Abstract

Purpose of Review

Telemedicine has become popular as an alternative for in-person weight loss treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. This review focuses on weight loss interventions utilizing real-time telemedicine.

Recent Findings

Telemedicine interventions are usually run as a weekly counseling and educational session or as a complement to a primarily Web-based intervention. A wide variety of healthcare professionals may provide the intervention. Common content includes portion control, increased physical activity, and relapse prevention. Self-monitoring is associated with intervention success. Modalities considered include online chats, text messages, phone calls, and videoconferences. Videoconferencing may be especially useful in capturing the interpersonal connection associated with in-person care but is understudied compared to other modalities. While many interventions show improvements in weight and weight-related outcomes, small sample sizes limit generalizability. Technology access and digital literacy are both necessary.

Summary

Telemedicine interventions can successfully help patients with obesity lose weight. Telemedicine interventions provide a safe, remote alternative and may expand treatment access to hard-to-reach populations. Further research is needed on telemedicine weight loss treatments for seniors, men, and ethnic minorities, as well as on the impact of long-term interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: Telemedicine and Weight Loss in the Pandemic Era

The COVID-19 pandemic has been damaging for weight loss. There is some evidence that the COVID-19 has been associated with weight gain among adults [1]. This trend, a continuation of decades of elevated weight among American adults [2], illustrates the pressing need for weight loss interventions.

To provide safe care alternatives during the COVID-19 pandemic, many health systems suspended elective procedures and nonurgent outpatient visits. A large proportion of outpatients visits were converted to telemedicine appointments [3]. Telemedicine is part of a broad category of health interventions delivered via a digital health platform. Telemedicine is often used interchangeably with other digital health interventions such as virtual care, eHealth, and mHealth [4•]. Telemedicine in the USA grew an unprecedented 80% in 2020 [5]. Recent changes in legislation and reimbursement practices mean that telemedicine appointments are valued financially comparably to in-person medical appointments [6, 7]. Telemedicine also confers a number of advantages, including elimination of time spent traveling to appointments and in waiting rooms, and possibly greater ease for patients who do not need to leave their homes to seek medical care [8]. Telemedicine is expected to remain an integral part of future primary care, even after the current emergency has passed [9].

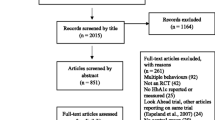

The purpose of this review is to describe published reports on telemedicine for the treatment of obesity. We defined telemedicine interventions as those involving real-time interaction with one or more weight loss professionals or peer leaders and in which counseling or other interventions are delivered remotely, with no in-person contact. Provider contact may be delivered via synchronous audio-visual videoconferencing, audio-only telephone or mobile phone contact, text messages, etc. Search terms used were “weight loss” and “weight loss maintenance,” paired with “telemedicine” or “videoconferencing,” using the search engines PubMed and GoogleScholar. Search criteria included English-language publications which described populations aged 18 or older, who were initially overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), with publication dates 2016–2021. Reviewed studies (see Table 1) were required to have weight-related outcome data, such as changes in body weight, daily energy consumption, or daily physical activity. Other outcomes, such as exercise self-efficacy and intervention satisfaction, were also extracted if available. Entirely automated online programs not including scheduled, real-time interaction with a healthcare provider were also excluded.

Prior Reviews of Digital Health Interventions for Weight Loss

Two important questions should be considered when utilizing telemedicine for weight loss. First, do telemedicine interventions lead to meaningful improvements in important weight loss metrics, such as body weight, energy intake, and physical activity? Houser et al. [10•] reviewed weight and weight-related outcomes in digital health interventions published 2010–2017. Sixty percent of reviewed studies reported statistically significant declines in weight. All the reviewed studies reported improvements in diet and physical activity, although few reached statistical significance. Alternately, a systematic review of systematic reviews by Sorgente et al. explored the efficacy of Web-based weight loss and weight loss maintenance interventions [11]. Web-based digital health interventions in which program content was delivered online with no provider contact were found to be more effective compared to control and/or minimal interventions, such as receiving a weight loss manual. Results were less definitive when comparing these Web-based interventions to telemedicine alternatives, with remote provider contact. Compared to solely Web-based interventions with no contact from program providers, face-to-face interventions, with tailored or clinician-lead feedback, led to better weight loss results [11].

