Abstract

Purpose

Adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET) increases sexual health challenges for women with early-stage breast cancer. Black women are more likely than women of other racial/ethnic groups to report adverse symptoms and least likely to initiate and maintain AET. Little is known about how sexual health challenges influence patient-clinician communication and treatment adherence. This study explores facilitators of and barriers to patient-clinician communication about sexual health and how those factors might affect AET adherence among Black women with early-stage breast cancer.

Methods

We conducted 32 semi-structured, in-depth interviews among Black women with early-stage breast cancer in the U.S. Mid-South region. Participants completed an online questionnaire prior to interviews. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results

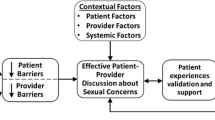

Participants’ median age was 59 (range 40–78 years, SD = 9.0). Adverse sexual symptoms hindered participants’ AET adherence. Facilitators of patient-clinician communication about sexual health included female clinicians and peer support. Barriers included perceptions of male oncologists’ disinterest in Black women’s sexual health, perceptions of male oncologists’ biased beliefs about sexual activity among older Black women, cultural norms of sexual silence among Southern Black women, and medical mistrust.

Conclusions

Adverse sexual symptoms and poor patient-clinician communication about sexual health contribute to lower AET adherence among Black women with early-stage breast cancer. New interventions using peer support models and female clinicians trained to discuss sexual health could ameliorate communication barriers and improve treatment adherence.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Black women with early-stage breast cancer in the U.S. Mid-South may require additional resources to address sociocultural and psychosocial implications of cancer survivorship to enable candid discussions with oncologists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Gradishar WJ, Moran MS, Abraham J, Aft R, Agnese D, Allison KH, et al. Breast cancer, version 3.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2022;20(6):691–722.

van Hellemond IEG, Geurts SME, Tjan-Heijnen VCG. Current status of extended adjuvant endocrine therapy in early stage breast cancer. Curr Treat Options in Oncol. 2018;19(5):26.

Jing L, Zhang C, Li W, Jin F, Wang A. Incidence and severity of sexual dysfunction among women with breast cancer: a meta-analysis based on female sexual function index. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(4):1171–80.

Lambert LK, Balneaves LG, Howard AF, Gotay CC. Patient-reported factors associated with adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy after breast cancer: an integrative review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;167(3):615–33.

Sheppard VB, Sutton AL, Hurtado-de-Mendoza A, He J, Dahman B, Edmonds MC, et al. Race and patient-reported symptoms in adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy: a report from the women’s hormonal initiation and persistence study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2021;30(4):699–709.

Toivonen KI, Williamson TM, Carlson LE, Walker LM, Campbell TS. Potentially modifiable factors associated with adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy among breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Cancers (Basel). 2020;13(1):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13010107.

Hershman DL, Shao T, Kushi LH, Buono D, Tsai WY, Fehrenbacher L, et al. Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126(2):529–37.

Wheeler SB, Spencer J, Pinheiro LC, Murphy CC, Earp JA, Carey L, et al. Endocrine therapy nonadherence and discontinuation in Black and White women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(5):498–508.

Hu X, Walker MS, Stepanski E, Kaplan CM, Martin MY, Vidal GA, et al. Racial differences in patient-reported symptoms and adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy among women with early-stage, hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(8):e2225485.

Reeder-Hayes KE, Troester MA, Wheeler SB. Adherence to endocrine therapy and racial outcome disparities in breast cancer. Oncologist. 2021;26(11):910–5.

Lewis PE, Sheng M, Rhodes MM, Jackson KE, Schover LR. Psychosocial concerns of young African American breast cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012;30(2):168–84.

Shaw LK, Sherman K, Fitness J. Dating concerns among women with breast cancer or with genetic breast cancer susceptibility: a review and meta-synthesis. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9(4):491–505.

Male DA, Fergus KD, Cullen K. Sexual identity after breast cancer: sexuality, body image, and relationship repercussions. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2016;10(1):66–74.

Southard NZ, Keller J. The importance of assessing sexuality: a patient perspective. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13(2):213–7.

Ussher JM, Perz J, Gilbert E, Wong WK, Mason C, Hobbs K, et al. Talking about sex after cancer: a discourse analytic study of health care professional accounts of sexual communication with patients. Psychol Health. 2013;28(12):1370–90.

