Abstract

With continued growth in online learning, motivation remains a key factor in persistence and achievement. Online mathematics students struggle with self-regulation and self-efficacy. As reported by Ryan and Deci (Self-determination theory: basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness, Guilford Press, 2017, https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-2004-22201), in their well-established self-determination theory, contended that satisfying the psychological needs of autonomy (involving self-regulation), competence (involving self-efficacy), and relatedness (involving a sense of belonging) creates a suitable environment for integrated extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to thrive. The purpose of this action research was to implement a self-determination theory-based online unit for mathematics students to improve their motivation levels. A convergent mixed methods action research design was employed to identify changes in the levels of autonomy, competence, and relatedness of the participants in an Algebra 2 course (n = 50) at a fully online school in the northeastern United States. Results from the motivation questionnaire and student interviews indicated a significant increase in competence and relatedness after completing the intervention. While no significant increase in autonomy was evident in the quantitative results, the qualitative findings showed some support for improved autonomy. Recommendations for online mathematics course design to support increased motivation are provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Motivation in online learning

Motivation in online learning has been linked to improved learning outcomes, achievement, persistence, and retention (Froiland et al., 2016; Hew, 2016; Hsu et al., 2019; Kim, 2015; Martin et al., 2018). Yet motivation has languished in online mathematics students as a result of self-regulatory and self-efficacious challenges (Durksen et al., 2017; Tang, 2021; Wilkie & Sullivan, 2018; Yantraprakorn et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2022).

Self-regulatory challenges can arise from an external locus of control and an isolated environment. A heightened focus on extrinsic rewards and punishments, in general, is likely to have a negative effect on autonomous regulation (Ryan & Deci, 2020). For example, Bourgeois and Boberg (2016) found that motivation decreased from Grades 3 to 8, caused by a focus on grades as an extrinsically motivating factor, removing autonomy from students. This lack of self-regulation may result in further decreased motivation due to an absence of direct instructor encouragement and social interaction (Sun & Rueda, 2012).

Self-efficacious challenges can arise from a lack of clear expectations, support, confidence, and interesting challenge (Durksen et al., 2017; Wilkie & Sullivan, 2018). Inappropriate goal setting and insufficient or unhelpful feedback can also result in reduced self-efficacy in online learners (Yantraprakorn et al., 2018).

Deci and Ryan’s (1985) self-determination theory effectively addresses the self-regulatory and self-efficacious challenges of motivation in online environments through the fulfillment of the three psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. For example, Hsu et al. (2019) found that self-determination theory can be efficaciously applied to the online environment to enhance self-regulated motivation in a study of seven online courses with 330 participants. Other researchers found that designing virtual learning based on self-determination theory improved motivation and learning among their 198 participants (Huang et al., 2019). Other studies have also found that motivation increases when implementing online content that facilitates the needs of self-determination theory (Jacobi, 2018; Martin et al., 2018; Proulx et al., 2017; Ryan & Deci, 2017).

The current study

The purpose of this action research was to create and implement a self-determination theory-based online unit for mathematics students to improve students’ motivation levels. This study aimed to identify specific online course design components that facilitated feelings of autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

Literature review

Definition of motivation

The underlying theme in definitions of motivation is the exploration of catalysts for action or behavior. Humans are driven to interact with their environment because of feelings of satisfaction that their “behavior has an exploratory, varying, experimental character and produces changes in the stimulus field” (White, 1959, p. 329). In general terms, motivation is “what moves people to action” (Ryan & Deci, 2017, p. 13) and “refers to those things that explain the direction, magnitude, and persistence of behaviors” (Keller, 2016, p. 4).

Types of motivation

Motivation in education has been defined by the basic underpinnings of extrinsic motivation, involving external punishments, rewards, and outcomes; and intrinsic motivation, involving internal interest, curiosity, and volition (Lambert, 2017; Lee & Martin, 2017; Leong et al., 2018; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Skinner (1953) asserted through his description of operant conditioning that external reinforcement, such as rewards, is the driving motivator behind behavioral change. Mechanistic theories of motivation arise from this approach, where the learner takes a passive role and acts based on physiological needs or environmental factors (Deci & Ryan, 1985). On the other hand, White (1959) contended that humans have an internal need to efficaciously interact with their environment. Organismic theories of motivation arise from this approach, where the learner takes an active role and willfully generates behavior (Deci & Ryan, 1985).

Self-determination theory

Self-determination theory (SDT) is a well-recognized, empirical, practical, and organismic theory of motivation (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2017). SDT is rooted in psychological needs’ fulfillment. Specifically, the satisfaction that comes from meeting the needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness is the underlying catalyst for motivation. Social factors can support or undermine the three needs (Ryan & Deci, 2017). In this theory, motivation varies in strength and orientation, as described by a continuum of motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2017, 2020).

Continuum of motivation

The continuum of motivation includes amotivation, controlled and autonomous extrinsic motivation, and intrinsic motivation (Gagne & Deci, 2005; Ryan & Deci, 2000, 2020). The positive effects of controlled extrinsic motivation may be temporal, while autonomous extrinsic and intrinsic motivation are best for the learner (Cho & Shen, 2013; Kapp, 2012; Ryan & Deci, 2000, 2020). The transition from controlled to autonomous extrinsic motivation can be facilitated by internal, environmental, and social factors that support the needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Gagne & Deci, 2005; Ryan & Deci, 2000, 2020).

Psychological needs

Autonomy

Autonomy represents a person’s self-regulation or volition (Ryan & Deci, 2017; Tamborini et al., 2010). A self-regulated person feels in control of and accepts his or her behavior (Ryan & Deci, 2020; Tang, 2024; Tang & Bao, 2022). While heteronomy, restrictions, and exclusively extrinsic reinforcement can undermine it, autonomy is fostered by intrinsically motivating tasks that provide choice, value, and interest (Ryan & Deci, 2020). Choice is best given with a sense of trust and empowerment and followed with positive informative feedback (Rayburn et al., 2018). Additional resources, especially in the area of vocabulary acquisition, can improve autonomy (Qian & Sun, 2019). These resources, along with frequent, constructive, and informational feedback may add to a supportive structure where the feeling of freedom is enhanced (Hartnett, 2015; Ryan & Deci, 2020). In sum, autonomy can be facilitated through choice, interest, empowerment, and non-controlling structure.

Competence

Ryan and Deci’s (2017) definition of competence is based on White’s (1959) concept of effectance motivation. In essence, people are viewed as active players in their environment and seek effective interaction with it, resulting in internal satisfaction (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2017; White, 1959). Furthermore, people desire an appropriate challenge (Tamborini et al., 2010). Competence involves both optimal challenges and the perception of effectively completing those challenges (Proulx et al., 2017). Competence may be undermined if the challenge level is too easy (Huang et al., 2019) or too difficult (Hartnett, 2015) and if feedback pressures a person to act in a particular way (Ryan & Deci, 2020). Competence and autonomy are strongly dependent on one another, and so supporting autonomy also supports competence (Durksen et al., 2016). In particular, including the autonomous support of structure is imperative in improving competence (Ryan & Deci, 2020).

