Abstract

Background

Mothers of children with motor disabilities face physical and emotional burdens.

Aims

This study aimed to determine the physical activity levels, exercise-related barriers, and facilitators in mothers of children with motor disabilities and investigate the differences between the physical activity levels of mothers who have children with different motor functional status.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, mothers were assessed with the Exercise Benefits/Barriers Scale (EBBS) and International Physical Activity Questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF). The motor functional status of the children was classified by Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS), and the mothers were divided into two groups (GMFCS level I, II = mild motor disability n = 28, GMFCS level III–V = moderate-to-severe motor disability, n = 37) according to the motor level of their children.

Results

Sixty-nine mothers (36.56 ± 7.25 65) were included in this study. None of the mothers had adequate levels of physical activity (0%). According to the EBBS, the most frequently reported exercise barrier was lack of time (mothers of children with mild motor disability n = 26, 92.85%, the mothers of children with moderate-to-severe motor disability n = 34, 91.89%). The physical activity levels of the mothers of children with mild motor disability were higher compared to the mothers of children with moderate-to-severe motor disability (p = 0.032).

Conclusion

This study has revealed that the physical activity levels of mothers of children with motor disabilities are low, and this is related to the gross motor function level of the children. The focus should be on increasing the physical activity levels of mothers of children with motor disabilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Developmental disability is a group of conditions related to problems with cognitive, behavioral, or physical functioning [1]. Unfortunately, the number of children with a developmental disability is increasing day by day [2, 3].

Disease-specific needs of children with developmental disabilities often lead to a heavier physical and emotional burden on their parents [4]. There are also an increasing number of studies linking having a child with a developmental disability to parental poor physical health. These studies provide evidence that caregivers of children with developmental problems are in worse physical condition than parents of typically developing children [5, 6].

In recent years, the medical intervention model has been discontinued, and family-centered service and parent coaching have become prominent in the rehabilitation of children with developmental disabilities [7, 8]. In this regard, the parents of children with a developmental disability are one of the most essential parts of the rehabilitation team. Particularly, mothers have a fundamental role in managing the many factors that affect children’s health and reach to therapy services [9].

Mothers of children with a disability face challenge to satisfy their own health needs [10]. Cerebral palsy (CP) is the leading cause of motor disability in childhood [1]. Mothers of children with CP spend a significant amount of time caring for their children [11]. With the active participation of mothers in the rehabilitation of children with disabilities, therapy goals can be achieved in a shorter time. Therefore, it is essential to protect the physical and mental health of mothers.

The importance of physical activity and exercise for the protection and development of health has been explained by various organizations, especially the World Health Organization (WHO), and it has been stressed that physical activity levels should be enhanced. According to the WHO guidelines, all adults should engage in regular physical activity. Adults should undertake at least 150–300 min of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity or at least 75–150 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate-to-vigorous-intensity activity, per week for significant health benefits [12]. According to a study conducted to investigate the quality of life of parents of children with developmental disabilities according to their physical activity status, the quality of life of parents who engaged in physical activity was higher compared to parents who did not [13].

In this regard, it is critical to consider the health-related parameters and physical activity levels of mothers of children with motor disabilities [4]. In the literature, there are numerous studies on the stress and depression levels of mothers of children with motor disabilities. However, there is no study investigating the effects of the child’s motor level on the mother’s physical activity level. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the level of physical activity and perceived barriers to exercise, which can be modified in mothers of children with motor disabilities. Furthermore, the differences between the physical activity levels of mothers of children with different motor function levels were investigated.

Methods

This study was designed as a prospective cross-sectional study. The subjects included in this study were selected voluntarily among children with motor disability and their mothers who received treatment in Sivas Numune Hospital Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Unit, Destek Special Education and Rehabilitation Center. Many conditions or diseases that begin in childhood can cause motor and/or sensory disability in children. Therefore, children with the following diseases or conditions diagnosed by the physician were gathered under the umbrella of children with motor disability: CP, spinal and peripheral nerve lesions, neuromuscular diseases, genetic syndromes, or various syndromes causing motor disability.

Mothers of children with motor disabilities aged 0–18 were included in the study. All the mothers included in this study were primary caregivers of their children and living together with the child. Since the Turkish versions of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form (IPAQ-SF) and Exercise Benefits/Barriers Scale (EBBS) were used in the study, non-Turkish-speaking mothers were excluded from the study. Furthermore, mothers with other health conditions diagnosed by a physician such as a known history of musculoskeletal problems, hereditary disorders, trauma, or cardiovascular problems that would prevent them from doing physical activity; mothers with a new pregnancy; and mothers who care for another patient/child with a disability were excluded from the study.

