Abstract

We present a model with multiple donors-principals that provide funds to a unique recipient-agent. Each donor decides how to allocate his aid funds between a pooled and an unilateral project. Both the principals and the agent value the output produced with the pooled funds and the unilateral projects. However donors have a bias in favor of their own unilateral project, which leads them to over-invest in these projects. We propose a tax scheme on the unilateral projects, which acts as a protection measure against biased allocation by the principals. The optimal tax imposed on unilateral projects varies depending on the total amount of aid provided by the donor and on the productivity of his unilateral project. Such a mechanism fits into the current discussion on bilateral negotiations on aid funds tax exemptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For instance US foreign assistance programs are fragmented across more than 50 bureaucracies and USAID is overseeing only 45% of total US foreign aid (Brainard 2007). Similarly in Germany the ministry for international cooperation coordinates less than 40% of all German development aid. See http://ipsnews.net/news.asp?idnews=46043

For example, the Tanzanian government has to prepare over 2000 reports to donors and 1000 delegations every year (Easterly and Birdsall 2008). The management of donor visits became such a big problem that the country had to declare a ‘mission holiday’ – a four month period to take a break from visiting delegations (Birdsall 2005). Each of the donors represents different accountability and procurement rules, and the need to make the project the donors want to fund match with the existing recipient country’s portfolio.

We focus on the donor’s allocation of funds between unilateral projects and projects coordinated with other donors at the recipient country level. We do not include in our model the donor’s choice between multilateral and bilateral aid. The literature on multilateral versus bilateral aid is extensive (see Gulrajani (2016) for a recent survey, and Findley et al. (2017) for discussion on effectiveness of each type of aid) and the discussion on the proliferation of multilateral institutions is active (see Kellerman 2018), as is the literature on the political influence in these institutions.

For instance among the 3700 aid relationships tracked down in the OECD Development Co-operation Report (OECD 2008a), 600 are micro-aid schemes of under USD 250 000 per year each, and amounting to only 0.1% of country programmable aid. More generally in 2005-06, 38 partner developing countries had more than 25 official donors, most of them small. In 24 of these developing countries, 15 or more donors provided less than 10% of that country’s total aid (OECD 2008b).

See for example Balogun (2005) for the distinction between harmonization of procedures, alignment of objectives and ownership.

There is a vast literature on aid contracting, including among others Azam and Laffont (2003), Svensson (2003), and Morrissey et al. (2012), that works on conditionality. This literature also looks at the issue of aid effectiveness from the donors perspective: The problem is the recipient behavior and aid conditionality is a tool to control the use of aid.

See OECD (2008a) for more detail on the Accra Agenda for Action or http://www.oecd.org/dac/effectiveness/parisdeclarationandaccraagendaforaction.htm.

Appendix available at the Review of International Organizations’ webpage.

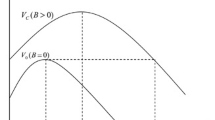

We focus on a Cobb-Douglas production function to keep the exposition simple as it yields closed form solutions. However our results are robust to production functions that are increasing and concave in the aid investments and exhibit complementarity in the different aid projects. In the limit the aid budgets are strictly complementary (i.e., Leontief production function). With such extreme production function our results are exacerbated as aid is wasted when the different budgets are not in the right proportion of each other. By contrast if all the aid projects are perfect substitutes (i.e., the development production function is proportional to the sum of all the aid money), it does not matter how much each donor puts in his “project” as they are all substitutable. This is a case where any allocation is efficient, conditional on the fact that the recipient can handle it.

In kind aid of left overs is generally a poor match for the recipient needs. To illustrate what a SWEDON is, see for instance “Bad Charity? (All I Got Was This Lousy T-Shirt!)” By Nick Wadhams in Time May 12, 2010 available at http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1987628,00.html.

As Bobba and Powell (2006) show, donors face a trade-off between coordination costs and dilution of individual objectives when choosing between bilateral and multilateral contributions.

We abstract here of interactions among the different projects on effort costs. For example, Knack and Rahman (2007a) study how recipient’s bureaucratic quality is affected by donor’s preferences and number of projects.

