In the first few decades of this growth, the economy produced many new middle-class jobs that could usually be achieved through education and/or hard work (Seth 2002; Sorensen 1994). This, alongside relatively low levels of income inequality, contributed to a strong public belief in the efficacy of individual agency. However, since the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s, income inequality has increased while public perceptions of the chances of social mobility have declined (Jain-chandra et al. 2016; Lee 2016; Min and Lee 2017). For example, the proportion of people aged 19 or older who think the possibility of intergenerational upward social mobility is low has increased from 11% in 1999 to 55% in 2017 (Statistics Korea 2009, 2017).

OECD (2018) suggests that the perceived and actual persistence of income inequalities in South Korea are both at just above the average of the OECD countries: it would take about five generations for a South Korean child from a bottom 10% household to reach the national average income, similarly to the UK, Italy, Portugal and the USA, whereas, in the Nordic countries, it would take under four. However, in a society where memories of widespread upward social mobility are still vivid, younger job seekers’ frustrations about their unfulfilled aspirations despite their high levels of education are reported to be high. Young adults, who perceive wealth to be more significant than hard work as a means of becoming successful (Kim 2018), classify themselves into different types of ‘spoons’ – specifically: gold, silver, bronze and earthen spoons.

This spoon-class classification seems to have originated on an anonymous Internet site and is based on the English expression that a privileged person is someone born with a silver spoon in their mouth. While there are various versions of the classification, a ‘gold’ spoon is often seen to be a person from a top 1% income/wealth household, whereas an ‘earthen’ spoon is someone who can expect no financial support from their parents upon graduating high school. Young people also call themselves ‘Saum-po-sae-dae’, meaning a generation which has given up three things – romance, marriage and childbirth – (Hankyoreh2017) while, more recently, owning a property, participating in social relationships, and having dreams and hopes have been added to this list.

5 Methods

While much has been written on how South Korean adults, including young adults who are entering or have experienced the job market, perceive inequality, there is relatively little research on South Korean children’s perceptions of inequality. To explore these, and their impact on children’s perceptions of the efficacy of their agency as they grow up and in relation to their socioeconomic status, we used questionnaires and semi-structured follow-up interviews to analyse in more depth the thoughts underlying the questionnaire responses.

The questionnaires were collected from 862 non-randomly sampled children aged 10–18, including those in Years 4~6 in primary school and those in all 3 year groups in middle (lower secondary) and high (upper secondary) schools. 42 children were selected for a follow-up interview from those who had completed the questionnaire and expressed an interest in participating in an interview. The questionnaires were administered in August and September 2017 in Seoul (the capital and largest city) and a small coastal city in the southwest (hereafter, ‘City 2’). Both the cities and the participating schools were chosen to include a wide range of children’s characteristics in the sample.

When investigating their perceptions of inequality, existing studies have usually asked children questions which were not focused on themselves (e.g. ‘how is it that some people have money and some people don’t?’ in Hakovirta and Kallio 2016). As Weinger (2000) suggests, asking such questions may let children be more open and expressive, but children’s views about other people may not necessarily correspond to those concerning their own situation. In comparison, as described in more detail below, we asked questions about inequality with reference to the children themselves. As our participants answered the questions on a questionnaire, this may have reduced the possibility of them being less open about their views. In the questionnaire, to avoid leading the children’s responses, we did not mention the word ‘inequality’ or ask directly what they thought about it. Likewise, in the follow-up interviews, it was only after a child had mentioned the concept that the researcher used it too.

The questions from the questionnaire that are analysed in this paper included two questions (Qineq1 & Qineq2) and some supplementary questions which were designed to explore children’s perceptions of inequality and six questions to explore their perceptions of their agency (Qag1~Qag6) (see Table 1). Qineq1 and Qineq2 asked respectively whether the participant ever compared their academic achievement levels and their family’s economic conditions with those of others. These questions were used to identify children who were more aware of disparities in the two dimensions. The supplementary open-ended questions then asked why they thought these disparities had appeared between themselves and others.

The questions to explore children’s perceptions of their agency included Qag1 and Qag2 about their present perceptions of the efficacy of their agency in achieving their occupational choices and Qag3~Qag6 about past perceptions of their agency, which asked whether they had given up a desired occupation for the following four reasons, respectively: because they thought they did not have the required talent; because they thought they would not receive the required financial support; because they thought they would not be able to try hard enough; and because they did not know what to do about it.

