Abstract

The future development of population size and structure is of importance since planning in many areas of politics and business is conducted based on expectations about the future makeup of the population. Countries with both decreasing mortality and low fertility rates, which is the case for most countries in Europe, urgently need adequate population forecasts to identify future problems regarding social security systems as one determinant of overall macroeconomic development. This contribution proposes a stochastic cohort-component model that uses simulation techniques based on stochastic models for fertility, migration and mortality to forecast the population by age and sex. We specifically focused on quantifying the uncertainty of future development as previous studies have tended to underestimate future risk.

The model is applied to forecast the population of Germany until 2045. The results provide detailed insight into the future population structure, disaggregated into both sexes and age groups. Moreover, the uncertainty in the forecast is quantified as prediction intervals for each subgroup.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For further reading on the distinction between forecasts and projections, see, e.g., Bohk (2012: 21–25).

The mean age at childbirth in 2015 was 31, and long-term increases were nearly linear per annum for almost two decades (see GENESIS-Online Datenbank 2018).

The original sources serve as a more detailed description of the models and their results.

Our dataset does not exist as such but is rather estimated from different sources used by Vanella and Deschermeier (2018) in their study. Therefore, we call it a synthetic dataset.

The exact method for deriving the synthetic data is outlined in Vanella and Deschermeier (2018: 264–271).

Dividing the population into migrants and natives may be of interest for many research questions, such as for the labor market. However, the population data for Germany by nationality are of too low quality and the corresponding time series are too short to derive representative base data on this issue.

A mortality rate for a particular year is generally calculated by dividing the number of deaths that occurred during that year by the number of persons at risk of dying in that same cohort who are still alive at the end of the previous year.

The authors propose, based on the historical data and further considerations, 1/6 as the upper bound for the ASFRs (Vanella and Deschermeier 2019: 89).

Note that, since our definition of mortality and survival rates strictly restricts them to the interval [0; 1], mx, y, g, t + sx, y, g, t = 1 ∀ x, y, g, t.

Our model predicts a slight increase in the median TFR from its initial value of 1.56 in 2016 to 1.67 in 2045.

More detailed results, although based on the jump-off year 2015, can be found in Vanella and Deschermeier (2018: 274–276).

References

Alho, J. M., & Spencer, B. D. (2005). Statistical demography and forecasting. New York: Springer Science+Business Media.

Alkema, L., Raftery, A. E., Gerland, P., Clark, S. J., Pelletier, F., Büttner, T., & Heilig, G. K. (2011). Probabilistic projections of the Total fertility rate for all countries. Demography, 48(3), 815–839.

Aust, S., Bewarder, M., Büscher, W., Lutz, M., & Malzahn, C.C. (2015). Herbst der Kanzlerin. Geschichte eines Staatsversagens. [Autumn of the chancellor. History of a state failure.] Welt. https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article148588383/Herbst-der-Kanzlerin-Geschichte-eines-Staatsversagens.html. Accessed 5 Mar 2019.

Azose, J. J., & Raftery, A. E. (2015). Bayesian probabilistic projection of international migration. Demography, 52(5), 1627–1650.

Azose, J. J., Ševčíková, H., & Raftery, A. E. (2016). Probabilistic population projections with migration uncertainty. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(23), 6460–6465.

Bell, W. R., & Monsell, B. (1991). Using principal components in time series modeling and forecasting of age-specific mortality rates. In American Statistical Association (Ed.), Proceedings of the social statistics section (pp. 154–159). Alexandria: American Statistical Association.

Bewarder, M., & Leubecher, M. (2016). Syrische Staatsbürgerschaft wird massenhaft vorgetäuscht. [Syrian citizenship is faked massively.] Welt. https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article156496638/Syrische-Staatsbuergerschaft-wird-massenhaft-vorgetaeuscht.html. Accessed 5 Mar 2019.

Bohk, C. (2012). Ein probabilistisches Bevölkerungsprognosemodell: Entwicklung und Anwendung für Deutschland [A probabilistic population forecast model: Development and Application for Germany.]. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Bomsdorf, E., Babel, B., & Schmidt, R. (2008). Zur Entwicklung der Bevölkerung, der Anzahl der Schüler, der Studienanfänger und der Pflegebedürftigen: Stochastische Modellrechnungen für Deutschland bis 2050. [Development of population, number of students, newly enrolled and people in need of care: Stochastic simulations for Germany until 2050.]. Sozialer Fortschritt (German Review of Social Policy), 57(5), 125–132.

