Abstract

In recent years, telemedicine has been increasingly incorporated into medical practice, a process which has now been accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. As telemedicine continues to progress, it is necessary for medical institutions to incorporate telemedicine into their curricula, and to provide students with the necessary skills and experience to effectively carry out telemedicine consultations. The purposes of this study are to review the involvement of medical students with telemedicine and to determine both the benefits and the challenges experienced. A literature review on the MEDLINE; CINAHL Plus; APA PsychInfo; Library, Information Science and Technology Abstracts; and Health Business Elite databases was performed on September 7, 2020, yielding 561 results. 33 manuscripts were analysed, with the main benefits and challenges experienced by medical students summarized. In addition to increasing their understanding of the importance of telemedicine and the acquisition of telemedicine-specific skills, students may use telemedicine to act as a valuable workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic. Challenges that students face, such as discomfort with carrying out telemedicine consults and building rapport with patients, may be addressed through the incorporation of telemedicine teaching into the medical curricula through experiential learning. However, other more systemic challenges, such as technical difficulties and cost, need to be examined for the full benefits of telemedicine to be realized. Telemedicine is here to stay and has proven its worth during the COVID-19 pandemic, with medical students embracing its potential in assisting in medical clinics, simulation of clinical placements, and online classrooms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rise in telehealth use in recent years and the current rapid progression of the COVID-19 pandemic, the demand for telemedicine is now greater than ever. Telemedicine, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), is “The delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by all health care professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and for the continuing education of health care providers, all in the interests of advancing the health of individuals and their communities” [33, p. 10]. Telemedicine is likely to continue growing and become more prevalent in medical care, especially due to the pressures placed on the healthcare system by the COVID-19 pandemic [1, 2, 16, 20, 22, 25]. Telemedicine affords many benefits to patients and care providers alike, for example, improved access to care, lower healthcare costs, and reduced risk of infection for both patients and healthcare providers [9, 18, 25, 28]. As medical students progress in their careers, they will undoubtedly encounter telemedicine in their practice. It is therefore necessary for medical students to develop the skillset needed to effectively deliver patient care through telehealth methods. However, there is a lack of telemedicine teaching and learning within the medical school curricula and telehealth delivery opportunities for medical students [22, 29, 30]. Therefore, this paper reviews the medical student experience with telemedicine to determine the various benefits and challenges of involving medical students with telemedicine, with implications on medical curricula development and future healthcare practices. Although telemedicine includes many domains, this paper focuses specifically on telemedicine as a means of healthcare delivery and the incorporation of telemedicine teaching into medical curricula.

Methods

A literature review was performed. This section reports on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as the search strategy.

Study inclusion criteria

All study designs, including clinical studies, review articles, conference abstracts, letters to the editor, and perspectives were included.

-

Participants: This review included medical students in any year and stage of training.

-

Interventions: Articles discussing the delivery of healthcare through telemedicine in any setting and the incorporation of telemedicine teaching and learning in medical school curricula were included. Telephone consultations were also included.

-

Publication date: No time or date restrictions were applied

-

Language: Studies in any language were included.

Study exclusion criteria

Articles that focused on physicians or non-medical students, such as nursing, dental, and veterinary students were excluded. This review also excluded articles that examined application development, continuing medical education, delivery of medical education or examinations, tele-interviews, teleconferences, tele-mentoring, and tele-guidance.

Literature search strategy

The literature search was performed in the Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE); Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL); APA PsychInfo; Library, Information Science and Technology Abstracts; Health Business Elite; and Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE) databases up to September 7, 2020. The search strategy used the following algorithm: (“medical students” OR “medicine students” OR “students in medicine” OR “student doctors”) AND (“telemedicine” OR “telehealth” OR “telecare” OR “telemonitor”).

Results and discussion

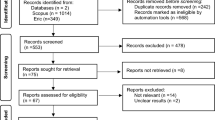

A total of 561 records were obtained, with 164 from MEDLINE, 61 from CINAHL Plus, 52 from APA PsychInfo, 16 from Library, Information Science and Technology Abstracts, 4 from Health Business Elite, and 264 from EMBASE. Figure 1 is a flow diagram of the phases of the review. Following deduplication, 384 records remained for titles and abstracts screening (Fig. 1). After titles and abstracts screening, there were 70 articles left for full-text screening, following which, a total of 33 articles were included in the review for thematic analysis (Fig. 1). The included articles were analysed by two of the authors independently, and the results were reviewed by the third author. Detailed analyses of the benefits and challenges of involving medical students in telemedicine initiatives were performed and the articles were organized into one of three categories:

-

Category 1: Studies evaluating telemedicine theory education with associated clinical telemedicine healthcare delivery (Tables 1 and 2)

-

Category 2: Studies solely evaluating clinical telemedicine healthcare delivery (Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6)

-

Category 3: Studies solely evaluating telemedicine theory education (Tables 7 and 8)

The studies involving medical students in telemedicine initiatives were diverse and spanned studies with fewer than thirty students in educational initiatives [6], to a study with over 3300 students involved with telemedicine practice in a clinical setting [34]. Of the 33 articles included in this review, two experimental design controlled studies were identified [4, 14] (Table 7).