A questionnaire and a one-off follow-up interview are not ideal for recording changes in children’s perceptions of their agency over time as under-reporting is very likely due to memory lapses and because children may not cognitively recognise such changes in perceptions. However, by using Qag3~Qag6, we hoped to address some of the limitations of using a cross-sectional rather than a longitudinal research design. Furthermore, the four questions were used to explore an aspect of agency in practice by investigating what children may have given up acting upon.

The questionnaire also collected the following information about the children to use as independent variables to explain their awareness of their relative academic and economic positions (Qineq1 & Qineq2) and their perceptions of the efficacy of their agency (Qag1~Qag6): their ages, genders, locations (city of residence), desired education levels, occupational choices and levels of happiness (on a 5-point scale) that they usually felt at home and in school. Although academic ability was also suspected to be a significant factor, we were unable to collect sufficiently reliable information on it. As measures of their socioeconomic status, the questionnaire asked about the children’s parents’ (or other guardians’) education levels and occupations.Footnote 2 While we attempted to collect household income data from the parents as a further indicator, this was only possible for a very small minority of the children, so it could not be used in the analysis.

Children’s desired education levels and parents’ education levels were classified into ‘graduate school or higher’, ‘4-year university’, ‘2-year college’, ‘high school’ and ‘middle school or lower’ and were coded 5 to 1. When classifying parental occupations, we adapted the UK Office for National Statistics Socio-Economic Classification. Initial analysis found the responses of children with parents in the ‘small employer/own account holder’ group (e.g. businessman/woman, self-employed, shop-owner) did not fit with the patterns appearing among those of the children from other groups. This parental occupation group included diverse people, judging from their education levels, their partners’ education levels and occupations and the problem was resolved when this group was divided into those who had a university education and those who did not, with the first sub-group being placed above the ‘intermediate’ occupation group. Children whose occupational choices fell into the ‘small employer/own account holder’ group were also categorised similarly using their desired education levels. All occupational data were consequently classified into ‘higher managerial/administrative/professional’, ‘lower managerial/administrative/professional’, ‘small employer/own account holder with university education’, ‘intermediate’, ‘small employer/own account holder without university education’, ‘lower supervisory/technical’, ‘semi-routine/routine’, and ‘not-in-employment’ and coded 8 to 1.

Children who were uncertain about their occupational choices left this part of the questionnaire blank, as they also did if they did not know (or did not want to write for unknown reasons) either or both of their parents’ education levels or occupations. While missing values for these variables ranged between 27.5% and 34%, we found no clear evidence that these non-responses were non-random. Yet, in analysing the data, and especially when replacing the missing values with the variables’ mean values, we entered the relevant dummy variables to see whether there was any significant difference between those who gave information for these variables and those who did not.

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the children’s characteristics for the whole sample and separately for those who answered either ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to Qineq1 and Qineq2 respectively. It also shows the results of t-tests/chi-square tests, indicating the variables where there were significant differences between the two answer groups for each question.

We conducted binary logistic regression analysis of the children’s answers to Qineq1 and Qineq2 to explore whether their awareness of their relative academic and economic positions significantly differed by any of our independent variables. We then conducted multiple regression analysis of their answers to Qag1~Qag6 which were coded 5 to 1 from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’, including their answers to Qineq1 and Qineq2 in the list of predictor variables. When conducting the multiple regression analysis, we compared outputs from three different methods – pairwise deletion, list-wise deletion and mean substitution of missing values. Because the occupation and education level variables were highly correlated, the former was used as it contributed to explaining slightly higher shares of the variances in the children’s answers (r2). While the three methods did not produce any substantially different r2 for the questions, we present the outputs from the mean substitution method as it produced more similar sizes of r2 to those from the pairwise method and used the largest numbers of cases in the analysis.

The 42 follow-up interviews were conducted with 24 children from Seoul and 18 children from City 2, of which 19 were boys and 23 were girls. The children were selected to reflect the diversity in the range of answers given on the questionnaire, while also reflecting as far as possible the characteristics of the overall sample. The interviews focused on investigating the reasons for and the contexts in which the participants gave their questionnaire responses, before moving on to probe for further issues depending on their answers. The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed thematically (see Braun and Clarke 2006). The interview data helped us to make inferences about the processes underlying the patterns that appeared in the questionnaire data.

