Abstract

This study investigated the relationships between active, problem-focused, and maladaptive coping with stress during the Coronavirus outbreak, the Big Five personality traits, and social support among Israeli-Palestinian college students (n = 625). Emotion-focused coping negatively correlated with social support, openness, extraversion, conscientiousness, and agreeableness, while it positively correlated with neuroticism. On the other hand, problem-focused coping was found to positively correlate with social support, openness, extraversion, conscientiousness, and agreeableness, but negatively correlate with neuroticism. Thus, positive social support may increase one’s ability to cope actively, adaptively, and efficiently. In addition, Israeli-Palestinian college students high in openness, extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness tend to use active problem-focused coping while those high in neuroticism tend to use maladaptive emotion-focused coping.

Similar content being viewed by others

The current COVID-19 pandemic is substantially changing what is familiar to us in our daily lives. Despite the mass quarantine proposed by many countries beneficially containing the pandemic and reducing the number of people infected with the COVID-19 virus, many are fearing the potential intensification of mental health problems during this period. Since the outbreak started in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, many scholars have begun identifying the negative implications of quarantine on people’s mental health and wellbeing (Brooks et al. 2020). This approach is supported by studies of recent quarantines—such as the 2003 quarantine in Toronto due to SARS (Robertson et al. 2004), the 2014 quarantine in West Africa due to Ebola (Drazen et al. 2014), and the 2015 quarantine in Korea due to MERS (Jeong et al. 2016)—which all show a significant increase in mental health problems among quarantined individuals.

Individuals in crisis are highly prone to experience increased levels of stress, tension, and anxiety. Nevertheless, various types of stressors affect people differently depending on each individual’s coping abilities and capabilities (Byrd and McKinney 2012). Many scholars have thus identified the types of personal (individual) and interpersonal (social) stressors that can be controlled during this period as means to find ways to cope with them. With specific relevance to COVID-19, personal (individual) stressors include confinement, loss of structure and routine, confusion, uncertainty and fear of the unknown, fear of infection, poor concentration, reduced physical activity and exposure to sunlight, sleep disturbances and excessive use of digital media before bedtime, changes in eating patterns, and high consumption of COVID-19-related news and media (Altena et al. 2020; Brooks et al. 2020; Buheji and Ahmed 2020; Cellini et al. 2020; Hiremath et al. 2020; Torales et al. 2020).

Coping Strategies

Coping is a regulatory process that serves to reduce the negative emotional effects of stressful events (van Berkel 2009). Here, coping strategies refer to the methods adopted and practiced by individuals as means to deal with various stressors. Scholars have identified multiple strategies for coping and further examined how these various coping strategies are influenced by intrapersonal, interpersonal, and environmental factors. Consequently, psychologists have distinguished between more than 400 coping strategies (Skinner et al. 2003), and these have been mainly classified either within the “approach-or-avoidance” model (Finset et al. 2002; Roth and Cohen 1986) or the emotion- or problem-focused coping model (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). The most common categories used, nevertheless, fall within the problem- and emotion-focused coping model.

Problem-focused coping is defined as individual efforts to “employ active strategies to resolve the stressors” (Riley and Park 2014). This type of coping is usually employed when individuals feel that something constructive can be done directly to alter the source of their stress (Folkman and Lazarus 1980). Hence, problem-focused coping includes problem-solving strategies and task-oriented actions such as planning, seeking instrumental support, and following through on steps that can directly reduce or resolve the problem (Carver and Connor-Smith 2010; Lazarus and Folkman 1984; Nes and Segerstrom 2006). Research shows that problem-focused coping is usually associated with adaptive outcomes such as better academic performance (MacCann et al. 2011) and higher marital satisfaction (Stoneman et al. 2006). Preliminary studies have also demonstrated that adaptive, problem-focused coping strategies are associated with greater psychological well-being during the COVID-19 quarantine precautions (Fu et al. 2020; Rogowska et al. 2020).

On the other hand, emotion-focused coping includes “processing and expressing feelings arising from the stressor” (Riley and Park 2014). In other words, emotion-focused coping can be defined as the process of employing emotion-based strategies in an attempt to reduce or manage the emotional distress evoked by a situation (Carver and Connor-Smith 2010; Lazarus and Folkman 1984). This can involve adaptive strategies such as reappraising or reinterpreting a stressor as nonthreatening (Lazarus 1993) or attempting to relax using breathing techniques (Nes and Segerstrom 2006). However, emotion-focused coping can also involve maladaptive strategies such as wishful thinking, denial, avoidance, self-blame, and interpersonal withdrawal (Carver and Connor-Smith 2010).

Research tends to show that adaptive forms of emotion-focused coping are associated with positive outcomes (Austenfeld and Stanton 2004), whereas maladaptive forms of emotion-focused coping are associated with a range of negative emotions and cognitions (Carver et al. 1989; Compas et al. 2001;O’Brien and DeLongis 1996). Importantly, initial studies have found that using maladaptive emotion-focused coping strategies during the COVID-19 quarantine period has been related to poorer psychological functioning (e.g., elevated anxiety and depression) (Fu et al. 2020; Rogowska et al. 2020).

Given that individuals react to stress in various ways, understanding the likelihood of coping with stressors adaptively or maladaptively requires an examination of the moderating factors—e.g., individual differences, personality traits and/or social relations—that link individuals to different types of stressors (Chai and Low 2015).

Big Five Personality Traits and Coping Strategies

Students are faced with numerous, unique developmental challenges (e.g., academic performance, career choice, peer acceptance). As such, their ability to cope effectively is crucial under the transactional model of stress developed by Lazarus and colleagues (Lazarus 1966; Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Broad associations observed between personality traits and coping with stress may provide important insight into individual differences in patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving that translate to managing stress through adaptive versus maladaptive coping (Zainah et al. 2019).

The Big Five personality traits are emotional stability/ neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness, and they are viewed as the basic dimensions of personality (Costa and McCrae 2008). The Big Five personality traits refer to the behavioral patterns that individuals with certain personality traits exhibit over time (Ezeakabekwe and Nwankwo 2020). As specified in the socio-genomic model, personality traits are defined as relatively enduring, automatic patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that distinguish individuals from each other (Roberts 2017).