Common Content

Successful weight loss interventions, both in-person and via telemedicine, have common features. Participants learn to reduce their daily energy intake in a safe, sustainable way. Healthcare professionals provide content and skill-building sessions in areas such as making healthy food substitutions, portion control, selecting and preparing healthy food, mindful eating, reduced “grazing” [12•], relapse prevention, and problem-solving [13]. Interestingly, while most studies encourage physical activity, few include guided training/exercise sessions.

One of the most frequently taught skills is self-monitoring. Many weight loss interventions encourage participants to frequently record their weight, steps per day, exercise sessions, and/or dietary details. Self-monitoring may take many forms including paper logs, uploading food diaries into a website, taking pictures of meals, or utilizing a fitness application (“app”). Digital scales and physical activity trackers have become especially popular options, both within professionally led interventions and for self-directed programs. As of May 2018, the most popular fitness applications, such as FitBit (27.4 million) and MyFitnessPal (19.1 million), have millions of active users in the USA [14]. These devices are well-suited to remote monitoring as they allow providers to access objective, real-time data and then provide tailored feedback. For example, in the TEAM intervention, participants used a Withings Activité Pop tracker and Body+ scale to self-monitor their weight, physical activity, and nutrition. Participants then received weekly feedback from a dietician and monthly medical feedback from a physician [15].

More frequent and sustained self-monitoring is associated with improved outcomes. For example, in West et al.’s comparison of text vs. videoconference weight loss groups [13], the videoconferencing group monitored their weight (123 days vs 8 days for text; p < 0.001) and physical activity (55 days vs 22 days) more frequently. The group which self-monitored more frequently (videoconferencing) was twice as likely to lose 5% body weight, although a small sample size (N = 32) precluded statistical significance.

Intervention Structure

Interventions have been structured in two ways. One is counseling sessions, often via videoconferencing, usually hour-long weekly meetings for 10–12 weeks. Interventions lasting longer than 6 months or those with more than 14 sessions tended to result in greater weight loss [16]. Usually during these sessions, healthcare providers present educational content and then discuss participants’ questions or challenges. This format is especially useful for group interventions allowing participants to provide each other with social support, brainstorm solutions together, and strive towards a common goal. In this format, the counseling sessions are the active component of the intervention, although they may be supplemented with other activities such as text messaging groups, online discussion boards, and online educational content available on-demand.

A second common format uses telemedicine as an adjunct or supplement to another primary intervention, most often an online program. Participants receive the bulk of the intervention online, which allows them to process the content at a time and pace of their choosing. Providers monitor progress, often via apps or remote monitoring devices, and provide feedback and support at regular intervals. The frequency of the feedback may vary; Project HELP provided 20-min telephone counseling sessions every 2 weeks [17], while the TEAM intervention provided weekly and monthly feedback [15].

The background of healthcare providers who deliver telemedicine weight loss intervention varies widely. The nebulous term “health coach” is often employed. Often, a multidisciplinary team is used, which may include primary care physicians [15], nurses [12], dietitians, psychologists, or exercise physiologists. For example, in Patel’s review of motivational interviewing interventions for weight loss [16], the providers were most often classified as “lifestyle coaches,” and also included dieticians, psychologists, and medical assistants. Given the reliance upon technology, IT staff capable of providing technical support may be welcome additions, although few interventions specifically mention them. The background of providers may be less important than their ability to form a positive, supportive relationship with participants. Krukowski et al. [18] found that during an 18-month weight loss program delivered via online group chats, the quality of patient-provider bond was significantly associated with weight loss at 6 months (p = 0.03) but not at 18 months (p = 0.53). Patient-provider bond at 6 months predicted program attendance at 6 months (b = 0.63, p = 0.04), and 6-month attendance predicted weight loss at 6 months (b = −0.594, p < 0.001), even though the total weight loss explained was small (0.04 kg).