6 Findings

6.1 Children’s Perceptions of Inequality

While the majority of the children responded that they compared themselves academically with others (Qineq1), only a minority reported that they compared their family’s economic conditions with those of others (Qineq2) (62% and 17.1% respectively). However, under-reporting regarding Qineq2 was suspected during the follow-up interviews, as some children talked about having compared their families’ economic conditions with those of others mentally but of having interpreted the question as asking whether they had done so overtly (this may also have applied to their answers to Qineq1). Such underreporting may also be due to a gap between children’s perceptions and experiences of socioeconomic differences and their cognitive recognition of these. If perceptions and experiences of inequality are socially embedded and embodied, individuals may not always clearly recognise such perceptions and experiences cognitively.

In the binary logistic regressions, our variables explained 7~9% and 7~12% of the variances in the children’s answers to Qineq1 and Qineq2 respectively. The modest amount of the variances explained may be partly because academic issues are a relatively prevalent concern for South Korean children, whereas the result for Qineq2 may reflect the underreporting issue described above. Yet, the regression analysis indicated that older children and girls were significantly more likely to compare themselves with others both academically and economically (see Table 3), suggesting that, with age, children become more conscious of academic and economic disparities involving themselves, while girls tend to do so more than boys. While the children who wanted to achieve higher levels of education and those who wrote their occupational choices (in comparison with those who did not) were significantly more likely to compare themselves with others academically, the children who were less happy at home and those whose mothers had a higher status job were significantly more likely to compare themselves with others economically.

Children’s awareness of their relative academic and economic positions did not necessarily mean they were critical of academic and economic inequality, although their answers concerning the causes of these inequalities suggested many of them had not thought deeply about the inequalities they noticed. The reasons cited by the children for academic disparities were, in order of frequency: hard work; innate intelligence; hard work combined with innate intelligence; intelligence combined with the effect of private supplementary education (i.e. ‘cram schools’ and/or private tutoring)Footnote 3; being focused or having determination; the effect of private supplementary education; having an effective learning style; and so on. The dominance of hard work followed by innate intelligence as the perceived reasons for high academic performance also appeared amongst those who reported that they compared themselves with others economically and those who wrote that socioeconomic inequality was caused by the intergenerational transmission of wealth.

The reasons the children cited for economic disparities included, in order of frequency: better-off people having a good or better-paying job; the intergenerational transmission of wealth (sometimes cited in combination with hard work and/or luck); better-off people having worked hard; better-off people being good at what they do; hard work combined with luck; fate and so on. Some of the reasons that they (including some high school students) gave were simply descriptive of what being rich (or poor) is like (e.g. having much money, frequently going on holiday), as was the case in some previous studies (e.g. Bonn et al. 1999; Chafel and Neitzel 2005), although more of the older children, and especially those in high school, mentioned the intergenerational transmission of wealth. Yet, it was not possible to categorise the children’s answers between those which emphasised structural and individual factors respectively because, in many cases, it was unclear which of these the child was indicating. For example, when a child’s answer was ‘because their parents have better-paying jobs’, we do not know what she/he thought the reasons were for someone having such a job – although, given the reasons for academic excellence that the children cited above, it is likely that they thought of individual factors.

Some children seemed to think that the intergenerational transmission of wealth was not necessarily unfair. Several children suggested that it required hard work or good management to maintain an inheritance, whilst some others suggested that, if wealthy individuals themselves had not worked hard, previous generation(s) may have done so to pass on their wealth. Overall, meritocratic beliefs concerning inequality appeared dominant among the children in this study.

6.2 Awareness of Relative Economic Positions and Perceptions of Agency

The variables in our multiple regression analysis explained 8.6~17.6% of the variances in the children’s answers to the questions about their perceptions of their agency (Qag1~Qag6, see Tables 4, 5, and 6). These modest amounts of the variances explained may reflect some underreporting (as discussed in the methods section above) and/or may be because young people’s perceptions of their agency do not go through considerable changes until they are closer to entering, or have entered, the job market. However, the patterns that did appear provide some useful insights into the subtle dynamics amongst children’s awareness of their relative academic and economic positions, their perceptions of the efficacy of their agency and some of the structural factors that contribute to these perceptions.