Many researchers have looked into the relationship between coping and the Big Five personality traits (e.g., Connor-Smith and Flachsbart 2007; Costa et al. 1996; Lee-Baggley et al. 2005; McCrae and Costa Jr 1986; O’Brien and DeLongis 1996; Parkes 1986; Penley and Tomaka 2002; Preece, & Delongis; 2005; Watson and Hubbard 1996). Some studies have shown that non-adaptive personality traits like neuroticism are positively associated with avoidance coping (Connor-Smith and Flachsbart 2007; Penley and Tomaka 2002; Watson and Hubbard 1996). In contrast, adaptive personality traits like conscientiousness are positively related to active coping styles (e.g., planning and problem solving) (O’Brien and DeLongis 1996; Watson and Hubbard 1996).

The association between personality traits and coping strategies suggest that individuals with maladaptive personalities are at a greater risk of experiencing psychological distress, as they usually employ maladaptive coping strategies like avoidant coping (Holahan et al. 2005). However, not all findings about the relationship between personality traits and coping strategies are consistent. For instance, some researchers were not able to find a significant relationship between coping and personality traits like agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness (David and Suls 1999; Hooker et al. 1994). Moreover, researches were also unable to find a significant relationship between extraversion and problem-focused coping (Hooker et al. 1994; O’Brien and DeLongis 1996) and between extraversion and adaptive forms of emotion-focused coping, such as seeking support and accepting responsibility (David and Suls 1999; O’Brien and DeLongis 1996). Thus, a more nuanced look at associations with each of the five personality traits is needed to provide context for the present work.

Neuroticism (N)

Neuroticism (N) refers to personalities that are more vulnerable to experiencing emotional instability and self-consciousness (Costa and McCrae 2008). Scholars have found that neuroticism (N) is positively correlated with perceived stress (Mirhaghi and Sarabian 2016). Individuals high in N are prone to experience negative emotions such as depression, anxiety, or anger, and they tend to be impulsive and self-conscious (McCrae 1992; McCrae and Costa Jr. 1987). Therefore, these individuals are generally more prone to experiencing psychological distress as their subversive emotions interfere with their adaptation process. Such subversive emotions are the result of irrational thoughts, less ability to control self-motivation, and deal more negatively with stress (Digman 1989; Digman and Inouye 1986; Mervielde et al. 1995).

In terms of coping strategies, scholars have found that individuals high in N specifically employ avoidance coping more than other strategies (David and Suls 1999; Gunthert et al. 1999; O’Brien and DeLongis 1996; Roesch et al. 2006; Zainah et al. 2019), though maladaptive emotion-focused coping strategies (e.g., substance abuse, behavioral disengagement, venting, and self-blame) are also common (Boyes and French 2010). This is since individuals who are high in N are more susceptible to psychological distress, prone to irrational thoughts, and are less able to control their impulses (Costa and McCrae 1992). In addition to avoidance, neuroticism was also found to be linked to immature coping strategies such as self-blame and fantasizing (Wang and Miao 2009). However, neuroticism (N) has also been related to may be positively related to adaptive emotion-focused coping (e.g., seeking emotional support) (Smith et al. 1989), suggesting some individual variability. Nevertheless, as shown in the literature, neuroticism is most substantially related to maladaptive coping, and one reason for this is that individuals high in N have usually experienced acute fear and traumatic distress (Hengartner et al. 2017).

Extraversion (E)

Extraversion (E) refers to the tendency to be outgoing, prefer large groups and gatherings, and be assertive, active, and talkative. Individuals high in E are found to be highly upbeat, energetic, and optimistic (Digman 1989; Digman and Inouye 1986; Mervielde et al. 1995). Moreover, extraversion reflects the tendency to be gregarious, enthusiastic, and assertive, and to seek excitement. This could be one of the reasons why Extraversion has been found to be negatively correlated with stress and anxiety (Mirhaghi and Sarabian 2016). Yet, like others, individuals high in E experience distress, but they may be able to cope with life’s stressors more effectively than others, in a manner that reduces the negative consequences of experiencing distress.

In terms of coping strategies, previous studies have found that extraversion (E) was positively correlated with active coping strategies, such as problem solving and seeking support (Karimzade and Besharat 2011; Vollrath and Torgersen 2000; Wang and Miao 2009; Zainah et al. 2019). More specifically, Extraversion was found to be positively related to active problem-focused coping (e.g., problem solving and planning) and adaptive emotion-focused coping (e.g., positive reframing, humor, seeking support, and acceptance) (Roesch et al. 2006). This is since individuals who are high in E are usually cheerful and motivated, and thus they often engage in active coping and positive reappraisal (Amirkhan et al. 1995; Costa et al. 1996; e.g., Watson and Clark 1992; Watson and Hubbard 1996). It is noteworthy to mention that some studies have found no relationship between Extraversion and coping (O’Brien and DeLongis 1996). Thus, studying this relationship is still an underdeveloped area of study with potential nuances and individual differences.

Conscientiousness (C)

Conscientiousness (C) refers to the tendency to resist impulses and temptations. Hence, individuals high in C usually strive for dutifulness and competence (Costa and McCrae 2008). Moreover, these individuals are found to be highly purposeful, strong-willed, and determined. On the positive side, individuals high in C are usually associated with academic and occupational achievements, but, on the negative side, these individuals may be drawn to annoying fastidiousness, compulsive neatness, and workaholic behavior (Digman 1989; Digman and Inouye 1986; Mervielde et al. 1995). Nevertheless, Conscientiousness was found to negatively correlate with stress (Mirhaghi and Sarabian 2016). For instance, studies that looked into the relationship between Conscientiousness and occupational stress found that Conscientiousness serves as a protective factor against exhaustion due to prolonged occupational stress (Swider and Zimmerman 2010).

Although Conscientiousness usually correlates negatively with stress anxiety, some studies have found contradictory associations (Scher and Osterman 2002; Sheridan et al. 2015). Vreeke and Muris (2012) found that Conscientiousness served as a positive predictor of behavioral inhibition—a component of anxiety that is characterized by timidity and withdrawal. This suggests that conscientiousness and anxiety may be interrelated and can co-exist in individuals. Furthermore, previous research has indicated that there is a significant interaction between anxious arousal and conscientiousness in predicting ambition. This interaction showed that physically anxious individuals with higher conscientiousness experience higher levels of professional ambition, as compared to physically anxious individuals with lower levels of conscientiousness (Chandra et al. 2020).

