Abstract

Most adolescents successfully adjust to common school transitions, but face some psychological risks. We explored the subjective social status trajectory of incoming high school freshmen and the impact of extraversion on it. Through a longitudinal design we surveyed 177 participants (using Extraversion and Subjective Social Status Questionnaires) four times: during orientation week and thereafter monthly. The status of the freshmen rapidly declined during the first month and later stabilized. Extraversion had a significant positive relationship with the initial status, and significantly mitigated its decline during the first month. Educators and parents should prioritize freshmen with low externalizing tendencies, by helping them identify their strengths and reduce the negative effects of their lower subjective social status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to life course theory, individuals need to make choices and adapt to all the changes they experience in their lives, which means they need to change their thoughts and behaviors, but this change is not always successful (Elder 1998). During adolescence, school transition is a typical experience. Although most individuals make it through this phase successfully, previous research confirms that school transitions pose many psychological challenges for adolescents, who may experience increased loneliness, anxiety, and depression (Benner and Graham 2009; Benner, Boyle and Bakhtiari 2017). Furthermore, while transitioning from middle to high school, students may experience negative academic performance and school burnout (Benner, Boyle and Bakhtiari 2017; Wang et al. 2015). Therefore, it is important to investigate the psychological changes in adolescents during the transition period and their influencing factors to maintain their psychological health and promote academic development.

Subjective Social Status

Subjective social status (SSS) refers to an individual’s subjective judgment of his or her own social rank (Singh-Manoux, Adler and Marmot 2003). Many studies have discussed the positive effects of SSS on mental health, and individuals with high levels of SSS experience more optimism, subjective well-being, and less depression and despair (Singh-Manoux, Adler and Marmot 2003; Hoebel and Lampert 2020; Takahashi et al. 2018). The positive relationship between SSS and adolescent mental health is also supported by many studies, and higher SSS may lower daily stress and anxiety (Rahal et al. 2020; McLaughlin et al. 2012). Furthermore, research found that low SSS may limit academic achievement in students (Destin et al. 2012).

SSS is a perception of status formed by an individual in reference to the surrounding group (Sweeting and Hunt 2014). Therefore, during the transition period, as schools and classes are reconstructed, the middle school students’ reference group changes, which may alter their SSS as well (Cheng et al. 2016; Marsh et al. 2008). This change in status may be an important contributor to changes in mental health.

Cheng et al.’s (2016) study partially corroborates this view. They used a latent growth model to study the trajectory of SSS of 1983 Chinese college freshmen during their first semester of enrollment. The survey was administered beginning the first week of orientation and every four weeks thereafter, for a total of four surveys. They found that the SSS of college freshmen exhibited a staged trajectory during the school transition phase: initial high levels declined rapidly within a month, and leveled off in the following three months. Notably, not everyone has the opportunity to attend college, in China or elsewhere. For new students, getting into a university is proof of excellence. Moreover, university entrance exams in China are a kind of selection test, where only students with good grades are admitted. Therefore, new students who can enter the same university may be more likely to face social comparisons at a level similar to their own. Thus, as the baseline level of social comparison increases, individuals have to work harder to maintain their previous SSS, which often manifests itself as a decline in the SSS of the incoming cohort. Moreover, an increase in the baseline level means that more upward social comparisons are made, and feelings of anxiety or depression also increase. As their results revealed, the college freshmen’s depression levels significantly increased with the declining SSS.

Based on the aforementioned research, it is possible that that high school freshmen may experience a transitional stage in the formation of a new peer group, just as college freshmen do after finishing high school. It is necessary to explore whether the SSS of high school and college freshmen follow the same trajectory during the transition period.

Extraversion and Subjective Social Status

Cheng et al. (2016) reported significant individual differences in both the intercept and slope of the SSS trajectories of college freshmen during the transition period. Thus, the trajectories of SSS of college freshmen are inconsistent and changeable due to individual differences. Unfortunately, they do not seem to have explored the factors that cause such differences in-depth. During the SSS formation process, some individuals manage to establish peer relationships quicker than others in new groups. Considering the relationship between an individual’s SSS and his or her social environment, this is understandable.

