Abstract

Previous research has studied effective self-protective behaviors, such as a victim’s physical resistance leading to the avoidance of sexual victimization. However, there are few studies on effective self-protective behavioral sequences, such as an offender’s physical violence followed by the victim’s physical resistance. Our study aims to clarify these sequences through a supervised machine learning approach. The samples consisted of 88 official documents on sexual assaults involving women, committed by male offenders incarcerated in a Japanese local prison. These crimes were classified as completed or attempted cases based on judges’ evaluations. All phrases in each crime description were also partitioned and coded according to the Japanese Penal Code. The support vector machine identified the most likely sequences of behaviors to predict completed and attempted cases. Approximately 90% of cases were correctly predicted through the identification of behavior sequences. The sequence involving an offender’s violence followed by the victim’s physical resistance predicted attempted sexual assault. However, the sequence involving a victim’s general resistance followed by the offender’s violence predicted completed sexual assault. Victims’ and offender’s behaviors need to be interpreted from behavioral sequence perspectives rather than a single action perspective. The supervised machine learning methodologies may extract self-protective behavioral sequences in documents more effectively than other methodologies. The self-protective sequence is a fundamental part of resistance during sexual assault. Training focused on protective sequence contributes to the improvement of resistance training and rape avoidance rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sexual assault violates the victim’s human rights and needs to be prevented. For this purpose, several protective actions have been proposed for potential victims (Ullman 2007). Among these protective actions, the most convincing strategy is physical resistance, namely physical action against offenders such as fighting, fleeing, guarding one’s body with one’s arm, and struggling (Clay-Warner 2002; Sarnquist et al. 2014; Senn et al. 2015; Tark and Kleck 2014). The second effective strategy is forceful verbal resistance, which refers to a verbal response that leaves no room for the offender to talk, including screaming, yelling, and swearing at the offender (Clay-Warner 2002; Tark and Kleck 2014; Ullman 2007; Zoucha-Jensen and Coyne 1993). The third strategy is nonforceful verbal resistance, which is a verbal response that leaves some room for the offender to talk, including reasoning, arguing, persuading, or appeasing the offender (Fisher et al. 2007). University women who received training in the first and second strategies had a reduced risk of sexual victimization compared with those who did not (Senn et al. 2015). The third strategy of nonforceful verbal resistance was especially effective for child victims (Leclerc et al. 2011b) and in cases of sexual assault that did not involve physical violence on the part of the offender (Fisher et al. 2007).

Although these protective actions were well reported (Senn et al. 2015), behaviors before and after the protective actions were still unclear. On the one hand, a victim’s protective actions paired with an offender’s behavior were reportedly effective in decreasing the risk of sexual victimization (Fisher et al. 2007; Ullman 1998): Physical resistance of the victim following an offender’s physical violence was effective in reducing the risk of sexual victimization. Similarly, forceful verbal resistance of the victim following an offender’s verbal coercion was effective in reducing the risk. On the other hand, other studies suggested that an offender’s physical violence following a victim’s resistance increased the risk of sexual victimization, because the offender’s violence ended the victim’s resistance (Balemba et al. 2012; Jordan 2005). Hence, an offender’s antecedent violence and the victim’s consequent physical resistance may reduce the risk of sexual victimization, whereas a victim’s antecedent resistance and the offender’s consequent violence may increase the risk of sexual victimization. Yet, direct comparison of these behavioral sequences was rare; therefore, the behavioral sequences of protective action remained unclear.

Our study aims to clarify the behavioral sequences of protective actions. We seek to identify the behavioral sequence that predicts completed or attempted (but not completed) sexual assaults. To clarify the sequence, we focused on behavioral interactions between the victim and the offender during a sexual assault. A specific interaction that predicts an attempted sexual assault is regarded as a protective behavioral sequence to avoid victimization. Another interaction that predicts a completed sexual assault is regarded as a predictive behavioral sequence for victimization. Both protective and predictive sequences clarify knowledge about sequences of protective action and are beneficial for protective action training (Senn et al. 2013).

