Abstract

This paper reviews The Ethics of Undercover Policing by Christopher Nathan.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Standard, overt policing has limited means of preventing crime and bringing wrongdoers to justice. In some instances, the use of undercover policing has better prospects. By concealing their identity and activity as agents of the state, undercover officers can more easily position themselves in strategic physical locations, get closer to criminals to obtain incriminating evidence and information, and so on. But it is fraught with potential moral problems. By its nature, undercover policing involves deception. It also often involves different degrees of manipulation. But deception and manipulation are deeply morally troubling in most other contexts. What, if anything, makes it permissible in the policing context? And when does legitimate undercover policing turn into wrongful entrapment?

Given the importance of these issues, one might expect there to be a vast literature on the morality of undercover policing. Yet, compared to the literature on many other kinds of prima facie morally problematic behaviour by the state (such as war and punishment), the literature on the ethics of policing, and undercover policing in particular, is sparse. Christopher Nathan’s The Ethics of Undercover Policing is therefore a very welcome addition.

The book is short – less than 50,000 words – and aims to be accessible to a wider academic audience. But throughout the 125 pages, Nathan does an impressive job of explaining many of the important moral issues relating to covert policing as well as developing novel views.

Chapter 1 provides an overview of different types of covert policing and responds to some fundamental objections to all kinds of undercover policing. Chapter 2 outlines the many different harms and prima facie wrongs associated with undercover policing and criticises three possible ways of justifying covert policing in light of these harms and wrongs (a dirty hands model, a consequentialist model, and a consent model). Instead, in Chapter 3, Nathan advances his own view of how to justify it – the Liability View – which borrows from the literature on the ethics of self-defence and just war theory. Chapter 4 continues to develop this view by tackling potential problems related to degrees of responsibility, lesser evil justification, epistemic limitations, and reparations. Chapter 5 provides a deeper analysis of manipulation and its wrongfulness. Lastly, Chapter 6 discusses various policy implications of Nathan’s views.

On the whole, it is a useful and interesting book. It is a comprehensive yet accessible introduction to some of the key ethical issues relating to covert policing. The Liability View is also a novel and important contribution to the debate. And since the development and defence of that view is one of the book’s main focuses, I will concentrate on it in this review. Despite my general sympathies for liability-based views, I have some reservations about Nathan’s view and its heavy reliance on analogies with the ethics of defensive harming. Below, I first explain the Liability View and then introduce two general worries about it – one about its extensional adequacy and one about its accuracy.

2 The Liability View

As Nathan points out, there are a variety of harms and prima facie wrongs involved in most instances of covert policing (pp. 25–30). Consider a hypothetical example:

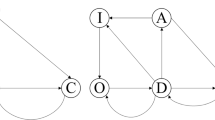

Undercover: Derek is the head of a ruthless criminal organisation. It has proven extremely difficult to bring him and the organisation down. The police therefore decide to use an undercover officer, Paul. Over several months, Paul builds up a reputation in the criminal underground and is finally accepted into Derek’s organisation. From there, he works his way higher up to become a trusted advisor to Derek. After a while, Paul has enough evidence and information to enable the police to bring Derek and his associates to court.

Before sending Paul out, the police know that Paul needs to cause harm and commit many prima facie wrongs on his way to the top. Two of the most salient prima facie wrongs are those of deception and manipulation. Obviously, he will have to deceive and manipulate Derek and others in the criminal organisation. But he may also have to deceive others. For instance, the partners and family members of Derek and the other gang members, other people he comes into contact with as part of his undercover job in the organisation, and so on. Perhaps, for instance, he gets to the top quicker by manipulating Derek’s mother, who is not involved in the organisation and thinks Derek’s business is legitimate. He may also cause considerable harm here. For instance, those deceived may forever have their ability to trust others damaged once it is revealed that Paul was undercover.Footnote 1

Still, if Derek’s organisation is dangerous enough, Paul’s actions seem justified. One of the central topics of Nathan’s book concerns how we should approach the question of justifiability. What normative model or framework should we use to judge the permissibility of an undercover operation in light of the harms and prima facie wrongs it involves?

