Abstract

Background

Intensive outpatient programs address the complex medical, social, and behavioral needs of individuals who account for disproportionate healthcare costs. Despite their promise, the impact of these programs is often diminished due to patient engagement challenges (i.e., low rates of patient participation and partnership in care).

Objective

The objective of this study was to identify intensive outpatient program features and strategies that increase high-need patient engagement in these programs.

Design

Qualitative study.

Participants

Twenty program leaders and clinicians from 12 intensive outpatient programs in academic, county, Veterans Affairs, community, and private healthcare settings.

Approach

A questionnaire and semi-structured interviews were used to identify common barriers to patient engagement in intensive outpatient programs and strategies employed by programs to address these challenges. We used content analysis methods to code patient engagement barriers and strategies and to identify program features that facilitate patient engagement.

Key Results

The most common barriers to patient engagement in intensive outpatient programs included physical symptoms/limitations, mental illness, care fragmentation across providers and services, isolation/lack of social support, financial insecurity, and poor social and neighborhood conditions. Patient engagement strategies included concrete services to support communication and use of recommended services, activities to foster patient trust and relationships with program staff, and counseling to build insight and problem-solving capabilities. Program features that were identified as enhancing engagement efforts included: 1) multidisciplinary teams with diverse skills, knowledge, and personalities to facilitate relationship building; 2) adequate staffing and resources to handle the demands of high-need patients; and 3) a philosophy that permitted flexibility and patient-centeredness.

Conclusions

Promising clinical, interpersonal, and population-based approaches to engaging high-need patients frequently deviate from standard practice and require creative and proactive staff with adequate time, resources, and flexibility to address patients’ needs on patients’ terms.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, intensive outpatient programs have multiplied in an attempt to improve care for high-need patients.1,2,3,4 These programs typically focus on patients with complex medical, social, and behavioral challenges who account for a disproportionate share of health care spending.5,6,7,8,9 Most provide comprehensive care coordination and a range of services such as home visits, health coaching for chronic conditions, after-hours access to providers, and social services for housing, transportation, and employment needs.1,3,10,11

Intensive outpatient programs have been implemented for diverse patient populations, including older adults,12,13,14 individuals with employment-based plans,15,16 and patients in safety net settings.3 Early evaluations suggest that these programs can improve patient outcomes, and several employer-based programs and for-profit corporations have reported cost savings as high as 15–50% in observational and retrospective internal evaluations.15,16,17 Randomized controlled trials of these programs, however, have generally reported more modest or negligible reductions in cost and utilization,18,19,20,21 with some notable exceptions of trials focusing exclusively on older adults.4

One explanation for the mixed evidence for intensive outpatient programs relates to patient engagement, the degree to which individuals actively participate and partner in their care. Patient engagement is increasingly recognized as integral to high-quality, patient-centered, and effective care.22,23,24 When patients engage in their clinical care, they are more likely to derive health benefits and to require fewer acute services for preventable conditions.25 Engagement is challenging, however, when patients face comorbid mental illness, social support or health literacy challenges, or financial stress.1,26 Many patients choose not to participate in intensive programs,20,27 and among individuals who enroll, many do not remain engaged in the programs for sustained periods.1

In order to maximize the value of intensive outpatient programs for high-need patients, we conducted a qualitative study to explore these programs’ approaches to engaging patients, their strategies to address specific engagement barriers, and cross-cutting lessons that can guide program design and service delivery.

METHODS

Qualitative study procedures were guided by the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (see Supplementary Appendix, online).28

Study Recruitment

Using convenience sampling, we recruited representatives from 18 intensive outpatient programs in diverse clinical settings in Northern California to participate in a qualitative study to learn about best practices for engaging patients in intensive outpatient programs; 12 programs chose to participate (67% response rate) (see Supplementary Appendix, online). For each program, we identified 1–2 key informants, including a front-line clinician and/or an individual involved in program management/leadership (N = 20). These participants were asked to complete a pre-interview online questionnaire describing program characteristics (95% response rate). We also asked program participants to estimate the proportion of patients who experience specific types of barriers to engagement (derived a priori from a literature review and discussion with content experts).