Previous study also suggested that victims’ protective actions, offenders’ behaviors, and the effects of protective actions were different for women and child victims. Child victims received more gifts from offenders (Leclerc and Wortley 2015; Leclerc et al. 2011a), used nonforceful verbal resistance more (Leclerc et al. 2010), and protected themselves less efficiently (Finkelhor et al. 1995a, b) than women victims. To clarify the behavioral sequence of protective action, victims of the same generation group are desirable. Hence, we excluded child-victim cases. We regarded those younger than 13 years as children according to Japanese law (Maeda 2015) and excluded cases that included child victims, although the definition of a child varies in different countries and eras (Finkelhor et al. 1995a; Leclerc and Wortley 2015).

Further, to label sexual assaults as completed and attempted cases, we utilized official suit documents on sexual assault in Japan. An attempted assault has a less severe penalty than a completed assault in Japan (Yamashita and Yamaguchi 2016), so the terms for these attempts are clearly described in the documents. Furthermore, the documents also describe behavioral chains between an offender and a victim during the assault. The described interaction was useful for clarifying behavioral sequences of the crime.

Based on the label of the assault (completed or attempted) and behavioral sequences in the documents, we tested four hypotheses. To confirm previous findings on protective action (Leclerc et al. 2011b; Senn et al. 2015), the victim’s physical resistance, forceful verbal resistance, and nonforceful verbal resistance would predict attempted sexual assault (Hypothesis 1). According to the parity effects of protective action (Fisher et al. 2007; Ullman 1998), the offender’s antecedent physical violence and the victim’s consequent physical resistance would predict attempted sexual assault (Hypothesis 2). Similarly, the offender’s antecedent verbal coercion and the victim’s consequent forceful verbal resistance would predict attempted sexual assault (Hypothesis 3). According to the effect of the offender’s physical violence on the victim’s resistance (Balemba et al. 2012; Jordan 2005), the victim’s antecedent resistance and the offender’s consequent physical violence would predict sexual victimization (Hypothesis 4).

Our study utilized supervised machine learning models as a statistical model. This was because the number of behavioral sequences increases the number of variables exponentially and destroys the premise of psychological statistical analysis: The 0, 1, and 2 behavioral sequences in our study require 18, 324, and 5832 variables. The 324 and 5832 independent variables did not fit well with regression analysis for the prediction of binary-dependent data (completed or attempted). In contrast, the support vector machine in supervised machine learning is robust against an increased number of variables (Bishop 2006); therefore, we used the support vector machine as in other studies (Costa et al. 2017), which predict a binary-dependent data (success or failure) through lots of independent variables.

Methods

Sample

We identified 128 sexual assault cases consisting of 72 male inmates who were imprisoned as repeat offenders in April 20XX in a local Japanese prison. Among them, 12 cases were inaccessible, because of the offenders’ transportation to another prison; in addition, 28 cases involved child victims (younger than 13 years old). Thus, these cases were excluded from the analysis. Finally, we analyzed 88 sexual assault cases. Of these, 35 involved teen victims (aged between 13 and 19 years) and 52 involved adult victims (aged over 20 years). One case included a charge of public lewdness in his car on the road; therefore, the victim’s exact age was unknown, but many victims could be adult drivers rather than children in passenger seats.

Measures

Categories of Sexual Assault

Table 1 shows the four categories of sexual assault included in our study: completed rape, attempted rape, completed sexual coercion, and attempted sexual coercion. Although the definitions of rape and sexual coercion differ slightly in previous studies (Clay-Warner 2002; Fisher et al. 2007; Ullman and Knight 1992), we utilized the Japanese Penal Code to fit with the finalized criminal suit documents in Japan. Completed rape is an offender’s realization of penile-vaginal penetration achieved by either or both illegal physical force and verbal coercion (Maeda 2015; Yamashita and Yamaguchi 2016). Attempted rape does not involve realization of penile-vaginal penetration but includes the offender’s intent of penile-vaginal penetration. For instance, in a case in which the offender exposed his private parts to a victim and penetrated her vagina with his finger in her private room, the Japanese judges regarded the offender as having the intent of penile-vaginal penetration and wrote “rape” in the section for the charged offense and “with intention to rape” in the criminal behavior description section.