The children’s present perceptions of the efficacy of their agency in achieving their occupational choices were positive on average and not significantly different by age, while their greater senses of the efficacy of their agency concerning the possibility of achieving any job of their choice if they worked ‘hard’ indicated they had meritocratic beliefs (Qag1 & Qag2, Table 4). Yet, older children were significantly more likely to have given up a desired occupation for all the four reasons in Qag3~Qag6 (Tables 5 and 6), indicating that they were likely to be expressing their current positive senses of the efficacy of their agency about their occupational choices which were a result of adjustments over time. A similar pattern to the age factor appeared with the factor of whether the child compared herself/himself with others economically, with these two factors being the only significant predictors of children’s past perceptions of the inefficacy of their agency in all the four questions in Qag3~Qag6.

Whether a child compared themselves with others academically and whether they did so economically were not significant predictors of their present perceptions of their ability to achieve their occupational choices (Qag1 & Qag2, Table 4). Yet, while children who compared themselves with others academically were significantly more likely to have given up a desired occupation because they did not think they could try hard enough to achieve it (Qag5), those who compared themselves with others economically were significantly more likely to have given up a desired occupation for all the four reasons in Qag3~Qag6 (Tables 5 and 6). In line with the findings on the dominance of individual factors (especially hard work) in the children’s views of the causes of academic disparities, those who were more conscious of their relative academic positions were more likely to have given up a desired occupation due to feeling a low sense of their agency which they attributed to themselves (a lack of effort) rather than to external factors. In comparison, children’s awareness of their relative economic positions had a more pervasive and significant relationship with their past senses of the inefficacy of their agency which appeared to be derived from a wider range of perceived reasons including a lack of required talent (Qag3), a lack of financial support (Qag4) and a lack of (access to) information or guidance (Qag6) as well as a lack of effort (Qag5).

Other than awareness of their relative academic and economic positions and their age, the factors that had a significant relationship with children’s answers to at least one of the four questions about their past perceptions of their agency (Qag3~Qag6) included: the father’s occupation (in Qag5 & Qag6), the child’s degrees of happiness at home (in Qag4 & Qag5) or in school (in Qag3, Qag5 & Qag6), gender (in Qag3), geographical location (in Qag4), occupational choice (i.e. its status; in Qag3~Qag5) and whether the child had written an occupational choice or not (not writing it probably indicates a higher sense of uncertainty about their future; in Qag5 & Qag6). In particular, the significance of happiness that children usually felt at home and in school, which also had a significant relationship with their present senses of agency (in Qag1 & Qag2), suggests a close relationship between a sense of happiness and a sense of agency. Furthermore, the significance of the status of the child’s occupational choice (the higher the status of their chosen occupation, the less likely they were to have reported having given up a desired occupation) and whether they had written their occupational choice, independently of other structural factors as above, seems to suggest some role of non-structural factors in the children’s senses of the efficacy of their agency.Footnote 4

The questionnaire data suggest that, while children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds (in terms of the father’s occupation) were more likely to have given up a desired occupation as a result of feeling a sense of the inefficacy of their agency to achieve it, of those from similar socioeconomic backgrounds, those who were more conscious of their relative economic conditions were more likely to have done so. In relation to this, while the questionnaire data suggested that middle-class children could be as conscious of their family’s relative economic positions (or more so in terms of their mother’s occupation) as those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds (see Table 3), the follow-up interviews illustrated how such awareness might be associated with them giving up a desired occupation. These children, compared to those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, may be able to explore a wider range of options for their future but were also often conscious of the limits of, or constraints on, such explorations.

For example, Gina in high school Year 2 from Seoul, whose parents (both university-educated) ran and taught at a cram school, wrote on the questionnaire that she was not sure what she wanted to become in the future but, if anything were possible, she wanted to become a musician.Footnote 5 The interview with her explored her thoughts underlying these answers. Although her parents had said that a career in the music industry would be expensive to pursue, she felt that, if she had been firm about pursuing it, they would have supported her financially anyway (e.g. by paying for music lessons). Yet, Gina was not sure whether she was passionate enough about the dream to let her parents bear the costs associated with it, especially given that the field has uncertain prospects in terms of job stability and pay. She felt not pursuing the dream was a result of her lack of ‘passion’ rather than economic constraints. This perception was also expressed in her questionnaire responses where she ‘agreed’ that she had given up a desired occupation because she felt she was unable to try hard enough to achieve it (Qag5), whereas she ‘neither agreed nor disagreed’ with the other three reasons for having given up a desired occupation, including a lack of financial support.

