Abstract

Background

With continued growth in the older adult population, US federal and state costs for long-term care services are projected to increase. Recent policy changes have shifted funding to home and community-based services (HCBS), but it remains unclear whether HCBS can prevent or delay long-term nursing home placement (NHP).

Methods

We searched MEDLINE (OVID), Sociological Abstracts, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Embase (from inception through September 2018); and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Joanna Briggs Institute Database, AHRQ Evidence-based Practice Center, and VA Evidence Synthesis Program reports (from inception through November 2018) for English-language systematic reviews. We also sought expert referrals. Eligible reviews addressed HCBS for community-dwelling adults with, or at risk of developing, physical and/or cognitive impairments. Two individuals rated quality (using modified AMSTAR 2) and abstracted review characteristics, including definition of NHP and interventions. From a prioritized subset of the highest-quality and most recent reviews, we abstracted intervention effects and strength of evidence (as reported by review authors).

Results

Of 47 eligible reviews, most focused on caregiver support (n = 10), respite care and adult day programs (n = 9), case management (n = 8), and preventive home visits (n = 6). Among 20 prioritized reviews, 12 exclusively included randomized controlled trials, while the rest also included observational studies. Prioritized reviews found no overall benefit or inconsistent effects for caregiver support (n = 2), respite care and adult day programs (n = 3), case management (n = 4), and preventive home visits (n = 2). For caregiver support, case management, and preventive home visits, some reviews highlighted that a few studies of higher-intensity models reduced NHP. Reviews on other interventions (n = 9) generally found a lack of evidence examining NHP.

Discussion

Evidence indicated no benefit or inconsistent effects of HCBS in preventing or delaying NHP. Demonstration of substantial impacts on NHP may require longer-term studies of higher-intensity interventions that can be adapted for a variety of settings.

Registration

PROSPERO # CRD42018116198

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

US federal and state programs fund the majority of long-term services and supports (LTSS), with Medicaid accounting for 71% of government expenditures.1 With continued growth in the older adult population, Medicaid spending on LTSS is projected to reach $154 billion by 2025 and more than $400 billion by 2050.1 In 2015, institutional LTSS, or long-term nursing home care, accounted for 47% of overall Medicaid expenditures on LTSS, a proportion that continues to decrease, in part due to national policies (e.g., Balancing Incentive Program) that aim to shift funds to home and community-based services (HCBS).2 However, there remains substantial uncertainty about the benefits of HCBS for community-dwelling adults with impairments, and concern that moving resources away from institutional LTSS may not lead to improved outcomes.3,4,5,6

Here, we present results from a larger review conducted by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Evidence Synthesis Program (ESP),7 focusing on effects of HCBS in preventing or delaying long-term nursing home placement (NHP) for community-dwelling adults with physical and/or cognitive impairments. VA costs for LTSS for eligible veterans is projected to be $9.8 billion in fiscal year 2020, with over two thirds of these expenditures going to institutional care.8,9 VA policymakers are also interested in increasing use of HCBS to help veterans with impairments remain in community settings;10,11 thus, they sought evidence on whether HCBS can decrease the need for institutional care. To address a diverse set of interventions, and to provide summary effects for specific interventions, we conducted a systematic review of reviews.12 We prioritized the highest-quality and most recently completed reviews for detailed results on individual interventions. We provide qualitative syntheses of these results, highlight gaps in the evidence base, and offer recommendations for future research and policy.

METHODS

The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42018116198).

Conceptual Model and Scope

Collaboratively with VA stakeholders (representatives from VA Choose Home Initiative, Geriatrics and Extended Care, and Caregiver Support Program) and an advisory panel of experts in LTSS research, we developed a conceptual framework to organize the wide range of factors contributing to NHP and constituting the potential targets of interventions. We reviewed existing frameworks that have been applied in past research involving adults with impairments.13,14,15,16 Our framework (Fig. 1) included 3 categories of factors that may interact: (1) needs for care due to physical or cognitive impairment, symptoms, and/or medical treatments; (2) personal and social factors that are resources or barriers to meeting needs; and (3) systems and environmental factors including access and quality of healthcare services and HCBS.

We applied our conceptual framework to formulate key questions, develop search terms, inform eligibility criteria, and determine elements of data abstraction. Given the complex array of factors that likely contribute to NHP for any given individual, we considered a broad range of HCBS, from interventions that sought to change modifiable risk factors (in community or outpatient settings) to programs that substituted services at home (for similar care provided at nursing facilities). Additionally, we considered that characteristics of adults with impairments (and often their caregivers) may impact effectiveness of various interventions.

Key Questions (KQ)

For adults with physical and/or cognitive impairments:

-

KQ1—What is the effectiveness of HCBS for preventing or delaying NHP?

-

KQ2—Which characteristics of participants moderate the effectiveness of interventions in preventing or delaying NHP?

Search Strategy

To balance a very broad scope of diverse interventions with determining effects of specific interventions, we focused on identifying relevant systematic reviews. We searched from inception: MEDLINE, Sociological Abstracts, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Embase (through September 2018), and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Joanna Briggs Institute Database, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Evidence-based Practice Center reports, and VA ESP reports (through November 2018). Search terms included MeSH and free text for adults with impairments (or at high risk of developing impairments), range of HCBS, NHP, and systematic reviews (Appendix Table 1). Our expert advisory panel also provided referrals.

Screening and Selection of Eligible Reviews

Duplicate results were removed and abstracts screened by 2 individuals using DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada). Prespecified eligibility criteria (Appendix Table 2) included systematic reviews on community-dwelling adults with existing, or at risk of developing, impairments; HCBS, such as case management, caregiver support, and respite care; and explicit inclusion of NHP (or similar terms such as “institutionalization”). A preliminary list of HCBS helped guide search strategies, but other relevant interventions emerged and were included during screening and selection. If a review defined “nursing home admissions” as including short-term stays for rehabilitation, it was excluded. Included abstracts underwent full-text review by 2 individuals; eligibility at full-text review required consensus.

Data Abstraction and Quality Assessment

All eligible reviews underwent independent data abstraction by 2 individuals for population characteristics (including country where study was conducted), dates of searches, number and characteristics of included primary studies, definition of NHP, and intervention characteristics.

Two reviewers independently assessed quality using criteria adapted from AMSTAR 217 (Appendix Fig. 1); overall quality was rated as high, medium, or low. Consensus on quality ratings was reached through discussion.

