Abstract

This paper explains variations in education spending among non-democracies, focusing on policy interdependence by trade competition. Facing pressures from spending changes in competitor countries, rulers calculate the costs and benefits associated with increased education spending: education increases labor productivity; it also increases civil engagement and chances of democratization. Therefore, we expect that rulers in countries whose revenues depend less on a productive labor force and those with shorter time horizons are less likely to invest because of lower expected benefits; rulers with single-party regimes, authoritarian legislatures, and especially partisan authoritarian legislatures are more likely to invest because such institutions enable them to better survive the threats associated with increased human capital. We find empirical support for policy interdependence and the conditional effects of government revenue source, time horizon, and partisan legislatures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

However, recent work has started to question the importance of the democracy vs. non-democracy dimension in understanding distributive policymaking in general. For instance, Mulligan et al. (2004) find no difference in public policies between economically similar democracies and non-democracies. Ross (2006) shows that in policy outcomes such as infant and child mortality rates, democracies are not better than non-democracies despite more money spent on education and health.

Note that the two aforementioned examples – Malaysia and Indonesia – were both stable authoritarian regimes, the former ruled by a dominant party and the latter a military dictator.

However, evidence on the connection between democracy and tertiary education is often mixed.

The exceptions could be countries that monopolize a certain sector of the global market such as some large oil-exporting countries.

Education spending, given its direct effect on human capital, is different from other components of social spending. Take primary education as an example, on the one hand, there is unlikely to be pressure for more spending on primary education to compensate citizens facing increased insecurity due to globalization (compensation hypothesis). On the other hand, the efficiency hypothesis might not work, either, because governments are likely to be pressured by business leaders to improve human capital via education spending. The effects of globalization on education spending might also depend on government development strategies and the comparative advantage of the economy: those specializing in labor intensive production might try to cut social spending while those requiring increased human capital or upgrading might need further investment in education (Hecock 2006).

Our empirical analysis finds that trade openness has no effect on education spending in authoritarian states; nor does it mediate the effect of the trade competition variable defined as the weighted average level of education spending in trade competitor countries.

Recent studies show that diffusion mechanisms are present in a variety of areas such as social welfare policies (Brooks 2005; Gilardi 2007; Cao 2010, 2012b), economic liberalization (Way 2005; Simmons 2004; Elkins et al. 2006), financial regulations (Brooks and Marcus 2012), and environmental policies (Busch et al. 2005; Ward and Cao 2012; Cao and Prakash 2010, 2012a).

We focus on export competition in this study. On how import competition creates policy diffusion between a country and its import-competitor countries, see López-Cariboni and Cao (2015).

As De Mesquita and Smith (2010) summarized: “educated people with access to transport and knowledge of the market are more productive than ignorant and isolated people.”

“Economic backwardness” is more likely when the ruling elite is somewhat entrenched but still fears replacement (Acemoglu 2006, ).

The causal chain is a long one: education spending improves productivity, which in turn increases competitiveness in global markets and ultimately increase government revenue. We acknowledge the presence of intermediate variables along the causal chain, but the fact that we find significant results shows that our theory works despite potential intermediate conditions.

For instance, in a sub-national context, Hong (Forthcoming) shows that Chinese local governments with a large natural resource sector have few incentives to invest in labor productivity enhancing social services because abundant resources decrease the need to attract outside investments which often favor higher labor quality.

We make a simplifying distinction between sectors of the economy that are resources-based and those that depend more on a productive population. However, oil, natural gas, and mineral extraction industries are different from agriculture and other primary activities based on relatively large land-endowment. We focus on the former type of natural resources because oil and minerals usually are geographically concentrated and easier for the state to control. They are often important components of non-tax government revenue.

However, Jerry J. Rawlings of Ghana and Joaquim A. Chissano of Mozambique actually won two presidential elections after democratization of the country.

See http://www.personal.psu.edu/jgw12/blogs/josephwright/WrightEscribaBJPSAppendix.pdf, accessed on May 30, 2013.

The other type of threats for the ruler are those that emerge from within the ruling elite. They are often dealt by establishing narrow institutions such as consultative councils, juntas, and political bureaus (Gandhi and Przeworski 2007).