A study of social status found that personality, especially extraversion, has a significant impact on the social status of college freshmen (Anderson et al. 2001). However, they measured social status in a peer-evaluated manner, and it may be questionable how well the concept (social status) obtained in such a manner correlates with SSS. Moreover, their study used longitudinal data, but not a latent growth model approach, which may not confirm whether extraverted personality has an effect on the amount of change in social status, or whether their relationship remains only in a cross-sectional design. Therefore, the relationship between extraversion and SSS in the transition phase on campus needs to be studied more in-depth.

Extraversion is a reflection of a person’s social dynamism and dominance (Roberts, Walton and Viechtbauer 2006) and individuals with high extraversion engage in more interpersonal interactions, gaining greater interpersonal influence (Harris et al. 2017). They quickly gain influence in unfamiliar environments and achieve higher objective social status due to their enhanced social skills which enable them to actively display their positive traits (Anderson et al. 2001). Furthermore, adolescents with higher extraversion have higher self-esteem, more peer influence, and less shyness (Erol and Orth 2011; Fogle, Scott Huebner and Laughlin 2002; Kwiatkowska and Rogoza 2019). Thus, those with higher levels of extraversion appear more likely to seek social status and recognition from others (Christiansen and Tett 2013). Overall, extraversion may significantly affect the SSS of high school freshmen, and its positive effects may limit the downtrend of their SSS. This will enable them to navigate their adjustment more smoothly.

Current Research

Considering existing research, we believe that there may be a significant decline in SSS of high school freshmen during the campus transition period; moreover, extraversion may attenuate the downtrend in SSS. We will first examine the trajectory of SSS changes among high school freshmen, and second, the possible role of extraversion in SSS changes, with reference to the study by Cheng et al. (2016). Finally, with reference to previous studies, we planned to use the Extraversion subscale of the Neuroticism Extraversion Openness Five-Factor Inventory to measure the level of extraversion of high school freshmen (Lemoine et al. 2016; Ong et al. 2011). The specific research hypotheses are as follows:

-

H1, the SSS of high school freshmen shows fragmented changes during the transition period, with a significant decline in the first month of school and a gradual levelling off afterwards.

-

H2, high school freshmen with higher scores on extraversion have a higher SSS at entry. Specifically, extraversion positively predicts the intercept (initial level) of their SSS change trajectory; additionally, extraversion positively affects the slope (rate of change) of their SSS.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Upon the approval of the Academic Ethics Review Committee of the School of Psychology, participants were recruited among freshmen from one high school in southwest China, in fall 2018. All participants including their parents and teachers signed informed consent. At the same time, participants could choose to withdraw at any time, without any negative consequences. Participants were paid ¥10 after each survey.

In the first week of the new term, 177 freshmen (female = 59.9%; male = 40.1%), aged 14 to 17 years (Mage = 15.49, SDage = 0.50) completed the initial survey (SSS, extraversion, and demographic questions). The whole group completed the survey in one sitting. To match the follow-up survey, participants needed to fill in their names. In the initial survey, the subjects recalled and recorded the SSS they had experienced in the previous school. They filled out measures of SSS on three more occasions, one month (T2), two months (T3), and three months later (T4), all from the initial measurement. The number of missing participants per survey were, T2: N = 9, T3: N = 20, and T4: N = 25. A preliminary analysis to compare the initial measurement for the effects of the missing data indicated no significant difference in SSS (t = −0.42, df = 175, p = .68), extraversion (t = 1.79, df = 175, p = .07), or gender (χ2 = 2.10, df = 1, p = .15) at T1. This indicated that the data was missing at random.