Completed sexual coercion involves any sexual behavior other than penile-vaginal penetration achieved by either or both illegal physical force and verbal coercion (Maeda 2015; Yamashita and Yamaguchi 2016). Further, completed sexual coercion did not involve an offender’s intent of penile-vaginal penetration (Table 1). In a case in which the offender touched the victim’s breast in a public train in the presence of many passengers, the Japanese judges did not regard the offender as having the intent of penile-vaginal penetration, so the judges never wrote the term “rape” in the documents. Attempted sexual coercion does not involve the realization of any sexual behavior but includes the offender’s intent of sexual behavior. For instance, in a case in which the offender prepared a spy camera in his bathroom and forced his victim to take a shower, and she noticed the camera before taking the shower, the judges regarded the offender as having the intent of sexual behavior that was not realized. Hence, they wrote “attempted” in the section for the charged offense and “failed to accomplish one’s purpose” in the criminal behavior description section. Based on these descriptions, we categorized cases as completed rape (n = 24), attempted rape (n = 13), completed sexual coercion (n = 49), and attempted sexual coercion (n = 2).

Code of Behaviors

All phrases in the criminal description were partitioned. In total, 560 phrases were coded according to the following definitions.

Victim’s Resistance

Physical resistance is physical action against an attacker (Clay-Warner 2002). Forceful verbal resistance refers to a verbal response leaving no room for the offender to talk (Ullman 2007). Nonforceful verbal resistance refers to a verbal response leaving some room for the offender to talk (Fisher et al. 2007). Several phrases included “resist” (n = 5) or “fierce resistance” (n = 1) only; these phrases cannot be regarded as a specific type of resistance, so they were coded as general resistance. Table 2 shows the details of victims’ resistant behaviors.

Offender’s Behavior

Sexual behavior is a behavior that “unnecessarily stimulates and excites sexual desires,” “harms the grace of a citizen,” and “is against sexual morality” (Maeda 2015), as defined in the sections on Rape, Forcible Indecency, and Public Indecency in the Japanese Penal Code (Yamashita and Yamaguchi 2016). Physical violence is defined as the illegal use of physical force, regardless of physical contact (Maeda 2015), in the Assault section of the Japanese Penal Code (Yamashita and Yamaguchi 2016). Verbal coercion is defined as “intimidating another through a threat to another’s life, body, freedom, reputation, or property” in the Intimidation section (Yamashita and Yamaguchi 2016) and “causes the other to perform an act which the other person has no obligation to perform, or hinders the other from exercising his or her rights” in the Compulsion section (Yamashita and Yamaguchi 2016). Persuasion (nonforceful verbal behavior) is verbal communication without threat and compulsion. Table 2 shows details of offenders’ behavior during the crime.

The transfer of possessions is defined as transferring others’ property against their will (Maeda 2015) in the Theft and Robbery sections (Yamashita and Yamaguchi 2016). Although there are various types of property (Maeda 2015), we focused on the transfer of money only to clarify mercenary motives. Here, offenders obtained the victim’s cash (n = 5), cash card (n = 1), or credit card (n = 1).

Crime Location

The location of the encounter was categorized according to indoor/outdoor and private/semipublic/public criteria (Beauregard et al. 2007). Private refers to a privately owned site not open to the public. Semipublic refers to a privately owned site open to the public, especially for business purposes. Public is a publicly owned site. An indoor private location includes the victim’s home (n = 31), hotel room (n = 9), victim’s and offender’s homes (n = 9), offender’s home (n = 3), and someone else’s home (n = 3). Indoor semipublic locations include elevators (n = 2), plastic greenhouses (n = 2), restaurants (n = 2), trash areas (n = 2), bars (n = 1), cafes (n = 1), and toilets in an apartment (n = 1). Indoor public locations include toilets in the park (n = 2), cars on the road (n = 3), and trains (n = 2). Outdoor private locations include the property around someone’s home (n = 4) and a school (n = 1). Outdoor semipublic locations include parking lots (n = 5), stations (n = 2), fields (n = 2), corridors in an apartment (n = 2), and buildings (n = 2). The entrance to an apartment (n = 1), escalator in a building (n = 1), and stairs in a building (n = 1) are also included. Outdoor public locations include roads (n = 12) only.

The approach to the crime location was coded as “Invade” and “Go with.” “Invade” means that the offender approached the victim’s private location alone (Leclerc et al. 2016), invading the victim's private space through an open door (n = 8), through an open window (n = 8), through a window (n = 4), through the door (n = 3), or through a vent (n = 1). In addition to these numbers, six offenders invaded the victim’s home, but their invasion methods are unknown. “Go with” means that the offender moved to the crime location with the victim (Leclerc et al. 2016), bringing the victim (n = 14) or moving the victim in his car (n = 1) or taxi (n = 1). In addition to these numbers, two offenders moved with the victim, but their transportation is unknown (n = 2).