The significance of children’s awareness of their relative economic positions which appears to apply to children from all levels of socioeconomic background, as described above, alongside that of structural factors, in the formation of their senses of the efficacy of their agency provides some insights into some of the mechanisms by which some children end up reproducing their parental socioeconomic status or perhaps even moving downwards.

6.3 Living out their Lives while Reproducing Inequality

As for the nature of inequality, most of the children interviewed appeared to focus on whether opportunities and processes were fair rather than on inequality in outcomes. Although they mentioned it or even suspected its impact upon themselves, for most children inequality often seemed to be a vague concept and something that they had not thought deeply enough about to form a coherent view. Children’s views on whether and how inequality might have affected themselves varied widely. Some children, mainly middle and high school students, were conscious of the influences of family backgrounds on individuals’ educational and career achievements and their own disadvantages concerning these. Although, on the questionnaires, a majority of these children had still agreed that they would be able to achieve a job of their choice (Qag1), it emerged in the interviews that a job of their choice in their answers to Qag1 was often one that they had settled on after having given up a previously desired and often higher status occupation (as was also reflected in their questionnaire responses to Qag3~Qag6).

A majority of the children interviewed were not entirely certain about the impact of inequality on themselves and, especially the younger ones, tended to think they were too young to have been affected by it yet. Meehae in high school Year 2 from City 2, whose family had been evicted from their rented accommodation and struggled to make ends meet every month (Meehae’s father was a factory worker and mother was a part-time cleaner), indicated a tentative view about it:

Researcher: You said the world seems to be unfair. Do you think that you have been affected by such unfairness?

Meehae: Hmm… have I been affected by it … as we are not rich, as we are on the side of being a little poor, in terms of benefits or getting opportunities, inequality might have been involved. I might have been affected by it, without my knowledge, one way or another…

…

Researcher: Have you felt any constraints about achieving what you want to become in the future?

Meehae: Well, I don’t know. I have not entered society yet. I may be too young to have experienced them. I am still in school and I just heard those things on the Internet and in the media, I don’t feel it myself. If I hear those things, I become uncertain whether they are constraints or not. When I get older and enter society, might I not then get to know better …

Although Meehae was unsure of whether she had experienced any constraints on achieving what she wanted to become, on her questionnaire, she had ticked ‘agree’ that she had given up a desired occupation because she did not think she would get the required financial support (Qag4) and because she did not think she could try hard enough (Qag5) – suggesting that her occupational choice (which she was currently unsure of) had been influenced by inequality. Although she was aware of her relative economic position, as was the case with the majority of the other children interviewed, this did not seem to have led to a clear recognition of the pervasive impact of inequality on herself. As Meehae also indicated in the extract, and despite long-standing criticisms of school education as a key means of the reproduction of socioeconomic inequality (Bourdieu and Passeron 1990; Bowles and Gintis 1977), some children thought the school and childhood are a space and a time which are isolated from wider society and adulthood when inequality would become significant.

One child interviewed said that one must accept one’s living conditions and that her socioeconomic conditions were beyond her own control (this attitude appeared to be in line with those of a few children who wrote ‘fate’ on their questionnaires for the reasons for wealth or poverty). Yujin in middle school Year 1 from Seoul, whose father was a salesperson of rubber products, doubted whether her own future would be any different.

Researcher: Have you heard somewhere or from someone that a person must live with whatever is given to them?

Yujin: I just thought that… it’s not something I can change…

Researcher: How did you get to think that?

Yujin: I just felt it. I might have got to know it when I was in primary school.

Researcher: Was there any event that let you ‘know’ that?

Yujin: No, not really…

We do not know whether there had, in fact, been an occasion which had led Yujin to think in the way she did, but she did not want to talk about it. However, towards the end of the interview, and in contrast to her previously passive attitude, Yujin expressed a strong determination to become an illustrator – ‘I want to devote all my life to becoming one’. Yujin had earlier dropped the idea of becoming a painter. Although she wrote on the questionnaire that this was because she had heard from her grandmother that becoming a painter would be expensive, in the interview she said an illustrator was now her preferred job. Yujin’s expression of agency (as was the case with the other children who responded positively about achieving their current occupational choices) may be more accurately described as an expression of ‘bounded’ agency (Evans 2002) – agency that is shaped by a person’s past experiences, current opportunities and perceptions of their possible futures.