For specific effects on NHP, we selected the highest-quality and most recent eligible systematic reviews for each intervention. For example, we prioritized all 4 high-quality reviews on case management (2 conducted within the past 5 years and 2 published in 2013). From prioritized reviews, we further abstracted meta-analysis results (or qualitative summaries) of effects on NHP, moderation of effects by participant or intervention characteristics, ascertainment of NHP by included studies (abstracted directly from primary studies), quality ratings and strength of evidence (as reported by reviews), and total number of unique primary studies that examined NHP as an outcome.

Data Synthesis

Given heterogeneity in populations and interventions, we undertook a qualitative synthesis.18,19 First, we noted the number of eligible reviews addressing different interventions. To determine intervention categories, we primarily relied on review authors’ descriptions and classifications of interventions. However, we also applied our conceptual framework to highlight when interventions have overlapping targets or components (e.g., case management and caregiver-focused interventions). We then summarized intervention effects abstracted from the prioritized subset of higher-quality, more recent, eligible reviews. We also determined the quantity of evidence underlying prioritized reviews of different interventions (i.e., number of unique primary studies), and described the quality of underlying studies and strength of evidence (as rated by reviews). We addressed KQ2 by summarizing participant characteristics associated with effectiveness of interventions, whether this was determined via quantitative subgroup analyses or qualitative summaries.

RESULTS

Overview of Eligible and Prioritized Systematic Reviews

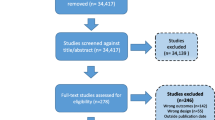

Of 7014 unique citations, 336 articles underwent full-text review and 47 eligible reviews on interventions were identified (Fig. 2). Most eligible reviews addressed older adults and/or those with dementia and evaluated caregiver support (n = 10),20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 respite care and adult day programs (n = 9),30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 case management (n = 8),39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46 or preventive home visits (n = 6)47,48,49,50,51,52 (see Text Box 1 for descriptions of main intervention categories). The remaining reviews53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66 were either very broad in scope (e.g., all nonpharmacologic interventions for dementia) or 1–2 reviews addressing an intervention (e.g., home-based primary care). Most eligible reviews included studies that were conducted in a variety of countries, including USA, Canada, Australia, and high-income countries in Europe and Asia.

Search, selection, and prioritization of eligible systematic reviews. JBI = Johanna Briggs Institute; AHRQ EPC = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Evidence-Based Practice Centers; VA ESP = Department of Veterans Affairs Evidence Synthesis Program. *There were an additional 20 eligible reviews on risk factors for long-term nursing home placement; results on risk factors were described in the larger VA ESP report.†2 reviews—physical activity interventions; 2—home-based primary care; 2—any nonpharmacologic intervention for adults with dementia; 1—any intervention for falls prevention; 1—any intervention for patient or caregiver stress; 1—different settings for personal assistance; 1—in-home health care or personal assistance; 1—assistive technologies; 1—demonstration projects to integrate acute and long-term care in USA and Europe; 1—occupational therapy; and 1—light therapy.

Text Box 1. Major categories of interventions to prevent or delay long-term nursing home placement

Caregiver support—Interventions focused on education, training, and supportive counseling for caregivers. Cognitive reframing is a specific type of counseling that aims to change problematic cognitions (e.g., meaning of disruptive behavior displayed by those with dementia) to help caregivers adopt improved strategies for managing difficult situations. Respite care and adult day programs—Interventions that had a primary or major aim of relieving the burden of daily caregiving tasks. These involved providing a set of services, whether at home, in day clinics, or in residential settings, that partially or fully substituted for care provided by family and other social support. Case management—Interventions involved a variety of components, and some specifically described management of common geriatric syndromes. Case managers had variable professional backgrounds (most commonly nursing), and used a variety of modalities for contact with participants. Most interventions provided education on local resources and coordination of services. Often, interventions also included some caregiver counseling and support. Preventive home visits—In contrast to case management interventions, preventive home visits included older participants (e.g., from population registries) without known impairments or high-risk medical conditions. Interventions differed in number of visits (1 to 12). Nearly all included studies employed health professionals (nurses, physicians, and/or social workers) as visitors. |

For specific intervention effects, we prioritized a total of 20 eligible reviews, including all 15 high-quality reviews.21,27,30, 35,37,41,43,44,46,49,53,55,57,60,66 Characteristics of prioritized reviews are provided in Table 1 and intervention effects are summarized in Table 2 (see Appendix Table 3 for detailed quality ratings and Appendix 4 for detailed results). Overall, prioritized reviews found no benefit or inconsistent effects for caregiver support (2 reviews),21,27 respite care and adult day programs (3 reviews),30,35,37 case management (4 reviews),41,43,44,46 preventive home visits (2 reviews),49,51 and interventions to prevent falls (1 review).53 For caregiver support, case management, and preventive home visits, some reviews highlighted benefits in delaying NHP that were reported by a few studies of each intervention. Prioritized reviews on other interventions, including home-based primary care and physical activity programs, generally found a lack of studies examining NHP as an outcome.54,55,57,60,62,63,64,66 We provide more information below on effects of caregiver support, respite care and adult day programs, case management, and preventive home visits.

Caregiver Support

Two high-quality prioritized reviews21,27 focused on caregiver interventions, included only RCTs, and collectively identified 7 studies that addressed NHP. One review27 specifically evaluated cognitive reframing for caregivers of adults with dementia, but was unable to identify trials that reported effects on NHP (despite aiming to examine NHP). The other review, conducted by VA ESP,21,67 evaluated diverse interventions for caregivers of adults with dementia or cancer, and found 7 trials which examined NHP.68,69,70,71,72,73,74 All studies focused on caregivers of adults with dementia, and review authors reported that these interventions “did not consistently improve…institutionalization for patients with memory-related disorders.”19 However, authors highlighted results from 2 studies that showed delays in NHP; both studies evaluated the same high-intensity model of caregiver support, including 6 tailored in-person counseling sessions over the first 4 months, and ad hoc contacts by counselors via different modalities throughout the follow-up period.70,74 Review authors rated low strength of evidence for all patient outcomes, including institutionalization.