Bystander

A bystander is an individual present, who is not the victim or offender: “a third person detected the crime (n = 2)” and “a third person (n = 1) and the victim’s sibling (n = 1) came to the situation.”

Coding Process

The following case is a dummy attempted rape case: “The offender invaded the victim’s house through an open window, saying, ‘I will kill you if you make a noise.’ The offender then touched the victim’s private parts and tried to have sexual intercourse with her; however, she fled, meaning that he failed to accomplish his purpose.” When we code this case, the code can be “offender’s invasion → a victim encounters the offender in a private indoor setting → offender’s verbal coercion → offender’s sexual behavior → offender’s sexual behavior → victim’s physical resistance → offender’s failure to achieve the goal.”

Sequence 1 (two continuous behaviors) includes “Invade → Private Indoor”; “Private Indoor → Verbal Coercion”; and “Physical Resistance → Failure to achieve goal.” Here, the sequence with “Failure to achieve goal” is excluded from the analysis, because this is the classification criterion of an attempted case. The selected sequences were linked to the attempted class, and these sequences were weighted to predict the attempted class. Similarly, all cases were used, and the support vector machine learned the weights of the sequences. The final weights of these sequences show the most predictive sequences.

Plan of Analysis

To show the probability of the behavioral sequence, conditional probability was applied. Further, to predict attempted and completed cases through a behavioral sequence, the Linear Support Vector Classifier was used in scikit-learn 0.18.1. The results of prediction have four categories: A true positive (TP) indicates that both the judge and classifier supported the completed sexual assault, while a false positive (FP) indicates that the classifier supported the completed sexual assault, but the judge did not. Furthermore, a false negative (FN) indicates that the judge supported the completed sexual assault, but the classifier did not support it, while a true negative (TN) indicates that neither the judge nor the classifier supported the completed sexual assault. To evaluate the results of prediction, we utilized the index of accuracy: Accuracy is (TP + FN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN). For the validation of accuracy, the 10-fold cross-validation is utilized: The total sample (N = 88) is randomly partitioned into 10 equal-sized subsamples (n = 8 or 9). A single subsample is retained as test data, whereas the other subsamples are used as training data (9 subgroups, n = 79 or 80). With the training data, the predictive model (sequence weight) is estimated. The model analyzes retaining test data as a test and provides accuracy. Next, another single subsample is selected as test data; the other subsamples are training data, and the model provides accuracy. By repeating this method, we can test 10 models and provide 10 accuracies. The average of 10 accuracies indicates robust accuracy of the total sample.

Results

Comparison of Rape and Sexual Coercion Cases

Table 3 shows several significant differences between the rape and sexual coercion cases. Victims in sexual coercion cases were attacked by unknown strangers more frequently than those in rape cases. The rate of completed sexual coercion cases is also higher than the rate of completed rape cases. In contrast, victims used physical resistance and general resistance in rape cases more frequently than those in sexual coercion cases. Furthermore, rape cases occurred in indoor private settings more frequently than sexual coercion cases. Except for these indexes, rape and sexual coercion did not differ in other indexes such as those associated with victims’ and offenders’ ages.

Interconnections of Victim’s Protective Action and Offender’s Failure of Sexual Assault

Table 4 shows the conditional and unconditional probabilities of offenders’ behaviors and victims’ protective actions. The probabilities in rape and sexual coercion cases were quite similar; therefore, Table 4 shows the combined probabilities only. Table 4 shows that the chance of consequent rape (sexual coercion) avoidance is predicted by the victim’s antecedent physical resistance (38%), forceful verbal resistance (33%), nonforceful verbal resistance (11%), general resistance (83%), and bystander’s intervention (75%). The unconditional chance of consequent rape (sexual coercion) avoidance is 3%, meaning that these victims’ antecedent-resistant behaviors and bystanders’ interventions increased the chance of successfully thwarting rape (or sexual coercion) completion.