This may be because individuals high in Conscientiousness are careful planners and extremely rational decision makers especially in situations where they encounter a stressor (Chartrand et al. 1993; Hooker et al. 1994; Vollrath et al. 1994). In terms of coping strategies, Conscientiousness was found to be positively related to active problem-focused (e.g., planning) and adaptive emotion-focused coping (e.g., positive reframing, humor and acceptance) (Karimzade and Besharat 2011; Leandro and Castillo 2010; Roesch et al. 2006). This is since individuals high in Conscientiousness are purposeful, strong-willed, and determined, and they are deliberate before they act (Costa and McCrae 1992).

Openness (O)

Openness (O) is a cognitive disposition to creativity and esthetics (Costa and McCrae 2008; Zainah et al. 2019). Individuals high in Openness (O) have the tendency to be curious about both their inner and outer worlds. These individuals are found to experience active imagination, esthetic sensitivity, and attentiveness to inner feelings, and they usually display a preference for a variety of things, intellectual curiosity, and independent judgment. These individuals are usually unconventional, willing to question authority, and ready to debate new ethical and social ideas (Digman 1989; Digman and Inouye 1986; Mervielde et al. 1995).

In terms of coping strategies, Openness has been positively related to active problem-focused (e.g., planning) and adaptive emotion-focused coping (e.g., positive reframing, humor, and acceptance) (Chai and Low 2015; McCrae and Costa Jr 1986; Roesch et al. 2006; Watson and Hubbard 1996). This is because individuals high in Openness are curious about both inner and outer worlds, and they are perceived to be more flexible and creative than others. Hence, these individuals are able to cope more effectively than others as they have the capacity to employ multiple coping methods simultaneously to minimize the effects of the stressor and/or the distress experienced (Roesch et al. 2006).

Agreeableness (A)

Lastly, Agreeableness (A) is defined as the tendency to be altruistic, sympathetic to others and eager to help them, and believe that others will be equally helpful in return (Digman 1989; Digman and Inouye 1986; Mervielde et al. 1995). Agreeableness was found to be negatively correlated with stress (Mirhaghi and Sarabian 2016). However, when individuals high in Agreeableness experience stress, they usually employ adaptive coping strategies like active coping and humor. Moreover, Agreeableness has been negatively associated with impulsive behaviors like substance abuse (Hengartner et al. 2017).

Social Support and Coping Strategies

Social support can be defined as providing care, information, assistance, and/or resources to individuals in a manner that facilitates their adaptation to life’s stressors (Cutrona 1996). Social support is an important factor that helps reduce the negative effects of stress. Prior research has shown that social support has the ability to improve physiological and mental health, increase one’s adaptation to chronic diseases, and reduce mortality rates (Umberson and Karas Montez 2010). Additionally, high levels of social support make it easier for the individual to establish better self-esteem, increase the individual’s perception of their ability to cope with the stress, and strengthen the individual’s perception of their capability to solve problems and minimize the severity of stressors (Wang et al. 2014).

Most scholars agree that social networks can act as an invaluable coping resource. This even has specific relevance to members of the Israeli-Palestinian community living in Israel who demonstrate the positive effects of social support, especially when dealing with stressful conditions (Agbaria 2013; Agbaria 2019; Agbaria and Bdier 2019; Agbaria et al. 2017; Agbaria and Natur 2018; Agbaria et al. 2012). Nonetheless, some studies have also suggested that social networks can act as an impediment to adaptive coping. Although attempts to provide social support are usually well intentioned, these attempts are not always perceived as helpful by the recipient (Dakof and Taylor 1990). Also, disappointment with social support may rise due to a perceived lack of support, a failure of support attempts to match the needs of the recipient, or mal-intended interactions with support providers such as including criticism or avoidance (Revenson 1990). Individuals may thus be more likely to engage in maladaptive or counterproductive modes of coping—which can have tremendous negative repercussions on their own well-being—if they perceive that support is lacking from significant others, or when one is dissatisfied with support provided (DeLongis and Holtzman 2005).

The Present Study

This current study is the first to investigate the relationship between coping with stress due to the Coronavirus outbreak, the Big Five personality traits, and social support among Israeli-Palestinian college students (n = 625). This comprehensive examination of the relationship between personality traits and coping with stress may shed light on individual differences relevant to coping with the Coronavirus pandemic. Furthermore, this work will explore the given variables in the unique context of the Palestinian-Israeli minority living in Israel. Importantly, no prior studies have examined these variables within the specific Israeli-Palestinian student population of interest, which highlights the novelty of the present research.

The Israeli-Palestinian minority living in Israel is of particular uniqueness; this community lives as a collective society that is experiencing rapid modernization along with “Israelization” on one hand (Al Hajj 1996) while also experiencing movements in the opposite direction by Islamization and “Palestinianization” (Samoha 2004). In addition to the formal and informal discrimination faced by many minorities, the Israeli-Palestinian community in Israel has to lead a double life as an undesirable ethnic, religious, and political minority living in a Jewish-majority state. Hence, this community has captured itself as a society on the fringes of Israeli society, being disadvantaged in terms of social and health services, along with a lower economic status and lower mental health welfare when compared to the Jewish community living in Israel. This population, thus, faces a unique dichotomy within their own culture that may cause challenges to their identity formation (Ericson 1962; Sue and Sue 2003); this may inform the relationship between individual characteristics and stress coping strategies.

During the Coronavirus crisis, the Israeli-Palestinian community was further marginalized in the public discourse as it does not meet the “priority criteria” in governmental health services. Therefore, this community has been excluded from the general mass COVID-19 tests carried out by the government as well as the public guidelines around the disease (Khoury 2020). Therefore, the question of what support sources Israeli-Palestinians have is significant in the shadow of these conditions. It is unknown how the individual differences of personality traits and social support, which are known to be relevant to adaptive coping during stressful times, may apply to the unique Israeli-Palestinian student population of interest. This research is novel and necessary to better examine who among this potentially marginalized group may be at risk for maladaptive coping strategies during the Coronavirus crisis.