In comparison, children from relatively affluent backgrounds were often aware of the benefits they enjoyed due to their families’ material affluence (e.g. expensive cram schools, cultural experiences including foreign trips). However, they also thought about those who might be even more advantaged than themselves and their own relative disadvantages, for example, by not having social capital relevant to the work they wanted to do in the future or the financial capital required for them to solely focus on achieving their dreams. Yunho, one such boy in high school Year 1 in Seoul, had parents whose combined income was well within the highest 1% of South Korean households (both were executives of well-known companies) – some might call him a ‘gold’ spoon. While he thought that becoming a lawyer, his current desired occupation, would mainly depend on individual ability and hard work, he also believed that becoming a successful lawyer would take more, suggesting that such lawyers were often individuals whose parents and/or other family members, unlike himself, had been successful lawyers for generations. Believing that meritocracy explained individuals’ chances of becoming a lawyer, he did not appear to recognise the benefits he enjoyed compared to those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Instead, his recognition of the role of social capital for succeeding at law illustrated how some children’s senses of their relative disadvantage diverged from their actual socioeconomic positions.

Yunho thought that structural inequalities in South Korea would not change soon, so all he could do in the current situation was to ‘just try to do [his] best’. While children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds were more likely to adjust their ambitions in response to their perceptions of the inefficacy of their agency, those from better-off backgrounds like Yunho, who were often ‘aware’ of inequality but did not as often and as fully recognise their relative advantages in getting ahead in life, sought to maintain or even enhance such advantages. In these ways, and while some children will still be socioeconomically mobile, it appeared that children from different socioeconomic statuses were living their lives in ways that contributed to reproducing inequality.

7 Conclusion

Our findings suggest that some subtle but significant relationships exist between South Korean school children’s perceptions of inequality, their socioeconomic status and their perceptions of their agency. While the older children were significantly more likely to be aware of their relative academic and economic positions, they were also significantly more likely to have given up a desired occupation in response to their perceptions of the inefficacy of their agency. Across the sample as a whole, in the processes in which the children adjusted their future occupational ambitions, while their socioeconomic status (especially in terms of the father’s occupation) appeared to have a significant impact, the children’s awareness of their relative positions, and especially their economic position, showed a more pervasive and significant relationship with their likelihood of having given up a desired occupation due to their senses of the inefficacy of their agency.

A majority of the children in the study appeared to hold meritocratic beliefs about academic and economic inequalities. Although some children, especially the older ones, mentioned inequality and its impacts on their educational and wider life prospects, the majority of the children were vague about or even unaware of inequality’s current and on-going impact upon themselves. It appeared that, while their awareness of inequality was possibly influenced by wider public discourses to which they would have been exposed, they were often vaguely optimistic about their future – in ways that may be characteristic of an early life stage (Rudd and Evans 1998) – despite, in some cases, the compromises in their future ambitions that they had already made. Without previous research to compare our findings to, it is not known whether increasing inequality and the public discourses surrounding it has increased children’s awareness of inequality. But what our findings do reveal is that such awareness, in conjunction with children’s perceptions of the inefficacy of their agency, is associated with their downward adjustments of their future ambitions rather than any attempts to overcome the challenges they encounter.

With this study as an impetus, further research could usefully examine whether the relationship between young people’s perceptions of inequality and their perceptions of the efficacy of their agency (and the mediating role of their socioeconomic background in this relationship) appears more distinctly as they get closer to entering, or have direct experience of, the job market. It would also be useful to explore whether children who think of inequality as an outcome of structural rather than individual factors are more or less likely to adjust their senses of the efficacy of their agency. Finally, further research is needed on whether critical views of inequality are indeed associated with better educational achievements and/or higher status or higher paying occupations, and if so, what specific factors and processes may work to influence the development of such critical views.

Notes

While the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child defines children as persons under the age of 18, when mentioning children, we include those aged 18 for the convenience of referring to all participants and because, in South Korea, persons reach the legal age of majority at 19.

Research shows that children aged about 11 provide valid information about their parents’ occupations (West et al. 2001; Vereecken and Vandegehuchte 2003). Furthermore, in our study, when comparing some of primary school Years 4~5 children’s questionnaires (which they filled in at school) and their parents’ questionnaires, where both sets were available, the information all matched except for a few cases when the children left the relevant questions blank.

While the effect of supplementary education is contentious, children from higher socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to participate in it (Cho and Park 2016).