Interview Procedures

After obtaining informed consent, we conducted digitally recorded interviews (18 in person, 2 by phone) using a semi-structured interview guide (Supplementary Appendix, online). Interviews were conducted by a medical student (CO) who had no previous relationship with the interviewees and who was trained and supervised by a qualitative researcher (AN). During interviews, participants discussed engagement barriers facing their patient population and strategies that their programs use to address these engagement barriers. Interviews lasted between 25 and 55 min; only the interviewer and interviewee were present. Interviewees received $50 gift cards for their participation.

Study Framework

Qualitative content analysis was guided by the Engagement through CARInG Framework29 which categorizes patient engagement strategies into three domains: (1) Communication and Actions (i.e., strategies that support patients’ communication with providers, and their participation in recommended health care appointments and self-management activities), (2) Relationships built on trust (i.e., activities that are designed to build trust and confidence in the program team and health care system), and (3) Insight and Goal setting (i.e., counseling and other efforts to help patients gain insight and problem-solving capabilities).

Qualitative Data Analysis

Interviews were professionally transcribed and imported into ATLAS.ti to support data analysis and synthesis (ATLAS.ti7, Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany). Two authors (CO, CS) conducted directed content analysis of transcripts adapted from Hsieh et al. (2005),30 which involved deductive coding of engagement barriers and inductive coding of associated patient engagement strategies mapped to the domains of the CARInG Framework.29 Discrepancies were reviewed by a third researcher (DK) and resolved through group discussion.31 Next, all authors reviewed coded excerpts from each transcript and identified themes related to program features (i.e., program structure, resources, philosophy) that facilitate engagement. Two authors (CO, DZ) independently reviewed transcripts to identify illustrative quotes for each theme. In order to validate study findings, participants were invited to review preliminary results. In a follow-up group discussion by phone with nine participants, one novel theme emerged and was incorporated into study results and discussion. This study was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Study participants (N = 20) included physicians (N = 8), nurses/nurse practitioners (N = 4), a clinical psychologist (N = 1), a social worker (N = 1), a recreation therapist (N = 1), and medical assistant/peer coaches (N = 2); there were four participants who served solely as program administrators, and eight participants who held both clinical and program leadership roles. Programs were affiliated with diverse clinical settings, including academic medical centers (N = 2), county systems (N = 3), Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities (N = 2), community clinics (N = 3), a private healthcare system (N = 1), and a public payer (N = 1) (see Supplementary appendix, online).

Based on the pre-interview questionnaire, the most common barriers that impeded program engagement for a majority of patients were fragmentation across health systems, financial insecurity, mental illness, physical symptoms and limitations, and lack of social support (Table 1). Other common barriers to engagement included neighborhood and social environment, transportation challenges, housing instability, and alcohol/substance use. Engagement barriers that were frequently noted but affected fewer patients per program included health literacy difficulties, dementia/cognitive limitations, and distrust or negative feelings toward the healthcare system.

Intensive Outpatient Program Patient Engagement Strategies

In interviews, program leaders and clinicians described an array of approaches to address patient engagement. These are presented for each domain of the CARInG Framework,29 below and in Table 2.

Strategies that Support Patient Communication and Actions to Improve Health

Intensive outpatient programs use a wide range of strategies to facilitate patient communication and participation in recommended health-related activities. Many of the services address engagement barriers through concrete resources. For example, if a patient has financial constraints preventing appointment attendance, programs may arrange copay reductions or transportation vouchers, as a community health system nurse described, “We will ask them why did you miss your appointment?... ‘I don’t have a ride or I have heart failure and I can’t get on the bus and then walk’—so that’s when we provide the taxi vouchers.” For health literacy challenges that interfere with self-care, programs may label medications graphically, or visit the home to establish a safe medication system. When housing instability or safety is an issue, programs assist with housing applications or help a patient identify a safer living situation, such as a setting where an individual can recover from substance use disorder without exposure to others using drugs.