Based on previous research findings, the current study hypothesizes that among Israeli-Palestinian college students in Israel, (1) social support, openness, extraversion, conscientiousness, and agreeableness will be negatively associated with emotion-focused coping; (2) social support, openness, extraversion, conscientiousness, and agreeableness will be positively associated with problem-focused coping; (3) neuroticism will be negatively associated with problem-focused coping; and (4) neuroticism will be positively associated with emotion-focused coping. In addition to these associations, exploratory regression analyses were used to understand how each of the individual characteristics (Big Five personality traits and social support) uniquely relate to the outcomes of coping with stressors using problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping.

Methodology

Sample

The sample consisted of 625 Israeli-Palestinian college students, 72% of whom were females and 28% males. Participants’ ages ranged from 19 to 30 years old (M = 24.8, SD = 5.88). The participants were recruited using non-random convenience sampling from eight colleges in Israel. Sixty-five percent of the participants grew up in villages (rural) and 35% of them grew up in cities (urban). In terms of religious affiliation, 80% of the participants identified as Muslims, 15% identified as Christians, and 5% identified as Druze. This research was conducted at the beginning of the Coronavirus outbreak in order to capture acute associations of individual differences with coping strategies at the onset of this stressful situation.

Measures

Each measure was translated from English to Arabic by five interdisciplinary Israeli-Palestinian scholars. The measures were assessed by the researchers in collaboration with the five experts, and they were checked for the clarity and cultural appropriateness of the content and translation. The questionnaires were then translated back into English by an independent expert in translation. Finally, 40 Israeli-Palestinian students completed the questionnaires and provided feedback on the process.

Demographic Variables Questionnaire

The variables included in this instrument are gender, age, residence, and religion.

Coping Style Questionnaire

This questionnaire is based on Carver, Scheier, and Weintruab’s (1989) questionnaire that was translated into Arabic (Odeh 2014). The Arabic version includes 30 items assessed according to a scale of 1 = not at all and 5 = to a great extent. These items contain variables classified according to problem-focused coping (alpha = .70) and emotion-focused coping (alpha = .67). For example, an item assessing problem-focused coping is (from the English translation): “I try to come up with a strategy about what to do.” All the items were with a load level greater than 0.40.

Big Five Personality Trait Short Questionnaire (BFPTSQ)

The BFPTSQ was developed by John and Srivastava (1999), and it consists of 44 items answered on a five-point Likert-type response format (totally disagree = 1 to totally agree = 5). It assesses the five personality traits: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability/ neuroticism, and openness. In the present study, Cronbach alpha are as follows: extraversion (α = .74), agreeableness (α = .67), conscientiousness (α = .73), neuroticism (α = .75), and openness (α = .72). For example, an item assessing openness (from the English translation) is: “I see myself as someone who is inventive.” All the items were with a load level greater than 0.40.

Social Support Questionnaire

This questionnaire includes 12 items assessing the characteristics of the support system, i.e., the degree of support provided and from which sources, its frequency, and its availability (Cohen and Wills 1985). The questionnaire uses a scale from 1 to 4 (1 = very untypical of me, to 4 = very typical of me). The higher the score, the greater social support received. Reverse items in the social support questionnaire are 1, 2, 7, 8, 11, and 12. The Israeli-Palestinian version of this questionnaire received a high Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α = 0.90) in a study by Agbaria (2014). In the Israeli-Palestinian version, a sample question is: “I feel that there is no one I can share my most private worries and fears with.” In the present study, Cronbach alpha was (α = .87). All the items were with a load level greater than 0.40.

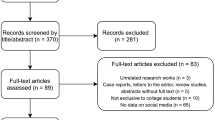

Research Procedure

The study sample was recruited by non-random convenience sampling at eight colleges in Israel. The research was conducted in 2020 over the course of 3 months, i.e., during the beginning of the Coronavirus Outbreak in Israel. After obtaining the needed clearances from each of the colleges as well as the ethical committee at Al-Qasemi College, the questionnaires were distributed using Google forum, stressing that the questionnaires would remain anonymous. Eighty percent of the students who received the questionnaire agreed to participate.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for the study variables (problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, Big Five personality traits, and social support) were examined. Assumptions of normality, homogeneity of variances, linearity, and independence were confirmed, demonstrating the appropriateness of conducting the parametric testing. In order to examine the study hypotheses, two approaches were used. First, bivariate correlations were examined for all study variables. Correlations were considered to have a small effect size if r = |.10–.29|, medium if r = |.30–.49|, and large if r = |.50–.1.00|. Second, linear multiple regression models were employed to test the associations of Big Five personality traits and social support with employing problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. The multiple regression model was used in order to understand how each of the individual characteristics (Big Five personality traits and social support) uniquely relate to the outcomes of coping with stressors using problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping, while also controlling for other independent variables in the model.

Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the study variables. Overall, the students exhibited medium scores in the coping styles questionnaire, medium scores in each of the BFPTSQ sub-scores, and medium-high scores in the social support questionnaire.

Table 2 reveals the correlations between the study variables.

Consistent with the first study hypothesis, there was a significant negative correlation between emotion-focused coping scores and social support (r = −.40, p < .01), BFPTSQ openness (r = −.30, p < .01), BFPTSQ extraversion (r = −.32, p < .01), BFPTSQ conscientiousness (r = −.33, p < .01), and BFPTSQ agreeableness (r = −.34, p < .01).

The regression model (Table 3) found that social support explains the significant amount of variance in emotion-focused coping scores (β = −.22, p < 0.01), as did BFPTSQ openness (β = −.19, p < 0.01), BFPTSQ extraversion (β = −.22, p < 0.01), BFPTSQ conscientiousness (β = −.22, p < 0.01), and BFPTSQ agreeableness (β = −.20, p < 0.01).

Consistent with the second study hypothesis, there was a significant positive correlation between problem-focused coping scores and social support (r = .32, p < .01), BFPTSQ openness (r = .36, p < .01), BFPTSQ extraversion (r = .39, p < .01), BFPTSQ conscientiousness (r = .37, p < .01), and BFPTSQ agreeableness (r = .31, p < .01).

The regression model (Table 4) found that social support also explains the significant amount of variance in problem-focused coping scores (β = .19, p < 0.01), as did BFPTSQ openness (β = .16, p < 0.01), BFPTSQ extraversion (β = .18, p < 0.01), BFPTSQ conscientiousness (β = .21, p < 0.01), and BFPTSQ agreeableness (β = .18, p < 0.01).