Respite Care and Adult Day Programs

Three high-quality reviews28,33,35 examined respite care and/or adult day programs, and together identified 22 unique studies. The first review included only RCTs and focused on adult day programs for individuals with a variety of different medical conditions;30 quantitative meta-analysis using data from 13 trials75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87 found no overall benefit for decreasing institutionalization (pooled OR 0.84 [95% CI 0.58, 1.21]) or by different comparators (e.g., OR 0.91 [95% CI 0.70, 1.19] for day program vs. comprehensive geriatric care). Review authors reported “the quality of the body of evidence to be low for … death or institutional care…” The second review examined respite care for adults with dementia in any setting (e.g., at home or at day clinics) and identified only one RCT;35 this trial showed more days (i.e., a combined outcome of not experiencing institutionalization or death) for the intervention group.88 The third review included both RCTs and observational studies of respite care in any setting for adults with a variety of conditions.37 This review identified one RCT,89 4 “quasi-experimental” studies (nonrandomized prospective studies with any comparative control),90,91,92,93 and 3 observational cohort studies (without comparators)94,95,96 that evaluated NHP. Review authors conducted meta-analysis using data from 3 quasi-experimental studies,90,91,92 and found increased NHP in the respite care groups (OR 1.79 [95% CI 1.02, 3.12]). However, review authors reported that the 3 cohort studies94,95,96 showed “some support for the benefits of respite care…” Review authors did not indicate overall strength of evidence but noted the role of unmeasured confounders in contributing to these inconsistent results.

Case Management

Four prioritized high-quality reviews41,43,44,46 included 28 unique studies that evaluated effects of case management on NHP. Two reviews focused on adults with dementia,43,44 included only RCTs, and collectively identified 22 unique trials that reported NHP outcomes. One of these reviews43 conducted meta-analyses of data from 9 trials,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105 stratifying by follow-up interval; there were lower odds of NHP with case management at 6 months (OR 0.82 [95% CI 0.69, 0.98]) and 18 months (OR 0.25 [95% CI 0.10, 0.60]), but not at 10–12 months (OR 0.95 [95% CI 0.83, 1.08]) or 24 months (OR 1.03 [95% CI 0.52, 2.03]). Review authors assessed the strength of evidence as low. The second review44 pooled data for NHP from 16 studies69,71,72,73,89,97,101,102,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113 and reported “no statistically significant effect of dementia [case management] compared to usual care” (risk ratio [RR] 0.94 [95% CI 0.85, 1.03]). Additionally, meta-analysis using data on time to NHP from 5 studies69,73,89,110,111 found no statistically significant difference for case management compared with control (weighted mean difference 78.0 days [95% CI − 70.5, 226.1]). Review authors did not provide an assessment of overall strength of evidence.

Two additional reviews addressed older adults with various health conditions and included observational studies in addition to RCTs.41,46 One of these reviews46 found 10 studies that evaluated NHP for adults with dementia74,97,99,100,101,102,105,114,115,116 and 2 that focused on frailty or multimorbidity.117,118 Due to substantial heterogeneity of studies, review authors provided qualitative syntheses. For dementia, programs lasting 2 years or less did not “confer clinically important delays in time to nursing home placement…” (moderate strength of evidence), but those participants “who have in-home spouse caregivers and continue services for longer than 2 years” may benefit from delayed NHP (low strength of evidence). For adults with frailty or multimorbidity, case management did not decrease NHP (low strength of evidence). The other review41 addressed a high-intensity, time-limited case management intervention oriented towards optimizing function, termed “reablement,” for older adults. This review identified only one trial that reported NHP; this trial found no difference in NHP between intervention and control groups.119

Preventive Home Visits

Two prioritized reviews examined preventive home visits and collectively identified 32 unique studies evaluating NHP.49,51 A medium-quality review51 conducted quantitative meta-analysis using data from 13 RCTs120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132 and found overall “reduction in the risk of [NHP] was modest and nonsignificant” (RR 0.91 [95% CI 0.76, 1.09]). In stratified analyses by number of visits (over follow-up of 1–4 years for all studies), interventions with more than 9 visits123,125,127,131 showed an “estimated reduction [of NHP]… 34% (RR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.48–0.92) and the typical risk difference was 2.3%.” Review authors did not report strength of evidence. The other review49 was high quality and included both RCTs and observational studies using “quasi-random methods that approximated the characteristics of randomization”. Quantitative meta-analysis using data from 26 studies117,121,122,124,125,126,127,128,131,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149 showed no overall effect of home visits (RR 1.02 [95% CI 0.88, 1.18]). Stratified analyses found similar results across different follow-up intervals (e.g., RR 0.96 [95% CI 0.69, 1.33] for 8 studies with at least 3 years of follow-up).121,125,127,128,131,134,139,147 Review authors concluded there was “moderate quality evidence of no clinically important difference” between intervention and control.

DISCUSSION

We conducted a systematic review of reviews to examine evidence on interventions that may prevent or delay NHP for adults with, or at risk for, impairments. Caregiver support, respite care and adult day programs, case management, and preventive home visits showed inconsistent effects or no benefit for preventing or delaying NHP. Other interventions, such as home-based primary care and physical activity, had very limited to no evidence to address their effects on NHP.

Existing interventions to support adults with impairments often varied in targeted populations, from participants at earlier stages of chronic conditions to individuals with substantial impairments. While interventions addressing those with less impairments may be able to prevent progression of disability, such programs often require large-scale, long-term investments across a population to see appreciable benefits. In contrast, interventions for adults with substantial care needs will have limited ability to alter trajectories of decline. Current interventions for these individuals have largely sought to improve coordination of services and caregiver support, aiming to bolster informal support networks. However, some individuals with substantial needs do not have social support, and even for those who do, these resources can change quickly and dramatically (e.g., death of a spouse). Our results suggest that many existing interventions help meet the needs of adults with impairments only if there is adequate caregiver support.

Addressing NHP in the USA is made more difficult by fragmentation and complexity of the financial and regulatory environment for healthcare and LTSS. These larger environmental factors make early investment (to reap long-term benefits) not financially viable for many healthcare entities and community organizations. They also shape local access (or lack thereof) to services and limit the potential impact of individual interventions, such as case management, that must work with existing resources. Demonstration projects of new financial benefits or incentives150 must also operate within existing local barriers, including availability and quality of service providers. While changes in state and/or national policies may incentivize improved access and/or higher quality of HCBS,2,151 it will likely take time to change the landscape of local resources.

