Abstract

Objective

This study evaluates correlations between insomnia and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany.

Methods

The internet-based International COVID-19 Sleep Study (ICOSS) questionnaire including sociodemographic questions as well as sleep- and emotion-related scales was distributed in Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic from May 1 to September 30, 2020. Insomnia and mental state were assessed using the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-2), and visual analogue scale. Qualitative analyses of demographic characteristics were performed and correlation analyses of the variables calculated.

Results

A total of 1103 individuals participated and 858 valid questionnaires (70.61% females) were obtained. Mean age and body mass index were 41.97 ± 12.9 years and 26 ± 5.9 kg/m2, respectively. Most participants were married (n = 486, 56.6%), living in the city (n = 646, 75.3%), and white (n = 442, 51.5%). The prevalence of insomnia, anxiety, and depression was 19.5% (ISI > 7), 6.6% (GAD-2 > 3), and 4.8% (PHQ-2 > 3), respectively. Compared to the insomnia group, the mean and median ISI, PHQ‑4, PHQ‑2, and GAD‑2 scores of the non-insomnia group were lower, while their mean and median quality of life and quality of health scores were significantly higher (P < 0.05). Pearson correlation analysis showed a positive correlation between the ISI and PHQ‑2 (r = 0.521, P < 0.001), GAD‑2 (r = 0.483, P < 0.001), and PHQ‑4 scores (r = 0.562, P < 0.001); however, the ISI score negatively correlated with the quality of life (r = −0.490, P < 0.001) and quality of health scores (r = −0.437, P < 0.001).

Conclusion

Insomnia, anxiety, and depression were very prevalent during the pandemic. Anxiety and depression were more severe in the insomnia than in the non-insomnia group, and insomnia and mental health are closely related.

Zusammenfassung

Zielsetzung

Diese Studie untersucht die Zusammenhänge zwischen Schlaflosigkeit und psychischen Gesundheitsfaktoren während der COVID-19-Pandemie in Deutschland.

Methoden

Der internetbasierte Fragebogen der Internationalen COVID-19-Schlafstudie (ICOSS), der auch soziodemographische Fragen sowie schlaf- und emotionsbezogene Skalen enthielt, wurde während der COVID-19-Pandemie vom 1. Mai bis 30. September 2020 in Deutschland verteilt. Schlaflosigkeit und psychischer Zustand wurden mit dem Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), dem Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), der Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-2) und der visuellen Analogskala erfasst. Qualitative Analysen der demographischen Merkmale wurden durchgeführt und Korrelationsanalysen der Variablen berechnet.

Ergebnisse

Insgesamt nahmen 1103 Personen an der Studie teil und 858 gültige Fragebögen (70,61 % Frauen) wurden ausgefüllt. Das Durchschnittsalter der Teilnehmer betrug 41,97 ± 12,9 Jahre, der durchschnittliche Body-Mass-Index 26 ± 5,9 kg/m2. Die meisten Teilnehmer waren verheiratet (n = 486, 56,6 %), lebten in der Stadt (n = 646, 75,3 %) und waren weiß (n = 442, 51,5 %). Unter den Teilnehmern lag die Prävalenz von Schlaflosigkeit, Angst und Depression bei 19,5 % (ISI > 7), 6,6 % (GAD-2 > 3) bzw. 4,8 % (PHQ-2 > 3). Im Vergleich zur Insomniegruppe waren die Mittelwerte und Mediane der ISI-, PHQ-4-, PHQ-2- und GAD-2-Scores der Nichtinsomniegruppe niedriger, während deren Lebensqualitäts- und Gesundheitsqualitätsscores höhere, statistisch signifikante (p < 0,05) Mittelwerte und Mediane aufwiesen. Die Pearson-Korrelationsanalyse zeigte eine positive Korrelation zwischen dem ISI- und PHQ-2-Score (r = 0,521, p < 0,001) sowie dem GAD-2- (r = 0,483, p < 0,001) und PHQ-4-Score (r = 0,562, p < 0,001); der ISI-Score war jedoch negativ korreliert mit dem Lebensqualitäts- (r = −0,490, p < 0,001) und Gesundheitsqualitätsscore (r = −0,437, p < 0,001).