Consistent with the third study hypothesis, there was a significant negative correlation between problem-focused coping scores and BFPTSQ neuroticism (r = −.36, p < .01). The regression model (Table 4) found that BFPTSQ neuroticism explains the significant amount of variance in problem-focused coping scores (β = −.23**, p < 0.01).

Consistent with the fourth study hypothesis, there was a significant positive correlation between emotion-focused coping scores and BFPTSQ neuroticism (r = .42, p < .01). The regression model (Table 4) found that BFPTSQ neuroticism also explains the significant amount of variance in emotion-focused coping scores (β = .22, p < 0.01).

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between coping with stress, the Big Five personality traits, and social support among Israeli-Palestinian college students in order to help elucidate the individual characteristics that may assist students while coping with stressful conditions. The results show that adaptive personality traits (openness, extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness) were positively correlated with problem-focused coping and negatively correlated with emotion-focused coping, whereas maladaptive personality traits (neuroticism) were negatively correlated with problem-focused coping and positively correlated with emotion-focused coping. Furthermore, the results of this study demonstrate that openness and conscientiousness have the most significant positive correlation with problem-engagement as an active problem-focused coping strategy, while extraversion and agreeableness have the most significant positive correlation with positive reinterpretation and growth. These findings add important insight to preliminary research demonstrating that adaptive coping strategies lead to more favorable psychosocial outcomes during COVID-19 by highlighting the individual differences among Israeli-Palestinian students that may enhance risk for poorer psychological functioning during this time.

Big Five Personality Traits and Coping Styles

Consistent with previous research, individuals with greater openness, extraversion, conscientiousness, and agreeableness were found to be more likely to employ more problem-focused coping and less maladaptive emotion-focused coping, whereas those with greater neuroticism were found to be less likely to employ problem-focused coping and more likely to employ maladaptive emotion-focused coping.

Openness was found to be positively related to problem-focused coping and negatively related to emotion-focused coping, which is consistent with prior findings that demonstrate the importance of openness for adaptive coping (Chai and Low 2015; Penley and Tomaka 2002), which may be explained by Openness including curiosity about both inner and outer worlds, and thus individuals who score high in the Openness measure are more flexible and creative than others. Additionally, individuals who score high in the Openness measure experience their emotions in a comfortable manner, as they are able to accept their emotions as well as others’ emotions better. This suggests that these individuals are able to cope with stress flexibly by using multiple coping strategies to minimize the negative effects of stressor and/or the distress experienced (Roesch et al. 2006). Therefore, these individuals tend to use problem-focused coping more often than emotion-focused coping (Leandro and Castillo 2010; Suls et al. 1998).

Extraversion was also found to be positively related to problem-focused coping and negatively related to emotion-focused coping, which is consistent with previous studies that highlight the importance of extraversion for adaptive coping (Karimzade and Besharat 2011; Roesch et al. 2006; Wang and Miao 2009; Zainah et al. 2019). These findings can be explained by considering how individuals who score high in the extraversion measure are usually drawn towards excitement and optimism. When facing a stressful situation or event, these individuals employ coping strategies that support their interpersonal relationships. Previous research has indicated that individuals who score high in the extraversion measure use active coping strategies and positive reappraisal. For this reason, individuals who are high in extraversion have the ability to cope flexibly, as they are able to adapt their coping responses according to each situation (Fickova 2009; Marnie 2008).

Likewise, agreeableness was found to be positively related to problem-focused coping and negatively related to emotion-focused coping, which parallels studies that suggest the importance of agreeableness for adaptive coping (Fickova 2009; Leandro and Castillo 2010). One explanation for this can be viewed in the notion than individuals who score high in the agreeableness measure have a preference for altruism, self-satisfaction, trust, and usefulness. These individuals, thus, use positive reappraisal strategies, social support, and careful planning to a much greater extent that maladaptive emotion-focused coping strategies such as self-blaming and avoidance (Fickova 2009; Leandro and Castillo 2010). This leads to the conclusion that agreeableness is a positive trait that is specifically helpful during times of crises. This is because individuals high in agreeableness usually avoid conflict and do not take advantage of others (Costa and McCrae 1992), which are considered key characteristics for dealing more effectively with stress caused by a crisis (Mirhaghi and Sarabian 2016).

Conscientiousness was also found to be positively related to problem-focused coping and negatively related to emotion-focused coping, which aligns with existing studies that note the importance of conscientiousness for adaptive coping (Karimzade and Besharat 2011; Leandro and Castillo 2010; Roesch et al. 2006). Such findings can be explained by the notion that individuals who score high in the conscientiousness measure are usually careful planners and rational decision, especially when being faced with a stressor (Chartrand et al.,1993; Hooker et al. 1994; Vollrath et al. 1994). These individuals, thus, tend to use active problem-focused coping strategies and avoid maladaptive emotion-focused coping strategies (McCrae and Costa Jr 1986; Ramírez-Maestre et al. 2004; Leandro and Castillo 2010).

At the other end of the spectrum, a person who is high in neuroticism has a tendency to easily experience emotional imbalances. In contrast to the findings above, Neuroticism was found to be negatively related to problem-focused coping and positively related to emotion-focused coping, which is consistent with prior research demonstrating the positive correlation between neuroticism and maladaptive coping strategies (Carlo et al. 2012; Chwaszcz et al. 2018; Roesch et al. 2006; Zainah et al. 2019). One explanation for this can be found in the notion that individuals who are high in Neuroticism are more susceptible to psychological distress and irrational thoughts and are less able to control their impulses (Costa and McCrae 1992). Therefore, many researchers have found that Neuroticism is closely related to maladaptive and passive coping strategies such as self-blame, fantasizing and avoidance (Hengartner et al. 2017; Eksi 2010; Wang and Miao 2009).

Social Support and Coping Styles

The study results indicate that social support positively correlated with problem-focused coping and negatively correlated with emotion focused-coping, consistent with prior studies that highlight the importance of perceived social support for adaptive coping (Agbaria 2019; Agbaria and Bdier 2019; Agbaria and Natur 2018; Umberson and Karas Montez 2010; Wang et al. 2014). This can be explained by the notion that social support is effective in enhancing one’s well-being because it acts as a coping assistant (O’Brien and DeLongis 1996; Thoits 1986).