Measures

Subjective Social Status

We measured SSS with the 7-item Subjective Social Status Questionnaire for Chinese adolescents (Liu et al. 2017), which was adapted from the Subjective Social Status Questionnaire for College Students (SSSQC) (Cheng et al. 2015). The SSSQC uses a 10-rung “ladder” to measure SSS. For example, for “What was your personal academic achievement in the junior high school where you were studying at (Please be careful not to compare only with friends around you)?” the top ladder is students with the best academic performance in school. Higher scores indicate higher SSS. This scale has demonstrated very good internal consistency (αT1 = 0.79, αT2 = 0.91, αT3 = 0.90, and αT4 = 0.90). The total score was used.

Extraversion

We measured Extraversion using the 12-item Chinese version of Neuroticism Extraversion Openness Five-Factor Inventory (Yao and Liang 2010), which was adapted from McCrae and Costa (2004). Example item: “I like a lot of people around me.” The NEO-FFI uses a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicate higher Extraversion. This scale has demonstrated very good internal consistency (α = 0.83); we used the total score.

Data Analysis

To examine individual trajectories of SSS, we employed univariate Latent Growth Modeling (LGM) for the four repeated measures of SSS, utilizing Mplus Version 7.4 (Linda and Bengt 2012). Next, referring to the research of Cheng et al. (2016), we compared three LGMs with varying model specifications (linear, quadratic, and piecewise linear). Previous studies indicated the social status of freshmen stabilized in approximately one month (Anderson et al. 2001; Cheng et al. 2016). Therefore, the present study could choose a break point in time 2 for a piecewise linear LGM, slope variable captured linear change from baseline to month two (slope1: T1-T2), and the second linear relationship reflected linear changes from month two to four (slope2: T2-T4). Then we sought the best fit model based on the lower value for Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) for a linear trend. Following the recommendations of Bollen and Stine (1992), this study used a variety of global fit indices, including indices of absolute and relative fit (CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and SRMR). Values of SRMR ≤ 0.10, RMSEA ≤ 0.08, CFI ≥ 0.90, and TLI ≥ 0.90 are indicative of an acceptable fit. To explain the variation in the individual trajectories of SSS, we employed conditional LGM, and included individual characteristics (extraversion) as a time-invariant variable. We also performed descriptive analyses and Pearson’s correlations (utilizing SPSS 22.0, Chicago, IL) for all variables. The critical value of the statistical test included p value under the standard .05 level, and 95% bias-correction bootstrap confidence interval. In view of the possible gender differences in SSS, we also included gender in the analysis process when modeling (Freeman et al. 2016).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, and Pearson’s correlations for all variables.

As the contents of Table 1 show that there are significant positive correlations among the scores of SSS and extraversion for all the fourth and significant negative correlations are observed among the gender and scores of SSS. The ratio of skewness (kurtosis) to its standard error is less than +2 or greater than −2. That could conclude: all the scores of SSS and extraversion seem to satisfy the distribution of normality (Mardia 1970). Then, LGMs are handled using Full Information Maximum likelihood (FIML) with missing data.

Unconditional LGM Model

Table 2 shows the linear, quadratic and piecewise linear LGM fit index for SSS (T1-T4). Results from AIC and BIC indicate that quadratic and piecewise linear LGM provide the best fit for SSS over the four months. There is a perfect fit in quadratic LGM, but we are unsure whether this result is only applicable to the current sample; it may mean over fitting. Moreover, from the average of the four surveys, the slope between the SSS T1 and T2 is very large, and then tends to flatten, reflecting the trajectory of a line segment rather than a curve. Combining the theory with the actual situation of data, the piecewise linear LGM is a better choice. Since only two-time points are involved in the first growth segment, we set the covariance between intercept and slope1 in the first growth segment to 0 for model identification (Wang and Wang 2020).