Schlussfolgerung

Schlaflosigkeit, Angstzustände und Depression waren während der Pandemie weit verbreitet. Angstzustände und Depression waren in der Insomniegruppe stärker ausgeprägt als in der Nichtinsomniegruppe; Schlaflosigkeit und psychische Gesundheit sind eng miteinander verbunden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a respiratory disease that is currently considered a global threat for its extreme infectivity and high transmission rate [1]. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 as a pandemic, therefore becoming the first pandemic of this century [2].

The COVID-19 pandemic has not only had a significant impact on individuals, industries, the economy, and health systems, but has also caused unimaginable collateral damage. Since the beginning of the pandemic, a mental health crisis has also followed, and symptoms of anxiety and depression have occurred more frequently [3]. As of writing this article, there have been more than 200 million confirmed cases and over 4.1 million deaths in more than 200 countries, including Germany [4]. In Germany, the first COVID-19 patient was confirmed on January 27, 2020, and the infection quickly spread nationwide [5]. The first wave of COVID-19 in Germany occurred throughout February 2020. On August 19, 2021, the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) demonstrated Germany had started the fourth wave of COVID-19, especially among young people [6]. To reduce the spread of COVID-19, the RKI, the German Federal Government, and the state governments focused on and implemented precautionary measures such as the mandatory use of face masks in public places, extensive COVID-19 screening tests, social distancing, self-quarantine, vaccination, and other measures [7]. However, the incidence of COVID-19 continued to rise and fall, and as of September 6, 2021, the daily number of new confirmed cases was around 5000 [8].

Several studies published on previous epidemics (e.g., severe acute respiratory syndrome, SARS; Ebola) have reported that the massive outbreak increased cases of depression and anxiety among the general public, therefore highlighting the importance of psychiatric assessment and early intervention to decrease susceptibility to mental disorders during an epidemic [9, 10]. COVID-19 is anticipated to have a greater impact on mental health than the previously mentioned epidemics [11].

Insomnia is a clinical disorder characterized by difficulty in falling asleep, difficulty in sleep maintenance, early awakening, and nonrestorative sleep. It exists widely in the general population, and studies from Norway, Britain, and Germany show that the prevalence of insomnia has increased to about 10% of the population in recent years [12,13,14]. At present, the subjective tool for clinical evaluation of insomnia and sleep quality is the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) scale, which has the advantages of simplicity, easy operation, and low time consumption.

The International COVID-19 Sleep Study (ICOSS) is an international collaboration involving a group of sleep experts worldwide who focus on describing the nature and rates of various sleep and circadian rhythm symptoms [15]. Previous studies that made use of the ICOSS questionnaire have shown that participants at high risk of obstructive sleep apnea had increased odds of having COVID-19 and were two times more likely to be hospitalized or treated in intensive care units [16]. Additionally, it was also shown in a study by Morin that insomnia, anxiety, and depression were prevalent during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic [17].

However, to the best of our knowledge, the associations between insomnia and mental health-related factors during the COVID-19 pandemic have not yet been explored in Germany. Hence, as part of an international collaboration, our study aimed to use a cross-sectional design to evaluate correlations between insomnia and mental health-related factors during COVID-19 in Germany.

Methods

Questionnaire

The ICOSS questionnaire is composed of 50 questions with a total of 106 items, including sociodemographic information such as gender, age, height, weight, marital status, living area, educational level, race, occupation, infection with COVID-19, economic impact, and smoking and drinking habits. Moreover, the survey also contains sleep-related and emotion-related scales, including the ISI [18], the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) for Depression and Anxiety [19], the WHO-Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5) [20], and the STOP questionnaire (snoring, tiredness, observed apnea, and high blood pressure) [21].