How authoritarian legislature works still is an ongoing research topic, for an online discussion from experts, see http://themonkeycage.org/2012/12/what-do-legislatures-in-authoritarian-regimes-do/.

Data on education spending are from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, the Edstats dataset from the World Bank. Results for spending as a percentage of total government spending are similar and available upon request.

While excluding capital expenditures, this variable provides information for a large number of countries over time. An alternative measure is current and capital public education expenditure. This data is however very sparse and provides a much smaller number of observations with shorter country time series: for 1970-2009, almost half of the countries have less than 10 observations and almost 30% of countries have fewer than 5 observations. As robustness checks, we did run the same analysis using current and capital public education expenditure as the dependent variable. We find strong evidence for policy interdependence.

For a more detailed explanation of the spatial lag variable, see Section A of the Online Appendix.

Note that the ECM is arithmetically equivalent to a general ADL specification (De Boef and Luke 2008; Keele et al. 2016), and that the spatio-temporal autoregressive model (STAR) is in fact an ADL model with spatial lags. Model selection for TSCS depends on both theoretical and empirical considerations. Potential concerns are the order of integration and whether there exists equation balance in the model (Grant and Lebo 2016). We performed different panel unit root tests for both the education spending data and the spatial lag of education spending. The tests are panel unit root test either based on a pooled statistic (Levin et al. 2002), or a group-mean test averaging augmented Dickey-Fuller regressions for each time series (Im et al. 2003). The evidence suggests we are dealing with stationary data on both sides of the equation. We also performed these tests with unbounded time series data (Lebo and Grant 2016; Grant and Lebo 2016), by taking education spending measured in constant US dollars. Again, unit root tests confirm that our data is most likely to be I(0). This strengthens our confidence in reporting reliable hypothesis testing and long-run multipliers for the substantive interpretation size effects (Grant and Lebo 2016; Keele et al. 2016).

In some of our specifications where we still observe serially correlated disturbances due to the the persistence of education spending data and different sample sizes, we include lagged differences of the dependent variable as a means of purging the remaining autocorrelation.

Results remain unchanged after controlling for aggregate signs of external competitiveness like the external trade balance and consumption prices.

Including the Polity score in specifications with other institutional variables such as legislatures or authoritarian regime types might be redundant, because for some countries, it might pick up certain level of the same information contained in other institutions variables. Excluding the Polity score, however, does not change the main results: regression tables are available upon request from authors.

The per capita income data comes from expanded times series by Gleditsch (2002), updated in 2013. The output gap is estimated as the difference between real GDP per capita and the underlying growth trends, as a percentage of the trend. A Hodrick-Prescott filter (H-P) is used to estimate the underlying growth trend. The H-P filter implements long-run moving average to de-trend the output series. See: (Kaufman and Segura-Ubiergo 2001, 584).

Data are from the World Bank, World Development Indicators (The World Bank 2012).

Using total government spending does not changes the results, but it significantly shrinks the sample size. Data are from the IMF-GFS and the World Development Indicators (The World Bank 2012).

We follow the standard Bewley transformation of error correction model to calculate the long-run multipliers and their corresponding standard errors. See De Boef and Luke (2008).

Adding changes and their interactions with domestic conditional variables makes no difference to the conclusions we arrive from the empirical analysis.

Another way that trade openness could affect education spending is through its mediating effect with trade competitors’ education expenditures. Not all countries are equally open to trade. The same level of spending increase in competitor countries might have a larger impact on a more open economy. We need to test an interactive effect between trade openness and trade competitors’ education expenditure changes. We have tried various openness variables (imports, exports, and total trade) and trade liberalization index (e.g., the KOF index Dreher 2006; Gygli et al. 2018); they do not mediate the effect of interdependence. However, we do find that our results regarding education spending races among trade competitor countries are more important for the period of 1990-2009 (high global economic integration) than for the period of 1970s and 1980s (low economic integration) for developing nations. See Section I of the Online Appendix for more details.