Nathan proposes the Liability View, according to which the justifiability of a covert police mission is determined by roughly the same kinds of moral facts and principles which determine (according to many) whether a war, military operation, or act of individual self-defence is justified.

In the latter cases, a popular view goes as follows. Those responsible for unjust threats to innocent people are liable to be harmed for the sake of averting those threats (within limits set by necessity and proportionality constraints). That is to say that they have forfeited their rights against being harmed for such a cause. Thus, they lack a complaint against being harmed. In some cases, however, one has to cause harm to innocent bystanders in order to avert serious threats. On most views, this can also be justified, but the justification will be different in kind, for bystanders have done nothing to forfeit their rights against harm. Harming them for defensive purposes will therefore, at best, be justified as lesser evils. That is why it is more difficult to justify harming them and why they retain some complaint against the harm suffered.

Nathan recommends the same basic approach to undercover policing. Those involved in criminal activities make themselves liable to be manipulated and deceived for the sake of having those crimes prevented.Footnote 2 That is why Derek has no legitimate complaint against Paul’s deception and manipulation in Undercover. But it may also be permissible to deceive and manipulate non-criminals, such as his mother. This, however, will be justified as a lesser evil. Thus, the deception and manipulation we can impose on her will generally be much less grave than what we may impose on the liable Derek. She may also be entitled to some form of reparations later on. In this way, the model captures the intuitive sense that there are important differences in how one can justify targeting people in undercover operations.

On the surface level, a liability-based view is open-ended. The crucial question is what is supposed to ground the forfeiture of rights. In the defensive harming literature, as said, it is a person’s being responsible for a wrongful threat of harm. In the policing context, Nathan, in some places, says that it is a person’s culpably threatening “criminality” or their “threatened criminal activity” (p. 42) which grounds the liability. But what does this mean? It quickly becomes clear that Nathan takes the analogy with defensive harming very seriously. It appears that “threatened criminal activity” is understood as a shorthand for “threatened wrongful harm”. For as we read on, it is obvious that it is a person’s being responsible for a threat of wrongful harm which grounds their liability to deception and manipulation.

This is made explicit several times. For instance, in describing the liability of someone involved in the distribution of child sex abuse images, Nathan says: “[h]e is morally culpable for a threat in the sense that he is responsible for a possible harm; his actions render him liable to being used as a means to the end of preventing or mitigating that harm” (p. 42).Footnote 3 It is also made evident by the kinds of objections he considers, such as the worry that someone about to sell fake contraband to an undercover police officer will not be liable since he is not about to cause any harm (pp. 51–52).

A benefit of this approach is that it lowers the philosophical work required of Nathan. There has already been much work done in the defensive harming literature to explain why responsibility for a wrongful threat of harm ought to result in forfeiture of rights. If Nathan’s view were to focus on another ground of liability, we would expect Nathan to say much more about why forfeiture of rights follows. At the same time, however, I believe it is the fact that Nathan’s view is so heavily inspired by the ethics of self-defence which makes it problematic as a framework for determining the permissibility of undercover policing.

3 Crime and Harm

I worry that focusing on wrongful threats narrows the Liability View too much. There seem to be many cases in which a person’s criminal behaviour is not obviously linked to harmful threats. To see this, consider first one of Nathan’s cases, alluded to above (pp. 41–42):

Abuse: Danny is a member of a group which distributes images of child sex abuse online. To bring the organisation down, a police officer, Perry, starts deceiving and manipulating Danny online to trick him into revealing information about how they operate, his location, etc.

According to Nathan, it is Danny’s responsibility for a possible harm that makes him liable to be deceived and manipulated to prevent or mitigate said harm. Presumably, it is because Danny helps increase incentives to create more images, thus increasing the risk of harm to children, that he is responsible for “a possible harm”. But suppose that Danny is not involved in the group. Instead, he has hacked into their database and collects the images for himself. In that case, he is likely not increasing the risk of harm to children in the future. He may help decrease it in the sense that, had he not stolen them, he would have purchased the images from the group and thereby increased their financial incentives to continue harming children.