It is worth noting that even if they are fully benevolent (i.e. if ζk = 0 and Γ = 0), the donors and the recipient do not have the same objective function. The donors do not internalize the administrative cost imposed by aid management. In practice administrative capacity is a public good, which yields problem of free-ridding: everybody would like the other to finance it. It is also a black box for the donors that could hide corruption. At least development outcome is a “clean” objective and is easier to sell politically to their constituencies (i.e., taxpayers in advanced economies). It is easier to communicate around new schools or new dams than around elusive “better state capacity.”

To get \(u_{2}^{\ast }= 0\) requires c2 to be so that \({\partial U_{2}(u_{1}, u_{2})\over \partial u_{2}} = -(1+c_{2})\alpha _{p} u_{1}^{\alpha _{1}}p^{\alpha _{p}-1} +\zeta H^{\prime }(u_{2}) <0\).

We set \(x=\sqrt {\frac {p}{u_{1}}}\) and solve the second order equation (32): x2 + 2ζ1x − (1 + c1) = 0. Taking the square of the only positive root, yields \(\frac {p}{u_{1} }=\left (\sqrt {1+c_{1}+{\zeta _{1}^{2}}}-\zeta _{1}\right )^{2} \). Substituting p = B − (1 + c1)u1 in this equation and solving it yields \(u_{1}^{\ast \ast }\) in Eq. 33.

References

Acharya, A., Fuzzo de Lima, A., Moore, M. (2004). Aid proliferation: how responsible are the donors? IDS Working paper.

Asongu, S.A. (2012). On the effect of foreign aid on corruption. Economics Bulletin, 32(3), 2174–2180.

Azam, J.-P., & Laffont, J.-J. (2003). Contracting for aid. Journal of Development Economics, 70(1), 25–58.

Balogun, P. (2005). Evaluating progress towards harmonization. DFID Working paper.

Bernheim, B.D., & Whinston, M.D. (1986). Common agency. Econometrica, 54(4), 923–942.

Bigsten, A. (2006). Donor coordination and the uses of aid. Working paper.

Birdsall, N. (2005). Seven deadly sins: reflections on donor failings. Working paper GDN.

Bobba, M., & Powell, J. (2006). Multilateral intermediation of foreign aid: what is the trade-off for donor countries? Inter-American Development Bank working paper.

Brainard, L. (2007). Organizing us foreign assistance to meet twenty first century challenges. In Brainard, L. (Ed.) Security by other means: foreign assistance, global poverty, and American leadership. Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Brazys, S., Elkink, J.A., Kelly, G. (2017). Bad neighbors?: how co-located chinese and world bank development projects impact local corruption in tanzania. The Review of International Organizations, 12(2), 227–253.

Djankov, S., Montalvo, J.G., Reynal-Querol, M. (2009). Aid with multiple personalities. Journal of Comparative Economics, 37(2), 217–229.

Doucouliagos, H., & Paldam, M. (2009). The aid effectiveness literature: the sad results of 40 years of research. Journal of Economic Surveys, 23(3), 433–461.

Dreher, A., Klasen, S., Vreeland, J.R., Werker, E. (2013). The costs of favoritism: is politically driven aid less effective? Economic Development and Cultural Change, 62(1), 157–191.

Dreher, A., Minasyan, A., Nunnenkamp, P. (2015). Government ideology in donor and recipient countries: does political proximity matter for the effectiveness of aid? European Economic Review, 79(11), 80–92.

Dreher, A., Nunnenkamp, P., Thiele, R. (2011). Are new donors different? comparing the allocation of bilateral aid between nondac and dac donor countries. World Development, 39(11), 1950–1968.

Easterly, W., & Birdsall, N. (2008). Reinventing foreign aid. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Easterly, W., & Pfutze, T. (2008). Where does the money go? best and worst practices in foreign aid. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(2), 29–52.

Easterly, W., & Williamson, C.R. (2011). Rhetoric versus reality: the best and worst of aid agency practices. World Development, 39(11), 1930–1949.

Findley, M.G., Milner, H.V., Nielson, D.L. (2017). The choice among aid donors: the effects of multilateral vs. bilateral aid on recipient behavioral support. The Review of International Organizations, 12(2), 307–334.