Oil and natural resource rents data are from the World Bank, World Development Indicators. Since both variables are highly skewed, we log transform the data before estimating the models. Taking into account of production costs is very important given the significant cross-country variation in the cost of producing a barrel of oil: in the United Kingdom, it costs $52.50 to produce a barrel of oil; in Brazil, it costs nearly $49; on the other hand, Saudia Arabia and Kuwait can pump a barrel of oil for less than $10 – see http://money.cnn.com/2015/11/24/news/oil-prices-production-costs/index.html, accessed on November 30, 2017. Ross (2012) offers an alternative measure of oil and gas wealth by dividing the total value of oil and gas production by a country’s population. We think this is a very important measure for a country’s overall oil and gas wealth. But it does not take into account the aforementioned cross-country variation in the cost of production which significantly affects the amount of rents that can be captured by an autocratic ruler. Nevertheless, we conducted robustness checks using this oil income per capita variable. The detailed results are in Section D of the online appendix: we observe a very similar finding – rulers with no natural resources engage in education races; as oil and gas income per capita increases, the effect of interdependence becomes insignificant.

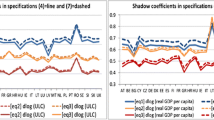

The results here need to be interpreted with caution regarding the substantive effect, especially for areas around extreme values such as those close to the maximum value of the oil variable, because on the maximum side, there are not many observations in the data. As a function of this, the confidence intervals of coefficient estimates when the resource variables approach their maximum values are often large and overlap with the confidence intervals when the values of the resource variables are close to 0 (Fig. 3).

See also Cheibub (1998) who uses predicted hazard rates for leadership failure.

Also, shortened time-horizons may affect education spending negatively if education spending among trade competitor countries is high.

Data are from the World Bank, World Development Indicators.

Section H of the online appendix has more detailed discussion on model estimates.

We thank one reviewer for raising this interesting alternative causal mechanism.

It is possible that these two proxies might not be able to pick up enough variation in the political strength of of teachers’ unions, especially in cross-country context.

We have also replicated estimates from the main paper clustering standard errors to correct for potential time-wise heteroscedasticity and cross-sectional heteroscedasticity and correlation. As shown by Section L and Table 14 of the online appendix, there is no significant difference compared to spatial OLS models in the main paper.

This type of quality improvements can happen in relatively short periods, which allow for increased market shares in export destinations by selling better quality products with only moderate changes in price.

Even at the extensive margin, geographic diversification is more important than the upgrading process that leads to product diversification.

We have argued that partisan legislatures matter because they better enable the two important instruments for authoritarian regime survival: policy concessions and cooptation. Future analysis should look at via which instrument(s) partisan legislature affects regime survival.

For instance, Boix (1997) finds that left-wing governments spend heavily in physical and human capital formation to raise the productivity of factors and the competitiveness of the economy.

Interestingly, we find no evidence for an education spending race in developed country democracies and a negative and significant long-term effect of trade competition in developing country democracies. Details are reported in the Online Appendix, Section C. Why developing country democracies would spend less on education when their trade competitor countries spend more? Our speculation is that when trade competitors invest in education which causes actual or perceived loss of competitiveness for a developing democracy, the country reacts by increasing compensation to trade losers using “short-term-solution” policy instruments (e.g., subsidies) at the expense of the education spending.

Of course, mass mobilization is not a perfect measure of collective action. But in autocracies, mass mobilization is probably among the few ways for the public to express political demands.

This shift in focus to educational inequality is also raised by a recent review essay by Gift and Wibbels (2014).

References

Acemoglu, D.J.A. (2006). Robinson Economic backwardness in political perspective. American Political Science Review, 100(1), 115–131.

Aldomd, G., & Verba, S. (1963). The civic culture: Political attitudes and democracy in five nations princeton. NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ames, B. (1987). Political Survival: Politicians and Public Policy in Latin America Vol. 12. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Amurgo-Pacheco, A., & Denisse Pierola, M. (2008). Patterns Of Export Diversification In Developing Countries: Intensive And Extensive Margins. Policy Research Working Papers The World Bank https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/1813-9450-4473.