Still, Danny seems liable. We may deceive and manipulate him to stop his activitiesFootnote 4 and, if possible, we may deceive and manipulate him to try to get more information about the other group in order to bring them down.

Other cases illustrate the same issue. Consider Debbie. She is involved in the illegal importing and selling of marijuana. All her customers nevertheless willingly buy from her and consent to whatever harm they may suffer from using marijuana. In that case, it is unclear what threat of wrongful harm Debbie poses. However, even if one thinks that the use of marijuana should be legal, there may be legitimate reasons for a state to outlaw unregulated importing and selling of marijuana. The fact that Debbie is involved in that seems to me sufficient for her to lack a complaint against being targeted by undercover police.

Lastly, suppose that Dom is the creator of a tax evasion scheme. He will likely help others evade more than $1,000,000 in taxes next year. Surely, he is liable to be deceived and manipulated to be stopped. But what is the magnitude of the “possible harm” he is responsible for? Hiding $1,000,000 in taxes from a state will not likely make any person or group much worse off. More likely, I suspect, the deficit will be spread over several institutions, projects, and so on, and thus only cause many instances of negligible harm. So, Dom might not be liable to much deception after all if he is only responsible for several instances of negligible harm. Alternatively, we might aggregate these minor harms and deem Dom responsible for serious harm, but this option relies on a very contentious claim about aggregation.

Now, it is possible that we should aggregate and that, in the end, we can actually link Danny’s and Debbie’s actions to increased risks of harm.Footnote 5 My point, though, is that the intuition that they are liable does not hinge so absolutely on whether it is ultimately true that their individual actions increase the risk of serious harm. In my opinion, the simpler view of these cases is the following. States often have reasons to make certain behaviours illegal if the actions in question generally tend to be harmful or are harmful to society if enough people commit them. Those involved in such activities can make themselves liable to deception and manipulation, even when their particular illegal actions are not as clearly connected to risks of harm. At least, they can be liable to this if their arrest and punishment will also help deter others from engaging in the same behaviour and thereby decrease the risk of harm in a society.

This explanation, however, does not sit well with Nathan’s focus on defensive harming principles. Liability in that context is not standardly grounded in the same way. People do not make themselves liable to defensive harming just because their actions tend to be harmful. They are liable only if their actions will cause harm. In fact, most of the explanations of defensive liability rely on the claim that the liable agent will do harm unless harmed first.

So, to make room for liability in the cases above, I think Nathan should resist the temptation to rely on principles from the literature on the ethics of defensive harming. Instead, he may hold that it is “criminality” or “criminal activity” (understood as more than just threatening wrongful harm) which grounds liability to deception and manipulation. But that view, of course, requires more novel philosophical work.

4 Defence and Other Aims

There is also reason to suspect that Nathan focuses on the wrong grounds of liability even in cases where his account gets things extensionally correct. That is, cases in which the target of the covert policing is responsible for a wrongful threat of harm.

To see this, notice that our ideas about a successful undercover mission differ greatly from our ideas about successful preventive harming. Recall Undercover. Suppose that someone has left a computer logged into all of Derek’s organisation’s bank accounts. Paul sees it and realises he could bring down Derek’s operation here and now. Wiping the accounts will make it impossible for Derek’s organisation to continue.Footnote 6 However, Paul also knows that to get enough information and evidence to bring Derek and his associates to justice – not just bring the operation to the ground – he has to let the opportunity go and continue the manipulation for a while longer.

If Paul is just acting on Derek’s liability as a wrongful threatener, the necessity requirement demands using the least harm and deception necessary to avert the threat.Footnote 7 So, he should choose the first option. Clearly, however, if he is aiming for a truly successful undercover mission, he should choose the second option. As an undercover mission, just putting the organisation out of business seems like a partial failure or second-best outcome. In other words, undercover policing typically aims at more than just averting threats. It aims to achieve such prevention in a particular way, namely, the way that also brings the criminals to justice.