Programs also use a number of strategies to address fragmentation of care across different settings and providers: “Our team does a lot of coordinating between providers. That’s one of our major roles” (physician, county program). Strategies include co-attending appointments to coordinate care from different doctors, teaching patients how to navigate different systems, and facilitating information exchange by obtaining outside records on a patient’s behalf. These strategies serve as communication lines and access bridges, helping patients overcome the physical barriers that impede the use of available services and resources.

Strategies that Build Relationships and Trust

All program representatives described relationship-building approaches to engage patients who were distrustful of the medical system. Often, the programs begin by attempting to meet patients’ basic or most pressing needs, a process that may involve addressing housing instability, food insecurity, transportation challenges, employment, or social isolation before tackling health issues: “Food and transportation are kind of the life blood of being able to say, hey, we can provide this for you. And people come sometimes just because they want that and it’s okay… maybe this moment is going to be the moment that something happens in our relationship and maybe there will be a breakthrough” (non-clinical program manager, community health system). When patients are distrustful of the healthcare system or program, providers focus on communicating that they care about the patients as individuals and that they are “never giving up on them” (nurse practitioner, VA). Staff described visiting patients repeatedly in the hospital and community to build rapport. For example, one physician from a public payer program said, “[One] person wouldn’t engage but he kept reminiscing about fishing. And so our staff member brought fishing poles in and took the person fishing, and that’s what engaged him.” Programs also described building relationships with caregivers, and addressing their needs by identifying respite services and offloading activities that may be causing excess strain.

Strategies that Help Patients Gain Insight, Set Goals, and Problem Solve

A number of barriers were described as impeding patients’ insight and ability to set goals and problem-solve. Program representatives frequently described a process in which they initially problem-solved for patients, particularly when patients faced critical needs around housing, food insecurity, and finances. Over time, they would gradually introduce patients to skills and coping mechanisms so that they could begin to problem-solve for themselves. A nurse practitioner from a VA program explained that she would start by asking individuals about their personal barriers to better health, and then “help them work through that which will empower them to be more engaged, empower them to do self-care... It’s helping them to problem solve.” She provided the example of addressing health literacy challenges by co-attending appointments: “… I will ask a question that I know the answer to… so [patients] learn when I’m modeling for them how to handle providers, [by] saying, ‘I didn’t quite fully understand that; I really want to understand what you said, can you say that to me one more time in a way that I understand.’” Through these methods, programs help patients gain the skills needed to monitor and address their health issues, develop coping mechanisms, and seek the care they need.

Intensive Outpatient Program Features that Facilitate Patient Engagement

Qualitative data synthesis revealed several program features that influence patient engagement efforts, including: (1) team composition, hiring, and training activities; (2) resources and time; and (3) patient-centered philosophy (Table 3).

Team Composition, Hiring, and Training Activities

Program representatives frequently described their clinical team composition as important when attempting to engage patients. The multidisciplinary nature of most teams (see Supplementary Appendix, online) was cited as central to ensuring that individual patients’ needs—whether medical, social, or behavioral—were addressed. The diversity in schools of thought was described as a strength, because looking at a patient “through different lenses” increases the likelihood that “something will begin to stick” (nurse practitioner, VA program). Some discussed how including staff from diverse cultural, racial, and ethnic backgrounds facilitated communication. One non-clinical program manager from a community health system found it valuable to hire staff who had experienced challenges common among their patient population: “We have a lot of [staff] who have either been homeless themselves, or are in recovery from a mental health condition or substance use, and it’s amazing to watch [their] balance of compassion and clarity around what we can do for [our patients] and what their responsibility is in this.”