Benefits of involving medical students in telemedicine

Involving medical students in telemedicine resulted in positive outcomes for students, staff, and patients alike. Medical students who participated in telemedicine practice found the experience valuable [1, 7] and reported improved knowledge and understanding of telemedicine [1, 3, 7, 8, 10, 17,18,19, 24, 27, 29]. In the study by Abraham et al., 87% of students strongly agreed that telehealth would be “a valuable service to offer to patients” [1, p. 4]. As well, students gained a better understanding of the use of telemedicine as an adjunct to traditional medical consultations [6], and believed that it would play an important role in their future careers [1, 7, 10, 17, 28]. Jonas et al. found that 80% of surveyed students responded that they would like to incorporate telemedicine into their future practices [17]. By participating in telemedicine curricula, students learned the skills needed to effectively carry out telemedicine consults [1, 3, 17, 20, 21, 24, 27, 29], such as communicating empathy [1, 21] and equipment set-up and use [17, 20]. Moreover, students who attended a virtual class as part of a surgical internship reported higher self-confidence levels in telemedicine-specific communication domains such as exploring patient’s perceptions and concerns [21].

Students who participated in healthcare delivery using telemedicine appreciated the role of telemedicine in various specialties [3, 7, 10, 13, 18, 27], including its use in General Practice [18], Psychiatry [10], Neurology [27], and Ophthalmology [13]. Medical and surgical specialities that currently already utilize telemedicine in their practice, in particular the Primary Care speciality [1, 5, 7, 12, 18, 28, 32], may benefit further from involving students in clinical telemedicine healthcare delivery and telemedicine education initiatives (Table 9).

Telemedicine also provided an opportunity for increased collaboration among students, faculty and staff [3, 8, 11, 18, 19, 27], through opportunities to have more one-on-one time with faculty members [8] and the chance to observe specialists working with general practitioners [18]. Students enjoyed being exposed to a variety of acute and chronic patient cases [1, 3] and having the opportunity to increase their medical knowledge [18, 28]. For example, students learned how to interpret common test results [27] and became familiar with specific management recommendations for skin conditions such as eczema and filariasis [11].

Engaging students in telemedicine also resulted in positive patient outcomes [11, 12, 18, 19, 26, 28, 32]. Through telemedicine, patients could be offered comprehensive care and access to specialists [18, 28]. Telemedicine initiatives may also improve patient self-efficacy, for example, in a study by Schmidt and Sheline, 73% of patients who participated in a student-run “Healthy Living” telehealth coaching program lost weight successfully [26]. Studies by Himstead et al. and Mukundan et al. also reported good patient outcomes with minimal student training [13, 19]. Students developed a deeper understanding of patient barriers in accessing healthcare [26] and social determinants of health [12]. Students acknowledged that telemedicine would be particularly beneficial for vulnerable populations, such as the elderly or those with chronic conditions, as care could be provided in their homes [6]. In Whittemore et al.’s study, patients with diabetes mellitus who participated for three or more months in an insulin titration telemedicine program staffed by medical students, endocrinologists, and educators, were found to have significantly lower HbA1c levels [32].

Challenges of involving medical students in telemedicine

Despite the many benefits that medical students experienced when engaging with telemedicine, there were also challenges. Student-specific challenges included a range of comfort with completing telemedicine visits [1, 4], which may have been due to lack of clinical knowledge and experience [4], and concern about their ability to build rapport and convey empathy [1, 23]. For the latter, students found timely feedback and demonstrations from supervising doctors beneficial in improving their communication skills [1]. Another challenge that frequently arose with telemedicine consults, especially in telephone consults, was the lack of visual impression and ability to perform a physical examination [4, 5, 22, 23]. Moreover, students found it difficult to read patients’ affect [10] and interpret patient distress [21]. In a letter to the editor, fourth-year medical students drew attention to difficulties obtaining full histories from patients when using telemedicine, and that when compared with traditional medical consults, the explanation of diagnoses, treatment, and lifestyle advice was less frequently offered to patients [5]. Students questioned the reliability of information provided by callers [4, 9] and some noted poor patient follow-up [11]. Students from the Medical University of Vienna expressed doubts that telemedicine could enhance the doctor-patient relationship [31]. Another patient concern was privacy and data security [9, 31].