Strategies that improve competence fall under the umbrella of scaffolding. According to Vygotsky (1978), there is a zone between what students can do individually and what they are able to master with the help of others, called the zone of proximal development. Scaffolding involves helping the learner focus on tasks he or she is able to complete by limiting information or activities that are initially beyond his or her capability (Kapp, 2012). Personalization based on the prior knowledge of the learner, positive informative feedback, and an appropriate level of challenge are effective components of this process (Chen, 2014; Cho & Shen, 2013; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Strongly guided instruction, such as worked out examples or worksheets, aids in reducing cognitive load and fosters competence (Kirchener et al., 2006). In sum, utilizing a supportive structure with scaffolding, guided instruction, informative feedback, and optimally challenging enrichment likely foster the perception of competence.

Relatedness

Relatedness is the basic need for humans to feel genuinely connected to and accepted by others (Ryan & Deci, 2017). People often attempt to secure their acceptance by identifying others’ expectations and actions (Ryan & Deci, 2017). A person may integrate others’ values, leading to internalized extrinsic motivation, or view them as extrinsic controls, leading to controlled extrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2017). For the need of relatedness to thrive internally, a person must perceive unqualified social attachment or belongingness (Proulx et al., 2017). Forums may provide a means of connecting students and personalizing the experience (Tang et al., 2018). Yet disagreements or conflicts among group members, isolated environments, large courses sizes, or feelings of rejection can undermine relatedness (Durksen et al., 2016; Hartnett, 2015; Martin et al., 2018; Ryan & Deci, 2017). In sum, relatedness can be supported by a positive, open, and trusting environment with collaboration and clear expectations (Bourgeois & Boberg, 2016; Huang et al., 2019).

Basic psychological needs mini-theory

Through continued studies and research, Ryan and Deci (2017) formed the following six mini-theories to describe different aspects of motivation in self-determination theory: (a) cognitive evaluation theory delineates how intrinsic motivation is affected by social environments, (b) organismic integration theory provides support for the continuum bringing controlled extrinsic motivation to autonomous extrinsic motivation, (c) causality orientations theory details differences in personality and how they are affected by the social environment, (d) basic psychological needs theory reveals the ways that health and well-being are affected by the level of need satisfaction, (e) goal contents theory considers people’s intrinsic and extrinsic goals, and (f) relationships motivation theory identifies how relatedness and autonomy are connected through interpersonal relationships.

Among the mini-theories, the basic psychological needs mini-theory has special significance in this study. In this theory, Ryan and Deci (2017) moved beyond motivation into a broader interpretation of human well-being. Well-being is understood “in terms of thriving or being fully functioning rather than merely by the presence of positive and absence of negative feelings” (Ryan & Deci, 2017, p. 241). This thriving is grounded in efficaciously undertaking worthwhile endeavors (Ryan & Deci, 2017). A person who is appropriately motivated through the satisfaction of autonomy, competence, and relatedness will experience wellness and vitality. Conversely, the frustration of these three needs causes a person’s ill-being (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

Course design

The basic structure of the lessons in the Algebra 2 course at Peacock Cyber School generally follows Gagne’s nine events of instruction. The layout of the lessons in the intervention unit continued to follow this format, with modifications made based on the implementation strategies of self-determination theory.

In Gagne’s nine events of instruction, external events of instruction support the internal processes that cause learning (Gagne et al., 1992). The nine external events include: (a) gaining attention, (b) informing learners of objectives, (c) stimulating recall of prior knowledge, (d) presenting the content, (e) providing learning guidance, (f) eliciting performance, (g) providing feedback about correctness, (h) assessing performance, and (i) enhancing retention and transfer (Gagne, 1985; Gagne et al., 1992).

Unlike broader models of instructional design, Gagne’s nine events of instruction can provide an effective layout for a specific lesson. For example, Polat and Oz (2017) used Gagne’s nine events of instruction as the basis for creating a specific lesson plan for 23 eighth grade students in informational technology because of its usefulness in facilitating learning. In a comparative quantitative study of Gagne’s nine events of instruction used in a postgraduate armed forces institute, its implementation as a framework for lessons improved student satisfaction, performance, and retention (Ullah et al., 2015). Similarly, Jaiswal’s (2019) use of Gagne’s nine events as a student-centered approach among 26 English language learners enhanced retention and transfer. In other studies, this model has improved meaningful knowledge acquisition and retention (Davies et al., 2018) and has supported organization, efficiency, and student success in online course design (Jeffery & Ahmad, 2018).

Implications for the current study

To summarize, self-determination theory is a well-established theory of motivation that attributes the level and type of motivation to the extent to which the internal needs of autonomy, competence and relatedness are satisfied (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Proulx et al., 2017; Ryan & Deci, 2017; Tamborini et al., 2010). These psychological needs have specific characteristics that can be designed for in online lessons using distinct strategies (Durksen et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2019; Rayburn et al., 2018; Ryan & Deci, 2000, 2020). Furthermore, motivation is defined on a continuum with varying degrees of controlled and autonomous extrinsic motivation and intrinsic motivation (Gagne & Deci, 2005; Ryan & Deci, 2000, 2020). The fulfillment of autonomy, competence, and relatedness is the foundation for internalized extrinsic and intrinsic motivation in self-determination theory (Gagne & Deci, 2005; Ryan & Deci, 2000, 2020).

Gagne’s nine events of instruction provide a solid structure for lesson design (Jaiswal, 2019; Jeffery & Ahmad, 2018; Polat & Oz, 2017; Ullah et al., 2015). This structure forms the basic template for the lessons in the Algebra 2 course. Designing intervention lessons containing this structure, with the addition of supports for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, as described by self-determination theory, is likely to improve the intrinsic and autonomous extrinsic motivation of online mathematics students.

The main research question for this study was: How does the implementation of a self-determination theory-based unit on factoring polynomials in an online mathematics course affect students’ feelings of autonomy, competence, and relatedness?

Method

Action research has the purposes of connecting theory with action, improving an aspect of the researcher’s sphere of influence, improving a problem for the local participants, and applying the intended benefit to all participants (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Mertler, 2017; Sagor, 2000). These purposes align with the goals of the current study. A lack of motivation among students to complete mathematics lessons was identified in the local context and this study was conducted with the goal of improving that problem for all participants utilizing self-determination theory. This action research study employed a convergent mixed methods design (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2017; Tang et al., 2020, 2021) to provide a holistic understanding of the effects of the self-determination theory-based unit on students’ autonomy, competence, and relatedness levels.

