Abstract

Purpose of Review

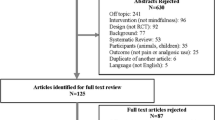

We aim to present current understanding and evidence for meditation, mostly referring to mindfulness meditation, for the management of acute pain and potential opportunities of incorporating it into the acute pain service practice.

Recent Findings

There is conflicting evidence concerning meditation as a remedy in acute pain. While some studies have found a bigger impact of meditation on the emotional response to a painful stimulus than on the reduction in actual pain intensities, functional Magnet Resonance Imaging has enabled the identification of various brain areas involved in meditation-induced pain relief.

Summary

Potential benefits of meditation in acute pain treatment include changes in neurocognitive processes. Practice and Experience are necessary to induce pain modulation. In the treatment of acute pain, evidence is emerging only recently. Meditative techniques represent a promising approach for acute pain in various settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Meditation is a contemplative practice that found its origins in Buddhism thousands of years ago [1••]. Over the past 40 years, these Buddhist traditions have made their way into the secular world as a way of promoting calmness and mental well-being [1••, 2••, 3]. Western medicine has also become increasingly interested in the potential benefits of meditation on mental and physical health [4] and the American Heart Association (AHA) states in their scientific statement on psychological health, well-being, and the mind-heart-body connection that “there is increasing evidence that psychological health may be causally linked to biological processes and behaviors that contribute to and cause (cardiovascular) disease” [5].

Meditation in a modern sense has been defined as “a family of self-regulation practices that focus on training attention and awareness in order to bring mental processes under greater voluntary control” [3]. Three common forms of meditation are focused attention meditation, mindfulness or open-monitoring meditation, and loving kindness or compassion meditation (Table 1). Mindfulness meditation has received much scientific attention in recent years, as it pursues a non-reactive form of sensory awareness [1••]. Mindfulness has been defined as “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” [2••]. During mindfulness practice, the practitioner observes their surroundings and monitors their sensations and internal dialogue, without becoming overly preoccupied with these perceptions. In this way, awareness of unpleasant sensations decreases the emotional response, an important notion that can be applied to understand the influence of mindfulness meditation on pain perception [1••].

The experience of pain is a complex construct and the exact neurobiological mechanisms through which mindfulness meditation can influence pain perception have until recently been poorly understood. Although meditation shares several characteristics with other self-regulation practices, such as psychotherapy or hypnosis—the two alternative treatment modalities for pain—these practices generally do not focus on training attention and awareness. Hypnotic techniques, as an example, generally influence mental contents on an unconscious level, such as through thoughts, images, or emotions, while meditation trains the ability to observe and control ongoing cognitive processes [3, 12]. After all, evidence regarding the use of meditation in relieving acute pain is still scarce. We present the findings of recent studies on the specific mechanisms of mindfulness meditation–induced pain relief. We describe specific brain regions that are involved in the cognitive processing and modulation of pain and the ways in which meditation interacts with these brain regions. We also summarize the current evidence provided by experimental and clinical studies that support the use of mindfulness meditation in patients suffering from acute pain and, based on these findings, we finally discuss how mindfulness meditation might be implemented in clinical practice.

The Concepts of Consciousness and Pain Perception

From a neurobiological perspective, meditation can be thought of as a modification of consciousness [2••]. Consciousness remains a complex concept due to its multidimensionality and the uniqueness of each human experience, which is shaped by sensory, affective, and cognitive aspects. Simply defined, consciousness is a cognitive state in which one is aware of the individual experience and the surrounding environment [13, 14]. Consciousness is dictated by the presence of wakefulness (level of consciousness) and awareness (context of consciousness) [14]. Additionally, neurobiological research divides the states of consciousness into two classes: global and local states of consciousness [15]. Global states describe changes in arousal and behavioral responses, such as wakefulness, dreaming, and sedation. Local states involve sensory, affective, and cognitive content. They describe the “experience of self,” which includes experiences of mood, emotion, volition, body ownership, and explicit autobiographical memory [15].