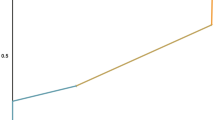

Furthermore, victims’ resistance behaviors and bystanders’ interventions were connected with each other. Figure 1 shows the interconnections between the victim’s protective action and the offender’s failure of sexual assault. The victim’s physical resistance increased the chance of the victim’s forceful verbal resistance. The victim’s forceful verbal resistance increased the probabilities of the victim’s nonforceful verbal resistance and a bystander’s intervention. Furthermore, a bystander’s intervention increased the probability of the victim’s physical resistance. All victim resistance and bystander intervention increased the probability of the offender’s failure of sexual assault. Figure 1 indicates that protective actions were connected with each other and had both direct and indirect effects on increasing the probability of the offender’s failure of sexual assault.

Interconnections between victims’ protective action and offenders’ failure of sexual assault. Behaviors shown at the start point and end point of the arrow indicate antecedent and consequent behaviors, respectively. The right value indicates the unconditional probability of the consequent behavior. The left value indicates conditional probability of the consequent behavior under the condition of the antecedent behavior

Prediction Accuracy of Attempted and Completed Sexual Assault with Behavioral Sequence

We used 0 (single behavior), 1 (two continuous behaviors), and 2 sequences (three continuous behaviors) as sequence units and built models to predict completed and attempted cases. Table 5 shows the prediction accuracies of the models. All accuracies were over 80%. Especially, models in rape cases show over 88%. Taking into account random chances (if classifier learns only the average rate of completed rape and randomly predict the rate of completed rape, the classifier’s accuracy of completed rape could be the average rate (64.9%, Table 3)), the sequence of continuous behavior effectively predicted rape avoidance.

Protective Sequence for Avoiding Sexual Victimization (Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3)

Table 6 shows the protective sequence for avoiding sexual victimization. As hypothesized (1), attempted sexual assault was predicted by the victim’s general resistance (0 sequence 1st place w = − 2.00), physical resistance (0 sequence 3rd place w = − 1.54), forceful verbal resistance (0 sequence 2nd place w = − 1.76), and nonforceful verbal resistance (0 sequence 7th place w = − 0.17). Moreover, as expected (2), the sequence of offender’s antecedent violence and victim’s consequent physical resistance was also protective for avoiding sexual victimization (1 sequence 6th place: w = − 1.00, 2 sequence 4th place: w = − 0.82). Similarly, the sequence of offender’s antecedent verbal coercion and victim’s consequent forceful verbal resistance was also protective for avoiding sexual victimization (1 sequence 3rd place: w = − 1.20, 2 sequence 3rd place: w = − 1.18) [Hypothesis 3]. Further, victim’s general resistance after offender’s sexual behavior is also protective for avoiding sexual victimization (1 sequence 1st place: w = − 2.09, 2 sequence 1st place: w = − 2.11).

Predictive Sequence for Sexual Victimization (Hypothesis 4)

Table 7 shows the predictive sequence for sexual victimization. As hypothesized (4), the sequence of victim’s antecedent general resistance and offender’s consequent violence was predictive for sexual victimization (1 sequence 2nd place: w = 0.76, 2 sequence 8th place: w = 0.26). Further, offender’s antecedent violence and offender’s consequent sexual behavior were predictive for sexual victimization (1 sequence 1st place: w = 0.88, 2 sequence 1st place w = 0.40). Table 4 also shows that an indoor public setting is predictive for sexual victimization (0 sequence 1st place w = 1.09). These findings suggest that a victim’s physical resistance in response to an offender’s antecedent physical contact was protective in avoiding sexual victimization. However, an offender’s physical contact in response to a victim’s antecedent resistance was predictive for sexual victimization.

Discussion

Protective Action for Avoiding Sexual Victimization (Hypothesis 1)