When discussing support for patient problem-solving, program representatives frequently described the importance of training staff in emotional intelligence, concrete skills such as trauma recognition, and motivational interviewing to help patients develop effective action plans. Program representatives also described the importance of hiring proactive staff who are willing to participate in activities that are not typical of their professional role. For example, a county program social worker described a scenario in which a patient did not respond to initial outreach efforts, but a case manager passed him daily at the subway station and chatted with him, “and after a couple of months he said, ‘You won’t give up on me so I’m not going to give up on myself,’ and [he] started services and was incredibly successful.”

Requisite Time and Resources for Patient Engagement Activities

Time and resources were described as essential for building relationships with patients. A clinical psychologist from a VA program said, “There is a culture on our team of giving people the time, space, and access that they need. And I think that really helps engage people who have trust issues.” The medical director and physician for a county program offered an anecdote that supported how time investments can build trust. When a patient needed an ID to reinstate his social security insurance, a community health worker from the program met the patient at the DMV: “They [stood] in line together for the morning, chatting about whatever, and then, inevitably, the crack use and the fact that he was shot at the other week comes out in the conversation.” These intimate details may not have emerged in the clinic environment during typically brief appointments.

A number of program representatives also commented on the time required to fully understand patients’ needs (including in-depth chart review, conversations with primary care providers, and comprehensive intakes with patients) and to coach patients around insight and goal-setting. As a nurse practitioner in a VA program observed, “This is not a quick fix.” Other time-intensive activities include co-attending appointments, following up after emergency department visits, and being available to address urgent needs. A physician co-director of a private healthcare system program described the importance of “just having [an] immediate response to people, be it night or day…” He said, “This weekend I talked to two people I’m sure would have gone to the emergency department if I hadn’t known them.”

Many program representatives raised the need for adequate and sometimes unconventional resources. Trust-building was often initiated through the use of discretionary funds to cover small gestures such as a sandwich, a birthday card, or bus tokens: “We offer bus tickets... And, you know, you can’t really control how somebody uses a bus ticket. Sometimes it’s just an investment in the relationship” (program manager, community health system). In addition, some programs supported patient self-care activities by distributing cell phones, or by offering technology such as read-aloud bariatric scales, language-concordant educational videos, and devices for telemental health, although the use and value of assistive technology varied across settings and patient populations.

Patient-Centered Philosophy

Finally, a third program feature that was described as critical to supporting patient engagement was a flexible approach centered around patient—not program—goals. This patient-centeredness was at the core of all programs represented in this study. As a non-clinical program administrator for a community health system program said, “I think trying to really listen to the patients and understand what they say their needs are—recognizing that the patient is the expert in their life and the patient is in charge of their health and healthcare whether or not the patient is engaged in that way—I think ultimately helps engage people because they feel respected.” Most programs focused on identifying individual patients’ priorities and addressing their most pressing needs first: “It takes a few visits [with the patient]… And a lot of the visits are based around what’s important for the patient, what is going on in their life at the moment because getting down to the root cause actually helps everything else” (care coordinator, private healthcare system program).

Providing patient-centered care often requires unconventional communication strategies and care settings: “I think being able to be super-mobile, have access to technology, have connections within the community, and have the option to do things a little bit differently has allowed us to be successful” (physician manager, public payer-sponsored program). These efforts were described as essential to creating a foundation for longer term engagement. A clinical psychologist at a VA program said his team tries to help with “whatever the patient needs.” He said, “We literally have gone and looked for legs, you know, prosthetic legs. And that’s not because we think it’s going to reduce utilization. It’s because we want to build trust.”

Managing Dysfunctional Forms of Engagement

A final theme that emerged during validation of study results with participants was that some patients exhibit dysfunctional engagement behaviors. For example, the medical director from a county program said that his team sometimes struggles with patients who selectively engage with social services, but are difficult to engage around their chronic illnesses. A clinical psychologist from a VA program reported that patients sometimes over-engage, demanding a level of resources that is not sustainable, so the team needs to be clear in stating, “We will teach you how to problem solve, we won’t do all of this for you.” Similarly, a program manager from a community program said that she has clients who like to engage with a lot of different agencies, which can result in agencies “tripping over each other” while patients over-utilize the systems without changing their behaviors. A strategy that her program has found helpful involves bringing representatives from the different agencies together to discuss how they will engage a specific client while reducing burden on the overall network of agencies. These comments highlight the challenge of engaging hard-to-reach patients in a way that is constructive and sustainable and that does not generate over-utilization.

