Abstract

While recent research has shown a growing interest in the consequences of China’s foreign aid giving, few have examined how public attitudes towards China in recipient countries have responded to the surging inflows of Chinese aid. Using a geo-referenced dataset combining individual survey data with foreign aid project sites information, this paper examines the association between Chinese aid projects and public approval of China’s influence in African countries. Despite contributing to development and growth in recipient countries, Chinese aid inflows may have a bifurcating effect on the approval of the donor along a partisan line. In the African context of neopatrimonialism and patronage politics, Chinese foreign aid packages are likely manipulated by the recipient government to further its domestic political interests, which could result in a partisan bias in the distribution of aid benefits favoring supporters of the incumbent government. As a result, the local presence of Chinese aid sites would be more strongly associated with a favorable attitude towards China among supporters of the incumbent political party than supporters of the opposition. We find support for our argument from a multilevel modeling of the association between the approval of China among individuals and the presence of nearby Chinese aid projects sites between 2009 and 2014.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Depending on the location of the respondents, we retain projects launched between 2009 and 2013 if the survey at the respondent’s location was administered in 2014, and those started between 2010 and 2014 if it was implemented in 2015. As a robustness check (Table A1), we adopt alternative time spans of projects by the year commenced when counting adjacent sites (i.e., 2007, 2008, 2010, and 2011). Following Isaksson and Kotsadam (2018), we retain aid projects with a location precision level of 1 or 2.

Several countries in Round 6 of the Afrobarometer were excluded either because they did not receive Chinese ODA-type aid with precise location information during the sample period (Burkina Faso, São Tomé and Príncipe, and South Africa) or due to a lack of information in the country survey that records partisan winner or loser status (Egypt, Lesotho, and Morocco).

While Ethiopia constitutes a good case for examining the attitudinal impact of Chinese aid inflows, excluding it is unlikely to substantially bias the representativeness of our sample provided that the majority of the biggest recipients are covered.

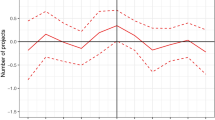

Favorability of China among those who do not live near Chinese aid sites is 78.3% among partisan winners and 74.6% among losers. When there are more than four Chinese aid sites nearby, the average favorability of China increases to 79.2% among winners and decreases to 69.5% among losers.

The nighttime luminosity data is collected from the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program’s Operational Linescan System (DMSP-OLS), provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Regional population size is calculated using the Global Administrative Areas Database.

The inter-class correlation coefficients for the second and third levels are 13.56 and 17.42, respectively, meaning that approximately 13.56% of the variation is accounted for by the country level and 17.42% of the variation is explained by the region and country levels. This provides another justification for using a multilevel model.

Unfortunately, there is no comparable question directly capturing approval of the World Bank’s influence. We instead use a question asking whether respondents perceive “international organizations like the United Nations or the World Bank” as the most influential in their country. Nor is there a comparable question on approval of the USA. We therefore use a question asking whether respondents recognize the “United States” has the most influence in their country.

This can be seen in the insignificant interaction term and in Appendix Figure A1.

Isaksson and Kotsadam (2018) dealt with endogeneity concerns using a difference-in-difference (DID) method comparing cases of active vs. planned Chinese aid sites. Unfortunately, we cannot use a similar approach given that questions regarding China and Chinese aid were only asked in Round 6 of the Afrobarometer in 2014 and 2015.

We use the closest seaport of neighboring countries if respondents are from inland countries.

The correlation between distance to port (log) and number of aid sites is −0.279, and the correlation between latitude and number of aid sites is −0.121. The F-statistics for the excluded instrument clearly adhere to the “rule of thumb” that it should be at least 10 (10.18 for the number of Chinese aid sites and 15.27 for the interaction term) (Staiger and Stock 1997). Also, overidentification statistic for the Sargan-Hansen test is 3.574 (p = 0.1674), indicating that these are valid instruments.

References

Aidoo R, Hess S. Non-interference 2.0: China’s evolving foreign policy towards a changing Africa. J Curr Chin Aff. 2015;44(1):107–39.