Evidence Gaps and Future Research

In addition to lack of evidence for certain types of interventions, there was great complexity and variability in multicomponent interventions, such as case management. Additionally, review authors noted that underlying primary studies ranged in participant characteristics and setting. These sources of heterogeneity contributed to challenges in categorizing studies and determining summary results across a body of evidence. In some cases, participants’ low risk for NHP contributed to concerns about inadequate power for detecting intervention effects.

To improve the design and evaluation of complex interventions for adults with impairments, future studies should employ strategies or frameworks that explicitly consider which intervention components may be most appropriate for whom and in which settings.152,153 Applying such strategies to inform selection of intervention components, and to describe whether those components were successfully implemented in particular settings, will facilitate future efforts to summarize and interpret results for complex interventions with similar goals. Therefore, we recommend the following:

-

Randomized evaluations of complex interventions that compare models which differ in only 1–2 key components or setting characteristics (e.g., similar types of services at home vs. in clinic)

-

Randomized evaluations with longer follow-up (likely > 2 years) and larger sample size, particularly for individuals at lower overall risk of NHP

-

Application of strategies and frameworks for selecting components and evaluating implementation of interventions, to inform interpretation of results of complex interventions

Implications for Policy

Due to wide variation in local availability of LTSS,154 coordinating care and services remains a key challenge for adults with impairments and their caregivers.155,156 Therefore, case management may offer other substantial benefits, despite our results suggesting the lack of effectiveness for delaying NHP. Successful case management interventions may need to have relatively high-frequency contacts that are initiated early in the course of chronic conditions (e.g., dementia) and extend for several years. Most US adults with impairments, including veterans, do not have access to this level of longitudinal support and care coordination. Implementing and sustaining such high-intensity case management will require better alignment of LTSS programs at state and federal levels.

Additionally, it remains unclear whether (and which) outcomes are improved with HCBS.5 Some have questioned whether the shift of funding to HCBS (and away from nursing homes) is wise, or if this will lead to worse outcomes for those with substantial needs that cannot be met in community settings.4,6 Our results support concerns that increased utilization of existing HCBS may not lead to appreciable changes in NHP, thus indicating the importance of understanding how HCBS may impact other outcomes. We agree with others who have encouraged policymakers to also consider the value of HCBS for improving patient and family-centered outcomes.3,5

Limitations

We focused on NHP and only included reviews that specified NHP as an outcome of interest. Reviews that exclusively addressed other outcomes, such as quality of life or caregiver burden, were ineligible. Therefore, our findings do not indicate that interventions were not effective for these other outcomes. We relied on review authors’ descriptions of interventions, quality ratings for studies included in reviews, and determination of overall strength of evidence. We also included subgroup analyses reported by reviews, some of which relied on observed characteristics of interventions (e.g., average number of follow-up visits), instead of study design elements. To determine how included studies assessed NHP, we examined primary studies included by prioritized reviews. We found that most studies used participant reports of NHP; few confirmed NHP with additional data sources, such as state or federal administrative data on LTSS utilization. No eligible reviews restricted included studies to only those conducted in the USA, and some studies were conducted > 20 years ago. It may be that evidence from outside the USA is less directly applicable to addressing needs of the US population, but we note that the primary difference between the USA and other high-income countries (that were locations of included studies) is funding of LTSS and not the general availability of various services, whether HCBS or long-term institutional care.157 Older studies may also be less applicable, due to changes in availability of HCBS and growth in assisted living facilities.158

Conclusions

Caregiver support, respite care and adult day programs, case management, and preventive home visits generally do not prevent or delay NHP for adults with (or at risk for) impairments, although a few studies suggested benefit for some higher-intensity models. Demonstration of substantial impacts on NHP may require longer-term studies of high-intensity interventions that can be adapted for a variety of settings.

References

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation Office of Disability. Aging and long-term care policy. 2018.

Medicaid. Balancing Long Term Services & Supports.

Grabowski DC. The cost-effectiveness of noninstitutional long-term care services: review and synthesis of the most recent evidence. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(1):3-28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558705283120

Konetzka RT. The hidden costs of rebalancing long-term care. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(3):771-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12190

Wysocki A, Butler M, Kane RL, Kane RA, Shippee T, Sainfort F. Long-term services and supports for older adults: a review of home and community-based services versus institutional care. J Aging Soc Policy. 2015;27(3):255-79. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2015.1024545

Wysocki A, Kane RL, Golberstein E, Dowd B, Lum T, Shippee T. The association between long-term care setting and potentially preventable hospitalizations among older dual eligibles. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(3):778-97. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12168

Duan-Porter W, Ullman K, Rosebush C, McKenzie L, Ensrud KE, Ratner E, et al. Risk Factors and Interventions to Prevent or Delay Long-Term Nursing Home Placement for Adults with Impairments. VA ESP Project #09-009. 2019.

Colello K, SV. P. Congressional Research Service Report: Long-Term Care Services for Veterans. 2017.

Department of Veterans Affairs. Budget in brief. 2020.

Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans’ families, caregivers, and survivors Federal Advisory Committee planning meeting minutes. October 23-24 2017.

Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Geriatrics and Gerontology Advisory Committee meeting minutes. October 23-24 2017.

Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM, Clarke M. Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1):15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-15

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995:1-10.

Flaskerud JH, Winslow BJ. Conceptualizing vulnerable populations health-related research. Nurs Res. 1998;47(2):69-78.

Lawton MP. Environment and other determinants of weil-being in older people. Gerontologist. 1983;23(4):349-57.

Wahl HW, Iwarsson S, Oswald F. Aging well and the environment: toward an integrative model and research agenda for the future. Gerontologist. 2012;52(3):306-16. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr154

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008

Bearman M, Dawson P. Qualitative synthesis and systematic review in health professions education. Med Educ. 2013;47(3):252-60. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12092

Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. Journal of health services research & policy. 2005;10(1):45-53.