While less common, a few telemedicine interventions utilize a peer group format, allowing trained peer facilitators to lead group education and discussion sections [18]. Peer support groups for weight loss have a number of advantages, including providing social support for isolated members, increased credibility of peer facilitators who are seen as “part of the group,” and fostering a sense of community among members [19]. This may be especially important for subpopulations who do not receive social support for weight loss among their family and friends. For example, men have rates of obesity comparable to those of women [20], but only 27% of weight loss study participants are male, and only 4% of weight loss trials are all male. Men tend to view activities such as dieting as feminine and perceive little social support for weight loss from their male friends [19]. During interviews about social support for weight loss with men who had previously undergone weight loss surgery, many reported feeling a stigma to seeking weight loss counseling, as well as isolation during overwhelmingly female weight loss support groups [21]. Many men expressed a positive experience with online social support, including online support groups and social media, suggesting that telemedicine may be an acceptable option as a weight loss experience tailored to their needs.

Technology and Digital Health Skills

Videoconferencing is an especially promising form of telemedicine, defined as telecommunication technology which allows for two-way, real-time audio and visual communication. Videoconferencing has become more common in nonclinical areas, such as education and business, and will likely remain so. Videoconferencing offers many of the advantages of in-person programs, including face-to-face interactions and the possibility of providers giving visual demonstrations, while maintaining the practical and safety advantages of remote interventions. During interviews following a 6-month group-based videoconferencing intervention, participants reported that videoconferencing “exceeded my expectations,” and expressed appreciation for the lack of required travel, saved time and money, and fewer disruptions to their workday, as well as “reduced threat,” to be attending a group session in their own homes [22•]. Participants also reported perceived social support from their fellow group members. Almost all participants reported technical difficulty, ranging from difficulty installing the videoconferencing app (Skype Business) to unreliable Internet connections, equipment incompatibility, etc. Participants felt most comfortable if they had prior experience with videoconferencing. One participant withdrew due to lack of bandwidth. A test call prior to study implementation was helpful in troubleshooting. Participants considered the technical issues to be “annoying” and “distracting” but not detrimental to the overall experience. These results highlight the need for participants to have digital literacy skills, as well as access to affordable, reliable Internet service.

Because videoconferencing is a relatively new technology, it has been less frequently studied than older technologies such as telephone and Web-chat interventions. Patel et al.’s review [16] of remote motivational interviewing interventions found that 80% used telephones, 13% email and phone, and 7% synchronous online chats, with none utilizing videoconferencing. Programs will often utilize multiple modalities, such as text messages and videoconferencing, within the same intervention. A different review from 2019 found the most common modality was mobile phones (48%), followed by telephone and videoconferencing (22% ), eHealth (26%), and wearable devices [10•]. Mobile phone interventions were more likely to show statistically significant results than those using telephone/telemedicine or EHealth. User’s prior experience with the needed technology and technology usability tended to be critical factors in intervention success [10•]. Future reviews are needed to definitively compare the effectiveness of developing technologies.

Efficacy of Telemedicine Interventions

The second essential question to answer is: are the health outcomes of telemedicine appointments on par with what could be achieved in an in-person format? Overall results suggest telemedicine interventions can lead to clinically meaningful weight loss. For example, West et al. [13] compared the efficacy and feasibility of a group-based weight loss intervention based upon a manualized in-person intervention. Women with obesity were randomized to either an hour-long synchronous text-based group chat or videoconference group discussion. Greater attrition was observed in the text-based group (31%) compared to the videoconferencing group (12%). The videoconferencing group lost more weight (−5.0% ± 6.0% body weight) compared to the text-based group (−3.0% ± 4.1%). Both results were not significant, possibly due to the small sample size (N = 24 completed the study). The authors note a moderate effect size of 0.4, which would have been statistically significant with N = 100 (see Table 1).