Insomnia

The ISI scale was specifically designed to evaluate the degree of insomnia. This questionnaire contains seven items, and each item was divided into five levels with 0–4 points per item [18]. The higher the score, the more severe the insomnia. A score of 0–7 points indicates the absence of insomnia; 8–14 points, mild insomnia; 15–21 points, moderate insomnia; and 22–28 points, severe insomnia. Previous reports have shown the reliability and validity of the ISI scale in evaluating insomnia [22]. Similarly, this study reports a relatively high internal consistency of the ISI scale (α = 0.873).

Depression and anxiety

Mental health was assessed using the anxiety and depression scale (PHQ-4), which is a shorter version of the PHQ‑9 scale [23]. This scale includes the first two questions of the PHQ‑2 depression module and the first two questions of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder‑2 (GAD-2) module. Several studies have demonstrated the reliability of PHQ‑2 and GAD‑2 as screening tools [24,25,26,27]. The possible answers for this section are “not at all,” “on certain days,” “on more than half of the days,” and “almost every day,” with values of 0 to 3 assigned to each. The PHQ‑4 scale is evaluated as a sum of the four items, which is a value between 0 and 12. For PHQ‑2 and GAD‑2, a total score > 3 indicates a clinically relevant depression and anxiety disorder [25, 28, 29].

Quality of life and quality of health

Quality of life and quality of health were measured using a 0–100 visual analogue scale.

Participants

From May to September 2020, the questionnaires were collected online through the REDCap software (Version 8.0, Vanderbilt, Nashville, TN, USA) or by distributing physical questionnaires. A total of 1150 subjects completed the questionnaire. We excluded those under the age of 18 years and those with incomplete target data. All participants gave informed consent prior to the survey. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local ethics committee of the Charite University Medicine Berlin (reference number EA1/161/20).

Statistical analysis

Data processing and analysis was performed using SPSS version 23.0 for Mac (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The data were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Normal data were analyzed using Student’s t-test of two independent samples and were described as mean ± standard deviation (x ± s). Non-normal data were described by the median and were analyzed by Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical data were presented as a frequency (N) and percentage (%), and statistical significance was evaluated using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. The correlation between insomnia and mental health-related factors was detected using Pearson correlation. Binary logistic regression was then adopted to explore the risk factors of insomnia and mental health-related problems, and the results were described as the odds ratio (OR) with a confidence interval (CI) of 95%. All data were analyzed using a two-tailed test and a significance level set at P < 0.05.

Results

Comparison of sociodemographic characteristics

The 1103 questionnaires were distributed uniformly, and 858 valid questionnaires (70.61% females) were obtained after excluding those with incomplete scale tests and questionnaires with missing general data. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. Results show that the participants were mostly females (n = 661, 77%) and that the mean age and mean body mass index were 41.97 ± 12.9 years and 26 ± 5.9 kg/m2, respectively. Most of the participants were married (n = 486, 56.6%), living in the city (n = 646, 75.3%), employed (n = 692, 80.7%), and white (n = 442, 51.5%). Among the participants, 15 (1.7%) were diagnosed with COVID-19, 123 participants (14.3%) suffered from “somewhat economic impact,” and 37 (4.3%) suffered from “severe economic impact”; 86 participants (10.0%) were smokers and 301 participants (35.1%) suffered from stress.

According to their ISI scores, participants were assigned to the non-insomnia group (691 cases) or the insomnia group (167 cases). Table 2 shows the demographic data and scale information of the insomnia and non-insomnia groups in Germany. Compared to females of the insomnia group, males of the same group were linked to a greater prevalence of insomnia (36.6 versus 14.5%), and there are significant differences in gender (χ2 = 46.95, P < 0.05) compared with the non-insomnia group. In terms of marital status, the prevalence of insomnia was 18.1% in the single participants, 17.3% in the married participants, and 56.1% in those with other marital statuses. Similarly, there are significant differences in marital status (χ2 = 36.95, P < 0.05) compared with the non-insomnia group. There were also significant differences in education level (χ2 = 33.14, P < 0.05), ethnicity (χ2= 11.57, P < 0.05), employment status (χ2 = 82.31, P < 0.05), financial suffering (χ2 = 45.75, P < 0.05), smoking status (χ2 = 10.46, P < 0.05), and stress levels (χ2 = 113.44, P < 0.05) between the two groups, but the results showed no significant correlations between insomnia and living areas (χ2 = 0.02, P > 0.05) or COVID-19 groups (χ2 = 3.99, P > 0.05).