Gehring, K., Michaelowa, K., Dreher, A., Spoerri, F. (2017). Aid fragmentation and effectiveness: what do we really know? World Development, 99, 320–334.

Gulrajani, N. (2016). Bilateral versus multilateral aid channels: strategic choices for donors. ODI Report.

Halonen-Akatwijuka, M. (2007). Coordination failure in foreign aid. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 7(1), 1–40.

Isaksson, A.-S., & Kotsadam, A. (2018). Chinese aid and local corruption. Journal of Public Economics, 159, 146–159.

Jones, S., & Tarp, F. (2016). Does foreign aid harm political institutions? Journal of Development Economics, 118, 266–281.

Kellerman, M. (2018). The proliferation of multilateral development banks. The Review of International Organizations.

Kilby, C., & Dreher, A. (2010). The impact of aid on growth revisited: do donor motives matter? Economics Letters, 107(3), 338–340.

Knack, S. (2013). Aid and donor trust in recipient country systems. Journal of Development Economics, 101, 316–329.

Knack, S., & Rahman, A. (2007a). Donor fragmentation and bureaucratic quality in aid recipients. Journal of Development Economics, 83(1), 176–197.

Knack, S., & Rahman, A. (2007b). Donor fragmentation and bureaucratic quality in aid recipients. Journal of Development Economics, 83(1), 176–197.

Knack, S., & Rahman, A. (2008). Donor fragmentation. In Reinventing Foreign Aid (Cambridge, Editor W. Easterly).

Knack, S., & Smets, L. (2013). Aid tying and donor fragmentation. World Development, 44, 63–76.

Minasyan, A., Nunnenkamp, P., Richert, K. (2017). Does aid effectiveness depend on the quality of donors? World Development, 100, 16–30.

Morrissey, O., Clist, P., Isopi, A. (2012). Selectivity on aid modality: determinants of budget support from multilateral donors. Review of International Organizations.

OECD. (2008a). Report on the division of labor: addressing global fragmentation and concentration. OECD_Development Co-operation Directorate Report.

OECD. (2008b). Survey on monitoring the paris declaration: making aid effective by 2010. OECD_ Development Assistance Commitee.

Okada, K., & Samreth, S. (2012). The effect of foreign aid on corruption: a quantile regression approach. Economics Letters, 115(2), 240–243.

Rajan, R.G., & Subramanian, A. (2008). Aid and growth: what does the cross-country evidence really show? Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(4), 643–665.

Roodman, D. (2006a). Aid project proliferation and absortive capacity. Working paper, Center for Global Development.

Roodman, D. (2006b). Competitive proliferation of aid projects: a model. Working paper, Center for Global Development.

Steel, I., Dom, R., Long, C., Monkam, N., Carter, P. (2018). The taxation of foreign aid. ODI Briefing Note.

Svensson, J. (2003). Why conditional aid does not work and what can be done about it? Journal of Development Economics, 70(2), 381–402.

Tingley, D. (2010). Donors and domestic politics: political influences on foreign aid effort. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 50(1), 40–49.

Walz, J., & Ramachandran, V. (2011). Brave new world a literature review of emerging donors and the changing nature of foreign assistance. Working paper, Center for Global Development.

Williamson, C., Agha, A., Bjornstad, L., Twijukye, G., Mahwago, Y., Kabelwa, G. (2008). Building blocks or stumbling blocks? the effectiveness of new approaches to aid delivery at the sector level. ODI Working paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the nancial support of the French Development Agency (AFD). We thank for their comments seminar audiences at the University of Padova and at the French Development Agency (AFD). We are also extremely grateful for the insightful comments and suggestions of Nicolas Vincent, Paola Valbonesi and GaŁelle Balineau. Finally we want to thank four anonymous referees for their comments and suggestions that helped us to greatly improve the paper. All remaining errors are ours.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Auriol, E., Miquel-Florensa, J. Taxing fragmented aid to improve aid efficiency. Rev Int Organ 14, 453–477 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-018-9329-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-018-9329-0