DISCUSSION

Intensive outpatient programs use a broad range of strategies to foster trusting relationships with high-need patients, increase self-management and use of recommended health care, and help individuals develop insight, goal-setting, and problem-solving capabilities. This qualitative study suggests that patient engagement efforts may be enhanced by certain program features, such as a diverse multidisciplinary team, adequate staffing and resources to support relationship-building and intensive case management, and a patient-centered structure and philosophy.

Previous reports have described features of early intensive outpatient care models.3,4,32,33 For example, Hong et al. (2014) analyzed 18 complex care programs for high-need, high-cost patients and found that many programs focus on patient-provider and family-provider relationships, match team composition and interventions to patient needs, emphasize coordination of care, and offer specialized training to care providers.33 Bodenheimer et al. (2013) reviewed 14 high-utilizer programs for Medicaid patients and found additional common elements, including the use of health coaches to support self-management and adherence, and the provision of 24/7 access to the care team.3

Our qualitative study builds on these reviews by focusing on interventions and program design features that are specific to patient engagement, a commonly cited challenge for intensive outpatient programs. Findings provide evidence to support several program elements that may enhance engagement efforts. For example, program representatives described a program structure that enables staff to be flexible in meeting patients at their own pace, on their own terms, and—when appropriate—in their own homes or communities. Some programs focusing on patient populations in diverse, urban environments described how trusting relationships often developed through staff who have social, cultural, and/or racial/ethnic concordance with patients. Similarly, teams describe how incorporating diverse disciplines and perspectives increases the likelihood that a team member will form a connection with an initially skeptical patient. Importantly, while these program characteristics are unusual in conventional clinical settings, they were common among the intensive outpatient programs that we studied. This is likely because the programs are designed to explicitly address many of the medical, social, and behavioral challenges that generate patient engagement barriers in usual care.

Interestingly, the resource-intensive engagement activities described in this study may help explain the challenges that intensive outpatient programs often face in trying to reduce acute care utilization and contain costs for high-need patients. Not only is patient engagement time-intensive, but as patients become increasingly engaged, their interactions with the team may lead to identification of health issues that were previously undetected, resulting in more referrals and increased service use. Even if this care ultimately leads to better health and decreased risk for hospitalization, those longer-term effects of the program may not be exposed during a brief evaluation. Future research needs to examine the timeframe for productive engagement and incorporate engagement levels into evaluation analyses. In addition, it is important that evaluations extend beyond utilization and cost outcomes and consider patient experience and clinical outcomes,34 such as the degree to which the programs address medical and social determinants of health.35

A limitation of this study is its focus on program staff and leadership perspectives about effective engagement activities. Our findings are consistent, however, with qualitative studies of patients in intensive outpatient programs that suggest that patients value the relationships with staff and their assistance navigating medical and social systems,36 and also report improved health-related motivation, sense of control, and perceived health.36,37 This study is also exploratory in nature; as evaluations of intensive outpatient programs become increasingly available, synthesis of findings may shed light on the association between engagement strategies and clinical, utilization, and cost outcomes. Finally, the programs in this study are all located in Northern California, and the findings may not represent the experience of programs in other regions of the country.

In conclusion, this qualitative study highlights the range of clinical, interpersonal, and population-based approaches that intensive outpatient programs use to engage high-need patients. These programs almost universally offer patient-centered, individualized care that frequently deviates from standard practice. Findings suggest that programs aiming to increase engagement of complex, high-need patients should seek out creative and proactive staff, and ensure that they have adequate time, resources, and flexibility to address patients’ needs on patients’ terms.

References

Hasselman D. (Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc. ). Super-Utilizer Summit: Common Themes from Innovative Complex Care Management Programs. 2013.

