Abstract

This paper advances the concept of the entrepreneurial mindset for women entrepreneurs in a developing country. This paper conceptualizes entrepreneurial mindset from a female perspective and explores its impact on individual life, family, and community. We present the Women Entrepreneurship Plus Model (WE-PLUS) framework embedded in the socio-religious context of a developing country and the effectuation theory of entrepreneurship. This culturally sensitive framework helps women develop an entrepreneurial mindset while leveraging their social capital and religious beliefs. This model is applied in a mother’s entrepreneurship course designed for Pakistani mothers. Results indicate that the participants were able to significantly increase their level of entrepreneurial mindset while contributing to the development of their family and the community.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The role mothers play as nation-builders is long-established, having been recognized and referenced since the beginning of humanity (Bornstein and Cote 2004; Sehgal 2019). Women in the nation-building role play an integral part in progressing humankind. Men and women complement and contribute to each other's lives distinctively. According to the Holy book of Islam (Holy Qur’an, 2001, 4:34), men are primarily responsible for earnings and livelihood, while women bear responsibility for nation-building and raising the new generation.

The industrial revolution encouraged women to join the workforce and compete with men, which sparked the mass movement of women entering the West (Morrar et al. 2017). The importance of women’s contribution to family and nation-building was lost in this effort (Hewlett 1986). The economic definitions of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Gross National Product (GNP) did not consider raising children and caring for the family to be an economic activity. As this perspective got inroads to university curriculums, the role of women as homemakers and nation-builders began to be considered a non-economic activity and was disregarded.

This concept had implications throughout the world. Women continued to join the workforce, which led to an unprecedented level of unemployment. Moreover, this phenomenon also began to penetrate the developing world. Pakistan’s population is approximately 49% female, where 60% are less than 30 years of age, and after graduating, many struggle to find employment opportunities (World Population Review 2020). The higher education curriculum fuels this problem as it is designed to produce corporate employees. The ratio of female students in Pakistani universities has crossed the 60% threshold, which has led to an increase in female graduates. This situation has socio-economic repercussions in Pakistan, which has led to a surge in the unemployment rate among the country's youth.

The curriculum and pedagogy lack in facilitating female students to explore their characteristic qualities and entrepreneurial mindset; instead, it prepares them to compete with men for limited jobs. This practice undermines women’s potential and discourages their nurturing role. In 2010, the Institute of Business Administration (IBA), Karachi, created the Center for Entrepreneurial Development (CED) to promote the entrepreneurial mindset among university students (AMAN-Center for Entrepreneurial Development 2020). By 2012, the center began offering various entrepreneurship programs as an outreach initiative for non-traditional students. Initially, the CED faculty used the traditional business plan approach to teach entrepreneurship. Still, they soon after adopted the effectual approach (Sarasvathy 2001) as it was relevant to the Pakistani context and helped participants start with limited funding and available resources. In 2013, the World Bank approached IBA CED to create a nationwide women’s entrepreneurship program. The CED team convinced the World Bank to use an indigenous framework's effectual approach to entrepreneurship. This decision led the CED team to develop and refine the existing model in a country with strong family values and a predominantly Muslim population.

Hundreds of women attended the World Bank-sponsored WomenX program. Successful implementation led the CED to win the coveted Outstanding Specialty Entrepreneurship Program Award from the United States Association for Small Business and Entrepreneurship (USASBE) in 2017 and 2021.

After completing the WomenX Program, the CED team identified a new niche of skilled, qualified, and passionate mothers. These mothers had less time but were keen on developing an entrepreneurial mindset to contribute to their family and community.

The new framework titled Women Entrepreneurship Plus model (WE-PLUS) was introduced in a new program, called the ‘Mothers Entrepreneurship Program," in 2019. Hundreds of women participants have attended this program since its inception. The WE-PLUS model has proven relevant to the Pakistani context as it helps women in multiple ways. The effectuation modules assist participants in discovering their hidden potential, leading to higher self-efficacy to act entrepreneurially. The family orientation and nation-building module enable them to look beyond self and contribute towards family and nation-building and further relate themselves to the contributions made by leading women mentioned in various Abrahamic religions. This program obtained unprecedented results; women, mothers, and homemakers were encouraged to tap into their entrepreneurial potential and engage in multiple entrepreneurial and nation-building activities.

This research attempts to propose a new construct, i.e., entrepreneurial mindset for women and mothers, referred to as ‘WE-PLUS’ derived from the key learnings of Abrahamic religions and effectuation theory. This paper further describes the application of the WE-PLUS model in the Pakistani context and investigates the impact on Pakistani women’s lives, families, and surroundings.