Das et al. [23] studied iDiet®, a commercial weight loss program. Participants chose an in-person (25%) or videoconferencing intervention (75%). Fifty-eight percent of those who began the program achieved a 5% weight reduction. Study completers lost a mean of 7.4% ± 3.6% body weight. Seventy-four percent of completers achieved at least 5% weight loss, although the authors do not state if this was statistically significant. Greater weight loss was achieved by those who enrolled in January–March (p = 0.022), older than 30 years old (2.2% difference; p = 0.013), and worksite participants (1.2 % difference; p = 0.001). Virtual participants, older participants, and those in incentivized programs were more likely to complete the program (p < 0.004). Program success was not impacted by gender, starting BMI, or videoconference vs in-person format. The reason for the videoconferencing format’s greater popularity was not given. Because participants chose their preferred format, a greater number of participants may have chosen videoconferencing because they found the format more enjoyable or more convenient, or had prior experience with the technology. Given the comparative popularity of the videoconferencing format, the greater completion rate of that program, and the potential for widespread dissemination, the equivalent videoconferencing vs in-person weight loss results are even more encouraging (see Table 1).

Another example is Johnson et al. [24]. Sedentary adults (N = 30) were randomized to either a videoconferencing, in-person, or control condition. Participants in the two active conditions received personalized feedback from a multidisciplinary team of health coaches, including dieticians, exercise physiologists, and a medical doctor. The videoconferencing group showed greater weight loss (8.23 kg ± 4.5 kg; 7.7% body weight) compared to the in-person group (3.2 kg ± 2.6 kg; 3.4% body weight) and control (2.9 kg ± 3.9 kg; 3.3% body weight) (p < 0.05), as well as greater daily steps (p = 0.03). Changes in blood glucose, insulin, and HbA1C were not significantly different across interventions. The authors suggest that the videoconferencing intervention showed results superior to the in-person module because the virtual format showed better attendance (100%) compared to the in-person format (80% attendance) (see Table 1).

Alencar et al. [15] combined videoconferencing with activity trackers in an intervention designed to promote 1–2 pounds of weight loss per week. Participants were given a digital scale for weekly weight monitoring, an activity tracker for daily activity monitoring, and content from the Telemedicine Enabled Approach to Multidisciplinary care (TEAM™) intervention. Participants were randomized to regular videoconferencing coaching or to a control group that received the devices but did not receive feedback. The videoconferencing group showed greater adherence to both the scale (92% ± 0.10% vs. 75% ± 15%, p < 0.05) and tracker (80% ± 0.14% vs. 49% ± 15%, p < 0.05), and a greater rate of weekly weight loss (mean −0.74 ± SD 1.8 kg) compared to the control group (p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Ventura et al. conducted a telenutrition study for 40–70-year-old men. Control participants received usual care; telenutrition participants also received weekly videoconferencing or telephone health coaching sessions. Both groups showed improvements in weight loss, body fat percentage, waist circumference, overall diet quality, and calorie intake (p < 0.001) [25]. The telenutrition participants were more likely to lose 5% of body weight (70.4%) compared to usual care (41.4%) (p = 0.035) (Table 1). In general, telemedicine interventions are associated with results comparable to other formats, but studies have been usually very small.