Setting

This study took place at a fully online public school located in the northeast region of the United States for students in Grades 6–12. Students worked remotely and asynchronously, with optional synchronous class meeting times. The first author is employed at this school as the mathematics content developer and created the intervention unit used in the Algebra 2 course. The Algebra 2 course was chosen as a purposive sample so that the same intervention with the same teachers could be given to all of the participants (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Tang et al., 2020, 2021). This course is prototypical of the mathematics content at the school and tends to have the highest enrollment among the math courses.

Participants

Students enrolled in the Algebra 2 course ranged from Grade 7 to Grade 12 and were split into three sections: career, college-prep, and honors, based on their academic histories and teacher recommendations. An Institutional Review Board approval was granted before the participants were recruited. Informed assent and parental consent forms were distributed to approximately 200 students enrolled in the Algebra 2 course at the time of the study, of which 54 consented to participate in the study, and 50 fully completed the study. Of the students that agreed to participate, 12 were enrolled in the career section, 24 in college-prep, and 18 in honors. Participants from each section were asked to take part in the interviews, of which six agreed to participate. Table 1 shows demographic information and pseudonyms for these participants.

Procedures

The procedures for this research were organized into four phases. The first phase lasted approximately 2 weeks and consisted of identifying the participant list based on the Algebra 2 students and parents that provided informed assent and consent, having each participant complete the motivation and content knowledge pretests for the study, and unlocking the intervention unit. The second phase was the intervention itself and took about 3 to 4 weeks. In this phase, the participants completed and submitted approximately two lessons, a quiz, and three posts to a discussion forum during each week. Students progressed through the coursework independently, so the timeframe and start dates differed. The third phase, taking about 6 to 8 weeks, involved data collection through the content knowledge and motivation posttests and six semi-structured interviews. The fourth phase consisted of the analysis of the collected data and took approximately 8 to 12 weeks.

Intervention

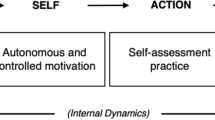

An online mathematics unit based on (Deci & Ryan, 1985) self-determination theory replaced an existing unit in the Algebra 2 course. A summary of the design components in the intervention unit, based on the implementation strategies of autonomy, competence, and relatedness described in Sect. “Psychological needs”, is provided in Fig. 1.

Autonomy components

Purposeful multipage structure within the lessons, additional vocabulary resources with built-in optional features, optional self-check buttons, optional remediation buttons, and optional guided enrichment questions were designed to support autonomy.

The intervention lessons had a multipage structure with the following five distinct pages: the opening page, the introductory information page, two lesson example pages, and the summary with practice problems page. On the vocabulary page, a video explanation of the words with visual connections was added to the list of vocabulary words already provided. Students had the choice to read the vocabulary words, watch the video, or both, as shown in Fig. 2. These features were meant to provide non-controlling structure and enhance autonomy for the learner (Qian & Sun, 2019).

Choice was incorporated through optional check buttons, optional remediation buttons, and optional guided enrichment questions. Check buttons appeared after each check for understanding question within the lessons. Upon pressing the check button, students received immediate informative and correctness feedback. Optional remediation was provided in the form of support videos or examples within buttons on the page, as shown in Fig. 3. Enrichment questions added extra challenge for learners who felt they were ready for more difficult problems associated with the content. The enrichment questions did not negatively affect students’ overall score if skipped. These optional features were meant to reduce pressure and increase self-regulation by means of authentic student choice (Martin et al., 2018).

Competence components

Prior knowledge checks, strongly guided instruction with practice, self-check buttons, a grade for the lesson, and optional guided enrichment questions were designed to support competence.

The prior knowledge section on the first page of the lessons included a description of the prior knowledge students should have before beginning the lesson, guided instruction, and a check for understanding, as shown in Fig. 4. If students pressed the check button, correctness and informative feedback was provided and they could attempt the question again.

Conceptual scaffolding was built into each example in the lesson to further support competence (Ak, 2016). Each example was separated onto its own page with strongly guided instruction. At the end of the example, a check for understanding question displayed a similar problem with the same procedures, as shown in Fig. 5. The guided instruction with step-by-step processes and worked out examples was meant to aid in conceptual scaffolding and in reducing cognitive load (Kirchener et al., 2006).

The check buttons and enrichment were designed to support both autonomy and competence. Providing correctness and informative feedback can facilitate feelings of self-efficacy (Cho & Shen, 2013). The enrichment questions were meant to offer optimal challenge for students while minimizing feelings of pressure, stress, and incompetence (Martin et al., 2018).

Once each lesson was completed and submitted by the student, the student received a grade for the lesson based on the correctness of their final answers. The grade reflected the growth in the student’s learning so that he or she may internalize and place value on the grade in association with self-efficacy.

Relatedness components

Forums and clear communication parameters for interaction were designed to support relatedness (Hew, 2016; Milman, 2017; Tang et al., 2018). Students were instructed to use positive and friendly communication and to post three quality discussion posts throughout each of the 3 weeks of the unit (Thompson et al., 2019). Tips for working in the lessons of the week, questions about how to complete a specific section of the lessons, and responses to a question providing informative feedback for another student were encouraged (Thompson et al., 2019; Wang, 2019). An assessment rubric was provided to clearly depict varying levels of responses (Thompson et al., 2019).

Data collection and analysis

Motivation questionnaire

The Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale (BPNSFS) is a questionnaire that has been established to align with the basic psychological needs mini-theory within self-determination theory (Chen et al., 2015; Cordeiro et al., 2015; Haerens et al., 2015). The questionnaire has six subscales: autonomy satisfaction and frustration, competence satisfaction and frustration, and relatedness satisfaction and frustration. It consists of 24 items, four for each of the six subscales, using a 5-point Likert scale. Minor wording adjustments were made to the original BPNSFS to fit the setting of this study. For example, items include “the activities in the unit feel like a chain of obligations” and “I have the impression that teachers or students I interact with dislike me.” This questionnaire was given as a pretest and posttest to every participant in the study. Cronbach’s alpha value for the pretest was .88, which is an acceptable level of reliability (Taber, 2018).

Descriptive and inferential statistics were used for the motivation questionnaire and inductive analysis was conducted for the student interviews. Descriptive statistics included means and standard deviations based on composite scores of the three subscales: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. A Shapiro–Wilk normality test was performed to examine whether the assumption of normal distribution was net. Results from the Shapiro–Wilk test suggested that competence deviated from normality (p < .001) while autonomy (p = .029) and relatedness (p = .174) had normal distribution. Thus, inferential statistics included a Wilcoxon signed-rank test rather than a t-test.

Student interviews

The interviews followed a semi-structured format with preplanned and follow-up questions (Mertler, 2017; Myers & Newman, 2007). Of the participants that were purposively selected, three from the college-prep section and three from the honors sections agreed to the interviews. The demographic information for these six interviewees was provided in Table 1. Since the interviews probed into how the intervention affected perceptions of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, interpreting the responses in conjunction with the motivation questionnaire subscales provided a triangulation of the data.