The following section contains a literature review on developing an entrepreneurial mindset concept in the context of Effectuation and Abrahamic religions. Following this, the ‘Methods’ section elaborates on the experiment designed to test the WE-PLUS model. Various constructs used to test the model are described. A mixed-method approach is used to test the impact of this model on the participants of the Mother’s Entrepreneurship program at IBA Karachi. The results and discussion section analyze the WE-PLUS model’s capability to develop an entrepreneurial mindset through the program. The paper concludes with its contribution to this area and policy implications.

2 Literature Review

The content of entrepreneurship programs can be classified into three categories: basics of business basics in new venture creation, core entrepreneurial content, and the entrepreneurial mindset (Kuratko et al. 2017). Business basics dominate the entrepreneurship course content because teaching is often left to business faculty. More attention is needed in developing core entrepreneurship content, emphasizing the entrepreneurial mindset and its application to one's personal and professional life.

The term ‘entrepreneurial mindset’ has garnered worldwide attention in recent years. An entrepreneurial mindset extends beyond entrepreneurship itself; it is the ability to recognize and pursue opportunities by leveraging one’s resources (McGrath and Macmillan 2000). Ireland et al. (2003) define the mindset as the ability to quickly identify and act on opportunity and assemble resources even under uncertain circumstances. Haynie et al. (2010) define it as the ability to sense, act, and mobilize under uncertain conditions. McGrath and MacMillan (2000) further conceptualize the entrepreneurial mindset as a way of thinking and acting with the discipline of a habitual entrepreneur. Kuratko and Morris (2017) view the entrepreneurial mindset as possessing certain attitudinal and behavioral aspects. They view entrepreneurship not as a mechanical phenomenon of opportunity, discovery, exploitation, and business plan formation, but rather as embodying empowerment and transformation, thinking “big” and challenging the status quo, working within affordable loss, and leveraging surprises (Sarasvathy 2001; Kuratko and Morris 2017; Welsh, 2014). Further, it encompasses opportunity alertness, resource leveraging, value innovation, passion, persistence and tenacity, creative problem solving, optimism, vision, adaptation, resilience, change, risk mitigation, guerrilla behavior, and viewing failure as a learning opportunity. The entrepreneurial mindset has a broad scope and covers applying entrepreneurship principles in the individual's personal and professional life.

2.1 Entrepreneurial Mindset for Women and Mothers

Entrepreneurship has garnered widespread attention in the last decade. This attention has led to the subject's popularity among researchers and policymakers for employment generation and economic revival. Despite this, the current understanding of entrepreneurship has created two significant challenges (Korsgaard 2007). The first challenge is the growth perspective, which is the understanding that entrepreneurs contribute to the growth of national economies. This perspective has led to the belief that the primary purpose of entrepreneurship is new venture creation, growth, and job creation (Wiklund 2003). Therefore, growth means development and becomes the criterion on which entrepreneurs are judged. Non-growth business models lack interest and are generally disregarded. The growth perspective does not allow for appreciation of the efforts of women entrepreneurs, as they may not be able to generate visible growth in turnover and headcount (Welsh et al. 2018, 2020; Kaciak and Welsh 2020).

This perspective suggests that the concept of growth is based on traditional male standards, which leads to the second challenge: the measurement of women's entrepreneurial contributions. The masculine lens measurement of entrepreneurial success makes it difficult for women to succeed since male-oriented characteristics, strengths, and values are emphasized. Many of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) studies (Revuelto-Taboada et al. 2012) consider the traditional variables, i.e., education, startup skills, fear of failure, networks and entrepreneurial intentions, etc., as drivers of female entrepreneurship. Most entrepreneurial growth has been represented by men, which has shifted the power dynamic in their favor. Bird and Brush (2002) posit that the term ‘entrepreneurship’ is defined by male behavior.

Similarly, Stevenson (1990) states that the theories of entrepreneurship were developed by looking at masculine behavior. Korsgaard (2007) finds a measurement problem with the traditional means of measuring entrepreneurial success. He further posits that the existing measures cannot capture the actual contribution of female entrepreneurs.

The female entrepreneurial mindset takes a unique trajectory. Female entrepreneurship differs as women utilize their idiosyncratic human capital and employ different processes to identify opportunities (Brush 1992). Brush et al. (2009) describe motherhood as the core of women's entrepreneurship and use it as a metaphor to represent the household and the family context. The ‘5M’ framework by Brush (1992) places motherhood at the center. This central position highlights women's critical role and position in the family and symbolizes meaningful gender awareness. According to Jennings and McDougald (2007), the family and household context might influence more women than men. Gender roles (e.g., identification with family roles) become a resource to pursue entrepreneurship (Leung et al. 2010). Leung (2011) cites the motherhood role as an enabling factor for Japanese women pursuing the entrepreneurial journey.