Dickinson C, Dow J, Gibson G, Hayes L, Robalino S, Robinson L. Psychosocial intervention for carers of people with dementia: what components are most effective and when? A systematic review of systematic reviews. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(1):31-43. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610216001447

Griffin JM, Meis LA, Greer N, MacDonald R, Jensen A, Rutks I, et al. Effectiveness of caregiver interventions on patient outcomes in adults with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2015;1:1-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333721415595789

Jensen M, Agbata IN, Canavan M, McCarthy G. Effectiveness of educational interventions for informal caregivers of individuals with dementia residing in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):130-43. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4208

Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Helping caregivers of persons with dementia: which interventions work and how large are their effects? Int Psychogeriatr. 2006;18(4):577-95. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610206003462

Smits CH, de Lange J, Droes RM, Meiland F, Vernooij-Dassen M, Pot AM. Effects of combined intervention programmes for people with dementia living at home and their caregivers: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(12):1181-93. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1805

Vandepitte S, Van Den Noortgate N, Putman K, Verhaeghe S, Faes K, Annemans L. Effectiveness of supporting informal caregivers of people with dementia: a systematic review. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A407-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.961

Van't Leven N, Prick AE, Groenewoud JG, Roelofs PD, de Lange J, Pot AM. Dyadic interventions for community-dwelling people with dementia and their family caregivers: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(10):1581-603. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610213000860

Vernooij-Dassen M, Draskovic I, McCleery J, Downs M. Cognitive reframing for carers of people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011(11):CD005318. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005318.pub2

Goy E, Freeman, M., Kanasagara, D. A systematic evidence review of interventions for non-professional caregivers of individuals with dementia. VA ESP Project #05-225. 2010.

Parker D, Mills S, Abbey J. Effectiveness of interventions that assist caregivers to support people with dementia living in the community: a systematic review. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 2008. p. 137-72.

Brown L, Forster A, Young J, Crocker T, Benham A, Langhorne P, et al. Medical day hospital care for older people versus alternative forms of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(6):CD001730. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001730.pub3

Du Preez J, Millsteed J, Marquis R, Richmond J. The role of adult day services in supporting the occupational participation of people with dementia and their carers: an integrative review. Healthcare (Basel). 2018;6(2):08. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6020043

Ellen MEMBAP, Demaio PBA, Lange AP, Wilson MGP. Adult day center programs and their associated outcomes on clients, caregivers, and the health system: a scoping review. Gerontologist. 2017;57(6).

Fields NL, Anderson KA, Dabelko-Schoeny H. The effectiveness of adult day services for older adults: a review of the literature from 2000 to 2011. J Appl Gerontol. 2014;33(2):130-63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464812443308

Brueckmann A, Seeliger C, Schlembach D, Schleussner E. PP048. Carotid intima-media-thickness in the first trimester as a predictor of preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2013;3(2):84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preghy.2013.04.075

Lee H, Cameron MH. Respite care for people with dementia and their carers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014(1):CD004396.

Mason A, Weatherly H, Spilsbury K, Arksey H, Golder S, Adamson J, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different models of community-based respite care for frail older people and their carers. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11(15):1-157.

Shaw C, McNamara R, Abrams K, Cannings-John R, Hood K, Longo M, et al. Systematic review of respite care in the frail elderly. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(20):1-224. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta13200

Vandepitte S, Van Den Noortgate N, Putman K, Verhaeghe S, Verdonck C, Annemans L. Effectiveness of respite care in supporting informal caregivers of persons with dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(12):1277-88. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4504

Beswick AD, Gooberman-Hill R, Smith A, Wylde V, Ebrahim S. Maintaining independence in older people. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2010;20(2):128-53. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0959259810000079

Berthelsen CB, Kristensson J. The content, dissemination and effects of case management interventions for informal caregivers of older adults: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(5):988-1002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.01.006

Cochrane A, Furlong M, McGilloway S, Molloy DW, Stevenson M, Donnelly M. Time-limited home-care reablement services for maintaining and improving the functional independence of older adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:CD010825. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010825.pub2

Pimouguet C, Lavaud T, Dartigues JF, Helmer C. Dementia case management effectiveness on health care costs and resource utilization: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010;14(8):669-76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-010-0314-4

Reilly S, Miranda-Castillo C, Malouf R, Hoe J, Toot S, Challis D, et al. Case management approaches to home support for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(1):CD008345. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008345.pub2

Tam-Tham H, Cepoiu-Martin M, Ronksley PE, Maxwell CJ, Hemmelgarn BR. Dementia case management and risk of long-term care placement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(9):889-902. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.3906

You EC, Dunt DR, Doyle C. Case managed community aged care: what is the evidence for effects on service use and costs? J Aging Health. 2013;25(7):1204-42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264313499931

Hickam DH, Weiss JW, Guise J-M, Buckley D, Motu'apuaka M, Graham E, et al. Outpatient case management for adults with medical illness and complex care needs. 2013(Prepared by the Oregon Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2007-10057-I.):AHRQ Publication No.13-EHC031-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Elkan R, Kendrick D, Dewey M, Hewitt M, Robinson J, Blair M, et al. Effectiveness of home based support for older people: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2001;323(7315):719-25. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.323.7315.719

Markle-Reid M, Browne G, Weir R, Gafni A, Roberts J, Henderson SR. The effectiveness and efficiency of home-based nursing health promotion for older people: a review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(5):531-69. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558706290941

Mayo-Wilson E, Grant S, Burton J, Parsons A, Underhill K, Montgomery P. Preventive home visits for mortality, morbidity, and institutionalization in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e89257. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089257

Ploeg J, Feightner J, Hutchison B, Patterson C, Sigouin C, Gauld M. Effectiveness of preventive primary care outreach interventions aimed at older people: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can Fam Physician. 2005;51:1244-5.

Stuck AE, Egger M, Hammer A, Minder CE, Beck JC. Home visits to prevent nursing home admission and functional decline in elderly people: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. JAMA. 2002;287(8):1022-8.

van Haastregt JC, Diederiks JP, van Rossum E, de Witte LP, Crebolder HF. Effects of preventive home visits to elderly people living in the community: systematic review. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):754-8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7237.754

Guirguis-Blake JM, Michael YL, Perdue LA, Coppola EL, Beil TL. Interventions to prevent falls in older adults: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319(16):1705-16. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.21962

Steultjens EM, Dekker J, Bouter LM, Jellema S, Bakker EB, van den Ende CH. Occupational therapy for community dwelling elderly people: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2004;33(5):453-60. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afh174

Forbes D, Blake CM, Thiessen EJ, Peacock S, Hawranik P. Light therapy for improving cognition, activities of daily living, sleep, challenging behaviour, and psychiatric disturbances in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014(2):CD003946. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003946.pub4

Wulff KD, Cole DG, Clark RL, Dileonardo R, Leach J, Cooper J, et al. Aberration correction in holographic optical tweezers. Opt Express. 2006;14(9):4170-5.