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval for the study was granted by Ethics Committee of the Non-invasive Clinical Trials of Sivas Cumhuriyet University (Decision number: 2019-10/10, Decision Date: October 9, 2019). Data were collected from January 2020 to June 2020. Mothers and their children were informed about the study. The purpose and content of the study were explained to the mothers, and their written consents were obtained. Demographic and clinical information of the mothers and their children, such as gender, age, body mass (kg), and diagnosed health condition, were recorded.

Evaluation of physical activity level

The physical activity levels of mothers were evaluated by the IPAQ-SF [14, 15]. In the short form, there are seven questions related to the time spent in walking, moderate activities, vigorous activities, and the frequency of activities in the previous 7 days. The time spent sitting was assessed as a separate question. The durations are multiplied by the metabolic equivalents (MET) present in the scale for each activity and the average of the results for all materials presents the overall physical activity score. Physical activity levels are classified as physically inactive (< 600 MET-min/week), low physical activity level (600–3000 MET-min/week), and adequate physical activity level (> 3000 MET-min/week) [14]. The IPAQ-SF has adequate psychometric properties to assess the physical activity levels of individuals aged 18–65 [14, 15].

Evaluation of exercise benefits/barriers

The EBBS was applied to identify exercise-related barriers and facilitators for mothers of children with motor disabilities [16]. This scale is a 4-point Likert-type scale composed of a 14-item barrier scale and a 29-item benefit scale. The scoring of the scale is as follows: Strongly agree (4), agree (3), disagree (2), strongly disagree (1). The lowest score of the benefits scale is 29 while the highest score is 116. A high score indicates positive exercise perception. The score range of the barriers scale is between 14 and 56 points. High scores from the barriers scale indicate that individuals have perceived barriers to exercise [17].

Evaluation of the gross motor function level of the children

The extended and revised version of the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) was applied to evaluate the gross motor function levels of children [18]. So as to determine the functional level by means of the GMFCS; the use of mobility devices and their performance in sitting, standing, and walking activities are evaluated. The GMFCS consists of five different level classifications for five different age groups. The age groups are divided into 0–2, 2–4, 4–6, 6–12, and 12–18. GMFCS Level I represents the best and Level V represents the lowest motor function. GMFCS has been confirmed to be reliable and valid in the evaluation of children, particularly with CP [19]. Children’s GMFCS levels were assessed by a physical therapist experienced in pediatric rehabilitation. Subsequent to determining the gross motor function levels of the children, the mothers were divided into two groups based on the motor levels of their children. Mothers of the children at the GMFCS level I and II were classified under the Mothers of Children with Mild Motor Disabilities group, and mothers of the children at the GMFCS level III, IV, and V were classified under the Mothers of Children with Moderate-to-severe Motor Disabilities group.

Statistical analysis

The software SPSS, version 22.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0, IBM Company, Armonk, New York, USA) was used to analyze the data acquired from our study. The continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and the categorical variables as counts and percentages. In the physical activity barriers and facilitators scale, the answers “strongly agree” and “agree” were narrowed to the “agree” category, and the answers “strongly disagree” and “disagree” were narrowed to the “disagree” category. The conformity of the variables to the normal distribution was assessed by means of the Kolmogrov-Smirnov test. Since the parametric test assumptions were not to be fulfilled in the evaluation of the data, the Mann–Whitney U test was applied to compare the physical activity levels of mothers of children with motor disabilities. The level of significance was taken as 0.05 in all analyses.

Results

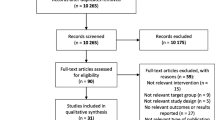

To be included in the study, 99 mothers of children with motor disabilities were reached out to, and 22 mothers did not meet the inclusion criteria (5 mothers with children over the age of 18, 5 mothers with children had an only mental disability, 12 mothers with health problems that would prevent them from doing physical activity), and 12 mothers were not included in the evaluation process due to missing answers in their questionnaires (Fig. 1). Mothers with a mean age of 36.56 ± 7.25 participated in the study.

Mothers’ education levels, employment status, marital status, physical activity levels, and the EBBS scores are presented in Table 1. Most of the mothers participating in the study were married (n = 63, 91.30%), and they were not in active working life (n = 61, 88.40%). According to the IPAQ-SF results, 54 (83.06%) of the mothers were determined to be not physically active (< 600 MET-min/week) and 11 (16.92%) to be at low physical activity level (600–3000 MET-min/week). None of the mothers were at an adequate level of physical activity (> 3000 MET-min/week). Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics and evaluation findings of the mothers.