Female entrepreneurs are motivated to help others (Brush 1992) and concern their community and society. Women are socially oriented and help each other in education, child-rearing, resource sharing, and network development (Nel et al. 2010). Female entrepreneurs are concerned about balancing work and life (Sendra-Pons et al., 2021). They integrate motherhood and entrepreneurship to add value to their family and community and further leverage it beyond pure wealth creation (e.g., gaining respect, satisfaction, sense of achievement, quality time with family) (Rosa et al. 1996; Khurshid & Saba, 2017). A study on Pakistani women entrepreneurs (Khan 2020) in Malakand reports that women's social capital plays a crucial role in the survival and expansion of business as they leverage cross-gender economic networks that do not challenge social norms. Anggadwita et al. (2021) posit that the socio-cultural environment and social perceptions positively and significantly impact the entrepreneurial orientation of Indonesian women entrepreneurs.

The effectuation lens (Sarasvathy 2001) is used in this research to investigate the distinctive qualities of female entrepreneurs. These women use existing resources and substantially reduce risk by collaborating within their network. The action orientation enables them to take small initiatives that result in learning and growth.

2.2 Abrahamic Religions and the Entrepreneurial Mindset

The application of spirituality and religiosity in management has gained recognition in the past decade due to forming a special interest group called Management, Spirituality & Religion (MSR). Religion impacts billions: it not only influences ethics and values but also guides on political, economic, social, legal, and environment-related issues (Gümüsay 2015). The Abrahamic religions, (i.e., Judaism, Christianity, Catholicism, Islam, among others), have a lot regarding management and entrepreneurship. The scriptures from the Abrahamic faiths encourage a life of purpose, humility, hard work, service to others, a metaphysical objective, and a relationship with God. Yost et al. (2019) explain how Christian literature is used to shift a mindset of selfishness and scarcity to selflessness and abundance. Davis (2013) describes the role of religion as an explanatory variable for the entrepreneurial behavior of those who practice Islam. The holy book of Islam, the Quran, regards women highly and emphasizes the importance of their role. The Quranic stories of four mothers are an example of how the Abrahamic religions help us understand the relationship between religion and the entrepreneurial mindset.

The four mothers discussed in this research are Hajirah, the wife of Abraham and mother of Ismail; Asiya, the wife of Pharaoh and the foster mother of Moses; Mary, the mother of Jesus; and Khadija, the wife of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH)Footnote 1) respectively. These mothers possess common characteristics: bravery, creativity, perseverance, resilience, courage, caring, nurturing, long-term perspective beyond oneself and community, futuristic, and concern for the next generation.

The Holy Scripture describes these mothers as women of great purpose, caring, nurturing, and possessing a nation-building orientation. Based on the foundations of this literature, a framework called the Women Entrepreneurship Plus Model (WE-PLUS) is presented.

2.3 The WE-PLUS Model

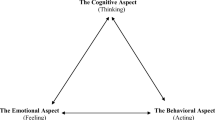

The proposed WE-PLUS model is presented in Fig. 1. An entrepreneurial mindset from the female perspective first emphasizes meaning and purpose, establishing why an individual has been created and their life purpose. This construct encourages the individual to have a high sense of wonder and interpret experiences to enable them to understand and find the best within themselves. In Urdu and Persian poetry, this is referred to as the concept of “Khudi."According to literature, attaining a higher level of Khudi leads to BeKhudi or a sense of service to others (Khaliq 2011).

The second component of the WE-PLUS model comprises the effectuation theory (Sarasvathy and Glinska 2018). Effectuation is the creative means to pursue small goals within one’s affordable loss. The effectuation principles are organic, easy to comprehend and lead to an action orientation. This concept is called "a bird in the hand," which means assessing one’s identity, background knowledge, and network to achieve effectuation. During this process, the individual is encouraged to introspect and develop partnerships with like-minded individuals.

The third component of the WE-PLUS model is the family orientation. According to the framework, women with strong family orientation play a central role in propelling the success of their families. A strong family orientation enables women entrepreneurs to leverage family members in their pursuits, ultimately benefiting the family.

The final component of the WE-PLUS model is nation-building orientation. This component refers to the pursuit of noble opportunities, which lead to service in the community and beyond. As the female entrepreneur gains experience, she uses her effectual experiences and family orientation in noble pursuits to benefit society. The WE-PLUS mindset leads to exciting outcomes (see Fig. 1). The first outcome is self-efficacy, a mindset of abundance, and an action orientation towards effectually pursuing opportunities. The second outcome describes connectivity with the family, leveraging the family, and making the family win. The third outcome is to look beyond oneself and work to better one’s community and society.