The intercept of SSS and its variance were both significant (p < .01), which indicated that on average, the predicted level of SSS was 43.75 (SE = 0.64, 95%CI [42.50, 44.94]) at T1 and participants varied in their initial status of SSS (Var = 57.72, SE = 7.89, 95%CI [43.43, 75.46]). The slope1 of SSS (Meanslope1 = −4.26, SE = 0.62, p < .01, 95%CI [−5.45, −3.00]) and its variance is also significant (Var = 27.78, SE = 9.88, p < .01, 95%CI [10.78, 50.48]), indicating that on average, the level of SSS decreases by −4.26 points and participants vary in their rate of change over the month. The slope2 (Meanslope2 = −0.32, SE = 0.27, p = .23, 95%CI [−0.86, 0.19]) and its variance (Var = 3.66, SE = 3.27, p = .26, 95%CI [−2.90, 10.07]) was not significant. Lastly, the covariance of the intercept and slope2 was significant (r = −7.11, SE = 2.23, p < .01, 95%CI [−11.67, −3.08]), and the slope1 and slope2 was not significant (r = 1.52, SE = 4.01, p = .71, 95%CI [−7.62, 8.42]).

Conditional LGM Model

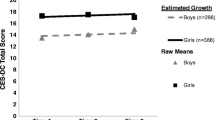

The conditional LGM provides a satisfactory fit to the data, χ2 (4) = 5.30, CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.04; SRMR = 0.01. The extraversion significantly predict the intercept of SSS (βextraversion1 = 0.36, SE = 0.09, p < .01, 95%CI [0.18, 0.53]), indicating that students with high extraversion tend to report high baseline SSS. There is a significant association between extraversion and slope1 of SSS (βextraversion2 = 0.23, SE = 0.09, p = .02, 95%CI [0.05, 0.40]), indicating that students with high extraversion tend to show shallower rate of decrease in SSS. Gender and the intercept of SSS have no significant relationship (βgender1 = −2.30, SE = 1.23, p = .06, 95%CI [−4.83, 0.04]), and the slope1 and slope2 of SSS, too (βgender2 = −2.10, SE = 1.18, p = 0.07, 95%CI [−4.68, 0.09]; βgender3 = −0.74, SE = 0.54, p = .17, 95%CI [−1.76, 0.37]) (see Fig. 1).

Discussion

First, this study’s results are in some ways very similar to Cheng et al.’s (2016) research about college freshmen. Based Cheng et al.'s (2016) view of the trajectory of SSS changes among college freshmen and the results of our study, we infer that: after intense competition for high school entrance exams, high school freshmen of roughly equal level are assigned to the same classes, which can exacerbate homogeneity within classes. Thus, the gap between the abilities of new peers and individuals in the new class is narrowed relative to the familiar class environment of the past, which may threaten their self-efficacy. Marsh et al. (2008) argues that when an individual’s frame of reference for self-evaluation changes, especially when the level of reference increases, he or she develops a negative social comparison that lowers self-evaluation. Therefore, the increase in group homogeneity may be an important reason for the decline in the SSS of high school freshmen. In addition, the critical period for SSS change of high school freshmen is consistent with the findings of college students: in the first month after enrollment (Cheng et al. 2016). This indicates that the critical period for their adjustment to school is not long.

Second, the results of the unconditional LGM showed significant individual differences in both the initial level and rate of change, in SSS of high school freshmen during the transition period. To further explore the reasons for these differences, we constructed conditional LGM by adding extraversion as an independent variable, and found that extraversion significantly affected the initial level of SSS. This result is consistent with previous research (Anderson et al. 2001; Bucciol, Cavasso and Zarri 2015), and as mentioned earlier, individuals with higher extraversion have higher social influence.