The interviews were conducted over the computer, audio recorded, and then transcribed with the final transcription containing 10,903 words. Inductive analysis was utilized to identify emerging themes based on the participants’ perceptions (Mertler, 2017; Strauss, 1987). Specifically, eclectic coding was used to identify initial codes based on participant responses, including in vivo terms (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Thomas, 2006). Eclectic coding “employs a select and compatible combination of two or more first cycle coding methods” in order to serve as “an initial, exploratory technique with qualitative data” (Saldana, 2021, p. 223). This process continued with refining the codes, applying classifications, and identifying categories to ascertain emergent themes (Strauss, 1987; Wiebe et al., 2010). Figure 6 shows a sample of this process. The inductive analysis process resulted in 376 codes, 4 classifications, 19 categories, 3 themes, and 3 assertions.

Peer debriefing and member checking were utilized to improve the accuracy of the analysis (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Mertler, 2017). With peer debriefing, the dissertation advisor and committee critiqued and gave feedback for improvements based on the research design, methods of data collection and analysis, findings, and other relevant parts of the study. Member checking included emailing the interviewees with their interview transcript and a summary of the qualitative findings for review and input. No recommendations for changes were given by the participants.

Results

Motivation questionnaire

A mean composite score was calculated for autonomy, competence, and relatedness for each participant (n = 50) using the satisfaction score and reversed frustration score (Chen et al., 2015). The means and standard deviations increased slightly between the pretest and posttest, with variance ranging from .51 to.79, as shown in Table 2.

A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted to determine whether participants increased in autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Using the standard alpha value of .05, The results indicated that there was no significant difference in autonomy from the pretest (Mdn = 3.25) to posttest (Mdn = 3.31, W = 423.50, p = .092). A significant difference was demonstrated in competence from the pretest (Mdn = 3.63) to posttest (Mdn = 4.00, W = 233.00, p = .001) and in relatedness from the pretest (Mdn = 3.63) to posttest (Mdn = 3.69, W = 368.00, p = .038). Overall, these results suggest that the participants increased in competence and relatedness from the pretest to posttest, while no statistically significant change was indicated for autonomy.

Student interviews

Table 3 provides a summary of the qualitative findings from the interviews.

Theme 1

Participants found the lesson structure supportive of their learning and not overwhelming. This theme germinated from ten categories involving the lesson structure, chunking, scaffolding, confidence with prior knowledge, useful prior knowledge, challenge questions, motivated by options, skipping optional material, resources, and expectations. Participants consistently conveyed that these elements helped them progress through the content effectively, increased their confidence, and reduced levels of stress in the lessons. In general, the statements of the participants aligned with prior research about autonomy and competence, which led to the following assertion: an all-in-one lesson structure including prior knowledge, optional help and challenge, and content chunking elements supported participants’ autonomy and competence, ultimately improving their motivation.

Lesson structure, chunking, and scaffolding

Lessons were structured to include the arrangement of activities over multiple pages with similar content chunked and scaffolded on each page. A lesson included both the presentation of information and graded practice. Multiple participants expressed that this structure was supportive of their learning:

- Finley::

-

[The multipage structure] felt nice. It made the whole transition from lessons into assignments in different parts of the lesson, and made it feel like it flowed a bit better rather than just like a big page of information and then a lone quiz on it.

- Devin::

-

I like [the multipage structure] because then it was kind of like here's like the lesson and learning it and then kind of enforcing it all in one, but it's like still sectioned, so you could go back if you needed to, like, look at it while still being in the lesson. And I found it useful.

Spreading the content over multiple pages helped to limit the information around a learner’s zone of proximal development (Vygotsky, 1978). The content chunking aided in guiding students through that zone and into new learning.

Prior knowledge

Students expressed the prior knowledge sections provided useful information and increased their confidence. For example, Cameron and Ava described the feelings of preparedness that resulted from completing the prior knowledge. Finley’s phrase “I wasn’t just like plunging into new stuff” seems to indicate an increased level of confidence or assurance from completing the prior knowledge before the lesson content.

- Cameron::

-

OK, I'm glad [the prior knowledge section] was there so I can like make sure I know this before I go into the lesson because a lot of the stuff I forgot. So they were really helpful and I felt a little more confident going into the lesson.

- Ava::

-

I liked completing [the prior knowledge sections] because it gave me confidence that I knew what I was doing so that I could then complete the lesson.

- Finley::

-

I wasn't just like plunging into new stuff without making sure I remembered the older topics.

Optional help and challenge items

The optional help and challenge questions designed for the intervention were used as a part of the scaffolding process, designed to support competence and autonomy. Participants expressed feeling less pressure, valuing the use of the options, and feeling helped by them:

- Blake::

-

I found [the options] useful in how we got different ways that we can learn the vocabulary, which was nice…[The optional enrichment] didn't make me feel pressured, which I like, I didn't feel pressured at all. So if I felt like doing the challenge question, I could, and if I didn't, I didn't have to.

- Finley::

-

I feel that [the options] just helped me to not feel so like nervous.

The scaffolding and supports for the optional enrichment questions may have benefitted participants’ in extending their learning and thought processes, as describe by Cameron:

- Cameron::

-

And [the challenge question] was like kind of challenging but good because like since it was like a longer thing…so I could see what's happening in the equation better. And I did something wrong the first time, but when I actually like looked closer, it's like, oh, I missed this. And then it was like helpful.

Participants described the perception that the challenge questions revealed deeper content for them in a digestible way, cultivating the theme that the lesson structure was supportive of their learning and not overwhelming.

Theme 2

This theme exposed the function of the feedback features within the lessons as they related to participants’ confidence and learning. The five categories involved feelings of stress, correctness feedback, informative feedback, appropriate content level, and the grade increasing motivation. Although some participants felt initial stress about the lessons, the correctness and informative feedback helped reduce this stress and foster the perception of competence. The perception of competence was further supported by the appropriate level of challenge within the lessons. Additionally, although somewhat controversial in research, the grade for the lesson did not seem to dampen participants’ motivation. Instead, it produced controlled extrinsic motivation for some while others found value and autonomous extrinsic motivation with the grade. This theme led to the assertion that correctness and informative feedback, provided with an appropriate level of challenge, may have fostered competence and autonomy, thereby increasing motivation.

Correctness feedback

Participants expressed that the ability to check their answers for correctness increased their confidence, thereby fostering competence. This category has the most codes associated with it compared to any other category. The underlying idea of this category (i.e., the checks increased confidence by providing solid assurance of the answers selected) was pinpointed in Finley’s statement: “I just felt like I could, you know, check and make sure rather than just hoping that it was right.” Finley had assurance in the answers selected, “rather than just hoping.” Other participants echoed this sentiment in their descriptions of increased confidence through the check buttons:

- Cameron::

-

I think I used [the check buttons] after every answer just to check that I was doing my work right and, you know, just to prove that I was actually learning…So, yeah, I did feel more confident as I was going through the lesson.