3 Research Methodology

The IBA’s Center for Entrepreneurial Development started the Women Entrepreneurship Program, focusing on helping women and especially mothers, discover their entrepreneurial potential and contribute to the country's socio-economic development. This activity was undertaken as a research project to test the WE-PLUS model developed at IBA CED. The program is offered in two cities, Karachi and Faisalabad. Approximately 250 women participated in the 50-h course over two months. The facilitators explained the WE-PLUS model during the course with the help of case studies, experiential exercises, and guest speaker sessions. The participants had to pay a fee of 60 USD to attend this course and were approached through social media and word-of-mouth marketing.

During the course, various interventions were carried out to help participants understand the four components of the WE-PLUS model, including purpose & meaning, effectuation, family orientation, and nation-building. Pre- and Post-intervention data were collected from the participants in a structured questionnaire on all four constructs. The impact of the intervention is described in the discussion and results section. In the second phase, fifteen women were approached 1 year after the program for a detailed interview on the impact of the interventions on their own lives, their family, and their community. These women were selected based on convenience sampling. Saturation occurred after twelve participants were interviewed. A brief description of the participants is presented in Table 1 (see Appendix).

A mixed methodology design is used in this research. This design includes both qualitative and quantitative research approaches (Brannen 2017). The model proposed in this research has four constructs: purpose and meaning, effectuation, nation-building, and family orientation. An extensive analysis of the four components is described in the following section:

3.1 Meaning and Purpose (Pre-effectuation)

The purpose and meaning construct comprises four sub-constructs: a sense of purpose, sense of wonder, finding one’s best self, or ‘Khudi,’ and sense of service, 'BeKhudi'. The sense of purpose construct is built on the Quranic principles and the explanation of Iqbal (Khaliq 2011). The sense of wonder construct is also built on the Quranic injunction to ponder nature and the things happening around oneself. Christensen et al. (2012) state that the yardstick with which God will measure one’s life is not dollars, but how individuals helped others become better human beings.

Every person is a manifestation of the creator and created in a unique and idiosyncratic manner with limitless creativity (Khaliq 2011). They possess a sense of wonder aids in reflection and creativity, while a sense of purpose and wonder develops self-awareness (Khudi). Khudi is defined as a divine inspiration that every individual possesses (Khaliq 2011). As the level of Khudi rises, the concept of BeKhudi emerges and encourages the individual to be of use to others. Qualitative open-ended questions are developed to ask questions about these constructs.

The purpose construct includes four qualitative questions to test the participants’ meaning and purpose. These questions inquire on the individual's drive, how that purpose has developed during the program, how the training helped recognize potential skills and abilities, and how the knowledge gained will be implemented.

3.2 Effectuation

Effectuation is a way of thinking which contributes to the entrepreneur’s identification of opportunities and innovation (Fisher 2012). It is a set of decision-making principles that help entrepreneurs in their choices in times of uncertainty (Fisher 2012). Causation was observed to be the opposite of effectuation (Reymen et al. 2017; Villani et al. 2018). Effectuation emphasizes the creative use of the resources at hand. In casual thinking, the decision-maker makes the decision first and then employs their skills to find the resources as a means to its ends. Sarasvathy further builds upon effectuation with five core principles to use. These are a bird in the hand, affordable loss, quilt, lemonade, and pilot in the plane principle (Read et al. 2016). The role of effectuation is of crucial importance in nation-building, family orientation, and business growth. Women should be encouraged to recognize their ‘bird in hand’ while pursuing entrepreneurship. The crazy quilt principle of effectuation elucidates the concept of self-selected partners. The women can make collaborations by engaging their family members in their businesses. Ten questions test the effectual mindset of the women in the planning, adaptability, vision, and effectual entrepreneurial mindset test (PAVE), developed by Read et al. (2016). The PAVE test tests the planning, adaptability, vision, and effectual entrepreneurial mindsets. A pre-and post-training PAVE test is conducted on the participants.

3.3 Family Orientation

Family orientation and entrepreneurship have a strong association (Lindvert et al. 2017). Women are part of family businesses across the globe (Dugan et al. 2016). These women engage their families to launch entrepreneurial ventures (Edelman et al. 2016). In our proposed model, incorporating effectual reasoning helps women engage their families to assist them in their entrepreneurial journey. The family orientation constructs developed by Rasheed et al. in 2018 are used to measure the family orientation of the participants.

The family orientation construct consists of the following four sub-constructs: family centered (FC), family centered cum self-centered (FCSC), self-centered cum family centered (SCFC), and self-centered (SC) (Qureshi et al. 2019; Rasheed et al. 2018). Family centered and self-centered exist on either end of a spectrum, while the remaining two occur in the middle. The participants are asked to distribute ten points over the four answer options, where a higher score indicates greater agreement. Reference values from previous use of this scale are used to benchmark family orientation.