In addition, we also found that the higher the extraversion, the slower the decline in SSS of individuals. Combined with the results of the cross-sectional study, extraversion has both an enhancing and protective effect on an individual’s SSS. This may be attributed to the following two factors:

First, individuals with high extraversion will choose more downward social comparisons and maintain higher levels of self-esteem (Olson and Evans 1999; Vaughan-Johnston et al. 2020; Tan, Krishnan and Lee 2017). Previous research has shown that the two main forms of social comparison - upward social comparison and downward social comparison - help individuals achieve self-enhance (Buunk and Gibbons 2007; Gerber, Wheeler and Suls 2018), individuals who prefer upward social comparisons generally have higher motivation for self-improvement and are interested in completing tasks they are good at (e.g., studying). Research with college students found that individuals who preferred upward social comparison had better academic performance at the end of the semester (Blanton et al. 1999). However, upward social comparison also poses a threat to an individual’s ego (Muller and Fayant 2010). It has been shown that more upward social comparisons tend to mean lower self-esteem and subjective well-being (Wang et al. 2017). In contrast, downward social comparisons may imply more positive emotions, higher self-esteem, and greater subjective well-being (Morry, Sucharyna and Petty 2018; Fardouly, Pinkus and Vartanian 2017). Particularly, when individuals face self-threats, downward social comparison leads to greater self-esteem, and the higher the individual’s level of extraversion, the more this benefit increases (Vaughan-Johnston et al. 2020). Previous research has suggested that the core characteristic of extraversion is social competence, but some researchers have suggested that the core traits of extraversion may be positive emotions and reward sensitivity (Lucas, Le and Dyrenforth 2008). Namely, individuals who are extraverted are actively engaged in social interaction for the purpose of gaining more positive emotions. In this regard, downward social comparison coping strategies are likely to be the primary choice for highly extroverted high school freshmen.

Second, individuals with high extraversion tend to have more social support (Zhang 2020). Eysenck’s (1963) extraversion theory argues that extraverted individuals have higher physiological arousal and need to engage in more social interactions to balance their physiological impulses than introverted individuals. This means they are accustomed to more proactively seeking social support to cope with the difficulties they encounter (Amirkhan, Risinger and Swickert 1995). Consequently, these individuals have greater social network space, are more likely to have access to and make use of it (Swickert et al. 2002; Udayar, Urbanaviciute and Rossier 2020). Social support, as a positive psychological resource, effectively counteracts the stress of upward social comparisons, slowing the decline in SSS of high school freshmen.

Future Research

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to reveal the trajectory of SSS change among high school freshmen. For those who have been selected for the high school entrance exam, the formation of a new class brings with it an increase in the average level of the reference group, and thus a significant decline in their SSS during the transition to high school. At the same time, the critical period for SSS decline is one month after enrollment. This means that the freshmen may only need one month for subjective peer status to stabilize. Our results suggest that the trajectory of SSS change is consistent across groups between college and high school freshmen. Therefore, similar phenomena may exist in the construction of other types of new groups, including newly formed groups of military recruits or project teams in companies. Further research into the change pattern in individuals during the construction of new groups, is needed.

Second, extraversion plays a protective role in the formation of an individual’s SSS. Various studies have demonstrated that extraverted individuals gain more social connections, social identity, and a sense of belonging (Brown and Sacco 2017; Baumeister and Leary 1995; González Gutiérrez et al. 2005). In terms of social status, research has also confirmed the relationship between extraversion and changes in the social status of college freshmen (Anderson et al. 2001). However, this study is the first to use LGM to explore the relationship between extraversion and the trajectory of changes in SSS among high school freshmen, revealing the protective effect of extraversion on their SSS. Specifically, extraversion helps to slow the decline in SSS.

In light of our findings, we make the following recommendations: First, the initial month of school for new high school students is a critical adjustment period for their SSS. During this period, educators (including related personnel) and parents should provide appropriate and timely counseling or intervention for students with low levels of mental health to help them navigate this risky period. Second, considering the positive effects of extraversion, educators may try to approach extraversion in mental health education for incoming students. Individuals with low extraversion may need more social support to mitigate the negative effects of a rapidly declining SSS. Since they may generate more upward social comparisons, they require increased guidance from parents and teachers. First, to help them discover their strengths and thus re-establish their self-confidence; second, to avoid more frustration in the formation of new groups, which may affect their future development.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, although we used a longitudinal design it indicated that extraversion is predictive of the trajectory of changes in SSS. In the discussion section, however, both explanations for the role of extraversion in SSS are indirect inferences. Future empirical studies need to determine whether both explanations are valid, or which one is more plausible.