- Ava::

-

I think the check buttons… I think those helped my confidence the most.

The checks gave assurance that the participants were “actually learning,” improving their sense of competence.

Informative feedback

In addition to receiving correctness feedback, participants could also receive information about common mistakes and procedures needed to complete the problem, supporting both autonomy and competence. Cameron described using the feedback to find and learn from a mistake.

- Cameron::

-

I think [the check buttons are] really helpful with, like I said, just like reviewing and if I got it wrong and then it like provided feedback, I can just see where I went wrong… since there’s like feedback, then I can see, oh, yeah, I did that one wrong.

In a similar instance, Eddie explained that the process of using the check buttons allowed him to identify his mistake.

- Eddie::

-

Especially when you have multiple tries that even if you would mess up the first time, you could go back and look at your mistakes. I think it definitely made me feel more confident on my ability to learn the lesson.

In these examples, participants’ perceptions of competence were supported through informative feedback.

Appropriate content level

Based on participant responses, the difficulty level was reasonable, which may have provided a felicitous environment for competence. Intrinsically motivating optimally challenging environments “should be novel and surprising, but not completely incomprehensible. In general, an optimally complex environment will be one where the learner knows enough to have expectations about what will happen, but where these expectations are sometimes unmet” (Malone, 1981, p. 362). For example, the lesson content and check for understanding questions with feedback informed participants’ expectations for the questions. However, these expectations were sometimes beyond them, prompting the use of the check buttons with informative feedback to guide their learning processes.

Grade increased motivation

Participants received a grade for their performance on the lesson based on their final answers after using the check buttons. Based on the responses, it seems the grade supported and enhanced the motivation of the participants to complete the lessons. For example, Blake explained that the external motivator of the grade was enough to get her to complete the lessons.

- Blake::

-

[The grade] made me feel more motivated to do the lessons because sometimes on like Mondays when I'm trying to get through the lessons, I like really didn't want to do them, but I knew since it was graded, it gave me more motivation to do those.

Eddie’s sentiments also reflected the importance of earning points: “I didn't mind [the grade]. I think it gave me, just more of an opportunity to get more grade, like more points…I didn't mind having points for going through some practice questions.” He explained that the grade did not have a negative effect on his motivation and that he enjoyed earning more points because of the lesson.

In contrast, some participants seemed to internalize and place value on the purpose of the grade. For example, Finley expressed feeling like the grade encouraged her to work through the lesson step-by-step and supported the development of her learning.

- Finley::

-

[The grade] just made it feel more like I was steadily working through something than just doing nothing and trying to take in information and then using all that information at once… It helped the lesson to feel a bit more like I was doing something that was worthwhile and helped to kind of like know what parts of the lesson I really needed to go over.

The grade helped guide her learning and direct her to areas that she needed to review. Cameron described feeling that the grade helped ensure understanding, which was “gratifying.”

- Cameron::

-

I felt like more motivated to complete the lesson because I'm like, okay, I can get graded for doing this and like making sure I understand it and like a graded practice all in one. And it just kind of felt gratifying after I finished and got points.

Associating the grade with learning in these ways may show that Finley and Cameron internalized the value of the grade in the process of completing the lessons.

Based on phrases used by the participants above, such as by Finley: “I was doing something that was worthwhile” and by Cameron: “I can get graded for…making sure I understand…felt gratifying,” it could be argued that the grade in this situation moved towards autonomous extrinsic motivation. Yet other phrases used by the participants, such as by Ava: “gave me an incentive” and by Eddie: “opportunity to get more…points” may indicate that the grade functioned more as a controlled extrinsic motivator. This evidence indicates the grade may have fallen somewhere on the continuum from controlled extrinsic motivation to autonomous extrinsic motivation.

Theme 3

Despite some minor frustrations with the forums, the positive peer relationships and common struggles increased participants’ feelings of connectedness and supported their learning. The four categories for this theme included peer interactions aided in learning, positive peer connections, shared experiences, and forum frustrations. This theme led to the assertation that the forums fostered feelings of relatedness, ultimately improving participants’ motivation.

Peer interactions aided in learning

Participants expressed that interacting in the forums helped their understanding:

- Devin::

-

I could go and be like and ask my question and see if I understood how someone else worded it better than the lesson and make me like grasp the concept more.

- Blake::

-

If I had trouble learning with one thing, I could look through the classmates’ forums. And that helped me understand that lesson better.

These participants used the forums as a way to improve their learning on difficult topics.

Positive peer connections and shared experiences

Participants also expressed that the forums increased feelings of connectedness. For example, Eddie stated: “I think the forums give us a chance to kind of talk one on one with each other,” and “I definitely felt a sense of connection, especially when since we're all doing the same lesson.” In addition to improved connectedness, shared experiences helped reduce feelings of isolation. For example, multiple participants expressed feeling less isolated because of the forums:

- Eddie::

-

[The forums] made me feel more confident about the lesson that other people may have the same problem as me. And I'm not the only one.

- Ava::

-

[The forums] made me think like, wow, I'm not alone in being confused in this specific subject or I'm not the only one who doesn't understand this.

- Finley::

-

It was nice being able to see my classmates kind of struggling with the same thing because there's a certain time in cyber school where it just feels like everybody else is like, you're just detached from everybody else, and it feels like only you, like you're the only person going through this hard work and everything, and it just kind of makes it feel better, made me feel better knowing that I wasn't the only person having trouble with those topics sometimes.

Knowing that other participants were struggling in the same way helped increase feelings of confidence, according to Eddie, and helped decrease feelings of detachment, according to Finley.

Forum frustrations

Despite these positive effects, some participants noted frustration with the forums. In comparison to 73 codes relating to positive peer relationships and learning reinforcement from the forums, the number of forum frustrations expressed was very low, containing only 6 codes.

Discussion

Research question

The research question aimed to examine the effects of the intervention on participants’ autonomy, competence, and relatedness. The quantitative results showed a significant increase in competence and relatedness, but not in autonomy. The qualitative results indicated strong positive support for competence and relatedness. The support for autonomy was more ambiguous, with overlap between design components for autonomy and competence. In general, the multipage lesson structure, feedback features, and optional components supported autonomy and competence, the prior knowledge and grade for the lesson supported competence, and the forums supported relatedness.