3.4 Nation-Building

The concept of nation-building was first proposed by Hippler (2005). Women serve as nation-builders and play a key role in society by raising children, nourishing their skills, and leading them to become better individuals (Duflo 2012). The WE-PLUS model proposes that mothers change culture by leaning into their distinctive nature. Developing women’s unique entrepreneurial abilities can help socio-economic development. The Rasheed et al. (2018) and Qureshi et al. (2019) nation-building construct is used to measure the nation-building orientation of the participants.

The nation-building construct has four sub-constructs: nation-building (NB), nation-building cum self-centered (NBSC), self-centered cum nation-building (SCNB), and self-centered (SC) (Qureshi et al. 2019; Rasheed et al. 2018). This tool demonstrates the role of women as nation-builders and their contributions to society. The nation-building role is tested in the context of entrepreneurship. The participants are asked to distribute ten points over four answer options, where a higher score indicates greater agreement.

4 Results and Discussion

Data collected through the PAVE test and orientation questionnaires have been analyzed with SPSS software. Statistical analysis has been performed through the application of paired sample t-tests. The p-values have been calculated, and the results are presented below:

4.1 Meaning and Purpose (Pre-effectuation)

Women entrepreneurs were encouraged to create unique entrepreneurial ventures with available resources to pursue their meaning and purpose. The WE-PLUS model describes the four components of the purpose and meaning construct (Pre-Effectuation): a sense of purpose, sense of wonder, finding the best within one's self (Khudi), and sense of service (BeKhudi). An interview was conducted to inquire about participants' understanding of the four components.

Twelve interviews were conducted via Zoom virtual meeting technology. Participants were asked questions to gauge the program's impact on their entrepreneurial journey. The research team analyzed interview transcriptions to identify words and statements related to constructs of the WE-PLUS model (i.e., pre-effectuation, effectuation, family orientation, nation-building). Table 5 (see Appendix) reveals the analysis results from selected participants. The following section describes the results.

4.2 Effectual Mindset

A PAVE test analysis was performed to assess the effectual mindset of the participants. Four hundred questionnaires were distributed, and 258 were returned. Forty-four incomplete questionnaires were discarded, resulting in a response rate of 64.5%. All incomplete questionnaires were discarded. TThe researchers performed a PAVE test analysis twice in Karachi and Faisalabad. The results for each group are indicated in Table 2 (see Appendix).

A paired sample t-test was performed to understand the impact of an effectual mindset on participants. The analysis confirmed a significant difference in the pre-and post-planning constructs (p = 0.000). Around 180 questionnaires were distributed among the Karachi sample, with 160 completed, with a response rate of 80%. The results showed that pre-and post-adaptability constructs have a statistically significant means difference (p = 0.018). They confirmed that the participants’ vision was significantly influenced after the training (p = 0.004). The findings also indicated a significant difference in the effectual mindset of the participants (p = 0.000).

The researchers collected data from 60 participants in Karachi group two, with 58 questionnaires returned and a response rate of nearly 96.7%. The results for pre-and post-planning constructs were statistically significant (p = 0.002). There was no significant difference observed in the pre-and post-adaptability of the group's mindset. The p-value was 0.466, and the mean was − 0.74 (7.80). The analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in the pre-and post-vision pair (p = 0.010) with a mean value of 3.38 (9.78). The analysis affirmed that the effectual mindsets of participants are influenced significantly (p = 0.000) after the training as mean values for pre-and post-effectual mindsets are found to be − 6.79 (13.6).

Forty participants were sampled for the PAVE test in Faisalabad group one, with 70 questionnaires distributed, 40 returned, with a response rate of 57%. Results were mixed; however, the pre-and post-effectuation are significant.

4.3 Family Orientation

A paired sample t-test was performed to understand the family orientation of participants after the course. Results are indicated in Table 3 (see Appendix). In Karachi group one, 150 questionnaires were distributed, with 106 questionnaires returned, resulting in a response rate of 70.7%. All incomplete questionnaires were discarded. The analysis revealed a significant difference in pre-and post- family centered (FC) constructs (p = 0.029), pre-and post-family centered cum self-centered orientation (p = 0.008), and pre-and post-FC (p = 0.002). The training did not result in a significant difference between pre-and post-self-centered orientation, indicated by the p-value of 0.073. However, the training has impacted women's pre-and post-self-centered cum family centered (SCFC) orientation (p = 0.001).

In Karachi group two, data from 56 respondents revealed a statistically significant influence after the training (p = 0.000). The pre-and-post-FCSC were statistically significant with a p-value of 0.000, which significantly impacted the family orientation mindset. Likewise, the third pair, the pre-and post-self-centered construct, revealed a statistically significant value of 0.044. This finding means that self-centeredness was significantly reduced. However, the SCFC does not show a significant change in mindset.