Ansell, B.W. (2008). Traders, teachers, and tyrants: democracy, globalization, and public investment in education. International Organization, 62(02), 289–322.

Ansell, B.W. (2010). From the ballot to the blackboard: the redistributive political economy of education. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Avelino, G., Hunter, D.S., Brown, W. (2005). The effects of capital mobility, trade openness, and democracy on social spending in Latin America, 1980-1999. American Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 625–641.

Balassa, B. (1981). The newly industrializing countries in the world economy. New York: Pergamon Press.

Baum, M.A.D.A. (2003). Lake The political economy of growth: Democracy and human capital. American Journal of Political Science, 47(2), 333–347.

Blanco, L., & Grier, R. (2012). Natural resource dependence and the accumulation of physical and human capital in Latin America. Resources Policy, 37(3), 281–295.

Boix, C. (1997). Political parties and the supply side of the economy: The provision of physical and human capital in advanced economies, 1960-90. American Journal of Political Science, 41(3), 814–845.

Boix, C., & Stokes, S.C. (2003). Endogenous Democratization. World Politics, 55(4), 517–549.

Bourguignon, F., & Verdier, T. (2000). Oligarchy, Democracy, Inequality and Growth. Journal of Development Economics, 62(2), 285–313.

Brady, H.E., Verba, S., Schlozman, K.L. (1995). Beyond ses: a resource model of political participation. The American Political Science Review, 89(2), 271–294.

Brooks, S.M. (2005). Interdependent and domestic foundations of policy change: The diffusion of pension privatization around the world. International Studies Quarterly, 49(2), 273–294.

Brooks, S.M. (2007). When does diffusion matter? explaining the spread of structural pension reforms across nations. The Journal of Politics, 69, 701–715.

Brooks, S.M., & Marcus, J. (2012). Kurtz paths to financial policy diffusion: Statist legacies in latin america’s globalization. International Organization, 66(1), 95–128.

Brown, D.S. (1999). Wendy hunter democracy and social spending in latin america, 1980-92. American Political Science Review, 93(4), 779–790.

Brown, D.S. (2004). Wendy hunter democracy and human capital formation. Comparative Political Studies, 37(7), 842–864.

Busch, P.-O., Tews, H., Kerstin, J. (2005). The global diffusion of regulatory instruments: The making of a new international environmental regime. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 598, 146–167.

Cameron, D.R. (1978). The expansion of the public economy: a comparative analysis. American Political Science Review, 72(4), 1243–1261.

Campante, F.R., & Chor, D. (2012). Schooling, political participation, and the economy. Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(4), 841–859.

Campbell, D.E. (2006). Why we vote: How schools and communities shape our civic life. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Cao, X., & Prakash, A. (2010). Trade competition and domestic pollution: a panel study, 1980–2003. International Organization, 64(03), 481–503.

Cao, X., & Prakash, A. (2012a). Trade competition and environmental regulations: Domestic political constraints and issue visibility. The Journal of Politics, 74(01), 66–82.

Cao, X. (2012b). Global networks and domestic policy convergence: a network explanation of policy changes. World Politics, 64(3), 375–425.

Castelló, A., & Doménech, R. (2002). Human capital inequality and economic growth: Some new evidence. The Economic Journal, 112(478), C187–C200.

Castelló-Climent, A. (2008). On the distribution of education and democracy. Journal of Development Economics, 87(2), 179–190.

Cheibub, J. (1998). Antonio political regimes and the extractive capacity of governments: Taxation in democracies and dictatorships. World Politics, 50, 349–376.

Cheibub, J., Antonio, V., Gandhi, J., Raymond, J. (2010). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice, 143(1-2), 67–101.

Dahlum, S., & Wig, T. (Forthcoming). Educating Demonstrators: Education and Mass Protest in Africa. Journal of Conflict Resolution.

De Boef, S., & Luke, S. (2008). Taking time seriously. American Journal of Political Science, 52(1), 184–200.

De Mesquita, B.B., & Smith, A. (2010). Leader survival, revolutions, and the nature of government finance. American Journal of Political Science, 54(4), 936–950.