Telemedicine in Bariatric Patients

Bariatric surgery is one of the most successful weight loss treatments. Many patients regain weight following surgery or do not achieve their targeted weight loss goals [26]. Lifestyle interventions help maintain the loss but only 40% of patients returning for their four annual in-person follow-up visits [27]. A review of telemedicine following bariatric surgery [28] found that 90% showed positive outcomes in weight loss and nutrition knowledge, as well as a high level of satisfaction. Most were small feasibility studies. Seventy percent used telephone modality. For example, Bradley et al. converted an in-person intervention to an online format supplemented with telephone coaching. Participants were bariatric surgery patients who had regained at least 10% of their body weight since their lowest postsurgery weight [17]. Those who completed treatment lost a significant amount of weight at program’s end (5.1% ± 5.5% body weight; 5.9 kg ± 6.5 kg, p = 0.01), and a small amount of additional weight at 3 months’ follow-up (0.6 ± 2.7% body weight). However, only 18% of potentially interested participants enrolled and just over half of enrollees completed the study (N = 20 enrolled; N = 11 completed).

Weight Loss for Obesity-Derived Comorbidities

Weight loss is desirable among patients with obesity-associated illnesses such as diabetes or heart disease. An example of a successful weight control intervention for diabetes is the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), a lifestyle-based intervention with an impressive 58% success rate in reducing incidence of diabetes [29] and effects lasting 10 years [30]. A review and meta-analysis by Joiner et al. [31] examined the success of converting DPP to telehealth or eHealth format. Behavioral support was offered remotely via a variety of modalities including videoconferencing, email, online messaging, telephone, and a mix of telephone and online messaging. The DPP content was usually delivered via a Web-based app. Meta-analysis results found DPP with on-going behavioral support resulted in greater mean percentage weight change than a standalone DPP content without support, regardless of whether that support was delivered virtually (−4.31%, 95% CI −5.26 to −3.37%, I2= 78.4%) or in-person (−4.65%, 95% CI −6.63 to −2.67%, I2= 94.5%). The authors note considerable heterogeneity in modalities used. Future research is needed to determine the optimal method. Even when not specifically targeted, telemedicine weight management interventions can positively impact metabolic markers of diabetes. Johnson et al. [24] describe a weight loss intervention in which the videoconferencing arm showed a significant improvement in insulin sensitivity, as well as greater weight loss compared to controls.

Weight loss has been observed in a variety of patients enrolled in the DPP. In one study, for example, rural-dwelling cardiac rehabilitation patients were randomized to a 12-week telehealth cardiac rehabilitation program with additional weight management components or to receive only the cardiac rehabilitation program. Participants were provided with skill-building education sessions based upon the DPP, along with telehealth coaching sessions delivered by a research nurse at weeks 9 and 12. The weight management group lost significantly more weight (13.8 pounds, or an average of 5.9% total body weight), compared to the control group (p < 0.05). At 6 months, the weight management group spent almost twice as much time in moderate to vigorous physical activity (24 min/day) compared to the control group (14 min/day), although this difference was not significant. Patients in the weight management group showed greater patient activation in managing their own healthcare (p = 0.02), and were more likely to use weight management strategies including planning diet, monitoring diet, buying food, preparing food, and portion control [12•].

Future Research

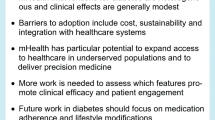

Telemedicine may be especially useful when it allows greater healthcare access among underserved or high-risk populations, such as the elderly population. Senior citizens account for a growing percentage of the population, and many have obesity as well as obesity-related comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes, or arthritis. Despite this, few studies have examined telemedicine weight loss interventions for seniors [32], an important research gap.

Telemedicine has been described as especially useful for expanding healthcare access in rural communities, by eliminating a lengthy commute and providing access to specialists local communities lack [32]. Unfortunately, many rural communities lack access to reliable, affordable Internet. A related difficulty is the link between digital literacy skills, such as familiarity with videoconferencing, and intervention success. Future interventions may wish to combine health-related content with technical skills training or close contact with community organizations providing low-cost Internet access.