Comparison of sleep- and emotion-related scales

Among the participants, 19.5% had symptoms of insomnia according to the ISI score (> 7), 6.6% had symptoms of anxiety according to the GAD‑2 score (> 3), and 4.8% had symptoms of depression according to the PHQ‑2 score (> 3) (Table 3).

Comparing the scores of sleep- and emotion-related scales between the two groups, the ISI score, PHQ‑4 score, PHQ‑2 score, and GAD‑2 score of the non-insomnia group had significantly lower mean scores (P < 0.001). On the other hand, the non-insomnia group had significantly higher mean scores in quality of life and quality of health compared with the insomnia group (P < 0.001, Table 4).

Correlations between sleep- and emotion-related scales

The correlations between insomnia (ISI scale), anxiety (GAD‑2 scale), and depression (PHQ‑2 scale) were further analyzed. Pearson correlation analysis showed that there is a positive correlation between the ISI score and the PHQ‑2 score (r = 0.521, P < 0.01), GAD‑2 score (r = 0.483, P < 0.01), and PHQ‑4 score (r = 0.562, P < 0.01). Conversely, the ISI score was negatively correlated with the quality of life score (r = −0.490, P < 0.01) and the quality of health score (r = −0.437, P < 0.01). The detailed results are shown in Table 5.

Logistic regression analysis of insomnia, anxiety, and depression

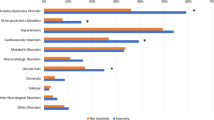

The binary logistic regression method was used for multivariate analysis. The group of participants with ISI score > 7, PHQ‑2 score > 3, and GDA‑2 score > 3 were divided into normal and symptomatic groups as dependent variables, and three logistic regression models were established for each. On the other hand, gender, marital status, living areas, educational level, ethnicity, employment status, financial suffering, smoking, and stress were considered as independent variables, with the last category used as the reference. Table 6 describes the results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis. Findings showed that compared with females, males (OR = 2.59, 95% CI 1.789–3.759, P < 0.001) had a higher risk for developing clinical insomnia. Compared with living in the country, living in the city (OR = 2.40, 95% CI 1.064–5.413, P = 0.035) was observed to be a potential risk factor for depression. Lastly, Asian ethnicity (OR = 3.32, 95% CI 1.056–10.435, P = 0.04) and no smoking (OR = 5.99, 95% CI 1.947–18.377, P = 0.002) were potential risk factors for anxiety.

Discussion

Similar to previous epidemics, the COVID-19 pandemic was foreseen to greatly impact mental health worldwide. In addition, factors such as social environment and one’s health may also contribute to the instability of emotional state, which is one of the susceptibility factors for insomnia [30]. This study conducted an ICOSS survey among the general population in Germany during the COVID-19 outbreak. We utilized different scales to assess overall mental health and the susceptibility of the respondents to insomnia. Moreover, relevant factors were examined to determine the associations between insomnia and mental health-related factors.