Nathan might, of course, embrace a mixed view. A person’s being responsible for a threat makes them liable to deception and manipulation, but other values and reasons – such as desert and general deterrence – may determine which means one should seek to prevent the threat and may even permit more deception and manipulation than strictly speaking necessary to prevent the threat.Footnote 8

Yet I want to suggest that these alternative reasons and values may do most, if not all, of the normative work. Sometimes, there is a worry that the Liability View will recommend too much harm. In the defensive context, people responsible for threats of serious bodily harm can make themselves liable to be seriously physically harmed, even killed, in other-defence. Suppose now that Derek’s organisation is occasionally responsible for causing others serious physical harm. Why is he not liable to be seriously physically harmed, or even killed, by the undercover officer? Nathan notes this worry, but his responses are unconvincing. He gestures towards possible contingent, instrumental, and pragmatic considerations to prohibit such harming by the police even if it could, in principle, be justified (pp. 57–58).

A more principled response is preferable. One such view holds that it is primarily a would-be criminal’s desert that justifies undercover policing. This may be desert grounded in past crimes as well as the wrong of trying to commit future crimes. On this view, Derek is liable to some degree of manipulation and deception as a means of being brought to justice and receiving the punishment he deserves. This is different from his liability qua wrongful threatener.

This view plausibly provides a more principled reason not to allow too much harm by undercover police officers. The reason is that the value of dishing out a deserved punishment is, generally, less morally important than preventing wrongful harm. Imagine you have to choose between preventing a murder and ensuring that a murderer gets the punishment they deserve. The former seems several times more morally important. Thus, it is plausible to think that the maximally proportionate harm one can impose to achieve the former is significantly higher than what one can impose to ensure the latter.

Though more must be said, of course, the two points made here suggest that a more desert-focused approach to the ethics of undercover policing is better able to account for the intuitions that (i) undercover policing aims at criminal justice, not just threat prevention and (ii) the constraints on the permissible means of undercover policing are stricter than the constraints on the permissible means of defensive harming.

5 Conclusion

These criticisms are not meant to decisively rule out the Liability View and should be taken as an invitation for further development of the view. And despite the objections, Nathan’s book is to be recommended. It is a helpful and accessible guide to many pressing questions surrounding the important topic of undercover policing.

Notes

Naturally, Paul might also have to commit crimes in order to build trust. Nathan discusses this issue more in Chapter 6.

Nathan (pp. 53–56) allows for the view that covert policing sometimes only aims at bringing someone to justice for an already committed crime. To do so, he borrows from Tadros’ (2011) views on punishment, claiming that criminals might owe their victims and society a debt which requires them to be punished.

The language of and focus on “threats” continues throughout the chapter. See, for instance, p. 51, p. 62, p. 63.

It may not be the best use of scarce police resources if he is not increasing the risk of harm, but it seems to me that he nevertheless lacks a complaint against the deception.

Nathan (2017, pp. 380 − 81) talks more about these latter two kinds of cases and seems to opt for this strategy.

Let us also add that Derek, already quite old, will not try to rebuild a similar organisation.

Nathan (pp. 49–51) is sceptical of the necessity requirement, but his scepticism is grounded in issues concerning uncertainty, so they are not applicable in this scenario where we can stipulate full knowledge.

In fact, Nathan (p. 55) seems open to this kind of view.

References

Nathan, C. (2017). “Liability to Deception and Manipulation: The Ethics of Undercover Policing,” Journal of Applied Philosophy 34(3): 370–388.

Tadros, V. (2011). The Ends of Harm: The Moral Foundations of Criminal Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

Not applicable.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Haeg, J. Review of Christopher Nathan, The Ethics of Undercover Policing (Routledge, 2022). Criminal Law, Philosophy 18, 315–323 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11572-023-09715-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11572-023-09715-2