Dee, T.S. (2004). Are there civic returns to education? Journal of Public Economics, 88(9-10), 1697–1720.

Doner, R.F., Ritchie, B.K., Slater, D. (2005). Systemic Vulnerability and the Origins of Developmental States: Northeast and Southeast Asia in Comparative Perspective. Vol. 59 .

Dreher, A. (2006). Does Globalization Affect Growth? Evidence from a new Index of Globalization. Applied Economics, 38(10), 1091–1110.

Duflo, E. (2001). Schooling and labor market consequences of school construction in indonesia: Evidence from an unusual policy experiment. American Economic Review, 91(4), 795–813.

Elis, R. (2011). Redistribution Under Oligarchy: Trade, Regional Inequality, and the Origins of Public Schooling in Argentina, 1862’1912.

Elkins, Z., Guzman, A., Simmons, B.A. (2006). Competing for capital: the diffusion of bilateral investment treaties, 1960-2000. International Organization, 60, 811–846.

Evans, G., & Rose, P. (2012). Understanding education’s influence on support for democracy in Sub-Saharan africa. Journal of Development Studies, 48(4), 498–515.

Feng, Y. (1997). Democracy, political stability and economic growth. British Journal of Political Science, 27(3), 391–418.

Feng, Y., & Zak, P.J. (1999). The determinants of democratic transitions. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 43(2), 162–177.

Finkel, S.E. (2002). Civic education and the mobilization of political participation in developing democracies. The Journal of Politics, 64(4), 994–1020.

Franzese, R.J, & Hays, J.C. (2008). Hays interdependence in comparative politics: substance, Theory, Empirics, Substance. Comparative Political Studies, 41 (4-5), 742–780.

Galor, O., & Moav, O. (2006). Das human kapital: a theory of the demise of the class structure. The Review of Economic Studies, 73(1), 85–117.

Galor, O., Vollrath, O., Dietrich, M. (2009). Inequality in landownership, the emergence of Human-Capital promoting institutions, and the great divergence. Review of Economic Studies, 76(1), 143–179.

Galston, W.A. (2001). Political knowledge, political engagement,and civic education. Annual Review of Political Science, 4, 217–234.

Gandhi, J., & Przeworski, A. (2006). Cooperation, cooptation, and rebellion under dictatorships. Economics & Politics, 18(1), 1–26.

Gandhi, J., & Przeworski, A. (2007). Authoritarian Institutions and the Survival of Autocrats. Comparative Political Studies, 40(11), 1279–1301.

Geddes, B. (1999). Authoritarian breakdown: Empirical test of a game theoretic argument. In Annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Vol. 2. Atlanta.

Geddes, B, Frantz, J., Erica, W. (2014). Autocratic breakdown and regime transitions: a new data set. Perspectives on Politics 12(1).

Gibson, J.L., Tedin, R.M., Duch, K.L. (1992). Democratic values and the transformation of the Soviet-Union. Journal of Politics, 54(2), 329–371.

Gift, T., & Wibbels, E. (2014). Reading, writing, and the regrettable status of education research in comparative politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 17 (1), 291–312.

Gilardi, F. (2010). Who Learns from What in Policy Diffusion Processes? American Journal of Political Science, 54(3), 650–666.

Glaeser, E.L., La Porta, R., Lopez-de Silanes, F., Shleifer, A. (2004). Do Institutions Cause Growth? Journal of Economic Growth, 9(3), 271–303.

Glaeser, E.L., Ponzetto, G.A.M., Shleifer, A. (2007). Why does democracy need education? Journal of Economic Growth, 12(2), 77–99.

Gleditsch, K.S. (2002). Expanded trade and GDP data. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 46(5), 712–724.

Goldberg, P.N. (2007). Pavcnik distributional effects of trade liberalization in developing countries. Journal of Economic Literature, 45(1), 39–82.

Grant, T., & Lebo, M.J. (2016). Error correction methods with political time series. Political Analysis, 24(1), 3–30.

Gygli, S., Haelg, F., Sturm, J.-E. (2018). The KOF globalisation index: Revisited. KOF working paper No.439.