Blumenthal D, Chernof B, Fulmer T, Lumpkin J, Selberg J. Caring for High-Need High-Cost Patients — An Urgent Priority. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2016(375):909–911.

Bodenheimer T. (Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc.). Strategies to Reduce Costs and Improve Care for High-Utilizing Medicaid Patients: Reflections on Pioneering Programs. 2013.

McCarthy D, Ryan J, Klein S. Models of care for high-need, high-cost patients: An evidence synthesis. Vol. 31: The Commonwealth Fund; 2015.

Mann C. Medicaid and CHIP: On the Road to Reform. Alliance for Health Reform/Kaiser Family Foundation. 2011. www.allhealth.org/briefingmaterials/KFFAlliance_FINAL-1971.ppt. Accessed 04/03/18.

Sommers A, Cohen M. Medicaid's High Cost Enrollees: How Much Do They Drive Program Spending? Kaiser Commission for Medicaid and the Uninsured. Washington, D.C. 2006.

Conwell LJ, Cohen JW. AHRQ Statistical Brief #73: Characteristics of persons with high medical expenditures in the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population, 2002. 2005. http://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/st73/stat73.pdf. Accessed 04/03/18.

Congressional Budget Office. High-cost Medicare beneficiaries. A CBO Paper. 2005. http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/63xx/doc6332/05-03-medispending.pdf. Accessed 04/03/18.

Zulman DM, Pal Chee C, Wagner TH, Yoon J, Cohen DM, Holmes TH, Ritchie C, Asch SM. Multimorbidity and healthcare utilisation among high-cost patients in the US Veterans Affairs Health Care System. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4).

Yee T, Lechner A, Carrier E. High-Intensity Primary Care: Lessons for Physician and Patient Engagement. National Institute for Health Care Reform. 2012;9.

California Healthcare Foundation, California Quality Collaborative. Complex Care Management Toolkit. 2012. http://www.calquality.org/storage/documents/cqc_complexcaremanagement_toolkit_final.pdf. Accessed 04/03/18.

Boult C, Reider L, Leff B, Frick KD, Boyd CM, Wolff JL, Frey K, Karm L, Wegener ST, Mroz T, Scharfstein DO. The effect of guided care teams on the use of health services: Results from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(5):460–6.

Dorr D, Wilcox AB, Brunker CP, Burdon RE, Donnelly SM. The effect of technology-supported, multidisease care management on the mortality and hospitalization of seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(12):2195–202.

Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, Tu W, Buttar AB, Stump TE, Ricketts GD. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(22):2623–33.

Blash L, Chapman S, Dower C. The Special Care Center - A joint venture to address chronic disease. Center for the Health Professions Research Brief. 2011.

Reuben DB. Physicians in supporting roles in chronic disease care: The CareMore model. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(1):158–60.

Milstein A, Kothari P. Are higher-value care models replicable? Health Affairs Blog. 2009. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2009/10/20/are-higher-value-care-models-replicable/. Accessed 04/03/18.

Shumway M, Boccellari A, O'Brien K, Okin RL. Cost-effectiveness of clinical case management for ED frequent users: Results of a randomized trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(2):155–64.

Sledge WH, Brown KE, Levine JM, Fiellin DA, Chawarski M, White WD, O'Connor PG. A randomized trial of primary intensive care to reduce hospital admissions in patients with high utilization of inpatient services. Disease Management. 2006;9(6):328–38.

Bell J, Mancuso D, Krupski T, Joesch JM, Atkins DC, Court B, West II, Roy-Byrne P. (Center for Healthcare Improvement for Addictions Mental Illness and Medically Vulnerable Populations, UW Medicine Harborview Medical Center). A randomized controlled trial of King County Care Partners’ Rethinking Care Intervention: Health and social outcomes up to two years post-randomization. 2012.