Autonomy and competence

The multipage structure of the lessons with content chunking and scaffolding is consistent with research on autonomy and competence. Hartnett (2015) found that a lack of structure resulted in decreased feelings of competence, while Ryan and Deci (2020) indicated that “the need for competence is best satisfied within well-structured environments” (p. 2). Content chunking can improve retention (Ullah et al., 2015) and can reduce “overwhelming students with cognitive overload” (Jaiswal, 2019, p. 1076). Using scaffolding to aid learners’ movement through the zone of proximal development is a typical process used in research based on Vygotsky’s (1978) work. Scaffolding has also been used in research on motivation relating to improving self-regulation among mathematics students (Bell & Pape, 2014) and self-efficacy in web-based environments (Valencia-Vallejo et al., 2018). Research suggests that providing a felicitous environment for the psychological needs of autonomy and competence to thrive through a clear supportive structure and scaffolding can improve students' self-efficacy and confidence (Kapp, 2012; Kirchener et al., 2006; Rayburn et al., 2018).

The participants' descriptions of the feedback features within the lessons are also consistent with research on competence and autonomy. Participants’ desire to interact effectively within the lessons demonstrates White's (1959) effectance motivation and the internal psychological need for competence (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Appropriate challenge increases motivation (Huang et al., 2019), whereas insufficient feedback decreases feelings of competence (Yantraprakorn et al., 2018). The feedback features also gave participants’ authentic control in their environment, which is a catalyst for improved autonomy (Rayburn et al., 2018; Ryan & Deci, 2020). Schunk and DiBenedetto (2020) described self-regulatory behaviors: “monitoring performances, adapting one’s approach as needed, reflecting on one’s progress, and sustaining motivation for task completion” (p. 5). These align with participants’ explanations of the ability to gauge their own understanding, gain understanding with the feedback, and fix their work through the second chance provided.

The helpful, low pressure, and optimally challenging options described by the participants may have also improved autonomy and competence. Choice is a key element influencing motivation in learners (Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2020). Two different studies of motivation in online learners supported this finding based on their results: “autonomy can be encouraged by creating pathways that involve meaningful choice and limited extrinsic pressures” (Martin et al., 2018, p. 51) and “when a learner personally chooses an assignment topic to explore, autonomy may increase” (Durksen et al., 2016, p. 255). While authentic choice supports autonomy, Ryan and Deci (2000) suggested that optimal challenges provide a means for fulfilling competence. Researchers found support for this idea within the virtual environment and suggest that a design should “provide users with optimal challenges but not overwhelming obstacles in creating an individual’s competence satisfaction” (Huang et al., 2019, p. 604).

Competence

Activating prior knowledge can support students’ perceptions of competence (Li & Baker, 2018) and is a key element in learners’ acquisition of new knowledge (Gagne et al., 1992). Chen (2014) found “prior knowledge can determine how well learners acquire information from e-learning systems and ultimately influence their learning outcomes in e-learning systems” (p. 351). Other researchers have also found that taking steps to identify, trigger, and support prior knowledge retrieval helps the learning process (van Blankenstein et al., 2013; Wetzels et al., 2011).

Unlike prior knowledge supports, the effectiveness of a grade in improving feelings of competence and motivation has been discordant in research. Some researchers contended that although intended to be extrinsically motivating, evaluations in the form of grades can have a controlling significance, reducing motivation (Gagne & Deci, 2005; Ryan & Deci, 2020). Bourgeois and Boberg (2016) acknowledged the benefit of grades as a controlled extrinsic motivator, but clarified that their effectiveness may lessen over time. In contrast, other researchers found that negative feedback with grades did not undermine competence or decrease motivation (Weidinger et al., 2017). Still others have acknowledged that learners may internalize the importance of the grade in association with the meaningful content acquired, boosting the perception of competence, and causing the grade to serve as an autonomous extrinsic motivator (Rinfret et al., 2014; Wijsman et al., 2019). This research aligns with participant responses indicating their motivation fell between controlled and autonomous extrinsic motivation based on the grade.

Relatedness

The participant responses about the forums in the intervention are consistent with research about relatedness. In a study of motivation in virtual environments, the researchers found that “feeling connected with others in virtual worlds [links] to increased intrinsic motivation” (Huang et al., 2019, p. 604). Others have also suggested that these feelings of connectedness within an online course improve motivation in the learners (Martens et al., 2004). These findings likely stem from “an inbuilt propensity to feel a psychological sense of connectedness and belonging to other human beings” (Carr, 2020, p. 333), which is characterized by the need for social relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2020). Yet the satisfaction of relatedness may be more difficult to achieve in the online environment (Durksen et al., 2016), which is in line with some of the forum frustrations participants shared in this study.

Practical recommendations for online mathematics course design

The findings provide implications on motivational features for online mathematics course design. Both the quantitative and qualitative data supported the following three design features for improving competence in the participants: self-check buttons with informative and correctness feedback, prior knowledge explanations with self-check practice, and content chunking with scaffolding.

One way to incorporate feedback and provide an avenue for students to build appropriate confidence in their abilities is through self-check buttons on check for understanding questions throughout the lessons. Jeffery and Ahmad (2018) suggested that “informative feedback is often more important in an online environment than a traditional environment because students feel isolated due to a lack of nonverbal and visual signals” (Jeffery & Ahmad, 2018, p. 8). With a lack of these signals and proximate access to help, immediate feedback throughout the learning process becomes more important. Utilizing self-check buttons may be beneficial in asynchronous online mathematics courses and are now being integrated in the new Algebra 1 course at the school in this study.

Introducing prior knowledge in an asynchronous online environment improved participants’ motivation to complete the lesson. Presenting the prerequisite information, providing a check for understanding, and giving the option for informative and correctness feedback supported participants’ feelings of competence. These prior knowledge lesson features are also currently being integrated into the new Algebra 1 course.

Chunking and conceptual scaffolding with online mathematical content supported students' competence and acquisition of knowledge. These recommendations are further supported by cognitive load theory. Sweller (1994) suggests that mathematics tends to involve high element interactivity because much of the content is connected and needs to be understood together to build new schema. This high element interactivity increases intrinsic cognitive load, leaving less room for extraneous cognitive load (Sweller, 1994). Chunking, worked-out examples, and scaffolding can help reduce extraneous cognitive load (Ak, 2016; Sweller, 1994). The new Algebra 1 course at the school in this study is also now utilizing these chunking and scaffolding design features within the lesson structure.

Limitations and future research

Limitations of this study included possible bias or subjectivity because of the researcher’s insider role in the study (Herr & Anderson, 2005). The lack of anonymity and small number of interviewees may have affected the content of the interview responses (Mertler, 2017). The inductive analysis process of the interview transcripts can be subjective. With only one researcher involved in the coding process, independent analyses or evidence of inter-rater reliability was not present (Pyrczak & Tcherni-Buzzeo, 2019). Using a limited purposive sample may also mean that the results are unreliable (Pyrczak & Tcherni-Buzzeo, 2019) and not generalizable (Saldana, 2021), so the recommendations should be considered in light of specific context variations and requirements.