Alesina A, Michalopoulos S, Papaioannou E. Ethnic inequality. J Polit Econ. 2016;124(2):428–88.

Bailey MA, Strezhnev A, Voeten E. Estimating dynamic state preferences from United Nations voting data. J Confl Resolut. 2017;61(2):430–56.

Bleaney M, Dimico, A. Biogeographical conditions, the transition to agriculture and long-run growth. Eur Econ Rev. 2011;55(7):943–54.

Bratton M, Chang ECC. State building and democratization in Africa: forwards, backwards or together? Comp Political Stud. 2006;39(9):1059–83.

Bräutigam D. The dragon’s gift: the real story of China in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010.

Bräutigam D. Aid with Chinese characteristics’: Chinese foreign aid and development finance meet the OECD-DAC aid regime. J Int Dev. 2011;23:752–64.

Castells-Quintana D, Larrú JM. Does aid reduce inequality? Evidence for Latin America. Eur J Dev Res. 2015;27(5):826–49.

Cooray A, Dzumashev R, Schneider F. How does corruption affect public debt? An empirical analysis World Dev. 2017;90:115–27.

Coppedge M, Gerring J, Knutsen CH, Lindberg SI, Teorell J, Altman D, Bernhard M, Fish MS, Glynn A, Hicken A, Luhrmann A, Marquardt KL, McMann K, Paxton P, Pemstein D, Seim B, Sigman R, Skaaning SE, Staton J, Wilson S, Cornell A, Alizada N, Gastaldi L, Gjerløw H, Hindle G, Ilchenko N, Maxwell L, Mechkova V, Medzihorsky J, von Römer J, Sundström A, Tzelgov E, Wang Y, Wig T, Ziblatt D V-Dem [Country–Year/Country–Date] Dataset v10. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project, 2020. https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds20

Davie P. China and the end of poverty in Africa—towards mutual benefit?, Sundyberg, Sweden: Alfaprint; 2007.

Devarajan S, Swaroop V. The implications of foreign aid fungibility for development assistance. In: Gilbert CL, Vines D, editors. The World Bank: structure and policies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

Dreher A, Fuchs A. Rogue aid? An empirical analysis of China’s aid allocation. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d’économique. 2015;48(3):988–1023.

Dreher A, Fuchs A, Parks B, Strange AM, Tierney MJ (2017) Aid, China, and growth: evidence from a new global development finance dataset. AIDDATA Working Paper 46.

Dreher A, Fuchs A, Hodler R, Parks B, Raschky PA, Tierney MJ. African leaders and the geography of China’s foreign assistance. J Dev Econ. 2019;140:44–71.

Faria HJ, Montesinos HM. Does economic freedom cause prosperity? An IV Approach. Public Choice. 2009;141(1-2):103–27.

Fuchs, A, Rudyak M (2019) The motives of China’s foreign aid. In Handbook on the international political economy of China. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Gonzalez-Vicente R. The political economy of Sino-Peruvian relations: a new dependency? J Curr Chin Aff. 2012;41(1):97–131.

Henderson JV, Storeygard A, Weil DN. Measuring economic growth from outer space. Am Econ Rev. 2012;102(2):994–1028.

Herzer D, Nunnenkamp P. The effect of foreign aid on income inequality: evidence from panel cointegration. Struct Change Econ Dynamics. 2012;23(3):245–55.

Hodler R, Raschky P (2010) Foreign aid and enlightened leaders. Monash Economics Working Papers 54-10, Monash University, Department of Economics.

Isaksson A-S, Kotsadam A. Chinese aid and local corruption. J Public Econ. 2018;159:146–59.

Jablonski RS. How aid targets votes: the impact of electoral incentives on foreign aid distribution. World Polit. 2014;66(2):293–330.

Lekorwe M, Chingwete A, Okuru M, Samson R (2016) China’s growing presence in Africa wins largely positive popular reviews. Afrobarometer Dispatch 122.

Lengauer S. China’s foreign aid policy: motive and method. Cult Mandala: Bull Centre East-West Cult Econ Stud. 2011;9(2):35–8181.

Mansfield E, Mutz DC, Silver LR. Men, women, trade, and free markets. Int Stud Q. 2015;59(2):303–15.