Booth, H. (2006). Demographic forecasting: 1980 to 2005 in review. International Journal of Forecasting, 22(3), 547–581.

Booth, H., Hyndman, R. J., Tickle, L., & de Jong, P. (2006). Lee-Carter mortality forecasting: A multi-country comparison of variants and extensions. Demographic Research, 15(9), 289–310.

Box, G. E. P., Jenkins, G. M., Reinsel, G. C., & Ljung, G. M. (2016). Time series analysis. Forecasting and control. Hoboken: Wiley.

Bozik, J. E., & Bell, W. R. (1987). Forecasting age specific fertility using principal components (SRD Research Report Number CENSUS/SRD/RR-87/19). Retrieved from the Bureau of the Census, Statistical Research Division website: https://www.census.gov/srd/papers/pdf/rr87-19.pdf. Accessed 29 Nov 2018.

Brücker, H., Hauptmann, A., & Sirries, S. (2017a). Zuzüge nach Deutschland. [Immigration into Germany.] Retrieved from the Institut für Arbeitsmarkt und Berufsforschung website: http://doku.iab.de/aktuell/2017/aktueller_bericht_1701.pdf. Accessed 29 Nov 2018.

Brücker, H., Hauptmann, A., & Sirries, S. (2017b). Arbeitsmarktintegration von Geflüchteten in Deutschland: Der stand zum Jahresbeginn 2017. [Labor market integration of refugees in Germany: The state at the beginning of the year 2017.] Retrieved from the Institut für Arbeitsmarkt und Berufsforschung website: http://doku.iab.de/aktuell/2017/aktueller_bericht_1704.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2018.

Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge. (2016). Das Bundesamt in Zahlen 2015: Asyl, Migration und Integration. [The Federal Office in Numbers 2015: Asylum, Migration and Integration.] Retrieved from the BAMF website: https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Publikationen/Broschueren/bundesamt-in-zahlen-2015.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. Accessed 17 May 2018.

Bundesministerium des Innern. (2011). Migrationsbericht 2009. [Migration Report 2009.] Retrieved from the BAMF website: https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Publikationen/Migrationsberichte/migrationsbericht-2009.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. Accessed 5 Mar 2019.

Cannan, E. (1895). The probability of a cessation of the growth of population in England and Wales during the next century. The Economic Journal, 5(20), 505–515.

Census Bureau of England and Wales (1863). General report; with appendix of tables. Retrieved from the A vision of Britain through Time website: http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/census/EW1861GEN/5. Accessed 5 Mar 2019.

Council on Foreign Relations. (2012). Islamist extremism after the Arab spring. Interview by Jonathan Masters with Ali Soufan. https://www.cfr.org/interview/islamist-extremism-after-arab-spring. Accessed 5 Mar 2019.

Davis, D. L., Webster, P., Stainthorpe, H., Chilton, J., Jones, L., & Doi, R. (2007). Declines in sex ratio at birth and fetal deaths in Japan, and in U.S. whites but not African Americans. Environmental Health Perspectives, 115(6), 941–946.

Deschermeier, P. (2011). Die Bevölkerungsentwicklung der Metropolregion Rhein-Neckar: Eine stochastische Bevölkerungsprognose auf Basis des Paradigmas funktionaler Daten. [Population Development of the Rhine-Neckar Metropolitan Area: A Stochastic Population Forecast on the Basis of Functional Data Analysis.]. Comparative Population Studies, 36(4), 769–806.

Deschermeier, P. (2015). Die Entwicklung der Bevölkerung Deutschlands bis 2030 – ein Methodenvergleich. [Population Development in Germany to 2030: A Comparison of Methods.]. IW Trends – Vierteljahresschrift zur empirischen Wirtschaftsforschung, 42(2), 97–111.

Deschermeier, P. (2016). Einfluss der Zuwanderung auf die demografische Entwicklung in Deutschland. [The Influence of Immigration on Demographic Developments in Germany.]. IW Trends – Vierteljahresschrift zur empirischen Wirtschaftsforschung, 43(2), 21–38.

Destatis. (2007). Lebendgeborene nach dem Alter der Mutter 1990: Neue Länder und Berlin-Ost. [Live Births by Mother’s Age 1990: New Federal States and Eastern Berlin.] Data provided on 13 Feb 2018.