The children of the participant mothers in the study had different diagnoses that caused motor disability. Their diagnoses were CP (75.38%), hydro/microcephaly (9.23%), obstetric brachial plexus paralysis (3.07%), Down syndrome (1.53%), neuromuscular diseases (3.07%), and spina bifida (7.69%). The number of children at the GMFCS level I and II (mild motor disability) was 28 (43.07%), and the children at the GMFCS level III, IV, and V (moderate-to-severe motor disability) were 37 (56.93%).

According to the EBBS, the most frequently reported exercise barrier was item 24: Exercise takes too much time from family relationships (mothers of children with mild motor disability = 92.85%, mothers of children with moderate-to-severe motor disability = 34 91.89%). The most frequently reported facilitator was item 13: Exercising will keep me from having high blood pressure (mothers of children with mild motor disability = 92.85%, mothers of children with moderate-to-severe motor disability = 97.29%), and participant answers to the EBBS are exhibited in Tables 2 and 3.

A comparison of the physical activity levels of the mothers of children with mild motor disabilities and the mothers of children with a moderate-to-severe motor disabilities determined a significant difference in terms of the IPAQ-SF total physical activity score (p = 0.032). The physical activity levels of the mothers of children with mild motor disability were higher compared to the mothers of children with moderate-to-severe motor disability. The comparison of the IPAQ-SF results of the mothers is presented in Table 4.

Discussion

This study; which aims to investigate the level of physical activity, exercise-related barriers, and facilitators in mothers of children with motor disability; revealed that the physical activity levels of the mothers of the children with mild motor disability were higher compared to the mothers of the children with moderate-to-severe motor disability, and none of the mothers had adequate physical activity levels.

Various studies in the literature have concluded that physical activity levels in healthy adults are extremely low and that physical activity levels of women are lower compared to men [20,21,22]. A study conducted in 2019 investigated the physical activity levels in 1975 healthy women aged between 18 and 64 who were registered to two different family medicine clinics. Out of them, 69.1% of the participant women were determined to be inactive, and only 30.0% were determined to be physically active [23]. Although physical activity levels vary depending on the personal and environmental differences of individuals, the physical activity levels of healthy women are observed to be generally low. Coinciding with these studies, our study yielded low physical activity levels of mothers. None of the mothers had adequate physical activity levels.

There are numerous factors that affect the physical activity levels of healthy individuals. These are gender, educational background, knowledge level about physical activity and health, marital status, socio-economic status, insufficient time, fatigue, dislike of exercise, motivation, self-confidence, mental state of the person, smoking-alcohol use, family-friend support, and other factors such as accessibility to the physical activity spaces and weather conditions [24]. The literature has revealed that mothers of children with disabilities cannot allocate time to recreational activities and do not have enough time for routine activities of daily living. Dehghan et al. [9] stated that women with children with CP neglect their own health needs while seeking ways to minimize the barriers faced by their children. The reasons for this are to constantly take care of the child with a disability and the obligation to substitute for the self-care and ambulation that the child cannot practice [11, 25]. In our study, the main perceived barrier reported was that exercise took too much time away from family relationships. Due to the consequences such as excessive workload, psychological distress, and reduced social participation of having a child with motor disability, it can lead to restrictions on participation in physical activity in mothers [26]. Other barriers reported in our study were “I am too embarrassed to exercise,” “It costs too much to exercise,” and “My family members do not encourage me to exercise.” This indicates that women with children with disabilities need more encouragement and motivation to engage in exercise. The relatively high scores of our participants obtained from the exercise benefits scale conclude that they had positive opinions about exercise. Despite this, their insufficient participation in physical activity may be caused by the heavy burden of the care of children with motor disability and inadequate support.