The ISI scale has long been proven to have high confidence and validity. The contents of this scale are based on the diagnostic criteria for insomnia in sleep disorders, as stated in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM, 5th ed) [18, 31]. On the other hand, the PHQ‑2 and GAD‑2 scales are widely used in screening for anxiety and depression [23,24,25,26,27]. In this study, the prevalence of insomnia, anxiety, and depression was 19.5% (ISI > 7), 6.6% (GAD-2 > 3), and 4.8% (PHQ-2 > 3), respectively, all of which are a substantial increase compared with the pre-pandemic situation. Before the outbreak, the prevalence of insomnia in Germany was 5.7%, with females two times more likely to develop insomnia than males [32]. A recent meta-analysis summarizing the prevalence of anxiety and depression in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic reported prevalence rates of 31.9% (95% CI, 27.5–36.7) and 33.7% (95% CI, 27.5–40.6), respectively [33]. As seen in the demographic characteristics (Table 2), males are more likely to develop insomnia than females. In this study, the proportion of males with insomnia was higher than that of females. This is inconsistent with several studies showing that severe insomnia is more prevalent in females [34]. Those who are living alone after divorce or separation, are unemployed, have a bachelor’s degree or higher education level, have higher stress levels, have high economic losses, and with no prior COVID-19 infection comprised the majority of the insomnia group. Similarly, several studies have also found that severe insomnia was more prevalent among those who are unemployed, those living alone after divorce or separation, and those living in large cities [35,36,37].

However, this study is of cross-sectional design, and no causal relationship can be inferred from any factor. The results of this study showed that insomnia is closely related to mental health, and that insomnia, anxiety, and depression were very prevalent during the pandemic. With that, we emphasize the importance of emotional stability and psychological counseling to reduce the incidence of sleep diseases.

There are several limitations of this study: (i) the sample size is limited and does not fully represent the German public; (ii) the survey was conducted online, was voluntary, and was influenced by the use of electronic devices and other tools; and (iii) there was a deviation in the number of samples recovered as well as in the distribution of age and occupation. In the future, researchers should expand the sample size, increase the number of variables in the questionnaire, and carry out follow-up studies. Although many factors have already been found to affect the public’s sleep quality during the pandemic, it is still necessary to conduct this research in different countries and at different timepoints. High-quality randomized controlled trials are highly recommended to verify the efficacy of different intervention methods on improving sleep quality. At present, ICOSS research has been carried out in 14 countries, and the second version of the survey will cover more questions, thereby providing more comprehensive data for comparative research.

Conclusion

Our study found that in Germany, insomnia, anxiety, and depression were very prevalent during the pandemic time. Anxiety and depression in the insomnia group were more severe than in the non-insomnia group. Moreover, it was also observed that insomnia and mental health are associated with gender, ethnicity, and employment status. Therefore, medical intervention is warranted to decrease the risks of mental health disorders during the pandemic.

Change history

11 July 2022

An Erratum to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11818-022-00360-w

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- GAD‑2:

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder two-item score

- ICOSS:

-

International COVID-19 Sleep Study

- ISI:

-

Insomnia Severity Index

- PHQ:

-

The Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression and Anxiety

- RKI:

-

Robert Koch Institute

- WHO‑5:

-

World Health Organization-Five Well-Being Index

References

Anderson RM et al (2020) How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet 395(10228):931–934

WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19–11 March 2020. [accessed on 11 November 2021]; 2021 Available from https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 .

Li J et al (2020) The effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on depression, anxiety, and stress in patients with COVID-19: a randomized controlled trial. Front Psychiatry 11:580827

World Health Organization (2021) https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. Accessed 8 Sept 2021

The Robert Koch Institute (2021) https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Situationsberichte/2020-03-04-en.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. Accessed 21 Sept 2021

Deutsche Welle (2021) Germany enters 4th coronavirus wave. https://www.dw.com/en/germany-enters-4th-coronavirus-wave/a-58914201 (Created 20 Aug 2021). Accessed 8 Sept 2021

Kayrouz R et al (2021) A review and clinical practice guideline for health professionals working with indigenous and culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) populations during COVID-19. Front Public Health 9:584000

The Robert Koch Institute (2021) https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Situationsberichte/Sept_2021/2021-09-06-en.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (Created 21 Sept 2021). Accessed: 21 Sept 2021

Jalloh MF et al (2018) Impact of Ebola experiences and risk perceptions on mental health in Sierra Leone, July 2015. BMJ Glob Health 3(2):e000471. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000471