Hershman DL, Kushi LH, Shao T, Buono D, Kershenbaum A, Tsai WY, et al. Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(27):4120–8.

Kimmick G, Anderson R, Camacho F, Bhosle M, Hwang W, Balkrishnan R. Adjuvant hormonal therapy use among insured, low-income women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(21):3445–51.

Khosla A, Desai D, Singhal S, Sawhney A, Potdar R. Racial and regional disparities in deaths in breast cancer. Med Oncol. 2023;40(7):210.

Moore JX, Royston KJ, Langston ME, Griffin R, Hidalgo B, Wang HE, et al. Mapping hot spots of breast cancer mortality in the United States: place matters for Blacks and Hispanics. Cancer Causes Control. 2018;29(8):737–50.

Kamen C, Jabson JM, Mustian KM, Boehmer U. Minority stress, psychosocial resources, and psychological distress among sexual minority breast cancer survivors. Health Psychol. 2017;36(6):529–37.

Anderson JN, Graff JC, Krukowski RA, Schwartzberg L, Vidal GA, Waters TM, et al. “Nobody will tell you. You’ve got to ask!”: an examination of patient-provider communication needs and preferences among Black and White women with early-stage breast cancer. Health Commun. 2021;36(11):1331–42.

Reese JB, Sorice K, Beach MC, Porter LS, Tulsky JA, Daly MB, et al. Patient-provider communication about sexual concerns in cancer: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(2):175–88.

Zhang X, Sherman L, Foster M. Patients’ and providers’ perspectives on sexual health discussion in the United States: a scoping review. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(11):2205–13.

Turner K, Samuel CA, Donovan HA, Beckjord E, Cardy A, Dew MA, et al. Provider perspectives on patient-provider communication for adjuvant endocrine therapy symptom management. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(4):1055–61.

Carter J, Lacchetti C, Andersen BL, Barton DL, Bolte S, Damast S, et al. Interventions to address sexual problems in people with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Adaptation of Cancer Care Ontario Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(5):492–511.

Hordern A, Street A. Issues of intimacy and sexuality in the face of cancer: the patient perspective. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30(6):E11–8.

Hordern AJ, Street AF. Communicating about patient sexuality and intimacy after cancer: mismatched expectations and unmet needs. Med J Aust. 2007;186(5):224–7.

Politi MC, Clark MA, Armstrong G, McGarry KA, Sciamanna CN. Patient-provider communication about sexual health among unmarried middle-aged and older women. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(4):511–6.

Reese JB, Sorice K, Lepore SJ, Daly MB, Tulsky JA, Beach MC. Patient-clinician communication about sexual health in breast cancer: a mixed-methods analysis of clinic dialogue. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(3):436–42.

Lin JJ, Chao J, Bickell NA, Wisnivesky JP. Patient-provider communication and hormonal therapy side effects in breast cancer survivors. Women Health. 2017;57(8):976–89.

Harrison JD, Young JM, Price MA, Butow PN, Solomon MJ. What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(8):1117–28.

Reese JB, Sorice KA, Pollard W, Zimmaro LA, Beach MC, Handorf E, et al. Understanding sexual help-seeking for women with breast cancer: what distinguishes women who seek help from those who do not? J Sex Med. 2020;17(9):1729–39.

White-Means SI, Osmani AR. Racial and ethnic disparities in patient-provider communication with breast cancer patients: evidence from 2011 MEPS and experiences with cancer supplement. Inquiry. 2017;54:46958017727104.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2003.

Hall JA, Roter DL, Katz NR. Meta-analysis of correlates of provider behavior in medical encounters. Med Care. 1988;26(7):657–75.

Gordon HS, Street RL Jr, Sharf BF, Souchek J. Racial differences in doctors' information-giving and patients’ participation. Cancer. 2006;107(6):1313–20.

Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2084–90.

Li CC, Matthews AK, Aranda F, Patel C, Patel M. Predictors and consequences of negative patient-provider interactions among a sample of African American sexual minority women. LGBT Health. 2015;2(2):140–6.

Kelly-Brown J, Palmer Kelly E, Obeng-Gyasi S, Chen JC, Pawlik TM. Intersectionality in cancer care: a systematic review of current research and future directions. Psychooncology. 2022;31(5):705–16.