Although telemedicine provided opportunities for learning, Chao et al. described educational barriers such as a lack of exposure to the full scope of practice, difficulties in acquiring procedural skills, and limitations in evaluating students on non-cognitive domains [8].

In terms of environmental challenges, students experienced technical difficulties such as connectivity issues and poor image and sound quality [1, 10, 13, 18, 28]. Although patients often faced challenges with technology, some students enjoyed the educational opportunity to assist patients with using telehealth platforms [1]. There were also cost discrepancies in telemedicine usage [25], with some reporting a fixed upfront cost [11], while others believed telemedicine reduced costs [9, 31].

Telemedicine during COVID-19

Six of the studies were conducted in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in clinical settings [1, 2, 8, 12, 16, 25] and three of these did not include an education component [2, 8, 12].

Students appreciated the opportunity to engage in patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic through telemedicine initiatives [1, 2, 8]. For instance, in one COVID-19 virtual health rotation, medical students provided a valuable workforce in terms of staffing a remote patient monitoring pathway [2]. However, a big challenge was adjusting the number of staff to match demand, as the number of enrolled patients changed over time [2]. Further engaging medical students with this pathway may allow discrepancies to be addressed. The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the delivery of remote clinical education via telemedicine [16], while reducing the risk for COVID-19 transmission [25]. There was also a role for students to help with routine outpatient telemedicine visits during the pandemic [25]. A free clinic run by medical students to serve homeless individuals during COVID-19 saw improved continuity of care that could circumvent lack of access to hospitals and transportation; however, an issue that arose was that homeless patients no longer wanted to continue participating once their health needs were met [12]. In spite of some challenges, telemedicine may offer a safe and viable method for healthcare professionals, including medical students, to continue delivering quality healthcare to patients during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Incorporating telemedicine into medical curricula

Telemedicine has been successfully introduced into medical curricula at a number of institutions worldwide, including in the USA, Switzerland, Brazil, the Czech Republic, and Australia [1, 3, 6,7,8, 10, 14, 15, 17, 18, 20,21,22, 24, 26, 27, 29, 30], and its use should be more widely adopted. There is a large demand for more telemedicine opportunities, with students displaying high interest and support for its incorporation into their learning [7, 15, 34]. To facilitate the development of a telemedicine curricula, medical institutions should consider making improvements to existing programs. For instance, Iancu et al. suggested incorporating telemedicine-specific skills, such as communication that minimizes body motions, functional physical examination skills, and technological literacy, into medical curricula [16]. Pathipati et al. recommended a digital call experience which would allow students to familiarize themselves with remote monitoring tools and participate in consultations [22]. Students who participated in telemedicine programs wished for more clinical experiences [10], such as utilizing telemedicine in clinical practice [30]. They also hoped for more simulation time [29] and greater supervision [11, 25]. This student feedback should be taken into account when developing future curricula. With COVID-19 continuing to disrupt medical education and person-to-person contact, telemedicine provides a feasible alternative to maximize clinical exposure for students and to experience a technology that is here to stay. Medical institutions should capitalize on this opportunity to update medical curricula in keeping with the technological advances occurring in telemedicine and beyond.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this literature review are that there are virtually no limitations to the search criteria, such as being confined to the English language, time period constraints, or restriction in study design. Thus, the depth of experiences conveyed and the perspectives of the students’ themselves are all considered. This study supplements existing literature by identifying and summarizing key benefits and considerations in medical students’ experiences with telemedicine. Limitations of this study include the diversity and heterogeneous nature of the papers necessitating a literature review rather than a systematic review and that the COVID-19 is ongoing, hence, this subject is a rapidly changing landscape.

Conclusion

This literature review summarized medical students’ experiences with telemedicine, in an effort to determine its benefits and challenges. Telemedicine offers a valuable clinical experience for medical students, providing knowledge and skills that they could apply in their future practices. In addition, it provides students with opportunities to collaborate with other faculty and staff, and the ability to continue with clinical learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the benefits, several challenges were also identified, such as difficulty in conveying empathy and problems with technology. However, with medicine becoming increasingly technologized and the COVID-19 pandemic continuing to disrupt medical education, now is the time for medical institutions to consider incorporating telemedicine teaching and learning into the curricula, so that the medical students of today will be prepared for the medical practice of tomorrow.