Our study confirmed the effects of protective action for avoiding sexual victimization. In line with environmental criminology theory (Braga 2005; Clarke 1997; Cornish and Clarke 2014; Felson and Clarke 1998; Guerette and Santana 2010), we confirmed that physical resistance was the effective protective action for avoiding sexual victimization. Physical resistance requires that offenders expend additional energy, for example, to catch the victim again, and pose additional risk such as injury to the offender (Guerette and Santana 2010). This energy and risk may be effective in reducing the potential for sexual victimization. Effects of physical resistance were mainly reported in North America (Clay-Warner 2002; Fisher et al. 2007; Senn et al. 2015; Tark and Kleck 2014; Ullman 2007) with a few exceptions (Sarnquist et al. 2014). Our findings with a Japanese sample confirmed generalizability of previous findings to the Asian population. We also found that the effects of forceful verbal resistance were comparable to the effects of physical resistance, similar to previous studies (Clay-Warner 2002; Zoucha-Jensen and Coyne 1993). Interconnections between the victim’s protective action and offender’s failure of sexual assault suggested indirect effects of forceful verbal resistance (Fig. 1). The antecedent victim’s forceful verbal resistance was linked to consequent bystander intervention and the victim’s nonforceful verbal resistance, both of which increased the chance of avoiding sexual victimization. Forceful verbal resistance adds to the cost of the crime, such as clear resistance from the potential victim during the initial step, and may add other costs to the crime, such as being caught by bystanders, in the second step. The two-step effects of forceful verbal resistance may make the total effect comparable to the effects of physical resistance. We also found that the victim’s nonforceful resistance was effective for avoiding sexual victimization, but the effect size of the victim’s nonforceful resistance was smaller than the effect size of the victim’s physical resistance and forceful verbal resistance. One reason stems from sample differences. Our study did not include child-victim cases for whom nonforceful verbal resistance was effective (Leclerc et al. 2011b); therefore, nonforceful resistance may not show the protective effects seen in a previous study. Our study also includes rape victims who preferred physical resistance (Fisher et al. 2007), so the effects of physical resistance might be expanded, whereas the effects of nonforceful resistance might be diminished.

Parity Between Victim’s Protective Action and Offender’s Criminal Behaviors Predicted Attempted Sexual Assault (Hypotheses 2 and 3)

As hypothesized (2), the sequence of offender’s antecedent violence and victim’s consequent physical resistance was effective for avoiding sexual victimization. The sequence of offender’s antecedent verbal coercion and victim’s consequent forceful physical resistance was effective for avoiding sexual victimization (Hypothesis 3). Moreover, the sequence of offender’s antecedent sexual behavior and victim’s consequent physical resistance was effective for avoiding sexual victimization. These findings clarified the temporal order of parity between an offender’s antecedent physical contact and the victim’s consequent physical resistance (Fisher et al. 2007; Nurius and Norris 1996; Ullman 1998). A victim’s physical resistance in response to an offender’s antecedent physical contact might prevent the offender’s additional criminal behaviors and decrease the potential for sexual victimization. Similarly, a victim’s forceful verbal resistance in response to an offender’s antecedent verbal coercion might prevent the offender’s additional criminal behaviors and decrease the potential for sexual victimization.

Predictive Sequence for Sexual Victimization (Hypothesis 4)

As hypothesized (4), the sequence of victim’s antecedent general resistance and offender’s consequent violence predicted sexual victimization (w = 0.76). The sequence of offender’s antecedent violence and offender’s consequent sexual behavior predicted sexual victimization. Taking into account the small effect size of single violence (w = 0.17), the offender’s violence needs to be interpreted along with the antecedent and consequent behaviors of his violence. The offender’s violence followed by his sexual behavior on a victim could predict sexual victimization, because his violence could prevent additional resistance from the victim (Jordan 2005). In contrast, an offender’s violence followed by the victim’s physical resistance could predict avoidance of sexual victimization, because his violence causes a counterattack from the victim and increases the cost of the crime (Fisher et al. 2007).

Limitations

Our study has limitations regarding sample and behavioral coding. First, the number of the sample is too small for machine learning approach (Pang et al. 2002; Tong and Koller 2001), so our findings are preliminary and require caution in interpretation. Moreover, our sample did not include child-victim cases; therefore, protective actions and sequences for avoiding sexual victimization were unknown in child-victim cases. A previous study suggested that child-victims’ physical resistance might have adverse effects on sexual victimization (Finkelhor et al. 1995a, b) and their nonforceful verbal resistance could be effective in reducing the risk of sexual victimization (Leclerc et al. 2011b). Future study should sample a number of child-victim cases. Second, our behavioral coding was based on criminal suit documents; the criminal documents focused on criminal behaviors, so several noncriminal behaviors might not have been described well, such as giving gifts and playing games, although they were popular offenders’ strategies to complete sexual assault (Leclerc et al. 2016). The documents were also written by individual judges. The description of the crime situation could be changed by judges (Zaleski et al. 2016). In fact, several victims’ resistant behaviors were described only as “resistance,” which cannot lead to categorization of specific resistant behavior. Individual differences of judges need to be controlled in the future.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, our supervised machine learning model including victims’ and offenders’ behaviors during sexual assault clarified the protective sequence for avoiding sexual victimization. We summarize three points. First, the sequence of an offender’s antecedent violence and a victim’s consequent physical resistance was an effective protective action, but the sequence of a victim’s antecedent resistance and an offender’s consequent violence was predictive for sexual victimization. Hence, protective training needs to include a lecture on how to restrain an offender’s counterattack. Second, forceful verbal resistance was especially effective after an offender’s verbal coercion. Hence, an offender’s verbal coercion could be a sign to use forceful verbal resistance. Third, our model showed protective sequences for avoiding sexual victimization, which were not clarified by predominant methodology. The use of supervised machine learning models with other official criminal documents, such as murder and robbery cases, could discover protective sequences to avoid these crimes. The protective sequence is a fundamental part of resistance during sexual assault (Senn et al. 2013, 2015). Training focused on protective sequence contributes to the improvement of resistance training and rape avoidance rates (Senn et al. 2015).