The final cycle, Faisalabad group one, sourced sample data from 38 respondents. The analysis revealed a significant difference between pre-and post-family centered constructs (p = 0.000). The training has made a substantial difference in pre-and post-self-centered (SC) orientation which is indicated by a p-value of 0.002. The pre-and post-family centered self-centered orientation (FCSC) analysis also revealed a significant difference with a p-value of 0.000.

4.4 Nation-Building

Data collected from the three groups were analyzed to assess the nation-building mindset of the participants. A questionnaire was distributed to 250 participants. Two hundred and seven valid responses were received, resulting in a response rate of 82.8%.

A paired sample t-test was performed to understand the nation-building mindset of participants. The results in Table 4 (see Appendix) revealed a significant difference between pre-and post-nation-building (NB) in Karachi group one (p = 0.013). The analysis further revealed a significant difference between pre-and post-nation-building cum self-centered (NBSC) mindset (p = 0.022). The difference between pre-and post-SC is found to be statistically significant as well (p = 0.015). Likewise, the pre- and post-SCNB is statistically significant as 0.001.

Fifty-six valid responses were received in the second cycle of data collection, Karachi group two, with a response rate of 80%. The results were statistically significant in the SCNB pre- and post-pair with a p-value of 0.001.

The third training was carried out in Faisalabad, and the Nation Building test analysis from a sample of 40 participants is shown in the table. A statistically significant difference is found between pre-and post-NB mindsets as 0.000. There is no significant difference in pre-and post-nation-building self-centered (NBSC) mindset. The pre-and post-self-centered mindset with statistically insignificant p-values of 0.76 and 0.437. All the other constructs indicate significant differences with p-values of 0.000.

4.5 Outcomes

This section talks about the first outcome of the WE-PLUS model, i.e., effectual mindset. The program participants were asked to share their entrepreneurial journey. During the interview, all participants expressed experiencing a change within themselves and a learned ability to identify resources using the ‘bird in hand’ concept. They became aware of their ever-expanding bird in hand and leveraged their network.

After the course, the participants were provided reassurances, business/personal life coaching, and mentoring sessions with IBA faculty. The participants also used social media platforms and were continuously invited to guest speaker sessions at IBA. The interviews revealed that the participants understood the concept of a bird in the hand and expanded the idea in their everyday lives after the course. Table 5 (see Appendix) describes how the various participants referred to the usefulness of effectual reasoning in their entrepreneurial journey.

4.5.1 Family Orientation

The WE-PLUS model explains the role of mothers in developing, helping, leveraging, and nurturing the family. A woman has many defined roles in Eastern cultures. They look after their children, support their families, and play a significant part in the development of society. Women enrolled in the Mothers Entrepreneurship Program were trained on the family orientation perspective. These women were exposed to interact with women guest speakers with a high family orientation.

During the in-depth interviews, the participants were asked open-ended questions such as the role of family orientation in their entrepreneurial journey. The detailed story-telling interview revealed that the women were very well aware of the importance of family orientation and engaging, leveraging, and nourishing the family members. They had developed an understanding that a conflict between parents can threaten the child's mental, physical, and emotional development.

The analysis (Table 5) showed that the women, who participated in the course, were better able to support their families. Some women were single mothers, divorced, or working hand-in-hand with their husbands. Most of these women were able to nurture their families better. The interview analysis revealed that these women remembered the case stories taught during the course. A detailed list of examples of family orientation is given in Table 5 (see Appendix).

4.5.2 Nation-Building

After completing the program, participants answered questions designed to gauge their nation-building orientation. Analysis of the interview transcripts revealed that women are engaged in social entrepreneurship and nation-building activities.

5 Conclusion

This paper advances the concept of an entrepreneurial mindset in women entrepreneurship, crosses disciplinary boundaries, and uniquely challenges past conceptualizations. The Women Entrepreneurship Plus model (WE-PLUS) contributes to previous literature on the entrepreneurial mindset and women’s entrepreneurship by presenting a unique indigenous model that helps women capitalize on their distinctive qualities. The WE-PLUS model offers an alternative perspective on women’s entrepreneurship. This perspective elaborates on how women contribute to creating a more accurate framework outside of the traditional growth definition and masculine view of entrepreneurship.

Teachings from Abrahamic religions provide insight into women’s role in entrepreneurship. The historical contributions of Hajirah, Asiya, Mary, and Khadija in nation-building reinforce this perspective. These role models endorse the four components of the WE-PLUS model: purpose and meaning, effectuation, family orientation, and nation-building. The WE-PLUS model helps women build confidence in their entrepreneurial ability by offering an alternative measure of success. The contemporary women's liberation and gender equality movements prepare women to compete with men according to traditional masculine standards of success. While the WE-PLUS model develops a feminine “yardstick” that more accurately measures women's contributions and encourages family orientation and nation-building.