The findings and interpretations in this study left some questions unanswered. Although the design components for competence and relatedness were strongly supported by both the quantitative and qualitative results, the lesson features for autonomy were more ambiguous. Specifically, two areas arose that warrant further research based on the results of this study: the distinction between online lesson design components for autonomy and competence and the effect of choice on autonomy in online lesson design.

Conclusions

Since mathematics students at the school in this study lacked motivation to complete lessons, the goal of this action research was to improve student motivation levels using a self-determination theory-based online unit. Motivation was analyzed based on participants’ perceptions of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, as defined in self-determination theory. Both the quantitative and qualitative data indicated that students’ perceptions of competence and relatedness likely improved. Specific design components for competence that were strongly supported by the interviews included the check buttons, prior knowledge section, and chunking information with scaffolding throughout the lessons. The findings for autonomy were more ambiguous. No significant change was shown in the quantitative results, yet the qualitative responses seemed to support the satisfaction of autonomy. The participant responses in the interviews indicated that the design components for autonomy may have been confused with the design components for competence. Overall, the findings indicate that using a self-determination theory-based online unit helped improve students' motivation levels based on their perceptions of competence and relatedness, with specific design components for competence being particularly effective.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Ak, Ş. (2016). The role of technology-based scaffolding in problem-based online asynchronous discussion. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(4), 680–693. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12254

Bell, C. V., & Pape, S. J. (2014). Scaffolding the development of self-regulated learning in mathematics classrooms. Middle School Journal, 45(4), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/00940771.2014.11461893

Bourgeois, S. J., & Boberg, J. E. (2016). High-achieving, cognitively disengaged middle level mathematics students: A self-determination theory perspective. RMLE Online, 39(9), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404476.2016.1236230

Carr, S. (2020). Dampened motivation as a side effect of contemporary educational policy: A self-determination theory perspective. Oxford Review of Education, 46(3), 331–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2019.1682537

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., Duriez, B., Lens, W., Matos, L., Mouratidis, A., Ryan, R. M., Sheldon, K. M., Soenens, B., Van Petegem, S., & Verstuyf, J. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39(2), 216–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1

Chen, C. H. (2014). An adaptive scaffolding e-learning system for middle school students’ physics learning. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 30(3), 342–355. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.430

Cho, M. H., & Shen, D. (2013). Self-regulation in online learning. Distance Education, 34(3), 290–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2013.835770

Cordeiro, P., Paixao, M. P., & Lens, W. (2015). Perceived parenting and basic need satisfaction among Portuguese adolescents. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 18(62), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2015.62

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, D. J. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Sage.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Sage.

Davies, M., Pon, D., & Garavalia, L. S. (2018). Improving pharmacy calculations using an instructional design model. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 82(2), 144–151. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe6200

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum.

Durksen, T. L., Chu, M. W., Ahmad, Z. F., Radil, A. I., & Daniels, L. M. (2016). Motivation in a MOOC: A probabilistic analysis of online learners’ basic psychological needs. Social Psychology of Education, 19, 241–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-015-9331-9

Durksen, T. L., Way, J., Bobis, J., Anderson, J., Skilling, K., & Martin, A. J. (2017). Motivation and engagement in mathematics: A qualitative framework for teacher-student interactions. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 29(2), 163–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13394-017-0199-1

Froiland, J. M., Davison, M. L., & Worrell, F. C. (2016). Aloha teachers: Teacher autonomy support promotes Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander students’ motivation, school belonging, course-taking and math achievement. Social Psychology of Education, 19(4), 879–894. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-016-9355-9

Gagne, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 331–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.322

Gagne, R. M. (1985). The conditions of learning and theory of instruction (4th ed.). Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Gagne, R. M., Briggs, L. J., & Wager, W. W. (1992). Principles of instructional design (4th ed.). Harcourt Brace College Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.4140391011

Haerens, L., Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., Soenens, B., & Van Petegem, S. (2015). Do perceived autonomy-supportive and controlling teaching relate to physical education students’ motivational experiences through unique pathways? Distinguishing between the bright and dark side of motivation. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16(3), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.08.013

Hartnett, M. (2015). Influences that undermine learners’ perceptions of autonomy, competence and relatedness in an online context. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 31(1), 86–99. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1526

Herr, K., & Anderson, G. L. (2005). The action research dissertation. Sage.

Hew, K. F. (2016). Promoting engagement in online courses: What strategies can we learn from three highly rated MOOCS. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(2), 320–341. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12235

Hsu, H. C. K., Wang, C. V., & Levesque-Bristol, C. (2019). Reexamining the impact of self-determination theory on learning outcomes in the online learning environment. Education and Information Technologies, 24(3), 2159–2174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-09863-w

Huang, Y. C., Backman, S. J., Backman, K. F., McGuire, F. A., & Moore, D. (2019). An investigation of motivation and experience in virtual learning environments: A self-determination theory. Education and Information Technologies, 24, 591–611. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-018-9784-5

Jacobi, L. (2018). What motivates students in the online communication classroom? An exploration of self-determination theory. Journal of Educators Online. https://doi.org/10.9743/jeo.2018.15.2.1

Jaiswal, P. (2019). Using learner-centered instructional approach to foster students’ performances. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 9(9), 1074–1080. https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0909.02

Jeffery, M., & Ahmad, A. (2018). A conceptual framework for efficient design of an online operations management course. Journal of Educators Online. https://doi.org/10.9743/jeo.2018.15.3.5

Kapp, K. (2012). The gamification of learning and instruction: Game-based methods and strategies for training and education. Wiley.

Keller, J. M. (2016). Motivation, learning, and technology: Applying the ARCS-V motivation model. Participatory Educational Research, 3(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.17275/per.16.06.3.2

Kim, B. (2015). Designing gamification in the right way. American Library Association, 51(2), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.24983/scitemed.aohns.2019.00109

Kirchener, P., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41, 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102

Lambert, J. (2017). An examination of the relationship between higher education learning environments and motivation, self-regulation, and goal orientation. Cognition and Learning, 10, 289–312.

Lee, J., & Martin, L. (2017). Investigating students’ perceptions of motivating factors of online class discussions. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 18(5), 148–172. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i5.2883

Leong, K. E., Tan, P. P., Lau, P. L., & Yong, S. L. (2018). Exploring the relationship between motivation and science achievement of secondary students. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 26(4), 2243–2258.

Li, Q., & Baker, R. (2018). The different relationships between engagement and outcomes across participant subgroups in massive open online courses. Computers and Education, 127, 41–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.08.005

Malone, T. W. (1981). Toward a theory of intrinsically motivating instruction. Cognitive Science, 5(4), 333–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0364-0213(81)80017-1

Martens, R., Gulikers, J., & Bastiaens, T. (2004). The impact of intrinsic motivation on e-learning in authentic computer tasks. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 20(5), 368–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2004.00096.x

Martin, N. I., Kelly, N., & Terry, P. C. (2018). A framework for self-determination in massive open online courses: Design for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 34(2), 35–55. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3722

Mertler, C. A. (2017). Action research: Improving schools and empowering educators (5th ed.). Sage.