One serious limitation of the reviewed studies is sample size and generalizability. Most studies reviewed were feasibility studies, with small sample sizes (i.e., Bradley et al., N = 20 enrolled, N = 11 completed study) [17], often further divided into two or more randomized groups. Therefore, generalizability of study results is questionable at best. Alencar et al. [15], excluded participants with both type I and type II diabetes, and “receiving treatment for a serious medical condition (i.e., cancer).” While understandable in a small-scale feasibility study, such criteria severely limit the interventions’ usefulness in the general population, a large percentage of whom seek weight loss to improve obesity-associated health conditions. As previously noted, women are overrepresented in weight loss interventions, especially younger, Caucasian women. Expansion of telemedicine to men, ethnic minorities, and older adults is needed.

The ease of access of telemedicine should make longer-term interventions possible. Despite this, most interventions do not exceed a 10–12-week duration. Because studies of longer interventions show superior results and may help prevent weight regain, future studies should examine longer durations. Greater consideration should also be given to developing technologies, especially videoconferencing and remote monitoring devices, such as activity trackers, scales, and apps. Interventions utilizing weight loss as a treatment for obesity-derived illnesses may wish to incorporate remote monitoring of illness markers, such as at-home blood pressure monitoring or daily blood glucose testing.

Conclusion

In summary, telemedicine represents a promising modality with great potential to deliver much-needed weight loss interventions. Accumulating evidence demonstrates meaningful clinical improvements in body weight, physical activity, and nutrition. Several critical research and practice gaps remain, including optimal modality and duration and usefulness in special populations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Lin AL, Vittinghoff E, Olgin JE, Pletcher MJ, Marcus GM. Body weight changes during pandemic-related shelter-in-place in a longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e212536–e.

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Overweight & obesity statistics: [Available from: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/overweight-obesity.

Calton B, Abedini N, Fratkin M. Telemedicine in the time of coronavirus. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2020.

• Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Changes to telehealth policy, delivery, and outcomes in response to COVID-19 2020 [March 30, 2021]. Available from: https://www.pcori.org/document/changes-telehealth-policy-delivery-and-outcomes-response-covid-19-landscape-review. This document provides details of changes in telemedicine brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, including context, policy changes, trends in usage, etc.

Dryrda L. Telehealth may see big long-term gains due to COVID-19: 10 observations: Becker ' s Hospital Review; April 17, 2020 [Available from: https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/telehealth/telehealth-may-see-big-long-term-gains-due-to-covid-19-10-observations.html.

Bajowala SS, Milosch J, Bansal C. Telemedicine pays: billing and coding update. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020;20(10):1–9.

Guido-Estrada N, Crawford J. Embracing telemedicine: the silver lining of a pandemic. Pediatr Neurol. 2020.

Almathami HKY, Win KT, Vlahu-Gjorgievska E. Barriers and facilitators that influence telemedicine-based, real-time, online consultation at patients’ homes: systematic literature review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(2):e16407.

Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. Telemedicine 2020 and the next decade. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):859.

• Houser SH, Joseph R, Puro N, Burke DE. Use of technology in the management of obesity: a literature review. Perspectives In Health Information Management. 2019;16(Fall) This review details telemedicine interventions from 2010 to 2017. While somewhat dated, it includes useful definitions and details about various telemedicine modalities.

Sorgente A, Pietrabissa G, Manzoni GM, Re F, Simpson S, Perona S, et al. Web-based interventions for weight loss or weight loss maintenance in overweight and obese people: a systematic review of systematic reviews. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(6):e229.

• Barnason S, Zimmerman L, Schulz P, Pullen C, Schuelke S. Weight management telehealth intervention for overweight and obese rural cardiac rehabilitation participants: a randomised trial. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(9-10):1808–18 This RCT measured not only weight loss outcomes but also process goals, including self-efficacy for diet and exercise, patient activation, and various dietary strategies, providing insight into cognitive changes necessary for weight loss.