References

Balemba, S., Beauregard, E., & Mieczkowski, T. (2012). To resist or not to resist?: the effect of context and crime characteristics on sex offenders’ reaction to victim resistance. Crime & Delinquency, 58(4), 588–611. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128712437914.

Beauregard, E., Proulx, J., Rossmo, K., Leclerc, B., & Allaire, J.-F. (2007). Script analysis of the hunting process of serial sex offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34(8), 1069–1084. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854807300851.

Bishop, C. (2006). Pattern recognition and machine learning. Springer. Retrieved from http://www.amazon.ca/exec/obidos/redirect?tag=citeulike09-20&path=ASIN/0387310738.

Braga, A. A. (2005). Hot spots policing and crime prevention: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 1(3), 317–342.

Clarke, R. V. G. (1997). Situational crime prevention. Criminal Justice Press, Monsey, NY. Retrieved from http://www.popcenter.org/library/reading/pdfs/scp2_intro.pdf.

Clay-Warner, J. (2002). Avoiding rape: the effects of protective actions and situational factors on rape outcome. Violence and Victims, 17(6), 691–705. https://doi.org/10.1891/vivi.17.6.691.33723.

Cornish, D. B., & Clarke, R. V. (2014). The reasoning criminal: rational choice perspectives on offending. Transaction Publishers.

Costa, E. B., Fonseca, B., Santana, M. A., de Araújo, F. F., & Rego, J. (2017). Evaluating the effectiveness of educational data mining techniques for early prediction of students’ academic failure in introductory programming courses. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.047.

Felson, M., & Clarke, R. V. (1998). Opportunity makes the thief. Police Research Series, Paper, 98, 1–36.

Finkelhor, D., Asdigian, N., & Dziuba-Leatherman, J. (1995a). The effectiveness of victimization prevention instruction: an evaluation of children’s responses to actual threats and assaults. Child Abuse & Neglect, 19(2), 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(94)00112-8.

Finkelhor, D., Asdigian, N., & Dziuba-Leatherman, J. (1995b). Victimization prevention programs for children: a follow-up. American Journal of Public Health, 85(12), 1684–1689. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.85.12.1684.

Fisher, B. S., Daigle, L. E., Cullen, F. T., & Santana, S. A. (2007). Assessing the efficacy of the protective action–completion nexus for sexual victimizations. Violence and Victims, 22(1), 18–42. https://doi.org/10.1891/vv-v22i1a002.

Guerette, R. T., & Santana, S. A. (2010). Explaining victim self-protective behavior effects on crime incident outcomes: a test of opportunity theory. Crime & Delinquency, 56(2), 198–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128707311644.

Jordan, J. (2005). What would MacGyver do? The meaning(s) of resistance and survival. Violence Against Women, 11(4), 531–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801204273299.

Leclerc, B., & Wortley, R. (2015). Predictors of victim disclosure in child sexual abuse: additional evidence from a sample of incarcerated adult sex offenders. Child Abuse & Neglect, 43, 104–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.03.003.

Leclerc, B., Wortley, R., & Smallbone, S. (2010). An exploratory study of victim resistance in child sexual abuse: offender modus operandi and victim characteristics. Sexual Abuse, 22(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063209352093.

Leclerc, B., Wortley, R., & Smallbone, S. (2011a). Getting into the script of adult child sex offenders and mapping out situational prevention measures. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 48(2), 209–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427810391540.