Montgomery P, Mayo-Wilson E, Dennis J. Personal assistance for older adults (65+) without dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008(1):CD006855. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006855.pub2

Olazaran J, Reisberg B, Clare L, Cruz I, Pena-Casanova J, Del Ser T, et al. Nonpharmacological therapies in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review of efficacy. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;30(2):161-78. https://doi.org/10.1159/000316119

Spijker A, Vernooij-Dassen M, Vasse E, Adang E, Wollersheim H, Grol R, et al. Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions in delaying the institutionalization of patients with dementia: a meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(6):1116-28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01705.x

Van der Roest HG, Wenborn J, Pastink C, Droes RM, Orrell M. Assistive technology for memory support in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017(6):CD009627. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009627.pub2

Gilhooly KJ, Gilhooly ML, Sullivan MP, McIntyre A, Wilson L, Harding E, et al. A meta-review of stress, coping and interventions in dementia and dementia caregiving. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:106. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0280-8

Johri M, Beland F, Bergman H. International experiments in integrated care for the elderly: a synthesis of the evidence. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18(3):222-35. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.819

Frost R, Belk C, Jovicic A, Ricciardi F, Kharicha K, Gardner B, et al. Health promotion interventions for community-dwelling older people with mild or pre-frailty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):157. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0547-8

Gine-Garriga M R-FM, Coll-Planas L, Sitja -Rabert M, & Salva A. Correction. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(1):211-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2017.11.001

Stall N, Nowaczynski M, Sinha SK. Systematic review of outcomes from home-based primary care programs for homebound older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(12):2243-51. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13088

Totten AM, White-Chu EF, Wasson N, Morgan E, Kansagara D, Davis-O'Reilly C, et al. Home-based primary care interventions. 2016(Prepared by the Pacific Northwest Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2012-00014-I.):AHRQ Publication No. 15(6)-EHC036-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Griffin J, Meis L, Carlyle M, Greer N, Jensen A, MacDonald R, et al. Effectiveness of family and caregiver interventions on patient outcomes among adults with cancer or memory-related disorders: a systematic review. VA-ESP Project #09-009. 2013.

Belle SH, Burgio L, Burns R, Coon D, Czaja SJ, Gallagher-Thompson D, et al. Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):727-38.

Brodaty H, Mittelman M, Gibson L, Seeher K, Burns A. The effects of counseling spouse caregivers of people with Alzheimer disease taking donepezil and of country of residence on rates of admission to nursing homes and mortality. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(9):734-43.

Gaugler JE, Reese M, Mittelman MS. Effects of the NYU caregiver intervention-adult child on residential care placement. Gerontologist. 2013;53(6):985-97. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gns193

Teri L, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Buchner DM, Barlow WE, et al. Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(15):2015-22. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.15.2015

Wray LO, Shulan MD, Toseland RW, Freeman KE, Vasquez BE, Gao J. The effect of telephone support groups on costs of care for veterans with dementia. Gerontologist. 2010;50(5):623-31. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnq040

Wright LK, Litaker M, Laraia MT, DeAndrade S. Continuum of care for Alzheimer’s disease: a nurse education and counseling program. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2001;22(3):231-52.

Mittelman MS, Haley WE, Clay OJ, Roth DL. Improving caregiver well-being delays nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(9):1592-9. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000242727.81172.91

Burch S, Longbottom J, McKay M, Borland C, Prevost T. A randomized controlled trial of day hospital and day centre therapy. Clin Rehabil. 1999;13(2):105-12. https://doi.org/10.1191/026921599671803291

Crotty M, Giles LC, Halbert J, Harding J, Miller M. Home versus day rehabilitation: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2008;37(6):628-33. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afn141

Eagle DJ, Guyatt GH, Patterson C, Turpie I, Sackett B, Singer J. Effectiveness of a geriatric day hospital. CMAJ. 1991;144(6):699-704.

Gladman JR, Lincoln NB, Barer DH. A randomised controlled trial of domiciliary and hospital-based rehabilitation for stroke patients after discharge from hospital. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56(9):960-6. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.56.9.960

Hedrick S, Branch L. Adult day health care evaluation study. Med Care. 1993;31:SS1-124.

Hui E, Lum CM, Woo J, Or KH, Kay RL. Outcomes of elderly stroke patients. Day hospital versus conventional medical management. Stroke. 1995;26(9):1616-9.

Masud T, Coupland C, Drummond A, Gladman J, Kendrick D, Sach T, et al. Multifactorial day hospital intervention to reduce falls in high risk older people in primary care: a multi-centre randomised controlled trial [ISRCTN46584556]. Trials. 2006;7(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-7-5

Pitkälä K. The effectiveness of day hospital care on home care patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(9):1086-90.

Tucker MA, Davison JG, Ogle SJ. Day hospital rehabilitation--effectiveness and cost in the elderly: a randomised controlled trial. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;289(6453):1209-12. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.289.6453.1209

Vetter N, Smith A, Sastry D, Tinker G. Day hospital: pilot study report. Research Team for the Care of Elderly People, St Davids Hospital, Department of Geriatrics, 1989.

Weissert W, Wan T, Livieratos B, Katz S. Effects and costs of day-care services for the chronically ill: a randomized experiment. Med Care. 1980;18(6):567-84.

Woodford-Williams E, Mc KJ, Trotter IS, Watson D, Bushby C. The day hospital in the community care of the elderly. Gerontol Clin (Basel). 1962;4(3):241-56.

Young JB, Forster A. The Bradford community stroke trial: results at six months. BMJ. 1992;304(6834):1085-9.

Lawton MP, Brody EM, Saperstein AR. A controlled study of respite service for caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients. Gerontologist. 1989;29(1):8-16. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/29.1.8

Brodaty H, Gresham M, Luscombe G. THE PRINCE HENRY HOSPITAL DEMENTIA CAREGIVERS’TRAINING PROGRAMME. J International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 1997;12(2):183-92.

Conlin MM, Caranasos GJ, Davidson RA. Reduction of caregiver stress by respite care: a pilot study. South Med J. 1992;85(11):1096-100.

Zarit SH, Stephens MAP, Townsend A, Greene R. Stress reduction for family caregivers: effects of adult day care use. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53(5):S267-S77.