Second, this study relied on self-reported methods to measure the variables. Whether one can apply the patterns of SSS change found in this study to the objective peer status formation of middle school students remains an open question; further research in this area can be done in conjunction with peer assessment.

Finally, our study found that the first month after enrollment is critical for SSS changes among incoming freshmen. However, the sampling period for this study limited the time inflection point, raising the question: is it possible that the SSS of new students stabilizes over a shorter period? Future studies will need to employ more intensive follow-up study designs (including daily reporting) to obtain more precise results.

References

Amirkhan, J. H., Risinger, R. T., & Swickert, R. J. (1995). Extraversion: A “hidden” personality factor in coping? Journal of Personality, 63, 189–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00807.x.

Anderson, C., John, O. P., Keltner, D., & Kring, A. M. (2001). Who attains social status? Effects of personality and physical attractiveness in social groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 116–132. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.81.1.116.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497.

Benner, A. D., Boyle, A. E., & Bakhtiari, F. (2017). Understanding students’ transition to high School: Demographic Variation and the Role of Supportive Relationships. Journal of youth and adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0716-2.

Benner, A. D., & Graham, S. (2009). The transition to high school as a developmental process among multiethnic urban youth. Child Development, 80, 356–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01265.x.

Blanton, H., Buunk, B. P., Gibbons, F. X., & Kuyper, H. (1999). When better-than-others compare upward: Choice of comparison and comparative evaluation as independent predictors of academic performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 420–430. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.3.420.

Bollen, K. A., & Stine, R. A. (1992). Bootstrapping goodness-of-fit measures in structural equation models. Sociological Methods & Research, 21, 205–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124192021002004.

Brown, M., & Sacco, D. F. (2017). Greater need to belong predicts a stronger preference for extraverted faces. Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 220–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.08.012.

Bucciol, A., Cavasso, B., & Zarri, L. (2015). Social status and personality traits. Journal of Economic Psychology, 51, 245–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2015.10.002.

Buunk, A. P., & Gibbons, F. X. (2007). Social comparison: The end of a theory and the emergence of a field. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 102, 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.09.007.

Cheng, G., Chen, Y.-H., Guan, Y.-S., & Zhang, D.-J. (2015). On composition of college Students’Subjective social status indexes and their characteristics. Journal of Southwest University (Natural Science Edition), 2015(6), 156–162.

Cheng, G., Zhang, D., Xiao, Y., Guan, Y., & Chen, Y. (2016). The longitudinal effects of subjective social status on depression in Chinese college freshmen transition: A multivariate latent growth approach. Psychological Development and Education. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2016.06.14.

Christiansen, N., & Tett, R. (2013). Handbook of personality at work (applied psychology series). London: Routledge Academic.

Destin, M., Richman, S., Varner, F., & Mandara, J. (2012). “Feeling” hierarchy: The pathway from subjective social status to achievement. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 1571–1579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.06.006.

Elder, G. H. (1998). The life course as developmental theory. Child Development, 69, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06128.x.

Erol, R. Y., & Orth, U. (2011). Self-esteem development from age 14 to 30 years: A longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 607–619. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024299.

Eysenck, H. J. (1963). Biological basis of personality. Nature, 199, 1031–1034. https://doi.org/10.1038/1991031a0.

Fardouly, J., Pinkus, R. T., & Vartanian, L. R. (2017). The impact of appearance comparisons made through social media, traditional media, and in person in women’s everyday lives. Body Image, 20, 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.11.002.

Fogle, L. M., Scott Huebner, E., & Laughlin, J. E. (2002). The relationship between temperament and life satisfaction in early Adolescence: Cognitive and Behavioral Mediation Models. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, 373–392. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021883830847.