The understanding of pain perception, just as the concept of consciousness, is based on a multidimensional model involving sensory, affective, and cognitive aspects [13]. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that association with, actual or potential tissue damage” [16]. Although the processing of nociception is largely unconscious, the perception of pain requires a state of consciousness (wakefulness and awareness) that is influenced by psychological and cognitive factors [13, 14]. Traditional Buddhist texts have long suggested that pain perception is the result of both sensory and affective factors, and that trained meditators experience pain in a different way than untrained individuals. The original texts liken the physical and mental aspects of pain to being struck by two subsequential darts or arrows. While untrained individuals will be pierced by both arrows, experienced meditators will be able to influence their experience of pain by avoiding the second arrow, which represents the worry and distress caused by a painful event [7, 11, 12].

A Synopsis of Pain Physiology

Pain physiology is influenced by a complex network of interactions involving the autonomic, peripheral, and central nervous systems [17, 18], as well as the endocrine [19] and immune systems [20, 21]. Initial nociceptive information is conducted along primary afferent fibers to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord [22, 23]. From here, the information ascends to the thalamus via the spinothalamic tract and to specific areas in the brainstem via the spinomesencephalic and spinoreticular tracts [24]. From the thalamus, nociceptive information is projected to the cortex, where cognitive processing integrates sensory-discriminative (i.e., location and intensity) and affective-emotional (i.e., pain unpleasantness) aspects [17, 25•]. Research using positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has unmasked a complex network of brain regions that are involved in the cognitive processing and top-down modulation of pain [17, 25•]. In Table 2, we list the relevant brain regions involved in pain processing and modulation. We also summarize the mechanisms through which mindfulness meditation influences pain perception.

Meditation and Pain Modulation

Neuroimaging studies have recently provided insight into the neurocognitive mechanisms by which mindfulness meditation can influence pain perception [25•, 26, 50••, 51]. Current research suggests that the mechanisms of mindfulness meditation–induced pain relief are different in novice and experienced meditators. Brief meditation training (less than 10 h of practice) seems to be associated with top-down modulation of ascending nociceptive information in the thalamus by projections coming from higher-order brain regions that are involved in the cognitive processing of pain (Fig. 1) [25•, 26]. For example, studies have shown that reductions in pain intensity and pain unpleasantness are associated with activation of the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), the anterior cingulate cortex, and the anterior insula [28, 30]. Concurrently, there is a downregulation of signals in the thalamus and reduced activation of the area in the somatosensory cortex corresponding to the stimulation site [30]. This suggests the involvement of a cortico-thalamic gating mechanism, which reduces the thalamic transmission of nociceptive input to the somatosensory cortex [50••].

Brain regions involved in pain modulation by meditation (adapted from Tang, YY., Hölzel, B., and Posner, M. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat Rev Neurosci 16, 213–225 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3916 [40••]). ACC anterior cingulate cortex, IC insula, PFC prefrontal cortex, SI primary sensory cortex, SII secondary sensory cortex, PCC posterior cingulate cortex, PAG periaqueductal gray, RVM rostral ventral medulla, DH dorsal horn

In addition, mindfulness meditation in inexperienced practitioners reduces activation of the precuneus, which is a central node of the default mode network (DMN) [49]. In neuroscience, the DMN refers to a network of brain regions that are involved in appraisal and self-referential processing. It is characterized by oscillating activity between these regions, with increased activity during wakeful resting states (e.g., daydreaming, mind wandering) and decreased activity during attention-demanding tasks [52] (Ricard 2014). Recent studies have shown that mindfulness meditation not only reduces synchronization between the nodes of the DMN [34], but also between the DMN and the thalamus [29]. At the same time, mindfulness meditation increases connectivity between the DMN and the somatosensory cortices [34]. These data suggest that mindfulness meditation not only reduces pain through cortico-thalamic inhibition, as mentioned above, but may also modulate pain perception through reappraisal of the incoming nociceptive information [25•, 26, 50••].

In contrast, experimental data has shown that long-term mindfulness meditation training (more than 1000 h of practice) primarily influences pain perception through a reduction in pain unpleasantness rather than pain intensity [35, 53, 54]. Reduced pain unpleasantness in experienced meditators is associated with significantly increased activity in somatosensory regions and simultaneous deactivation of appraisal-related brain regions [35, 36]. By focusing on the sensory-discriminative rather than the affective-emotional aspects of incoming nociceptive information, mindfulness meditation can induce a mental shift, which effectively uncouples the affective and sensory processing centers of pain [48, 54, 55]. Furthermore, researchers have recently developed machine-learning techniques, which identify distinct fMRI activity patterns, or neural signatures, that are associated with the processing of pain intensity and pain modulation [56, 57]. Although both short- and long-term meditation training is associated with subjective pain relief, the neural signatures of novice and experienced meditators of fMRI imaging differ significantly when they are subjected to a painful stimulus [58]. This provides further evidence that pain modulation depends on specific mechanisms which are developed and enhanced through practice and experience [26].