Kosloski K, Montgomery RJ, Youngbauer JG. Utilization of respite services: a comparison of users, seekers, and nonseekers. J Appl Gerontol. 2001;20(1):111-32.

Riordan J, Bennett A. An evaluation of an augmented domiciliary service to older people with dementia and their carers. Aging and Mental Health. 1998;2(2):137-43.

Andrew T, Moriarty J, Levin E, Webb S. Outcome of referral to social services departments for people with cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(5):406-14.

Bond MJ, Clark MS. Predictors of the decision to yield care of a person with dementia. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2002;21(2):86-91.

Gaugler JE, Kane RL, Kane RA, Clay T, Newcomer R. Caregiving and institutionalization of cognitively impaired older people: utilizing dynamic predictors of change. Gerontologist. 2003;43(2):219-29. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/43.2.219

Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, Austrom MG, Damush TM, Perkins AJ, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(18):2148-57. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.18.2148

Chien WT, Lee IY. Randomized controlled trial of a dementia care programme for families of home-resided older people with dementia. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(4):774-87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05537.x

Chien WT, Lee YM. A disease management program for families of persons in Hong Kong with dementia. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(4):433-6. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2008.59.4.433

Chu P, Edwards J, Levin R, Thomson J. The use of clinical case management for early stage Alzheimer’s patients and their families. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2000;15(5):284-90.

Eloniemi-Sulkava U, Notkola IL, Hentinen M, Kivela SL, Sivenius J, Sulkava R. Effects of supporting community-living demented patients and their caregivers: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(10):1282-7.

Eloniemi-Sulkava U, Saarenheimo M, Laakkonen ML, Pietila M, Savikko N, Kautiainen H, et al. Family care as collaboration: effectiveness of a multicomponent support program for elderly couples with dementia. Randomized controlled intervention study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(12):2200-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02564.x

Jansen AP, van Hout HP, Nijpels G, Rijmen F, Droes RM, Pot AM, et al. Effectiveness of case management among older adults with early symptoms of dementia and their primary informal caregivers: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(8):933-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.02.004

Lam LC, Lee JS, Chung JC, Lau A, Woo J, Kwok TC. A randomized controlled trial to examine the effectiveness of case management model for community dwelling older persons with mild dementia in Hong Kong. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(4):395-402. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2352

Newcomer R, Yordi C, DuNah R, Fox P, Wilkinson A. Effects of the Medicare Alzheimer’s Disease Demonstration on caregiver burden and depression. Health Serv Res. 1999;34(3):669-89.

Duru OK, Ettner SL, Vassar SD, Chodosh J, Vickrey BG. Cost evaluation of a coordinated care management intervention for dementia. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(8):521-8.

Fortinsky RH, Kulldorff M, Kleppinger A, Kenyon-Pesce L. Dementia care consultation for family caregivers: collaborative model linking an Alzheimer’s association chapter with primary care physicians. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(2):162-70. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860902746160

Gaugler JE, Roth DL, Haley WE, Mittelman MS. Can counseling and support reduce burden and depressive symptoms in caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease during the transition to institutionalization? Results from the New York University caregiver intervention study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56(3):421-8.

Miller R, Newcomer R, Fox P. Effects of the Medicare Alzheimer’s Disease Demonstration on nursing home entry. Health Serv Res. 1999;34(3):691-714.

Mittelman MS, Ferris SH, Shulman E, Steinberg G, Levin B. A family intervention to delay nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;276(21):1725-31.

Mohide EA, Pringle DM, Streiner DL, Gilbert JR, Muir G, Tew M. A randomized trial of family caregiver support in the home management of dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38(4):446-54.

Nobili A, Riva E, Tettamanti M, Lucca U, Liscio M, Petrucci B, et al. The effect of a structured intervention on caregivers of patients with dementia and problem behaviors: a randomized controlled pilot study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2004;18(2):75-82.

Vernooij-Dassen M. Dementia and Homecare: Determinants of the Sense of Competence of Primary Caregivers and the Effect of Professionally Guided Caregiver Support. Lisse, Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger; 1993.

Challis D, von Abendorff R, Brown P, Chesterman J, Hughes J. Care management, dementia care and specialist mental health services: an evaluation. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(4):315-25. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.595

Eggert GM, Zimmer JG, Hall WJ, Friedman B. Case management: a randomized controlled study comparing a neighborhood team and a centralized individual model. Health Serv Res. 1991;26(4):471-507.

Mittelman MS, Brodaty H, Wallen AS, Burns A. A three-country randomized controlled trial of a psychosocial intervention for caregivers combined with pharmacological treatment for patients with Alzheimer disease: effects on caregiver depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(11):893-904. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181898095

Bernabei R, Landi F, Gambassi G, Sgadari A, Zuccala G, Mor V, et al. Randomised trial of impact of model of integrated care and case management for older people living in the community. BMJ. 1998;316(7141):1348-51. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.316.7141.1348

Boult C, Reider L, Leff B, Frick KD, Boyd CM, Wolff JL, et al. The effect of guided care teams on the use of health services: results from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(5):460-6. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.540

Lewin G, De San Miguel K, Knuiman M, Alan J, Boldy D, Hendrie D, et al. A randomised controlled trial of the Home Independence Program, an Australian restorative home-care programme for older adults. Health Soc Care Community. 2013;21(1):69-78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01088.x

Carpenter G, Demopoulos G. Screening the elderly in the community: controlled trial of dependency surveillance using a questionnaire administered by volunteers. BMJ. 1990;300(6734):1253-6.

Gunner-Svensson F, Ipsen J, Olsen J, Waldstrom B. Prevention of relocation of the aged in nursing homes. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1984;2(2):49-56. https://doi.org/10.3109/02813438409017704

Hébert R, Dubois M-F, Wolfson C, Chambers L, Cohen C. Factors associated with long-term institutionalization of older people with dementia: data from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(11):M693-M9.

Hendriksen C, Lund E, Strømgård E. Consequences of assessment and intervention among elderly people: a three year randomised controlled trial. Br Med J. 1984;289(6457):1522-4.

Newbury JW, Marley JE, Beilby JJ. A randomised controlled trial of the outcome of health assessment of people aged 75 years and over. Med J Aust. 2001;175(2):104-7.

Pathy MJ, Bayer A, Harding K, Dibble A. Randomised trial of case finding and surveillance of elderly people at home. The Lancet. 1992;340(8824):890-3.