West DS, Stansbury M, Krukowski R, Harvey J. Enhancing group-based internet obesity treatment: a pilot RCT comparing video and text-based chat. Obes Sci Pract. 2019;5(6):513–20.

Statistica Research Department. U.S. Diets and weight loss -- statistics and facts 2020 [Available from: https://www.statista.com/topics/4392/diets-and-weight-loss-in-the-us/.

Alencar M, Johnson K, Gray V, Mullur R, Gutierrez E, Dionico P. Telehealth-based health coaching increases m-health device adherence and rate of weight loss in obese participants. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2020;26(3):365–8.

Patel ML, Wakayama LN, Bass MB, Breland JY. Motivational interviewing in eHealth and telehealth interventions for weight loss: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2019;126:105738.

Bradley LE, Forman EM, Kerrigan SG, Goldstein SP, Butryn ML, Thomas JG, et al. Project HELP: a remotely delivered behavioral intervention for weight regain after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2017;27(3):586–98.

Krukowski RA, West DS, Priest J, Ashikaga T, Naud S, Harvey JR. The impact of the interventionist–participant relationship on treatment adherence and weight loss. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(2):368–72.

Ufholz K. Peer support groups for weight loss. Current Cardiovascular Risk Reports. 2020;14(10):1–11.

Pagoto SL, Schneider KL, Oleski JL, Luciani JM, Bodenlos JS, Whited MC. Male inclusion in randomized controlled trials of lifestyle weight loss interventions. Obesity. 2012;20(6):1234–9.

Moore DD, Willis ME. Men’s experiences and perspectives regarding social support after weight loss surgery. Journal of Mens Health. 2017;12(2).

• Cliffe M, Di Battista E, Bishop S. Can you see me? Participant experience of accessing a weight management programme via group videoconference to overcome barriers to engagement. Health Expect. 2021;24(1):66–76 Qualitative interviews from participants in weight loss support group detail aspects of telemedicine that participants found helpful and provide valuable patient perspectives.

Das SK, Brown C, Urban LE, O ' Toole J, Gamache MMG, Weerasekara YK, et al. Weight loss in videoconference and in-person iDiet weight loss programs in worksites and community groups. Obesity. 2017;25(6):1033–41.

Johnson KE, Alencar MK, Coakley KE, Swift DL, Cole NH, Mermier CM, et al. Telemedicine-based health coaching is effective for inducing weight loss and improving metabolic markers. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2019;25(2):85–92.

Ventura Marra M, Lilly CL, Nelson KR, Woofter DR, Malone J. A pilot randomized controlled trial of a telenutrition weight loss intervention in middle-aged and older men with multiple risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Nutrients. 2019;11(2):229.

Courcoulas AP, Christian NJ, Belle SH, Berk PD, Flum DR, Garcia L, et al. Weight change and health outcomes at 3 years after bariatric surgery among individuals with severe obesity. Jama. 2013;310(22):2416–25.

Gould JC, Beverstein G, Reinhardt S, Garren MJ. Impact of routine and long-term follow-up on weight loss after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3(6):627–30.

Coldebella B, Armfield NR, Bambling M, Hansen J, Edirippulige S. The use of telemedicine for delivering healthcare to bariatric surgery patients: a literature review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(10):651–60.

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393–403.

Group DPPR. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet. 2009;374(9702):1677–86.

Joiner KL, Nam S, Whittemore R. Lifestyle interventions based on the diabetes prevention program delivered via eHealth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2017;100:194–207.

Batsis JA, Pletcher SN, Stahl JE. Telemedicine and primary care obesity management in rural areas–innovative approach for older adults? BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):1–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Kelsey Ufholz and Daksh Bhargava declare they have no conflicts of interest to declare, including financial conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Obesity and Diet

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ufholz, K., Bhargava, D. A Review of Telemedicine Interventions for Weight Loss. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep 15, 17 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12170-021-00680-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12170-021-00680-w