Destatis. (2009). Bevölkerung Deutschlands bis 2060. Ergebnisse der 12. koordinierten Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung. [Germany’s Population by 2060: Results of the 12th coordinated population projection.] Retrieved from the Destatis website: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Bevoelkerungsvorausberechnung/_inhalt.html#sprg233474. Accessed 12 Nov 2019.

Destatis. (2014a). Lebendgeborene nach dem Alter der Mütter 1968–1990: Alte Bundesländer. [Live Births by Mothers’ Age 1968–1990: Old Federal States.] Data provided on 18 Jun 2015.

Destatis. (2014b). Lebendgeborene nach dem Alter der Mütter 1991–2013: Deutschland. [Live Births by Mothers‘ Age 1991–2013: Germany.] Data provided on 18 Jun 2015.

Destatis. (2015). Wanderungen zwischen Deutschland und dem Ausland 1991–2013 nach Einzelaltersjahren und Geschlecht. [Migration between Germany and abroad 1991–2013 by Years of Age and Sex.] Data provided on 02 Sept 2015.

Destatis. (2016a). Wanderungen zwischen Deutschland und dem Ausland 2014 nach Einzelaltersjahren und Geschlecht. [Migration between Germany and abroad 2014 by Years of Age and Sex.] Data provided on 13 Mar 2016.

Destatis. (2016b). Bevölkerung am 31.12.1950–2011 nach Alters- und Geburtsjahren. [Population on 31 December 1950–2011 by Year of Age and Birth.] Data provided on 17 Mar 2016.

Destatis. (2017a). Wanderungen zwischen Deutschland und dem Ausland 2015 nach Einzelaltersjahren und Geschlecht. [Migration between Germany and abroad 2014 by Years of Age and Sex.] Data provided on 23 Apr 2017.

Destatis. (2017b). Wanderungen über die Grenzen Deutschlands 1990–2015 nach ausgewählten Staatsangehörigkeiten/ der Staatsangehörigkeit und Altersgruppen. [German Cross-Border Migration 1990–2015 by selected Citizenships / Citizenship and Groups of Age.] Data provided on 18 Apr 2017.

Destatis. (2017c). Gestorbene 2000–2015 nach Alters- und Geburtsjahren. [Deaths 2000–2015 by Years of Age and Birth.] Data provided on 15 Aug 2017.

Destatis. (2018a). Wanderungen zwischen Deutschland und dem Ausland 2016 nach Einzelaltersjahren und Geschlecht. [Migration between Germany and abroad 2016 by Years of Age and Sex.] Data provided on 13 Mar 2018.

Destatis. (2018b). Wanderungen über die Grenzen Deutschlands 2016 nach der Staatsangehörigkeit und Altersgruppen. [Migration over the German Borders 2016 by Citizenship and Groups of Age.] Data provided on 25 Apr 2018.

Destatis. (2018c). Gestorbene 2016 nach Alters- und Geburtsjahren. [Deaths 2016 by Years of Age and Birth.] Data provided on 29 Mar 2018.

Destatis. (2018d). Lebendgeborene nach dem Alter der Mutter 1968–1969: DDR. [Live Births by Mother’s Age 1968–1969: GDR] Data provided on 08 Feb 2018.

Destatis. (2018e). Lebendgeborene nach dem Alter der Mutter 1970–1989: DDR. [Live Births by Mother’s Age 1970–1989: GDR] Data provided on 09 Feb 2018.

Destatis. (2018f). Wanderungen zwischen Deutschland und dem Ausland 2017 nach Einzelaltersjahren und Geschlecht. [Migration between Germany and abroad 2017 by Years of Age and Sex.] Data provided on 12 Apr 2019.

Destatis. (2018g). Wanderungen über die Grenzen Deutschlands 2017 nach der Staatsangehörigkeit und Altersgruppen. [Migration over the German Borders 2017 by Citizenship and Groups of Age.] Data provided on 12 Apr 2019.

Destatis. (2019a). Gestorbene 2017 nach Alters- und Geburtsjahren. [Deaths 2017 by Years of Age and Birth.] Data provided on 19 Mar 2019.