Perceptions of the availability of support and perceptions of support attempts from close ones influences the use of specific coping strategies as well as the effectiveness of coping strategies employed (Carpenter and Scott 1992). Social relationships influence people’s ways of coping in a number of ways. One way, for instance, is through the use of social referencing (Bandura 1986). That is, people turn to others for a sense of what is considered to be appropriate coping in a given situation. Social relationships also influence coping through providing information about the likely efficacy of particular coping strategies (Carpenter and Scott 1992).

Limitations

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of the following limitations. The sample was not recruited using a randomized subset of the larger population in order to understand features of one unique group, but future research may consider recruiting a more diverse sample to permit direct comparisons across racial and other religious groups a means to increase the generalizability of the current findings. In addition, the data was comprised only of self-report questionnaires, which may be subject to reporting bias. This may be especially high among college students who may be more likely to either conform to or rebel against social norms. Thus, further studies may consider additional tools of measurement (e.g., behavioral observations). Finally, there is need for future research to examine the relationships between coping with stress, the Big Five personality traits, and social support by testing a wider variety of moderating and mediating effects.

Conclusions

This study is the first to investigate the relationship between coping with stress at the beginning of the Coronavirus outbreak, the Big Five personality traits, and social support among a unique population of Israeli-Palestinian college students. The aim of the study was to examine how personality traits and social support may increase one’s adaptive coping. The results suggest that positive social support increases one’s ability to cope actively, adaptively, and efficiently. In addition, the results demonstrate that individuals high in openness, extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness tend to use active problem-focused coping while individuals high in neuroticism tend to use maladaptive emotion-focused coping. The present research provides valuable insight into coping with stress in a manner that may increase early identification and intervention efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

Agbaria, Q. (2013). Depression among Arab students in Israel: the contribution of religiosity, happiness, social support and self-control. Sociology Study, 3(10), 721–738.

Agbaria, Q. (2014). Religiosity, social support, self-control and happiness as moderating factors of physical violence among Arab adolescents in Israel. Creative Education, 5(2), 75–85.

Agbaria, Q. (2019). Predictors of personal and social adjustment among Israeli-Palestinian teenagers. Child Indicators Research, 96, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.2.195.

Agbaria, Q., & Bdier, D. (2019). The role of self-control, social support and (positive and negative affects) in reducing test anxiety among Arab teenagers in Israel. Child Indicators Research, 13, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09669-9.

Agbaria, Q., & Natur, N. (2018). The relationship between violence in the family and adolescents aggression: The mediator role of self-control, social support, religiosity, and well-being. Children and Youth Services Review, 91, 447–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.06.016.

Agbaria, Q., Ronen, T., & Hamama, L. (2012). The link between developmental components (age and gender), need to belong and resources of self-control and feelings of happiness, and frequency of symptoms among Arab adolescents in Israel. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(10), 2018–2027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.03.009.

Agbaria, Q., Mahamid, F., & ZiyaBerte, D. (2017). Social support, self-control, religiousness and engagement in high risk-behaviors among adolescents. The International Journal of Indian Psychology, 4, 13–33.

Al Hajj, M. (1996). Identity and orientation among Arabs in Israel: a state of double periphery. In R. Gibson & D. Hacker (Eds.), The Jewish-Arabic Divide in Israel, a reader. Israel Institute for Democracy: Jerusalem (In Hebrew).

Altena, E., Baglioni, C., Espie, C. A., Ellis, J., Gavriloff, D., Holzinger, B., et al. (2020). Dealing with sleep problems during home confinement due to the COVID-19 outbreak: Practical recommendations from a task force of the European CBT-I Academy. Journal of Sleep Research, e13052. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13052.

Amirkhan, J. H., Risinger, R. T., & Swickert, R. J. (1995). Extraversion: a “hidden” personality factor in coping? Journal of Personality, 63(2), 189–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00807.x.

Austenfeld, J. L., & Stanton, A. L. (2004). Coping through emotional approach: a new look at emotion, coping, and health-related outcomes. Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1335–1364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00299.x.

Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 4(3), 359–373. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359.

Boyes, M. E., & French, D. J. (2010). Neuroticism, stress, and coping in the context of an anagram-solving task. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(5), 380–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.04.001.

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395, 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8.

Buheji, M., & Ahmed, D. (2020). Foresight of Coronavirus (COVID-19) opportunities for a better world. American Journal of Economics, 10(2), 97–108.

Byrd, D. R., & McKinney, K. J. (2012). Individual, interpersonal, and institutional level factors associated with the mental health of college students. Journal of American College Health, 60(3), 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2011.584334.

Carlo, G., Mestre, M. V., McGinley, M. M., Samper, P., Tur, A., & Sandman, D. (2012). The interplay of emotional instability, empathy, and coping on prosocial and aggressive behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(5), 675–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.05.022.

Carpenter, B. N., & Scott, S. M. (1992). Interpersonal aspects of coping. In B. N. Carpenter (Ed.), Personal coping: Theory, research, and application (pp. 93–110). New York: Praeger.

Carver, C. S., & Connor-Smith, J. (2010). Personality and coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 679–704. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100352.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267.

Cellini, N., Canale, N., Mioni, G., & Costa, S. (2020). Changes in sleep pattern, sense of time and digital media use during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. Journal of Sleep Research, e13074. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13074.

Chai, M. S., & Low, C. S. (2015). Personality, coping and stress among university students. American Journal of Applied Psychology, 4(3-1), 33–38. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajap.s.2015040301.16.

Chandra, C. M., Szwedo, D. E., Allen, J. P., Narr, R. K., & Tan, J. S. (2020). Interactions between anxiety subtypes, personality characteristics, and emotional regulation skills as predictors of future work outcomes. Journal of Adolescence, 80, 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.02.011.

Chartrand, J. M., Rose, M. L., Elliott, T. R., Marmarosh, C., & Caldwell, S. (1993). Peeling back the onion: personality, problem solving, and career decision-making style correlates of career indecision. Journal of Career Assessment, 1(1), 66–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/106907279300100107.

Chwaszcz, J., Lelonek-Kuleta, B., Wiechetek, M., Niewiadomska, I., & Palacz-Chrisidis, A. (2018). Personality traits, strategies for coping with stress and the level of internet addiction—a study of polish secondary-school students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(5), 987. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050987.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310.

Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J. K., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 87–127. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.87.