In our other paper mentioned earlier, we discuss in detail some of the issues concerning these structural and non-structural factors and the processes by which children adjust their occupational choices as they grow up in response to their perceptions of the (in)efficacy of their agency to achieve them.

All names in this paper are pseudonyms to preserve participants’ anonymity.

References

Bessell, S. (2009). Indonesian Children's views and experiences of work and poverty. Social Policy and Society, 8(4), 527–540.

Betz, T., & Kayser, L. (2017). Children and society: children’s knowledge about inequalities, meritocracy and the interdependency of academic achievement, poverty and wealth. The American Behavioral Scientist, 61(2), 186–203.

Bombi, A. (1995). Social factors of economic socialization. In P. Lunt & A. Furnham (Eds.), Economic Socialization: The Economic Beliefs and Behaviours of Young People (pp. 183–201). Brookfield: Edward Elgar Publishing Company.

Bonn, M., Earle, D., Lea, S., & Webley, P. (1999). South African children’s views of wealth, poverty, inequality and employment. Journal of Economic Psychology, 20(5), 593–612.

Bourdieu, P. (1990a). The logic of practice. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1990b). In other words: Towards a reflexive sociology. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. (1990). Reproduction in education, society and culture (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (1977). Schooling in capitalist America: Educational reform and the contradictions of economic life. New York: Basic Books.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Chafel, J. A., & Neitzel, C. (2005). Young children’s ideas about the nature, causes, justification, and alleviation of poverty. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 20, 433–450.

Cho, Y., & Park, H. (2016). Shadow education and educational inequality in South Korea: Examining effect heterogeneity of shadow education on middle school seniors’ achievement test scores. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 44, 22–32.

Crivello, G., Vennam, U., & Komanduri, A. (2012). Ridiculed for not having anything: Children’s views on poverty and inequality in rural India. In J. Boyden & M. Bourdillon (Eds.), Childhood poverty: Multidisciplinary approaches. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dalbert, C., & Stoeber, J. (2005). The belief in a just world and distress at school. Social Psychology of Education, 8, 123–135.

Diemer, M. A. (2009). Pathways to occupational attainment among poor youth of colour: The role of socio-political development. The Counselling Psychologist, 37, 6–35.

Evans, K. (2002). Taking control of their lives? Agency in young adult transitions in England and the new Germany. Journal of Youth Studies, 5(3), 245–269.

Fields, G. S., & Yoo, G. (2000). Falling labour income inequality in Korea’s economic growth: Patterns and underlying causes. Review of Income and Wealth Series, 46(2), 139–159.

Flanagan, C. A., & Tucker, C. J. (1999). Adolescents’ explanations for political issues: Concordance with their views of self and society. Developmental Psychology, 35, 1198–1209.

Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the oppressed. London: Penguin Books.

Godfrey, E. B., & Wolf, S. (2016). Developing critical consciousness or justifying the system?: A qualitative analysis of attributions for poverty and wealth among low-income racial/ethnic minority and immigrant women. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22, 93–103.

Godfrey, E. B., Santos, C., & Burson, E. (2017). For better or worse? System-justifying beliefs in sixth-grade predict trajectories of self-esteem and behaviour across early adolescence. Child Development., 90, 180–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12854.

Hakovirta, M., & Kallio, J. (2016). Children’s perceptions of poverty. Child Indicators Research, 9, 317–334.

Halik, M., & Webley, P. (2011). Adolescents’ understanding of poverty and the poor in rural Malaysia. Journal of Economic Psychology, 32(2), 231–239.

Hankyoreh, 2017. Employed or not, 8 out of 10 young S. Koreans “exhausted” [online], 13 August. Available at: http://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_national/806570.html (Accessed 16 June 2018).

Jain-chandra, S., Kinda, T., Kochhar, K., Piao, S., & Schauer, J. (2016). Sharing the growth dividend: Analysis of inequality in Asia. IMF Working Paper WP/, 16(48).

James, A., & Prout, A. (2015). Constructing and reconstructing childhood: Contemporary issues in the sociological study of childhood (3rd ed.). Abingdon: Routledge.

Kim, C-Y., & Gewirtz, S. (2018). Adapted optimism and under-reported compromises: Children's perceptions of their agency regarding their occupational 'choices'. Project paper (under review with British Journal of Sociology of Education).