Destatis. (2019b). Bevölkerung im Wandel. Annahmen und Ergebnisse der 14. koordinierten Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung [Population in Transition. Assumptions and Results of the 14th Coordinated Population Projection]. Retrieved from the Destatis website: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Presse/Pressekonferenzen/2019/Bevoelkerung/pressebroschuere-bevoelkerung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. Accessed 13 Jul 2019.

Dickey, D. A., & Fuller, W. A. (1979). Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74(366), 427–431.

Dudel, C. (2014). Vorausberechnung von Verwandtschaft: Wie sich die gemeinsame Lebenszeit von Kindern, Eltern und Großeltern zukünftig entwickelt. [Forecasting of Relationship: How joint Lifetime of Children, Parents and Grandparents develops in the Future]. Opladen/Berlin/Toronto: Verlag Barbara Budrich.

European Union. (2015). The 2015 Aging report: Economic and budgetary projections for the 28 EU Member States (2013–2060). European Economy 3/2015. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Fuchs, J., Söhnlein, D., Weber, B., & Weber, E. (2018). Stochastic Forecasting of Labor Supply and Population: An Integrated Model. Population Research and Policy Review, 37(1), 33–58.

Gauthier, A. H., & Hatzius, J. (1997). Family benefits and fertility: An econometric analysis. Population Studies, 51(3), 295–306.

GENESIS-Online Datenbank. (2018). Durchschnittliches Alter der Mutter bei Geburt ihrer lebend geborenen Kinder: Deutschland, Jahre, Familienstand der Eltern. [Average Mother’s Age by Live Birth: Germany, Years, Parents’ Marital Status.] https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online/. Accessed 7 Mar 2018.

GENESIS-Online Datenbank. (2019a). Lebendgeborene: Deutschland, Jahre, Alter der Mutter, Geschlecht der Lebendgeborenen, Familienstand der Eltern. [Live Births: Germany, Years, Mother’s Age, Sex of Newborn, Parents’ Marital Status.] https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online/. Accessed 9 Jul 2019.

GENESIS-Online Datenbank. (2019b). Lebendgeborene: Deutschland, Jahre, Geschlecht. [Live Births: Germany, Years, Sex.] https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online/. Accessed 15 Jul 2019.

GENESIS-Online Datenbank. (2019c). Gestorbene: Deutschland, Jahre, Geschlecht. [Deaths: Germany, Years, Sex.] https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online/. Accessed 15 Jul 2019.

GENESIS-Online Datenbank. (2019d). Wanderungen zwischen Deutschland und dem Ausland: Deutschland, Jahre, Kontinente. [Migration between Germany and abroad: Germany, Years, Continents.] https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online/. Accessed 15 Jul 2019.

Härdle, W., & Myšičková, A. (2009). Stochastic population forecast for Germany and its consequence for the German Pension System (SFB 649 Discussion Paper 2009–009). Berlin: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research. (2017). Conflict barometer 2016. Heidelberg: Universität Heidelberg, Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict.

Helle, S., Helama, S., & Jokela, J. (2008). Temperature-related birth sex ratio bias in historical Sami: Warm years bring more sons. Biological Letters, 4(1), 60–62.

Hertrampf, S. (2008). Ein Tomatenwurf und seine Folgen: Eine neue Welle des Frauenprotestes in der BRD. [A tossed Tomato and its Results: A new Wave of Female Protest in the Federal Republic of Germany.] Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. Retrieved from https://www.bpb.de/gesellschaft/gender/frauenbewegung/35287/neue-welle-im-westen . Accessed 5 Mar 2019.

Human Mortality Database. (2019a). Germany, Deaths (Lexis triangle). Provided by University of California, Berkeley (USA), and Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany). Available at https://www.mortality.org. Data downloaded on 09 Jul 2019.

Human Mortality Database. (2019b). West Germany, Deaths (Lexis triangle). Provided by University of California, Berkeley (USA), and Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany). Available at https://www.mortality.org. Accessed 09 Jul 2019.

Human Mortality Database. (2019c). East Germany, Deaths (Lexis triangle). Provided by University of California, Berkeley (USA), and Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany). Available at https://www.mortality.org. Accessed 09 Jul 2019.

Human Mortality Database. (2019d). Germany, Population size (abridged). Provided by University of California, Berkeley (USA), and Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany). Available at https://www.mortality.org. Accessed 09 Jul 2019.

Human Mortality Database. (2019e). West Germany, Population size (abridged). Provided by University of California, Berkeley (USA), and Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany). Available at https://www.mortality.org. Accessed 09 Jul 2019.