Connor-Smith, J. K., & Flachsbart, C. (2007). Relations between personality and coping: a meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(6), 1080–1107. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1080.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: the NEO personality inventory. Psychological Assessment, 4(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.5.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (2008). The revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R). Sage Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849200479.n9.

Costa, P. T., Somerfield, M., & McCrae, R. (1996). Personality and coping: a reconceptualization. In M. Zeidner & N. S. Endler (Eds.), Handbook of coping: Theory, research, applications (p. 44–61). Wiley.

Cutrona, C. E. (1996). Social support in couples: marriage as a resource in times of stress, 13. Sage Publications.

Dakof, G. A., & Taylor, S. E. (1990). Victims’ perceptions of social support: what is helpful from whom? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.1.80.

David, J. P., & Suls, J. (1999). Coping efforts in daily life: role of big five traits and problems appraisals. Journal of Personality, 67, 265–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00056.

DeLongis, A., & Holtzman, S. (2005). Coping in context: the role of stress, social support, and personality in coping. Journal of Personality, 73(6), 1633–1656. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00361.x.

Digman, J. M. (1989). Five robust trait dimensions: development, stability, and utility. Journal of Personality, 57, 195–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1989.tb00480.x.

Digman, J. M., & Inouye, J. (1986). Further specification of the five robust factors of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 116–123. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.50.1.116.

Drazen, J. M., Kanapathipillai, R., Campion, E. W., Rubin, E. J., Hammer, S. M., Morrissey, S., & Baden, L. R. (2014). Ebola and quarantine, 2029–2030. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe1413139.

Eksi, H. (2010). Personality and coping among Turkish college students: a canonical correlation analysis. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 10(4), 2159–2176.

Ericson, T. (1962). Pion capture as a tool for shell model studies. Physics Letters, 2, 278–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9163(62)90037-9.

Ezeakabekwe, S. U., & Nwankwo, E. A. (2020). Correlate of personality traits, self-efficacy and work copping among police personnel: the need for psychotherapy services for police personnel in Awka Metropolis. International Journal For Psychotherapy in Africa, 4(1).

Fickova, E. (2009). Reactive and proactive coping with stress in relation to personality dimensions in adolescents. Studia Psychologica, 51(2–3), 149–160.

Finset, A., Steine, S., Haugli, L., Steen, E., & Laerum, E. (2002). The brief approach/avoidance coping questionnaire: development and validation. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 7(1), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500120101577.

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21(3), 219–239. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136617.

Fu, W., Wang, C., Zou, L., Guo, Y., Lu, Z., Yan, S., & Mao, J. (2020). Psychological health, sleep quality, and coping styles to stress facing the COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Translational Psychiatry, 10, 225. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-00913-3.

Gunthert, K. C., Cohen, L. H., & Armeli, S. (1999). The role of neuroticism in daily stress and coping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(5), 1087–1100. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.5.1087.

Hengartner, M. P., van der Linden, D., Bohleber, L., & von Wyl, A. (2017). Big five personality traits and the general factor of personality as moderators of stress and coping reactions following an emergency alarm on a Swiss University Campus. Stress and Health, 33(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2671.

Hiremath, P., Kowshik, C. S., Manjunath, M., & Shettar, M. (2020). COVID 19: Impact of lock-down on mental health and tips to overcome, 51, 102088. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 102088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102088.

Holahan, C. J., Moos, R. H., Holahan, C. K., Brennan, P. L., & Schutte, K. K. (2005). Stress generation, avoidance coping, and depressive symptoms: a 10-year model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(4), 658–666. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.658.

Hooker, K., Frazier, L. D., & Monahan, D. J. (1994). Personality and coping among caregivers of spouses with dementia. Gerontologist, 34(3), 386–392. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/34.3.386.

Jeong, H., Yim, H. W., Song, Y. J., Ki, M., Min, J. A., Cho, J., & Chae, J. H. (2016). Mental health status of people isolated due to Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Epidemiology and Health, 38. https://doi.org/10.4178/epih.e2016048.

John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: history, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. Handbook of personality: Theory and research, 2(1999), 102–138.

Karimzade, A., & Besharat, M. A. (2011). An investigation of the relationship between personality dimensions and stress coping styles. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 797–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.155.

Khoury, J. “COVID-19 Testing in Israel’s Arab Community Drops, as Do Mass Events.” Haaretz.com, Haaretz, 6 Oct. 2020, www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-covid-19-testing-in-israel-s-arab-community-drops-as-do-mass-events-1.9212469.

Lazarus, R. S. (1966). Psychological stress and the coping process.

Lazarus, R. S. (1993). Coping theory and research: Past, present, and future. Fifty years of the Research and Theory of RS Lazarus: An Analysis of Historical and Perennial Issues, 366–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00944.x.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer Pub. Co..

Leandro, P. G., & Castillo, M. D. (2010). Coping with stress and its relationship with personality dimensions, anxiety, and depression. Journal of Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 1562–1573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.326.

Lee-Baggley, D., Preece, M., & DeLongis, A. (2005). Coping with interpersonal stress: role of Big Five traits. Journal of Personality, 73(5), 1141–1180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00345.x.

MacCann, C., Fogarty, G. J., Zeidner, M., & Roberts, R. D. (2011). Coping mediates the relationship between emotional intelligence (EI) and academic achievement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(1), 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.11.002.

Marnie, B. M. (2008). The role of personality following the September 11th terrorist attacks: Big Five Trait combinations and interactions in explaining distress and coping (unpublished doctoral dissertation in psychology and social behavior). University of California, U.S.

McCrae, R. R. (Ed.). (1992). The five-factor model: Issues and applications [special issue]. Journal of Personality, 60(2), 175–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00970.x.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa Jr., P. T. (1986). Personality, coping, and coping effectiveness in an adult sample. Journal of Personality, 54(2), 385–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1986.tb00401.x.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa Jr., P. T. (1987). Validation of a five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81.

Mervielde, I., Buyst, V., & De Fruyt, F. (1995). The validity of the Big-Five as a model for teachers’ ratings of individual differences among children aged 4–22 years. Personality and Individual Differences, 18, 525–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(94)00175-R.

Mirhaghi, M., & Sarabian, S. (2016). Relationship between perceived stress and personality traits in emergency medical personnel. Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health, 18(5), 265–271 http://jfmh.mums.ac.ir/article_7480.html.