References

Abraham HN, Opara IN, Dwaihy RL, Acuff C, Brauer B, Nabaty R, Levine DL (2020) Engaging third-year medical students on their internal medicine clerkship in telehealth during COVID-19. Cureus 12(6). https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.8791

Annis T, Pleasants S, Hultman G, Lindemann E, Thompson JA, Billecke S, Badlani S, Melton GB (2020) Rapid implementation of a COVID-19 remote patient monitoring program. J Am Med Inform Assoc 27(8):1326–1330. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa097

de Araújo Novaes M, de Campos Filho AS, Beserra Diniz PR (2019) Improving education of medical students through telehealth. In: The 17th world congress of medical and health informatics. https://doi.org/10.3233/SHTI190712, vol 264, Lyon, pp 1917–1918

Barth J, Ahrens R, Schaufelberger M (2014) Consequences of insecurity in emergency telephone consultations: an experimental study in medical students. Swiss Med Weekly 144:w13,919. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2014.13919

Berwick KL, Applebee L (2020) Replacing face-to-face consultations with telephone consultations in general practice and the concerns this causes medical students. Education for Primary Care: an Official Publication of the Association of Course Organisers, National Association of GP Tutors, World Organisation of Family Doctors, 1–1. https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2020.1786469

Brockes C, Grischott T, Dutkiewicz M, Schmidt-Weitmann S (2017) Evaluation of the education “Clinical Telemedicine/e-Health” in the curriculum of medical students at the university of zurich. Telemed E-Health 23(11):899–904. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2017.0011

Bulik RJ, Shokar GS (2010) Integrating telemedicine instruction into the curriculum: expanding student perspectives of the scope of clinical practice. J Telemed Telecare 16(7):355–358. https://doi.org/10.1258/jtt.2010.090910

Chao TN, Frost AS, Brody RM, Byrnes YM, Cannady SB, Luu NN, Rajasekaran K, Shanti RM, Silberthau KR, Triantafillou V et al (2020) Creation of an interactive virtual surgical rotation for undergraduate medical education during the covid-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ 78(1):346–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.06.039

Chen P, Xiao L, Gou Z, Xiang L, Zhang X, Feng P (2017) Telehealth attitudes and use among medical professionals, medical students and patients in china: A cross-sectional survey. Int J Med Inf 108:13–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.09.009

Dzara K, Sarver J, Bennett JI, Basnet P (2013) Resident and medical student viewpoints on their participation in a telepsychiatry rotation. Acad Psychiatry 37(3):214–216. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.12050101

Greisman L, Nguyen TM, Mann RE, Baganizi M, Jacobson M, Paccione GA, Friedman AJ, Lipoff JB (2015) Feasibility and cost of a medical student proxy-based mobile teledermatology consult service with k isoro, u ganda, and lake a titlán, g uatemala. Int J Dermatol 54(6):685–692. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.12708

Heflin KJ, Gillett L, Alexander A (2020) Lessons from a free clinic during Covid-19: Medical students serving individuals experiencing homelessness using tele-health. J Ambul Care Manage 43(4):308–311. https://doi.org/10.1097/JAC.0000000000000352

Himstead AS, Prasad J, Melucci S, Israelsen P, Gustafson K, Browne A (2020) Telemedicine using a non-mydriatic color fundus camera for retinal imaging in rural panama. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci 61(7):1601–1601

Hindman DJ, Kochis SR, Apfel A, Prudent J, Kumra T, Golden WC, Jung J, Pahwa AK (2020) Improving medical students’ OSCE performance in telehealth: The effects of a telephone medicine curriculum. Acad Med 95(12):1908–1912. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003622

Holubová A, Mužík J, Poláček M, Fiala D, Årsand E, Mužnỳ M, Vlasáková M, Brož J (2018) Improving education of medical students by involving a telemedical system for diabetes into lectures. In: Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics, vol 20, pp A114–A115. Maary Ann Liebert, Inc 140 Huguenot St, 3rd Fl, NEW Rochelle, NY 10801 USA. https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2018.2525.abstracts

Iancu AM, Kemp MT, Alam HB (2020) Unmuting medical students’ education: utilizing telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. J Med Int Res 22(7):e19,667. https://doi.org/10.2196/19667

Jonas CE, Durning SJ, Zebrowski C, Cimino F (2019) An interdisciplinary, multi-institution telehealth course for third-year medical students. Acad Med 94(6):833–837. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002701