Human Mortality Database. (2019f). East Germany, Population size (abridged). Provided by University of California, Berkeley (USA), and Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany). Available at https://www.mortality.org. Accessed 09 Jul 2019.

Hyndman, R. J., Booth, H., & Yasmeen, F. (2013). Coherent mortality forecasting: The product-ratio method with functional time series models. Demography, 50(1), 261–283.

Hyndman, R. J., & Ullah, M. S. (2007). Robust forecasting of mortality and fertility rates: A functional data approach. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 51(10), 4942–4956.

International Organization for Migration. (2014). Afghanistan: Migration profile. Kabul: International Organization for Migration.

James, W. H. (2000). Secular movements in sex ratios of adults and of births in populations during the past half-century. Human Reproduction, 15(5), 1178–1183.

Kalwij, A. (2010). The impact of family policy expenditure on fertility in Western Europe. Demography, 47(2), 503–519.

Keilman, N., Dinh, Q. P., & Hetland, A. (2002). Why population forecasts should be probabilistic – Illustrated by the case of Norway. Demographic Research, 6(15), 409–454.

Klüsener, S., Grigoriev, P., Scholz, R. D., & Jdanov, D. A. (2018). Adjusting inter-censal population estimates for Germany 1987-2011: Approaches and impact on demographic indicators. Comparative Population Studies, 43, 31–64.

Le Bras, H., & Tapinos, G. (1979). Perspectives à long terme de la population française et leurs implications économiques. [Long-term outlook of the French population and its economic implications.]. Population, 34(1), 1391–1452.

Ledermann, S., & Breas, J. (1959). Les dimensions de la mortalité. [The dimensions of mortality]. Population, 14(4), 637–682.

Lee, R. D. (1993). Modeling and forecasting the time series of US fertility: Age distribution, range, and ultimate level. International Journal of Forecasting, 9(2), 187–202.

Lee, R. D. (1998). Probabilistic approaches to population forecasting. Population and Development Review, 24(Supplement: Frontiers of Population Forecasting), 156–190.

Lee, R. D., & Carter, L. R. (1992). Modeling and forecasting U.S. mortality. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 87(419), 659–671.

Lipps, O., & Betz, F. (2005). Stochastische Bevölkerungsprojektion für West- und Ostdeutschland. [Stochastic population projection for western and eastern Germany.]. Zeitschrift für Bevölkerungswissenschaft (Comparative Population Studies), 30(1), 3–42.

Lutz, W., & Scherbov, S. (1998). Probabilistische Bevölkerungsprognosen für Deutschland. [Probabilistic Population Forecasts for Germany.]. Zeitschrift für Bevölkerungswissenschaft (Comparative Population Studies), 23(2), 83–109.

Luy, M., & Di Giulio, P. (2006). The impact of health behaviors and life quality on gender differences in mortality. (MPIDR Working Paper WP 2006-035). Rostock: Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research.

Mathews, F., Johnson, P. J., & Neil, A. (2008). You are what your mother eats: Evidence for maternal preconception diet influencing foetal sex in humans. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 275(1643), 1661–1668.

McKenzie, S. (2018). How seven years of war turned Syria’s cities into ‘hell on earth’. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2018/03/15/middleeast/syria-then-now-satellite-intl/index.html. Accessed 5 Mar 2019.

OECD. (2017). OECD-Wirtschaftsausblick 2017/2. [OECD Economic Outlook 2017/2]. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Pampel, F. (2005). Forecasting sex differences in mortality in high income nations: The contribution of smoking. Demographic Research, 13(18), 455–484.

Pearson, K. (1901). LIII. On lines and planes of closest fit to systems of points in space. Philosophical Magazine, Series 6, 2(11), 559–572.

Pleitgen, F. (2017). Inside Aleppo: Residents return to rebuild Syria’s shattered city. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2017/08/15/middleeast/aleppo-syria-rebuilds/index.html. Accessed 5 Mar 2019.

Pötzsch, O. (2016). (Un-)Sicherheiten der Bevölkerungsvorausberechnungen: Rückblick auf die koordinierten Bevölkerungsvorausberechnungen für Deutschland zwischen 1998 und 2015. [(Un-)Certainties about Population Projections: Review of the Coordinated Population Projections for Germany between 1998 and 2015]. WISTA – Wirtschaft und Statistik, 4, 36–54.