Applying the WE-PLUS model in a non-western country context has offered insights into how each of the four constructs helps develop the entrepreneurial mindset. After completing the program, most women pursued value-added entrepreneurial activities with a purpose and meaning, strong family orientation, and a desire to contribute to nation-building.

The WE-PLUS model has many implications for mothers who aim to use their distinctive capabilities for self-development, family support, and nation-building. In contrast to the traditional women entrepreneurship model, this model has boosted the confidence and helped the mothers to recognize their self-importance and the potential to play a role in nation-building activities. The mothers learned that large investments are not a necessity to pursue mompreneurship, as confirmed by Lindvert et al. (2017). The PAVE test results revealed the development of an entrepreneurial mindset after the course. As part of the analysis of the nation-building and family orientation constructs, it is observed that after learning the WE-PLUS model, mothers could leverage their existing resources to contribute to the development of their family and society. In a country like Pakistan, there is a great need to launch such programs to enhance the importance of women. A replication study is proposed in other parts of the world having similar socio-religious backgrounds. Further in-depth longitudinal research can help answer questions related to the sustainability and growth of these mom entrepreneurial ventures.

Notes

“Peace be upon him.".

References

AMAN-Center for Entrepreneurial Development (2020) About AMAN-CED. https://ced.iba.edu.pk/about.php

Anggadwita G, Ramadani V, Permatasari A, Alamanda DT (2021) Key determinants of women’s entrepreneurial intentions in encouraging social empowerment. Serv Bus 15(2):309–334

Bird B, Brush C (2002) A gendered perspective on organizational creation. Entrep Theory Pract 26:41–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225870202600303

Bornstein MH, Cote LR (2004) Mothers’ parenting cognitions in cultures of origin, acculturating cultures, and cultures of destination. Child Dev 75:221–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00665.x

Brannen J (2017) Mixing methods: qualitative and quantitative research. Routledge, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315248813

Brush EG (1992) Research on women business owners: past trends, a new perspective and future directions. Entrep Theory Pract 16:5–30

Brush CG, de Bruin A, Welter F (2009) A gender-aware framework for women’s entrepreneurship. Int J Gend Entrep 1:8–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/17566260910942318

Christensen CM, Allworth J, Dillon K (2012) How will you measure your life? Harper Business, New York

Davis MK (2013) Entrepreneurship: an Islamic perspective. Int J Entrep Small Bus 20:63–69. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2013.055693

Duflo E (2012) Women empowerment and economic development. J Econ Lit 50:1051–1079. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.50.4.1051

Dugan A, Krone S, LeCouvie K, Pendergast J, Kenyon-Rouvinez D, Schuman AM (2016) A woman’s place: the crucial roles of women in family business. Springer, New York

Edelman LF, Manolova T, Shirokova G, Tsukanova T (2016) The impact of family support on young entrepreneurs’ startup activities. J Bus Venturing 31:428–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.04.003

Fisher G (2012) Effectuation, causation, and bricolage: a behavioral comparison of emerging theories in entrepreneurship research. Entrep Theory Pract 36:1019–1051. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00537.x

Gümüsay AA (2015) Entrepreneurship from an Islamic perspective. J Bus Ethics 130:199–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2223-7

Haynie JM, Shepherd DA, Mosakowski E, Earley PC (2010) A situated metacognitive model of the entrepreneurial mindset. J Bus Venturing 25:217–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.10.001

Hewlett SA (1986) A lesser life: the myth of women’s liberation in America. University of Minnesota Law School, Minneapolis

Hippler J (2005) Nation-building: a key concept for peaceful conflict transformation? Pluto Press, London

Holy Qur'an. (A.Y. Ali, Trans. & T. Griffith, Ed.). (2001). Wordsworth.

Ireland RD, Hitt MA, Sirmon DG (2003) A model of strategic entrepreneurship: the construct and its dimensions. J Manage 29:963–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(03)00086-2

Jennings JE, McDougald MS (2007) Work-family interface experiences and coping strategies: Implications for entrepreneurship research and practice. Acad Manage Rev 32:747–760. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159332

Kaciak E, Welsh DHB (2020) Women entrepreneurs and work-life interface: the impact of sustainable economies on success. J Bus Res 112:281–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.073

Khaliq M (2011) Iqbal’s concepts of self ‘Khudi.’ Res J Hum Soc Sci 2:122–124

Khan MS (2020) Women’s entrepreneurship and social capital: exploring the link between the domestic sphere and the marketplace in Pakistan. Strat Change 29:375–387. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.2336

Korsgaard ST (2007) Mompreneurship as a challenge to the growth ideology of entrepreneurship. Kontur-Tidsskrift for Kulturstudier 16:42–46

Kuratko DF, Morris MH (2017) Examining the future trajectory of entrepreneurship. J Small Bus Manage 56:11–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12364

Khurshid A, Saba, A (2017) Contested womanhood: women’s education and (re)production of gendered norms in rural Pakistani Muslim communities. Discourse: Stud Cult Politics Educ 39(4):550–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2017.1282425

Leung A (2011) Motherhood and entrepreneurship: gender role identity as a resource. Int J Gend Entrep 3:254–264. https://doi.org/10.1108/17566261111169331

Leung A, Zietsma C, Peredo A (2010) Revolution of the middle-class housewives: Identity work as a process for embedded change. Proceedings of the International Conference on Institutional Work.