Feldman-Stewart D, Brundage MD, Tishelman C, Team SC. A conceptual framework for patient-professional communication: an application to the cancer context. Psychooncology. 2005;14(10):801–9. discussion 10-1

Hill Collins P, Bilge S. Intersectionality. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press; 2016.

Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 1991;43(6):1241–99.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57.

hooks B. Feminist theory: from margin to center. Cambridge, MA: South End Press; 1984.

Holmes AGD. Researcher positionality—a consideration of its influence and place in qualitative research—a new researcher guide. Shanlax Int J Educ. 2020;8(4):1–10.

Anderson JN, Krukowski RA, Paladino AJ, Graff JC, Schwartzberg L, Curry AN, Vidal GA, Jones TN, Waters TM, Graetz I. THRIVE intervention development: using participatory action research principles to guide a mHealth app-based intervention to improve oncology care. J Hosp Manag Health Policy. 2021;5:5. https://doi.org/10.21037/jhmhp-20-103.

Feldman-Stewart D, Brundage MD. A conceptual framework for patient-provider communication: a tool in the PRO research tool box. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(1):109–14.

Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality-an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1267–73.

Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1893–907.

Sandelowski M. Theoretical saturation. In: Given LM, editor. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008. p. 875–6.

Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers, vol. xi. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd; 2009. p. 223. xi

Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16(1):1609406917733847.

Lee MJ, Reddy K, Chowdhury J, Kumar N, Clark PA, Ndao P, et al. Overcoming the legacy of mistrust: African Americans’ mistrust of medical profession. 2018.

Bickell NA, Weidmann J, Fei K, Lin JJ, Leventhal H. Underuse of breast cancer adjuvant treatment: patient knowledge, beliefs, and medical mistrust. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(31):5160–7.

Sutton AL, He J, Edmonds MC, Sheppard VB. Medical mistrust in Black breast cancer patients: acknowledging the roles of the trustor and the trustee. J Cancer Educ. 2019;34(3):600–7.

Palmer Kelly E, McGee J, Obeng-Gyasi S, Herbert C, Azap R, Abbas A, et al. Marginalized patient identities and the patient-physician relationship in the cancer care context: a systematic scoping review. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(12):7195–207.

Moon Z, Moss-Morris R, Hunter MS, Carlisle S, Hughes LD. Barriers and facilitators of adjuvant hormone therapy adherence and persistence in women with breast cancer: a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:305–22.

Dyer K, das Nair R. Why don’t healthcare professionals talk about sex? A systematic review of recent qualitative studies conducted in the United kingdom. J Sex Med. 2013;10(11):2658–70.

Horne S, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. The female sexual subjectivity inventory: development and validation of a multidimensional inventory for late adolescents and emerging adults. Psychol Women Q. 2006;30(2):125–38.

Kohlberger B, Simon VA, Rivera Z. A dyadic perspective on sexual subjectivity and romantic relationship functioning. J Relatsh Res. 2019;10:e22. https://doi.org/10.1017/jrr.2019.18.

Dickerson BJ, Rousseau N. Ageism through omission: the obsolescence of Black women’s sexuality. J Afr Am Stud. 2009;13(3):307–24.

Hinchliff S, Gott M. Seeking medical help for sexual concerns in mid- and later life: a review of the literature. J Sex Res. 2011;48(2-3):106–17.

Canzona MR, Garcia D, Fisher CL, Raleigh M, Kalish V, Ledford CJ. Communication about sexual health with breast cancer survivors: variation among patient and provider perspectives. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(11):1814–20.

American Society of Clinical O. The state of cancer care in America, 2017: a report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(4):e353–e94.

Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate medical education, 2014-2015. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2436–54.

Street RL Jr, Gordon H, Haidet P. Physicians’ communication and perceptions of patients: is it how they look, how they talk, or is it just the doctor? Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(3):586–98.

Siu JY. Communicating under medical patriarchy: gendered doctor-patient communication between female patients with overactive bladder and male urologists in Hong Kong. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15:44.

Bertakis KD. The influence of gender on the doctor-patient interaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76(3):356–60.

Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder AM, Nadal KL, et al. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. Am Psychol. 2007;62(4):271–86.