Importantly, the described mechanisms of mindfulness meditation–induced pain relief are independent of the endogenous opioid pathway [59-60] and occur through mechanisms that are distinct from placebo [28, 61, 62]. Although mindfulness meditation and sham (or placebo) meditation both reduce pain intensity and pain unpleasantness, the effect of sham meditation is less pronounced. Healthy subjects performing sham meditation also show greater activation in key regulatory brain regions such as the thalamus and the DMN, which are downregulated in subjects performing mindfulness meditation [28]. Moreover, an infusion of naloxone does not reverse mindfulness meditation–induced reductions in pain intensity and pain unpleasantness [59]. Although the exact mechanism is unknown, naloxone-mediated blockade of opioid receptors can even enhance the effect of mindfulness meditation on pain intensity scores [63, 62]. Additionally, recent findings have implicated the autonomic nervous system as a mediator for mindfulness meditation–induced pain relief. A higher heart rate variability during mindfulness meditation, as a marker for increased parasympathetic activity, is strongly associated with lower pain unpleasantness when compared to sham meditation [61]. Although the precise mechanism of autonomic pain modulation remains unclear [18], these findings are in line with the idea that mindfulness meditation engages neural mechanisms that are distinct from placebo to reduce pain [64,65,66,67].

Meditation as a Remedy for Acute Pain

One of the main challenges in meditation research has been the lack of a standardized classification system for mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) [35, 54]. Clinical research on MBIs has mostly been based on methods first developed and described by Jon Kabat-Zinn and colleagues more than 40 years ago [68, 69]. Since then, much research has been devoted to the effect of MBIs in patients with chronic pain [70]. Despite substantial heterogeneity among the available data, there is now consensus that MBIs can have a positive effect on pain intensity and the quality of life in patients with chronic pain [70, 71]. In acute pain research, the effect of MBIs has mainly been examined in healthy volunteers in experimental settings, although there has recently been an increase in clinical studies [72]. Experimental data show that even brief periods of provider-led mindfulness meditation training (3–4 days) in inexperienced subjects can significantly reduce pain intensity and pain unpleasantness [28, 30, 73]. A 20-min training session, followed by 2 weeks of self-practice at home, has also been found to increase pain thresholds and provide a more rapid attenuation of pain intensity in healthy volunteers [74]. Since meditation training is usually time intensive, the potential benefits of such brief MBIs provide new perspectives for the integration of meditation in everyday clinical practice [75].

Current research suggests that brief MBIs can be successfully implemented in hospitalized patients suffering from anxiety and acute pain and in the perioperative setting [76]. In hospitalized patients with either “intolerable pain” or “inadequate pain control,” approximately one-third of the patients treated with a single 15-min MBI reported at least a 30% reduction in pain intensity, which is comparable to a dose of 5 mg oxycodone [48]. Similarly, in patients admitted to a surgical center with acute pain due to different medical problems (e.g., infection, bowel obstruction, trauma), a 10-min MBI was able to significantly reduce pain intensity and pain-related stress [77]. In patients planned for total knee or hip joint arthroplasty, a single 15-min MBI reduced preoperative pain intensity from degenerative joint disease by 27%. In addition, patients showed reductions in pain unpleasantness, anxiety, and the desire for pain medication. Moreover, patients in the MBI group showed significantly better physical function at the 6 weeks postoperative evaluation [78]. As some authors have demonstrated, the preoperative evaluation of surgical patients provides an excellent opportunity to offer professional instruction and distribute educational materials for later self-practice [76, 79].

Furthermore, MBIs have been associated with beneficial outcomes for patients undergoing painful medical procedures. In dental surgery, 30–40 min of preoperative heartfulness meditation was associated with reduced intraoperative anxiety (although it had no effect on intraoperative pain intensity) [80]. In women undergoing stereotactic breast biopsy, studies employing mindfulness meditation and loving kindness meditation have shown mixed results on intraoperative pain intensity [81-82]. On the other hand, these studies also demonstrated that meditation provides relief from intraoperative anxiety and discomfort. Additionally, although a weekend mindfulness meditation course did not improve labor pain or reductions in epidural use in pregnant women going through childbirth, it did lower the need for opioid analgesia during labor [83]. An opioid-sparing effect has also been suggested by a recent meta-analysis evaluating MBIs in patients with clinical pain managed by opioids, although the study was not specific to acute pain [84]. Therefore, future research investigating MBIs as a remedy for acute pain might demonstrate further opportunities to treat acute pain in different clinical contexts and possibly contribute to the prevention of postoperative chronic pain and opioid misuse [85].