Gylfason, T. (2001). Natural resources, education, and economic development. European Economic Review, 45(4-6), 847–859.

Hecock, R. (2006). Douglas Electoral competition, globalization, and subnational education spending in Mexico, 1999–2004. American Journal of Political Science, 50 (4), 950–961.

Helliwell, J.F. (1994). Empirical linkages between democracy and Economic-Growth. British Journal Of Political Science, 24, 225–248.

Henn, C., Papageorgiou, C., Spatafora, N. (2015). Export quality in advanced and developing economies: Evidence from a new dataset Technical report World Trade Organization (WTO), Economic Research and Statistics Division.

Hong, J.Y. (Forthcoming). How Natural Resources Affect Authoritarian Leaders’ Provision of Public Services: Evidence from China. The Journal of Politics.

Huber, E., Mustillo, T., Stephens, J.D. (2008). Politics and social spending in Latin America. The Journal of Politics, 70(2), 420–436.

Im, K.S., Pesaran, M.H., Shin, Y. (2003). Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics, 115(1), 53–74.

Kadera, K.M., Crescenzi, M.J.C., Shannon, M.L. (2003). Democratic survival, peace and war. American Journal of Political Science, 47(2), 234–247.

Kaufman, R.R., & Segura-Ubiergo, A. (2001). Globalization, domestic politics, and social spending in Latin America. World Politics, 53(4), 553–87.

Keele, L., Linn, S., McLaughlin Webb, C. (2016). Erratum for Keele, Linn, and Webb, (2016). Political Analysis.

Kosack, S. (2013). The logic of Pro-Poor policymaking: Political entrepreneurship and mass education. British Journal of Political Science, pp. 1–36.

Krueger, A.B., & Lindahl, M. (2001). Education for Growth: Why and For Whom? Journal of Economic Literature, 39(4), 1101–1136.

Kurtz, M.J., & Brooks, S.M. (2011). Conditioning the resource curse: globalization, Human Capital, and Growth in Oil-Rich Nations. Comparative Political Studies, 44(6), 747–770.

Larreguy, H, Montiel, C.E., Querubin, O.P. (2017). Political Brokers: Partisans or Agents? Evidence from the Mexican Teachers’ Union. American Journal of Political Science, 61(4), 877–891.

Lebo, M.J., & Grant, T. (2016). Equation balance and dynamic political modeling. Political Analysis, 24(1), 69–82.

Levin, A., Lin, C.F., Chu, C.S.J. (2002). Unit root tests in panel data: Asymptotic and finite-sample properties. Journal of Econometrics, 108(1), 1–24.

Levine, R., & Renelt, D. (1992). A sensitivity analysis of Cross-Country growth regressions. The American Economic Review, 82(4), 942–963.

Levitsky, S., & Way, L. (2002). The rise of competitive authoritarianism. Journal of democracy, 13(2), 51–65.

Lindert, P.H. (2004). Growing public social spending and economic growth since the eighteenth century. New York: Cambridge University Press.

López-Cariboni, S., & Cao, X. (2015). Import competition and policy diffusion. Politics & Society, 43(4), 471–502.

Lucas, R.E. Jr. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of monetary economics, 22(1), 3–42.

Mankiw, N.G., Romer, D., Weil, D.N. (1992). Gregory a contribution to the empirics of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(2), 407–437.

Marshall, M.G., Jaggers, K., Gurr, T.R. (2011). Polity IV project: Dataset users’ manual. Center for Systemic Peace, Polity IV Project.

Miller, M.K. (2012). Economic development, violent leader removal, and democratization. American Journal of Political Science, 56(4), 1002–1020.

Morrison, K.M. (2009). Oil, nontax revenue, and the redistributional foundations of regime stability. International Organization, 107–138.

Mulligan, C.B., Gil, R., Sala-i Martin, X. (2004). Do Democracies Have Different Public Policies than Nondemocracies? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18 (1), 51–74.

Nooruddin, I., & Simmons, J.W. (2009). Openness, uncertainty, and social spending: Implications for the Globalization-Welfare state debate. International Studies Quarterly, 53(3), 841–866.