Freeman, J. A., Bauldry, S., Volpe, V. V., Shanahan, M. J., & Shanahan, L. (2016). Sex differences in associations between subjective social status and C-reactive protein in young adults. Psychosomatic Medicine, 78(5), 542–551. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000309.

Gerber, J. P., Wheeler, L., & Suls, J. (2018). A social comparison theory meta-analysis 60+ years on. Psychological Bulletin, 144, 177–197. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000127.

González Gutiérrez, J. L., Jiménez, B. M., Hernández, E. G., & Puente, C. P. (2005). Personality and subjective well-being: Big five correlates and demographic variables. Personality and Individual Differences, 38, 1561–1569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.09.015.

Harris, K., English, T., Harms, P. D., Gross, J. J., & Jackson, J. J. (2017). Why are extraverts more satisfied? Personality, social experiences, and subjective well-being in college. European Journal of Personality, 31, 170–186. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2101.

Hoebel, J., & Lampert, T. (2020). Subjective social status and health: Multidisciplinary explanations and methodological challenges. Journal of Health Psychology, 25, 173–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318800804.

Kwiatkowska, M. M., & Rogoza, R. (2019). A modest proposal to link shyness and modesty: Investigating the relation within the framework of big five personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 149, 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.05.026.

Lemoine, G. J., Aggarwal, I., & Steed, L. B. (2016). When women emerge as leaders: Effects of extraversion and gender composition in groups. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(3), 470–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.12.008.

Linda, K. M., & Bengt, O. M. (2012). Mplus statistical analysis with latent variables: User’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Liu, G., Zhang, D., Pan, Y., Ma, Y., & Lu, X. (2017). The effect of psychological Suzhi on problem behaviors in Chinese Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Subjective Social Status and Self-esteem. Frontiers in Psychology, doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01490

Lucas, R. E., Le, K., & Dyrenforth, P. S. (2008). Explaining the extraversion/positive affect relation: Sociability cannot account for extraverts’ greater happiness. Journal of Personality, 76, 385–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00490.x.

Marsh, H. W., Seaton, M., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Hau, K. T., O’Mara, A. J., et al. (2008). The big-fish–little-pond-effect stands up to critical Scrutiny: Implications for Theory, Methodology, and Future Research. Educational Psychology Review, doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-008-9075-6

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (2004). A contemplated revision of the NEO five-factor inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 587–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00118-1.

McLaughlin, K. A., Costello, E. J., Leblanc, W., Sampson, N. A., & Kessler, R. C. (2012). Socioeconomic status and adolescent mental disorders. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 1742–1750. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300477.

Morry, M. M., Sucharyna, T. A., & Petty, S. K. (2018). Relationship social comparisons: Your facebook page affects my relationship and personal well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 83, 140–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.01.038.

Muller, D., & Fayant, M.-P. (2010). On being exposed to superior Others: Consequences of Self-Threatening Upward Social Comparisons. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00279.x

Olson, B. D., & Evans, D. L. (1999). The role of the big five personality dimensions in the direction and affective consequences of everyday social comparisons. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 1498–1508. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672992510006.

Ong, E. Y. L., Ang, R. P., Ho, J. C. M., Lim, J. C. Y., Goh, D. H., Lee, C. S., & Chua, A. Y. K. (2011). Narcissism, extraversion and adolescents’ self-presentation on Facebook. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(2), 180–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.09.022.

Rahal, D., Chiang, J. J., Bower, J. E., Irwin, M. R., Venkatraman, J., & Fuligni, A. J. (2020). Subjective social status and stress responsivity in late adolescence. Stress (Amsterdam, Netherlands), doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890.2019.1626369,

Roberts, B. W., Walton, K. E., & Viechtbauer, W. (2006). Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.1.

