Abstract

Background

Although upper-extremity disability has been shown to correlate highly with various psychosocial aspects of illness (e.g., self-efficacy, depression, kinesiophobia, and pain catastrophizing), the role of language in musculoskeletal health status is less certain. In an English-speaking outpatient hand surgery office setting, we sought to determine (1) whether a patient’s primary native language (English or Spanish) is an independent predictor of upper-extremity disability and (2) whether there are any differences in the contribution of measures of psychological distress to disability between native English- and Spanish-speaking patients.

Methods

A total of 122 patients (61 native English speakers and 61 Spanish speakers) presenting to an orthopaedic hand clinic completed sociodemographic information and three Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)-based computerized adaptive testing questionnaires: PROMIS Pain Interference, PROMIS Depression, and PROMIS Upper-Extremity Physical Function. Bivariate and multivariable linear regression modeling were performed.

Results

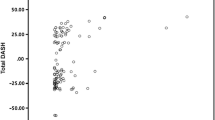

Spanish-speaking patients reported greater upper-extremity disability, pain interference, and symptoms of depression than English-speaking patients. After adjusting for sociodemographic covariates and measures of psychological distress using multivariable regression modeling, the patient’s primary language was not retained as an independent predictor of disability. PROMIS Depression showed a medium correlation (r = −0.35; p < 0.001) with disability in English-speaking patients, while the correlation was large (r = −0.52; p < 0.001) in Spanish-speaking patients. PROMIS Pain Interference had a large correlation with disability in both patient cohorts (Spanish-speaking: r = −0.66; p < 0.001; English-speaking: r = −0.77; p < 0.001). The length of time since immigration to the USA did not correlate with disability among Spanish speakers.

Conclusion

Primary language has less influence on symptom intensity and magnitude of disability than psychological distress and ineffective coping strategies. Interventions to optimize mood and to reduce pain interference should be considered in patients of all nationalities.

Type of study/level of evidence: Prognostic II.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Amtmann D, Cook KF, Jensen MP, et al. Development of a PROMIS item bank to measure pain interference. Pain. 2010;150(1):173–82.

Becker H, Stuifbergen A, Lee H, et al. Reliability and validity of PROMIS cognitive abilities and cognitive concerns scales among people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2014;16(1):1–8.

Bhargava A, Wartak SA, Friderici J, et al. The impact of Hispanic ethnicity on knowledge and behavior among patients with diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2014;40(3):336–43.

Blank SJ, Grindler DJ, Schulz KA, et al. Caregiver quality of life is related to severity of otitis media in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151(2):348–353.

Bot AG, Doornberg JN, Lindenhovius AL, et al. Long-term outcomes of fractures of both bones of the forearm. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(6):527–32.

Carrasquillo O, Orav EJ, Brennan TA, et al. Impact of language barriers on patient satisfaction in an emergency department. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(2):82–7.

Chakravarty EF, Bjorner JB, Fries JF. Improving patient reported outcomes using item response theory and computerized adaptive testing. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(6):1426–31.

De Das S, Vranceanu AM, Ring DC. Contribution of kinesophobia and catastrophic thinking to upper-extremity-specific disability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(1):76–81.

Doornberg JN, Ring D, Fabian LM, et al. Pain dominates measurements of elbow function and health status. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(8):1725–31.

Doring AC, Nota SP, Hageman MG, et al. Measurement of upper extremity disability using the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(6):1160–5.

Fiscella K, Franks P, Doescher MP, et al. Disparities in health care by race, ethnicity, and language among the insured: findings from a national sample. Med Care. 2002;40(1):52–9.

Flynn PM, Ridgeway JL, Wieland ML, et al. Primary care utilization and mental health diagnoses among adult patients requiring interpreters: a retrospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(3):386–91.

Freedman KB, Bernstein J. The adequacy of medical school education in musculoskeletal medicine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(10):1421–7.

Hacker K, Choi YS, Trebino L, et al. Exploring the impact of language services on utilization and clinical outcomes for diabetics. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38507.

Hays RD, Spritzer KL, Amtmann D, et al. Upper-extremity and mobility subdomains from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) adult physical functioning item bank. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(11):2291–6.

Hung M, Baumhauer JF, Brodsky JW, et al. Psychometric comparison of the PROMIS physical function CAT with the FAAM and FFI for measuring patient-reported outcomes. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35(6):592–599.

Hung M, Nickisch F, Beals TC, et al. New paradigm for patient-reported outcomes assessment in foot & ankle research: computerized adaptive testing. Foot Ankle Int. 2012;33(8):621–6.

Hung M, Stuart AR, Higgins TF, et al. Computerized Adaptive Testing using the PROMIS physical function item bank reduces test burden with less ceiling effects compared to the short musculoskeletal function assessment in orthopaedic trauma patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2013. doi:10.1097/BOT.0000000000000059

Lavernia CJ, Lee D, Sierra RJ, et al. Race, ethnicity, insurance coverage, and preoperative status of hip and knee surgical patients. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(8):978–85.

Lindenhovius AL, Buijze GA, Kloen P, et al. Correspondence between perceived disability and objective physical impairment after elbow trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(10):2090–7.

Macintyre S, Hunt K. Socio-economic position, gender and health: how do they interact? J Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):315–34.

Marmot MG, Syme SL. Acculturation and coronary heart disease in Japanese-Americans. Am J Epidemiol. 1976;104(3):225–47.

McCaffery KJ, Holmes-Rovner M, Smith SK, et al. Addressing health literacy in patient decision aids. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13 Suppl 2:S10.

Menendez ME, Bot AG, Hageman MG, et al. Computerized adaptive testing of psychological factors: relation to upper-extremity disability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(20):e149.

Niekel MC, Lindenhovius AL, Watson JB, et al. Correlation of DASH and QuickDASH with measures of psychological distress. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2009;34(8):1499–505.

Ornelas IJ, Perreira KM. The role of migration in the development of depressive symptoms among Latino immigrant parents in the USA. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(8):1169–77.

Peterson PN, Campagna EJ, Maravi M, et al. Acculturation and outcomes among patients with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5(2):160–6.

Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, et al. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS(R)): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment. 2011;18(3):263–83.

Ponce NA, Hays RD, Cunningham WE. Linguistic disparities in health care access and health status among older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(7):786–91.

Potochnick SR, Perreira KM. Depression and anxiety among first-generation immigrant Latino youth: key correlates and implications for future research. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(7):470–7.

Rhodes SD, Martinez O, Song EY, et al. Depressive symptoms among immigrant Latino sexual minorities. Am J Health Behav. 2013;37(3):404–13.

Ring D, Kadzielski J, Fabian L, et al. Self-reported upper extremity health status correlates with depression. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(9):1983–8.

Vega WA, Amaro H. Latino outlook: good health, uncertain prognosis. Annu Rev Public Health. 1994;15:39–67.

Wartak SA, Friderici J, Lotfi A, et al. Patients’ knowledge of risk and protective factors for cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(10):1480–8.

Woolf AD, Erwin J, March L. The need to address the burden of musculoskeletal conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26(2):183–224.

Conflict of Interest

Mariano E. Menendez declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Kyle R. Eberlin declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Chaitanya S. Mudgal declares that he has no conflict of interest.

David Ring declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects, and all identifying details have been omitted from publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Menendez, M.E., Eberlin, K.R., Mudgal, C.S. et al. Language barriers in Hispanic patients: relation to upper-extremity disability. HAND 10, 279–284 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11552-014-9697-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11552-014-9697-8