Nes, L. S., & Segerstrom, S. C. (2006). Dispositional optimism and coping: a meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_3.

O’Brien, T. B., & DeLongis, A. (1996). The interactional context of problem-, emotion- and relationship-focused coping: the role of the Big Five personality factors. Journal of Personality, 64, 775–813. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00944.x.

Odeh, L. (2014). Personal growth of Arab mothers who are growing a child with and without intellectual disability. Haifa: Faculty of Education, University of Haifa.

Parkes, K. R. (1986). Coping in stressful episodes: the role of individual differences, environmental factors, and situational characteristics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1277–1292. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1277.

Penley, J. A., & Tomaka, J. (2002). Associations among the Big Five, emotional responses, and coping with acute stress. Personality and Individual Differences, 32(7), 1215–1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00087-3.

Ramírez-Maestre, C., Martínez, A. E. L., & Zarazaga, R. E. (2004). Personality characteristics as differential variables of the pain experience. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 27(2), 147–165. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBM.0000019849.21524.70.

Revenson, T. A. (1990). Social support processes among chronically ill elders: patient and provider perspectives. Communication, Health and the Elderly, 92–113.

Riley, K. E., & Park, C. L. (2014). Problem-focused coping vs. meaning-focused coping as mediators of the appraisal-adjustment relationship in chronic stressors. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 33(7), 587–611.

Roberts, B. W. (2017). A revised sociogenomic model of personality traits. Journal of Personality, 86(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12323.

Robertson, E., Hershenfield, K., Grace, S. L., & Stewart, D. E. (2004). The psychosocial effects of being quarantined following exposure to SARS: a qualitative study of Toronto health care workers. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 49(6), 403–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370404900612.

Roesch, S. C., Wee, C., & Vaughn, A. A. (2006). Relations between the Big Five personality traits and dispositional coping in Korean Americans: acculturation as a moderating factor. International Journal of Psychology, 41(02), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590544000112.

Rogowska, A. M., Kuśnierz, C., & Bokszczanin, A. (2020). Examining anxiety, life satisfaction, general health, stress and coping styles during COVID-19 pandemic in polish sample of university students. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 13, 797–811. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S266511.

Roth, S., & Cohen, L. J. (1986). Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. American Psychologist, 41(7), 813–819. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.7.813.

Samoha, S. (2004). Index of Arab-Jewish relations in Israel. Haifa: Rekhes (In Hebrew). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264875701.

Scher, S. J., & Osterman, N. M. (2002). Procrastination, conscientiousness, anxiety, and goals: exploring the measurement and correlates of procrastination among school-aged children. Psychology in the Schools, 39(4), 385–398. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10045.

Sheridan, Z., Boman, P., Mergler, A., Furlong, M. J., & Elmer, S. (2015). Examining well-being, anxiety, and self-deception in university students. Cogent Psychology, 2(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2014.993850.

Skinner, E. A., Edge, K., Altman, J., & Sherwood, H. (2003). Searching for the structure of coping: a review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 216. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216.

Smith, T. W., Pope, M. K., Rhodewalt, F., & Poulton, J. L. (1989). Optimism, neuroticism, coping, and symptom reports: an alternative interpretation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(4), 640–648. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.4.640.

Stoneman, Z., Gavidia-Payne, S., & Floyd, F. (2006). Marital adjustment in families of young children with disabilities: associations with daily hassles and problem-focused coping. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 111, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1352/0895-8017(2006)111[1:MAIFOY]2.0.CO;2.

Sue, D. W., & Sue, D. (2003). Counseling the culturally diverse: theory and practice (4th ed.). New York: Wiley.

Suls, J., Green, P., & Hillis, S. (1998). Emotional reactivity to everyday problems, affective inertia, and neuroticism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(2), 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167298242002.

Swider, B. W., & Zimmerman, R. D. (2010). Born to burnout: a meta-analytic path model of personality, job burnout, and work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76, 487–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.01.003.

Thoits, P. A. (1986). Social support as coping assistance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(4), 416–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.54.4.416.

Torales, J., O’Higgins, M., Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., & Ventriglio, A. (2020). The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020915212.

Umberson, D., & Karas Montez, J. (2010). Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(1_suppl), S54–S66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510383501.

van Berkel, H. K. (2009). The relationship between personality, coping styles and stress, anxiety and depression. https://canterbury.libguides.com/rights/theses.

Vollrath, M., & Torgersen, S. (2000). Personality types and coping. Personality and Individual Differences, 29(2), 367–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00199-3.

Vollrath, M., Banholzer, E., Caviezel, C., Fischli, C., & Jungo, D. (1994). Coping as a mediator or moderator of personality in mental health. Personality Psychology in Europe, 5, 262–273.

Vreeke, L., & Muris, P. (2012). Relations between behavioral inhibition, Big Five personality factors, and anxiety disorder symptoms in non-clinical and clinically anxious children. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 43(6), 884–894. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-012-0302-5.

Wang, W., & Miao, D. (2009). The relationships among coping styles, personality traits and mental health of Chinese medical students. Social Behavior and Personality, 37(2), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2009.37.2.163.

Wang, X., Cai, L., Qian, J., & Peng, J. (2014). Social support moderates stress effects on depression. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 8(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-8-41.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1992). On traits and temperament: general and specific factors of emotional experience and their relation to the five-factor model. Journal of Personality, 60, 441–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00980.x.

Watson, D., & Hubbard, B. (1996). Adaptational style and dispositional structure: Coping in the context of the five-factor model. Journal of Personality, 64(4), 737–774. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00943.x.

Zainah, M., Muhammad, N. A. A., & Nor, S. A. (2019). Adult personality and its relationship with stress level and coping mechanism among final year medical students. Medicine & Health, 14(2), 154–167. https://doi.org/10.17576/MH.2019.1402.14.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The manuscript has only been submitted to The International journal of mental health and addiction, it will not be submitted elsewhere while under consideration, and it has not been published elsewhere – either in similar form or verbatim. I am responsible for the reported research and all authors have participated in the concept and design; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting or revising of the manuscript, and I have reviewed/approved the manuscript. There are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (include name of committee + reference number) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Agbaria, Q., Mokh, A.A. Coping with Stress During the Coronavirus Outbreak: the Contribution of Big Five Personality Traits and Social Support. Int J Ment Health Addiction 20, 1854–1872 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00486-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00486-2