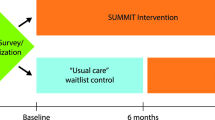

Zulman DM, Pal Chee C, Ezeji-Okoye SC, Shaw JG, Holmes TH, Kahn JS, Asch SM. Effect of an Intensive Outpatient Program to Augment Primary Care for High-Need Veterans Affairs Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):166–175.

Center for Advancing Health. A new definition of patient engagement: what is engagement and why is it important? 2010. http://www.cfah.org/pdfs/CFAH_Engagement_Behavior_Framework_current.pdf. Accessed 04/03/18.

Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, Sofaer S, Adams K, Bechtel C, Sweeney J. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Affairs. 2013;32(2):223–31.

Mittler JN, Martsolf GR, Telenko SJ, Scanlon DP. Making sense of "consumer engagement" initiatives to improve health and health care: a conceptual framework to guide policy and practice. Milbank Q. 2013;91(1):37–77.

Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Affairs. 2013;32(2):207–14.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance. 2008/10/01 ed: Medical Research Council; 2008.

Zulman DM, Ezeji-Okoye SC, Shaw JG, Hummel DL, Holloway KS, Smither SF, Breland JY, Chardos JF, Kirsh S, Kahn JS, Asch SM. Partnered Research in Healthcare Delivery Redesign for High-Need, High-Cost Patients: Development and Feasibility of an Intensive Management Patient-Aligned Care Team (ImPACT). J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(4):861–869.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57.

O'Brien CW, Breland JY, Slightam C, Nevedal A, Zulman DM. Engaging high-risk patients in intensive care coordination programs: The Engagement through CARInG Framework. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2018;8(3):351–56.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Saldana J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Third ed Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2015.

Brown RS, Peikes D, Peterson G, Schore J, Razafindrakoto CM. Six features of Medicare coordinated care demonstration programs that cut hospital admissions of high-risk patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(6):1156–66.

Hong CS, Siegel AL, Ferris TG. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients: what makes for a successful care management program? 2014.

McWilliams JM. Cost Containment and the Tale of Care Coordination. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375(23):2218–2220.

Ganguli I, Orav EJ, Weil E, Ferris TG, Vogeli C. What do high-risk patients value? Perspectives on a care management program. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(1):26–33.

Davis E, Tamayo A, Fernandez A. "Because somebody cared about me. That's how it changed things": homeless, chronically ill patients' perspectives on case management. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45980.

Mao AY, Willard-Grace R, Dubbin L, Aronson L, Fernandez A, Burke NJ, Finch J, Davis E. Perspectives of Low-Income Chronically Ill Patients on Complex Care Management. Fam Syst Health. 2017.

Funding

The study was supported by Veterans Affairs HSR&D Career Development Awards (CDA 12-173 and CDA 15-257) and a Stanford University School of Medicine MedScholars grant. Funding agencies had no role in the study’s design, conduct, or reporting.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors would like to thank the following program representatives for their study participation and contributions to this project: Robert Carr, Anna Chodos, Elizabeth Davis, Nate L. Ewigman, Brenda Goldstein, Courtney Gray, Kathryn Holloway, Debra Hummel, Debra Keller, Michael Kern, Ann Lindsay, David Moskowitz, Kathy O’Brien, Delila Pellot, Maria C. Raven, Laura Rombach Rau, Rebeca Servin, Jonathan Shaw, Ramona Soberanis, and Kathryn Stambaugh. We would also like to thank Steven Asch and Mary Goldstein for providing guidance during conceptualization of this project, and we would like to acknowledge content experts Clemens Hong, Ming Tai-Seale, and Brook Watts for reviewing and contributing to the list of patient engagement barriers that formed the basis of interviews.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board.

Prior presentations

This work was presented at the annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine, May 12, 2016 in Hollywood, FL, and at AcademyHealth on June 25, 2018 in Seattle, WA.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 25 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zulman, D.M., O’Brien, C.W., Slightam, C. et al. Engaging High-Need Patients in Intensive Outpatient Programs: A Qualitative Synthesis of Engagement Strategies. J GEN INTERN MED 33, 1937–1944 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4608-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4608-2