Conclusion

Meditation-supported pain relief is based on changes in neurocognitive processes that can be identified through neuroimaging studies. The mechanisms through which meditation influences pain modulation evolve with practice and experience. Although the benefits of meditation for patients with pain have been well-established, current evidence for the treatment of acute pain is just about to emerge and supports meditation as a promising perspective for the treatment of patients suffering from acute pain in various clinical settings.

Availability of Data and Material

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

•• Ricard M, Lutz A, Davidson RJ. Mind of the meditator. Sci Am. 2014;311(5):38–45. The author provides the most important basic insights into meditation from a scientific standpoint in this publication.

•• Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2003;10(2):144–56. A holistic overview of mindfulness-based meditation and its use in every-day—clinical practice from the early days up to very recently is provided by the authors in this manuscript.

Walsh R, Shapiro SL. The meeting of meditative disciplines and Western psychology: a mutually enriching dialogue. Am Psychol. 2006;61(3):227–39.

Creswell JD. Mindfulness interventions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2017;68:491–516.

Levine GN, Cohen BE, Commodore-Mensah Y, Fleury J, Huffman JC, Khalid U, et al. Psychological health, well-being, and the mind-heart-body connection: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143(10):e763–83.

Lutz A, Slagter HA, Dunne JD, Davidson RJ. Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12(4):163–9.

Acharya PSS. Eternity of sound and the science of mantras. 1st ed. Hardiwar: Yugantar Chetna Press; 2003.

Brandmeyer T, Delorme A, Wahbeh H. The neuroscience of meditation: classification, phenomenology, correlates, and mechanisms. Prog Brain Res. 2019;244:1–29.

Dahl CJ, Lutz A, Davidson RJ. Reconstructing and deconstructing the self: cognitive mechanisms in meditation practice. Trends Cogn Sci. 2015;19(9):515–23.

Fredrickson BL, Boulton AJ, Firestine AM, Van Cappellen P, Algoe SB, Brantley MM, et al. Positive emotion correlates of meditation practice: a comparison of mindfulness meditation and loving-kindness meditation. Mindfulness (N Y). 2017;8(6):1623–33.

Flavell JH. Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: a new area of cognitive—developmental inquiry. Am Psychol. 1979;34(10):906–11.

Penazzi G, De Pisapia N. Direct comparisons between hypnosis and meditation: a mini-review. Front Psychol. 2022;13: 958185.

Grant JA, Zeidan F. Employing pain and mindfulness to understand consciousness: a symbiotic relationship. Curr Opin Psychol. 2019;28:192–7.

Sgourdou P. The consciousness of pain: a thalamocortical perspective. NeuroSci. 2022;3(2):311–20.

Seth AK, Bayne T. Theories of consciousness. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2022;23(7):439–52.

Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M, Finnerup NB, Flor H, Gibson S, et al. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. 2020;161(9):1976–82.

Morton DL, Sandhu JS, Jones AK. Brain imaging of pain: state of the art. J Pain Res. 2016;9:613–24.

Kirkpatrick DR, McEntire DM, Hambsch ZJ, Kerfeld MJ, Smith TA, Reisbig MD, et al. Therapeutic basis of clinical pain modulation. Clin Transl Sci. 2015;8(6):848–56.

Chen Q, Zhang W, Sadana N, Chen X. Estrogen receptors in pain modulation: cellular signaling. Biol Sex Differ. 2021;12(1):22.

Baral P, Udit S, Chiu IM. Pain and immunity: implications for host defence. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19(7):433–47.

Xu M, Bennett DLH, Querol LA, Wu LJ, Irani SR, Watson JC, et al. Pain and the immune system: emerging concepts of IgG-mediated autoimmune pain and immunotherapies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(2):177–88.

Yam MF, Loh YC, Tan CS, Khadijah Adam S, Abdul Manan N, Basir R. General pathways of pain sensation and the major neurotransmitters involved in pain regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(8).