Papaioannou, E., & Siourounis, G. (2008). Economic and social factors driving the third wave of democratization. Journal of Comparative Economics, 36(3), 365–387.

Przeworski, A., Alvarez, M.E., Limongi, J.A., Fernando, C. (2000). Democracy and development: Political institutions and Well-Being in the world, (pp. 1950–1990). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Reiter, D. (2001). Does Peace Nurture Democracy?. The Journal of Politics, 63(3), 935–948.

Reuter, O.J., & Robertson, G.B. (2015). Legislatures, cooptation, and social protest in contemporary authoritarian regimes. The Journal of Politics, 77(1), 235–248.

Romer, P.M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), S71–S102.

Ross, M. (2006). Is democracy good for the poor ? American Journal of Political Science, 50(4), 860–874.

Ross, M.L. (2012). The Oil Curse. How Petroleum Wealth Shapes the Development of Nations, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Rousseau, D.L., Gelpi, C., Reiter, D., Huth, P.K. (1996). Assessing the dyadic nature of the democratic peace, 1918-88. American Political Science Review, 90(03), 512–533.

Rudra, N. (2004). Openness, welfare spending, and inequality in the developing world. International Studies Quarterly, 48(3), 683–709.

Rudra, N., & Haggard, S. (2005). Globalization, democracy, and effective welfare spending in the developing world. Comparative Political Studies, 38(9), 1015–1049.

Sala-i Martin, X., Doppelhofer, G., Miller, R.I. (2004). Determinants of Long-Term growth: a bayesian averaging of classical estimates (BACE) approach. The American Economic Review, 94(4), 813–835.

Sanborn, H., & Thyne, C. (2014). Learning Democracy: Education and the Fall of Authoritarian Regimes. British Journal of Political Science, 44(4), 773–797.

Schedler, A. (2006). Electoral authoritarianism: The dynamics of unfree competition.

Sianesi, B., & Van Reenen, J. (2003). The returns to education: Macroeconomics. Journal of Economic Surveys, 17(2), 157–200.

Simmons, B.A. (2004). Zachary elkins the globalization of liberalization: Policy diffusion in the international political economy. American Political Science Review, 98, 171–189.

Simmons, B.A., Dobbin, F., Garrett, G. (2006). Introduction: The international diffusion of liberalism. International Organization, 60, 781–810.

Smith, B. (2005). Life of the party: The origins of regime breakdown and persistence under single-party rule. World Politics, 57(03), 421–451.

Stasavage, D. (2005). Democracy and education spending in africa. American Journal of Political Science, 49(2), 343–358.

The World Bank. (2012). World development indicators. Washington: The World Bank (producer and distributor).

Verba, S., Nie Nie, N.H., Kimw, J.-O. (1978). Participation and political equality: A seven-nation comparison, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Wantchekon, L., Novta, N., Klašnja, M. (2012). Education and Human Capital Externalities: Evidence from Colonial Benin.

Ward, H., & Cao, X. (2012). Domestic and international influences on green taxation. Comparative Political Studies, 45(9), 1075–1103.

Way, C.R. (2005). Political insecurity and the diffusion of financial market regulation. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 598, 125–144.

Webber, D. (2002). Policies to stimulate growth: should we invest in health or education? Applied Economics, 34(13), 1633–1643.

Wibbels, E., & Ahlquist, J.S. (2011). Development, trade, and social insurance. International Studies Quarterly, 55(1), 125–149.

Wright, J. (2008). Do authoritarian institutions constrain? how legislatures affect economic growth and investment. American Journal of Political Science, 52(2), 322–343.

Wright, J., & Escriba-Folch, A. (2012). Authoritarian institutions and regime survival: Transitions to democracy and subsequent autocracy. British Journal of Political Science, 42, 283–309.

Zagha, R., & Nankani, G.T. (2005). Economic Growth in the 1990s: Learning from a Decade of Reform. World Bank Publications.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

López-Cariboni, S., Cao, X. When do authoritarian rulers educate: Trade competition and human capital investment in Non-Democracies. Rev Int Organ 14, 367–405 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-018-9311-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-018-9311-x