Salisu MA, Dacus JD. Living in a paradox: how older single and widowed black women understand their sexuality. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2021;64(3):303–33.

Clark R. Perceived racism and vascular reactivity in black college women: moderating effects of seeking social support. Health Psychol. 2006;25(1):20–5.

Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):907–15.

Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:126–33.

Stephens DP, Phillips LD. Freaks, gold diggers, divas, and dykes: the sociohistorical development of adolescent African American women’s sexual script. Sex Cult. 2003;7:3–49.

Townes A, Guerra-Reyes L, Murray M, Rosenberg M, Wright B, Long L, et al. ‘Somebody that looks like me’ matters: a qualitative study of black women’s preferences for receiving sexual health services in the USA. Cult Health Sex. 2022;24(1):138–52.

Hine DC. Rape and the inner lives of Black women in the Middle West. Signs. 1989;14(4):912–20.

Stone JR. Cultivating humility and diagnostic openness in clinical judgment. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(10):970–7.

Rosen LT. Mapping out epistemic justice in the clinical space: using narrative techniques to affirm patients as knowers. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2021;16(1):9.

Lin C, Clark R, Tu P, Bosworth HB, Zullig LL. Breast cancer oral anti-cancer medication adherence: a systematic review of psychosocial motivators and barriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;165(2):247–60.

Kroenke CH, Hershman DL, Gomez SL, Adams SR, Eldridge EH, Kwan ML, et al. Personal and clinical social support and adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy among hormone receptor-positive breast cancer patients in an integrated health care system. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;170(3):623–31.

Paladino AJ, Anderson JN, Graff JC, Krukowski RA, Blue R, Jones TN, et al. A qualitative exploration of race-based differences in social support needs of diverse women with breast cancer on adjuvant therapy. Psychooncology. 2019;28(3):570–6.

Haynes-Maslow L, Allicock M, Johnson LS. Peer support preferences among African-American breast cancer survivors and caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(5):1511–7.

Cope DG. Methods and meanings: credibility and trustworthiness of qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(1):89–91.

Morse JM. Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(9):1212–22.

Gilligan T, Coyle N, Frankel RM, Berry DL, Bohlke K, Epstein RM, et al. Patient-clinician communication: American Society of Clinical Oncology Consensus Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(31):3618–32.

Wang LY, Pierdomenico A, Lefkowitz A, Brandt R. Female sexual health training for oncology providers: new applications. Sex Med. 2015;3(3):189–97.

Reese JB, Zimmaro LA, Bober SL, Sorice K, Handorf E, Wittenberg E, et al. Mobile technology-based (mLearning) intervention to enhance breast cancer clinicians’ communication about sexual health: A Pilot Trial. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2021;19(10):1133–40.

Reed L, Bellflower B, Anderson JN, Bowdre TL, Fouquier K, Nellis K, et al. Rethinking nursing education and curriculum using a racial equity lens. J Nurs Educ. 2022;61(8):493–6.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to extend our sincerest gratitude to the breast cancer survivors who participated in this study. We thank each of them for their willingness to share their lived experiences navigating sexual health during breast cancer survivorship. We also thank Ms. Julia Brewer, Ms. Daphne Brown, Mrs. Hiawatha Cullens, Ms. Yolanda Dillard, Mrs. Regenia Dowell, and Ms. Sandra Ford for their active participation on our community advisory council.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (3R01CA218155-01S1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Janeane N. Anderson: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing-Original Draft

Andrew J. Paladino: Software, Investigation, Data curation, Writing-Review & Editing

Ryan Blue: Software, Investigation, Data curation, Writing-Review & Editing

Derek T. Dangerfield, II: Writing-Review & Editing

Susan Eggly: Writing-Review & Editing

Michelle Y. Martin: Writing-Review & Editing

Lee S. Schwartzberg: Writing-Review & Editing

Gregory A. Vidal: Writing-Review & Editing

Ilana Graetz: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing-Review & Editing

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (18-06058-XP IAA).

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Language usage

I/We confirm all patient/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the patient/person(s) described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of the story.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(PDF 504 kb)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Anderson, J.N., Paladino, A.J., Blue, R. et al. Silent suffering: the impact of sexual health challenges on patient-clinician communication and adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy among Black women with early-stage breast cancer. J Cancer Surviv (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01511-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01511-0