Sørensen K, Sivertsen J. Follow-up three years after intervention to relieve unmet medical and social needs of old people. Comprehensive gerontology. Section B, Behavioural, social, and applied sciences. 1988;2(2):85-91.

Stuck AE, Aronow HU, Steiner A, Alessi CA, Bula CJ, Gold MN, et al. A trial of annual in-home comprehensive geriatric assessments for elderly people living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(18):1184-9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199511023331805

Stuck AE, Minder CE, Peter-Wüest I, Gillmann G, Egli C, Kesselring A, et al. A randomized trial of in-home visits for disability prevention in community-dwelling older people at low and high risk for nursing home admission. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(7):977-86.

Tinetti ME, Baker DI, McAvay G, Claus EB, Garrett P, Gottschalk M, et al. A multifactorial intervention to reduce the risk of falling among elderly people living in the community. New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;331(13):821-7.

van Haastregt JC, Diederiks JP, van Rossum E, de Witte LP, Voorhoeve PM, Crebolder HF. Effects of a programme of multifactorial home visits on falls and mobility impairments in elderly people at risk: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2000;321(7267):994-8.

van Rossum E, Frederiks CM, Philipsen H, Portengen K, Wiskerke J, Knipschild P. Effects of preventive home visits to elderly people. BMJ. 1993;307(6895):27-32. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.307.6895.27

Vetter NJ, Lewis PA, Ford D. Can health visitors prevent fractures in elderly people? BMJ. 1992;304(6831):888-90.

Bouman A, Van Rossum E, Ambergen T, Kempen G, Knipschild P. Effects of a home visiting program for older people with poor health status: a randomized, clinical trial in the Netherlands: (See editorial comments by Drs. Andreas Stuck and Robert Kane, pp 561–563). Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56(3):397-404.

Byles JE, Tavener M, O'Connell RL, Nair BR, Higginbotham NH, Jackson CL, et al. Randomised controlled trial of health assessments for older Australian veterans and war widows. Med J Aust. 2004;181(4):186-90.

Caplan GA, Williams AJ, Daly B, Abraham K. A randomized, controlled trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment and multidisciplinary intervention after discharge of elderly from the emergency department—the DEED II study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(9):1417-23.

Close J, Ellis M, Hooper R, Glucksman E, Jackson S, Swift C. Prevention of falls in the elderly trial (PROFET): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;353(9147):93-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06119-4

Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, Tu W, Buttar AB, Stump TE, et al. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(22):2623-33. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.22.2623

Dalby DM, Sellors JW, Fraser FD, Fraser C, van Ineveld C, Howard M. Effect of preventive home visits by a nurse on the outcomes of frail elderly people in the community: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2000;162(4):497-500.

Hall N, De Beck P, Johnson D, Mackinnon K, Gutman G, Glick N. Randomized trial of a health promotion program for frail elders. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne du vieillissement. 1992;11(1):72-91.

Hogan DB, MacDonald FA, Betts J, Bricker S, Ebly EM, Delarue B, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a community-based consultation service to prevent falls. CMAJ. 2001;165(5):537-43.

Holland R, Lenaghan E, Harvey I, Smith R, Shepstone L, Lipp A, et al. Does home based medication review keep older people out of hospital? The HOMER randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;330(7486):293.

Kono A, Kai I, Sakato C, Harker JO, Rubenstein LZ. Effect of preventive home visits for ambulatory housebound elders in Japan: a pilot study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2004;16(4):293-9.

Kono A, Kanaya Y, Fujita T, Tsumura C, Kondo T, Kushiyama K, et al. Effects of a preventive home visit program in ambulatory frail older people: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(3):302-9. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glr176

Lenaghan E, Holland R, Brooks A. Home-based medication review in a high risk elderly population in primary care—the POLYMED randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2007;36(3):292-7.

Shapiro A, Taylor M. Effects of a community-based early intervention program on the subjective well-being, institutionalization, and mortality of low-income elders. Gerontologist. 2002;42(3):334-41. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/42.3.334

Sommers LS, Marton KI, Barbaccia JC, Randolph J. Physician, nurse, and social worker collaboration in primary care for chronically ill seniors. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(12):1825-33.

Thomas R, Worrall G, Elgar F, Knight J. Can they keep going on their own? A four-year randomized trial of functional assessments of community residents. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue canadienne du vieillissement. 2007;26(4):379-89.

van Hout HP, Jansen AP, van Marwijk HW, Pronk M, Frijters DF, Nijpels G. Prevention of adverse health trajectories in a vulnerable elderly population through nurse home visits: a randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN05358495]. J Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences Medical Sciences. 2010;65(7):734-42.

Yamada Y, Ikegami N. Preventive home visits for community-dwelling frail elderly people based on Minimum Data Set-Home Care: randomized controlled trial. Geriatrics and Gerontology International. 2003;3(4):236-42.

Kane RA. The noblest experiment of them all: learning from the national channeling evaluation. J Health Services Research. 1988;23(1):189.

Medicaid. Money Follows the Person.

Collins LM, Murphy SA, Nair VN, Strecher VJ. A strategy for optimizing and evaluating behavioral interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30(1):65-73. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm3001_8

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

Geriatrics and Gerontology Advisory Committee. Meeting minutes. September 27-28, 2018.

Veterans Experience Office. Choose home initiative line of action 1 report. June 2018.

Chapter 6-- Family Caregivers’ Interactions with Healthcare and Long-Term Services and Supports National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. In: Schulz R, Eden J, editors. Families Caring for an Aging America. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2016.

Colombo F, Llena-Nozal A, Mercier J, Tjadens F. Help wanted? Providing and paying for long-term care. 2011. OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing; 2011.

Grabowski DC, Stevenson DG, Cornell PY. Assisted living expansion and the market for nursing home care. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(6):2296-315. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01425.x

Funding

This work was supported by VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) funding for ESP (VA-ESP Project No. 09-009; 2019). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations: Results from this evidence review were presented as a poster at the national meeting of the Society for General Internal Medicine in May 2019.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 959 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Duan-Porter, W., Ullman, K., Rosebush, C. et al. Interventions to Prevent or Delay Long-Term Nursing Home Placement for Adults with Impairments—a Systematic Review of Reviews. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 2118–2129 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05568-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05568-5