Peng EY et al (2010) Population-based post-crisis psychological distress: an example from the SARS outbreak in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc 109(7):524–532

Piltch-Loeb R, Merdjanoff A, Meltzer G (2021) Anticipated mental health consequences of COVID-19 in a nationally-representative sample: context, coverage, and economic consequences. Prev Med 145:106441–106441

Riemann D et al (2017) European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res 26(6):675–700

Pallesen S et al (2014) A 10-year trend of insomnia prevalence in the adult Norwegian population. Sleep Med 15(2):173–179

Calem M et al (2012) Increased prevalence of insomnia and changes in hypnotics use in england over 15 years: analysis of the 1993, 2000, and 2007 national psychiatric morbidity surveys. Sleep 35(3):377–384

Partinen M et al (2021) Sleep and circadian problems during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: the International COVID-19 Sleep Study (ICOSS). J Sleep Res 30(1):e13206

Chung F et al (2021) The association between high risk of sleep apnea, comorbidities, and risk of COVID-19: a population-based international harmonized study. Sleep Breath 25(2):849–860

Morin CM et al (2021) Insomnia, anxiety, and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: an international collaborative study. Sleep Med 87:38–45

Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM (2001) Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med 2(4):297–307

Löwe B et al (2010) A 4‑item measure of depression and anxiety: validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire‑4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J Affect Disord 122(1–2):86–95

Kittel-Schneider S et al (2020) Prevalence of prediabetes and diabetes mellitus type II in bipolar disorder. Front Psychiatry 11:314–314

Chung F et al (2008) STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology 108(5):812–821

Fernandez-Mendoza J et al (2012) The Spanish version of the insomnia severity index: a confirmatory factor analysis. Sleep Med 13(2):207–210

Kroenke K et al (2009) An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ–4. Psychosomatics 50(6):613–621

Kessler RC et al (2002) Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 32(6):959–976

Plummer F et al (2016) Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD‑7 and GAD-2: a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 39:24–31

Mitchell AJ et al (2016) Case finding and screening clinical utility of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ‑9 and PHQ-2) for depression in primary care: a diagnostic meta-analysis of 40 studies. BJPsych open 2(2):127–138

Staples LG et al (2019) Psychometric properties and clinical utility of brief measures of depression, anxiety, and general distress: the PHQ‑2, GAD‑2, and K‑6. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 56:13–18

Richardson LP et al (2010) Evaluation of the PHQ‑2 as a brief screen for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics 125(5):e1097–e1103

Kroenke K et al (2007) Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med 146(5):317–325

Harvey AG (2011) Sleep and circadian functioning: critical mechanisms in the mood disorders? Annu Rev Clin Psychol 7:297–319

American Psychiatric Association (1980) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders vol 3. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC

Schlack R et al (2013) Häufigkeit und Verteilung von Schlafproblemen und Insomnie in der deutschen Erwachsenenbevölkerung. Robert Koch-Institut, Epidemiologie und Gesundheitsberichterstattung

Salari N et al (2020) Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health 16(1):57

Voitsidis P et al (2020) Insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic in a Greek population. Psychiatry Res 289:113076

Zhou P et al (2021) Investigation on the influencing factors of mental health of healthcare workers for aid in Hubei during the outbreak of COVID-19. Ann Work Expo Health 65(7):833–842

Kim DM et al (2021) The prevalence of depression, anxiety and associated factors among the general public during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 36(29):e214

Hajak G (2001) Epidemiology of severe insomnia and its consequences in Germany. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 251(2):49–56

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Y. Huang, I. Fietze, and T. Penzel declare that they have no competing interests.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local ethics committee of the Charite University Medicine Berlin (reference number EA1/161/20). All participants gave informed consent prior to the survey.

Additional information

Scan QR code & read article online

The original online version of this article was revised: The name of the author Thomas Penzel has been corrected.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Y., Fietze, I. & Penzel, T. Analysis of the correlations between insomnia and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. Somnologie 26, 89–97 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11818-022-00347-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11818-022-00347-7