Knight P, Bonney A, Teuss G, Guppy M, Lafferre D, Mullan J, Barnett S (2016) Positive clinical outcomes are synergistic with positive educational outcomes when using telehealth consulting in general practice: a mixed-methods study. J Med Int Res 18(2):e31. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4510

Mukundan S Jr, Vydareny K, Vassallo DJ, Irving S, Ogaoga D (2003) Trial telemedicine system for supporting medical students on elective in the developing world. Acad Radiol 10(7):794–797

Naik N, Greenwald P, Hsu H, Harvey K, Clark S, Sharma R, Kang Y, Connolly A (2018) “web-side manner”: A simulation-based, telemedicine communication curriculum. In: Academic emergency medicine. SAEM18 Innovations . https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13433, vol 25, p S298

Newcomb AB, Duval M, Bachman SL, Mohess D, Dort J, Kapadia MR (2020) Building rapport and earning the surgical patient’s trust in the era of social distancing: teaching patient-centered communication during video conference encounters to medical students. J Surg Educ 78(1):336–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.06.018

Pathipati AS, Azad TD, Jethwani K (2016) Telemedical education: training digital natives in telemedicine. J Med Int Res 18(7):e193. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5534

Rallis KS, Allen-Tejerina AM (2020) Tele-oncology in the covid-19 era: are medical students left behind? Trends in Cancer 6(10):811–812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2020.08.001

Rienits H, Teuss G, Bonney A (2016) Teaching telehealth consultation skills. Clin Teach 13(2):119–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12378

Rolak S, Keefe AM, Davidson EL, Aryal P, Parajuli S (2020) Impacts and challenges of United States medical students during the covid-19 pandemic. World J Clin Cases 8(15):3136. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i15.3136

Schmidt S, Sheline E (2018) Yes we can! a self-management curriculum teaching patient self-efficacy can impact patient outcomes in a resource poor, underserved academic primary care setting. In: Journal of general internal medicine. vol 34, pp S866. Wiley 111 River St, Hoboken 07030-5774, NJ USA. https://doi.org/10.1007/11606.1525-1497

Shawagfeh A, Shanina E (2018) Telemedicine clinic for medical students during neurology clerkship: The present and the future. In: Annals of Neurology, vol 84, pp S73–S74. Wiley 111 River St, Hoboken 07030-5774, NJ USA

Vasquez-Cevallos LA, Bobokova J, González-Granda PV, Iniesta JM, Gómez EJ, Hernando ME (2018) Design and technical validation of a telemedicine service for rural healthcare in ecuador. Telemed E-Health 24(7):544–551. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2017.0130

Walker C, Echternacht H, Brophy PD (2019) Model for medical student introductory telemedicine education. Telemed E-Health 25(8):717–723. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2018.0140

Waseh S, Dicker AP (2019) Telemedicine training in undergraduate medical education: Mixed-methods review. JMIR Med Educ 5(1):e12,515. https://doi.org/10.2196/12515. http://mededu.jmir.org/2019/1/e12515/

Wernhart A, Gahbauer S, Haluza D (2019) ehealth and telemedicine: Practices and beliefs among healthcare professionals and medical students at a medical university. PLoS One 14(2):e0213,067. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213067

Whittemore M, Worsham C, McElwee M (2013) Delivering ongoing quality diabetes care to the uninsured using telemedicine. In: Diabetes, vol 62, pp A679–A680. Am Diabetes Assoc. https://doi.org/10.2337/db13-2519-2692

WHO (1998) Group Consultation on Health Telematics: A health telematics policy in support of WHO’s health-for-all strategy for global health development : report of the WHO group consultation on health telematics, 11-16 December, Geneva, 1997. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/63857?locale=ar

Yaghobian S, Ohannessian R, Iampetro T, Riom I, Salles N, de Bustos EM, Moulin T, Mathieu-Fritz A (2020) Knowledge, attitudes and practices of telemedicine education and training of French medical students and residents. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 1357633X20926829. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X20926829

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Royal Academy of Medicine in Ireland (RAMI), and the eHealth section of RAMI, for the opportunity to carry out this research project as part of the RAMI eHealth Section Medical Student Awards 2020.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karlstad University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chelsea Cheng is the recipient of the Royal Academy of Medicine of Ireland, eHealth section student award 2020

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, C., Humphreys, H. & Kane, B. Transition to telehealth. Ir J Med Sci 191, 2405–2422 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02720-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02720-1