In a study investigating the physical activity level of individuals with a disability and their parents, researchers showed that parents’ daily step counts are very low compared to the targeted step counts [27]. The walking scores of mothers with children with motor disabilities were not adequate in our study too. Tahmaz et al. [27] ascribed this result to the fact that a majority of the parents who have children with developmental disabilities are not in active working life and that the level of responsibility required for child care is higher compared to the parents of healthy children. The majority of our study participants consisted of individuals who were not in active working life and reported that they devoted most of the day to child care. In this regard, our findings coincide.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no study investigating to what extent the physical activity level of the mother is affected by the gross motor function level of the children. Therefore, we investigated to what extent the physical activity levels of the mothers were affected according to the GMFCS level of the child with motor disability. Our results revealed that the IPAQ-SF total physical activity score of the mothers of the children with mild motor disability was higher compared to the mothers of the children with moderate-to-severe motor disability. In general, physical activity levels were insufficient in all of our participants. Especially since children with moderate-to-severe motor disabilities do not have the ability to walk independently, ensuring the transfer of children becomes difficult, particularly as the child’s age and body mass index increase. It has been reported in various studies that the physical activity levels of children with motor disability are lower than their typically developing peers from early ages and that as the severity of motor disability increases, their participation in physical activity decreases [28,29,30,31]. We anticipate that this situation may create difficulties for the families of children with moderate-to-severe motor disability, particularly for their mothers as their main caregivers, in their participation in recreational activities. Julius et al. [32] reported that the participation of the mother and the child in physical activity together may lead to an increase in the child’s moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and a decrease in sedentary behaviors. Based on the results of our study, we think that the same effect may occur in the opposite direction. Insufficient participation in physical activity due to the child’s physical disability may also affect the mother.

Limitations

The targeted sample size in our study could not be reached due to the coronavirus pandemic. We suggest that in future studies, physical activity levels should be applied in larger samples using more objective assessment methods.

Conclusion

The results acquired in our study revealed that none of the mothers of the children with motor disabilities participated in adequate physical activity. It was found that the physical activity levels of the mother with children with motor disability differed according to the gross motor function levels of their children, and the physical activity levels of mothers with children with moderate-to-severe motor disability were also lower.

The environmental factors, the disability level of the child with a motor disability, and various personal factors are all more or less effective on the physical activity level of the mothers. It is essential to enhance the health of mothers so they can cope with the psychological and physical burden of having a child with a motor disability. Therefore, it is required to carry out studies to increase the physical activity participation of mothers of children with motor disabilities. Findings from this study may contribute to designing strategies to improve the health outcomes of mothers of children with motor disabilities.

Data availability

Data for this work can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

References

Maenner MJ, Blumberg SJ, Kogan MD et al (2016) Prevalence of cerebral palsy and intellectual disability among children identified in two US National Surveys, 2011–2013. Ann Epidemiol 26(3):222–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.01.001

Houtrow AJ, Larson K, Olson LM et al (2014) Changing trends of childhood disability, 2001–2011. Pediatrics 134(3):530–538. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-0594

Zablotsky B, Black LI, Maenner MJ et al (2019) Prevalence and trends of developmental disabilities among children in the United States: 2009–2017. Pediatrics 144(4):e20190811. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0811

Vonneilich N, Lüdecke D, Kofahl C (2016) The impact of care on family and health-related quality of life of parents with chronically ill and disabled children. Disabil Rehabil 38(8):761–767. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1060267

Miodrag N, Burke M, Tanner-Smith E et al (2015) Adverse health in parents of children with disabilities and chronic health conditions: a meta-analysis using the Parenting Stress Index’s Health Sub-domain. J Intellect Disabil Res 59(3):257–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12135

Gallagher S, Hannigan A (2014) Depression and chronic health conditions in parents of children with and without developmental disabilities: the growing up in Ireland cohort study. Res Dev Disabil 35(2):448–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2013.11.029

King G, Chiarello L (2014) Family-centered care for children with cerebral palsy: conceptual and practical considerations to advance care and practice. J Child Neurol 29(8):1046–1054. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073814533009

Schwellnus H, King G, Baldwin P et al (2020) A solution-focused coaching intervention with children and youth with cerebral palsy to achieve participation-oriented goals. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr 40(4):423–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2020.1711841

Dehghan L, Dalvand H, Hadian MR, Rasanani et al (2021) Exploring the process of health in mothers of children with cerebral palsy: changing “clinical reasoning”. Br J Occup Ther 1-9 https://doi.org/10.1177/03080226211020659

Magaña S, Li H, Miranda E et al (2015) Improving health behaviours of L atina mothers of youths and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res 59(5):397–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12139

Sawyer MG, Bittman M, La Greca AM et al (2011) Time demands of caring for children with cerebral palsy: what are the implications for maternal mental health? Dev Med Child Neurol 53(4):338–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03848.x

Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S et al (2020) World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med 54(24):1451–1462. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955

Karakaş G, Yaman Ç (2017) Examination of the quality of life according to the physical activity status of parents who have disabled individual. J Human Sci 14 (1):724–737. https://doi.org/10.14687/jhs.v14i1.4287

Saglam M, Arikan H, Savci S et al (2010) International physical activity questionnaire: reliability and validity of the Turkish version. Percept Mot Skills 111(1):278–284. https://doi.org/10.2466/06.08.PMS.111.4.278-284