McDonald K, Bosshard P, Brewer N. Exporting dams: China’s hydropower industry goes global. J Environ Manage. 2009;90:294–302.

Moehler D. Critical citizens and submissive subjects: elections losers and winners in Africa. Br J Polit Sci. 2009;39(2):345–66.

Moehler D, Lindberg SI. Narrowing the legitimacy gap: turnovers as a cause of democratic consolidation. J Polit. 2009;71(4):1448–66.

Moyo D. Dead aid: why aid is not working and how there is a better way for Africa. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2009.

Naìm M. Rogue aid. Foreign Policy. 2007;159:95–6.

Pack H, Pack JR. Is foreign aid fungible? The case of Indonesia. Econ J. 1990;100(3):188–94.

Remmer KL. Does foreign aid promote the expansion of government? Am J Polit Sci. 2004;48(1):77–92.

Samy Y. China’s aid policies in Africa: opportunities and challenges. The Round Table. 2010;99(2):75–90.

Sokolov B, Inglehart R, Ponarin E, Vartanova I, Zimmerman W. Disillusionment and anti-Americanism in Russia: from pro-American to anti-American attitudes, 1993-2009. Int Stud Q. 2018;62(2):534–47.

Spencer NH, Fielding A. An instrumental variable consistent estimation procedure to overcome the problem of endogenous variables in multilevel models. Multilevel Modelling Newsletter. 2000;12:4–7.

Staiger D, Stock JH. Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica. 1997;65(3):557–86.

Stallings B. Chinese foreign aid to Latin America: trying to win friends and influence people. In: Myers M, Wise C, editors. The political economy of China-Latin America relations in the new millennium: brave new world. New York: Routledge; 2017. p. 69–91.

State Council (2014) White paper on China’s foreign aid, Information Office of the State Council, The People’s Republic of China, July 2014, Beijing.

Steenbergen MR, Jones BS. Modeling multilevel data structures. Am J Polit Sci. 2002;46(1):218–37.

Suzuki S. Chinese soft power, insecurity studies, myopia and fantasy. Third World Q. 2009;30(4):779–93.

Svensson J. Eight questions about corruption. J Econ Perspect. 2005;19(3):19–42.

Tangri RK. The politics of patronage in Africa: parastatals, privatization, and private enterprise. Trenton: Africa World Press; 1999.

Taylor I. China’s foreign policy towards Africa in the 1990s. J Mod Afr Stud. 1998;36(3):443–60.

Tierney MJ, Nielson DL, Hawkins DG, Timmons Roberts J, Findley MG, Powers RM, et al. More dollars than sense: refining our knowledge of development finance using AidData. World Dev. 2011;39(11):1891–906.

Tull DM. China’s engagement in Africa: scope, significance and consequences. J Mod Afr Stud. 2006;44(3):459–79.

Van de Walle, N. African economies and the politics of permanent crisis, 1979-1999: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

Wang Y. Public diplomacy and the rise of Chinese soft power. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci. 2008;616(1):257–73.

Weidmann NB, Schutte S. Using night light emissions for the prediction of local wealth. J Peace Res. 2017;54(2):125–40.

Western B. Causal heterogeneity in comparative research: a Bayesian hierarchical modeling approach. Am J Polit Sci. 1998;42(4):1233–59.

Wooldridge J. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2002.

Acknowledgements

We thank Xun Cao, Zhenqian Huang, Xun Pang, Mi Jeong Shin, Dan Slater, Fangjin Ye, Suisheng Zhao, and the two anonymous referees for valuable comments on the paper. Jia Chen acknowledges the funding support from the National Foundation for Social Sciences (No. 17CGJ032). Sung Min Han acknowledges that this work was supported by Hankuk University of Foreign Studies Research Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jia Chen and Sung Min Han contributed to the research and writing of the article equally.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, J., Han, S. Does Foreign Aid Bifurcate Donor Approval?: Patronage Politics, Winner–Loser Status, and Public Attitudes toward the Donor. St Comp Int Dev 56, 536–559 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-021-09341-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-021-09341-w