Pötzsch, O., & Rößger, F. (2015). Germany’s population by 2060: Results of the 13th coordinated population projection. Retrieved from the Destatis website: https://www.destatis.de/EN/Publications/Specialized/Population/GermanyPopulation2060_5124206159004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. Accessed 03 Aug 2018.

Raftery, A. E., Alkema, L., & Gerland, P. (2014a). Bayesian population projections for the United Nations. Statistical Science, 29(1), 58–68.

Raftery, A. E., Chunn, J. L., Gerland, P., & Ševčíková, H. (2013). Bayesian probabilistic projections of life expectancy for all countries. Demography, 50(3), 777–801.

Raftery, A. E., Lalić, N., & Gerland, P. (2014b). Joint probabilistic projection of female and male life expectancy. Demographic Research, 30(27), 795–822.

Schnabel, S., von Kistowski, K., & Vaupel, J. W. (2005). Immer neue Rekorde und kein Ende in Sicht: der Blick in die Zukunft lässt Deutschland grauer aussehen als viele erwarten. [Ever new Records and no End in Sight: A Look in the Future makes Germany look more gray than many expect]. Demografische Forschung Aus Erster Hand, 2(2), 3.

Scholz, R. D., Jdanov, D. A., Kibele, E., Grigoriev, P., & Klüsener, S. (2018). About mortality data for Germany. Human Mortality Database. https://www.mortality.org/hmd/DEUTNP/InputDB/DEUTNPcom.pdf. Accessed 9 July 2019.

Trovato, F., & Lalu, N. M. (1996). Narrowing sex differentials in life expectancy in the industrialized world: Early 1970’s and early 1990’s. Biodemography and Social Biology, 43(1), 20–37.

United Nations. (2015). World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision: Methodology of the United Nations Population Estimates and Projections (Working Paper No. ESA/P/WP.242). New York: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

United Nations. (2017). Probabilistic projection of total population (both sexes combined) by region, subregion, country or area, 2015–2100 (thousands). Retrieved from https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Download/Probabilistic/Population/. Accessed 11 Sept 2017.

Vanella, P. (2017). A principal component model for forecasting age- and sex-specific survival probabilities in Western Europe. Zeitschrift für die gesamte Versicherungswissenschaft (German Journal of Risk and Insurance), 106(5), 539–554.

Vanella, P. (2018). Stochastic Forecasting of Demographic Components Based on Principal Component Analyses. Athens Journal of Sciences, 5(3), 223–246.

Vanella, P., & Deschermeier, P. (2018). A stochastic Forecasting Model of international Migration in Germany. In O. Kapella, N. F. Schneider, & H. Rost (Eds.), Familie – Bildung – Migration: Familienforschung im Spannungsfeld zwischen Wissenschaft, Politik und Praxis. Tagungsband zum 5. Europäischen Fachkongress Familienforschung (pp. 261–280). Opladen/Berlin/Toronto: Verlag Barbara Budrich.

Vanella, P., & Deschermeier, P. (2019). A Principal Component Simulation of Age-Specific Fertility – Impacts of Family and Social Policy on Reproductive Behavior in Germany. Population Review, 58(1), 78–109.

Waldron, I. (1993). Recent trends in sex mortality ratios for adults in developed countries. Social Science & Medicine, 36(4), 451–462.

Whelpton, P. K. (1928). Population of the United States, 1925 to 1975. The American Journal of Sociology, 34(2), 253–270.

Wiśniowski, A., Smith, P. W. F., Bijak, J., Raymer, J., & Forster, J. J. (2015). Bayesian population forecasting: Extending the Lee-Carter method. Demography, 52(3), 1035–1059.

