Abstract

Background

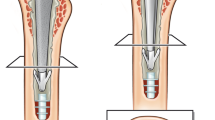

The literature suggests that a cemented long-stem femoral arthroplasty is associated with increased intraoperative and perioperative risks. Embolic events may precipitate cardiopulmonary complications and even death; by contrast, others have reported that the use of a cemented long-stem femoral arthroplasty in patients with metastatic bone disease is a safe procedure.

Questions/purposes

Specifically, in this study, we sought to identify (1) intraoperative complications potentially attributable to the use of cemented long-stem femoral components, and (2) early postoperative complications potentially attributable to the use of cemented long-stem femoral components in patients having an arthroplasty for metastatic bone disease.

Methods

In this study, we performed a retrospective chart review of 42 patients (44 arthroplasties), in which the same surgical technique was used. The primary outcome measure was perioperative complications, including intraoperative cement-associated desaturation, cement-associated hypotension, sympathomimetic administration, postoperative hypotension/desaturation, and death.

Results

In this series, 19% of the patients had cement-associated hypotension and sympathomimetics were administered to 48%. Two patients required prolonged intubation. One death occurred during hospitalization but there were no cardiopulmonary events.

Conclusions

This study showed that some patients experienced postoperative desaturation, prolonged intubation, and increased use of sympathomimetics, however, these events were short-lived and did not result in patient mortality. Although there are significant risks to cemented long-stem femoral arthroplasty, it can be performed with a low risk of fatal cardiopulmonary complications and remains a surgical option when treating patients with metastatic bone disease.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See Instructions for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Alvi HM, Damron TA. Prophylactic stabilization for bone metastases, myeloma, or lymphoma: do we need to protect the entire none? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:706–714.

Bickels J, Dadia S, Lidar Z. Surgical management of metastatic bone disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91;1503–1516.

Biermann JS, Holt GE, Lewis VO, Schwartz HS, Yaszemski MJ. Metastatic bone disease: diagnosis, evaluation and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1518–1530.

Chia SK, Speers CH, D’yachikova Y, Kang A, Malfair-Taylor S, Barnett J, Coldman A, Gelmon KA, O’reilly SE, Olivotta IA. The impact of new chemotherapeutic and hormone agents on survival in a population-based cohort of women with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:973–979.

Coleman R, Gnant M, Morgan G, Clezardin P. Effects of bone-targeted agents on cancer progression and mortality. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1059–1067.

Donaldson AJ, Thomson HE, Harper NJ, Kenny NW. Bone cement implantation syndrome. Br J Anaesth. 2009;102:12–22.

Fallon KM, Fuller JG, Morley-Forster P. Fat embolization and fatal cardiac arrest during hip arthroplasty with methylmethacrylate. Can J Anaesth. 2001;48:626–629.

Herrenbruck T, Erickson EW, Damron TA, Heiner J. Adverse clinical events during cemented long-stem femoral arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;395:154–163.

Mirels H. Metastatic disease in longs bones: a proposed scoring system for diagnosing impending pathologic fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;249:256–264.

Paulson OB, Strandsgaard S, Edvinsson L. Cerebral autoregulation. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev. 1990;2:161–192.

Randall RL, Aoki SK, Olson PR, Bott SI. Complications of cemented long-stem hip arthroplasties in metastatic bone disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;443:287–295.

Ryan CJ, Elkin EP, Cowan J, Carroll PR. Initial treatment patterns and outcome of contemporary prostate cancer patients with bone metastases at initial presentation: data from CaPSURE. Cancer. 2007;110:81–86.

Schulman KL, Kohles J. Economic burden of metastatic bone disease in the U.S. Cancer. 2007;109:2334–2342.

Selek H, Basarir K, Yildiz Y, Saglik Y. Cement endoprosthetic replacement for metastatic bone disease in the proximal femur. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:112–117.

Thein R, Herman A, Chechik A, Liberman B. Uncemented arthroplasty for metastatic disease of the hip: preliminary clinical experience. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27:1658–1662.

Weber KL, Randall RL, Grossman S, Parvizi J. Management of lower-extremity bone metastasis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(suppl 4):11–19.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

One author certifies that he (RLR) has received or may receive payments or benefits, during the study period, an amount of USD less than $10,000 from Biomet Orthopaedics, Inc, (Warsaw, IN, USA). One author certifies that he (SKA) has received or may receive payments or benefits, during the study period, an amount of USD less than $10,000 from Smith and Nephew, Inc (Memphis,TN, USA); an amount of USD less than $10,000 from ArthroCare Corp (Austin,TX, USA); and an amount of USD less than $10,000 from Pivot Medical (Sunnyvale,CA, USA).

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA.

About this article

Cite this article

Price, S.L., Farukhi, M.A., Jones, K.B. et al. Complications of Cemented Long-stem Hip Arthroplasty in Metastatic Bone Disease Revisited. Clin Orthop Relat Res 471, 3303–3307 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-013-3113-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-013-3113-5