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjorstrom M et al (2003) International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 35(8):1381–1395. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB

Ortabag T, Ceylan S, Akyuz A et al (2010) The validity and reliability of the exercise benefits/barriers scale for Turkish Military nursing students. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation 32(2):55–70. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajrs.v32i2.59297

Sechrist KR, Walker SN, Pender NJ (1987) Development and psychometric evaluation of the exercise benefits/barriers scale. Res Nurs Health 10(6):357–365. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770100603

Palisano RJ (2007) GMFCS-E & R gross motor function classification system: expanded and revised. McMaster University, Canchild centre for childhood disability research

El Ö, Baydar M, Berk H et al (2012) Interobserver reliability of the Turkish version of the expanded and revised gross motor function classification system. Disabil Rehabil 34(12):1030–1033. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2011.632466

Nienhuis CP, Lesser IA (2020) The impact of COVID-19 on women’s physical activity behavior and mental well-being. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(23):9036. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17239036

Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM et al (2018) Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1· 9 million participants. Lancet Glob Health 6(10):e1077–e1086. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30357-7

Pratt M, Varela AR, Salvo D et al (2020) Attacking the pandemic of physical inactivity: what is holding us back? Br J Sports Med 54(13):760–762. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-101392

Tüzün E, Dündar PE (2018) Manisa’da seçilen kentsel ve yarı kentsel aile sağlığı birimlerinde 18–64 yaş arası kadınlarda fiziksel aktivite durumu ve ilişkili faktörle [Physical activity status and related factors in women aged 18–64 in selected urban and semi-urban family health units in Manisa ]. In: 3. International 21. National Public Health Congress

Duygun T, Sezgin N (2003) Zihinsel Engelli ve Sağlıklı Çocuk Annelerinde Stres Belirtileri, Stresle Başaçıkma Tarzları ve Algılanan Sosyal Desteğin Tükenmişlik Düzeyine Olan Etkisi [The effects of stress symptoms, coping styles and perceived social support on burnout level of mentally handicapped and healthy children’s mothers]. Türk Psikoloji Dergisi Türk Psikoloji Dergisi 18(52):37–52

Rassafiani M, Kahjoogh MA, Hosseini A et al (2012) Time use in mothers of children with cerebral palsy: A comparison study. Hong Kong J Occup Ther 22(2):70–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hkjot.2012.11.001

Lee GK, Lopata C, Volker MA et al. (2009) Health-related quality of life of parents of children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 24(4):227–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357609347371

Tahmaz T, Tarakçı D, Tarakçı E (2017) Özel eğitim alan engelli birey ve ailelerinde fiziksel aktivite düzeyinin araştırılması [Investıgatıon of physical activity levels in disabled individuals with special needs education and their families]. Sağlık Bilimleri ve Meslekleri Dergisi 6(2):275–282. https://doi.org/10.17681/hsp.450302

Crytzer TM, Dicianno BE, Kapoor R (2013) Physical activity, exercise, and health-related measures of fitness in adults with spina bifida: a review of the literature. PM&R 5(12):1051–1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.06.010

Levinson L, Reid G (1991) Patterns of physical activity among youngsters with developmental disabilities. CAHPER Journal 57(3):24–28

Anderson DM, Bedini LA, Moreland L (2005) Getting all girls into the game: physically active recreation for girls with disabilities. J Park Recreat Admi 23(4)

Koldoff EA, Holtzclaw BJ (2015) Physical activity among adolescents with cerebral palsy: an integrative review. J Pediatr Nurs 30(5):e105-e117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2015.05.027

Julius BR, O’Shea AM, Francis SL et al (2021) Leading by example: association between mother and child objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behavior. Pediatr Exerc Sci 33(2):49–60. https://doi.org/10.1123/pes.2020-0058

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: RSÖ, ANA; methodology: RSÖ, ANA; formal analysis and investigation: RSÖ; writing —original draft preparation: RSÖ, ANA; writing — review and editing: RSÖ, ANA; resources: RSÖ, ANA; supervision: ANA.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Approval for the study was granted by Ethics Committee of the Non-invasive Clinical Trials of Sivas Cumhuriyet University (Decision number: 2019-10/10, Decision Date: October 9, 2019).

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all the study participants.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Özkan, R.S., Numanoğlu-Akbaş, A. Physical activity and exercise benefits/barriers in mothers of children with motor disabilities. Ir J Med Sci 191, 2147–2154 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02800-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02800-2