Kim, H-S. (2018). Dynamic Korea and Spoon-class theory (‘다이내믹 코리아’와 ‘수저계급론’), Narakyungje (나라경제), KDI, March 2018, pp.34–36. Available at: https://eiec.kdi.re.kr/publish/nara/column/view.jsp?idx=11455 (Accessed 1 May 2018).

Leahy, R. (1981). The development of the conception of economic inequality: I. Descriptions and comparisons of rich and poor people. Child Development, 52, 523–532.

Leahy, R. (1983a). Development of the conception of economic inequality: II. Explanations, justifications, and concepts of social mobility and change. Developmental Psychology, 19, 111–125.

Leahy, R. (1983b). The development of the conception of social class. In R. Leahy (Ed.), The Child’s construction of social inequality (pp. 79–107). New York: Academic Press.

Leahy, R. (1990). The development of concepts of economic and social inequality. New Directions for Child Development, 1990(46), 107–120.

Lee, K-K., (2016). The end of egalitarian growth in South Korea: Rising inequality and stagnant growth since after the 1997 crisis. Asia Future Forum, 24 November. Available from: http://www.networkideas.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Kang-Kook_Lee.pdf [Accessed 28 August 2018].

Min, I., & Lee, K.-H. (2017). Occupational mobility and inequality of opportunity. In Monthly Labour Review (Vol. 148, pp. 63–74). Korea Labour Institute.

Neitzel, C., & Chafel, J. (2010). And no flowers grow there and stuff: Young children’s social representations of poverty. Children and Youth Speak for Themselves: Social Studies of Children and Youth, 13, 33–59.

O’Brien, L. T., Mars, D. E., & Eccleston, C. (2011). System-justifying ideologies and academic outcomes among first-year Latino students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17(4), 406–414.

OECD. (2018). A broken social elevator?: How to promote social mobility. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Oswell, D. (2013). The agency of children: From family to global human rights. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ramsey, P. (1991). Young children’s awareness and understanding of social class differences. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 152, 71–82.

Redmond, G. (2008). Children’s Perspectives on Economic Adversity: A review of the literature. In Innocenti Discussion Paper No. 2008–01. Florence: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre.

Ridge, T. (2007). It’s a family affair: Low-income children’s perspectives on maternal work. Journal of Social Policy, 36, 399–416.

Rudd, P., & Evans, K. (1998). Structure and agency in youth transitions: Student experiences of vocational further education. Journal of Youth Studies, 1(1), 39–62.

Seth, M. J. (2002). Education fever: Society, politics and the pursuit of schooling in South Korea. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Short, G. (1991). Perceptions of inequality: Primary school children’s discourse on social class. Educational Studies, 17(1), 89–106.

Sorensen, C. (1994). Success and education in South Korea. Comparative Education Review, 38(1), 10–35.

Statistics Korea. (2009). 2009 social survey [online] Available at: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/pressReleases/11/5/index.board?bmode=read&bSeq=&aSeq=273277&pageNo=2&rowNum=10&navCount=10&currPg=&sTarget=title&sTxt= (Accessed 18 June 2018).

Statistics Korea. (2017). The summary result of 2017 social survey [online] Available at: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/pressReleases/11/5/index.board?bmode=read&bSeq=&aSeq=364927&pageNo=1&rowNum=10&navCount=10&currPg=&sTarget=title&sTxt= (Accessed 18 June 2018).

Valentine, K. (2011). Accounting for agency. Children & Society, 25(5), 347–358.

Vereecken, C., & Vandegehuchte, A. (2003). Measurement of parental occupation: Agreement between parents and their children. Archive of Public Health, 61, 141–149.

Weinger, S. (2000). Economic status: Middle class and poor children’s views. Children & Society, 14(2), 135–146.

West, P., Sweeting, H., & Speed, E. (2001). We really do know what you do: A comparison of reports from 11-year-olds and their parents in respect of parental economic status and occupation. Sociology, 35(2), 539–559.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the students who took part in this research and the teachers who facilitated their participation. Without them, the research in this paper would not have been possible. We also appreciate the useful comments from Sait Bayrakdar and John Owens on an earlier draft of this paper.

Funding

The research in this paper was supported by the Academy of Korean Studies grant (AKS-2017-R69).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, CY., Gewirtz, S. ‘It’s Not Something I Can Change…’: Children’s perceptions of inequality and their agency in relation to their occupational choices. Child Ind Res 12, 2013–2034 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-9624-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-9624-1