World Bank. (2019). Global economic prospects. Heightened tensions, subdued investment. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

World Health Organization. (2015). World report on ageing and health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Zeit Online. (2015). Deutschland setzt Dublin-Verfahren für Syrer aus. [Germany suspends Dublin procedure for Syrians.] Zeit. https://www.zeit.de/politik/ausland/2015-08/fluechtlinge-dublin-eu-asyl. Accessed 5 Mar 2019.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful remarks, which contributed to substantive improvements in the paper. Moreover, we appreciate the support by the Federal Statistical Office, who provided us with much of the input data for our study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendices

Appendix A: Forecast Functions of Principal Components

Migration Model

Labor Market Index (Principal Component 1):

-

yl being the year under study, with yl = 0 corresponding to the year 1990

-

ul(yl) being the autoregressive part in the ARIMA model specifying the difference between the observation in yl and the deterministic long-term trend specified by the model:

$$ {u}_l\left({y}_l\right):= l\left({y}_l\right)-\left[-\mathrm{23,943.514}+\mathrm{1,942.419}\ast {y}_l+\mathrm{3,646.207}\ast \sin \left(0.698\ast {y}_l-3.316\right)\right] $$ -

el(yl) being the nuisance parameter of the ARIMA model with \( {e}_l\sim \mathcal{NID}\left(0;{\mathrm{7,307.992}}^2\right)\forall {y}_l \)

Crises Index (Principal Component 2):

with

Principal Components 3–1463:

with

Mortality Model

Lee-Carter Index (Principal Component 1):

with

-

ym = 0 corresponding to the year 1995

$$ {e}_m\sim \mathcal{NID}\left(0;{0.299}^2\right)\forall {y}_m $$

Behavioral Index (Principal Component 2):

with

-

yb = 0 corresponding to the year 1990

$$ {e}_b\sim \mathcal{NID}\left(0;{0.158}^2\right)\forall {y}_b $$

Principal Components 3–209:

with

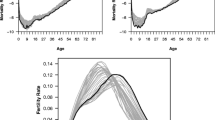

Fertility Model

Tempo Index (Principal Component 1):

with

-

ln() denoting the natural logarithm

-

yt = 0 corresponding to the year 1967

$$ {e}_t\sim \mathcal{NID}\left(0;{0.289}^2\right)\forall {y}_t $$

Quantum Index (Principal Component 2):

with

-

yq = 0 corresponding to the year 2010

$$ {e}_q\sim \mathcal{NID}\left(0;{0.216}^2\right)\forall {y}_q $$

Principal Components 3–37:

with

Appendix B: Selected Forecast Results for Three Age Groups

Explanations:

-

“Young” population means the population younger than age 20

-

“Working Age” addresses the population aged 20–66

-

“Old” population means persons aged 67 and older

Appendix C: Backtest for Forecast Accuracy

We have used the population data described in the data section until the year 2008 only, the year before the big migration influx described in the introduction occurred. Avoiding the structural break, which occurred in the data due to the 2011 Census (see also Section 3), we base the test on the last census before that, which occurred in 1987. The base population is the age- and sex-specific population on December 31, 2008. Since the dataset provided does not include detailed information for the population aged 95 and older, we estimated the distribution of the population in that age group by using the population estimates for December 31, 1999 and updating the respective cohorts using the age- and sex-specific numbers of deaths by cohort for the years 2000–2008. Migration in this case is ignored for the sake of simplicity. All of these data have been provided by Destatis on demand (Destatis 2016b, 2017c). Our model is now used for forecasting the age- and sex-specific population until December 31, 2018, following the same approach as that described in Section 3. To put the results in perspective, some selected results of Destatis’ (2009) 12th coordinated population projection, namely, the stated most probable middle assumptions alongside the two extreme scenarios, are compared with the hypothetical population numbers. We stress that this is not the actual population number, but rather the estimate of what the population number would have been, based on updating the 1987 Census estimate. To update this estimate, we annually increase the population by birth numbers and net migration, while subtracting the death numbers, starting at our estimate for the 2008 population numbers.

Figure 17 provides all these estimates for the period 2009 to 2018 alongside our model estimates of the median population and the 90% PIs.

Our median forecast would have performed similarly as poor as Destatis’ projection (not even their extreme scenarios have been able to capture any of the real population developments). However, Fig. 17 underlines the advantage of our probabilistic approach, as eight of the ten population estimates from the update are captured by our 90% PI, and even the two values outside the interval in 2015 and 2016 are just slightly outside of our interval bounds. Our model even managed to identify the extreme migration of the year 2015 as a possible, yet unlikely, scenario. This stresses the message advocated by us: It is extremely difficult to predict the future demographic development, especially when with regard to migration, but an appropriate stochastic approach covers all possible outcomes and quantifies them.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vanella, P., Deschermeier, P. A Probabilistic Cohort-Component Model for Population Forecasting – The Case of Germany. Population Ageing 13, 513–545 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-019-09258-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-019-09258-2