Leclerc, B., Wortley, R., & Smallbone, S. (2011b). Victim resistance in child sexual abuse: a look into the efficacy of self-protection strategies based on the offender’s experience. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(9), 1868–1883. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260510372941.

Leclerc, B., Chiu, Y.-N., Cale, J., & Cook, A. (2016). Sexual violence against women through the lens of environmental criminology: toward the accumulation of evidence-based knowledge and crime prevention. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 22(4), 593–617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-015-9300-z.

Maeda, M. (2015). Detailed explanation of Japanese penal code (6th ed.). Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

Nurius, P. S., & Norris, J. (1996). A cognitive ecological model of women’s response to male sexual coercion in dating. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 8(1–2), 117–139. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v08n01_09.

Pang, B., Lee, L., & Vaithyanathan, S. (2002). Thumbs up?: sentiment classification using machine learning techniques. In Proceedings of the ACL-02 conference on Empirical methods in natural language processing—volume 10 (pp. 79–86). Association for Computational Linguistics. Retrieved from http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1118704.

Sarnquist, C., Omondi, B., Sinclair, J., Gitau, C., Paiva, L., Mulinge, M., Cornfield, D. N., & Maldonado, Y. (2014). Rape prevention through empowerment of adolescent girls. Pediatrics, 133(5), e1226–e1232. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-3414.

Senn, C. Y., Eliasziw, M., Barata, P. C., Thurston, W. E., Newby-Clark, I. R., Radtke, H. L., & Hobden, K. L. (2013). Sexual assault resistance education for university women: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial (SARE trial). BMC Women’s Health, 13, 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-13-25.

Senn, C. Y., Eliasziw, M., Barata, P. C., Thurston, W. E., Newby-Clark, I. R., Radtke, H. L., & Hobden, K. L. (2015). Efficacy of a sexual assault resistance program for university women. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(24), 2326–2335. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1411131.

Tark, J., & Kleck, G. (2014). Resisting rape: the effects of victim self-protection on rape completion and injury. Violence Against Women, 20(3), 270–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801214526050.

Tong, S., & Koller, D. (2001). Support vector machine active learning with applications to text classification. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 2(Nov), 45–66.

Ullman, S. E. (1998). Does offender violence escalate when rape victims fight back? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 13(2), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626098013002001.

Ullman, S. E. (2007). A 10-year update of “review and critique of empirical studies of rape avoidance”. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34(3), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854806297117.

Ullman, S. E., & Knight, R. A. (1992). Fighting back: women’s resistance to rape. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 7(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626092007001003.

Yamashita, T., & Yamaguchi, A. (2016). Statute Books (Heise 28). Yubikaku. Retrieved from http://www.yuhikaku.co.jp/six_laws/detail/9784641104761.

Zaleski, K. L., Gundersen, K. K., Baes, J., Estupinian, E., & Vergara, A. (2016). Exploring rape culture in social media forums. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 922–927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.036.

Zoucha-Jensen, J. M., & Coyne, A. (1993). The effects of resistance strategies on rape. American Journal of Public Health, 83(11), 1633–1634. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.83.11.1633.

Funding

The present study was funded by a grant from the Foundation for the Fusion of Science and Technologies (Heisei27-10).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in the present study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

The present study abbreviated informed consent for three reasons. First, the participants’ informed consent and researchers’ will do not affect our sampling methods, because our criminal suit documents are based on daily activity logs in Japanese courts. Regardless of the participants and researchers’ will, Japanese courts created and stored the documents as their professional tasks. Second, if we analyzed only those who could provide informed consent in prison, the data could be strongly biased and would not be representative of sexual offenders in the Japanese prison. Third, an analysis of criminal documents is the best method to clarify effective behavioral sequences for avoiding rape. The effective behavioral sequences for avoiding rape were essential to prevent sexual victimization.

Given these reasons, we abbreviated informed consent. Abbreviation of informed consent is frequent in epidemiological study (e.g., information about influenza and the Ebola virus was frequently used without informed consent from patients). The present study was also acknowledged by an ethical committee in a local university and a research committee in a local prison in Japan.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yokotani, K. Supervised Machine Learning Approach Discovers Protective Sequence for Avoiding Sexual Victimization in Criminal Suit Documents. Asian J Criminol 13, 329–346 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-018-9273-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-018-9273-1