Milman, N. B. (2017). Designing asynchronous online discussions for quality interaction in asynchronous online courses. Distance Learning, 14(3), 61–63.

Myers, M. D., & Newman, M. (2007). The qualitative interview in IS research: Examining the craft. Information and Organization, 17(1), 2–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2006.11.001

Polat, H., & Oz, R. (2017). Use of the distributed cognition theory in a lesson plan: A theory, a model and a lesson plan. Erzincan University Journal of Education Faculty, 19(3), 180–190. https://doi.org/10.17556/erziefd.341974

Proulx, J. N., Romero, M., & Arnab, S. (2017). Learning mechanics and game mechanics under the perspective of self-determination theory to foster motivation in digital game based learning. Simulation and Gaming, 48(1), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878116674399

Pyrczak, F., & Tcherni-Buzzeo, M. (2019). Evaluating research in academic journals: A practical guide to realistic evaluation (7th ed.). Routledge.

Qian, Y., & Sun, Y. (2019). Autonomous learning of productive vocabulary in the EFL context: An action research approach. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 34(1), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqy026

Rayburn, S. W., Anderson, S. T., & Smith, K. H. (2018). Designing marketing courses based on self-determination theory: Promoting psychological need fulfillment and improving student outcomes. Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education, 26(2), 22–32.

Rinfret, N., Tougas, F., Beaton, A. M., Laplante, J., Ngo Manguelle, C., & Lagacé, M. C. (2014). The long and winding road: Grades, psychological disengagement and motivation among female students in (non-)traditional career paths. Social Psychology of Education, 17(4), 637–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-014-9271-9

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-2004-22201

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Sagor, R. (2000). Guiding school improvement with action research. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Saldana, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (4th ed.). Sage.

Schunk, D. H., & DiBenedetto, M. K. (2020). Motivation and social cognitive theory. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 60, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.101832

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. Macmillan.

Strauss, A. L. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge University Press.

Sun, J. C. Y., & Rueda, R. (2012). Situational interest, computer self-efficacy and self-regulation: Their impact on student engagement in distance education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(2), 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01157.x

Sweller, J. (1994). Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design. Learning and Instruction, 4(4), 295–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/0959-4752(94)90003-5

Taber, K. S. (2018). The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education, 48(6), 1273–1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2

Tamborini, R., Bowman, N. D., Eden, A., Grizzard, M., & Organ, A. (2010). Defining media enjoyment as the satisfaction of intrinsic needs. Journal of Communication, 60(4), 758–777. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01513.x

Tang, H. (2021). Person-centered analysis of self-regulated learner profiles in MOOCs: A cultural perspective. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69(2), 1247–1269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-09939-w

Tang, H. (2024). Understanding self-regulated learning and learner performance in MOOCs. Distance Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2024.2338712

Tang, H., & Bao, Y. (2022). Profiles of self-regulated learners in MOOCs: A cluster analysis based on a Rasch model. Interactive Learning Environments. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2129394

Tang, H., Lin, Y., & Qian, Y. (2020). Understanding K-12 teachers’ intention to adopt Open Educational Resources: A mixed methods inquiry. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(6), 2558–2572. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12937

Tang, H., Lin, Y., & Qian, Y. (2021). Improving k-12 teachers’ acceptance of open educational resources by open educational practices: A mixed methods inquiry. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69(6), 3209–3232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-10046-z

Tang, H., Xing, W., & Pei, B. (2018). Exploring the temporal dimension of forum participation in Massive Open Online Courses. Distance Education, 39(3), 353–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2018.1476841

Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748

Thompson, C. J., Leonard, L., & Bridier, N. (2019). Online discussion forums: Quality interactions for reducing statistics anxiety in graduate education students. International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education, 34(1), 1–31.

Ullah, H., Rehman, A. U., & Bibi, S. (2015). Gagne’s 9 events of instruction: A time tested way to improve teaching. Pakistan Armed Forces Medical Journal, 65(4), 535–540.

Valencia-Vallejo, N., López-Vargas, O., & Sanabria-Rodríguez, L. (2018). Effect of motivational scaffolding on e-learning environments: Self-efficacy, learning achievement, and cognitive style. Journal of Educators Online, 15(1), 1–15.

van Blankenstein, F. M., Dolmans, D. H. J. M., van der Vleuten, C. P. M., & Schmidt, H. G. (2013). Relevant prior knowledge moderates the effect of elaboration during small group discussion on academic achievement. Instructional Science, 41(4), 729–744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-012-9252-3

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher mental process. Harvard University Press.

Wang, Y. M. (2019). Enhancing the quality of online discussion-assessment matters. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 48(1), 112–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239519861416

Weidinger, A. F., Steinmayr, R., & Spinath, B. (2017). Math grades and intrinsic motivation in elementary school: A longitudinal investigation of their association. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 87(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12143

Wetzels, S. A. J., Kester, L., Van Merri, J. J. G., & Broers, N. J. (2011). The influence of prior knowledge on the retrieval-directed function of note taking in prior knowledge activation. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 274–291. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709910X517425

White, R. W. (1959). Motivation reconsidered: The concept of competence. Psychological Review, 66(5), 297–333. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040934

Wiebe, E., Durepos, G., & Mills, A. J. (2010). Encyclopedia of case study research. Sage.

Wijsman, L. A., Saab, N., Schuitema, J., van Driel, J. H., & Westenberg, P. M. (2019). Promoting performance and motivation through a combination of intrinsic motivation stimulation and an extrinsic incentive. Learning Environments Research, 22(1), 65–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-018-9267-z

Wilkie, K. J., & Sullivan, P. (2018). Exploring intrinsic and extrinsic motivational aspects of middle school students’ aspirations for their mathematics learning. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 97(3), 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-017-9795-y

Yantraprakorn, P., Darasawang, P., & Wiriyakarun, P. (2018). Self-efficacy and online language learning: Causes of failure. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 9(6), 1319. https://doi.org/10.17507/jltr.0906.22

Zhang, M., Du, X., Hung, J., Li, H., Liu, M., & Tang, H. (2022). Analyzing and interpreting student’s self-regulated learning patterns–combining time-series feature extraction, segmentation and clustering. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 60(5), 1130–1165. https://doi.org/10.1177/07356331211065097

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Brian Cote for allowing us to conduct this research project at the twenty-first century Cyber Charter School and supporting us through the process. Thank you to the mathematics teachers, instructional design team, and administrators for your collaboration on this project.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Carolinas Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is not any potential conflict of interest in the work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shank, E., Tang, H. & Morris, W. Motivation in online course design using self-determination theory: an action research study in a secondary mathematics course. Education Tech Research Dev (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-024-10410-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-024-10410-9