Harding EK, Fung SW, Bonin RP. Insights into spinal dorsal horn circuit function and dysfunction using optical approaches. Front Neural Circuits. 2020;14:31.

Tracey I, Mantyh PW. The cerebral signature for pain perception and its modulation. Neuron. 2007;55(3):377–91.

• Jinich-Diamant A, Garland E, Baumgartner J, Gonzalez N, Riegner G, Birenbaum J, et al. Neurophysiological mechanisms supporting mindfulness meditation-based pain relief: an updated review. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2020;24(10):56. This is the latest review summarizing the neurophysiology behind mindfulness meditation as a remedy for pain with a focus on chronic pain.

Zeidan F, Vago DR. Mindfulness meditation-based pain relief: a mechanistic account. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1373(1):114–27.

De Ridder D, Adhia D, Vanneste S. The anatomy of pain and suffering in the brain and its clinical implications. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;130:125–46.

Zeidan F, Emerson NM, Farris SR, Ray JN, Jung Y, McHaffie JG, et al. Mindfulness meditation-based pain relief employs different neural mechanisms than placebo and sham mindfulness meditation-induced analgesia. J Neurosci. 2015;35(46):15307–25.

Riegner G, Posey G, Oliva V, Jung Y, Mobley W, Zeidan F. Disentangling self from pain: mindfulness meditation–induced pain relief is driven by thalamic–default mode network decoupling. Pain. 2023;164(2):280–91.

Zeidan F, Martucci KT, Kraft RA, Gordon NS, McHaffie JG, Coghill RC. Brain mechanisms supporting the modulation of pain by mindfulness meditation. J Neurosci. 2011;31(14):5540–8.

Johansen JP, Fields HL, Manning BH. The affective componant of pain in rodents: direct evidence for a contribnution of the anterior cingulare cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98(14):8077–82.

Sun G, McCartin M, Liu W, Zhang Q, Kenefati G, Chen ZS, et al. Temporal pain processing in the primary somatosensory cortex and anterior cingulate cortex. Mol Brain. 2023;16(1):3.

Liang M, Mouraux A, Iannetti GD. Parallel processing of nociceptive and non-nociceptive somatosensory information in the human primary and secondary somatosensory cortices: evidence from dynamic causal modeling of functional magnetic resonance imaging data. J Neurosci. 2011;31(24):8976–85.

Harrison R, Zeidan F, Kitsaras G, Ozcelik D, Salomons TV. Trait mindfulness is associated with lower pain reactivity and connectivity of the default mode network. J Pain. 2019;20(6):645–54.

Gard T, Holzel BK, Sack AT, Hempel H, Lazar SW, Vaitl D, et al. Pain attenuation through mindfulness is associated with decreased cognitive control and increased sensory processing in the brain. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22(11):2692–702.

Grant JA, Courtemanche J, Rainville P. A non-elaborative mental stance and decoupling of executive and pain-related cortices predicts low pain sensitivity in Zen meditators. Pain. 2011;152(1):150–6.

Kulkarni B, Bentley DE, Elliott R, Youell P, Watson A, Derbyshire SW, et al. Attention to pain localization and unpleasantness discriminates the functions of the medial and lateral pain systems. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21(11):3133–42.

Roy M, Piché M, Chen J-I, Perez IO, Rainville P. Cerebral and spinal modulation of pain by emotions. The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106(49):20900–5.

Tolomeo S, Christmas D, Jentzsch I, Johnston B, Sprengelmeyer R, Matthews K, et al. A causal role for the anterior mid-cingulate cortex in negative affect and cognitive control. Brain. 2016;139(Pt 6):1844–54.

•• Tang YY, Holzel BK, Posner MI. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(4):213–25. The authors provide a sound description of the neurologic basis behind mindfulness meditation including modulating pathways in pain perception and pain experience.

Jensen KB, Regenbogen C, Ohse MC, Frasnelli J, Freiherr J, Lundstrom JN. Brain activations during pain: a neuroimaging meta-analysis of patients with pain and healthy controls. Pain. 2016;157(6):1279–86.

Chang LJ, Yarkoni T, Khaw MW, Sanfey AG. Decoding the role of the insula in human cognition: functional parcellation and large-scale reverse inference. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23(3):739–49.

Simons LE, Moulton EA, Linnman C, Carpino E, Becerra L, Borsook D. The human amygdala and pain: evidence from neuroimaging. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(2):527–38.