Lindvert M, Patel PC, Wincent J (2017) Struggling with social capital: Pakistani women micro entrepreneurs’ challenges in acquiring resources. Entrep Region Dev 29(7–8):759–790. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2017.1349190

McGrath RG, MacMillan IC (2000) The entrepreneurial mindset: strategies for continuously creating opportunity in an age of uncertainty. Harvard Business Press, Boston

Morrar R, Arman H, Mousa S (2017) The fourth industrial revolution (Industry 4.0): a social innovation perspective. Technol Innov Manage Rev 7:12–20. https://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1117

Nel P, Maritz A, Thongprovati O (2010) Motherhood and entrepreneurship: the mumpreneur phenomenon. Int J Org Innov 3:6–34

Qureshi S, Mustafa A, Amin M (2019) Administration of indigenous entrepreneurship model on a sample of young entrepreneurs. In: 15th SAMF Management Forum, Challenges of Inclusive Growth and Sustainability: The South Asian Context. Proceedings. pp 33–48. https://doi.org/10.31703/ger.2019(IV-III).04

Rasheed et al (2018) An indigenous women entrepreneurship framework. Int J Women Empower 4:31

Read S, Sarasvathy S, Dew N, Wiltbank R (2016) Effectual entrepreneurship, 2nd edn. Routledge, Abingdon

Revuelto‐Taboada L (2012) A comprehensive understanding of social and sustainable entrepreneurship. Manag Decis 50(4):744–748. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741211220462

Reymen I, Berends H, Oudehand R, Stultiëns R (2017) Decision making for business model development: a process study of effectuation and causation in new technology-based ventures. R&D Manage 47:595–606. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12249

Rosa P, Carter S, Hamilton D (1996) Gender as a determinant of small business performance: insights from a British study. Small Bus Econ 8(6):463–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00390031

Sarasvathy SD (2001) Causation and effectuation: toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Acad Manage Rev 26:243–263. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2001.4378020

Sarasvathy SD, Glinska G (2018) Empowerment through ideas: teaching effectuation in Pakistan. https://ideas.darden.virginia.edu/2018/08/empowerment-through-ideas-teaching-effectuation-in-pakistan/

Sehgal HF (2019) Fatima Jinnah: the nation builder. Def J 23:52–56

Sendra-Pons P, Belarbi-Muñoz S, Garzón D, Mas-Tur A (2021) Cross-country differences in drivers of female necessity entrepreneurship. Serv Bus 16:1–19

Stevenson L (1990) Some methodological problems associated with researching women entrepreneurs. J Bus Ethics 9:439–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00380343

Villani E, Linder C, Grimaldi R (2018) Effectuation and causation in science-based new venture creation: a configurational approach. J Bus Res 83:173–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.10.041

Welsh DHB (2014) Creative cross-disciplinary entrepreneurship: A practical approach. Palgrave-Macmillan, New York

Welsh DHB, Kaciak E, Shamah R (2018) Determinants of women entrepreneurs’ firm performance in a hostile environment. J Bus Res 88:481–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.015

Welsh DHB, Kaciak E, Mehtap S, Pellegrini MM, Caputo A, Ahmed S (2020) The door swings in and out: the impact of family support and country stability on women entrepreneurs’ success in the Arab world. Int Small Bus J 39(7):619–642. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242620952356

Wiklund J, Davidsson P, Delmar F (2003) What do they think and feel about growth? An expectancy-value approach to small business managers’ attitudes toward growth. Entrepr Theory Pract 27:247–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-8520.00014

World Population Review (2020) Pakistan population statistics. https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/pakistan-population

Yost PR, Terrill JR, Chung HH (2019) An economy of abundance: from scarcity to human potential in organizational and university life. J Appl Bus Econ 21:182–200. https://doi.org/10.33423/jabe.v21i7.2554

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Misbah Amin and Jesse Herndon for their assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by SQ and ARK. Both authors contributed to writing the manuscript. DW participated three times in the program, edited and revised the paper, as well as prepared the final submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest or competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Qureshi, S., Welsh, D.H.B. & Khan, A.R. Training mom entrepreneurs in Pakistan: a replication model. Serv Bus 16, 799–823 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-022-00480-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-022-00480-1