Singh-Manoux, A., Adler, N. E., & Marmot, M. G. (2003). Subjective social status: Its determinants and its association with measures of ill-health in the Whitehall II study. Social Science & Medicine, 56, 1321–1333. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00131-4.

Sweeting, H., & Hunt, K. (2014). Adolescent socio-economic and school-based social status, health and well-being. Social Science & Medicine, 1982, 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.037.

Swickert, R. J., Rosentreter, C. J., Hittner, J. B., & Mushrush, J. E. (2002). Extraversion, social support processes, and stress. Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 877–891. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00093-9.

Takahashi, Y., Fujiwara, T., Nakayama, T., & Kawachi, I. (2018). Subjective social status and trajectories of self-rated health status: A comparative analysis of Japan and the United States. Journal of public health (Oxford, England), doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdx158

Tan, C.-S., Krishnan, S. A., & Lee, Q.-W. (2017). The role of self-esteem and social support in the relationship between extraversion and happiness: A serial mediation model. Current Psychology, 36, 556–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9444-0.

Udayar, S., Urbanaviciute, I., & Rossier, J. (2020). Perceived social support and big five personality traits in middle adulthood: A 4-year cross-lagged path analysis. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(2), 395–414.

Vaughan-Johnston, T. I., MacGregor, K. E., Fabrigar, L. R., Evraire, L. E., & Wasylkiw, L. (2020). Extraversion as a moderator of the efficacy of self-esteem maintenance strategies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 47, 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167220921713.

Wang, J., & Wang, X. (2020). Structural equation modeling: Applications using Mplus (2nd edn, Wiley series in probability and statistics). Hoboken NJ: Wiley.

Wang, J.-L., Wang, H.-Z., Gaskin, J., & Hawk, S. (2017). The mediating roles of upward social comparison and self-esteem and the moderating role of social comparison orientation in the association between social networking site usage and subjective well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00771.

Wang, M.-T., Chow, A., Hofkens, T., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2015). The trajectories of student emotional engagement and school burnout with academic and psychological development: Findings from Finnish adolescents. Learning and Instruction, 36, 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.11.004.

Yao, L., & Liang, L. (2010). Analysis of the application of simplified NEO-FFI to undergraduates. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 18(4), 457–459.

Zhang, Z. (2020). Mediation of perceived social support in personality traits and positive coping style among post-2000 college students. China Journal of Health Psychology. https://doi.org/10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2020.08.027.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere thanks to Professor Gang Cheng for his comments and support during the writing of this paper, to the reviewers for their patience in reviewing this paper, and to the editors for their seriousness and responsibility.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support fromResearch project of Humanities and Social Sciences in Colleges and universities of Guizhou Province (Master Program) supported by the Department of Education of Guizhou Province (DEGP, Project No. 31760283) and PhD early development program of Guizhou Normal University (2017) supported by the Guizhou Normal University (GZNU), and awarded from the Special Project for Academic Novice Cultivation and Innovative Exploration (Project No. Qian Ke Quan Ping Tai Ren Cai [2017] 5726-16) supported by Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Foundation (GPSTF).

Funding

This research was funded by the Research project of Humanities and Social Sciences in Colleges and universities of Guizhou Province (Master Program) supported by the Department of Education of Guizhou Province (DEGP, Project No. 31760283); It was also awarded from PhD early development program of Guizhou Normal University (2017) supported by the Guizhou Normal University (GZNU) and awarded from the Special Project for Academic Novice Cultivation and Innovative Exploration (Project No. QianKeQuanPingTaiRenCai[2017]5726–16) supported by Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Foundation (GPSTF). The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in the paper are solely of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of GZNU, DEGP and GPSTF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Jianmei Ye, Dawei Huang, Lei Liu, and Yuelin Li. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Jianmei Ye and Mengwei Shi. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, J., Huang, D., Li, Y. et al. Subjective Social Status of High School Freshmen in the Transitional Period: the Impact of Extraversion. Applied Research Quality Life 17, 971–983 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-021-09945-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-021-09945-3