Ong WY, Stohler CS, Herr DR. Role of the prefrontal cortex in pain processing. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56(2):1137–66.

Coulombe MA, Erpelding N, Kucyi A, Davis KD. Intrinsic functional connectivity of periaqueductal gray subregions in humans. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016;37(4):1514–30.

Roy M, Shohamy D, Wager TD. Ventromedial prefrontal-subcortical systems and the generation of affective meaning. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16(3):147–56.

Seminowicz DA, Moayedi M. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in acute and chronic pain. J Pain. 2017;18(9):1027–35.

Garland EL, Baker AK, Larsen P, Riquino MR, Priddy SE, Thomas E, et al. Randomized controlled trial of brief mindfulness training and hypnotic suggestion for acute pain relief in the hospital setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(10):1106–13.

Zeidan F, Salomons T, Farris SR, Emerson NM, Adler-Neal A, Jung Y, et al. Neural mechanisms supporting the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and pain. Pain. 2018;159(12):2477–85.

•• Zeidan F, Baumgartner JN, Coghill RC. The neural mechanisms of mindfulness-based pain relief: a functional magnetic resonance imaging-based review and primer. Pain Rep. 2019;4(4): e759. (This manuscript provides an overview of the most recent findings regarding neuronal mechanisms involved in meditation-induced pain relief.)

De Benedittis G. Neural mechanisms of hypnosis and meditation-induced analgesia: a narrative review. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2021;69(3):363–82.

Raichle ME. The brain’s default mode network. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2015;38:433–47.

Perlman DM, Salomons TV, Davidson RJ, Lutz A. Differential effects on pain intensity and unpleasantness of two meditation practices. Emotion. 2010;10(1):65–71.

Zorn J, Abdoun O, Bouet R, Lutz A. Mindfulness meditation is related to sensory-affective uncoupling of pain in trained novice and expert practitioners. Eur J Pain. 2020;24(7):1301–13.

Garland EL, Gaylord SA, Palsson O, Faurot K, Douglas Mann J, Whitehead WE. Therapeutic mechanisms of a mindfulness-based treatment for IBS: effects on visceral sensitivity, catastrophizing, and affective processing of pain sensations. J Behav Med. 2012;35(6):591–602.

Wager TD, Atlas LY, Lindquist MA, Roy M, Woo CW, Kross E. An fMRI-based neurologic signature of physical pain. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(15):1388–97.

Woo CW, Schmidt L, Krishnan A, Jepma M, Roy M, Lindquist MA, et al. Quantifying cerebral contributions to pain beyond nociception. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14211.

Wielgosz J, Kral TRA, Perlman DM, Mumford JA, Wager TD, Lutz A, et al. Neural signatures of pain modulation in short-term and long-term mindfulness training: a randomized active-control trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179(10):758–67.

Zeidan F, Adler-Neal AL, Wells RE, Stagnaro E, May LM, Eisenach JC, et al. Mindfulness-meditation-based pain relief is not mediated by endogenous opioids. J Neurosci. 2016;36(11):3391–7.

Wells RE, Collier J, Posey G, Morgan A, Auman T, Strittmatter B, et al. Attention to breath sensations does not engage endogenous opioids to reduce pain. Pain. 2020;161(8):1884–93.

Adler-Neal AL, Waugh CE, Garland EL, Shaltout HA, Diz DI, Zeidan F. The role of heart rate variability in mindfulness-based pain relief. J Pain. 2020;21(3–4):306–23.

Case L, Adler-Neal AL, Wells RE, Zeidan F. The role of expectations and endogenous opioids in mindfulness-based relief of experimentally induced acute pain. Psychosom Med. 2021;83(6):549–56.

May LM, Kosek P, Zeidan F, Berkman ET. Enhancement of meditation analgesia by opioid antagonist in experienced meditators. Psychosom Med. 2018;80(9):807–13.

Thera tftPbN. Sallatha Sutta: the Dart (SN 36.6): Buddhist Publication Society; 1983 updated 13 june 2010. Access to Insight (BCBS Edition): Available from: http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/sn/sn36/sn36.006.nypo.html.

Nicolardi V, Simione L, Scaringi D, Malinowski P, Yordanova J, Kolev V, et al. The two arrows of pain: mechanisms of pain related to meditation and mental states of aversion and identification. Mindfulness. 2022.

Coelho BA. Extremely brief mindfulness interventions for women undergoing breast biopsies: a randomized controlled trial. 2018.

Ratcliff CG, Prinsloo S, Chaoul A, Zepeda SG, Cannon R, Spelman A, et al. A randomized controlled trial of brief mindfulness meditation for women undergoing stereotactic breast biopsy. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(5):691–9.

Wielgosz J, Goldberg SB, Kral TRA, Dunne JD, Davidson RJ. Mindfulness meditation and psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2019;15:285–316.

Kabat-Zinn J. Some reflections on the origins of MBSR, skillful means, and the trouble with maps. Contemporary Buddhism. 2011;12(1):281–306.

Reiner K, Tibi L, Lipsitz JD. Do mindfulness-based interventions reduce pain intensity? A critical review of the literature. Pain Med. 2013;14(2):230–42.

Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, Apaydin E, Xenakis L, Newberry S, et al. Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(2):199–213.

Shires A, Sharpe L, Davies JN, Newton-John TRO. The efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions in acute pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2020;161(8):1698–707.

Davies JN, Sharpe L, Day MA, Colagiuri B. Mindfulness-based analgesia or placebo effect? The development and evaluation of a sham mindfulness intervention for acute experimental pain. Psychosom Med. 2021;83(6):557–65.

Reiner K, Granot M, Soffer E, Lipsitz JD. A brief mindfulness meditation training increases pain threshold and accelerates modulation of response to tonic pain in an experimental study. Pain Med. 2016;17(4):628–35.

McClintock AS, McCarrick SM, Garland EL, Zeidan F, Zgierska AE. Brief mindfulness-based interventions for acute and chronic pain: a systematic review. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(3):265–78.

Luedi MM. At induction a crash course in Tonglen. Anesth Analg [In Press]. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000006050.

Miller-Matero LR, Coleman JP, Smith-Mason CE, Moore DA, Marszalek D, Ahmedani BK. A brief mindfulness intervention for medically hospitalized patients with acute pain: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Pain Med. 2019;20(11):2149–54.

Hanley AW, Gililland J, Erickson J, Pelt C, Peters C, Rojas J, et al. Brief preoperative mind-body therapies for total joint arthroplasty patients: a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2021;162(6):1749–57.

Grutz K, Poch N. Meditation for preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain in bariatric surgery. J Perianesth Nurs. 2021;36(5):586–90.

Gurram P, Narayanan V, Chandran S, Ramakrishnan K, Subramanian A, Kalakumari AP. Effect of heartfulness meditation on anxiety and perceived pain in patients undergoing impacted third molar surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021;79(10):2060 e1–e7.

Soo MS, Jarosz JA, Wren AA, Soo AE, Mowery YM, Johnson KS, et al. Imaging-guided core-needle breast biopsy: impact of meditation and music interventions on patient anxiety, pain, and fatigue. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13(5):526–34.

Wren AA, Shelby RA, Soo MS, Huysmans Z, Jarosz JA, Keefe FJ. Preliminary efficacy of a lovingkindness meditation intervention for patients undergoing biopsy and breast cancer surgery: a randomized controlled pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(9):3583–92.

Duncan LG, Cohn MA, Chao MT, Cook JG, Riccobono J, Bardacke N. Benefits of preparing for childbirth with mindfulness training: a randomized controlled trial with active comparison. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):140.

Garland EL, Brintz CE, Hanley AW, Roseen EJ, Atchley RM, Gaylord SA, et al. Mind-body therapies for opioid-treated pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(1):91–105.

Roberts RL, Hanley AW, Garland EL. Mindfulness-based interventions for perioperative pain management and opioid risk reduction following surgery: a stepped care approach. Am Surg. 2022:31348221114019.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Bern

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Flavia Wipplinger, Niels Holthof, Lukas Andereggen, Richard D. Urman, Markus M. Luedi, and Corina Bello conducted literature searches, wrote the article, and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

Flavia Wipplinger, Niels Holthof, Lukas Andereggen, Markus M. Luedi, and Corina Bello declare no conflict of interest. Richard D. Urman reports fees/funding from AcelRx, Medtronic, Pfizer, and Merck.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wipplinger, F., Holthof, N., Andereggen, L. et al. Meditation as an Adjunct to the Management of Acute Pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep 27, 209–216 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-023-01119-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-023-01119-0